A Case Study Exploring Supervisee Experiences in Social Justice Supervision

Volume 12 - Issue 1

Clare Merlin-Knoblich, Jenna L. Taylor, Benjamin Newman

Social justice is a paramount concept in counseling and supervision, yet limited research exists examining this idea in practice. To fill this research gap, we conducted a qualitative case study exploring supervisee experiences in social justice supervision and identified three themes from the participants’ experiences: intersection of supervision experiences and external factors, feelings about social justice, and personal and professional growth. Two subthemes were also identified: increased understanding of privilege and increased understanding of clients. Given these findings, we present practical applications for supervisors to incorporate social justice into supervision.

Keywords: social justice, supervision, case study, personal growth, practical applications

Social justice is fundamental to the counseling profession, and, as such, scholars have called for an increase in social justice supervision (Ceballos et al., 2012; Chang et al., 2009; Collins et al., 2015; Dollarhide et al., 2018, 2021; Fickling et al., 2019; Glosoff & Durham, 2010). Although researchers have studied multicultural supervision in the counseling profession, to date, minimal research has been conducted on implementing social justice supervision in practice (Dollarhide et al., 2021; Fickling et al., 2019; Gentile et al., 2009; Glosoff & Durham, 2010). In this study, we sought to address this research gap with an exploration of master’s students’ experiences with social justice supervision.

Social Justice in Counseling Counseling leaders have developed standards that reflect the profession’s commitment to social justice principles (Chang et al., 2009; Dollarhide et al., 2021; Fickling et al., 2019; Glosoff & Durham, 2010). For instance, the American Counseling Association’s ACA Code of Ethics (2014) highlights the need for multicultural and diversity competence in six of its nine sections, including Section F, Supervision, Training, and Teaching. Additionally, in 2015, the ACA Governing Council endorsed the Multicultural and Social Justice Counseling Competencies (MSJCC), which provide a framework for counselors to use to implement multicultural and social justice competencies in practice (Fickling et al., 2019; Ratts et al., 2015). All of these standards reflect the importance of social justice in the counseling profession (Greene & Flasch, 2019).

Social Justice Supervision Although much of the counseling profession’s focus on social justice emphasizes counseling practice, social justice principles benefit supervisors, counselors, and clients when they are also incorporated into clinical supervision. In social justice supervision, supervisors address levels of change that can occur through one’s community using organized interventions, modeling social justice in action, and employing community collaboration (Chang et al., 2009; Dollarhide et al., 2021; Fickling et al., 2019). These strategies introduce an exploration of culture, power, and privilege to challenge oppressive and dehumanizing political, economic, and social systems (Dollarhide et al., 2021; Fickling et al., 2019; Garcia et al., 2009; Glosoff & Durham, 2010; Pester et al., 2020). Moreover, participating in social justice supervision can assist counselors in developing empathy for clients and conceptualizing them from a systemic perspective (Ceballos et al., 2012; Fickling et al., 2019; Kiselica & Robinson, 2001). When a supervisory alliance addresses cultural issues, oppression, and privilege, supervisees are better able to do the same with clients (Chang et al., 2009; Dollarhide et al., 2021; Fickling et al., 2019; Glosoff & Durham, 2010). Thus, counselors become advocates for clients and the profession (Chang et al., 2009; Dollarhide et al., 2021; Gentile et al., 2009; Glosoff & Durham, 2010).

Chang and colleagues (2009) defined social justice counseling as considering “the impact of oppression, privilege, and discrimination on the mental health of the individual with the goal of establishing equitable distribution of power and resources” (p. 22). In this way, social justice supervision considers the impact of oppression, privilege, and discrimination on the supervisee and supervisor. Dollarhide and colleagues (2021) further simplified the definition of social justice supervision, stating that it is “supervision in which social justice is practiced, modeled, coached, and used as a metric throughout supervision” (p. 104). Supervision that incorporates a focus on intersectionality can further support supervisees’ growth in developing social justice competencies (Greene & Flasch, 2019).

Literature about social justice supervision often includes an emphasis on two concepts: structural change and individual care (Gentile et al., 2009; Lewis et al., 2003; Toporek & Daniels, 2018). Structural change is the process of examining, understanding, and addressing systemic factors in clients’ and counselors’ lives, such as identity markers and systems within family, community, school, work, and elsewhere. Individual care acknowledges each person within the counseling setting independent of their environment (Gentile et al., 2009; Roffman, 2002). Scholars advise incorporating both concepts to address power, privilege, and systemic factors through social justice supervision (Chang et al., 2009; Gentile et al., 2009; Glosoff & Durham, 2010; Greene & Flasch, 2019; Pester et al., 2020).

It is necessary to distinguish social justice supervision from previous literature on multicultural supervision. Although similar, these concepts are different in that multicultural supervision emphasizes cultural awareness and competence, whereas social justice supervision brings attention to sociocultural and systemic factors and advocacy (Dollarhide et al., 2021; Fickling et al., 2019; E. Lee & Kealy, 2018; Peters, 2017; Ratts et al., 2015). For instance, a supervisor practicing multicultural supervision would be aware of a supervisee’s identity markers, such as race, ethnicity, and culture, and address those components throughout the supervisory experience, whereas a supervisor practicing social justice supervision would also consider systemic factors that impact a supervisee, in addition to being culturally competent. The supervisor would use that knowledge in the supervisory alliance and act as a change agent at individual and community levels (Chang et al., 2009; Dollarhide et al., 2021; Fickling et al., 2019; Gentile et al., 2009; Glosoff & Durham, 2010; E. Lee & Kealy, 2018; Lewis et al., 2003; Peters, 2017; Ratts et al., 2015; Toporek & Daniels, 2018).

Researchers have found that multicultural supervision contributes to more positive outcomes than supervision without consideration for multicultural factors (Chopra, 2013; Inman, 2006; Ladany et al., 2005). For example, supervisees who participated in multicultural supervision reported that supervisors were more likely to engage in multicultural dialogue, show genuine disclosure of personal culture, and demonstrate knowledge of multiculturalism than supervisors who did not consider multicultural concepts in supervision (Ancis & Ladany, 2001; Ancis & Marshall, 2010; Chopra, 2013). Supervisees also reported that multicultural considerations led them to feel more comfortable, increased their self-awareness, and spurred them on to discuss multiculturalism with clients (Ancis & Ladany, 2001; Ancis & Marshall, 2010). Although parallel research on social justice supervision is lacking, findings on multicultural supervision are a promising indicator of the potential of social justice supervision.

Models In recent years, scholars have called for social justice supervision models to integrate social justice into supervision (Baggerly, 2006; Ceballos et al., 2012; Chang et al., 2009; Collins et al., 2015; Glosoff & Durham, 2010; O’Connor, 2005). However, to date, only three formal models of social justice supervision have been published. Most recently, Dollarhide and colleagues (2021) recommended a social justice supervision model that can be used with any supervisory theory, developmental model, and process model. In this model, the MSJCC are integrated using four components. First, the intersectionality of identity constructs (i.e., gender, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, abilities, etc.) is identified as integral in the supervisory triad between supervisor, counselor, and client. Second, systemic perspectives of oppression and agency for each person in the supervisory triad are at the forefront. Third, supervision is transformed to facilitate the supervisee’s culturally informed counseling practices. Lastly, the supervisee and client experience validation and empowerment through the mutuality of influence and growth (Dollarhide et al., 2021).

Prior to Dollarhide and colleagues’ (2021) model for social justice supervision, Gentile and colleagues (2009) proposed a feminist ecological framework for social justice supervision. This model encouraged the understanding of a person at the individual level through interactions within the ecological system (Ballou et al., 2002; Gentile et al., 2009). The supervisor’s role is to model socially just thinking and behavior, create a climate of equality, and implement critical thinking about social justice (Gentile et al., 2009; Roffman, 2002).

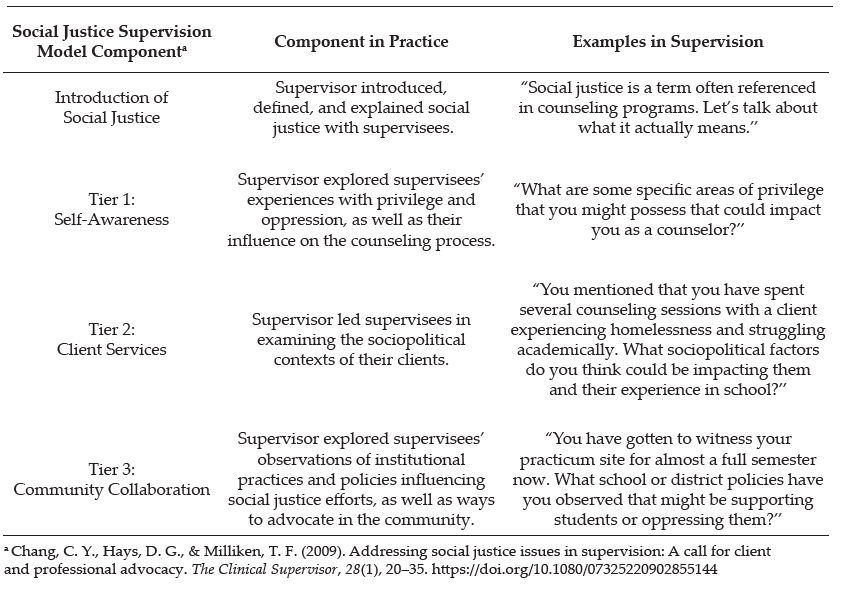

Lastly, Chang and colleagues (2009) suggested a social constructivist framework to incorporate social justice issues in supervision via three delineated tiers (Chang et al., 2009; Lewis et al., 2003; Toporek & Daniels, 2018). In the first tier, self-awareness , supervisors assist supervisees to recognize privileges, understand oppression, and gain commitment to social justice action (Chang et al., 2009; C. C. Lee, 2007). In the second tier, client services , the supervisor understands the clients’ worldviews and recognizes the role of sociopolitical factors that can impact the developmental, emotional, and cognitive meaning-making system of the client (Chang et al., 2009). In the third tier, community collaboration , the supervisor guides the supervisee to advocate for changes on the group, organizational, and institutional levels. Supervisors can facilitate and model community collaboration interventions, such as providing clients easier access to resources, participating in lobbying efforts, and developing programs in communities (Chang et al., 2009; Dinsmore et al., 2002; Kiselica & Robinson, 2001).

Each of these supervision models serves as a relevant, accessible tool for counseling supervisors to use to incorporate social justice into supervision (Chang et al., 2009, Dollarhide et al., 2021; Gentile et al., 2009). However, researchers lack an empirical examination of any of the models. To address this research gap and begin understanding social justice supervision in practice, the present qualitative case study exploring master’s students’ experiences with social justice supervision was undertaken.

We selected Chang and colleagues’ (2009) three-tier social constructivist framework in supervision for several reasons. First, the social constructivist framework incorporates a tiered approach similar to the MSJCC (Ratts et al., 2015) and reflects social justice goals in the profession of counseling (Ceballos et al., 2012; Chang et al., 2009; Collins et al., 2015; Glosoff & Durham, 2010). Second, the model is comprehensive. In using three tiers to address social justice (self, client, and community), the model captures multiple layers of social justice influence for counselors. Finally, the model is simple and meets the developmental needs of novice counselors. By identifying three tiers of social justice work, Chang and colleagues (2009) crafted an accessible tool to help new and practicing school counselors infuse social justice into their practice. This high level of structure matches the initial developmental levels of new counselors, who typically benefit from high amounts of structure and low amounts of challenge in supervision (Foster & McAdams, 1998).

The research question guiding this study was: What are the experiences of master’s counseling students in individual social justice supervision? We used a social constructivist theoretical framework and presumed that knowledge would be gained about the participants’ experiences based on their social constructs (Hays & Singh, 2012). The ontological perspective reflected realism, or the belief that constructs exist in the world even if they cannot be fully measured (Yin, 2017).

We selected a qualitative case study methodology because it was the most appropriate approach to explore the experiences of a single group of supervisees supervised by the same supervisor in the same semester. In this approach, researchers examine one identified unit bounded by space, time, and persons (Hancock et al., 2021; Hays & Singh, 2012; Yin, 2017). Qualitative case study research allows researchers to deeply explore a single case, such as a group, person, or experience, and gain an in-depth understanding of that identified situation, as well as meaning for the people involved in it (Hancock et al., 2021; Prosek & Gibson, 2021).

In this study, we selected a case study methodology because the study’s participants engaged in the same supervisory experience at the same counseling program in the same semester, thus forming a case to be studied (Hancock et al., 2021). Given the research question, we specifically used a descriptive case study design, which reflected the study goals to describe participants’ experiences in a specific social justice supervision experience. Case study scholars (Hancock et al., 2021; Yin, 2017) have noted that identifying the boundaries of a case is an essential step in the study process. Thus, the boundaries for this study were: master’s-level school counseling students receiving social justice supervision from the same supervisor (persons) at a medium-sized public university on the East Coast (place) over the course of a 14-week semester (time).

Research Team Our research team for this study consisted of our first and third authors, Clare Merlin-Knoblich and Benjamin Newman, both of whom received training and had experience in qualitative research. Merlin-Knoblich and Newman both identify as White, heterosexual, cisgender, middle-class, and trained counselor educators/supervisors. Merlin-Knoblich is a woman (pronouns: she/her/hers) and former school counselor, who completed master’s and doctoral coursework on social justice counseling and studied social justice supervision in a doctoral program. Newman is a man (pronouns: he/him/his) and clinical mental health/addictions counselor, who completed social justice counseling coursework in a master’s counseling program before completing a doctorate in counselor education and supervision. Our second author, Jenna L. Taylor, was not a part of the research team, but rather was a counseling student unaffiliated with the research participants who assisted in the preparation of the manuscript. Taylor identifies as a White, heterosexual, cisgender, and middle-class woman (pronouns: she/her/hers) with prior experience in research courses and on qualitative research teams. Merlin-Knoblich was familiar with all three participants given her role as the practicum supervisor. Taylor and Newman did not know the study participants beyond Newman’s interactions while recruiting and interviewing them for this study.

Participants and Context Although some scholars of some qualitative research methodologies call for requisite minimum numbers of participants, in case study research, there is no minimum number of participants sufficient to study (Hays & Singh, 2012). Rather, in case study research, researchers are expected to study the number of participants needed to reflect the phenomenon being studied (Hancock et al., 2021). There were three participants in this study because the supervisory experience that comprised the case studied included three supervisees. Adding additional participants outside of the case would have conflicted with the boundaries of the case and potentially interfered with an understanding of the single, designated case in this study.

All study participants identified as White, heterosexual, cisgender, middle-class, and English-speaking women (pronouns: she/her/hers). Participants were 23, 24, and 26 years old. All the participants were students in the same CACREP-accredited school counseling program at a public liberal arts university on the East Coast of the United States. Prior to the study, the participants completed courses in techniques, group counseling, school counseling, ethics, and theories. While being supervised, participants also completed a practicum experience and coursework in multicultural counseling and career development.

All participants completed practicum at high schools near their university. One high school was urban, one was suburban, and one was rural. During the practicum experience, participants met with Merlin-Knoblich, their supervisor, for face-to-face individual supervision for 1 hour each week. They also submitted weekly journals to Merlin-Knoblich, written either freely or in response to a prompt, depending on their preference. Merlin-Knoblich then provided weekly written feedback to each participant’s journal entry, and, if relevant, the journal content was discussed during face-to-face supervision. Simultaneously, a university faculty member provided weekly face-to-face supervision-of-supervision to Merlin-Knoblich to monitor supervision skills and ensure adherence to the identified supervision model. The faculty member possessed more than 15 years of experience in supervision and was familiar with social justice supervision models.

Merlin-Knoblich applied Chang and colleagues’ (2009) social constructivist social justice supervision model in deliberate ways throughout the supervisees’ 14-week practicum experience. For example, in the initial supervision sessions, Merlin-Knoblich introduced the supervision model and explained how they would collaboratively explore ideas of social justice in counseling related to their practicum experiences. This included defining social justice, discussing supervisees’ previous background knowledge, and exploring their openness to the idea.

Throughout the first 5 weeks of supervision, Merlin-Knoblich used exploratory questions to build participants’ self-awareness (the first tier), particularly around their experiences with privilege and oppression. During the next 5 weeks of supervision, Merlin-Knoblich focused on the second tier, understanding clients’ worldviews. They discussed sociopolitical factors and examined how a client’s worldview impacts their experiences. For example, Merlin-Knoblich discussed how a client’s age, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, family structure, language, immigrant status, gender identity, sexual orientation, and other factors can influence their experiences. Lastly, in the final 4 weeks of supervision, Merlin-Knoblich focused on the third tier of social justice implications at the institutional level. For instance, Merlin-Knoblich initiated discussions about policies at participants’ practicum sites that hindered equity. Merlin-Knoblich also explored the role that participants could take in making resources available to clients, advocating in the community, and using leadership to support social justice. Table 1 summarizes how Merlin-Knoblich implemented Chang and colleagues’ (2009) social justice model.

Merlin-Knoblich addressed fidelity to the supervision model in two ways. First, in weekly supervision-of-supervision meetings with the faculty advisor, they discussed the supervision model and its use in sessions with participants. The faculty advisor regularly asked about the supervision model and how it manifested in sessions in an attempt to ensure that the model was being implemented recurrently. Secondly, engagement with Newman occurred in regular peer debriefing discussions about the use of the supervision model. Through these discussions, Newman monitored Merlin-Knoblich’s use of the social justice model throughout the 14-week supervisory experience.

Data Collection We obtained IRB approval prior to initiating data collection. One month after the end of the semester and practicum supervision, Newman approached Merlin-Knoblich’s three supervisees about participation in the study. He explained that participation was an exploration of the supervisees’ experiences in supervision and not an evaluation of the supervisees or the supervisor. Newman also emphasized that participation in the study was confidential, entirely voluntary, and would not affect participants’ evaluations or grades in the practicum course, which ended before the study took place. All supervisees agreed to participate.

Case study research is “grounded in deep and varied sources of information” (Hancock et al., 2021) and thus often incorporates multiple data sources (Prosek & Gibson, 2021). In the present study, we identified two data sources to reflect the need for varied information sources (Hancock et al., 2021). The first data source came from semistructured interviews with participants, a frequent data collection tool in case study research (Hancock et al., 2021). One month after the participants’ practicum experiences ended, Newman conducted and audio-recorded 45-minute individual in-person interviews with each participant using a prescribed interview protocol that explored participants’ experiences in social justice supervision. Newman exercised flexibility and asked follow-up questions as needed (Merriam, 1998).

The interview protocol contained 12 questions identified to gain insights into the case being studied (Hancock et al., 2021). Merlin-Knoblich and Newman designed the interview protocol by drafting questions and reflecting on three influences: (a) the overall research question guiding the study, (b) the social constructivist framework of the study, and (c) Chang and colleagues’ (2009) three-tier supervision model. Questions included “In what ways, if any, has the social justice emphasis in your supervision last semester influenced you as a counselor?” Questions also addressed whether or not the emphasis on social justice at each tier (i.e., self, client, institution) affected participants. Appendix A contains a list of all interview questions.

The second data source was participants’ practicum journals. In addition to interviewing the participants about experiences in supervision, we also asked participants if their practicum journals could be used for the study’s data analysis. The journals served as a valuable form of data to answer the research question, given their informative and non-prescriptive nature. That is to say, although participants knew during the study interviews that the interview data would be used for analysis for the present study, they wrote and submitted their journals before the study was conceptualized. Thus, the journals reflected in-the-moment ideas about participants’ practicum and social justice supervision. Furthermore, this emphasis on participant experiences during the supervisory experience aligned with the methodological emphasis on studying a case in its natural context (Hancock et al., 2021). All participants consented for their 14 practicum journal entries (each 1–2 pages in length) to be analyzed in the study, and they were added to the interview data to be analyzed together. Such convergent analysis of data is typical in case study research (Prosek & Gibson, 2021).

Data Analysis We followed Yin’s (2017) case study research guidelines throughout the data analysis process. We transcribed all interviews, replaced participants’ names with pseudonyms, and sent participants the transcripts for member checking. Two participants approved their interview transcripts without objection. One participant approved the transcript but chose to share additional ideas about the supervisory experience via a brief email. This email was added to the data. The case study database was then formed with the compiled participants’ journal entries, the additional email, and the interview data (Yin, 2017).

Next, we read each interview transcript and journal entry twice in an attempt to become immersed in the data (Yin, 2017). We then independently open coded transcripts by identifying common words and phrases while maintaining a strong focus on the research question and codes that answered the question (Hancock et al., 2021). We compared initial codes and then collaboratively narrowed codes into cohesive categories representing participants’ experiences. This process generated a list of tentative categories across data sources (Yin, 2017). Throughout these initial processes, we attended to two of Yin’s (2017) four principles of high-quality data analysis: attend to all data and focus on the most significant elements of the case.

We then independently contrasted the tentative categories with the data to verify that they aligned accurately. We discussed the verifications until consensus was met on all categories. Lastly, we classified the categories into three themes and two subthemes found across all participants (Stake, 2005). During these later processes, we were mindful of Yin’s (2017) remaining two principles of high-quality data analysis: consider rival interpretations of data and use previous expertise when interpreting the case. Accordingly, we reflected on possible contrary explanations of the themes and considered the findings in light of previous literature on the topic.

Trustworthiness We addressed trustworthiness in three ways in this study. First, before data collection, we engaged in reflexivity through acknowledging personal biases and assumptions with one another (Hays & Singh, 2012; Yin, 2017). For example, Merlin-Knoblich acknowledged that her lived experience supervising the participants might impact the interpretation of data during analysis and noted that these perceptions could potentially serve as biases during the study. Merlin-Knoblich perceived that the supervisees grew in their understanding of social justice, but also acknowledged doubt over whether the social justice supervision model impacted participants’ advocacy skills. She also noted her role as a supervisor evaluating the three participants prior to the study taking place. These power dynamics may have influenced her interpretations in the analysis process. Newman shared that his lack of familiarity with social justice supervision might impact perceptions and biases to question whether or not supervisees grew in their understanding of social justice. We agreed to challenge one another’s potential biases during data analysis in an attempt to prevent one another’s experiences from interfering with interpretations of the findings.

In addition, we acknowledged that our identities as White, English-speaking, educated, heterosexual, cisgender, middle-class researchers studying social justice inevitably was informing personal perceptions of the supervisees’ experiences. These privileged identities were likely blinding us to experiences with oppression that participants and their clients encountered and that we are not burdened with facing. Throughout the study, we discussed the complexity of studying social justice in light of such privileged identities. We spoke further about our identities and potential biases when interpreting the data.

Second, investigator triangulation was addressed by collaboratively analyzing the study’s data (Hays & Singh, 2012). Because data included both interview transcripts and journals, we confirmed that study findings were reflected in both data sources, rather than just one information source (Hancock et al., 2021). This process helped prevent real or potential biases from informing the analysis without constraint. We also were mindful of saturation of themes while comparing data across participants and sources during the analysis process. Lastly, an audit trail was created to further address credibility. The study recruitment, data collection, and data analysis were documented so that the research can be replicated (Hays & Singh, 2012; Roulston, 2010).

In case study research, researchers use key quotes and descriptions from participants to illuminate the case studied (Hancock et al., 2021). As such, we next describe the themes and subthemes identified in study data using participants’ journal and interview quotes to illustrate the findings. Three overarching themes were identified in the data: 1) intersection of supervision experiences and external factors, 2) feelings about social justice, and 3) personal and professional growth. Two subthemes, 3a) increased understanding of privilege and 3b) increased understanding of clients, further expand the third theme.

Intersection of Supervision Experiences and External Factors One theme evident across the data was that participants’ experiences in social justice supervision did not occur in isolation from other experiences they encountered as counseling students. Coursework, overall program emphasis, and previous work experiences were external factors that created a compound influence on participants’ counselor development and intersected with their experiences of growth in supervision. Thus, external factors influenced participants’ understanding of and openness to a social justice framework. For example, concurrent with their practicum and supervision experiences, participants completed the course Theory and Practice of Multicultural Counseling. While discussing their experiences in supervision, all participants referenced this course. For example, Casey explained that exposure to social justice in the multicultural counseling course while discussing the topic in supervision made her more open and eager to learning about social justice overall.

Participants’ experiences prior to the counseling program also appeared to intersect with and influence their experiences in social justice supervision. Kallie, for instance, previously worked with African American and Latin American adolescents as a camp counselor at an urban Boys and Girls Club. She explained that social justice captured the essence of viewpoints formed in these experiences, saying, “I really like social justice because it kind of is like the title for the way I was looking at things already.” Casey grew up in California and reported that growing up on the West Coast also exposed her to a mindset parallel to social justice. Esther described that though she was not previously exposed to the term “social justice,” studying U.S., women’s, and African American history in college influenced her pursuit of a counseling career. This influence is evident in Esther’s third journal entry, in which she described noticing issues of power and oppression:

My own attention to an “arbitrarily awarded power” and personal questioning as to what to do with this consciousness has been at the forefront of my mind over the past two years. Ultimately this self-exploration led me to school counseling as a vehicle to advocate and raise consciousness in potentially disenfranchised groups.

This quote highlights how Esther’s previous studies in college may have primed her for the content she was exposed to in social justice supervision.

Feelings About Social Justice The second theme was a change in participants’ feelings toward social justice over the course of the semester. Two of the participants expressed that their feelings toward social justice changed from intimidation and fear to comfort and enthusiasm. Initially, Casey explained that social justice supervision created feelings of intimidation. Casey felt fear that the supervisor would instruct her to be an advocate at the practicum site, and that in doing so, Casey would upset others. However, Casey reported that she realized during supervision that social justice advocacy does not necessarily look one specific way. Casey said, “I think a lot of that intimidation went away as I realized that I could have my own style integrated into social justice.” Kallie expressed a similar pattern of emotions, particularly regarding examining clients from a social justice perspective. When asked to explore clients through this lens in supervision, an initial uncomfortable feeling emerged, but over the course of practicum, Kallie reported an attitude change. In the sixth journal entry, Kallie explained that she was focusing on examining all clients through a social justice lens, and “found it to be significantly easier this week than last week.”

Esther also shared evidence of changed emotions during social justice supervision. Initially, Esther reported feeling excited, but later, she was confused as to how counselors could use social justice practically. Despite this confusion, Esther shared that she gained new awareness that social justice advocacy is not only found in individual situations with clients, but also in an overall mindset:

Something I will take from it [supervision] . . . is you incorporate that sort of thinking into your overall [approach]. You don’t necessarily wait for a specific event to happen, but once you know the culture of a place, you have lessons geared towards whatever the problem is there.

Despite these mixed feelings, Esther’s experience aligns with Casey’s and Kallie’s, as all reported experiencing a change in emotions toward social justice over the course of supervision.

Personal and Professional Growth Participants also demonstrated changes in professional and personal growth throughout the supervision experiences, the third theme identified. In early journal entries, they reported nervousness, doubt, and insecurity regarding their counseling skills and knowledge. Over time, the tone shifted to increased comfort and confidence. This improvement appeared not only related to overall counseling abilities, but specifically to participants’ understanding of social justice in counseling. For example, in Esther’s second journal entry, she noted the influence that social justice supervision had on the ability to recognize oppression and bring awareness to it at practicum. Esther wrote, “Just having this concept be explicitly laid out in our plan has already caused me to be more attentive to such issues.”

Similarly, professional growth was evident in Kallie’s journal entries over time. In the fourth journal entry, Kallie described discomfort and nervousness when reflecting on clients’ sociopolitical contexts. However, in the ninth journal entry, Kallie described an experience in which she adapted her counseling to be more sensitive to the client’s multicultural background. Casey also highlighted growth with an anecdote about a small group she led. Casey explained that the group was for high-achieving, low-income juniors intending to go to college:

In the very beginning, I remember thinking—this sounds terrible now, but—“It’s kind of unfair to the other students that these kids get special privileges in that they get to meet with us and walk through the college planning process.” ’Cause I was thinking, “Wow, even kids who are high-achieving but are middle-class or upper-class, they could use this information, also. And it’s not really fair that just ’cause they’re lower class, they get their hand held during this.” But, throughout the semester, realizing that that’s not necessarily a bad thing for an institution to give another one a little extra help because they’re gonna have a deficit of help somewhere else in their life, and it really is fair. It’s more fair to give them more help ’cause they likely aren’t going to be getting it at home. . . . So, by having that group, it actually is making a greater degree of equity . . . through supervision and through processing all of that, [I learned] it was actually evening the board out more.

Participants also expressed that their professional growth in social justice competencies was intertwined with personal growth. Casey reported that supervision increased her comfort when talking about social justice issues and led to the reevaluation of personal opinions. Similarly, Kallie summarized:

I am very thankful that I had that social justice–infused model because it changed the way I think about people. . . . It kinda opened my eyes in a way I had not anticipated practicum opening my eyes. I didn’t expect that—social justice. I didn’t realize how big of an impact it would actually have.

Increased Understanding of Privilege Participants reported that understanding their privilege was one area of growth. During practicum, participants considered their areas of privilege and how these aligned or contrasted with those of clients. For example, in Esther’s third journal entry, she noted that interactions with clients made her more aware of personal privileges, which led her to create a list regarding gender identity, socioeconomic background, and sexual orientation. Casey and Kallie further described initially feeling resistant to the idea of White privilege. Casey explained:

I was a little resistant to the idea of White privilege originally, which I’ve since learned is a normal reaction. ’Cause I’ve kind of had the thought of “No! It’s America! All of us pull ourselves up by our bootstraps and everyone has the same opportunity,” which just isn’t the case. And so that definitely had a huge influence on me—realizing that I have huge privileges and powers that I did not, maybe didn’t want to, recognize before.

After initial resistance, participants reported that they transitioned from feeling shame about White privilege to an increased understanding and excitement to use privilege to create change.

Increased Understanding of Clients Lastly, participants also reported specific growth in their understanding of the clients whom they counseled. Participants believed they were better able to understand clients’ backgrounds and experiences because of social justice supervision. Kallie described how reflecting on clients’ sociopolitical contexts helped her better understand clients. She noted that the practice became a habit, saying, “It just kinda invaded the way I look at different people and see their backgrounds.” Casey also described an increased understanding of clients by sharing an example of a client who was highly intelligent, low-income, and Mexican American. Casey learned that the client intended to go to trade school to become a mechanic and was not previously exposed to other postsecondary education options like college. Casey described this realization as “a big moment” and said, “My interaction with him, for sure, was influenced by recognizing that there was social injustice there.”

The purpose of this study was to explore counseling students’ experiences in social justice supervision. Findings indicated that participants had meaningful experiences in social justice supervision that impacted them as future counselors. Topics of privilege, oppression, clients’ sociopolitical contexts, and advocacy were reportedly prominent in the participants’ supervision and influenced their experiences.

Despite many calls for social justice supervision in the counseling profession (Baggerly, 2006; Ceballos et al., 2012; Chang et al., 2009; Collins et al., 2015; Glosoff & Durham, 2010; O’Connor, 2005), this is the first known study about supervisees’ experiences with social justice supervision. It represents a new line of inquiry to understand what social justice supervision may be like for supervisees. Findings indicate that participants wrestled with understanding social justice and viewed it as a complex topic. They also suggest that participants found value in making sense of social justice and using it as a tool to better support clients individually and systemically. Similar to research on multicultural supervision, participants indicated that receiving social justice supervision was a positive experience and impacted personal and professional growth (Ancis & Ladany, 2001; Ancis & Marshall, 2010; Chopra, 2013; Inman, 2006; Ladany et al., 2005).

Notably, findings align with some, though not all, of Chang and colleagues’ (2009) delineated tiers in the social justice supervision model. Some of the themes reflect the first tier, self-awareness. For example, participants’ feelings about social justice (Theme 2) and increased understanding of privilege (Theme 3a) highlight how the supervisory experience enhanced their self-awareness as counselors. As their feelings changed and knowledge of privilege grew, their self-awareness improved, a critical task in becoming a social justice–minded counselor (Chang et al., 2009; Dollarhide et al., 2021; Fickling et al., 2019; Glosoff & Durham, 2010). Participants’ increased understanding of clients (Theme 3b) reflects the second tier in Chang and colleagues’ (2009) model, client services. In demonstrating an enhanced understanding of clients and their world experiences, the participants reported thinking beyond themselves and into how power, privilege, and oppression affected those they counseled.

The final tier of the social justice supervision model, community collaboration, was not evident in participant data about their experiences. Despite the supervisor’s intent to address this tier through analyses of school and district policies, as well as community advocacy opportunities, themes about this topic did not manifest in the data. This theme’s absence may suggest that the supervisor’s efforts to address the third tier were not strong enough to impact participants. Alternatively, the absence may suggest that participants were not developmentally prepared to make sense of social justice at a systemic, community level. Instead, their development matched best with social justice ideas at the self and client levels.

Participant findings did align with previous research about supervision. For example, Collins and colleagues (2015) studied master’s-level counseling students and found that their lack of experience in social justice supervision led them to feel unprepared to meet the needs of diverse clients. In this study, the presence of social justice supervision helped participants feel more prepared to support clients, as evidenced in the subtheme of increased understanding of clients . Furthermore, this study reflects similar findings from multicultural supervision research. We found that multicultural supervision was associated with positive outcomes of being prepared to work with diverse clients and engaging in effective supervision (Chopra, 2013; Inman, 2006; Ladany et al., 2005). This pattern is reflected in the current study, as participants reported positive experiences in social justice supervision. Ancis and Ladany (2001) and Ancis and Marshall (2010) found that incorporating multicultural considerations into supervision increases supervisees’ self-awareness and encourages them to engage clients in multicultural discussions. These same results were evident in the present study, with participants reporting personal and professional growth, such as stronger awareness of White privilege and greater willingness to examine clients’ sociopolitical contexts. Findings also reflect general research on supervision, which indicates that supervisees typically experience personal and professional growth in the process (Association for Counselor Education and Supervision, 2011; Watkins et al., 2015; Young et al., 2011).

Furthermore, study findings also align with assertions from supervision scholars regarding the value of social justice supervision. They support Chang and colleagues’ (2009) claim that social justice supervision can increase counselor self-awareness and build an understanding of oppression. Additionally, the findings also reflect Glosoff and Durham’s (2010) assertion that social justice in supervision helps supervisees gain awareness of power differentials. Finally, Ceballos and colleagues (2012) posited that social justice supervision will help counselors develop empathy for clients as counselors conceptualize clients in a systemic perspective. The participants’ enhanced understanding of White privilege and their clients’ contexts supports each of these ideas. Though findings are not generalizable, they appear to confirm scholars’ ideas about social justice supervision and suggest that the approach can be a positive, beneficial experience for counselors-in-training.

Limitations Study findings ought to be considered in light of the study’s limitations. First, although case study research focuses on a single identified case by definition and is not designed for generalization (Hays & Singh, 2012), the case in this study consisted of a demographically homogenous population of only three participants lacking racial, gender, and age diversity. This lack of diversity influenced participants’ experiences and study findings. Second, although the supervisor in this study did not conduct the semistructured interviews with participants in an attempt to prevent bias, participants were aware that Merlin-Knoblich was collaborating on the study, and this knowledge may have influenced their reported experiences. Merlin-Knoblich and Newman also began the study with acknowledged biases toward and against social justice supervision, and although they engaged in reflexivity and dialogue to prevent these biases from interfering with data analysis, there is no way to verify that this positionality did not influence the interpretation of findings. Lastly, our privileged identities served as a potential limitation while studying a topic like social justice supervision. Our racial, educational, class, language, and sexual identity privileges continually blind us to the experiences of oppression that others, including supervisees and clients, face. Seeking to know these perspectives better can increase our understanding of the implications of social injustices in society.

Implications for Counselor Educators and Supervisors The positive participant experiences illuminated through this study suggest that supervision based on this model may yield positive experiences for counselors-in-training, such as supporting students in developing self-awareness, understanding of clients’ sociopolitical contexts, and advocacy skills (Chang et al., 2009). Although the supervisor in this study used social justice supervision in individual sessions with participants, counselor educators may choose to apply social justice supervision models to group or triadic supervision. Counseling supervisors in agency, private practice, and school settings may also want to consider using social justice supervision to support counselors and subsequently clients (Baggerly, 2006; Ceballos et al., 2012; O’Connor, 2005). Furthermore, counselor educators teaching doctoral students may want to incorporate social justice supervision models into introductory supervision courses. Including these models into course content may in itself increase student interest in social justice (Swartz et al., 2018).

Regardless of the setting in which supervisors implement social justice supervision, the findings suggest practical implications that supervisors can consider. First, supervisors appear to benefit from considering social justice supervision models in their work (Chang et al., 2009; Dollarhide et al., 2021; Gentile et al., 2009). The findings in this study, plus previous research indicating positive outcomes for multicultural supervision (Chopra, 2013; Inman, 2006; Ladany et al., 2005), suggest that social justice supervision may potentially benefit counseling. Second, supervisors using social justice supervision may encounter supervisee confusion, discomfort, and/or enthusiasm when introduced to social justice supervision. These feelings also may change over the course of the supervisory relationship when learning about social justice. Third, supervisors ought to be mindful of all three tiers of Chang and colleagues’ (2009) social justice supervision model and a supervisee’s developmental match with each tier. As seen in this study, supervisees may be best matched for the first and second tiers of the model (self-awareness and client services), but not the third tier (community collaboration). Supervisors would benefit from assessing a supervisee’s potential for understanding community collaboration before deciding to infuse its focus in supervision.

More research is needed to understand social justice supervision. A variety of future studies, including different models, methods, and settings, would benefit the counseling profession. For example, a study implementing the social justice supervision model proposed by Dollarhide and colleagues (2021) can add to the needed research in this field. Additional qualitative studies with diverse supervisees in different counseling settings would be helpful in understanding if the experiences participants reported encountering in this study are common in social justice supervision. Quantitative studies on social justice supervision interventions would also add to the profession’s knowledge on the value of social justice supervision. Lastly, studies on supervisees’ experiences in social justice supervision compared to other models would highlight benefits and drawbacks of multiple supervision models (Baggerly, 2006; Chang et al., 2009; Glosoff & Durham, 2010).

In this article, we explored master’s-level counseling students’ experiences in social justice supervision via a qualitative case study. Through this exploration, we identified three themes reflecting participants’ experiences in social justice supervision: intersection of supervision experiences and external factors, feelings about social justice, and personal and professional growth, as well as two subthemes: increased understanding of privilege and increased understanding of clients. Findings suggest that social justice supervision may be a beneficial practice for supervisors and counselor educators to consider integrating in their work (Chang et al., 2009; Dollarhide et al., 2021; Gentile et al., 2009; Pester et al., 2020). Further research across contexts and with a range of methodologies is needed to better understand social justice supervision in practice.

Conflict of Interest and Funding Disclosure The authors reported no conflict of interest or funding contributions for the development of this manuscript.

American Counseling Association. (2014). ACA code of ethics . https://www.counseling.org/resources/aca-code-of-ethics.pdf

Ancis, J. R., & Ladany, N. (2001). A multicultural framework for counselor supervision. In L. J. Bradley & N. Ladany (Eds.), Counselor supervision: Principles, process, and practice (3rd ed., pp. 63–90). Brunner-Routledge.

Ancis, J. R., & Marshall, D. S. (2010). Using a multicultural framework to assess supervisees’ perceptions of culturally competent supervision. Journal of Counseling & Development , 88 (3), 277–284. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00023.x

Association for Counselor Education and Supervision. (2011). Best practices in clinical supervision . https://acesonline.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/ACES-Best-Practices-in-Clinical-Supervision-2011.pdf

Baggerly, J. (2006). Service learning with children affected by poverty: Facilitating multicultural competence in counseling education students. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development , 34 (4), 244–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1912.2006.tb00043.x

Ballou, M., Matsumoto, A., & Wagner, M. (2002). Toward a feminist ecological theory of human nature: Theory building in response to real-world dynamics. In M. Ballou & L. S. Brown (Eds.), Rethinking mental health and disorder: Feminist perspectives (pp. 99–141). Guilford.

Ceballos, P. L., Parikh, S., & Post, P. B. (2012). Examining social justice attitudes among play therapists: Implications for multicultural supervision and training. International Journal of Play Therapy , 21 (4), 232–243. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028540

Chang, C. Y., Hays, D. G., & Milliken, T. F. (2009). Addressing social justice issues in supervision: A call for client and professional advocacy. The Clinical Supervisor , 28 (1), 20–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/07325220902855144

Chopra, T. (2013). All supervision is multicultural: A review of literature on the need for multicultural supervision in counseling. Psychological Studies , 58 , 335–338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-013-0206-x

Collins, S., Arthur, N., Brown, C., & Kennedy, B. (2015). Student perspectives: Graduate education facilitation of multicultural counseling and social justice competency. Training and Education in Professional Psychology , 9 (2), 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1037/tep0000070

Dinsmore, J. A., Chapman, A., & McCollum, V. J. C. (2002). Client advocacy and social justice: Strategies for developing trainee competence . Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the American Counseling Association, Washington, DC.

Dollarhide, C. T., Hale, S. C., & Stone-Sabali, S. (2021). A new model for social justice supervision. Journal of Counseling & Development , 99 (1), 104–113. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12358

Dollarhide, C. T., Mayes, R. D., Dogan, S., Aras, Y., Edwards, K., Oehrtman, J. P., & Clevenger, A. (2018). Social justice and resilience for African American male counselor educators: A phenomenological study. Counselor Education and Supervision , 57 (1), 2–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12090

Fickling, M. J., Tangen, J. L., Graden, M. W., & Grays, D. (2019). Multicultural and social justice competence in clinical supervision. Counselor Education and Supervision , 58 (4), 309–316. https://doi.org/10.1002.ceas.12159

Foster, V. A., & McAdams, C. R., III. (1998). Supervising the child care counselor: A cognitive developmental model. Child and Youth Care Forum , 27 (1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02589525

Garcia, M., Kosutic, I., McDowell, T., & Anderson, S. A. (2009). Raising critical consciousness in family therapy supervision. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy , 21 (1), 18–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952830802683673

Gentile, L., Ballou, M., Roffman, E., & Ritchie, J. (2009). Supervision for social change: A feminist ecological perspective. Women & Therapy , 33 (1–2), 140–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/02703140903404929

Glosoff, H. L., & Durham, J. C. (2010). Using supervision to prepare social justice counseling advocates. Counselor Education and Supervision , 50 (2), 116–129. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2010.tb00113.x

Greene, J. H., & Flasch, P. S. (2019). Integrating intersectionality into clinical supervision: A developmental model addressing broader definitions of multicultural competence. The Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision , 12 (4). https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/jcps/vol12/iss4/14

Hancock, D. R., Algozzine, B., & Lim, J. H. (2021). Doing case study research: A practical guide for beginning researchers (4th ed.). Teachers College Press.

Hays, D. G., & Singh, A. A. (2012). Qualitative inquiry in clinical and educational settings . Guilford.

Inman, A. G. (2006). Supervisor multicultural competence and its relation to supervisory process and outcome. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy , 32 (1), 73–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2006.tb01589.x

Kiselica, M. S., & Robinson, M. (2001). Bringing advocacy counseling to life: The history, issues, and human dramas of social justice work in counseling. Journal of Counseling & Development , 79 (4), 387–397. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2001.tb01985.x

Ladany, N., Friedlander, M. L., & Nelson, M. L. (2005). Critical events in psychotherapy supervision: An interpersonal approach . American Psychological Association.

Lee, C. C. (2007). Counseling for social justice (2nd ed.). American Counseling Association.

Lee, E., & Kealy, D. (2018). Developing a working model of cross-cultural supervision: A competence- and alliance-based framework. Clinical Social Work Journal , 46 , 310–320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-018-0683-4

Lewis, J. A., Arnold, M. S., House, R., & Toporek, R. L. (2003). Advocacy competencies. www.counseling.org/resources/competencies/advocacy_competencies.pdf

Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. Jossey-Bass.

O’Connor, K. (2005). Assessing diversity issues in play therapy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice , 36 (5), 566–573. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.36.5.566

Pester, D. A., Lenz, A. S., & Watson, J. C. (2020). The development and evaluation of the Intersectional Privilege Screening Inventory for use with counselors-in-training. Counselor Education and Supervision , 59 (2), 112–128. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12170

Peters, H. C. (2017). Multicultural complexity: An intersectional lens for clinical supervision. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling , 39 , 176–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-017-9290-2

Prosek, E. A., & Gibson, D. M. (2021). Promoting rigorous research by examining lived experiences: A review of four qualitative traditions. Journal of Counseling & Development , 99 (2), 167–177. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12364

Ratts, M. J., Singh, A. A., Nassar-McMillan, S., Butler, S. K., & McCullough, J. R. (2015). Multicultural and social justice counseling competencies . www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/competencies/multicultural-and-social-justice-counseling-competencies.pdf

Roffman, E. (2002). Just supervision . Multicultural Perspectives on Social Justice and Clinical Supervision Conference, Cambridge, MA, United States.

Roulston, K. (2010). Reflective interviewing: A guide to theory and practice . SAGE.

Stake, R. E. (2005). Qualitative case studies. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp. 433–466). SAGE.

Swartz, M. R., Limberg, D., & Gold, J. (2018). How exemplar counselor advocates develop social justice interest: A qualitative investigation. Counselor Education and Supervision , 57 (1), 18–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceas.12091

Toporek, R. L., & Daniels, J. (2018). ACA advocacy competencies . https://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source /competencies/aca-advocacy-competencies-updated-may-2020.pdf?sfvrsn=f410212c_4

Watkins, C. E., Jr., Budge, S. L., & Callahan, J. L. (2015). Common and specific factors converging in psychotherapy supervision: A supervisory extrapolation of the Wampold/Budge Psychotherapy Relationship Model. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration , 25 (3), 214–235. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0039561

Yin, R. K. (2017). Case study research and applications: Designs and methods (6th ed.). SAGE.

Young, T. L., Lambie, G. W., Hutchinson, T., & Thurston-Dyer, J. (2011). The integration of reflectivity in developmental supervision: Implications for clinical supervisors. The Clinical Supervisor , 30 (1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2011.532019

Semistructured Interview Questions

- What brought you to this counseling program?

- Where did you complete your practicum?

- How would you describe the population you worked with at your practicum?

- What previous experience, if any, did you have with social justice prior to individual practicum supervision?

- During individual practicum supervision on campus last semester, what were some of your initial thoughts and feelings about a social justice–infused supervision model?

- In what ways, if any, did those thoughts and feelings about social justice change throughout your supervision experience?

These next three questions address three areas of social justice that were incorporated into your individual practicum supervision model: self, students (clients), and institution (school or school districts).

6. Do you think that the emphasis on social justice related to self (i.e., your power, privileges, and experience with oppression) in individual practicum supervision on campus had any influence on you?

- If yes, what influence did this emphasis have on you?

- If no, why do you think that’s the case?

7. Do you think that the emphasis on social justice related to others (i.e., the sociopolitical context of students, staff, etc.) in individual practicum supervision on campus had any influence on you?

8. Do you think that the emphasis on social justice related to institution (i.e., your practicum site, school district) in individual practicum supervision on campus had any influence on you?

- In what ways, if any, has the social justice emphasis in your individual practicum supervision influenced you as a counselor?

- In what ways, if any, has the social justice emphasis in your individual practicum supervision influenced your development as a person?

- How would you define social justice?

- Is there anything else you would like to add regarding your experience in a social justice–infused model of supervision last semester?

- Is there anything else you’d like to share?

Clare Merlin-Knoblich , PhD, NCC, is an associate professor at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. Jenna L. Taylor, MA, NCC, LPC-A, is a doctoral student at the University of North Texas. Benjamin Newman, PhD, MAC, ACS, LPC, CSAC, CSOTP, is a professional counselor at Artisan Counseling in Newport News, VA. Correspondence may be addressed to Clare Merlin-Knoblich, 9201 University City Blvd., Charlotte, NC 28211, [email protected].

Recent Publications

- Bridging the Gap: From Awareness to Action Introduction to the Special Issue March 18, 2024

- “A Learning Curve”: Counselors’ Experiences Working With Sex Trafficking January 17, 2024

- Ableist Microaggressions, Disability Characteristics, and Nondominant Identities January 17, 2024

- Using the Cultural Formulation Interview With Afro Latinx Immigrants in Counseling: A Practical Application January 17, 2024

Reflecting Through Counselling Supervision

Such preparation includes the asking of such questions as: I f I could risk telling my supervisor what really concerns me in my counselling work, what would that be?, What is my particular difficulty or problem in working with this client?, Is there anything I want to celebrate or feed back to my supervisor? (Page, Wosket, 1994) . Exploration of the work undertaken with clients enables the counsellor to explore their practice, identify their strengths, weaknesses, personal blocks, skills deficits and areas of expertise.

Apart from discussing the work the supervisee is undertaking the supervisor may use a variety of techniques to help the supervisee reflect upon their work. For example, listening to tapes of client work so that interventions can be evaluated at the micro-skills level, using adaptations of the IPR method mentioned above, asking the supervisee to ‘role-play’ particular situations that they may be finding difficult.

Some counselling supervisors encourage their supervisees to write a case study as part of on-going professional development (Parker, 1995) . Writing a case study provides the counsellor with an opportunity to view their work in a more formal way focusing on aspects of the work the counsellor found difficult, what learning took place, the counsellor’s internal world and what skills expertise or deficit were highlighted. The use of case-series studies may also be employed. Here, the counsellor combines into one case study several clients with common clinically relevant features. For example, a counsellor may wish to consider their approach to working with clients who share the characteristics of excessive or unhealthy emotional dependency, resistence or anger.

Previous posts in this series:

Reflective Practice and Self-Evaluation Keeping a Professional Development Log

Next in the series:

Monitoring Effectiveness

References:

Carroll, M (1996), Counselling Supervision – Theory, Skills and Practice, London: Cassell Feltham, C, Dryden, W (1994), Developing Counsellor Supervision, Dryden, W (ed) Developing Counselling Series, London: Sage Page, S, Wosket, V (1994) Supervising The Counsellor – a cyclical model, London: Routledge Parker, M (1995) ‘Practical Approaches : Case Study Writing’ in Counselling, p19-21, Volume 6, No 1, Rugby: British Association for Counselling.

Leave a reply Cancel reply

Bad Behavior has blocked 3701 access attempts in the last 7 days.

The impact of clinical supervision on counsellors and therapists, their practice and their clients A systematic review of the literature

Sue Wheeler and Kay Richards

BACP commissioned a systematic review to locate, appraise and synthesise evidence from research studies to obtain a reliable overview of the impact of clinical supervision.

This paper reports on the findings from articles published in this area since 1980, and reviews 25 individual published studies. The quality of evidence is variable, but supervision is consistently demonstrated to have some positive impacts on the supervisee.

The systematic review found limited evidence that:

- supervision can enhance the self-efficacy of the supervisee

- supervision has a beneficial effect on the supervisees, the client and the outcome of therapy

- supervision that focuses on the working alliance can influence client perception and enhance outcome in the treatment of depression

- clients treated by supervised therapists are more satisfied than those treated by unsupervised therapists

- skill and process supervision have the same positive impact on client outcome

- counselling and psychotherapeutic skills develop through supervision

Supervision

Information and resources for practitioners and supervisors

Supervision resources

Videos, FAQs and resources to support members in working with this section of the Ethical Framework for the Counselling Professions

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 22 August 2019

Empirical research in clinical supervision: a systematic review and suggestions for future studies

- Franziska Kühne ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9636-5247 1 ,

- Jana Maas 1 ,

- Sophia Wiesenthal 1 &

- Florian Weck 1

BMC Psychology volume 7 , Article number: 54 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

21k Accesses

36 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Although clinical supervision is considered to be a major component of the development and maintenance of psychotherapeutic competencies, and despite an increase in supervision research, the empirical evidence on the topic remains sparse.

Because most previous reviews lack methodological rigor, we aimed to review the status and quality of the empirical literature on clinical supervision, and to provide suggestions for future research. MEDLINE, PsycInfo and the Web of Science Core Collection were searched and the review was conducted according to current guidelines. From the review results, we derived suggestions for future research on clinical supervision.

The systematic literature search identified 19 publications from 15 empirical studies. Taking into account the review results, the following suggestions for further research emerged: Supervision research would benefit from proper descriptions of how studies are conducted according to current guidelines, more methodologically rigorous empirical studies, the investigation of active supervision interventions, from taking diverse outcome domains into account, and from investigating supervision from a meta-theoretical perspective.

Conclusions

In all, the systematic review supported the notion that supervision research often lags behind psychotherapy research in general. Still, the results offer detailed starting points for further supervision research.

Trial registration

PROSPERO; CRD42017072606 , registered on June 20, 2017.

Peer Review reports

Although in psychotherapy training and in profession-long learning, clinical supervision is regarded as one of the major components for change in psychotherapeutic competencies and expertise, its evidence base is still considered weak [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. Clinical supervision is currently considered a distinct competency in need of professional training and systematic evaluation; however, theoretical developments and experience-driven practice still seem to diverge, and “significant gaps in the research base” are evident ([ 1 ], p. 88).

Definitions of supervision underline different aspects, whereas a lack of consensus seems to impede research [ 1 ]. Falender and Shafranske [ 4 , 5 ] stress the development of testable psychotherapeutic competencies in the learners, i.e., their knowledge, skills and values/attitudes, through supervision; on the other hand, supervisors need to develop competence to deliver supervision. Milne and Watkins [ 6 ] describe clinical supervision as “the formal provision, by approved supervisors, of a relationship-based education and training that is work-focused and which manages, supports, develops and evaluates the work of colleague/s” (p. 4). In contrast, Bernard and Goodyear [ 7 ] emphasize supervision’s hierarchical approach, in as much as it is provided by more senior to more junior members of a profession. The goals of supervision may thus range between the poles of being normative (i.e., ensuring quality and case management), restorative (i.e., providing emotional and coping support) and formative (i.e., promoting therapeutic competence), and, thus, may ultimately lead to effective and safe psychotherapy [ 6 ]. Hence, it is pivotal for supervisors to reflect upon their own knowledge or skills gaps, and to engage in further qualification [ 8 ]. Clinical supervision may involve different therapeutic approaches and thus addresses therapists from varying mental health backgrounds [ 8 ], which is the stance taken in the current review.

Besides providing a definition of clinical supervision, it is relevant to delineate related terms. One is feedback , a supervision technique that “refers to the ‘timely and specific’ process of explicitly communicating information about performance” ([ 8 ], p. 28). Contrary to supervision, coaching strives to enhance well-being and performance in personal and work domains [ 9 ], and is therefore clearly distinct from supervision and psychotherapy with mental health patients provided by licensed therapists.

In the supervision literature, there is no paucity of narrative reviews, commentaries or concept papers. Previous reviews have revealed positive effects of supervision, for example on supervisee’s satisfaction, autonomy, awareness or self-efficacy [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ]. Still, results on the impact of supervision on patient outcomes are still considered mixed [ 10 ]. Importantly, there is a knowledge gap regarding the active components of supervision, i.e., the effects of supervision or supervisor interventions on supervisees and their patients [ 10 ].

Past reviews, however, suffer from several limitations (for details, see [ 14 ]). First of all, strategies used for literature search and screening have not always been described or implemented rigorously, that is, implemented in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA [ 15 ]) reporting guidelines (e.g. [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 ]). Further, several reviews focus specifically on the positive effects of supervision [ 19 ] or specifically on learning disabilities [ 11 ], emphasize the authors’ point of view [ 20 , 21 ], or concentrate on the supervisory relationship only [ 14 ]. While the majority of the above-mentioned reviews are narrative, Alfonsson and colleagues conducted a systematic review [ 14 ], pre-registered and published a review protocol [ 22 ] and implemented a thorough literature search and methodological appraisal. However, since they focused exclusively on cognitive behavioral supervision and on experimental designs, only five studies fit their inclusion criteria. Additionally, interrater agreement was only moderate during screening. Likewise, in our previous scoping review [ 23 ], we concentrated on cognitive behavioral supervision. Furthermore, like other supervision reviews [ 20 , 21 ], it was published in German only, limiting its scope.

Thus, the current systematic review aimed to complement previous reviews by using a comprehensive methodology and concise reporting. First, we aimed to review the current status of supervision interventions (e.g., setting, session frequency, therapeutic background) and of the methodological quality of the empirical literature on clinical supervision. Second, we aimed to provide suggestions for future supervision research.

Materials and methods

We conducted a systematic review by referring to the PRISMA reporting guidelines [ 15 ]. The review protocol was registered and published with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; CRD42017072606).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included studies referring to clinical supervision as defined above by Milne and Watkins [ 6 ] above. Both, supervision conducted on its own or as part of a larger intervention (as in psychotherapy training) were included. Treatment studies in which supervision was conducted solely to foster treatment delivery were excluded because they mainly address study adherence and are still covered in other reviews [ 24 , 25 ]. Furthermore, clinical supervision had to refer to psychotherapy, whereas supportive interventions accompanying other treatments (e.g., clinical management) were excluded. Thus, we included studies referring to mental health patients, and studies with patients with physical diseases were considered only if the reason for treatment was patients’ mental health. Studies with another population (e.g., simulated patients or pseudo-clients) were excluded. In order to focus the review in the heterogeneous field of clinical supervision, we limited it to adult patients. Studies on family therapy were included if they focused on adults. Studies with mixed adult and child/adolescent populations were included if the results were reported for the adult population separately. No prerequisites were predefined for supervisor qualification. Any empirical study published within a peer-reviewed process (i.e., without commentaries or reviews) and any outcome measures were included. As such, any supervision outcome (e.g., supervisees’ satisfaction or competence), including negative or unexpected outcomes (e.g., non-disclosure), were allowed. In line with Hill & Knox [ 10 ], we did not focus on studies exclusively examining the supervision process because firstly, it does not provide knowledge on the effectiveness of supervision, and secondly, relationship variables are already covered by other reviews [ 11 ]. Thus, the review focused on supervision interventions, and studies exclusively focusing on the effects of relationship variables or attitudes between the supervisee and supervisor (i.e., as independent variables) were excluded. However, relationship variables were considered if they were considered as dependent variables in the primary studies.

Study search

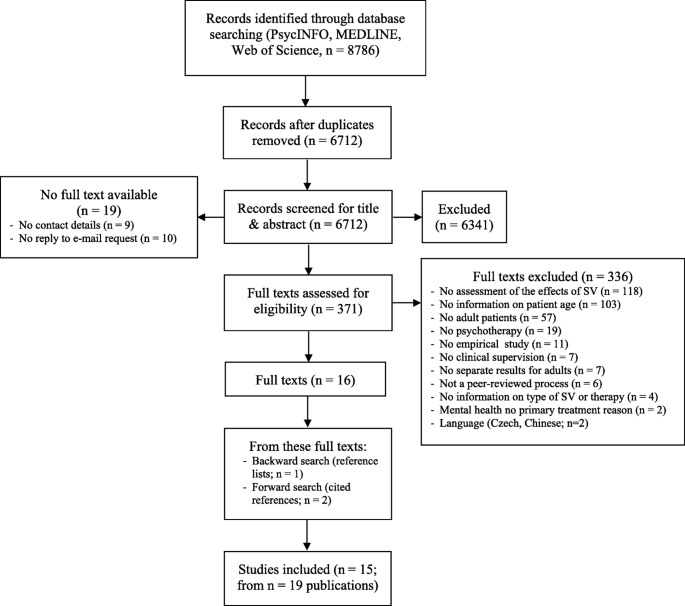

The bibliographic database search was conducted during February and March 2017 in key electronic mental health databases (Fig. 1 ). To include the current evidence, we focused our search on studies published from 1996 onwards. There were no language restrictions. The following search strategy was used: supervis* AND (psychotherap* OR cognitive-behav* OR behav* therapy OR CBT OR psychodynamic OR psychoanaly* OR occupational therapy OR family therapy OR marital therapy) NOT (management OR employ* OR child* OR adolesc*). Then, we inspected the reference lists of the included studies (backward search) and conducted a cited reference search (forward search). We finished our search in July 2017.

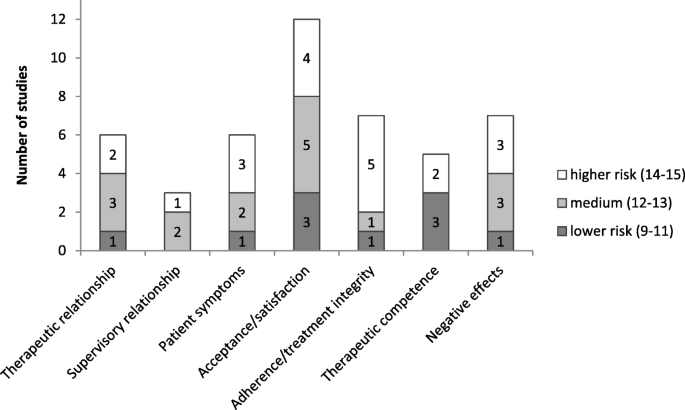

Flowchart on study selection. Adapted from Moher and colleagues (15); SV: supervision

Screening and extraction

Referring to Perepletchikova, Treat and Kazdin [ 26 ], one reviewer (FK) introduced two Master’s psychology students (JM, SW) to the review methods, and the group discussed the review process in weekly one-hour sessions. First, titles and abstracts were screened for inclusion (JM, SW). The first 10% ( n = 671) of all titles and abstracts were screened by both raters independently. Inter-rater agreement regarding title/abstract screening amounted to κ = .83 [CI = .73–.93], which is considered high [ 27 ].

Next, full texts of eligible and unclear studies were retrieved and then screened again independently by both raters (JM, SW). Disagreements were resolved through discussion or through the inclusion of a third reviewer (FK). If publications were not available through inter-library loans, a copy was requested from the corresponding author. For nine authors, contact details were not retrievable, and out of the 15 authors that were contacted, five replied. Inter-rater agreement concerning full text screenings for inclusion/exclusion was κ = .87 [CI = .77–.97].

For data extraction, we used a structured form that was piloted by three reviewers (FK, JM, SW) on five studies. It comprised information on supervision characteristics (e.g., setting, implementation and competence) and study characteristics (e.g., design, main outcome). Data were extracted independently by two raters, the results were then compared, and disagreements resolved again by mutual inspection of the original data.

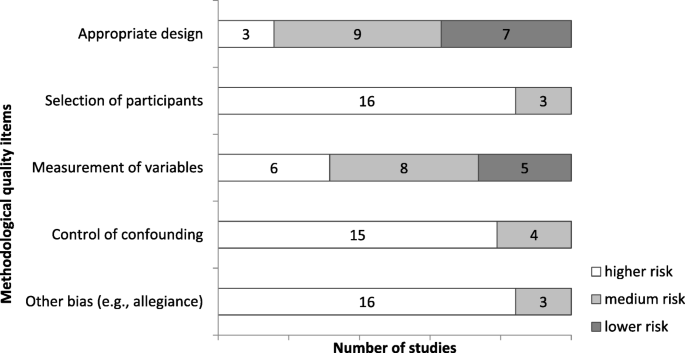

Methodological quality

Since we included various study designs, we could not refer to one common tool for the assessment of methodological quality. We therefore developed a comprehensive tool applicable to various study designs to allow for comparability between studies. For the development, we followed prominent recommendations [ 27 , 28 , 29 ]. The items were as follows: a) an appropriate design regarding the study question; b) the selection of participants; c) measurement of variables/data collection; d) control/consideration of confounding variables; and e) other sources of bias (such as allegiance bias or conflicts of interest). Every item was rated on whether low (1), medium (2) or high (3) threats to the methodological quality were supposed. The resulting sum score ranges from 5 to 15, with higher values indicating the possibility of greater threats to the methodological quality. The methodological quality was rated by two review authors independently (JM or SW and FK). Inter-rater reliability for the sum scores reached ICC (1, 2) = .88 [CI = .70–.95], which is considered high [ 30 ]. Disagreements in ratings were again resolved through discussion within the review group.

Due to the heterogeneity of the study designs and outcomes, we will present the review results narratively and in clearly arranged evidence tables.

Current status of supervision

Psychotherapies.