Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

Definition and Introduction

Case analysis is a problem-based teaching and learning method that involves critically analyzing complex scenarios within an organizational setting for the purpose of placing the student in a “real world” situation and applying reflection and critical thinking skills to contemplate appropriate solutions, decisions, or recommended courses of action. It is considered a more effective teaching technique than in-class role playing or simulation activities. The analytical process is often guided by questions provided by the instructor that ask students to contemplate relationships between the facts and critical incidents described in the case.

Cases generally include both descriptive and statistical elements and rely on students applying abductive reasoning to develop and argue for preferred or best outcomes [i.e., case scenarios rarely have a single correct or perfect answer based on the evidence provided]. Rather than emphasizing theories or concepts, case analysis assignments emphasize building a bridge of relevancy between abstract thinking and practical application and, by so doing, teaches the value of both within a specific area of professional practice.

Given this, the purpose of a case analysis paper is to present a structured and logically organized format for analyzing the case situation. It can be assigned to students individually or as a small group assignment and it may include an in-class presentation component. Case analysis is predominately taught in economics and business-related courses, but it is also a method of teaching and learning found in other applied social sciences disciplines, such as, social work, public relations, education, journalism, and public administration.

Ellet, William. The Case Study Handbook: A Student's Guide . Revised Edition. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2018; Christoph Rasche and Achim Seisreiner. Guidelines for Business Case Analysis . University of Potsdam; Writing a Case Analysis . Writing Center, Baruch College; Volpe, Guglielmo. "Case Teaching in Economics: History, Practice and Evidence." Cogent Economics and Finance 3 (December 2015). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2015.1120977.

How to Approach Writing a Case Analysis Paper

The organization and structure of a case analysis paper can vary depending on the organizational setting, the situation, and how your professor wants you to approach the assignment. Nevertheless, preparing to write a case analysis paper involves several important steps. As Hawes notes, a case analysis assignment “...is useful in developing the ability to get to the heart of a problem, analyze it thoroughly, and to indicate the appropriate solution as well as how it should be implemented” [p.48]. This statement encapsulates how you should approach preparing to write a case analysis paper.

Before you begin to write your paper, consider the following analytical procedures:

- Review the case to get an overview of the situation . A case can be only a few pages in length, however, it is most often very lengthy and contains a significant amount of detailed background information and statistics, with multilayered descriptions of the scenario, the roles and behaviors of various stakeholder groups, and situational events. Therefore, a quick reading of the case will help you gain an overall sense of the situation and illuminate the types of issues and problems that you will need to address in your paper. If your professor has provided questions intended to help frame your analysis, use them to guide your initial reading of the case.

- Read the case thoroughly . After gaining a general overview of the case, carefully read the content again with the purpose of understanding key circumstances, events, and behaviors among stakeholder groups. Look for information or data that appears contradictory, extraneous, or misleading. At this point, you should be taking notes as you read because this will help you develop a general outline of your paper. The aim is to obtain a complete understanding of the situation so that you can begin contemplating tentative answers to any questions your professor has provided or, if they have not provided, developing answers to your own questions about the case scenario and its connection to the course readings,lectures, and class discussions.

- Determine key stakeholder groups, issues, and events and the relationships they all have to each other . As you analyze the content, pay particular attention to identifying individuals, groups, or organizations described in the case and identify evidence of any problems or issues of concern that impact the situation in a negative way. Other things to look for include identifying any assumptions being made by or about each stakeholder, potential biased explanations or actions, explicit demands or ultimatums , and the underlying concerns that motivate these behaviors among stakeholders. The goal at this stage is to develop a comprehensive understanding of the situational and behavioral dynamics of the case and the explicit and implicit consequences of each of these actions.

- Identify the core problems . The next step in most case analysis assignments is to discern what the core [i.e., most damaging, detrimental, injurious] problems are within the organizational setting and to determine their implications. The purpose at this stage of preparing to write your analysis paper is to distinguish between the symptoms of core problems and the core problems themselves and to decide which of these must be addressed immediately and which problems do not appear critical but may escalate over time. Identify evidence from the case to support your decisions by determining what information or data is essential to addressing the core problems and what information is not relevant or is misleading.

- Explore alternative solutions . As noted, case analysis scenarios rarely have only one correct answer. Therefore, it is important to keep in mind that the process of analyzing the case and diagnosing core problems, while based on evidence, is a subjective process open to various avenues of interpretation. This means that you must consider alternative solutions or courses of action by critically examining strengths and weaknesses, risk factors, and the differences between short and long-term solutions. For each possible solution or course of action, consider the consequences they may have related to their implementation and how these recommendations might lead to new problems. Also, consider thinking about your recommended solutions or courses of action in relation to issues of fairness, equity, and inclusion.

- Decide on a final set of recommendations . The last stage in preparing to write a case analysis paper is to assert an opinion or viewpoint about the recommendations needed to help resolve the core problems as you see them and to make a persuasive argument for supporting this point of view. Prepare a clear rationale for your recommendations based on examining each element of your analysis. Anticipate possible obstacles that could derail their implementation. Consider any counter-arguments that could be made concerning the validity of your recommended actions. Finally, describe a set of criteria and measurable indicators that could be applied to evaluating the effectiveness of your implementation plan.

Use these steps as the framework for writing your paper. Remember that the more detailed you are in taking notes as you critically examine each element of the case, the more information you will have to draw from when you begin to write. This will save you time.

NOTE : If the process of preparing to write a case analysis paper is assigned as a student group project, consider having each member of the group analyze a specific element of the case, including drafting answers to the corresponding questions used by your professor to frame the analysis. This will help make the analytical process more efficient and ensure that the distribution of work is equitable. This can also facilitate who is responsible for drafting each part of the final case analysis paper and, if applicable, the in-class presentation.

Framework for Case Analysis . College of Management. University of Massachusetts; Hawes, Jon M. "Teaching is Not Telling: The Case Method as a Form of Interactive Learning." Journal for Advancement of Marketing Education 5 (Winter 2004): 47-54; Rasche, Christoph and Achim Seisreiner. Guidelines for Business Case Analysis . University of Potsdam; Writing a Case Study Analysis . University of Arizona Global Campus Writing Center; Van Ness, Raymond K. A Guide to Case Analysis . School of Business. State University of New York, Albany; Writing a Case Analysis . Business School, University of New South Wales.

Structure and Writing Style

A case analysis paper should be detailed, concise, persuasive, clearly written, and professional in tone and in the use of language . As with other forms of college-level academic writing, declarative statements that convey information, provide a fact, or offer an explanation or any recommended courses of action should be based on evidence. If allowed by your professor, any external sources used to support your analysis, such as course readings, should be properly cited under a list of references. The organization and structure of case analysis papers can vary depending on your professor’s preferred format, but its structure generally follows the steps used for analyzing the case.

Introduction

The introduction should provide a succinct but thorough descriptive overview of the main facts, issues, and core problems of the case . The introduction should also include a brief summary of the most relevant details about the situation and organizational setting. This includes defining the theoretical framework or conceptual model on which any questions were used to frame your analysis.

Following the rules of most college-level research papers, the introduction should then inform the reader how the paper will be organized. This includes describing the major sections of the paper and the order in which they will be presented. Unless you are told to do so by your professor, you do not need to preview your final recommendations in the introduction. U nlike most college-level research papers , the introduction does not include a statement about the significance of your findings because a case analysis assignment does not involve contributing new knowledge about a research problem.

Background Analysis

Background analysis can vary depending on any guiding questions provided by your professor and the underlying concept or theory that the case is based upon. In general, however, this section of your paper should focus on:

- Providing an overarching analysis of problems identified from the case scenario, including identifying events that stakeholders find challenging or troublesome,

- Identifying assumptions made by each stakeholder and any apparent biases they may exhibit,

- Describing any demands or claims made by or forced upon key stakeholders, and

- Highlighting any issues of concern or complaints expressed by stakeholders in response to those demands or claims.

These aspects of the case are often in the form of behavioral responses expressed by individuals or groups within the organizational setting. However, note that problems in a case situation can also be reflected in data [or the lack thereof] and in the decision-making, operational, cultural, or institutional structure of the organization. Additionally, demands or claims can be either internal and external to the organization [e.g., a case analysis involving a president considering arms sales to Saudi Arabia could include managing internal demands from White House advisors as well as demands from members of Congress].

Throughout this section, present all relevant evidence from the case that supports your analysis. Do not simply claim there is a problem, an assumption, a demand, or a concern; tell the reader what part of the case informed how you identified these background elements.

Identification of Problems

In most case analysis assignments, there are problems, and then there are problems . Each problem can reflect a multitude of underlying symptoms that are detrimental to the interests of the organization. The purpose of identifying problems is to teach students how to differentiate between problems that vary in severity, impact, and relative importance. Given this, problems can be described in three general forms: those that must be addressed immediately, those that should be addressed but the impact is not severe, and those that do not require immediate attention and can be set aside for the time being.

All of the problems you identify from the case should be identified in this section of your paper, with a description based on evidence explaining the problem variances. If the assignment asks you to conduct research to further support your assessment of the problems, include this in your explanation. Remember to cite those sources in a list of references. Use specific evidence from the case and apply appropriate concepts, theories, and models discussed in class or in relevant course readings to highlight and explain the key problems [or problem] that you believe must be solved immediately and describe the underlying symptoms and why they are so critical.

Alternative Solutions

This section is where you provide specific, realistic, and evidence-based solutions to the problems you have identified and make recommendations about how to alleviate the underlying symptomatic conditions impacting the organizational setting. For each solution, you must explain why it was chosen and provide clear evidence to support your reasoning. This can include, for example, course readings and class discussions as well as research resources, such as, books, journal articles, research reports, or government documents. In some cases, your professor may encourage you to include personal, anecdotal experiences as evidence to support why you chose a particular solution or set of solutions. Using anecdotal evidence helps promote reflective thinking about the process of determining what qualifies as a core problem and relevant solution .

Throughout this part of the paper, keep in mind the entire array of problems that must be addressed and describe in detail the solutions that might be implemented to resolve these problems.

Recommended Courses of Action

In some case analysis assignments, your professor may ask you to combine the alternative solutions section with your recommended courses of action. However, it is important to know the difference between the two. A solution refers to the answer to a problem. A course of action refers to a procedure or deliberate sequence of activities adopted to proactively confront a situation, often in the context of accomplishing a goal. In this context, proposed courses of action are based on your analysis of alternative solutions. Your description and justification for pursuing each course of action should represent the overall plan for implementing your recommendations.

For each course of action, you need to explain the rationale for your recommendation in a way that confronts challenges, explains risks, and anticipates any counter-arguments from stakeholders. Do this by considering the strengths and weaknesses of each course of action framed in relation to how the action is expected to resolve the core problems presented, the possible ways the action may affect remaining problems, and how the recommended action will be perceived by each stakeholder.

In addition, you should describe the criteria needed to measure how well the implementation of these actions is working and explain which individuals or groups are responsible for ensuring your recommendations are successful. In addition, always consider the law of unintended consequences. Outline difficulties that may arise in implementing each course of action and describe how implementing the proposed courses of action [either individually or collectively] may lead to new problems [both large and small].

Throughout this section, you must consider the costs and benefits of recommending your courses of action in relation to uncertainties or missing information and the negative consequences of success.

The conclusion should be brief and introspective. Unlike a research paper, the conclusion in a case analysis paper does not include a summary of key findings and their significance, a statement about how the study contributed to existing knowledge, or indicate opportunities for future research.

Begin by synthesizing the core problems presented in the case and the relevance of your recommended solutions. This can include an explanation of what you have learned about the case in the context of your answers to the questions provided by your professor. The conclusion is also where you link what you learned from analyzing the case with the course readings or class discussions. This can further demonstrate your understanding of the relationships between the practical case situation and the theoretical and abstract content of assigned readings and other course content.

Problems to Avoid

The literature on case analysis assignments often includes examples of difficulties students have with applying methods of critical analysis and effectively reporting the results of their assessment of the situation. A common reason cited by scholars is that the application of this type of teaching and learning method is limited to applied fields of social and behavioral sciences and, as a result, writing a case analysis paper can be unfamiliar to most students entering college.

After you have drafted your paper, proofread the narrative flow and revise any of these common errors:

- Unnecessary detail in the background section . The background section should highlight the essential elements of the case based on your analysis. Focus on summarizing the facts and highlighting the key factors that become relevant in the other sections of the paper by eliminating any unnecessary information.

- Analysis relies too much on opinion . Your analysis is interpretive, but the narrative must be connected clearly to evidence from the case and any models and theories discussed in class or in course readings. Any positions or arguments you make should be supported by evidence.

- Analysis does not focus on the most important elements of the case . Your paper should provide a thorough overview of the case. However, the analysis should focus on providing evidence about what you identify are the key events, stakeholders, issues, and problems. Emphasize what you identify as the most critical aspects of the case to be developed throughout your analysis. Be thorough but succinct.

- Writing is too descriptive . A paper with too much descriptive information detracts from your analysis of the complexities of the case situation. Questions about what happened, where, when, and by whom should only be included as essential information leading to your examination of questions related to why, how, and for what purpose.

- Inadequate definition of a core problem and associated symptoms . A common error found in case analysis papers is recommending a solution or course of action without adequately defining or demonstrating that you understand the problem. Make sure you have clearly described the problem and its impact and scope within the organizational setting. Ensure that you have adequately described the root causes w hen describing the symptoms of the problem.

- Recommendations lack specificity . Identify any use of vague statements and indeterminate terminology, such as, “A particular experience” or “a large increase to the budget.” These statements cannot be measured and, as a result, there is no way to evaluate their successful implementation. Provide specific data and use direct language in describing recommended actions.

- Unrealistic, exaggerated, or unattainable recommendations . Review your recommendations to ensure that they are based on the situational facts of the case. Your recommended solutions and courses of action must be based on realistic assumptions and fit within the constraints of the situation. Also note that the case scenario has already happened, therefore, any speculation or arguments about what could have occurred if the circumstances were different should be revised or eliminated.

Bee, Lian Song et al. "Business Students' Perspectives on Case Method Coaching for Problem-Based Learning: Impacts on Student Engagement and Learning Performance in Higher Education." Education & Training 64 (2022): 416-432; The Case Analysis . Fred Meijer Center for Writing and Michigan Authors. Grand Valley State University; Georgallis, Panikos and Kayleigh Bruijn. "Sustainability Teaching using Case-Based Debates." Journal of International Education in Business 15 (2022): 147-163; Hawes, Jon M. "Teaching is Not Telling: The Case Method as a Form of Interactive Learning." Journal for Advancement of Marketing Education 5 (Winter 2004): 47-54; Georgallis, Panikos, and Kayleigh Bruijn. "Sustainability Teaching Using Case-based Debates." Journal of International Education in Business 15 (2022): 147-163; .Dean, Kathy Lund and Charles J. Fornaciari. "How to Create and Use Experiential Case-Based Exercises in a Management Classroom." Journal of Management Education 26 (October 2002): 586-603; Klebba, Joanne M. and Janet G. Hamilton. "Structured Case Analysis: Developing Critical Thinking Skills in a Marketing Case Course." Journal of Marketing Education 29 (August 2007): 132-137, 139; Klein, Norman. "The Case Discussion Method Revisited: Some Questions about Student Skills." Exchange: The Organizational Behavior Teaching Journal 6 (November 1981): 30-32; Mukherjee, Arup. "Effective Use of In-Class Mini Case Analysis for Discovery Learning in an Undergraduate MIS Course." The Journal of Computer Information Systems 40 (Spring 2000): 15-23; Pessoa, Silviaet al. "Scaffolding the Case Analysis in an Organizational Behavior Course: Making Analytical Language Explicit." Journal of Management Education 46 (2022): 226-251: Ramsey, V. J. and L. D. Dodge. "Case Analysis: A Structured Approach." Exchange: The Organizational Behavior Teaching Journal 6 (November 1981): 27-29; Schweitzer, Karen. "How to Write and Format a Business Case Study." ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/how-to-write-and-format-a-business-case-study-466324 (accessed December 5, 2022); Reddy, C. D. "Teaching Research Methodology: Everything's a Case." Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 18 (December 2020): 178-188; Volpe, Guglielmo. "Case Teaching in Economics: History, Practice and Evidence." Cogent Economics and Finance 3 (December 2015). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2015.1120977.

Writing Tip

Ca se Study and Case Analysis Are Not the Same!

Confusion often exists between what it means to write a paper that uses a case study research design and writing a paper that analyzes a case; they are two different types of approaches to learning in the social and behavioral sciences. Professors as well as educational researchers contribute to this confusion because they often use the term "case study" when describing the subject of analysis for a case analysis paper. But you are not studying a case for the purpose of generating a comprehensive, multi-faceted understanding of a research problem. R ather, you are critically analyzing a specific scenario to argue logically for recommended solutions and courses of action that lead to optimal outcomes applicable to professional practice.

To avoid any confusion, here are twelve characteristics that delineate the differences between writing a paper using the case study research method and writing a case analysis paper:

- Case study is a method of in-depth research and rigorous inquiry ; case analysis is a reliable method of teaching and learning . A case study is a modality of research that investigates a phenomenon for the purpose of creating new knowledge, solving a problem, or testing a hypothesis using empirical evidence derived from the case being studied. Often, the results are used to generalize about a larger population or within a wider context. The writing adheres to the traditional standards of a scholarly research study. A case analysis is a pedagogical tool used to teach students how to reflect and think critically about a practical, real-life problem in an organizational setting.

- The researcher is responsible for identifying the case to study; a case analysis is assigned by your professor . As the researcher, you choose the case study to investigate in support of obtaining new knowledge and understanding about the research problem. The case in a case analysis assignment is almost always provided, and sometimes written, by your professor and either given to every student in class to analyze individually or to a small group of students, or students select a case to analyze from a predetermined list.

- A case study is indeterminate and boundless; a case analysis is predetermined and confined . A case study can be almost anything [see item 9 below] as long as it relates directly to examining the research problem. This relationship is the only limit to what a researcher can choose as the subject of their case study. The content of a case analysis is determined by your professor and its parameters are well-defined and limited to elucidating insights of practical value applied to practice.

- Case study is fact-based and describes actual events or situations; case analysis can be entirely fictional or adapted from an actual situation . The entire content of a case study must be grounded in reality to be a valid subject of investigation in an empirical research study. A case analysis only needs to set the stage for critically examining a situation in practice and, therefore, can be entirely fictional or adapted, all or in-part, from an actual situation.

- Research using a case study method must adhere to principles of intellectual honesty and academic integrity; a case analysis scenario can include misleading or false information . A case study paper must report research objectively and factually to ensure that any findings are understood to be logically correct and trustworthy. A case analysis scenario may include misleading or false information intended to deliberately distract from the central issues of the case. The purpose is to teach students how to sort through conflicting or useless information in order to come up with the preferred solution. Any use of misleading or false information in academic research is considered unethical.

- Case study is linked to a research problem; case analysis is linked to a practical situation or scenario . In the social sciences, the subject of an investigation is most often framed as a problem that must be researched in order to generate new knowledge leading to a solution. Case analysis narratives are grounded in real life scenarios for the purpose of examining the realities of decision-making behavior and processes within organizational settings. A case analysis assignments include a problem or set of problems to be analyzed. However, the goal is centered around the act of identifying and evaluating courses of action leading to best possible outcomes.

- The purpose of a case study is to create new knowledge through research; the purpose of a case analysis is to teach new understanding . Case studies are a choice of methodological design intended to create new knowledge about resolving a research problem. A case analysis is a mode of teaching and learning intended to create new understanding and an awareness of uncertainty applied to practice through acts of critical thinking and reflection.

- A case study seeks to identify the best possible solution to a research problem; case analysis can have an indeterminate set of solutions or outcomes . Your role in studying a case is to discover the most logical, evidence-based ways to address a research problem. A case analysis assignment rarely has a single correct answer because one of the goals is to force students to confront the real life dynamics of uncertainly, ambiguity, and missing or conflicting information within professional practice. Under these conditions, a perfect outcome or solution almost never exists.

- Case study is unbounded and relies on gathering external information; case analysis is a self-contained subject of analysis . The scope of a case study chosen as a method of research is bounded. However, the researcher is free to gather whatever information and data is necessary to investigate its relevance to understanding the research problem. For a case analysis assignment, your professor will often ask you to examine solutions or recommended courses of action based solely on facts and information from the case.

- Case study can be a person, place, object, issue, event, condition, or phenomenon; a case analysis is a carefully constructed synopsis of events, situations, and behaviors . The research problem dictates the type of case being studied and, therefore, the design can encompass almost anything tangible as long as it fulfills the objective of generating new knowledge and understanding. A case analysis is in the form of a narrative containing descriptions of facts, situations, processes, rules, and behaviors within a particular setting and under a specific set of circumstances.

- Case study can represent an open-ended subject of inquiry; a case analysis is a narrative about something that has happened in the past . A case study is not restricted by time and can encompass an event or issue with no temporal limit or end. For example, the current war in Ukraine can be used as a case study of how medical personnel help civilians during a large military conflict, even though circumstances around this event are still evolving. A case analysis can be used to elicit critical thinking about current or future situations in practice, but the case itself is a narrative about something finite and that has taken place in the past.

- Multiple case studies can be used in a research study; case analysis involves examining a single scenario . Case study research can use two or more cases to examine a problem, often for the purpose of conducting a comparative investigation intended to discover hidden relationships, document emerging trends, or determine variations among different examples. A case analysis assignment typically describes a stand-alone, self-contained situation and any comparisons among cases are conducted during in-class discussions and/or student presentations.

The Case Analysis . Fred Meijer Center for Writing and Michigan Authors. Grand Valley State University; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Ramsey, V. J. and L. D. Dodge. "Case Analysis: A Structured Approach." Exchange: The Organizational Behavior Teaching Journal 6 (November 1981): 27-29; Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods . 6th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2017; Crowe, Sarah et al. “The Case Study Approach.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 11 (2011): doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-100; Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods . 4th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishing; 1994.

- << Previous: Reviewing Collected Works

- Next: Writing a Case Study >>

- Last Updated: May 7, 2024 9:45 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

Using IRAC – to solve problems & to read cases.

- 31 May 2021

- IRAC , Legal Writing , Research , Tips for Students

What is IRAC?

IRAC ( Issue , Rule , Analysis , and Conclusion ) forms the fundamental building blocks of legal analysis. It is the process by which lawyers think about any legal problem. The beauty of IRAC is that it allows you to reduce the complexities of the law to a simple equation.

- I SSUE: What facts and circumstances brought these parties to court?

- R ULE: What is the governing law for the issue?

- A NALYSIS: Does the rule apply to these unique facts?

- C ONCLUSION: How does the court’s holding modify the rule of law?

IRAC is a commonly recommended ‘tool’ for addressing legal problem tasks. It is a great tool for:

- Planning your responses to essay / problem questions;

- Writing answers to problem questions under pressure in an exam

- Organising your notes

- Checking that you’ve covered all bases when reviewing an assignment.

IRAC is not always the best way to structure your writing – particularly in a complex assignment . IRAC is great for planning responses, organising your thoughts and making notes when you read cases LawStudent.Solutions

Using IRAC (or (M)IRAC)

The following summarises the the process. You will note that we have included an additional step – identifying the material facts.

IRAC is also a helpful way to summarise cases. Keeping your notes in an IRAC format will help you index / sort them by issue. An example of a case analysis prepared using IRAC is set out below.

I – Identify the issues

It’s tempting to go straight to identifying the issues – but we always recommend starting issue spotting by identifying the most important – the material – facts.

Start with the material facts

Sorting through the facts you have been given to determine which facts are relevant and how you are going to use them is a necessary part of any problem solving task.

The following is a list of questions that may help you do this

- Who is involved? (identify parties specifically by name, if possible)

- Who suffered?

- Why? (was is avoidable?)

- What is the known (relevant) information?

- Is there any missing information?

- Include specific details like dates and monetary figures

Reread the question regularly. This will tell you what you are supposed to be doing and it will help you determine which facts are relevant LawStudent.Solutions

Issue spotting for problem solving

- Identify the problem: what has gone wrong and for whom?

- Name each Plaintiff and Defendant and briefly describe their individual issues

- Work out what area of law may govern the resolution of the problem.

- Be specific rather than general – if it’s a contract law question, specify what part. Assignments generally relate to one area of law but the assignment will usually raise a number of issues within that general area.

- Identify any conflicting or troublesome facts – which facts are important.

Issue spotting when reading a case

- What facts and circumstances brought these parties to court?

- Are there key words in the judgement / report that suggest an issue?

- Is the court deciding a question of fact ? – i.e. the parties are in dispute over what happened – or is it a question of law? – i.e. the court is unsure which rule to apply to these facts?

- What are the non-issues?

The trap for the unwary is to stop at the rule. Although the rule is the law, the art of lawyering is in the analysis. LawStudent.Solutions

R – Rule / Relevant Law

Rule spotting for problem solving.

- Set out the legal principles that will be used to address the problem.

- Source legal principles from cases and legislation – aim to have a citation for every rule.

- Treat a statement of law as a statement that requires support / verification – if you make a statement about what the law is, support it with a (correctly cited) case or section. Be specific – point to the specific section, paragraph or page of the judgement. Be judicious in your choice – pick the most relevant / applicable cases.

Make sure you are specific when stating the relevant law/rules that apply, and always make sure to support propositions with case authority LawStudent.Solutions

Rule spotting when reading a case

Simply put, the rule is the law . The rule could be common law that was developed by the courts or a law that was passed by the legislature.

When you’ve finished reading a case, ask yourself: “What does this case stand for?” Assume your lecturer is not a psychopath and they’ve assigned the reading for a reason! LawStudent.Solutions

For every case you read, extract the rule of law by breaking it down into its component parts. In other words, ask the question: what elements of the rule must be proven in order for the rule to hold true?Questions to ask when reading a case:

- What are the elements that prove the rule?

- What are the exceptions to the rule?

- From what authority does it come? Common law, statute, new rule?

- What’s the underlying public policy behind the rule?

- Are there social considerations?

A – Apply and analyse

“Compare the facts to the rule to form the Analysis.”

This important area is really relatively simple. For every relevant fact, you need to ask whether the fact helps to prove or disprove the rule. If a rule requires that a certain circumstance is present in order for the rule to apply, then the absence of that circumstance helps you reach the conclusion that the rule does not apply.

For instance, the successor legislation to the Statute of Frauds in each Australian jursidiction the effect of requiring that all contracts for the sale of land must be in writing. Consequently, in analyzing a problem involving an agreement for the sale of land, you apply the presence or absence of two facts – (a) the arrangement relates to land and (2) whether there’s a written contract – in order to see whether the rule holds true.

The biggest mistake people make in exam writing is to spot the issue and just recite the rule without doing the analysis . In open book exams (which is the case for most Australian Law exams) it’s a given that you can look up the law, so the real question is whether you can apply the law to a given set of circumstances. The analysis is the most important element of IRAC since this is where the real thinking happens.

Analysis for problem solving

- Explain in detail why the claims are (or are not) justified, based on the body of law pertaining to the case.

- Be clear on who you are advising and consider and explain how the law be used by each party to argue their case. It’s important to be able to explain what your client will need to counter.

- Use relevant precedent cases, Legal Principles and/or legislation to support each answer (you should have already identified these, but often you’ll find you’re moving backwards and forwards as you do your research).

- There may be several parties involved. Take the time to examine each case individually and analyse why their claims are (or are not) valid.

- Legal Principles and precedent cases should be used in each analysis, even if there is overlap between the parties (sometimes the same precedent will apply to more than one case, sometimes you will need to distinguish between the cases).

- It is acceptable to refer the reader to another point in the paper, rather than rewriting it word for word, if the situation calls for the same legal recommendation. (This is signposting)

Take time to discuss the contentious aspects of the case rather than the ones that are most comfortable or obvious LawStudent.Solutions

Analysis when reading a case

Questions to ask when reading a case:

- Which facts help prove which elements of the rule?

- Why are certain facts relevant?

- How do these facts satisfy this rule?

- What types of facts are applied to the rule?

- How do these facts further the public policy underlying this rule?

- What’s the counter-argument for another solution?

C – (Tentative) Conclusions

“From the analysis you come to a Conclusion as to whether the rule applies to the facts.”

The conclusion is the shortest part of the equation. It can be a simple “yes” or “no” as to whether the rule applies to a set of facts. Law exam and assignment problems will often include a set of facts/issues that could go either way in order to see how well you analyze a difficult case.

The mistake many students make is to never take a position one way or the other on an issue . Most examiners / assessors are looking to see how well you take a position and support it in order to see how well you analyze. LawStudent.Solutions

Another common mistake is to conclude something without having a basis for the opinion . In other words, students will spot the issue, state a rule, and then form a conclusion without doing the analysis. Make sure that whatever position you take has a firm grounding in the analysis. Remember that the position you take is always whether or not the rule applies.

If a rule does not apply, don’t fall into the trap of being conclusive on a party’s liability or innocence. There may be another rule by which the party should be judged. In other words you should conclude as to whether the rule applies, but you shouldn’t be conclusive as to whether some other result is probable. In that case, you need to raise another rule and analyze the facts again.

In addition, the conclusion should always be stated as a probable result. Courts differ widely on a given set of facts, and there is usually flexibility for different interpretations. Be sure to look at the validity of the opponent’s position. If your case has flaws, it is important to recognize those weaknesses and identify them.

Conclusions when problem solving

- Stand back and play ‘the judge.’

- Your client won’t always be the good guy – your job is to identify the correct answer, not to find ways to advocate for your client. If theirs is not a strong case, tell them!

- Choose the argument you think is the strongest and articulate what you believe to be the appropriate answer.

- State who is liable for what and to what extent.

- Consider how parties could have acted to better manage their risks in order to avoid this legal problem.

- Your conclusion should logically flow from the reasoning.

Your conclusion will almost always be a tentative conclusion – but at the same time, don’t sit on the fence. Give an indication of where you think the end result would go.

Conclusions when reading a case

Practical approaches for using irac.

The IRAC Triad emphasizes the Analysis by using the Facts , Issue and Rule as building blocks. The Analysis is the end product and primary goal of the IRAC Triad, but the role that facts play in forming the analysis is highlighted. The Triad is actually just a simple flowchart in which the facts can be pigeonholed into a Conclusion .

The facts of a case suggest an Issue . The legal issue would not exist unless some event occurred.

The issue is governed by a Rule of law. The issue mechanically determines what rule is applied.

Compare the facts to the rule to form the Analysis . Do the facts satisfy the requirements of the rule?

Example: using IRAC to make a case note:

Another popular legal problem solving method is referred to as MIRAT – and you might be able to see that the way I approach using IRAC is really a blend of IRAC and MIRAT. Read more about MIRAT in this article Meet MIRAT: Legal Reasoning Fragmented into Learnable chunks

Related Resources

Writing a legal memo (for an assignment)

- June 18, 2021

Online Research – looking for secondary materials

Online Research using Benchbooks

Insert/edit link.

Enter the destination URL

Or link to existing content

Identify The Problem: the first step to cracking a case study

- Identify the problem

- Build your Problem Driven Structure

- Lead the Analysis

- Provide recommendations

Four Steps to Identify the Problem

Common mistakes.

Correctly identifying the problem is the first step to successfully solving a case . This might seem obvious - surely one has to know what a question is in order to answer it correctly? However, failing the identify the problem derails far too many case interviews before they have even gotten started. Many otherwise-promising candidates lose out on jobs as they miss the whole point of the case .

In light of this, MyConsultingCoach has developed a structured, step-by-step approach to identifying the problem . This approach should make sure that you are addressing the correct question every time, giving you the best possible chance of cracking your case and impressing your interviewer.

Prep the right way

This article provides an outline of our method, which will get you started with identifying the problem in your case practice. In our MCC Academy , we have a comprehensive video lesson , which is the gold-standard resource for this topic . This goes through our method to identify the problem in greater detail than is possible here and includes more examples to help you get to grips with the material more quickly.

Case prompts can vary immensely. Some will be straightforward , with a clear and specific problem. For example:

"Our client, a supermarket, has seen a decline in profits. How can we bring them up?"

Often, though, you'll be given rather more open ended questions and/or questions asking about unfamiliar industries where you are unlikely to have much pre-existing knowledge.

For example:

"How much would you pay for a banking license in Ghana?"

Or, alternatively :

"What would be your key areas of concern when setting up an NGO?"

Whatever prompt you get, don't let it panic you. Remember, you aren't being assessed on your previous knowledge - nobody expects you to have read up on the Ghanaian banking system just in case it came up. Interviewers care less about what you happen to know than they do about your ability to ask smart questions . Difficult case prompts are a test in themselves and assess your abilities to prioritise, to cope with ambiguity, to learn quickly and to impose structure - all whilst managing your own stress.

Whether the prompt seems straightforward or difficult and ambiguous, you can apply the same method to make sure that you correctly identify the problem.

Join thousands of other candidates cracking cases like pros

From start to finish, we can break down the process into four key steps . This might all seem like quite a lot to remember on first reading. However, with a little practice, this method will soon become second nature and you will be able to correctly identify the problem for any given case in a few minutes.

1. Listen to the case prompt and take tidy notes

This might seem obvious, but paying attention and taking notes you can actually read to refer back to is crucial - not just for identifying the problem, but for your subsequent analysis as well. Don't make any assumptions straight off the bat - just jot down the facts.

2. Engage the interviewer and ask key questions

Now, it's time to respond to the interviewer. We can break this response down into two areas:

2a. Engage the interviewer

Your first words should engage your interviewer. By this, we mean that you should try to establish a rapport with your interviewer and to demonstrate your interest in the problem . It is important to show that you are enthusiastic and actually enjoy tackling tricky cases - after all, you are supposed to want to do it full time!

2b. Clarify unclear information in the prompt

After engaging the interviewer, it's time to ask some questions - not too many! It is important to ask questions sparingly and in a structured, thoughtful way, rather than just rattle off a dozen at once.

We cannot stress the importance of these questions enough. You must actually understand the prompt to have a chance of identifying the problem and you must identify the problem to solve the case. It will do you no good to make a mess of a whole case study because you didn't want to admit that you weren't sure of something at the start!

There are two kinds of question which you might need to ask:

- First, you might need to clarify relatively simple matters , such as the definitions of any terms you are not familiar with. Similarly, you might need to clarify the scope of the problem and the timeframe in which you are operating. For instance, it may be that the client company is on the edge of bankruptcy and will go bust within a couple of months if things can't be turned around - meaning you will be looking for solutions which will be effective in the immediate term!

- Second, you will need to ask some questions to get more detail about how the client company functions and the business environment it exists within. Precisely what you need to ask will very much depend on the specific case. For example, you might want to ask about the company's value chain or how its market share has been changing over time. Whichever questions you do ask, though, you should make sure to be specific and have a clear rationale for each.

3. Formulate your hypothesis on the problem

Now that you have gathered all the information you need, you should be able to form an hypothesis on what the problem actually is .

To formulate this hypothesis, ask yourself the key question:

What is the single, key, most important success criterion for the client?

You can test this hypothesis by asking yourself two follow up questions:

If this problem is solved, will it make the project successful? If it is not solved, will this problem jeopardize the project?

If your hypothesis meets both these conditions, it is probably the correct one and you can move on to validate it.

4. State the problem, get feedback and refine if necessary

The final step to identify the problem is to confirm that your hypothesis is correct . This is crucial - do not be tempted to just assume you are correct and skip ahead to the analysis without being sure. As we will see in the next section, mistakes are easy to make and must always be guarded against.

Here, you should briefly restate the problem to the interviewer in your own words. Be sure to take a top down approach (our articles on CEO level communication and the Pyramid Principle might be useful here) and to integrate what you have learnt from your questions to the interviewer. Don't just repeat the interviewer's own words back to them like a robot! Re-phrasing and integrating what you have been told show that you have been listening and that you understand what has been said.

Everything you need in one place

Ask the interviewer to validate your hypothesis - that is, to say if you have gotten the problem right. If they say you are correct, you can move on to start structuring the problem and begin your analysis . If not, you can adjust your hypothesis and try again, iterating until you arrive at the correct problem. This way, you will be sure you will always be sure you have successfully identified the problem before you go on to analyse it.

Candidates tend to fall into the same traps over and over again . Even with our step-by-step scheme to help you out, these can be easy mistakes to make and you should keep them in mind so as to avoid making costly errors. We can group these mistakes together into three categories:

Being too narrow

It is easy to identify too narrow a problem. This will mean that you address only a subset of the client's main issue. For example, you might focus only on growing a company's profitability in the short term, without giving sufficient consideration to how the company can grow in the medium to long term.

This kind of mistake can be avoided by being sure to ask your interviewer for clarification if there is any ambiguity in the scope of the case prompt (see 2b, above). You should also ask yourself whether an answer to the problem you have identified would really give the client a complete answer to their concerns.

Being too broad

It is also possible to be too broad. Identifying too broad a problem will lead you to try to understand too much and provide a very general analysis which will be largely irrelevant to the client's actual issue. This will make very inefficient use of your time and you will quite likely not reach a solution within the timeframe of the interview.

Just as with being too narrow, you can avoid too broad an approach by being sure to ask you interviewer questions about any ambiguity and by asking yourself whether the client will actually find this answer to the question you are identifying useful. Is what you are doing really necessary to address their key concern? Our article on taking a hypothesis driven approach to problems is also particularly useful here in making sure you keep your eye on the main problem and avoid unnecessary analysis.

Addressing the wrong problem

You might think that one would have to be some kind of idiot to end up tacking completely the wrong problem and that this won't happen to you. However, case prompts will often obscure the real problem. This might very well be intentional on the part of the interviewer as a way to test you (after all, interviewers in all industries will make use of trick questions ) It will require real thought and attention to make sure you don't embark down the wrong path. This can be the case for working consultants as well, as clients will often have a poor understanding of what is causing their company's issues and inadvertently attempt to push consultants in the wrong direction.

Forget outdated, framework-based guides...

Now that we have learnt how we should go about identifying the problem in principle, it's time to put these ideas into practice. Let's see how a case might be tackled incorrectly and how our step-by-step approach can help improve matters. As an example, let's say your interviewer gives you the following prompt:

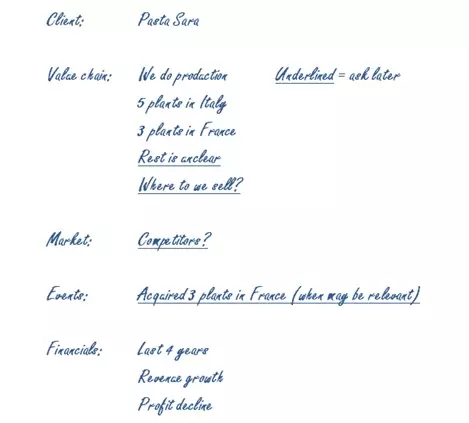

Our client, Pasta Sara, is a major producer of dried pasta. Pasta Sara is based in Italy and manages a network of 5 manufacturing plants, spread across the country. They have also acquired a company with 3 manufacturing plants in France. Pasta Sara has seen steady revenue growth but a slow, gradual decrease in profitability in the last 4 years. How can we help them?

Unsuccessful Candidate

We'll start with a candidate who does some things corectly, but who has also made some fatal mistakes. See if you can pick out what they get right and wrong:

Candidate: So the problem we’re trying to solve is to boost Pasta Sara’s profit margin. I’d like to ask a few clarifying questions before proceeding to structuring the problem. Is that ok? Interviewer: Go ahead Candidate: I’d like to know if this decrease in profitability was transversal to our operations or focused on a specific geographic area? This could probably help me identify specific issues there. Also, are there any trends I should be aware of in this industry? Additionally… Interviewer: Well regarding your first question… Candidate: Thank you for your answers. I’d like to take 30 seconds to structure my approach to this problem if that’s ok with you Interviewer: Go ahead

Okay, so what did the candidate do correctly? Well, they at least attempted (however unsuccessfully) to pinpoint the problem. They were also explicit about what they were doing and provided a rationale for their questions.

However, the candidate also made some serious errors. First, as regards engaging the interviewer, they didn't make an effort to show interest and establish a rapport. The candidate then jumped the gun by attempting to define the problem too early, before asking for any clarification or more information. They also didn't bother to check with the interviewer that they had identified the problem correctly.

Regarding the questions the candidate did ask, they barraged the interviewer with a whole list of queries. Not only were these questions too numerous, but they were also too vague; not being structured or targeted enough for the answers to actually be useful.

As a result of all this, the candidate totally missed the problem they were supposed to be solving . This means that (barring a miracle) their analysis will also fail to address the client's problem, so they will fail to solve their case and (barring another miracle) fail to get the job.

Successful Candidate

So, how can we improve on this unsuccessful candidate's performance? Let's see a more successful candidate apply our step-by-step process.

First, they listen carefully and make notes - which end up looking something like the following. These notes capture all the relevant information and our candidate has underlined pieces of information which they will need to ask about.

Now, our candidate replies to the interviewer:

“Thank you for the opportunity to look into this issue for our client. It sounds like an interesting case!” “To ensure I’m addressing the right issues and to familiarize myself with the problem, I would like to ask three brief questions” “First, could you let me know a bit more about our client’s business model? Which activities do they perform -is it only production, or do they also control distribution etc.? Second, I would like to understand who their main clients are and, third, I was wondering who their key competitors are and what their market share is? This would allow me to better tailor my approach to the problem”

Note that our candidate starts by engaging interviewer and expressing interest in the case. They make what they are doing explicit before asking a small number of questions aimed only at understanding the issue, rather than jumping straight into trying to solve the case. These questions are very structured and specific, so that the answers will be genuinely informative. They are also backed by a rationale explaining their relevance.

Looking for an all-inclusive, peace of mind program?

After the interviewer answers their questions, our candidate moves on to generate and test an hypothesis as to what the problem is.

Thank you for answering my questions. Before proceeding to addressing our client’s problem, I’d like to validate my understanding of that problem. Our client is a pasta manufacturer operating in Italy and France. The client has asked for our support because - despite strong revenue growth over the last few years - profits did not grow in line with revenues, resulting in a declining profitability ratio. Our client’s objective is to improve this profitability ratio. Is this correct? Is there any other objective we should consider?

After securing positive feedback from the interviewer, our client is ready to move on to creating a structure and analyzing the problem, safe in the knowledge that this is indeed the correct problem and thus that they are that bit closer to landing their dream consulting job.

By now, you should have a pretty good idea on how to go about identifying the problem. Remember that, for a truly comprehensive look at this issue, you should see our video lesson in the MCC Academy . This goes through the whole process of identifying the problem in more detail and with more examples than can be packed into this kind of article.

Once you feel you understand how to identify the problem, you should move on to learn how to build a priority driven structure for it and to begin your analysis . Remember that you should be practising your skills as you learn them and that you can do so using our free case bank , as well as with the problems included in MCC Academy . This kind of active learning makes it much faster to get to grips with all the material and get a head start on really impressing your interviewer!

Find out more in our case interview course

Ditch outdated guides and misleading frameworks and join the MCC Academy, the first comprehensive case interview course that teaches you how consultants approach case studies.

Discover our case interview coaching programmes

Discover our career advancement programme

Account not confirmed

35 problem-solving techniques and methods for solving complex problems

Design your next session with SessionLab

Join the 150,000+ facilitators using SessionLab.

Recommended Articles

A step-by-step guide to planning a workshop, how to create an unforgettable training session in 8 simple steps, 47 useful online tools for workshop planning and meeting facilitation.

All teams and organizations encounter challenges as they grow. There are problems that might occur for teams when it comes to miscommunication or resolving business-critical issues . You may face challenges around growth , design , user engagement, and even team culture and happiness. In short, problem-solving techniques should be part of every team’s skillset.

Problem-solving methods are primarily designed to help a group or team through a process of first identifying problems and challenges , ideating possible solutions , and then evaluating the most suitable .

Finding effective solutions to complex problems isn’t easy, but by using the right process and techniques, you can help your team be more efficient in the process.

So how do you develop strategies that are engaging, and empower your team to solve problems effectively?

In this blog post, we share a series of problem-solving tools you can use in your next workshop or team meeting. You’ll also find some tips for facilitating the process and how to enable others to solve complex problems.

Let’s get started!

How do you identify problems?

How do you identify the right solution.

- Tips for more effective problem-solving

Complete problem-solving methods

- Problem-solving techniques to identify and analyze problems

- Problem-solving techniques for developing solutions

Problem-solving warm-up activities

Closing activities for a problem-solving process.

Before you can move towards finding the right solution for a given problem, you first need to identify and define the problem you wish to solve.

Here, you want to clearly articulate what the problem is and allow your group to do the same. Remember that everyone in a group is likely to have differing perspectives and alignment is necessary in order to help the group move forward.

Identifying a problem accurately also requires that all members of a group are able to contribute their views in an open and safe manner. It can be scary for people to stand up and contribute, especially if the problems or challenges are emotive or personal in nature. Be sure to try and create a psychologically safe space for these kinds of discussions.

Remember that problem analysis and further discussion are also important. Not taking the time to fully analyze and discuss a challenge can result in the development of solutions that are not fit for purpose or do not address the underlying issue.

Successfully identifying and then analyzing a problem means facilitating a group through activities designed to help them clearly and honestly articulate their thoughts and produce usable insight.

With this data, you might then produce a problem statement that clearly describes the problem you wish to be addressed and also state the goal of any process you undertake to tackle this issue.

Finding solutions is the end goal of any process. Complex organizational challenges can only be solved with an appropriate solution but discovering them requires using the right problem-solving tool.

After you’ve explored a problem and discussed ideas, you need to help a team discuss and choose the right solution. Consensus tools and methods such as those below help a group explore possible solutions before then voting for the best. They’re a great way to tap into the collective intelligence of the group for great results!

Remember that the process is often iterative. Great problem solvers often roadtest a viable solution in a measured way to see what works too. While you might not get the right solution on your first try, the methods below help teams land on the most likely to succeed solution while also holding space for improvement.

Every effective problem solving process begins with an agenda . A well-structured workshop is one of the best methods for successfully guiding a group from exploring a problem to implementing a solution.

In SessionLab, it’s easy to go from an idea to a complete agenda . Start by dragging and dropping your core problem solving activities into place . Add timings, breaks and necessary materials before sharing your agenda with your colleagues.

The resulting agenda will be your guide to an effective and productive problem solving session that will also help you stay organized on the day!

Tips for more effective problem solving

Problem-solving activities are only one part of the puzzle. While a great method can help unlock your team’s ability to solve problems, without a thoughtful approach and strong facilitation the solutions may not be fit for purpose.

Let’s take a look at some problem-solving tips you can apply to any process to help it be a success!

Clearly define the problem

Jumping straight to solutions can be tempting, though without first clearly articulating a problem, the solution might not be the right one. Many of the problem-solving activities below include sections where the problem is explored and clearly defined before moving on.

This is a vital part of the problem-solving process and taking the time to fully define an issue can save time and effort later. A clear definition helps identify irrelevant information and it also ensures that your team sets off on the right track.

Don’t jump to conclusions

It’s easy for groups to exhibit cognitive bias or have preconceived ideas about both problems and potential solutions. Be sure to back up any problem statements or potential solutions with facts, research, and adequate forethought.

The best techniques ask participants to be methodical and challenge preconceived notions. Make sure you give the group enough time and space to collect relevant information and consider the problem in a new way. By approaching the process with a clear, rational mindset, you’ll often find that better solutions are more forthcoming.

Try different approaches

Problems come in all shapes and sizes and so too should the methods you use to solve them. If you find that one approach isn’t yielding results and your team isn’t finding different solutions, try mixing it up. You’ll be surprised at how using a new creative activity can unblock your team and generate great solutions.

Don’t take it personally

Depending on the nature of your team or organizational problems, it’s easy for conversations to get heated. While it’s good for participants to be engaged in the discussions, ensure that emotions don’t run too high and that blame isn’t thrown around while finding solutions.

You’re all in it together, and even if your team or area is seeing problems, that isn’t necessarily a disparagement of you personally. Using facilitation skills to manage group dynamics is one effective method of helping conversations be more constructive.

Get the right people in the room

Your problem-solving method is often only as effective as the group using it. Getting the right people on the job and managing the number of people present is important too!

If the group is too small, you may not get enough different perspectives to effectively solve a problem. If the group is too large, you can go round and round during the ideation stages.

Creating the right group makeup is also important in ensuring you have the necessary expertise and skillset to both identify and follow up on potential solutions. Carefully consider who to include at each stage to help ensure your problem-solving method is followed and positioned for success.

Document everything

The best solutions can take refinement, iteration, and reflection to come out. Get into a habit of documenting your process in order to keep all the learnings from the session and to allow ideas to mature and develop. Many of the methods below involve the creation of documents or shared resources. Be sure to keep and share these so everyone can benefit from the work done!

Bring a facilitator

Facilitation is all about making group processes easier. With a subject as potentially emotive and important as problem-solving, having an impartial third party in the form of a facilitator can make all the difference in finding great solutions and keeping the process moving. Consider bringing a facilitator to your problem-solving session to get better results and generate meaningful solutions!

Develop your problem-solving skills

It takes time and practice to be an effective problem solver. While some roles or participants might more naturally gravitate towards problem-solving, it can take development and planning to help everyone create better solutions.

You might develop a training program, run a problem-solving workshop or simply ask your team to practice using the techniques below. Check out our post on problem-solving skills to see how you and your group can develop the right mental process and be more resilient to issues too!

Design a great agenda

Workshops are a great format for solving problems. With the right approach, you can focus a group and help them find the solutions to their own problems. But designing a process can be time-consuming and finding the right activities can be difficult.

Check out our workshop planning guide to level-up your agenda design and start running more effective workshops. Need inspiration? Check out templates designed by expert facilitators to help you kickstart your process!

In this section, we’ll look at in-depth problem-solving methods that provide a complete end-to-end process for developing effective solutions. These will help guide your team from the discovery and definition of a problem through to delivering the right solution.

If you’re looking for an all-encompassing method or problem-solving model, these processes are a great place to start. They’ll ask your team to challenge preconceived ideas and adopt a mindset for solving problems more effectively.

- Six Thinking Hats

- Lightning Decision Jam

- Problem Definition Process

- Discovery & Action Dialogue

Design Sprint 2.0

- Open Space Technology

1. Six Thinking Hats

Individual approaches to solving a problem can be very different based on what team or role an individual holds. It can be easy for existing biases or perspectives to find their way into the mix, or for internal politics to direct a conversation.

Six Thinking Hats is a classic method for identifying the problems that need to be solved and enables your team to consider them from different angles, whether that is by focusing on facts and data, creative solutions, or by considering why a particular solution might not work.

Like all problem-solving frameworks, Six Thinking Hats is effective at helping teams remove roadblocks from a conversation or discussion and come to terms with all the aspects necessary to solve complex problems.

2. Lightning Decision Jam

Featured courtesy of Jonathan Courtney of AJ&Smart Berlin, Lightning Decision Jam is one of those strategies that should be in every facilitation toolbox. Exploring problems and finding solutions is often creative in nature, though as with any creative process, there is the potential to lose focus and get lost.

Unstructured discussions might get you there in the end, but it’s much more effective to use a method that creates a clear process and team focus.

In Lightning Decision Jam, participants are invited to begin by writing challenges, concerns, or mistakes on post-its without discussing them before then being invited by the moderator to present them to the group.

From there, the team vote on which problems to solve and are guided through steps that will allow them to reframe those problems, create solutions and then decide what to execute on.

By deciding the problems that need to be solved as a team before moving on, this group process is great for ensuring the whole team is aligned and can take ownership over the next stages.

Lightning Decision Jam (LDJ) #action #decision making #problem solving #issue analysis #innovation #design #remote-friendly The problem with anything that requires creative thinking is that it’s easy to get lost—lose focus and fall into the trap of having useless, open-ended, unstructured discussions. Here’s the most effective solution I’ve found: Replace all open, unstructured discussion with a clear process. What to use this exercise for: Anything which requires a group of people to make decisions, solve problems or discuss challenges. It’s always good to frame an LDJ session with a broad topic, here are some examples: The conversion flow of our checkout Our internal design process How we organise events Keeping up with our competition Improving sales flow

3. Problem Definition Process

While problems can be complex, the problem-solving methods you use to identify and solve those problems can often be simple in design.

By taking the time to truly identify and define a problem before asking the group to reframe the challenge as an opportunity, this method is a great way to enable change.

Begin by identifying a focus question and exploring the ways in which it manifests before splitting into five teams who will each consider the problem using a different method: escape, reversal, exaggeration, distortion or wishful. Teams develop a problem objective and create ideas in line with their method before then feeding them back to the group.

This method is great for enabling in-depth discussions while also creating space for finding creative solutions too!

Problem Definition #problem solving #idea generation #creativity #online #remote-friendly A problem solving technique to define a problem, challenge or opportunity and to generate ideas.

4. The 5 Whys

Sometimes, a group needs to go further with their strategies and analyze the root cause at the heart of organizational issues. An RCA or root cause analysis is the process of identifying what is at the heart of business problems or recurring challenges.

The 5 Whys is a simple and effective method of helping a group go find the root cause of any problem or challenge and conduct analysis that will deliver results.

By beginning with the creation of a problem statement and going through five stages to refine it, The 5 Whys provides everything you need to truly discover the cause of an issue.

The 5 Whys #hyperisland #innovation This simple and powerful method is useful for getting to the core of a problem or challenge. As the title suggests, the group defines a problems, then asks the question “why” five times, often using the resulting explanation as a starting point for creative problem solving.

5. World Cafe

World Cafe is a simple but powerful facilitation technique to help bigger groups to focus their energy and attention on solving complex problems.

World Cafe enables this approach by creating a relaxed atmosphere where participants are able to self-organize and explore topics relevant and important to them which are themed around a central problem-solving purpose. Create the right atmosphere by modeling your space after a cafe and after guiding the group through the method, let them take the lead!

Making problem-solving a part of your organization’s culture in the long term can be a difficult undertaking. More approachable formats like World Cafe can be especially effective in bringing people unfamiliar with workshops into the fold.

World Cafe #hyperisland #innovation #issue analysis World Café is a simple yet powerful method, originated by Juanita Brown, for enabling meaningful conversations driven completely by participants and the topics that are relevant and important to them. Facilitators create a cafe-style space and provide simple guidelines. Participants then self-organize and explore a set of relevant topics or questions for conversation.

6. Discovery & Action Dialogue (DAD)

One of the best approaches is to create a safe space for a group to share and discover practices and behaviors that can help them find their own solutions.

With DAD, you can help a group choose which problems they wish to solve and which approaches they will take to do so. It’s great at helping remove resistance to change and can help get buy-in at every level too!

This process of enabling frontline ownership is great in ensuring follow-through and is one of the methods you will want in your toolbox as a facilitator.

Discovery & Action Dialogue (DAD) #idea generation #liberating structures #action #issue analysis #remote-friendly DADs make it easy for a group or community to discover practices and behaviors that enable some individuals (without access to special resources and facing the same constraints) to find better solutions than their peers to common problems. These are called positive deviant (PD) behaviors and practices. DADs make it possible for people in the group, unit, or community to discover by themselves these PD practices. DADs also create favorable conditions for stimulating participants’ creativity in spaces where they can feel safe to invent new and more effective practices. Resistance to change evaporates as participants are unleashed to choose freely which practices they will adopt or try and which problems they will tackle. DADs make it possible to achieve frontline ownership of solutions.

7. Design Sprint 2.0