Blank Books & Papers for Writing Workshop

These blank books include an assortment of free books and lined papers for your writing workshop.

This is another free resource for teachers from The Curriculum Corner.

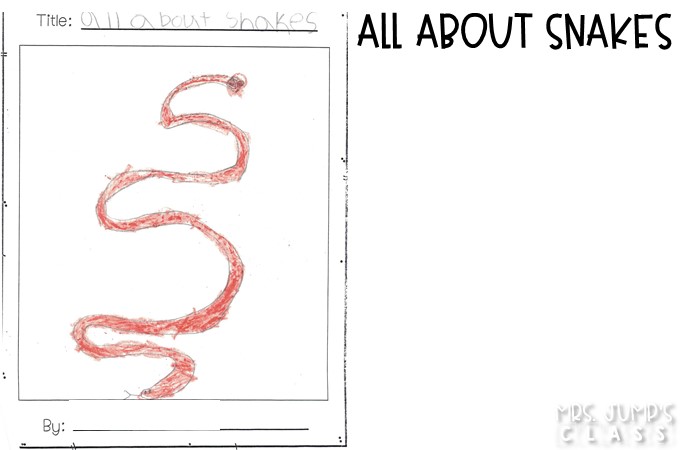

We have put together a new collection of blank books and papers for your writing workshop.

Why we Like Blank Books for Writing

We use blank books for our own students because it is familiar to them. When they read, they read books, not a single page filled with text.

Using blank books helps them feel like authors which in turn, makes them produce writing they are proud of! Of course, there will still be times when students use lined pages, but on a day-to-day basis, we use blank books more often.

Getting these Booklets Ready

For the books, we have included different cover and page choices within each file.

You can download and print the file once and have multiple pages to choose from. This will make creating the perfect book for each student easier. Or, lay out the paper choices and allow your students to choose the ones that they like best!

Blank books are a part of our writing workshop.

We teach our students how to use them during our launching unit for writing workshop.

If you need help getting your writing workshop started, you might want to take a look at our launching unit of study. Writing Launching Unit

You can download our collections of blank books below:

- Horizontal Books

- Vertical Books

- Horizontal Pages

- Vertical Pages

- Half Fold Books

Many teachers also offer comic book style pages as an option. If you would like to try allowing your authors to write comic strips, you will find them here: Comic Book Templates

You might also like our set for writing informational text: Nonfiction Books

Do you have great ideas for how to use these books? Share below to help other teachers. Even better, send us a photo of a student’s finished writing. We love to see how our resources are used in the classroom.

As with all of our resources, The Curriculum Corner creates these for free classroom use. Our products may not be sold. You may print and copy for your personal classroom use. These are also great for home school families!

You may not modify and resell in any form. Please let us know if you have any questions.

Author Study: Meet Seymour Simon - The Curriculum Corner 4-5-6

Monday 6th of April 2020

[…] Blank Books […]

Kindergarten Sub Plans - Set 2 - The Kinder Corner

Tuesday 4th of February 2020

[…] Here is a link to some various blank books and lined paper in case you have something different and more open-ended in mind. It never hurts to have a stack of lined paper ready for a time-filler writing activity in your room! Blank Books & Papers […]

5th Grade Sub Plans - Set 2 - The Curriculum Corner 4-5-6

[…] Blank Books are a good addition to your sub tub. Provide an assortment of blank books and lined pages. […]

4th Grade Sub Plans - Set 2 - The Curriculum Corner 4-5-6

1st Grade Sub Plans - Set 2 - The Curriculum Corner 123

Monday 3rd of February 2020

[…] Blank Books are a good addition to your sub tub. Provide an assortment of blank books and lined pages. […]

- HOW TO GET STUDENTS WRITING IN 5 MINUTES OR LESS

Writer’s Workshop Middle School: The Ultimate Guide

Feb 23, 2021

Writer’s Workshop Middle School: The Ultimate Guide defines the writer’s workshop model, its essential components, pros and cons, step-by-step set-up, and further resources.

What is the writer’s workshop model?

Writer’s workshop is a method of teaching writing developed by Donald Graves and Donald Murray , amongst other teacher-researchers.

The writer’s workshop provides a student-centered environment where students are given time, choice, and voice in their learning. The teacher nurtures the class by creating and mentoring a community of writers.

So, why does the writer’s workshop in middle school matter?

Students learn more during the writer’s workshop because you can mentor them toward what they need to know and practice, and they have lots of time to write and read in order to improve at their own pace (to an extent).

For example, if the skill I need to teach is how authors use mood and tone to create meaning , then I would use a mentor text to teach that concept. However, after reading, the focus will not be on answering questions about the text in written form. Instead, I demonstrate how writers choose particular words and the arrangement of those words to create a mood and tone.

Students then try creating mood and tone with their own pieces of writing. Only after students have practiced their own creations, do I then circle back around to other literature for students to practice literary analysis of mood and tone and its effect on meaning.

Why I focus on writing in the ELA classroom?

I’ve found students are more likely to read assigned texts if I’ve given them a reason to use those texts. That reason? To apply what they learn from mentor texts to their choice writing. Middle school students love to express themselves in creative ways, and by giving students this choice, you build engagement and motivation to continue learning.

The essential components of the writer’s workshop in middle school are:

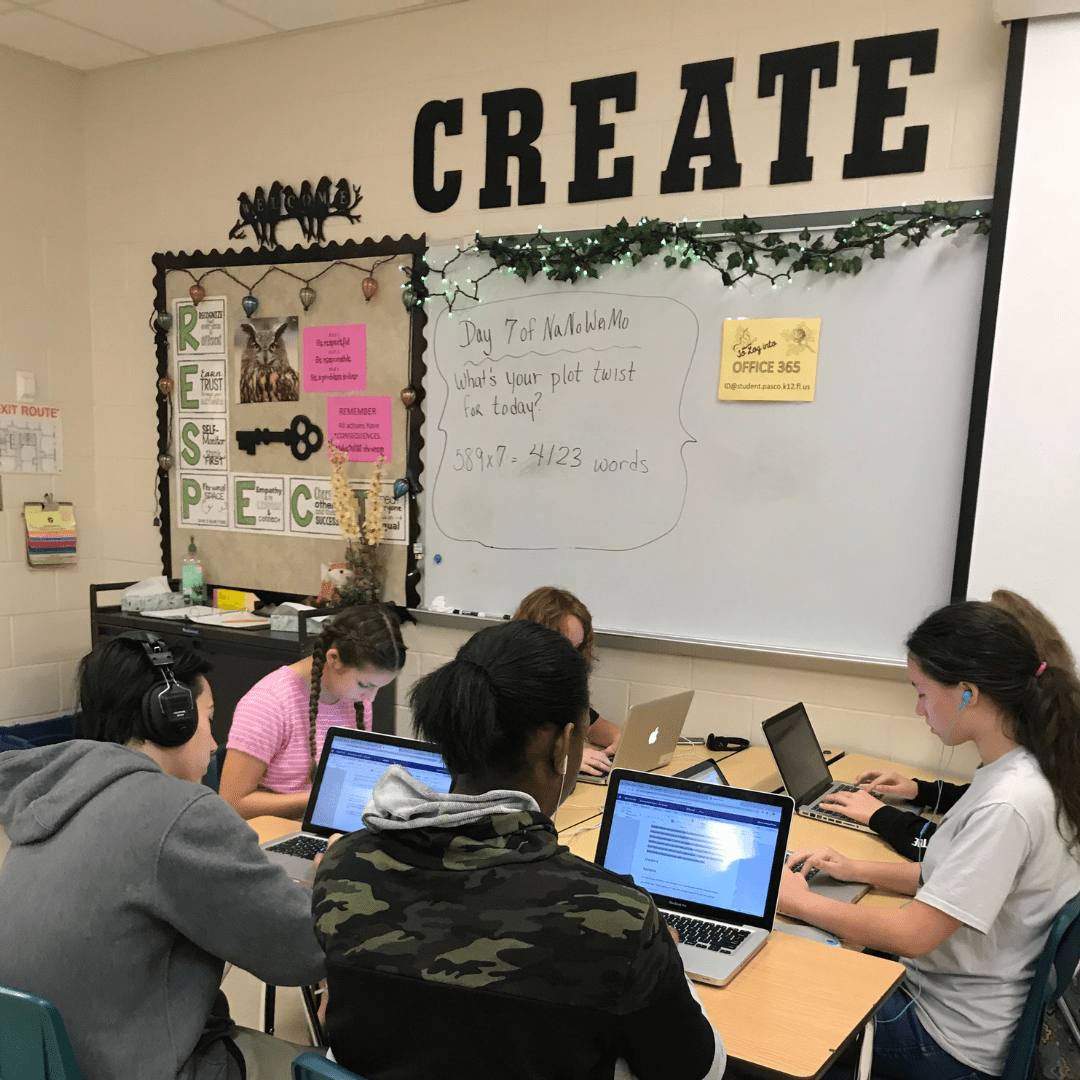

- Time to write daily

- Student choice

- Exploring the writer’s voice

- Building a community of writers

- Mentor teaching

1. Time to Write Daily

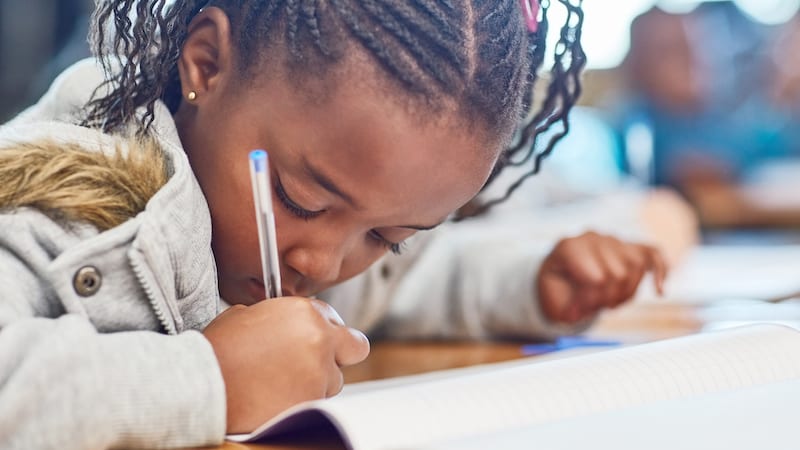

Students need a chance to write daily. Various ways you can do this are through Bell Ringers at the beginning of the class, writing during the mini-lesson, and writing projects during workshop time. My students use writing journals because they need a space to think before they face a blank computer screen.

Students do read in my classes. However, their purpose for reading is to become better writers. This reading is either assigned, student choice, or a choice between the assigned reading and student choice, depending on the skill or concept I’m targeting that week.

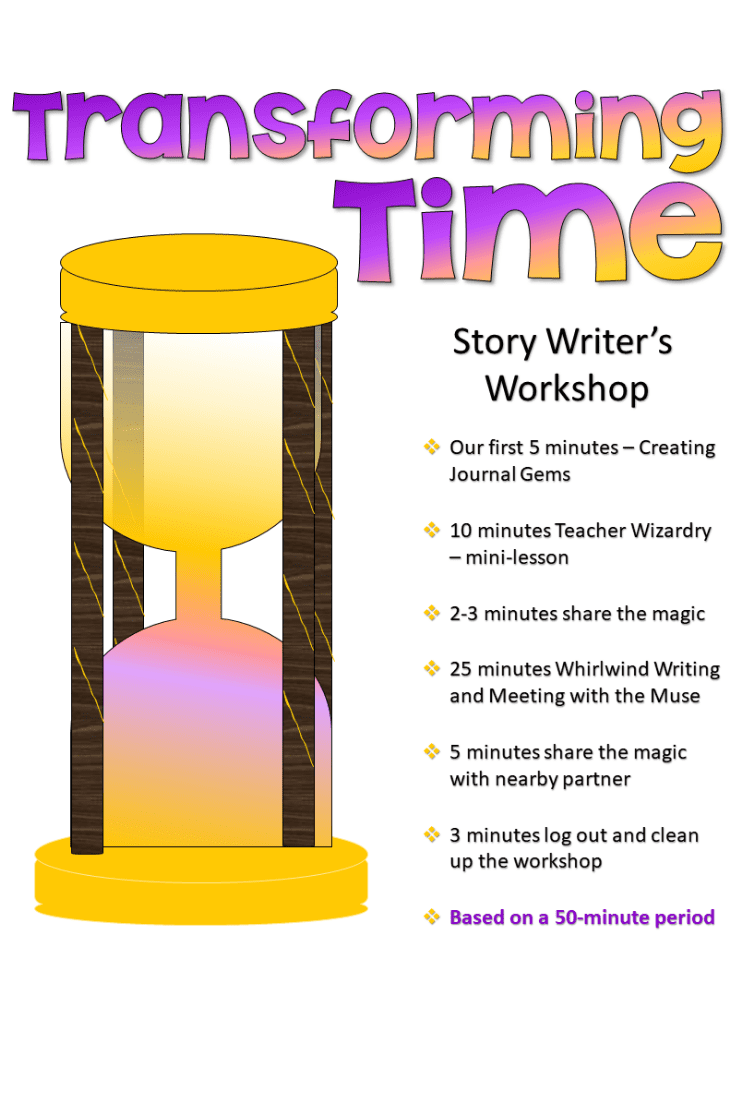

This is how I break up our daily writing:

- Write Now (bell ringer)

- Mini-lesson and sharing

- Writing/Reading Workshop while I confer with writers

- Short turn and talk, log off computers and pack up

Below is an example of my story writer’s workshop time transformation. This is what I use when we are writing narratives. I’m using a fantasy magic theme here:

2. Student Choice

To keep students motivated to write, you want to build in student choice whenever and wherever possible. Just to clarify, you don’t have to give them choices for everything they do.

For one thing, that would be as overwhelming as shopping on the cereal aisle at your local grocery store. Just too many choices.

When I introduce a concept, I may give them a few choices on how students can practice that concept. If I give them a writing assignment, I often allow them ONE choice in topic, genre, audience, or mode of writing.

If you need students to complete an assignment/activity within a certain time period, tell them ahead of time. Let them know they can turn in an excerpt if they want to write something longer than you expect.

Of course, this is not always possible. They need to learn how to write within certain time parameters. So, let them practice this through timed writings or word sprints .

One way to help students with choice is to have them do listing activities frequently. They could even have a section in their writing notebooks just for lists of ideas.

3. Exploring the writer’s voice

Writer’s voice – that elusive term that most writers have no idea how to achieve until they’ve written for a while, and then finally realize they have it. The ultimate goal for me as a writing teacher is to help my students to find their voice.

I want students to be able to explore what is important to them personally and to explore how they can share this with others. From encouraging students to participate in small group sharing to author’s celebrations, students need the opportunity to see their writing voice matters.

There are so many different ways for kids to publish safely online – Edublogs, Adobe Spark, Google Sites, FlipGrid, etc.

4. Building a community of writers in your writer’s workshop for middle school

Middle school students are very social, but even the quiet writers need to socialize often with other writers. This component of the writer’s workshop for middle school is what makes this model an actual workshop.

Students share their writing with each other. Usually, I allow for natural partnerships and groups to form. However, at the beginning of the year, I often pair up students for short activities. This helps everyone feel more comfortable with each other.

One way I build a community of writers is to play the name game at the beginning of the year. We all stand in a circle and we toss a ball to each other and say our name and all the people who have had the ball tossed to them. It gets fun when students start to forget names. They all start out being self-conscious but end up laughing and smiling.

Another way to build a community is during share time. I have students write in their notebooks as soon as they come into the classroom as a warm-up, starter activity that I call Write Nows. These Write Nows are projected up on the screen, and students write for 2-5 minutes. After this, I ask students to turn and talk to a neighbor about what they wrote.

Sometimes this writing is a review of the previous day or another activity that goes along with the skill we are learning. Other times it is a prewriting activity that helps break writer’s block .

Write a Letter to your Students

To help students get to know me as a community member, I write a letter to them and they write back to me. This starts the relationship-building between my students and me within the first week, and I conference with the students about their letters. This also gets them into the swing of a writer’s workshop.

My students love this letter-writing activity that I’ve done every year for the past 24 years. It’s a hit every year and establishes the tone and mood of our workshop.

5. Teacher as Writing Mentor

One of the most important components of the writer’s workshop in middle school is you – the writing teacher.

To teach writing well, you should write along with your students. Over the years, I’ve written on transparencies, used a document camera, and filmed myself writing. All of these methods work. Generally, I write along with students during the bell-ringer activity, which I call Write Now, but sometimes I’ve prewritten the Write Now.

Additionally, I show students my various writing projects, both published and unpublished, during daily lessons.

My students have seen this blog, heard my podcasts , listened to me read aloud from stories I’ve written and/or published. My students are the ones who pushed me to publish my first YA books . You’ll be amazed at what you come up with and how this creates a bond with your students that lasts a lifetime.

Also, by completing the writing assignments you assign, you’ll be able to empathize with and anticipate the writer’s struggle with each assignment.

Terms to Know for Writing Workshop

This is not an exhaustive list, but one that will be added to as I find more terms that should be added here.

Activity: the practice of a skill or process, especially when gaining new knowledge

Assignment: a product created by the student after practicing a skill or process that may be revised up until a particular due date

Bell ringer: a beginning of the period activity (I call these Write Nows in my class)

Blended learning environment: in-person LIVE teaching and learning or digital learning with recorded lessons

Conference: a meeting between teacher and student about their writing

Journal write: handwriting in a journal for ideas, bell ringers, collecting information, etc.

Mini-lesson: a short 5-10 minute lesson that teaches either a whole or partial skill or process

Mastery Learning: quizzing students on their conceptual knowledge, giving them different activities based on the results of their quizzes – either reteach or extend – and quizzing again. Revisions can also be mastery-learning pieces.

Mentor texts: well-written, multicultural texts used to demonstrate a literary concept or style

Rubric: a breakdown of the skill into levels of learning – students revise to earn a higher level

Writing Workshop Middle School Pros and Cons

- Builds student relationships with you and each other – lots of SEL

- Easier to differentiate for students than the traditional classroom model

- Grading can be accomplished during conferences

- Students are more engaged and begin to enjoy writing

- They might even enjoy reading more, too

- Mini-lessons are short, sweet and to the point, less prep time for presentations

- Breaking through writer’s block

- Teaching students how to use the technology

- Helping students revise if they don’t have access to technology

- Adapting to technology challenges that arise (switch to writing journals or change Internet browsers)

- Deadlines can be difficult to manage sometimes

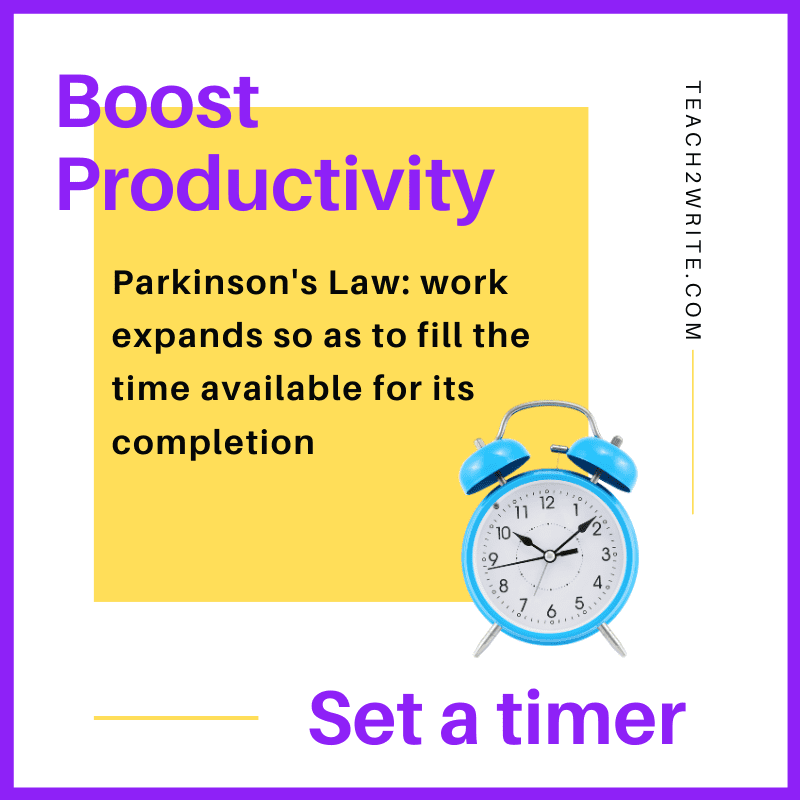

As far as time management is concerned – one of the things I am going to stress to my students is the need for getting assignments turned in, even if it’s not perfect. I need to be able to keep them to deadlines. So, this year, I’m going to teach my student’s Parkinson’s Law :

How to start a writer’s workshop for middle school

These are the steps I’m taking this year to start my writer’s workshop, and I’ve used these for quite a few years now. Some steps may be done simultaneously on the same day. There will be future blog posts about each of these steps.

- Create a welcoming classroom space.

- Decide what technology you will be using – hardware and software. If you need help with Canvas LMS, click here .

- Send out your course syllabus with materials students will need for your course.

- Create a course outline based on your school’s curriculum guides or state standards.

- Plan and post your first 2 weeks of lessons and assignments into your online course (if you are using technology in your course).

- Establish classroom expectations and routines.

- Build a classroom community of writers.

- Show students how to navigate your course online.

- Write a letter to your students and have them write back to you as their first assignment.

- Confer with your writers as they are writing their letters and make a list for yourself of things students need to work on with their writing.

- Set up writing journals and begin writing workshop routines.

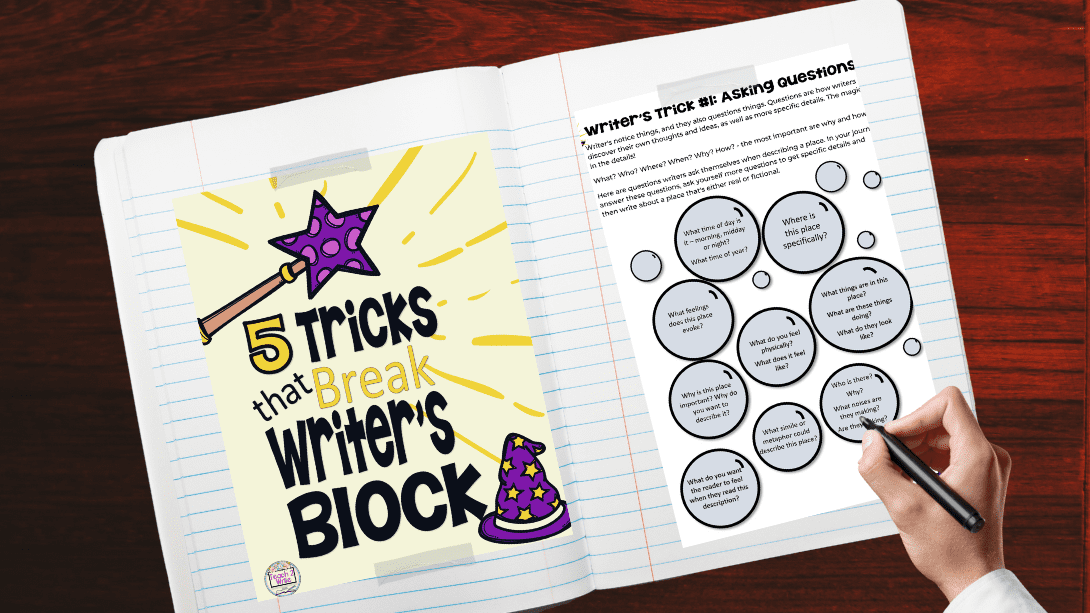

- During mini-lessons, teach the 5 tricks that break writer’s block .

- Students write in journals to gather ideas and begin writing pieces.

- Assign a short writing piece and confer with writers during workshop time.

- Teach ONE revision strategy during a mini-lesson, depending on your curriculum.

- Teach ONE editing strategy during a mini-lesson, depending on your curriculum.

- Allow writers to revise and edit before turning in their first short writing assignment.

- Celebrate your writers with the Author’s Chair presentations.

- Continue writer’s workshop by using daily bell ringers, mini-lessons about writing and reading, sharing, writing/reading workshop, conferencing, and turn and talk.

- Breakaway from the writer’s workshop routine every once in a while to play – escape rooms, read-arounds, watch a movie, celebrate authors, group brainstorm, catching up on overdue assignments.

References for Writing Workshop in Middle School

Atwell, Nancie. In the Middle: A Lifetime of Learning about Writing, Reading, and Adolescence. Heinemann, 2014.

Graves, Donald H. “All Children Can Write.” http://www.ldonline.org/article/6204/

Lane, Barry. After The End: Teaching and Learning Creative Revision. Heinemann, 2015.

Murray, Donald. “The Listening Eye: Reflections on the Writing Conference” https://secure.ncte.org/library/NCTEFiles/Resources/Journals/CE/1979/0411-sep1979/CE0411Listening.pdf

Learning materials for Writing Workshop for Middle School

Writing Literary & Informative Analysis Paragraphs

Students struggle with writing a literary analysis , especially in middle school as the text grows more rigorous, and the standards become more demanding. This resource is to help you scaffold your students through the process of writing literary analysis paragraphs for CCSS ELA-Literacy RL.6.1-10 for Reading Literature and RI.6.1-10 Reading Information. These paragraphs can be later grouped together into writing analytical essays.

PEEL, RACE, ACE, and all the other strategies did not work for all of my students all of the time, so that’s why I created these standards-based resources.

These standards-based writing activities for all Common Core Reading Literature and Informational standards help scaffold students through practice and repetition since these activities can be used over and over again with ANY literary reading materials.

Included in these resources:

- step-by-step lesson plans

- poster for literary skills taught in this resource

- rubrics for assessments standards-based

- vocabulary activities and notes standard-based

- graphic organizers that incorporate analysis of the literature and information standard-based

- paragraph frames for students who need extra scaffolding standard-based

- sentence stems to get students started sentence-by-sentence until they master how to write for each standard

- digital version that is Google SlidesTM compatible with all student worksheets

List Making: This resource helps students make 27 different lists of topics they could write about.

Sensory Details: This resource will help you to teach your students to SHOW, not tell. Descriptive writing with a sensory details flipbook and engaging activities that will get your students thinking creatively and writing with style.

Included in this resource are 2 digital files:

- Lesson Plans PDF that includes step-by-step lesson plans, a grading rubric to make grading faster and easier, along with suggestions for what to do after mind mapping.

- Google SlidesTM version of the Student Digital Writer’s Notebook allows students endless amounts of writing simply by duplicating a slide.

Recent Posts

- Text Features Vs Text Structures: How to introduce text structures to your students

- Nurture a Growth Mindset in Your Classroom

- 3 Middle School Writing Workshop Must-Haves

- Writing Strategies for Middle School Students

- Writing Response Paragraphs for Literature

- September 2023

- October 2022

- August 2022

- January 2022

- October 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- September 2019

- February 2019

- October 2018

- February 2018

- Creative Writing

- middle school writing teachers

- Parent Help for Middle School Writers

- writing strategies and techniques for writers

- Entries feed

- Comments feed

- WordPress.org

Privacy Overview

- Grades 6-12

- School Leaders

Creative Ways to Use Graphic Novels in the Classroom! 🎥

What Is Writing Workshop?

An essential part of the responsive classroom.

If you’re new to teaching writing, you may have heard discussion about writing workshop but not be entirely sure about what it is or how to use it in your classroom. WeAreTeachers is here with the answer.

What is writing workshop?

Writing workshop is a student-centered framework for teaching writing that is based on the idea that students learn to write best when they write frequently, for extended periods of time, on topics of their own choosing.

To develop skills as a writer, students need three things: ownership of their own writing, guidance from an experienced writer, and support from a community of fellow learners. The writing workshop framework meets these needs and streamlines instruction in order to meet the most important objective: giving kids time to write. The workshop setting supports children in taking their writing seriously and viewing themselves as writers.

The four main components of writing workshop are the mini-lesson, status of the class, writing/conferring time, and sharing. There is not a prescribed time limit for each component, rather they are meant to be flexible and determined by students’ needs on any given day.

1. Mini-lesson (5 – 15 minutes)

This is the teacher-directed portion of writing workshop. Mini-lessons should be assessment-based, explicit instruction. They should be brief and focused on a single, narrowly defined topic that all writers can implement regardless of skill level. According to writing guru Lucy Calkins , mini-lessons are a time to “gather the whole class in the meeting area to raise a concern, explore an issue, model a technique, or reinforce a strategy.”

Sources for mini-lessons can come from many places. Many teachers follow the scope and sequence of a prepared curriculum or use the state or national standards as a guide. Ideally, topics for mini-lessons come from your observations as you conference with your students and become aware of their needs.

The four parts of a mini-lesson:

- Connection (activating students’ prior knowledge)

- Teaching (presentation of the actual skill or topic)

- Active engagement (giving students time for supported practice of the skill)

- Link (helping students figure out how the topic pertains to their individual writing piece).

For a helpful description of the mini-lesson process, read Writing Workshop Fundamentals by Two Writing Teachers.

2. Status update (3 – 5 minutes)

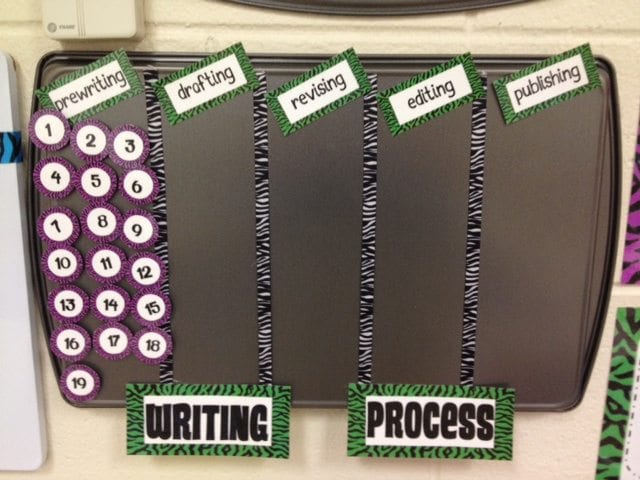

Meant to be a quick check-in, status update is a way to find out where your students are in the writing process— pre-writing, drafting, revising, editing, evaluating, or publishing.

Status of the class doesn’t have to happen every day and it needn’t take up much class time. It can be a quick verbal check-in or “whip” around the classroom. Or you may want to use a clip chart, notebook, or a magnet chart.

SOURCE: Polka Dots and Pencils

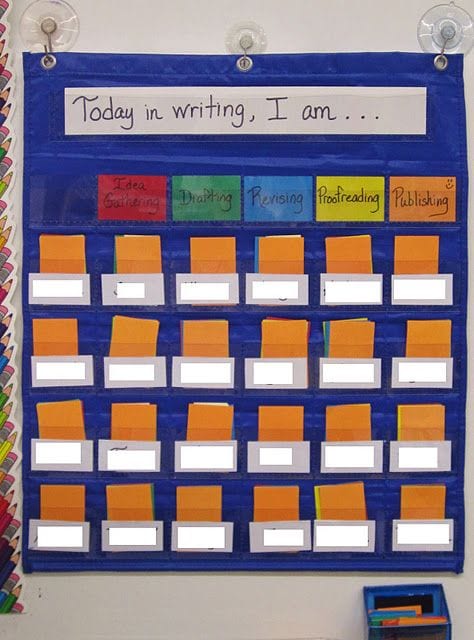

Another great idea is to use a pocket chart. Students show which step they are on by putting the appropriately colored card in their pocket.

SOURCE: Teaching My Friends

Status update lets you as the teacher evaluate how your students are progressing. It also creates accountability for the students and motivates your community of learners.

3. Writing (20 – 45 minutes)

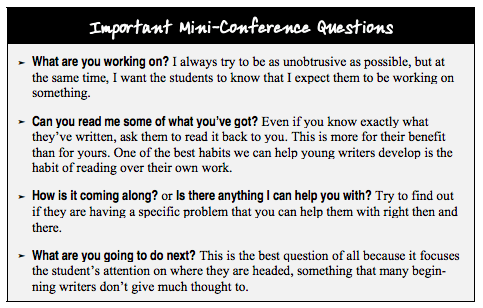

The majority of writing workshop is devoted to simply giving students time to write. During this time, teachers can either be modeling the process by working on their own writing or conferencing with individual students. In all reality, the majority of your time will be observing and helping students. A good goal during a typical week of writing workshop is to aim to work individually with every student in the class at least once.

Remember, the main priority of conferencing is to listen, not to talk. But to prompt your students to share their progress with you, here are a few questions to ask from Teaching That Makes Sense .

Once your students get the hang of what a helpful conference looks and feels like, they can use peer conferencing to help one another.

4. Sharing (5–15 minutes)

It can be tempting, when time is running short, to skip this last element of writing workshop, but don’t! It can be the most instructionally valuable part of the class, other than the writing time itself. When students grow comfortable seeing themselves as part of a writing community, they are willing to take more risks and dive deeper into the process. In addition, kids often get their best ideas and are most influenced by one another.

Some tips to keep sharing time manageable:

- For whole-class sharing, keep a running list of who has shared and when, and h ave students share only a portion of their writing—maybe what they consider their best work, or a part they need help with.

- Let students share in pairs—one reads aloud and one listens.

- Have students swap work and read silently to themselves.

At first the concept of writing workshop may seem overwhelming. But once you establish your routine, you’ll be surprised how easy it is to implement. Because writing workshop gives students so much time to write, their writing skills will improve dramatically. And hopefully, being part of such a dynamic writing community will instill in your students a lifelong love for writing.

Got any hot tips for using writing workshop in your classroom? We’d love to hear about them in our WeAreTeachers HELPLINE group on Facebook.

Plus, check out 5 Peer Conferencing Strategies that Actually Work .

You Might Also Like

What Teachers Need to Know About Dysgraphia

This goes way beyond messy handwriting. Continue Reading

Copyright © 2024. All rights reserved. 5335 Gate Parkway, Jacksonville, FL 32256

Princeton Writing Program

The Writing Workshop and Its Variations

The draft workshop is the fundamental, flexible tool for teaching writing. It can also be one of the most fun. On the surface, it is simply a facilitated conversation among students about a draft produced by one of their classmates with the aim of producing a revision strategy. But it is also a construction site for a classroom community embodying an ethos of honest, generous feedback, and a training field for students to become stronger critical readers and writers. As instructors, the draft workshop is where we most try to render ourselves obsolete, over time slowly handing over responsibility for substantive feedback to the class as the students develop the intellectual muscles to handle it. The draft workshop does not necessarily require an eye on the long game: it can be dropped into a class nearly anytime, for any reason, to good effect, so long as you have writing in need of revision and students ready to talk about it. Here is the full forty-minute classic edition of the draft workshop, followed by fifteen of its infinite variations.

The Draft Workshop

Prep Work: Select a student draft for the workshop and distribute it to your class with reasonable lead time. There are many approaches to determining which draft will be workshopped in a given class: ask for a volunteer, designate a student in advance of the deadline, or quickly skim the submitted papers ahead of class to select a draft that has usefully representative strengths and weaknesses. Ask students (save the writer) to read the draft closely and compose a response letter addressed to the author with four components:

- A quick summary of what they see as the draft’s motive and thesis.

- A specific reflection, with evidence from the text, on one important strength of the draft (often with reference to a high-order Lexicon element, e.g., thesis, motive, analysis, structure).

- A specific reflection, with evidence from the text, on one important weakness of the draft.

- Specific ideas for how to address the weakness identified in #3 through revision.

The letter should be about a page long and students should bring two hard copies to class on the day of the workshop, along with the draft itself. At the end of class, one copy of the letter goes to the author and the other to you. Be sure to closely read the draft yourself to develop your own sense of its strengths and weaknesses.

Step One: (2 minutes) Open the workshop by asking the writer to briefly—emphasis on briefly—share what he or she is attempting to argue in the draft and then identify one or two hopes for revision and for the discussion to follow.

Step Two: (10 minutes) Open the floor by asking students to identify strengths of the draft and to record their findings on the board. Contributions must be specific; encourage students to “show us in the text.” They should also identify the precise way(s) the identified strength improves the essay (making the thesis more persuasive, introducing complicated evidence in a clear way, deftly addressing a counterargument, and so on). Try to spend at least a quarter of the time you allot to the workshop here, and resist student attempts to pivot to weaknesses.

Step Three: (25 minutes) Once a critical mass of strengths is on the table, move on to areas in need of revision, or what Richard Martin so aptly calls “strengths-in-the-making.” Students should again show evidence from the text itself and explain why, in their view, the specific weakness they identify problematically affects the entire essay. As you record these findings, encourage students to suggest revision strategies to address the concerns, ideally fielding multiple possible approaches for each issue (these will often be mutually exclusive, and that’s fine). The majority of your workshop time will be spent here.

Step Four: (3 minutes) Before the workshop wraps up, pause to consider what has been said and what your copious notes on the board may suggest for next steps. Take a few minutes to talk through what the most important priorities for revision should be. The writer will not be able to address everything, and there will often be competing strategies for revision. Highlight the three or four most important things for the writer to focus on. Do not skip this step; be sure to leave yourself enough time. Close by thanking the writer for sharing their work, and the rest of the class for their considered feedback.

Some Advice for Running the Draft Workshop

As simple as the steps above may be, the draft workshop is actually quite challenging to teach well, particularly early in the semester when students are still getting acclimated to the class and to each other. In time, as a product of early investment on your part, the draft workshop eventually runs itself. But you have to get it there. Below, we revisit each of the four steps to provide some advice we hope proves useful, whether you plan to use the workshop model just once or to make it a recurring feature of your course.

At Step One: Early in the semester, or in your class’s first workshop, the position of being on the “hot seat” can be uncomfortable. Even students who appear relaxed or non-defensive can get unnerved the moment they realize their work is about to go under the microscope. This discomfort typically manifests as a desire to simply keep talking when you hand them the floor at the beginning of the workshop, either by preemptively defending themselves from every attack they can think of, or by proclaiming their draft worthless and apologizing for wasting everyone’s time. In either case, kindly but firmly cut off the monologue and trust that Step Two will help mitigate the fear.

We don’t recommend making any general rules that limit the author’s ability to speak. You will occasionally need to manage an over-talker, but the risks of telling authors to stay silent while their work is discussed are substantially greater. They miss out on the opportunity to clarify their thinking in dialogue with their readers, and even the thickest-skinned among them may end the workshop feeling exposed and disempowered. A draft workshop should be a rigorous and challenging discussion with the author as full participant, not a passive—or aghast—spectator. Another important way to respectfully involve the author is to have students address all their comments and questions about the draft explicitly to the writer. For example, “I thought the paragraph at the bottom of page two was awesome because you really show me there the problem your essay is trying to solve.” Or: “I was wondering if you could say more about the point you bring up on page five? It seems like x evidence from the book might contradict that?”

Students will be tempted to start referring to the writer in the third person and addressing their comments to you, the instructor, since you’re the one standing at the board and facilitating the conversation. Redirecting students to engage directly with the author, and reframing their contributions only if necessary, is a crucial part of your job.

At Step Two: Some students are inclined to view this step as an inefficient “buttering up” of the author before the real work of devastating criticism begins. That’s the case only if it’s done badly. The opening step of appreciation should be just as rigorous, efficient, and real as the work of rigorous, efficient, and compassionate criticism that follows. It’s important for the author to see genuine accomplishments in a draft, not only to encourage confidence for the revision ahead, but also to hedge against reverse revision. If we don’t explicitly identify the strengths and show the author in the text where and how their draft is working well, it’s liable to disappear in the course of revision when addressing the weaknesses to be discussed in Step Three. Moreover, it is often news to the author that the strengths are in fact strong. Novice writers, or even experienced writers lost in the weeds, sometimes need an outsider to point out what is particularly successful.

Even seasoned workshoppers may get impatient with this step. For instance, to force a segue to the paper’s weaknesses their contribution may begin with the construction, “I really like x, but…” A more welcome version of this move is, “I really like x, and you could make it even better by…” (which you should feel free to pursue in detail). While you don’t need to identify every last thing a draft does well, or hold the conversation here longer than is productive, be sure to resist moves that prematurely highlight weaknesses, making that transition only when you’re ready.

You may sometimes find it nerve-wracking to hear students offer praise for an aspect of the draft that actually still needs a lot of work—perhaps especially, “I think you have a really good thesis.” Resist the temptation to leap in immediately and contradict. Instead, that’s precisely the moment to ask the student who is commenting to point to where they see the thesis coming through most clearly in the text of the draft. Keep taking notes on the board. And be patient. In most cases the early praise for the thesis will be balanced out and usefully complicated as soon as Step Three comes around (or even sooner). In the rare cases where students don’t circle around to bring up questions or critiques of the thesis on their own, it’s important to prompt them before the workshop ends. If Rule #1 is Don’t freak out/Let them figure it out , then Rule #2 is Don’t leave them in the dark at the end .

At Step Three: The key to this step is linking the identification of a weakness to a revision strategy. This rule forces students to think constructively and take responsibility for considering how they themselves might respond to problems they uncover. It’s the difference between an exercise in evaluation versus an exercise in collaboration. It’s also a built-in trap for classroom alpha dogs: they’re welcome to propose sophisticated criticism, but then they also need to accept the work of helping their classmate find an escape hatch.

The structure of the conversation nudges the substance of contributions toward generosity, but by itself does nothing to guarantee a professional tone. Tone can be difficult for students to calibrate early, either because they don’t know how or because they don’t want to. An ethos of compassionate, honest criticism is not a mode that all students will naturally inhabit, and you will need to do the work of modeling it for them. One useful approach is to encourage students to frame concerns as a function of their experience as a reader, which keeps the focus on the text and not the writer. The difference between “I become confused at the top of page three when the draft moves to_____” and “You’re confusing at the top of page three when you_____” may seem minor, but the shift from “you” to “I” or “the draft” can make a world of difference in how willingly writers can hear and respond to feedback.

Be prepared to intercept frustrated, mocking, or otherwise insensitive criticism immediately and reframe it the way you want it to be heard. Normally, the simple act of publicly translating a student’s contribution is enough to make the tonal point clear. But be ready to intervene more directly if necessary, especially if the criticism is about the author rather than the draft. While uncomfortable for everyone, doing so protects the writer, preserves the values of the course and the workshop, and demonstrates to the rest of the class that they can trust you to protect them when it’s their turn to share their work. While you might find yourself performing acts of “translation” quite frequently, especially early in a semester, the need for more direct intervention is usually rare. Just as the quality of student feedback improves over time, so does the tenor of their contributions and their willingness to police each other’s tone.

At the other end of the spectrum, some students are so worried about hurting their peers’ feelings or appearing confrontational that they simply refuse to provide honest criticism at all. These students will clam up during Step Three and, if forced to make contributions, will offer vague generalities that dodge the real issues. It can help to ask students to share what they wrote in their response letter. Usually, when they discover they haven’t made an enemy of the author, this concern goes away.

You’ll want to use a lighter hand jumping into the substance of critical suggestions, but you should still do so when you find a contribution to be completely off base. Most of the time, you can invite further dialogue about the point and other students will build the case against it for you. Other times, it’s wise to make a polite show of skepticism while leaving it up to the author to decide what to do.

At Step Four: By now the author has received a barrage of feedback, and whether or not they’ve taken careful notes, whatever revision plan may exist in their head will be forgotten by their next class unless you take a moment to highlight the most important priorities the class has identified for revision. This step allows the author to register the major takeaways, and even if they aren’t yet sure how they will address these priorities, at least they will have a clear sense of where they should focus. It’s usually the case that a rough consensus emerges on what the revision priorities should be, even if there’s some disagreement about which priority is the most important. You should feel free to tilt the scales toward what you see as the best use of the writer’s time.

Variations on Draft a Workshop

Thought-lines: Prior to the workshop, divide students into twos and assign each pair a paragraph in the draft to summarize in a single sentence. Put these sentences on the board and then lead a discussion regarding the paper’s line of argument, or “thought-line.”

Thesis spot-checks: Invite students to rewrite from memory the thesis of the paper being workshopped. Before discussing, ask each student to read their version of the thesis to the class. Break the class into groups of three or four and have each group refine or complicate the paper’s thesis. Regroup and compare definitions, testing them against what the writer thought their thesis was.

Evidence/analysis check: Have students use one color of highlighter to identify evidence in the draft and another color to identify analysis. Then ask them to compare the overall proportion of each color in the paper (to ensure that evidence does not outweigh analysis) as well as where the colors appear (to check for integration of analysis with evidence).

Workshop smaller elements: Workshop titles, abstracts, openers, figures, and tables for all papers in the class. Circulate the papers themselves prior to the workshop or prepare dedicated handouts for the smaller items—all the titles in one document, all the abstracts in another. Then workshop your way through the “little” or “last-minute” pieces that are often overlooked in a draft but still carry great weight.

Writer-run workshop: Have students run their own draft workshops, following these two rules: 1) the writer begins by asking what the class finds promising or exciting about the draft (to ensure that the conversation begins with a focus on what’s working); and 2) the writer asks only questions unless they are responding to a question posed by one of their readers (to ensure that the author maintains a guiding voice in the discussion without overtaking it.

Student moderator: For the later workshops when the class has become skilled at workshopping, choose a student moderator to lead the workshop. Resist the urge to jump in. Let them know they’re in charge.

Small-scale peer response guides: Assign students to groups of two or three and, for homework, have each group circulate and read all drafts from their group and write response letters ahead of time. In class, convene the groups and provide them with a “response guide” handout of questions to discuss about each draft, encouraging them to draw on their response letters during their conversation. (Tip: focus the handout on issues common to all papers.)

Advisory councils: As the workshop begins, break students into three advisory councils, each charged with a different Lexicon element. For example, the first might focus on thesis, the second on source use, and the third on structure. Allow time for these councils briefly to convene, both to review the Lexicon element(s) and to read the paper under discussion (if they haven’t read it before class). Reconvene the councils when they are ready to offer the draft writer advice.

Highlight general applicability: Have all students in class bring copies of their drafts to the day’s workshop. At appropriate moments during the class as a student’s draft is being workshopped, pause and ask the other students to consider how their own papers might be developed or revised in terms of whatever issue is being discussed. If there’s time after, invite volunteers to share what they learned from the workshop that gave them an idea for improving their draft.

Choose drafts thematically: When choosing two drafts to workshop together in a given class session or week, pair your selections thematically, or in other suggestive ways, to create parallels and synergy between student workshops.

Turn the tables: Workshop the draft of a student whose early draft is strong but who tends to perceive their own writing as weak. This does double duty by building the student’s confidence while providing a strong model for other students in the class. (The method can also be reversed: workshop the problematic draft of an over-confident student to help them acknowledge and address its weaknesses.)

Return to sources: Ask students to bring to class all readings or sources that pertain to the writing assignment. In the midst of or near the end of the workshop, have the class locate passages in these sources that might help enrich—or complicate—the writer’s argument.

Forensic sketch artist: For research paper drafts, invite students to swap only their Works Cited pages with a partner. Ask them each to imagine what kind of an argument the other might be constructing on the basis of the sources alone. Then have them compare the sketch of the “suspect” to the author’s actual intention for the paper, identifying other source types that might usefully help fill in the picture.

Parallel workshops: Run two parallel workshops in separate rooms, shuttling between them. While the whole class will have read beforehand two students’ drafts, each group will discuss only the one they’ve been assigned to workshop. After thirty minutes or so, have the class reconvene in full to debrief about the generalizable lessons they have identified through the experience.

Dress rehearsal: Before the first real draft workshop of the semester, have the class practice the workshopping steps using a sample student paper. Following this dress rehearsal, invite students to collaborate on generating a list of criteria for what kind of feedback is most useful to receive on a draft. You can refer back to and refine this list throughout the semester.

From The Pocket Instructor: Writing , edited by Amanda Irwin Wilkins and Keith Shaw (Forthcoming, Princeton Univ. Press)

- Our Mission

Writing Workshop Checklist

Teaching a writing workshop can be scary, but this list of eight things you’ll need will help you get started.

I’ll admit that I was terrified to teach writing in a workshop format. Even after I successfully and happily conducted reading workshop with my classes, it took me another eight years to give writing workshop a try. There are some common problems that you might encounter , but in the end, writing workshop isn’t that difficult.

How to Go About It

Here are eight things you’ll need—some physical objects and some ideas and attitudes.

1. Freewriting prompts or other prewriting activities. Instructing students to just start writing a draft is a great way to end your experience with writing workshop very quickly. Instead, spend more time than you think you’ll need on prewriting. Get students going in a low-pressure way with freewriting prompts, research, brainstorming, or analyzing evidence or a primary source.

2. A clipboard or other method of keeping track of student progress daily. Walking around the room and checking in with students is a great way to keep a writing workshop on track. Checking specific process points off as students work is also much easier than dealing with multiple drafts and revisions at the end of the workshop. I also found it useful to write down students’ topics, in case I forgot. Create a process checklist and update as you go.

3. A willingness to stop micromanaging every part of the day. This was such a tough one for me. What if students start talking, and then they start talking more loudly, and then they break out the chips and party decorations and I have lost complete control of the room... The truth is that conducting a great writing workshop means letting go a little. Sometimes writers need breaks. It’s really difficult for teens to stay productive for an entire hour, so I had to work on being OK with not controlling every minute.

4. The ability to share documents in the moment. When I started, I’d have formal due dates for drafts, collect a huge stack of papers, and slowly work through them one by one. Eventually I switched to reading drafts as we went, during class time. This is easiest with Google Docs or another electronic means of sharing, but you can do it with paper copies too—computers are not a necessity. I could skim a draft in three minutes and let a student know if their main idea wasn’t clear or if the third paragraph needed more description. It made for some very busy classes, but it also cleared my desk of a giant stack of papers. Having that clipboard to keep track of whose drafts I’d read played a key role here.

5. Strategies to push students who resist revision. So many students are used to typing that last word and exclaiming, “Done!” But finishing the first draft is only a small part of the process of writing. Especially when kids are used to getting by with the bare minimum, it’s not easy to get them to go back to work that they see as already finished. Having specific suggestions for revision makes that process easier.

6. Examples of great writing. Save student work and look for published articles, essays, opinion pieces, poems—anything and everything you can find, so that when you need examples of smooth transitions, or conclusions that don’t say “in conclusion,” or grabbers that don’t ask cheesy rhetorical questions, you’ll have lots to choose from. For me, this was also a great excuse to read newspapers and magazines—you never know when you’ll find your next example.

7. Lots and lots of excitement for students’ ideas and experiences and voices. I’ve found that reluctant writers often feel like no one really cares about their experiences or ideas, so having lots of genuine excitement for students’ stories is important. Ultimately, their writing gave me a glimpse into what mattered to them, so it wasn’t hard to get excited about reading an essay about the school musical or the Brazilian wandering spider.

8. At least three more class days than you think you’ll need. Just about every teacher I’ve ever met feels a pressure to get through lots of material. But sometimes writing workshop just takes time. Some students might stare at their screen for three days and then write two pages in one burst, some might spend 20 minutes discussing the third sentence of their second paragraph in a peer conference, and some might need to describe every detail of the night before an event before they can actually get to writing about the real topic of their essay. Writing takes time, so make sure to leave plenty of space in your writing workshop schedule.

When I think back to my experiences with teaching writing workshop, I can remember students’ pieces and the excitement they felt when they figured out what their topic was or how to end their essay or the perfect word to describe the emotion they felt on the day in question. For me, the best reason to attempt writing workshop isn’t that it will help students become better writers—which it will—it’s that it will help them know themselves better.

- F.A.Q.s & Support

Family-Style Homeschooling

Writer’s Workshop Curriculum Guide

Layers of Learning’s Writer’s Workshop isn’t just a curriculum; it’s a mindset. It’s a lifestyle that will change writing from a chore to a joy as your whole family grows as writers together, family-school style.

To get you started on the right foot in this new mindset, we invite you to read the Writer’s Workshop Guidebook . It is written specifically for the parent or writing mentor. It will give you a clear picture of what Writer’s Workshop looks like and set you up for success.

After many, many years of teaching writing in this style, we share our best tips and an overall picture of what has worked well in our homeschools and co-ops, as well as provide detailed instructions for setting up a Writer’s Workshop and getting started with the units successfully.

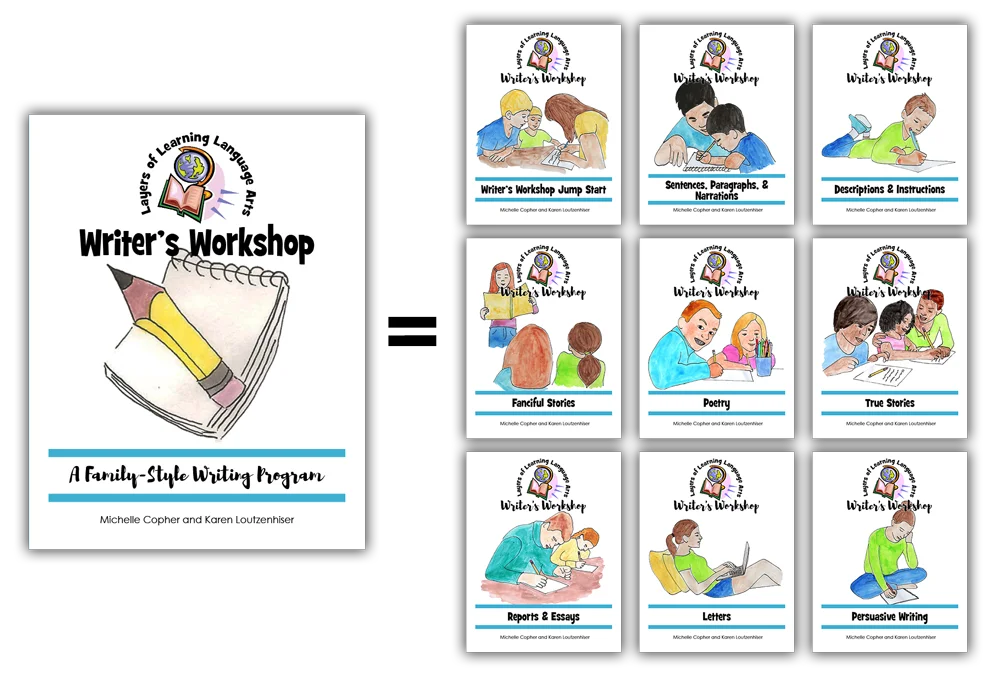

Nine Genre Units In One Reusable Program

The Writer’s Workshop program is divided into units based on different genres of writing including poetry, fanciful stories, report & essays, and so on.

Writer’s Workshop is sold two ways: as individual PDF units and as a single volume that includes all nine of the units.

Each genre unit is intended to last for about a month in your homeschool. You will pick and choose the parts you want to do, then be able to reuse it in subsequent years by choosing other exercises and writing projects from the same genre. Each unit can be used again and again in your family.

You can buy the entire program in one volume. Choose between a digital PDF download or a printed paperback version –>

Or Buy the Units One by One

Each unit included in the Writer’s Workshop program can also be purchased individually as PDFs. Here is what is included:

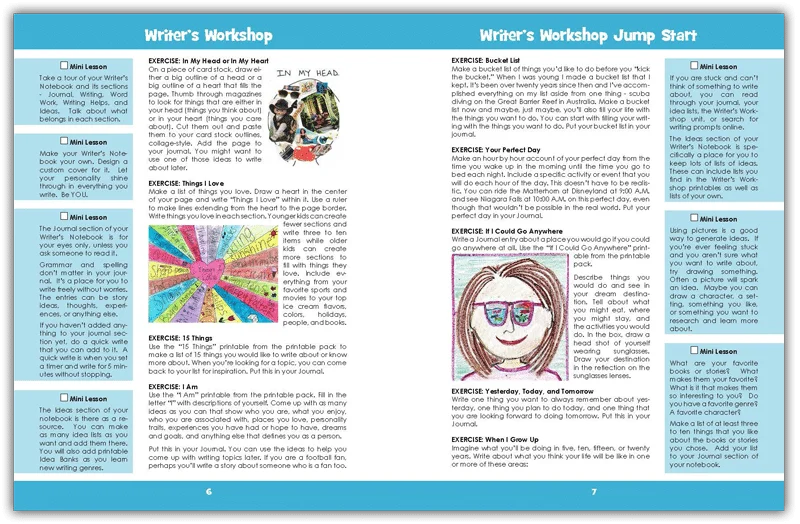

Writer’s Workshop Jump Start

We recommend using this at the beginning of each school year. It’s full of short writing exercises that are meant to spur on ideas and get kids in a creative, thoughtful groove. It also teaches the writing process and helps writers get settled into their Writer’s Notebooks.

Sentences, Paragraphs, & Narrations

This unit will get writers off on the right foot to crafting strong sentences and organized paragraphs. All of the content in it can be directly applied to what you’re learning about in other school subjects, so if you’ve been hoping to create greater unity between writing instruction and history, geography, science, and art, this is a great place to start. Along with learning how to write narrations, kids will learn how to write for tests.

Descriptions & Instructions

In this unit, you’ll get into the meat of what makes writing powerfully captivating. By using exact language, strong verbs, and sprinkling in figurative language, young writers will be able to capture interest in new ways. In addition, they will practice writing with precision.

Fanciful Stories

Fairy tales, superhero stories, fables, tall tales, and every other imaginary story falls into this really fun unit. Besides learning the structure and elements of a story, writers will also focus on surprising the audience and weaving in a theme, all through the lens of fiction.

Together, you will read and write poetry and play with words. Both formula poems and free verse will accompany your study of poetry terms, vivid language, and painting a picture with words.

True Stories

The flipside to Fanciful Stories, in True Stories you’ll learn biographies, autobiographies, articles, and personal narratives, You’ll also create an All About Me book and learn to journal about your life more effectively.

Reports & Essays

This unit will sharpen your skills as a serious writer. You will both research and share your own ideas as you learn to share the true things you know about. You’ll explore everything from animal reports to the ever-valuable five-paragraph essay and master what it takes to share true information in an organized way.

The Letter genre actually covers a lot more than just friendly letters. You’ll learn how to write and send e-mail, create a resume, fill out forms, and write a letter to the editor, among other valuable correspondence skills.

Persuasive Writing

The art of persuasion will be practiced through lots of forms in this unit, from convincing your parents to let you stay up late to writing a full-blown persuasive essay. You’ll learn the tricks to writing in a convincing, memorable way.

Research Paper

The Research Paper unit is the only one that is written specifically for teens. This step-by-step guide will teach teens how to write a full-blown research paper, one bit at a time.

Research Paper is sold only as a PDF and is not included in the single volume Writer’s Workshop.

Inside Each Unit

Within each unit , you will find exercises – short writing assignments that help you develop specific writing skills. None of the exercises will be graded. They are practice. Most of these will be kept within a Journal that is personal to each writer. Creativity and freedom of expression are hallmarks of a successful Writer’s Workshop.

Mini-Lessons

Accompanying the exercises, there are sidebars within each unit that share mini-lessons, short daily lessons to help teach grammar, punctuation, the writing process, genre skills, and more. Mentors are also encouraged to be an active member of the Writer’s Workshop, noticing skills that need to be taught and tailoring the program to help growing writers. In addition, within the Layers of Learning catalog , you can click on the unit you are using and have access to more links, the unit’s YouTube playlist, and the continually-growing Writer’s Workshop Pinterest board.

Project Ideas Banks

During the course of each unit , one project will be chosen and the writer will take that one piece all of the way through the writing process – prewriting, drafting, revising, editing, and publishing. Every unit includes idea banks to spur on ideas and keep pens to paper. The monthly project will be the only graded writing, and its evaluation includes a rubric that addresses specific skills learned within the unit.

Every single Writer’s Workshop unit also includes a printable pack full of printables used within the exercises and mini-lessons, as well as printable idea banks and rubrics.

Word Work is a spelling and vocabulary program for 6 years old to 18 years old. It is also a constant companion to all of the other units.

Word Work includes:

- spelling lists

- vocabulary lists

- spelling activity ideas

- worksheets to use with any spelling list

It is sold only as a digital PDF download.

You will begin each day with a short session of mastering words, including both spelling and vocabulary.

Word Work allows kids to master the words that will be their medium for sharing the ideas they have.

The Goal of Writer’s Workshop

Writing in our homeschool happens in short bursts throughout our day. We use it to show what we know and add our own ideas and contributions to the world’s body of knowledge. Writing is empowering! Rather than getting caught up in mechanics and mundane exercises, we focus on ideas first. We use writing to communicate, to share a part of ourselves and our ideas.

Process Over Product

As we write, we focus on the process, not just the product. Writer’s Workshop Jump Start will help kids practice the writing process, which they will continue to use as they write.

- pre-writing

Just to be clear, these steps don’t all happen in a day, and sometimes they don’t all happen in a week. I teach mini-lessons just about every day. We write in our writer’s notebooks until we have something we want to turn into more. Sometimes this happens spontaneously (like my son’s series of Super Monkey books about a superhero monkey who saves the world from a variety of evil-doers). Sometimes it happens because I assign something; “Okay young authors, your biography is due on Friday. . . no more dawdling!”)

The kids write, wherever they are at in the process, until we are ready to move on to something else. Then they just put it away and pick up where they left off the next day.

Some Quick Tips

Open creativity is awesome, but we’re also believers in providing clear direction. There’s nothing worse than being told to write anything at all when no ideas seem to come. Some kids will come up with their own ideas, but you should also have assignments, story starters, fun ideas, and specific directions on hand for those writers who don’t come up with topics and ideas well on their own. The Writer’s Workshop units are a go-to source of inspiration for those tidbits of fun.

The physical act of writing can be quite a chore for some kids. Don’t take the burden away entirely, because the way they will build writing endurance is by writing. At the same time, you can lighten the burden. For example, taking a story all the way through the writing process can involve three or more re-writes. Have kids do it once, but then you can pitch in and type up the story. With little ones, you may even do some of their writing on the first draft to help them get their ideas down, but don’t ever take over and do all the writing if you want them to grow as writers.

Pre-writing is an important first step in the writing process. Talking about ideas, drawing a picture, creating a character sketch, or making a web or outline can make an overwhelming assignment manageable. A fun pre-writing activity is a great mini-lesson with each new genre you start .

Intersperse writing assignments with authentic writing experiences. Kids can write to grandparents, penpals, people in the community, companies, authors, and politicians. They can write shopping lists and to-do lists, or send e-mail . Consider submitting essays to essay contests, writing online book reviews, or keeping a family scrapbook.

Every day is different and variety is key. Sometimes we’re quietly writing at desks. Sometimes we’re outside listing as many things as we can see in our yard together. You may find me typing up a story with a kid at my side as we talk about how to make the writing better. You may see us all sitting together writing a collective story, with Mom as the scribe . Sometimes we’re reading silly poems together. We could be playing a game about nouns or watching Grammar Rock videos. We’re always reading, writing, and talking about writing. In the messy process (and about an hour a day), we become better writers by doing Writer’s Workshop.

We Hope You’ll Join Us!

We write all throughout our day, whether we’re writing what we learned about an artist, explaining a math concept in a journal entry, writing up an experiment, or creating a passage in our world explorer journals. Our Writer’s Workshop gives us the flexibility to write about anything we have big ideas about. As we master the writing process and learn how to be better writers, we get to use those skills to better share the ideas we have. Through Writer’s Workshop, we grow! We hope you’ll join us in creating a Writer’s Workshop in your homeschool. We can’t wait to see the ways you grow too!

Writer’s Workshop in a Podcast

Want to hear Karen and Michelle chat about Writer’s Workshop? Listen in on their Writer’s Workshop podcast episode . Michelle picked Karen’s brain a bit about how Writer’s Workshop came about and what it looks like in her homeschool.

18 thoughts on “Writer’s Workshop Curriculum Guide”

Excellent job Layers of Learning. These ideas will work wonderfully with my Deaf students. Writing is a major challenge for them but these strategies and fun activities are just what they need. Thanks.

Hi Michelle!

How can I get access to this guide?

You’ll find the complete Guidebook in the Writer’s Workshop section of the Layers of Learning catalog. https://layers-of-learning.com/shop/writers-workshop/digital-pdf/guidebook-how-to-create-a-writers-workshop/

is there a plan to put out curriculum guides for the other genres?

Yes! The other guides will be coming out over the next year.

My children have never had formal Grammer. Do you suggest a Grammer supplement for my oldest, a 6/7th grader? Something that starts from the beginning but will get her up to speed.

Maranda, You don’t necessarily have to do formal grammar. Writer’s Workshop style is to teach “mini lessons” which include grammar and writing skills. The mini lessons are tailored by you to what your children need to learn. There are sidebars with lesson ideas all through the Writer’s Workshop program. But if you are feeling unsure about grammar rules yourself and unable to spot where and how corrections need to be made in your children’s work, then we recommend purchasing a simple inexpensive grammar workbook and going through it as a family, not necessarily doing the whole workbook, but using it as the “mini lessons” until you all feel up to speed. Something like English & Grammar 6 would be appropriate for the whole family to work on together.

Hi, my son is in second grade and I’m looking for a writing program for him and this looks great! Do I also need a separate Language Arts curriculum? Also, is this all meant to be done in one year? Or how do I go about pacing it? Thanks!

You don’t need a separate Langauge Arts curriculum. You will want to track what he’s reading, but this includes the writing, grammar, and spelling (if you use the Word Work component). Each unit is intended to be used for a month of instruction, so you’ll purchase one unit per month. There is a lot more there than you will have time to do within the month, but it is intended to be used again the following year, with you choosing new exercises the next time around. Hope that helps!

How does she Writer’s workshop compare to Brave Writer?

Personally, we have not used Brave Writer, but this would be a great question to ask within the Layers of Learning Facebook Group. There are a number of families there who have used both. From their descriptions, the lifestyle is the same, but the process is different. Writer’s Workshop has more specific prompts and daily writing suggestions to help kids get creative juices flowing.

Thank you for your reply !

Is there a version of this for high school-aged kids? If not what would you recommend?

There are activities included in Writer’s Workshop for high schoolers. You’ll find a variety of things for all ages in every single unit. One unit, The Research Paper, is specifically for high school-aged kids.

I am homeschooling gr1, 3,5,6. Will this work across the grade? I need only one resource for the whole family or are there consumables I need to buy for each child??

Writer’s Workshop is for your whole family. You will find ideas and resources in there for kids ages 6-18. It comes with a Printable Pack that includes the consumable printables. You will need to print them as needed for your kids, but you only need to purchase one Writer’s Workshop and can print as many as you need for your family.

I would like my 15 year old to be ready to write college level papers. I haven’t used your program before. Can I start with Research Paper level? Thanks!

The Research Paper walks teens through the process of writing a research paper. It doesn’t include other writing instruction and assumes that the student is skilled in reading, writing, and working independently. I’m not sure what your son’s skill level is at or what experiences he’s had. If he hasn’t worked with taking pieces of writing through the writing process independently yet, I would recommend starting with Jump Start, working through Reports & Essays, and then proceeding to The Research Paper. Only you know what your son’s writing level and experience are though.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- ATL Tools & Resources

Writer’s Workshop Feedback Strategies

Sharing with no response.

This strategy works during any stage of the writing process. It allows the writer to respond to their writing without having to think about how others might respond. Another benefit of this strategy is that it draws on the writer’s listening skills—skills that are often silenced during the writing process. When hearing their writing, writers tend to see more. This makes identifying areas for improvement a much easier. Writers may choose to read it aloud themselves or have someone else read it aloud. This forces the writer to rely entirely on their listening skills. This strategy can also be used outside a workshop setting—at home in front of a mirror or with a family member. To use this strategy, complete the following steps:

- Before you begin, read the description of the strategy above to group members.

- Remind members that they do not need to respond. Instead, they only need to listen.

- As you read, listen for areas that you think could be improved. When you notice one, circle or highlight it. Feel free to pause periodically if you need more time to highlight. If someone else is reading for you, do not to read along with your own copy. Instead, note areas for improvement on a blank piece of paper. This will force you to rely on your listening skills more.

- If time permits, you may choose to read it aloud again.

This strategy works well during the early drafting stage of the writing process. Writers use this strategy to get help identifying strengths in their writing that they can then build upon. It is also useful for boosting a writer’s confidence. When using this strategy, group members read along with the writer and highlight or circle sentences that they think work well. Writers can ask group members to focus on explanation of the ideas, the sequencing or the way the sentences are written. Writers who want a little constructive feedback may ask group members to point to one areas for improvement for every two strengths they identify. To use this strategy, complete the following steps:

- Share copies of your writing with group members.

- Explain which area of your writing you would like members to focus on—‘what’ you are trying to say and/or ‘how’ you are trying to say it.

- Ask members to underline or highlight specific sentences that seem particularly strong as they read along. You should also highlight sentences that stand out to you.

- Read your writing aloud a second time. As members listen again, ask them to choose the strongest 2-3 sentences from the ones they highlighted. Be sure to also choose your top 2-3.

- Once you have finished reading a second time, ask group members to take turns pointing out which 2-3 sentences they selected. Members should point to a sentence, read it aloud and then explain why they selected it.

TALKING IT OUT

This strategy works best during the prewriting stage of the writing process. It is useful for writers who are unsure about what to write or simply want to explore some ideas before getting started. When using this strategy, the writer shares ideas with the group and invites input from the group. Group members may ask questions to help stimulate thinking or offer suggestions. The writer may also ask members to simply listen without responding. If you’re in a writer’s workshop, be sure to set a time limit of 10-15 minutes so other members of the group have an opportunity to share their writing. To use this strategy, complete the following steps:

- Set a timer for 10-15 minutes.

- Tell group members how you would like them to respond. Would you like them to ask questions? Offer suggestions? Or simply listen?

- Ask group members to consider the sentence starter below if they need help

- Explain what ideas you have about your topic simply by saying, “I’m thinking about writing about ______. What do you think? Or “I’m thinking about saying X, Y, and Z. What do you think?

- As you and members discuss your ideas, be sure to take notes. You can use these notes to get started writing later.

- What do you think/know about __________?

- I liked ___________, but maybe you should consider ___________ because ______________.

- Have you thought about ________________ because ___________.

- I think ___________ would be interesting to explore because ____________.

- Though I agree with __________________ because ___________, I do not agree with _________ because _________.

PARAPHRASING

This strategy works best during the drafting stage of the writing process. It helps writers work on the explanation and sequencing of their ideas. Paraphrasing is a summary of an original text—something written or said. Paraphrases should be shorter than the original and they should be done mostly in the paraphraser’s own words, though they will likely include key words and phrases from the original. Paraphrasing allows writers to see how others hear their writing and it allows them to test if their writing is actually says what they think it does.

When using this strategy, the writer reads aloud chunks of their writing and pauses in between chunks so group members can paraphrase what they just heard. It is important that group members take notes as they listen. They should also be take time when pausing to generate their paraphrase. Taking notes and pausing ensures that group members are using their own language and not the language of other group members. Before getting started, the writer will need to decide how they will break the writing into chunks. Smaller chunks allow for more detailed feedback. Writers may choose to chunk point by point or paragraph by paragraph. Writers may choose larger chunks if they are not ready for more detailed feedback. If the workshop group is larger, the writer should focus on one chunk only—the chunk they need to most help developing. To use this strategy, complete the following steps:

- Before you begin, look through your writing and break it into chunks by drawing lines across the paper to separate the chunks.

- Once you’ve chunked your writing, read the description of the strategy above to group members.

- Inform members that you will not be sharing a paper copy of your writing.

- Remind group members not to focus on editing—no grammar, punctuation, spelling, etc.

- Explain to group members how you have chunked your writing—point by point, paragraph by paragraph, etc.

- Remind them to take notes as they listen and to use some of your language—like key words—but mostly their own.

- Read a chunk aloud. Remember to read slowly enough so that the listeners can follow along.

- Pause for a 1-2 minutes to allow members to generate a paraphrase. Remind member that they should use some of the writer’s language but mostly rely on their own.

- Ask group members to share their paraphrases one at a time. (If you find that most members are having difficulty paraphrasing a particular chunk, you may choose to read it aloud again.)

- Repeat steps 7 – 9 until you’ve finished reading all your chunks.

- What I heard you say is ___________________.

- The main thing or almost main thing you said was _________________.

- What I think I heard you say is _____________.

- Did you say _____________?

WHAT’S ALMOST SAID & WHAT’S MISSING

This strategy works well during the early drafting stage of the writing process. Writers use it when they sense more is needed to make their writing better but haven’t been able to put their finger on what exactly it is yet. This strategy helps writers pinpoint areas they can improve by asking group members to provide concrete suggestions. When using this strategy, group members get a paper copy of the writer’s work and follow along as the writer reads it aloud. Group members highlight or circle sentences containing ideas that are not fully explained or that they would like to hear more about. Members write brief explanations in the margin and offer suggestions for how the writer could improve. This strategy can take approximately 20 minutes per writer as it requires the writer to read their work aloud two times. To use this strategy, complete the following steps:

- Before you begin, read the description above and the steps below to group members.

- Be sure each member of the group has paper copy of your writing and something to write with.

- Remind group members that they should not give feedback on editing—no grammar, punctuation, spelling, etc.

- Instruct group members to highlight or circle any sentences containing ideas that are not fully explained or that they would like to hear more about. Members may write suggestions for new ideas

- Read your writing aloud. Remember to read slowly enough so that the listeners can follow along.

- Once you’ve finished reading the first time, pause for 3 minutes to give members an opportunity write down some explanations and suggestions.

- Read your writing aloud again.

- Once you’ve finished, pause again for 3 minutes to give members an opportunity write down some explanations and suggestions.

- Ask each group member to select 2 sentences they highlighted for improvement. One at time, group members should point to a sentence they selected, explain why they selected it and offer suggestions.

- “I highlighted the sentence on page ____ in paragraph _____. The sentence starts with _______. (Read it aloud.)” Now choose one of these sentence starters:

- I wanted to hear more about _____________ because _____________. I think you could improve this by discussing _________ more.

- Have you considered introducing or adding the idea of ___________. This might help because ________.

This strategy works best during the drafting stage of the writing process. It is particularly useful for writers trying to find weaknesses in their argument or trying to develop a successful counterargument. When using this strategy, group members pretend to oppose the writer’s argument and challenge every statement and claim the writers makes—their overall position, selection of evidence, explanations, analyses and conclusions. Group members may even challenge the use of specific language if they find it is inaccurate. As they read along with the writer, group members write objections and counterarguments in the margins. This strategy can take approximately 15 minutes per writer as it requires the writer to read their work aloud two times. To use this strategy, complete the following steps:

- Instruct group members to highlight or circle anything they think the opposition would challenge. They should then write a brief explanation or counterargument in the margins.

- Once you’ve finished reading the first time, pause for 3 minutes to give members an opportunity to continue writing their explanations and counterarguments in the margins.

- Once you’ve finished, pause for 3 minutes to give members an opportunity to continue writing their explanations and counterarguments in the margins.

- On page ____ in paragraph _____, you wrote __________. The opposition might disagree with this because ________.

- On page ____ in paragraph _____, you wrote __________. The opposition could challenge this by stating _______.

This strategy works best during the drafting stage of the writing process. It is particularly useful for writers trying to find strengths in their writing. When using this strategy, group members pretend to support the writer’s argument by agreeing with every statement and claim the writers makes—their overall position, selection of evidence, explanations, analyses and conclusions. Group members may even support the use of specific language if they find it is. As they read along with the writer, group members write in the margins supporting statements and possible ways the writing can further strengthen their argument. This strategy can take approximately 15 minutes per writer as it requires the writer to read their work aloud two times. To use this strategy, complete the following steps:

- Instruct group members to highlight or circle anything they agree with. They should then write a brief explanation or counterargument in the margins using the following sentence templates: “I agree with ______ because ______” and “I agree with ______ and think it would be strengthened if you added ___________.”

- Once you’ve finished reading the first time, pause for 3 minutes to give members an opportunity to continue writing their supporting statements in the margins.

- Once you’ve finished, pause for 3 minutes to give members an opportunity to continue writing their supporting statements in the margins.