NP Pulse: The Voice of the Nurse Practitioner (AANP)

https://feed.podbean.com/aanp/feed.xml

The American Association of Nurse Practitioners® (AANP) brings you discussions around the most important topics and issues related to nurse practitioner (NP) practice, education, advocacy, research and leadership. Tune in each month for stories and in-depth conversations with NPs and health care leaders who you can’t hear anywhere else.

Wednesday Jul 19, 2023

90.Type 2 Diabetes: Case Studies in Individualized Care

Diabetes affects more than 37 million Americans, which is about 11% of the population. Approximately 90-95% of people with diabetes have Type 2 diabetes (T2D), and people living with T2D are increasingly cared for by nurse practitioners (NPs). On today’s podcast we are joined by NPs Drs. Shannon Idzik and Kathryn Evans-Kreider to discuss case studies of commonly encountered issues in the management of T2D. Listen in and think about how you would approach the development of the management plans for these patients described in the case studies.

This AANP-accredited podcast, "Type 2 Diabetes: Case Studies in Individualized Care," is part of a six-part series in the “Clinical Advantage Bootcamp: Type 2 Diabetes Management Certificate for Nurse Practitioners,” which was funded by independent medical educational grants from Mylan Inc., a Viatris Company, and Novo Nordisk Inc.

To earn 1.25 contact hours of continuing education (CE) credit for this episode, you will need the participation code provided at the end of the podcast. To claim your CE credit, log in and register for the activity within the AANP CE Center , then enter the participation code and complete the post-test and evaluation. CE credit is available for this podcast through July 2024.

- Download 24.6K

Comments (0)

To leave or reply to comments, please download free Podbean iOS App or Android App

No Comments

To leave or reply to comments, please download free Podbean App.

Nurse Practitioner-Based Diabetes Care Management

Impact of Telehealth or Telephone Intervention on Glycemic Control

- Original Research Article

- Published: 07 October 2012

- Volume 15 , pages 377–385, ( 2007 )

Cite this article

- Karen Chang 1 ,

- Rita Davis 2 ,

- Judy Birt 2 ,

- Pete Castelluccio 1 ,

- Peter Woodbridge 2 &

- David Marrero 3

95 Accesses

10 Citations

Explore all metrics

Limited evidence exists on the impact of nurse practitioner-managed diabetes mellitus care coordination programs in the primary care setting and specifically on the use of telehealth to manage veterans with diabetes in the home.

To compare the impact of nurse practitioner-based diabetes mellitus care management programs using either a telehealth or a telephone intervention. Specific aims were to (i) compare the efficacy of telehealth and telephone interventions in a diabetes care management program, with regards to glycemic control; (ii) examine the impact of program exposure on the control of diabetes following patient disenrollment from the program; and (iii) identify the average duration of use of a telehealth or telephone intervention required to reach individualized glycemic goals.

Design, setting, and patient population

A retrospective pre-post cohort study of a nurse practitioner-managed diabetes care coordination program was performed in primary care clinics in a Midwest Veterans Administration Medical Center in the US. The cohort included in this study consisted of 259 patients who were enrolled in the program between August 2003 and October 2005 and who disenrolled from the program before January 2006.

The mean reductions in glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA 1c ) associated with the program were 2.4% for the telehealth intervention (baseline 9.86%; end of program 7.46%) and 2.39% for telephone intervention (baseline 9.75%; end of program 7.36%). No significant difference in the reduction in HbA 1c was noted between telehealth and telephone interventions (p = 0.96) after adjusting for baseline HbA 1c and age.

The number of days of participation in the program was greater for the telehealth group than the group receiving the telephonic intervention (192.2 vs 161.9) but this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.13). Approximately 75% of the patients (n = 192) worked with nurse practitioners and had reached individualized glycemic goals at disenrollment. Among these patients, those receiving the telehealth intervention had a 3.1% (SD = 1.9, p < 0.001) reduction in HbA 1c and those receiving the telephone intervention had a 2.7% (SD = 1.9, p < 0.001) reduction in HbA 1c , over a mean period of 204 days.

Both interventions lost some of their effect following program disenrollment. The mean rise in HbA 1c in the post-program period was 0.69% for the telehealth intervention and 0.63% for the telephone intervention (the average number of post-program days was 434 days for the telehealth intervention and 323 days for the telephone intervention). After adjusting for HbA 1c at disenrollment and the number of days between disenrollment and the latest HbA 1c measurement, no significant difference in the rise in HbA 1c was seen between the two interventions (p = 0.80).

When employed for a comparable number of days, telehealth and telephone communication technologies used by nurse practitioners to provide individualized diabetes care management have similar effects on glycemic control. After disenrollment, HbA 1c increased slightly, suggesting that veterans need continuous individualized care, in addition to routine follow-up, to manage their diabetes.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Effects of nurse telesupport on transition between specialized and primary care in diabetic patients: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial.

Evaluation of a clinical pharmacist team-based telehealth intervention in a rural clinic setting: a pilot study of feasibility, organizational perceptions, and return on investment

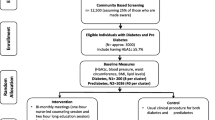

NUrse-led COntinuum of care for people with Diabetes and prediabetes (NUCOD) in Nepal: study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial

Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HA, et al. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ 2000 Aug 12; 321(7258): 405–12

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Testa MA, Simonson DC. Health economic benefits and quality of life during improved glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized, controlled, double-blind trial. JAMA 1998 Nov 4; 280(17): 1490–6

American Diabetes Association. Clinical practice recommendations. Diabetes Care 2007 Jan; 30 (Suppl. 1): S1–103

Google Scholar

Mitka M. Diabetes management remains suboptimal: even academic centers neglect curbing risk factors. JAMA 2005 Apr 20; 293(15): 1845–6

Rundall TG, Shortell SM, Wang MC, et al. As good as it gets? Chronic care management in nine leading US physician organisations. BMJ 2002 Oct 26; 325(7370): 958–61

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Vijan S, Hayward RA, Ronis DL, et al. Brief report: the burden of diabetes therapy. Implications for the design of effective patient-centered treatment regimens. J Gen Intern Med 2005 May; 20(5): 479–82

Knight K, Badamgarav E, Henning JM, et al. A systematic review of diabetes disease management programs. Am J Manag Care 2005 Apr; 11(4): 242–50

PubMed Google Scholar

Loveman E, Royle P, Waugh N. Specialist nurses in diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2003; (2): CD003286

Mullen BA, Kelley PAW. Diabetes nurse case management: an effective tool. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2006 Jan; 18(1): 22–30

Taylor CB, Miller NH, Reilly KR, et al. Evaluation of a nurse-care management system to improve outcomes in patients with complicated diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003; 26(4): 1058–63

Shojania KG, Ranji SR, McDonald KM, et al. Effects of quality improvement strategies for type 2 diabetes on glycemic control: a meta-regression analysis. JAMA 2006 Jul; 296(4): 427–40

Chumbler NR, Vogel WB, Garel M, et al. Health services utilization of a care coordination/home-telehealth program for veterans with diabetes: a matchedcohort study. J Ambulat Care Manag 2005 Jul–Sep; 28(3): 230–40

Shea S, Weinstock RS, Starren J, et al. A randomized trial comparing telemedicine case management with usual care in older, ethnically diverse, medically underserved patients with diabetes mellitus. J Am Med Informatics Assoc 2006 Jan–Feb; 13(1): 40–51

Article Google Scholar

Noel HC, Vogel DC, Erdos JJ, et al. Home telehealth reduces healthcare costs. Telemed J E-Health 2004; 10(2): 170–83

Joseph AM. Care coordination and telehealth technology in promoting self-management among chronically ill patients. Telemed J E-Health 2006 Apr; 12(2): 156–9

Krein SL, Klamerus ML, Vijan S, et al. Case management for patients with poorly controlled diabetes: a randomized trial. Am J Med 2004 Jun 1; 116(11): 732–9

Miller DR, Safford MM, Pogach LM. Who has diabetes? Best estimates of diabetes prevalence in the Department of Veterans Affairs based on computerized patient data. Diabetes Care 2004 May; 27 Suppl. 2: B10–21

Reiber GE, Koepsell TD, Maynard C, et al. Diabetes in nonveterans, veterans, and veterans receiving Department of Veterans Affairs health care. Diabetes Care 2004 May; 27 Suppl. 2: B3–9

United States Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Care Coordination. Care coordination/home telehealth (CCHT) in VA and what it means for veteran patients. 2007 Jan 16 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.va.gov/occ/VetCCHT.asp [Accessed 2007 Mar 17]

Diabetes Mall. Health through information: rules for control [online]. Available from URL: http://www.diabetesnet.com/diabetes_control_tips/corr_factor.php [Accessed 2007 Nov 7]

Walsh J, Warma C, Bailey T. Using insulin. San Diego (CA): Torrey Pines Press, 2003

Krumholz HM, Currie PM, Riegel B, et al. A taxonomy for disease management: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Disease Management Taxonomy Writing Group. Circulation 2006 Sep 26; 114(13): 1432–5

The California Medi-Cal Type 2 Diabetes Study Group. Closing the gap: effect of diabetes case management on glycemic control among low-income ethnic minority populations. The California Medi-Cal Type 2 Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care 2004 Jan; 27(1): 95–103

Chumbler NR, Vogel WB, Garel M, et al. Health services utilization of a care coordination/home-telehealth program for veterans with diabetes. J Ambulat Care Manag 2005 Jul–Sep; 28(3): 230–40

Marrero DG. Changing patient behavior. Endocr Pract 2006 Jan–Feb; 12 Suppl. 1: 118–20

Download references

Acknowledgments

This study received no funding support. Dr Karen Chang completed this study during her postdoctoral fellowship at VA Health Service Research Department. Peter Woodbridge received partial funding for the development of the diabetes telehealth module in collaboration with American Telecare, Inc. The other authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the contents of this study.

The authors acknowledge Betty Dameron, Associate Chief Nursing Service for Clinical Operations at Roudebush VA Medical Center for her initiation of the nurse practitioner-based diabetes care management program, Dr James Walsh for providing prompt endocrinology consultation, and Dr Laura Sands for statistical consultation.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Center on Implementing Evidence-Based Practice, Health Services Research Department, Roudebush Veterans Administration Medical Center, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA

Karen Chang ( Assistant Professor and Director of Information Technology ) & Pete Castelluccio

Ambulatory Care Department, Roudebush Veterans Administration Medical Center, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA

Rita Davis, Judy Birt & Peter Woodbridge

Division of Endocrinology & Metabolism, Indianapolis University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA

David Marrero

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Karen Chang .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Chang, K., Davis, R., Birt, J. et al. Nurse Practitioner-Based Diabetes Care Management. Dis-Manage-Health-Outcomes 15 , 377–385 (2007). https://doi.org/10.2165/00115677-200715060-00005

Download citation

Published : 07 October 2012

Issue Date : December 2007

DOI : https://doi.org/10.2165/00115677-200715060-00005

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Glycemic Control

- Nurse Practitioner

- Baseline HbA1c

- Telephone Intervention

- Glycemic Goal

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

1 hr 12 min

90.Type 2 Diabetes: Case Studies in Individualized Care NP Pulse: The Voice of the Nurse Practitioner (AANP)

Diabetes affects more than 37 million Americans, which is about 11% of the population. Approximately 90-95% of people with diabetes have Type 2 diabetes (T2D), and people living with T2D are increasingly cared for by nurse practitioners (NPs). On today’s podcast we are joined by NPs Drs. Shannon Idzik and Kathryn Evans-Kreider to discuss case studies of commonly encountered issues in the management of T2D. Listen in and think about how you would approach the development of the management plans for these patients described in the case studies. This AANP-accredited podcast, "Type 2 Diabetes: Case Studies in Individualized Care," is part of a six-part series in the “Clinical Advantage Bootcamp: Type 2 Diabetes Management Certificate for Nurse Practitioners,” which was funded by independent medical educational grants from Mylan Inc., a Viatris Company, and Novo Nordisk Inc. To earn 1.25 contact hours of continuing education (CE) credit for this episode, you will need the participation code provided at the end of the podcast. To claim your CE credit, log in and register for the activity within the AANP CE Center, then enter the participation code and complete the post-test and evaluation. CE credit is available for this podcast through July 2024.

- Episode Website

- More Episodes

- Copyright 2020 All rights reserved.

Real World NP

Diabetes case study in mentorship for nurse practitioners.

So many new grads are most worried about building their clinical knowledge base-- for good reason!

But it’s one thing to prepare for clinical topics-- researching algorithms, choosing the best practice based on the evidence-- but an entirely different experience trying to apply them to the “real world.”

Through Real World NP, I have the awesome privilege to work with new grad nurse practitioners on-on-one in mentorship calls.

Some of mentorship is reassuring new grad NPs about their clinical judgment decisions, and it also involves discussing the most up to date guidelines.

But there’s another level to mentorship and “real world” practice that you just can’t get in school.

This week, I want to share with you some of the “behind the scenes” of what our mentoring conversations are like. I’m covering an example patient case with complex diabetes and medical conditions that I reviewed with a real-life new grad nurse practitioner during a mentoring conversation.

Full disclosure: I hope to someday record a call with a new grad NP (with consent and voice-masking, of course), but for now, it’s just me talking, reviewing what we talked about and the variety of ways we approached the situation.

Hopefully this helps you apply these lines of thinking to your own patient cases!

Read the blog post here.

-----------------------

Don't forget to grab your free Ultimate Resource Guide for the New NP at https://www.realworldnp.com/guide

Sign up for the Lab Interpretation Crash Course: https://www.realworldnp.com/labs

Grab your copy of the Digital NP Binder: https://www.realworldnp.com/binder

-----------

More episodes

View all episodes.

6. Giving Yourself Permission, Season 2 Recap & What's Next

5. investing in your future: financial planning for nps, 4. empowering equity: transforming clinical spaces with community care, 3. navigating the drama triangle as an np, 2. caretaker fatigue: what is the root cause, 1. are np careers changing, 102. primary care nurse practitioner roundtable: how are we doing after covid, 101. cardiology in primary care with midge bowers, 100. navigating np burnout with cait donovan.

- Center on Health Equity and Access

- Health Care Cost

- Health Care Delivery

- Value-Based Care

Providers' Perspective on Diabetes Case Management: A Descriptive Study

- Nancy Greer, PhD

- Areef Ishani, MD, MS

Providers do not consider nurse case managers as professional identity threats in co-managing patients with diabetes and cardiovascular risk factors.

Objectives:

To address the physicians’ perspective on case management (CM) for diabetes.

Research Design and Methods:

A nested descriptive study in a randomized controlled trial of diabetic patients who had blood pressure >140/90 mm Hg, glycated hemoglobin >9.0%, or lowdensity lipoprotein level >100 mg/dL. Patients received CM (n = 278) versus usual care over a period of 1 year. Surveys were designed to assess physicians’ comfort in working with case managers. At the end of the study physicians whose patients were randomized in the trial were mailed these surveys.

A total of 51 of the 72 providers completed the survey (70.8% response rate). The majority of the providers felt very comfortable working with case managers (91.5 %), found treatment provided by CM to be accurate (93.3%),reported that having case managers increased the likelihood of adherence to the treatment regimens (89.4%), and reported overall improved patient satisfaction with CM (93.5%). Seventy-four percent of the providers reported that working with case managers increased the number of patients who were able to achieve therapeutic goals. Almost all providers (99.74%) reported that they will likely consult case managers for management of poorly controlled diabetes.

Conclusions:

Co-managing diabetes patients with nurse case managers did not undermine the providers’ perceived professional role. In fact, having CM increased the rate of achieving therapeutic goals among patients with diabetes and cardiovascular risk factors.

(Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(1):29-32) We demonstrate that in patients with diabetes, nurse case management leads to:

- Higher provider satisfaction.

- Greater number of patients who are able to achieve therapeutic goals.

- Providers having more time to concentrate on other acute care needs of their patients.

Case management (CM) has been demonstrated to improve diabetes outcomes, including glycemic control, 1,2 hypertension, 3,4 and dyslipidemia. 4 CM has also been demonstrated to improve patient satisfaction 5,6 and patient perception of quality of care received. 7 We are not aware of any studies that comprehensively addressed the providers’ perspective and level of comfort with CM for patients with diabetes.

Little is known about physicians’ perception of their relationships with case managers. A recent meta-analysis8 and systematic review 9 have reported that nurse practitioners (NPs) in general provide the same quality of care as primary care physicians. Physicians could conceivably view case managers as professional identity threats. 8 It is well known that physicians receive increased satisfaction from improved relationships with their patients. 10 Whether delegating the care task to case managers deprives the physicians of job satisfaction is unknown.

The purpose of our study is to define the views of providers regarding intensive diabetes nurse CM involving simultaneous management of 3 cardiovascular risk factors (ie, glycemic control, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia) in patients with diabetes.

The current study was nested in a randomized, unblinded trial of CM versus usual care. The study was conducted at the Minneapolis Veterans Health Care System (MVHCS), Minnesota, and was supported by Veterans Integrated Service Network 23. Primary study outcomes have been reported. 4

As a part of the study, nurses used treatment protocols to independently advance treatment for management of hyperglycemia, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. After the completion of the randomized trial of CM versus usual care, providers whose patients were randomized in the trial were mailed a survey. Provider responses were anonymous. Surveys were sent by a research assistant who coded the surveys for tracking purposes. Only the research assistant was aware of the provider code. One reminder was sent to providers who did not return the survey within 3 weeks.

The survey was developed by the research team and designed to assess the providers’ perceptions of the effectiveness of the study case managers in achieving diabetes outcome goals, their comfort level in working with case managers, and their perceptions of the effect of CM on treatment adherence and patient satisfaction. It also addressed the providers’ familiarity with CM and whether CM gave the providers more time to focus on acute care needs of their patients.

A total of 72 healthcare providers were mailed surveys. These included 60 primary care physicians (37 at the MVHCS and 23 at affiliated Community-Based Outpatient Clinics [CBOCs]), 7 physician assistants (PAs) (4 at MVHCS and 3 at CBOCs), and 5 NPs (2 at MVHCS and 3 at CBOCs). A total of 51 providers (41 physicians, 5 PAs, and 5 NPs) responded to the survey. The overall response rate was 70.8%. The non-responders were 19 physicians and 2 PAs (11 at MVHCS and 10 at CBOCs).

Responses to the survey questions are reported in the . Eighty-five percent of the providers agreed that having CM allowed them to focus on the acute care needs of their patients. Seventy-four percent reported that working with case managers increased the number of patients who were able to achieve therapeutic goals. Most providers felt comfortable working with case managers (91.5%). The majority of providers found the practices of the case managers to be accurate (93.3%) and reported that having CM increased the likelihood of patient adherence to treatment regimens (89.4%) and improved patient satisfaction (93.5%). Providers reported a need for CM in the care of patients with poorly controlled diabetes (83.0%), hypertension (73.9%), and hypercholesterolemia (61.7%). Most providers were satisfied with the feedback they received from case managers (88.9%). Seventy-two percent disagreed with the statement that having case managers impeded the achievement of therapeutic goals. Only 29.6% felt that their patients preferred that a physician manage all their care. All (100%) reported that they would likely refer a patient to case managers for poorly controlled diabetes, while 84.8% were likely to refer for hypertension and 75.6% for hypercholesterolemia management. The majority (95%) reported that they would likely refer patients to case managers if they had 2 or more cardiovascular (CV) risk factors.

Our results suggest that the majority of the providers who had patients with diabetes enrolled in the randomized trial of CM or usual care for multiple risk factors felt comfortable working with case managers. In addition, the majority of providers reported that delegating tasks to case managers did not undermine their perceived professional role. Providers reported nurse CM services to be accurate and accountable. Providers were more likely to observe treatment adherence in patients who were case managed. The latter is consistent with prior studies and has been linked to better diabetes outcomes. 11,12

Our findings also are consistent with a prior survey of 13 physicians whose patients were randomized to CM or usual care. 13 In the latter study, the majority of physicians reported that CM decreased the amount of time they spent with patients and they strongly recommended adopting a CM program.

Despite several studies demonstrating improved patient satisfaction5,6 and quality of life, 1,7 CM for diabetes has not been widely implemented. There have been several barriers implicated in the global implementation of CM for chronic diseases. It has been reported that CM alters the relationship of physicians with other practitioners involved in the care of the patient. 14 Williams and Sibbald 15 have demonstrated that having CM induced a change in roles and identities among doctors and nurses, leading to uncertainty about their respective professional roles among the general practitioners, and may be a major barrier for CM implementation. Our study contradicts this concept. We demonstrate that the providers’ relationship with the case managers does not impact their job satisfaction. In addition, we demonstrate that providers do not view case managers as a threat to their professional identities. The latter does not constitute a major barrier in the implementation of diabetes CM.

There are limitations to our study. First, we did not pilot the survey we used in the study. Piloting is important to ensure the questions are clear and are not misleading. Second, this study may be unique to Minneapolis Veterans Heath Care system (VA) providers, who generally treat an older population of veterans with several comorbidities, and hence their views could differ from those of the providers outside the VA practice. The VA system does not have the typical fee-for-service construct, and therefore the likelihood of acceptance may be higher because case managers are not perceived as competition. In addition, the impact of CM on physician reimbursements could not be determined. Third, when analyzing provider responses, we were unable to account for the individual patient outcomes in the study. Lastly, the inherent limitation of using the Likert scale is the central tendency bias and social desirability bias where the providers portray themselves in a more favorable light which may not represent their true views.

Key problems with CM implementation for different disease models have been reported to be uncertain identities 15 and relationships within a practice team. 14 Our study contradicts this concept and indicates that neither factor is a barrier to global implementation of CM in diabetes. This is consistent with the results of the study by Taylor et al. 13 However, it is imperative that our results are confirmed in fee-for-service healthcare settings prior to global implementation of CM.

The study case managers (an NP and an RN who was also a Certified Diabetes Educator) were highly experienced in managing patients with diabetes. Whether our findings would be replicated with less-experienced case managers is unknown.

CM has been demonstrated to improve CV risk factors. Patients have greater satisfaction with CM. The present study demonstrates that CM also improves physician satisfaction.

Author Affiliations: From VA Health Care System (NE-F, NG, AI), Minneapolis, MN; Department of Medicine (NE-F, KG, AI), University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN; Center for Chronic Disease Outcome Research (NG), Minneapolis VA Health Care System, Minneapolis, MN.

Funding Source: This study was funded by a Veterans Integrated Service Network 23 Grant.

Author Disclosures: The authors (NE-F, KG, NG, AI) report no relationship or financial interest with any entity that would pose a conflict of interest with the subject matter of this article.

Authorship Information: Concept and design (NE-F, KG, NG, AI); acquisition of data (NE-F, KG, NG, AI); analysis and interpretation of data (NE-F, KG, NG, AI); drafting of the manuscript (NE-F, KG, AI); critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content (NE-F, KG, NG, AI); statistical analysis (NE-F, KG); provision of study materials or patients (NE-F, NG); obtaining funding (NE-F, AI); administrative, technical, or logistic support (NG); and supervision (NE-F, AI).

Address correspondence to: Nacide Ercan-Fang, MD, Associate Professor of Medicine, University of Minnesota, Metabolic Staff Physician, VA Medical Center, 1 Veterans Dr 111G, Minneapolis, MN 55417. E-mail: [email protected]. Aubert RE, Herman WH, Waters J, et al. Nurse case management to improve glycemic control in diabetic patients in a health maintenance organization: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129(8):605-612.

2. Thompson DM, Kozak SE, Sheps S. Insulin adjustment by a diabetes nurse educator improves glucose control in insulin-requiring diabetic patients: a randomized trial. CMAJ. 1999;161(8):959-962.

3. Carter BL, Rogers M, Daly J, Zheng S, James PA. The potency of team-based care interventions for hypertension: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(19):1748-1755.

4. Ishani A, Greer N, Taylor BC, et al. Effect of nurse case management compared with usual care on controlling cardiovascular risk factors in patients with diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(8):1689-1694.

5. Krein SL, Klamerus ML, Vijan S, et al. Case management for patients with poorly controlled diabetes: a randomized trial. Am J Med. 2004;116(11):732-739.

6. Sutherland D, Hayter M. Structured review: evaluating the effectiveness of nurse case managers in improving health outcomes in three major chronic diseases. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18(21):2978-2992.

7. Houweling ST, Kleefstra N, van Hateren KJ, et al. Diabetes specialist nurse as main care provider for patients with type 2 diabetes. Neth J Med. 2009;67(7):279-284.

8. Brown SA, Grimes DE. A meta-analysis of nurse practitioners and nurse midwives in primary care. Nurs Res. 1995;44(6):332-339.

9. Horrocks S, Anderson E, Salisbury C. Systematic review of whether nurse practitioners working in primary care can provide equivalent care to doctors. BMJ. 2002;324(7341):819-823.

10. Stoddard JJ, Hargraves JL, Reed M, Vratil A. Managed care, professional autonomy, and income: effects on physician career satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(10):675-684.

11. Jacobson AM, Adler AG, Derby L, Anderson BJ, Wolfsdorf JI. Clinic attendance and glycemic control: study of contrasting groups of patients with IDDM. Diabetes Care. 1991;14(7):599-601.

12. Hammersley MS, Holland MR, Walford S, Thorn PA. What happens to defaulters from a diabetic clinic? Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1985; 291(6505):1330-1332.

13. Taylor CB, Miller NH, Reilly KR, et al. Evaluation of a nurse-care management system to improve outcomes in patients with complicated diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(4):1058-1063.

14. Halcomb EJ, Davidson PM, Griffiths R, Daly J. Cardiovascular disease management: time to advance the practice nurse role? Aust Health Rev. 2008;32(1):44-53.

15. Williams A, Sibbald B. Changing roles and identities in primary health care: exploring a culture of uncertainty. J Adv Nurs. 1999; 29(3):737-745.

Download PDF: Providers' Perspective on Diabetes Case Management: A Descriptive Study

Defragmentation of Care in Complex Patients With ESKD Improves Clinical Outcomes

A novel program utilizing an approach to defragment care for patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) resulted in better patient outcomes.

Policy Changes, Advocacy Are Key Components in Closing Gaps in Behavioral Health

Gaps in the delivery and coverage of behavioral health care can be addressed through continued advocacy for better policies and financial incentives surrounding treatment.

Risk Assessments of Drug-Related Problems for Cardiac Surgery Patients

Risk assessments of drug-related problems for cardiac surgery patients can be conducted by implementing a framework for patient safety.

Medication Adherence Star Ratings Measures, Health Care Resource Utilization, and Cost

For patients prescribed diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia medications, nonadherence to CMS Star Ratings quality measures of medication adherence was associated with increased health care resource utilization and costs.

Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Regular Emergency Department Users

Regular users of the emergency department (ED) transiently reduced ED visits when faced with ED access barriers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Traditional Medicare Supplemental Insurance and the Rise of Medicare Advantage

Rising Medicare Advantage enrollment occurred alongside declines in enrollment in traditional Medicare with employer-sponsored supplemental coverage and traditional Medicare without supplemental coverage.

2 Commerce Drive Cranbury, NJ 08512

609-716-7777

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Why Advanced Practice in Diabetes Care?

What is the bc-adm credential, advanced practice care: advanced practice care in diabetes: preface.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Cite Icon Cite

- Get Permissions

Anne Daly; Advanced Practice Care: Advanced Practice Care in Diabetes: Preface. Diabetes Spectr 1 January 2003; 16 (1): 24–26. https://doi.org/10.2337/diaspect.16.1.24

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Today is a remarkable time in diabetes care. Diabetes has reached epidemic proportions worldwide. An estimated 17 million Americans have this deadly disease, while another 16 million have pre-diabetes, or impaired glucose tolerance (IGT). With the aging of the U.S. population and our increasing life expectancy, the demand for diabetes care is only expected to increase. Recognition is growing that diabetes is a serious disease and a major contributor to escalating health care costs. The costs of the disease as well as concerns about access to quality diabetes care are making diabetes a national priority.

At the same time, diabetes care has become increasingly sophisticated. Diabetes research has resulted in newer insulins and medications, better systems for insulin delivery and self-monitoring of blood glucose, and more aggressive treatment of diabetes complications and comorbid conditions. Clinical care of diabetes has more treatment options than ever before, and many more are in the pipeline.

Simultaneously, changes in the health care system and public policy have shifted diabetes treatment from acute care settings, such as hospitals, toward outpatient facilities and managed care organizations. The drive to identify cost-effective treatment is intense. Increasingly, health care professionals who specialize in the care of people with chronic illnesses such as diabetes are increasingly recognized as an important group. A greater focus on health promotion and prevention is increasingly evident. Diabetes health care providers seek to expand their niche in today’s health care environment. The team approach to diabetes care has long been advocated, and the benefits of a team approach to diabetes management have been well documented. 1 – 4

Still another driving force in diabetes care today is the changing face of the American public. As baby boomers join the ranks of the “elderly,” consumers continue to become more knowledgeable, more politically active, and more insistent about the health care they receive. Consumers want quality care that is accessible and cost-effective.

These factors and others have set the stage for significant changes in how diabetes care has been provided over the past decade. Most disciplines involved in diabetes care have developed professional practice standards for diabetes, and standardized outcome measurement tools have been developed and are in use. Indeed, diabetes care has developed into a highly specialized field with an emerging trend toward advanced practice-level care—the topic of this From Research to Practice section.

Numerous studies, including the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial, 5 the Kumamoto Study, 6 and the U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study, 7 have demonstrated that intensive diabetes management can reduce the risk of onset and progression of long-term complications of diabetes. Most recently, the Diabetes Prevention Program 8 provided further evidence for the benefit of providing intensive therapy to patients with IGT to prevent, or at least delay, the onset of diabetes. The intensive management offered within these landmark studies required and exemplified a higher level of skill for the health care team members working with diabetes patients and their families. The stage was being set for the development of an advanced practice credential for clinical diabetes managers.

These studies 5 – 8 offered major opportunities for health care professionals to expand their roles beyond traditional boundaries and to demonstrate their effectiveness in performing at an advanced level of practice. 9 , 10 Several studies 11 – 14 have suggested that the quality of care provided by primary care nurse practitioners is equal to that provided by physicians or leads to the same outcomes as care provided by primary care physicians. 9

Some potential benefits of adding advanced diabetes managers to primary care include cost containment and improved quality and continuity of care. Additionally, as health professionals earn the credential of advanced diabetes manager, they will be available and identifiable for consultation, education, management, and research. Advanced practice diabetes managers will serve as role models and leaders who creatively adapt to our rapidly changing health care system.

In 1993, the American Association of Diabetes Educators (AADE) and the American Diabetes Association created a task force to review the role of advanced practice nurses in diabetes care and discuss ways to achieve recognition for the unique part they play within the diabetes care team. In advanced practice, clinical care was added to the skill set of the widely recognized and established certified diabetes educator (CDE) credential, and this addition created the need for a means of verifying clinical care skills among advanced practitioners. The Board Certified—Advanced Diabetes Manager (BC-ADM) credential was developed to meet this need.

As discussion about the possible development of a new credential continued, members of this task force realized that, because of the interdisciplinary nature of diabetes care teams, the need for a new advanced diabetes manager credential reached beyond the nursing profession. The goal of the task force thus expanded to include advanced practitioners not only in nursing, but also in the disciplines of nutrition and pharmacy.

AADE soon invited the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), the world’s largest certifying/credentialing organization for nurses, to join the discussion, and ANCC lent its reputation of credibility and excellence to this important project. The Commission on Dietetic Registration of The American Dietetic Association and the American Pharmaceutical Association also supported the concept of this new credential and became involved in its planning and development.

Role delineation studies to determine information about professional practices were conducted for four practice groups: registered nurses, clinical nurse specialists and nurse practitioners, registered dietitians, and registered pharmacists. A Content Expert Panel (CEP) was appointed to develop the test content outline for the new credential based on the results of the role delineation studies. The CEP developed an outline based on equal expectations for all disciplines working in diabetes.

Numerous surveys were conducted within constituent groups to verify the level of interest in the development of a new credential. Test item writers were trained, and four distinct versions of the exam were created: one each for nurse practitioners, clinical nurse specialists, dietitians, and pharmacists. And the BC-ADM credential was born.

This multidisciplinary credential is the culmination of many years of effort by several organizations. Available for nurses, dietitians, and pharmacists who have advanced degrees, it is different from the CDE credential in that it focuses on advanced clinical management of diabetes. Although advanced practice dietitians, pharmacists, and nurses seeking certification take different versions of the examination designed specifically for their own profession, all of the exams cover the domains of clinical practice, collaboration, research, patient and professional diabetes education, and public and community health.

The first BC-ADM examination was offered in the spring of 2002. Exams are now available via computer at Sylvan Learning Centers across the country. At present, more than 300 diabetes health professionals can identify themselves as BC-ADMs. For more information on attaining certification, visit www.nursecredentialing.org , www.ncbde.org , or www.aadenet.org .

Because advanced practice in diabetes care is still evolving, it is interesting to look at the components of advanced practice roles and at some examples of how diabetes care can be enhanced using advanced practice diabetes managers. Many practitioners are wondering about the new BC-ADM credential and evaluating the possible benefits to their own professional situation. 15 Other practitioners are planning their career paths with an eye toward becoming advanced practice diabetes managers in the future.

In this issue, we are most fortunate to have a group of highly experienced and skilled diabetes clinicians as authors. First, Virginia Valentine, CNS, BC-ADM, CDE, Karmeen Kulkarni, MS, RD, BC-ADM, CDE, and Debbie Hinnen, ARNP, BC-ADM, CDE, provide an overview of the new credential, including how it evolved, what it means, and how it differs from the CDE credential ( p. 27 ). Next, three more advanced practice clinicians, one from each discipline eligible for the BC-ADM, present actual cases from their practices that illustrate their role as advanced diabetes managers. Geralyn Spollett, MSN, C-ANP, CDE, presents a patient with type 2 diabetes and a complex set of comorbidities ( p. 32 ). Claudia Shwide-Slavin, MS, RD, BC-ADM, CDE, discusses her role in treating a patient with type 1 diabetes and hypoglycemia unawareness ( p. 37 ). And Peggy Yarborough, PharmD, MS, BC-ADM, CDE, FAPP, FASHP, NAP, reviews her role in managing a patient with type 2 diabetes and asthma, who was referred for pharmacotherapy assessment and diabetes management ( p. 41 ). Finally, co–guest editor Davida F. Kruger, MSN, APRN, BC-ADM, offers her perspective on the future of advanced practice in diabetes care ( p. 49 ).

We hope this issue dedicated to the topic of advanced diabetes management will help explain what the new BC-ADM credential is, why it was developed, and how it might be applied in the clinical practice of each discipline. We encourage all eligible diabetes health care professionals to seriously consider whether this new credential could enhance their own practice settings and professional growth.

Email alerts

- Advanced Practice Care: Advanced Practice Care in Diabetes: Epilogue

- Evolving Roles: From Diabetes Educators to Advanced Diabetes Managers

- Case Study: A Patient With Type 1 Diabetes Who Transitions to Insulin Pump Therapy by Working With an Advanced Practice Dietitian

- Case Study: A Patient With Uncontrolled Type 2 Diabetes and Complex Comorbidities Whose Diabetes Care Is Managed by an Advanced Practice Nurse

- Case Study: A Patient With Type 2 Diabetes Working With an Advanced Practice Pharmacist to Address Interacting Comorbidities

- Online ISSN 1944-7353

- Print ISSN 1040-9165

- Diabetes Care

- Clinical Diabetes

- Diabetes Spectrum

- Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes

- Scientific Sessions Abstracts

- BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care

- ShopDiabetes.org

- ADA Professional Books

Clinical Compendia

- Clinical Compendia Home

- Latest News

- DiabetesPro SmartBrief

- Special Collections

- DiabetesPro®

- Diabetes Food Hub™

- Insulin Affordability

- Know Diabetes By Heart™

- About the ADA

- Journal Policies

- For Reviewers

- Advertising in ADA Journals

- Reprints and Permission for Reuse

- Copyright Notice/Public Access Policy

- ADA Professional Membership

- ADA Member Directory

- Diabetes.org

- X (Twitter)

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Terms & Conditions

- Get Adobe Acrobat Reader

- © Copyright American Diabetes Association

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

2 Diabetes Nurse Practitioner Programs

Top 3 Benefits Of Diabetes Nurse Practitioner Programs

Benefit #1: bc-adm certification, benefit #2: salary, benefit #3: employment opportunities, what diabetes nurse practitioner programs are currently available, 1. yale university - new haven, ct.

Program Type: MSN (Diabetes Care Concentration)

2. University of Southern Indiana - Evansville, IN

Program Type: Certificate (Diabetes Management Program)

Where Do Diabetes Nurse Practitioners Mostly Work?

Work setting #1: hospitals, work setting #2: primary care practices, work setting #3: long-term care facilities, starting salary for diabetes nurse practitioners, average salary for diabetes nurse practitioners, my final thoughts, frequently asked questions answered, 1. on average, how much do diabetes nurse practitioners make per hour, 2. on average, how much do diabetes nurse practitioners make per week, 3. on average, how much do diabetes nurse practitioners make per month, 4. on average, how much do diabetes nurse practitioners make per year, 5. what are the 10 highest paying states for diabetes nurse practitioners, 6. what are the 10 highest paying cities for diabetes nurse practitioners.

- Acute Care Nurse Practitioner Programs

- Addiction Nurse Practitioner Programs

- Adult Gerontology Nurse Practitioner Programs

- Cardiology Nurse Practitioner Programs

- Critical Care Nurse Practitioner Programs

- Dermatology Nurse Practitioner Programs

- Emergency Nurse Practitioner Programs

- Endocrinology Nurse Practitioner Programs

- Family Nurse Practitioner Programs

- Forensic Nurse Practitioner Programs

- Functional Medicine Nurse Practitioner Programs

- Holistic Nurse Practitioner Programs

- Internal Medicine Nurse Practitioner Programs

- Neonatal Nurse Practitioner Programs

- Nephrology Nurse Practitioner Programs

- Occupational Health Nurse Practitioner Programs

- Oncology Nurse Practitioner Programs

- Orthopedic Nurse Practitioner Programs

- Palliative Care Nurse Practitioner Programs

- Pediatric Nurse Practitioner Programs

- Pediatric Oncology Nurse Practitioner Programs

- Pediatric Psychiatric Nurse Practitioner Programs

- Psychiatric Mental Health Nurse Practitioner Programs

- Public Health Nurse Practitioner Programs

- Surgical Nurse Practitioner Programs

- Trauma Nurse Practitioner Programs

- Womens Health Nurse Practitioner Programs

- Connecticut

- Massachusetts

- Mississippi

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- West Virginia

- Journal of Diabetes Nursing

Vol:07 | No:10

Nurse prescribing in diabetes care: a case study

- 20 Nov 2003

In 1986, the Cumberlege Report (DHSS, 1986) highlighted the valuable skills of community nurses in selecting appropriate dressings and appliances and the time wasted waiting for general practitioners to sign such prescriptions. As a result it was recommended that suitably qualified community nurses should be able to prescribe from a limited formulary (DoH, 1989) and in 2001, this was extended to include other groups of nurses. There was also an acknowledgement that in other complex conditions such as chronic disease ‘supplementary prescribing’ within a clinical management plan, agreed by the patient, an independent prescriber (doctor or dentist) and a supplementary prescriber (nurse or pharmacist) would benefit patient care. In March this year, guidelines for the implementation for supplementary prescribing were published (DoH, 2003). This article describes the prescribing options currently available to nurses and evaluates the use of a clinical management plan (supplementary prescribing) in the care of a young patient with type 1 diabetes.

Share this article + Add to reading list – Remove from reading list ↓ Download pdf

There are currently two prescribing options available to nurses: independent prescribing and supplementary prescribing (see Figure 1 ).

Independent prescribing In this situation, the nurse prescriber is an independent practitioner who takes responsibility for the initial assessment, diagnosis, clinical management and prescribing for a patient under his or her care.

There are two types of independent nurse prescribers:

- District nurses and health visitors who are able to prescribe from a limited formulary of products focused on their own area of practice e.g. wound care. District nurses and health visitors were the first nurses to be trained for a prescribing role and prescribing is now an integral part of district nurse and health visitor training programmes.

- Extended formulary nurse prescribing enables first level registered nurses to prescribe treatments for a broader range of medical conditions: minor illness, minor injury, health promotion and palliative care. Such nurses are able to prescribe from an extended formulary, including all items listed in the district nurse and health visitors formulary, all licensed pharmacy medicines, all medicines from the general sales list and around 140 prescription-only medicines including selected antibiotics and antifungals. Training involves attending a 25-day training programme (at level 3) and an additional 12 days learning in clinical practice.

Supplementary prescribing Supplementary prescribing is the most recent addition to the prescribing options (DoH, 2003) and is defined as ‘a voluntary relationship between an independent prescriber (doctor or dentist) and a supplementary prescriber to implement a patient-specific clinical management plan with the patient’s agreement’ (National Prescribing Centre, 2003). There are no restrictions on the clinical conditions that a supplementary prescriber may treat, and it is anticipated that it will be most useful in managing chronic conditions such as diabetes. Within this prescribing arrangement, the independent prescriber retains the responsibility for the initial clinical assessment and diagnosis and determines the scope of the clinical management plan. Training is based around that for extended prescribing with an additional 1–2 days relating to the context and scope of supplementary prescribing. Nurses undertaking this training will also be able to prescribe from the nurse prescribers extended formulary.

Supplementary prescribing: a case study Mr Smith attended the diabetes centre, Aintree Hospitals for an annual review earlier this year. At this clinic attendance. he was reviewed by a consultant diabetologist and found to have poor diabetes control (an HbA 1c of 9.9%), raised blood pressure (157/84mmHg) and an elevated albumin/creatinine ratio indicating the possibility of early diabetic nephropathy. Mr Smith was referred to me for assessment of the above risk factors.

The consultation Effective consultation requires two-way communication between the healthcare professional and the patient, with an emphasis on listening and understanding the patient’s perspective (Pendleton et al, 2003, Gask et al, 2002). Several consultation models have been described (Pendleton et al, 2003; Gask et al 2002; Neighbour, 1987) and in this case a ‘three function’ model was utilised (Cole and Bird, 2000). The model breaks the consultation down into three main areas:

- Building the relationship

- Collecting the data

- Agreeing the management plan.

This model was chosen for its simplicity and because it reflects current practice in the diabetes centre.

Building the relationship Mr Smith, aged 30 years, had been attending the diabetes centre for over 10 years since type 1 diabetes was diagnosed. I had not seen him in recent years but I had met him on many occasions in the past. This previous contact formed the basis for the partnership which was to develop over the next few months. Partnership with the patient is a key element in the development of management plans and features heavily in both the supplementary prescribing implementation document (DoH, 2003) and the National Service Framework for Diabetes: Delivery Strategy (DoH, 2002). Important attributes of successful partnerships include power sharing and negotiation with the ultimate aim of empowering the patient to be the prime driver of his own healthcare needs (Gallant et al, 2002).

Collecting the data To help define the clinical problem, it is essential to obtain a history considering physical, psychological and social aspects of well being. Mr Smith is married with two children and he is an office worker. He has had type 1 diabetes for 10 years and has attended the diabetes centre on a regular basis for follow-up care. His diabetes control has always been indifferent or poor (HbA 1c 8–11%). His urinary albumin: creatinine ratio was raised on two occasions at 4.2 and 8.8mg/mmol this year (normal range<2.5mg/mmol), suggesting early diabetic renal disease (NICE Guidelines, 2002).

In addition, his blood pressure was raised at his last clinic appointment. This year at eye screening, Mr Smith was found to have early background retinopathy. His current weight is 92kg (BMI 31) and his blood lipid profile is: total cholesterol 4.4mmol/l, HDL 1.3mmol/l, LDL 2.8mmol/l, triglycerides 1.6mmol/l. He is a lifelong non-smoker and drinks 25 units of alcohol per week. He has no other significant medical history.

Mr Smith’s current medication is: 8 units of soluble insulin pre-breakfast, 6 units pre-lunch and 12 units pre-tea and 24 units of isophane insulin at bedtime. Mr Smith has a family history of cardiovascular disease; his father died prematurely (aged 42 years) from a myocardial infarction having had a stroke in his late 30’s. Two uncles had also died at an early age from cardiovascular causes.

Assessment As part of the assessment, Mr Smith’s blood pressure was measured using the British Hypertension Society’s guidelines (Ramsey et al, 1999). A mean of three recordings, in the sitting position, revealed a blood pressure of 152/82mmHg. This falls outside the target level for blood pressure (<130/80mmHg) in patients with type 1 diabetes and microalbuminuria (European Diabetes Policy Group, 1999).

Mr Smith’s glycaemic control is poor with a HbA 1c of 9.9% (target levels <7.5%, European Diabetes Policy Group 1999). The first line management of poor diabetes control in patients with established type 1 diabetes is lifestyle modification, and therefore a lifestyle assessment was indicated. Mr Smith reported that his diet was high in saturated fat (diary products and chips), his meals were regular and included carbohydrate foods. He is physically inactive and does not achieve the minimum level of activity recommended by Diabetes UK (2003; 30 minutes of physical exercise on a least 5 days per week).

His injection technique is excellent, he rotates his insulin sites on a regular basis and there is no evidence of lipohypertrophy. Poor injection technique and lipohypertrophy is associated with poor diabetes control (Kordonouri et al 2002; Teft, 2002). Mr Smith reported forgetting his insulin injections only occasionally and then making sensible corrections with the next insulin injection.

Adherence with treatment is a particular problem in chronic disease and in diabetes; non-adherence rates as high as 30% have been reported (Morris et al, 1997; Donnan et al, 2002). I was unable to assess Mr Smith’s blood glucose monitoring technique because he did not have his machine with him. Ensuring an accurate technique and performing regular quality control of the machine are important when teaching patients to alter insulin dose. Mr Smith felt generally well and did not report any osmotic symptoms. He reported occasional episodes of nocturnal hypoglycaemia. His home blood glucose monitoring records, although sporadic, revealed fasting blood glucose levels of 10–12mmol/l, with levels rising to over 15 mmol/l during the day.

The following issues were identified:

- Poor glycaemic control

- Hypertension

- Probable diabetic nephropathy and background retinopathy.

Mr Smith’s hypertension and microalbuminuria had not been previously diagnosed, therefore I approached my clinical supervisor/independent prescriber to confirm the diagnosis and agree a clinical management plan (see Figure 2 ). In line with the DoH guidelines for supplementary prescribing (DoH 2003), the independent prescriber is responsible for diagnosis and setting the parameters of the clinical management plan, however, the supplementary prescriber remains accountable for their own actions (Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2002).

Gaining agreement and engaging the patient in the process are important elements of supplementary prescribing. Mr Smith had several risk factors to address and he was happy to work within a management plan.

Agreeing a management plan We started by discussing the risk factor issues and how they could impact on Mr Smith’s future health and well being. His main concern was his family history of cardiovascular disease and the measures he could take to reduce his risk. He was a teenager when his father died and had great concerns for his own children. Mr Smith acknowledged the potential for lifestyle changes. He takes very little exercise and his alcohol intake, although within recommended safe limits, is greater than he would like.

We discussed strategies to reduce weight, such as reducing fat and alcohol intake and increasing physical activity. Mr Smith felt that he has difficulty finding time to take formal exercise and we discussed building some activity into his everyday routine and acknowledged that this would be a gradual process. In agreement with the patient a referral was made to the dietitian. We also discussed the possibility of pharmacological treatments such as orlistat and sibutramine.

Following a discussion about blood glucose levels and insulin doses, Mr Smith opted not to increase his insulin dose but concentrate on lifestyle changes. However, as his blood sugars did rise during the day and he was having nocturnal hypoglycaemia 2–3 times weekly, it was agreed (on the patient’s suggestion) to change his isophane insulin to twice daily: 12 units with breakfast and 12 units at bedtime. We discussed the future possibility of changing the basal insulin to glargine (NICE Guidelines, 2002a) and this was built into the clinical management plan.

During discussion with my clinical supervisor we decided that Mr Smith should have a 24h urine collection. Microalbuminuria was confirmed and he was started on an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor. The basis for this decision was:

- ACE inhibitors have been shown to be renoprotective in type 1 diabetes, delaying the progression from microalbuminuria to overt nephropathy in many patients (ACE Inhibitors Trialist Group 2001; Lovell, 2000; EUCLID Study Group, 1997).

- Mr Smith’s blood pressure is outside the target range and the antihypertensive of choice would be an ACE inhibitor due to its additional renal protective effects (Ramsay et al, 1999; Bakris et al, 2000; NICE Guidelines, 2002; European Diabetes Policy Group, 1999).

- There are no contraindications to ACE inhibitors in this patient.

Lisinopril 5mg was prescribed. This drug is sometimes associated with a dry cough and the patient was informed of this. ACE inhibitors can cause deterioration of renal function and therefore blood urea, creatinine and electrolytes should be checked 7–10 days after starting this class of drug and then after every dose increase. Lisinopril was chosen as it is included in the hospital formulary, we have had considerable experience with it, it is licensed for diabetic nephropathy (British National Formulary, 2003) and is available in a non-proprietary form. The cost for 5mg daily would be £7.86 per month. As drugs expenditure is increasing across the health economy, cost effectiveness must always be considered

Most patients with diabetes and hypertension require several antihypertensive agents (Hansson et al 1998, UKPDS 1998) and this was built into the clinical management plan.

Mr Smith left the diabetes centre with many issues to consider. It is sometimes necessary to prioritise the problems and deal with one at a time. However, this patient’s problems were all inter-related and he was asking many relevant questions. He appeared happy with the management plan and we had set realistic goals particularly relating to increased activity. Whilst I was unable to reassure Mr. Smith about future outcomes I was able to provide support and discuss the treatment options available to reduce the risks. The ultimate aim is for the patient to be able to make informed decisions about their overall management.

Follow-up appointments Mr Smith’s progress was reviewed on a monthly basis. To achieve target blood pressure levels his dose of lisinopril was gradually titrated to 15mg and amlodipine was added to this treatment plan and titrated up to 10mg. Combination therapy is often needed to achieve target blood pressure levels and drugs from a different class often have an additive effect (Ramsay et al, 1999). Mr Smith gradually increased his insulin dose to soluble insulin 12 units pre-breakfast, 12 units pre-lunch and 12 units pre-tea and isophane insulin 16 units pre-breakfast and 16 units pre-tea. His diabetes control, although still not within the target range, improved to 8.8% and his weight remained steady. He did not report any troublesome hypoglycaemia. Improvements in diabetes control have been shown to reduce the risk of microvascular complications in patients with type 1 diabetes (DCCT, 1993). In addition, for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease, aspirin 75mg daily was prescribed when blood pressure was below 150/90mmHg.

Evaluation of clinical management plan The clinical management plan is a legal requirement without which supplementary prescribing cannot take place. It should be drawn up and agreed by the patient, the independent prescriber and the supplementary prescriber and has the benefit of enabling the supplementary prescriber to manage the treatment of individual patients (National Prescribing Centre 2003). Information that must be included in the clinical management plan is shown in Figure 3 .

This case study demonstrates how a combination of lifestyle modifications and pharmacological interventions can have beneficial effects on blood pressure and glycaemic control. Working within a clinical management plan has encouraged partnership and patient participation aiding the delivery of individualised structured care.

Views of the independent prescriber In the past few years, many health visitors and district nurses have become independent prescribers and are able to prescribe from a limited formulary e.g. wound dressings and appliances, devices and blood glucose monitoring equipment. Clearly this has been of considerable benefit to patients. The nurse with intimate knowledge of the patient and familiarity with the products is usually best placed to prescribe appropriately. The introduction of extended independent and supplementary nurse prescribing allows specialist nurses (without a community qualification) to also be involved in the prescribing process. After a prolonged training course (25–26 days) plus 12 days supervised practice, specialist nurses are able to prescribe from an independent formulary or within a clinical management plan.

It is vital, however, that supplementary prescribing occurs in partnership with the patient and the independent prescriber (in diabetes care, usually a consultant diabetologist or general practitioner) and with an agreed clinical management plan. The clinical management plan is of course a set of guidelines which no doubt would have been constructed from the current views of ‘experts’ – from evidence filtered through opinion. Guidelines are, however, not the law and are to be applied according to circumstances e.g. age, motivation and adherence of the patient (Hampton, 2003).

The care of the patient with diabetes must be a partnership between the new nurse prescriber and the patient’s physician. A constant dialogue should occur and wise specialist/practice nurses will know when the management plan is not appropriate and when to seek further advice.

Conclusion The introduction of supplementary prescribing represents an important landmark for nurses working in diabetes. Clinical management plans can be utilised to cover a variety of different treatment areas including glycaemic control, cardiovascular risk factor management and the management of complications such as painful neuropathy. In addition extended prescribing enables nurses to prescribe not only devices and needles but also to prescribe, for example, antifungals to patients suffering symptoms of poor glycaemic control.

The NHS plan (DoH, 2000) highlights the need for service modernisation and defines new roles for nurses and prescribing is one of these roles. New roles will inevitably lead to greater demands and increased accountability and responsibility. Nurses must ensure that they have the skills to carry out these new roles and must continue to work within the code of professional conduct (Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2002).

ACE Inhibitors in Diabetic Nephropathy Trialist Group (2001). Should all patients with type 1 diabetes and microalbuminuria receive angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors? A meta-analysis of individual patient data. Annals of Internal Medicine 143 : 370–79 Bakris GL, Williams M, Divorkin L et al (2000) Preserving renal function in adults with hypertension and diabetes: a consensus approach. American Journal of Kidney Disease 36 : 646–61 British National Formulary (March 2003) Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. London Cole SA, Bird J (2000) The medical interview: the three function approach . Harcourt Health Sciences, St Louis MO Department of Health and Social Security (1986) Neighborhood Nursing – a focus for care (Cumberlege Report). HMSO, London Department of Health (1989) Report of the advisory group on nurse prescribing (Crown Report). HMSO, London Department of Health (2000) The NHS plan: a plan for investment. A plan for reform. DoH, London. Department of Health (2002) National Service Framework for Diabetes: Delivery Strategy . DoH, London. Department of Health (2003) Supplementary prescribing by nurses and pharmacists within the NHS in England: a guide for implementation . DoH, London. Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group (1993) The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression oflong term complications in insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. New England Journal of Medicine 329(14) : 977–86 Diabetes UK (2003) Care recommendation: physical activity and diabetes . Diabetes UK. London Donnan PT, MacDonald TM, Morrist AD (2002) Adherence to prescribed oral hypoglycaemic medication in a population of patients with Type 2 diabetes: a retrospective cohort study. Diabetic Medicine 19(4) : 279–84 EUCLID Study Group (1997) Randomised placebo controlled trial of lisinopril in normotensive patients with insulin dependent diabetes and normoalbuminuria or microalbuminuria. Lancet 349 : 1787–92 European Diabetes Policy Group (1999) A desktop guide to type 1 (insulin dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetic Medicine 16 : 253-256. Gallant MH, Beaulieu MC, Carnevale FA (2002) Partnership: an analysis of the concept within the nurse client relationship. Journal of Advanced Nursing 40 (2): 149-157. Gask L, Usherwood T (2002) ABC of psychological medicine. The consultation. BMJ 324 : 1567-1569. Hampton JR. (2003) Guidelines – for the obedience of fools and the guidance of wise men. Clinical Medicine 3 : 279-284. Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG et al (1998) Effects of intensive blood pressure lowering and low dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principle results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. HOT study Group. Lancet 351 : 1755-1762 Kordonouri O, Lauterborn R, Deiss D (2002) Lipohypertrophy in young patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 25 : 634. Lovell HG (2000) Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in normotensive diabetic patients with microalbuminuria. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev 2, CD002183. Morris AD, Boyle DIR, McMahon AD (1997) Adherence to insulin treatment, glycaemic control and ketoacidosis in insulin-dependent diabetes. Lancet 350 : 1505-10 National Institute for Clinical Excellence (2002) Management of type 2 diabetes. Renal disease – prevention and early management . NICE, London. National Institute for Clinical Excellence (2002a ) Guidance on the use of long acting analogues for the treatment of diabetes – Insulin Glargine . NICE, London. National Prescribing Centre (2003) Supplementary Prescribing: A resource to help health care professionals to understand the framework and opportunities. National Prescribing Centre, Liverpool. Neighbour R (1987) The inner consultation: how to develop an effective and intuitive consulting style. Kluwer Academic Publisher, Lancaster. Nursing and Midwifery Council (2002) Code of professional conduct. Nursing and Midwifery Council, London. Pendleton D, Schofield T, Tate P, Havelock P (2003) T he new consultation developing doctor-patient communication. Oxford University Press, Oxford. Ramsay LE, Williams B, Johnston GD et al (1999) British Hypertension Society guidelines for hypertension management 1999: summary. BMJ 319 : 630-635 Teft G (2002) Lipohypertrophy: patient awareness and implications for practice. Journal of Diabetes Nursing 6 : 943-950 UKPDS Group (1998) Tight blood pressure control and the risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes. BMJ 317 : 713-20l

Latest news: Antidiabetes drugs and renal outcomes; undiagnosed diabetes; and prevention of diabetic maculopathy

Ageing well with diabetes, improving care for people experiencing homelessness with diabetes, prevention of diabetic maculopathy: trial of oral medication begins, analysis reveals extent of undiagnosed type 2 diabetes, assessing self-efficacy among jordanians with type 1 diabetes, diabetes prehabilitation programme.

Developments that will impact your practice.

Su Down reflects on care for people with diabetes as they age.

Helping homeless adults to overcome the challenges of managing their condition.

16 Apr 2024

Man becomes world’s first recipient of trial drug for diabetic sight loss.

12 Apr 2024

Sign up to all DiabetesontheNet journals

- CPD Learning

- Diabetes & Primary Care

- Diabetes Care for Children & Young People

- The Diabetic Foot Journal

- Diabetes Digest

Useful information

- Terms and conditions

- Privacy policy

- Editorial policies and ethics

By clicking ‘Subscribe’, you are agreeing that DiabetesontheNet.com are able to email you periodic newsletters. You may unsubscribe from these at any time. Your info is safe with us and we will never sell or trade your details. For information please review our Privacy Policy .

Are you a healthcare professional? This website is for healthcare professionals only. To continue, please confirm that you are a healthcare professional below.

We use cookies responsibly to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you continue without changing your browser settings, we’ll assume that you are happy to receive all cookies on this website. Read about how we use cookies .

Implementing nurse prescribing: a case study in diabetes

Affiliation.

- 1 Division of Health and Social Care, University of Surrey, UK. [email protected]

- PMID: 20423387

- DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05212.x

Aim: This paper is a report of a study exploring the views of nurses and team members on the implementation of nurse prescribing in diabetes services.

Background: Nurse prescribing is adopted as a means of improving service efficiency, particularly where demand outstretches resources. Although factors that support nurse prescribing have been identified, it is not known how these function within specific contexts. This is important as its uptake and use varies according to mode of prescribing and area of practice.

Method: A case study was undertaken in nine practice settings across England where nurses prescribed medicines for patients with diabetes. Thematic analysis was conducted on qualitative data from 31 semi-structured interviews undertaken between 2007 and 2008. Participants were qualified nurse prescribers, administrative staff, physicians and non-nurse prescribers.

Findings: Nurses prescribed more often following the expansion of nurse independent prescribing rights in 2006. Initial implementation problems had been resolved and few current problems were reported. As nurses' roles were well-established, no major alterations to service provision were required to implement nurse prescribing. Access to formal and informal resources for support and training were available. Participants were accepting and supportive of this initiative to improve the efficiency of diabetes services.

Conclusion: The main factors that promoted implementation of nurse prescribing in this setting were the ability to prescribe independently, acceptance of the prescribing role, good working relationships between doctors and nurses, and sound organizational and interpersonal support. The history of established nursing roles in diabetes care, and increasing service demand, meant that these diabetes services were primed to assimilate nurse prescribing.

Publication types

- Multicenter Study

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Attitude of Health Personnel*

- Diabetes Mellitus / drug therapy*

- Drug Prescriptions / nursing*

- Interprofessional Relations

- Nurse Practitioners / psychology

- Nurse's Role / psychology*

- Practice Patterns, Nurses'*

- Surveys and Questionnaires

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The following case study illustrates the clinical role of advanced practice nurses in the management of a patient with type 2 diabetes. ... C-ANP, CDE, is associate director and an adult nurse practitioner at the Yale Diabetes Center, Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism, at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

Diabetes Case Study in Mentorship for Nurse Practitioners. chronic care clinical topics diabetes endocrine mentorship real world topics Jan 18, 2022. So many new grads are most worried about building their clinical knowledge base-- for good reason! But it's one thing to prepare for clinical topics-- researching algorithms, choosing the best ...

Nurse Practitioner in Ambulatory Care Medicine at the Panda Medical Center in Atlanta, GA. ... Patients were recruited and selected for the study from the diabetes registry by GCR or were directly referred to her by the patients' PCP. ... Closing the gap: effect of diabetes case management on glycemic control among low-income ethnic minority ...

Diabetes affects more than 37 million Americans, which is about 11% of the population. Approximately 90-95% of people with diabetes have Type 2 diabetes (T2D), and people living with T2D are increasingly cared for by nurse practitioners (NPs). On today's podcast we are joined by NPs Drs. Shannon Idzik and Kathryn Evans-Kreider to discuss case studies of commonly encountered issues in the ...

A role delineation study for clinical nurse specialists, nurse practitioners, RDs, and registered pharmacists,4 conducted in 2000 by the American Nurses Credentialing Center, reported equal findings among all four groups for the skills used to identify pathophysiology, analyze diagnostic tests, and list problems. Assessment for medical ...

This accredited podcast is the 6th and final module in the Clinical Advantage Bootcamp: Type 2 Diabetes Management Certificate for Nurse Practitioners. Listen in as NP diabetes experts Drs. Kathryn Kreider and Shannon Idzik discuss case studies of commonly encountered clinical scenarios of patients living with type 2 diabetes.

Abstract. New-onset type 1 diabetes most frequently presents with diabetic ketoacidosis in young patients. A subset of patients with autoimmune type 1 diabetes may present with a slower progression to insulin deficiency and are frequently misdiagnosed with type 2 diabetes. Clinicians should screen for type 1 diabetes in patients who present ...

The American Diabetes Association (ADA) " Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2018 " recommends a patient-centered, team-based approach to caring for patients with diabetes. Whether a primary care provider is a physician, NP or PA, a treatment plan's success is dependent upon a collaborative team and an informed, activated patient.

Only half of people with diabetes achieve the American Diabetes Association (ADA) general A1C goal of <7.0% (1,2).Twenty-eight percent of people with diabetes have A1C levels >8.0%, and 16% have levels >9.0% ().Risk factors for the latter are a long duration of diabetes, infrequent office visits, and insulin therapy ().Only one-fourth of patients with A1C levels >9.0% are able to lower level ...