Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Building New Course Structures

6 Teaching Undergraduate History: A Problem-Based Approach

Robert K. Poch and Eskender Yousuf

problem solving, historical thinking skills, learning assessment

Introduction

Among the challenges that faculty encounter is facilitating active engagement with their discipline within classrooms of diverse undergraduate students (Calder, 2006; Rendon, 2009). We face this challenge regularly when teaching history. Within a mostly lecture-based format, it is easy to deny students opportunities to engage the discipline as historians.

While we concentrate primarily on the discipline of history, this approach can be applied within other disciplines where the aim is to provide diverse undergraduate students with the opportunity to “do” the work of those disciplines and find personal connection within them. Historians discover and use primary source documents, confront vexing contextual and interpretational problems, experience the diverse perspectives of peers, and so too can students. For many faculty, the temptation in undergraduate survey courses is to place full emphasis on content coverage and to ignore or minimize development of discipline-based skills (Calder, 2006; Sipress and Voelker, 2009). This produces poor results if our instructional goals include providing a more genuine experience with our discipline, developing analytic skills, and engaging students meaningfully (Weimer 2002). When students are passive recipients of disciplinary information with no apparent connection to themselves, they withdraw intellectually and emotionally (Freire 1970; Langer 1997).

However, it is possible for highly diverse students to experience the dynamic nature of disciplines such as history by “doing” – that is, by actively developing the skills and engaging the processes and problems involved in being a practitioner of the discipline (Sipress and Voelker, 2009; Weimer, 2002). This can happen in large and small classes and also in survey courses. We want students to encounter history as historians. We also want them to experience the excitement of historical discovery and personal meaning-making that first drew us into the work. In doing so, students also learn and retain substantive course content.

We focus below on a “problem-based” approach to teaching and learning history where students are active disciplinary practitioners engaged in addressing problem topics of relevance and connection to their diverse lives. In doing so, the following questions are addressed:

- What are some of the core elements of historical inquiry? What do skilled historians actually do?

- What actions encourage students from different cultural and disciplinary backgrounds to engage the core elements of historical inquiry as practitioners?

- How can course pedagogy, assignments, and assessments become consistent with what skilled historians do and foster student engagement?

- How can the results of these efforts be assessed? What are some of the assessment results from using a problem-based approach to learning history?

While we concentrate primarily on the discipline of history, this approach can be applied within other disciplines where the aim is to provide diverse undergraduate students with the opportunity to “do” the work of those disciplines and find personal connection within them (Gurung, Chick, and Haynie, 2009).

Identifying and Using Core Elements of Historical Inquiry

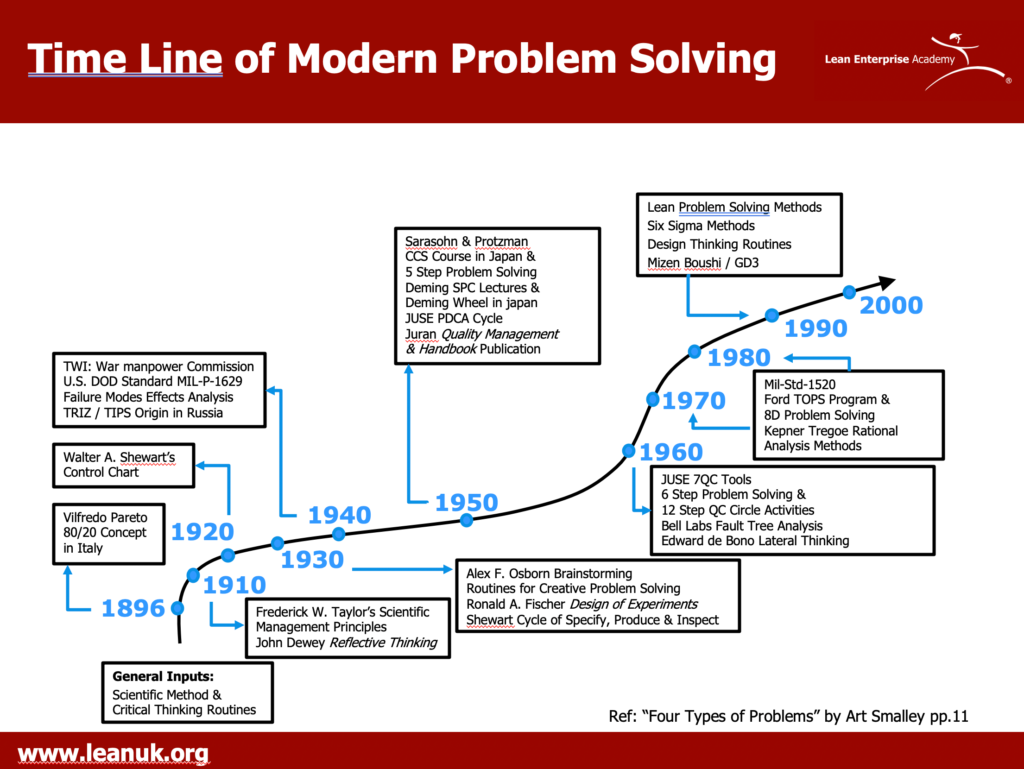

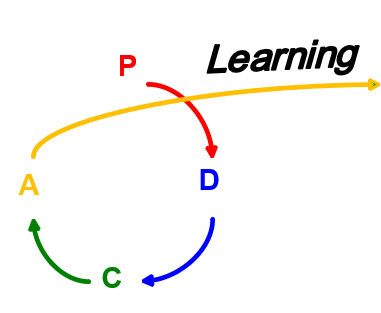

In creating learning environments where students become historians, it is necessary to consider what it is that historians do and what skills are necessary to be practitioners of the discipline. In a macro sense, many historians describe their work as problem solving guided by active questioning (Elton, 1967; Fischer, 1970; Marius and Page, 2005; Nevins, 1963). That is, questions are posed; sources and facts are collected, critically read, contextualized, and organized; and, an interpretation of the past is formed while recognizing that the complexities of history defy easy explanations (Ayers, 2006; Commager, 1965; Wineburg, 1991, 1999). Whenever possible, historians utilize primary sources to form their own interpretations rather than relying mostly on the interpretations of other historians.

Historians are regularly challenged to analyze, contextualize, and interpret the past from incomplete disparate sources. Such actions require a series of more discrete skills including the critical evaluation, interpretation, and communication of evidence; the detection of bias; and careful consideration of historical causation (Ayers, 2005; Barzun and Graff, 1977; Bloch, 1953; Carr, 1961; Commager, 1965; Elton, 1967; Evans, 1999; Fischer, 1970; Lerner, 1997; Nevins, 1963; Wood, 2008). These skills are expressed concisely as the “5Cs” of historical thinking: “change over time, causality, context, complexity, and contingency” (Andrews and Burke, 2007, 1).

Through using the 5Cs, students become increasingly aware of how much can change over time – such as political systems, landscapes, and social values – while, simultaneously, acknowledging retention of strong elements of the past such as holidays and the rituals surrounding them. Further, once developed through classroom engagement with historical sources, the elements of causality, context, complexity, and contingency enable students to identify and appreciate the incomplete nature of historical records and the intricate, simultaneous, and broad scale human interactions and competing interests in history (Ayers, 2006; Nevins, 1963; Wood, 2008). The awareness of complexity causes professional historians and students to probe more deeply into explanations of causality and to reject simplistic reasoning.

To have students engage history problems in a manner that is relevant and meaningful, it is necessary to also think carefully about how to invite students and their interests into the process of historical inquiry. While engineering, mathematics, physics and accounting are experienced as real, relevant, and practical, history is not experienced that way. Students often encounter it as an abstruse, fact-laden, memorization-based, irrelevant, impersonal discipline. We must, therefore, address how to engage students in being practitioners of historical inquiry and interpretation. These are some of the key components of the real work of historians and the historical reasoning used to create interpretations of the past. In working with undergraduate students – some of whom just graduated from high school – the 5Cs are a useful, understandable, and easy to remember toolset for engaging historical inquiry. With these parts of the work of historians and historical thinking in mind, it is possible to design classroom experiences that bring students into the dynamic nature of this work and its associated challenges. Students can then experience the discipline of history more fully and also learn how to create their own historical meaning from available sources (Sipress and Voelker, 2009). These components of historical thinking help to form the “history problems” that we utilize in our U.S. history classroom and which we describe further below.

However, to have students engage history problems in a manner that is relevant and meaningful, it is necessary to also think carefully about how to invite students and their interests into the process of historical inquiry. While engineering, mathematics, physics and accounting are experienced as real, relevant, and practical, history is not experienced that way. Students often encounter it as an abstruse, fact-laden, memorization-based, irrelevant, impersonal discipline. We must, therefore, address how to engage students in being practitioners of historical inquiry and interpretation.

Engaging Students in Core Elements of Historical Inquiry as Practitioners

The invitation to participate in our class, “America’s Past and Present: Multicultural Perspectives,” is underscored by bringing students into direct interaction with historical thinking skills, primary source materials that are reflective of multiple cultures on the American landscape, and with complex historical issues and problems that invite students to interpret history with their own voices rather than having a textbook or the instructor be the sole interpretive voices. We want students to gain more elegant and inclusive views of history that expose the complex dynamics between people over time and which stimulate curiosity about how life was experienced and interpreted by different diverse populations. This is enabled in part by the diversity of our students. The multiple complexities of persons in the past are reflected in our students. As observed by Lee, Poch, Shaw, and Williams (2012),

“…we have observed our institution’s student population become increasingly diverse in terms of racial and ethnic demographics. Historically, generalized categories of racial and ethnic identity have become more diffuse and complex. We are also more mindful of the often less visible forms of difference that are present in any learning environment, such as socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, religion, disability, and many others”

As students engage each other in class and discover how their classmates form different historical interpretations based in part on their different lived experiences, it stimulates and reinforces an understanding of the different perspectives and lived experiences of persons throughout history.

To better ensure the relevance of the history problems to diverse student interests, students are asked on the first day of the course what part of U.S. history between the Civil War and present time is of greatest interest to them. While some students do not know how to answer such a question at first, many others have some notion of their interests. Examples of these student responses from spring semester 2015 are as follows:

- World War II

- U.S. Civil Rights movements (including the role of youth in such movements)

- Vietnam War

- The Great Depression

- 9/11 and its effect on the world

- Other countries and perceptions of the U.S.

- Native Americans and Tribes

- Civil War & differing economies

When we, as instructors, are responsive to such interests, students more fully engage with the topics and are willing to invest the energy to do the challenging work of historical meaning-making using disciplinary thinking skills. These interests are invaluable in making the course ours – that is, a shared experience of historical investigation that reflects mutual interests rather than those of the instructor alone. It is a powerful opportunity to communicate to students at the beginning of the course that the instructors are engaged co-investigators of historical topics that the students suggest and that student interests are of great value. We use student historical interests to create substantive class discussion questions, short reading and writing assignments, and further engagement with historical thinking skills through lengthier history problems that come later in the semester. While assembling sources related to the interests, we spend the first three to four weeks of the course introducing and practicing the 5Cs of historical thinking. Initial reading and writing assignments selected before the course starts enable students to begin the process of understanding, recognizing, and using context, causality, complexity, change and continuity over time, and contingency. These historical thinking skills are then used to explore more deeply and intentionally the historical topics that students suggest. In doing so, student interests become integrated and useful parts of the course experience.

Students also tell us that they want to explore historical themes and issues that are not commonly approached in historical texts or rooted in fact memorization. For example, one student expressed in a topical interest survey that she wanted “…to learn the truth about history. The real original text. I want to find it and research it. Interest in causality and what caused all the events in history to happen? WHYYY! The reason things went down the way they did!” Students express that they want to explore the meaning and use of racism, the rise of feminism, and the perspectives of other nations whose histories intersect with those of the United States. They want to do so in a way that engages history through interesting questions full of encounters with ordinary people who experienced the past in powerful but mostly unknown ways. When we, as instructors, are responsive to such interests, students more fully engage with the topics and are willing to invest the energy to do the challenging work of historical meaning-making using disciplinary thinking skills.

Making Pedagogy, Assignments, and Assessments Consistent with what Historians Actually Do

Engaging students as historians takes careful thought and planning. Core elements of course design are important parts of this work. The course curriculum must provide space for the development of student evaluative and interpretive skills. This often comes with winnowing some course content as traditionally delivered through lengthy lectures (Calder, 2006). The process of winnowing involved using part of a summer break to critically review course materials to identify where unnecessary content was located that cluttered class time and reduced the capacity to develop student historical thinking skills. For example, a discussion of Civil War medicine and pro- and anti-U.S. imperialist arguments were removed given that they were peripheral to more important course themes. Further, those subjects tended to lead to more lecturing rather than active discussion. Rendon (1993) observed that “…many culturally diverse students do not learn best through lecture. Instead, we should focus on collaborative learning and dialogue that promote critical thinking, interpretation and diversity of opinion” (10).

Students can mine rich primary sources of the period as guided by research questions collaboratively developed by students and the instructor. Lectures are balanced with skill-building by doing – actively engaging students in learning how to develop researchable questions, engaging primary and secondary texts with critical lenses, forming interpretations from available evidence, and presenting results. Further, significant thought must be invested in designing course assignments and resources that enable skill development to occur and be assessed. Assessments must be constructed to evaluate student work in a manner consistent with skill development expectations. Class time invested in developing the foundational skills used within the discipline is necessary given that “…history teachers cannot simply present students with documents, tell them what to do, and then expect magical gains in the development of students’ historical sense. Much more elaborate and carefully thought out ‘scaffolding’ is needed to realize the potential of this approach” (Calder et al., 2002, 59).

This approach has significant student developmental implications. It may involve moving students and the course structure away from a dualistic form of learning history where questions are framed in terms of right and wrong response outcomes and there is strong dependency upon the instructor. Instead, there will be movement toward a course design wherein students are met with formulating questions within a course-related area of personal historical interest that has interpretive complexities associated within it (Donald, 2002, 3; Evans et al, 2010).

For example, rather than presenting students with a course design that asks them to identify within an exam three major outcomes of Reconstruction after the U.S. Civil War from lecture notes, students can experience the real problems of Reconstruction in depth by reading conflicting newspaper accounts in the North and the South regarding the political enfranchisement of African American men and the political balances of power that were at play (Langer, 1989). Rather than searching secondary and tertiary sources (such as many textbooks and lectures) alone for such information, students can mine rich primary sources of the period as guided by research questions collaboratively developed by students and the instructor. One research question that was developed in this manner focused on the tactics that some southern states utilized to stymie the voting capacity of black males following passage of the Fifteenth Amendment. In response, students were able to find and analyze different literacy tests for voting (the class even tried taking some of the tests which produced a high failure rate) and also details on the administration of poll taxes.

Such collaboration and student interpretive responsibilities can lead to movement from what psychologist Ellen Langer refers to as “mindlessness” wherein students are stuck with rote memorization and the search for the “right” answer rather than experiencing the rich contexts and possibilities that exist as part of the act of discovering and making meaning within disciplines (Langer, 1997). Langer notes that, “In math, teaching for understanding involves teaching students to think about what a problem means and to look for multiple solutions. Studies have confirmed that science is better taught through hands-on research and discovery than through memorization alone. In English, teaching for understanding means emphasizing the process of writing and exploring literature rather than memorizing grammar rules and doing drills. Understanding is encouraged in history by turning students into junior historians” (Langer, 1997, 71, 72). It is in that spirit that we developed history problems.

History Problems

“As an interpretive historian using the primary source readings that are provided in this problem, how do you define Jim Crow?” This question, which seems deceptively simple at first, quickly exposes the complexities of Jim Crow as a comprehensive system within American society that touched every aspect of life. Each history problem is comprised of three essential parts: an introduction to the problem with concise contextual information; open-ended problem questions designed to provide students with interpretive space to utilize their voice and perspectives (rather than the instructor’s voice or that of the textbook); and a set of primary source materials that reflect diverse authors and views. Students are given three history problems throughout the semester and they have approximately four weeks to complete them given the complexity of the readings. Although there is no required page length for the problem responses, students often write seven pages or more for each problem. The history problems used during the Spring 2015 semester were based on student interests expressed at the beginning of the semester and involved the following topics: “The challenges of Jim Crow and the dynamics found within it;” “’Equal protection under the law:’ The challenges of separate but equal – The struggle for Brown v. Board of Education ;” and, “September 11, 2001.”

The history problem questions provide students with the ability to create responses based on their own interpretation of the material. The questions replicate real challenges and problems for historians that are consistent with the 5Cs of historical thinking that we use in class. Some questions expose students to the complexities of powerful systems of racial oppression such as Jim Crow. Other questions focus on establishing context or examining change over time. For example, in the problem examining Jim Crow, students were asked the following: “As an interpretive historian using the primary source readings that are provided in this problem, how do you define Jim Crow?” This question, which seems deceptively simple at first, quickly exposes the complexities of Jim Crow as a comprehensive system within American society that touched every aspect of life.

To assist in developing a definition of Jim Crow, the history problem packet includes a variety of primary sources that include memoirs, excerpts from scholarly books and novels, and a 1949 travel guide for African American motorists. Within this particular problem packet, the sources included pieces from W.E.B. Dubois’ The Souls of Black Folk (1903); Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (1952); John Hope Franklin’s autobiography, Mirror to America (2005); Howard Thurman’s The Luminous Darkness: A Personal Interpretation of the Anatomy of Segregation and the Ground of Hope (1965); Richard Wright’s Uncle Tom’s Children (1940); and, The Negro Motorist Green Book (1949). The Green Book was published to provide African American travelers with “…information that will keep him from running into difficulties, embarrassments and to make his trips more enjoyable” (1). These sources provided different views of and experiences with Jim Crow and, unlike a textbook, did not provide the definition and interpretation of Jim Crow for the students. Instead, the students worked with the different texts, situated them contextually in their particular time and place and with consideration of who wrote them, and gradually developed their own definition of Jim Crow. Further, the sources spanned a number of decades so that some consideration could be given to change over time in addition to complexity. The sources worked well in providing multiple perspectives of how Jim Crow, as a system, affected different parts of life and also a sense of the varieties of materials that historians use.

The same history problem also asked students to consider how the sources in the packet related to any prior readings we had used in the course (such as Frederick Douglass’ 1865 speech, “What the Black Man Wants”), so that students could further analyze and gain familiarity with context, change over time, complexity, contingency, and causality. Douglass’ speech was useful not only as an earlier expression of the challenges and contradictions that Jim Crow created within a nation that professed freedom and democracy, but also served as a source to explore the challenging concept of contingency. By expressing how black men wanted political participation through receipt of the right to vote and full recognition for their intellectual capacity to be informed contributors to democracy, Douglass’ speech highlighted contingencies necessary for breaking explicit bonds of enslavement and more diffuse societal systems of oppression. These varied course and problem-based primary sources enabled students to make complex connections between forms of evidence and further solidified historical thinking skills as expressed within the 5Cs. Providing approximately four weeks to work with each history problem gave plenty of in-class time to further discuss the sources, the context of the sources, and to practice the skills necessary to utilize them effectively.

Assessing the Results of Using a Problem-Based Approach to Learning History

We utilized several forms of assessment to evaluate the problem-based approach to learning history: 1) the evaluation of student written responses to history problems, 2) individual interviews with students, and, 3) an independently conducted end-of-semester student survey. In each assessment approach, it was important that student voices were prominent and listened to attentively (Patton, 1980). Each of these assessment forms is discussed below.

Written responses to history problems

Student written responses to the four history problems were evaluated carefully for progressive use of the elements of historical thinking. Each of the papers went through two evaluative reviews – one by the course teaching assistant and the other by the primary instructor. The papers were scored on a standard A-F grading scale and were preceded by smaller writing assignments that practiced discrete elements of five identified historical thinking skills. For example, the Frederick Douglass speech, “What the Black Man Wants,” was used early in the semester in part so students could practice establishing and expressing context and recognizing some elements of contingency. This was done with multiple other pieces of short reading and writing exercises that involved the voices and writing of diverse speakers and authors. With this practice experience in place, students could move with greater confidence in addressing contextual issues in the first history problem and those that followed. The papers were also useful in assessing student command or struggle with certain components of historical thinking. We discovered in multiple early papers that students did not fully understand the idea of contingency and, in response, were able to spend more time discussing and practicing it in class.

Toward the end of the semester as students worked with perhaps the most challenging history problem involving the September 11, 2001 attacks, we could detect that students were engaging in far more sophisticated historical reasoning and explicit use of historical thinking skills. For example, one student, a freshman, having studied the presence and role of the United States in the Middle East since the early twentieth-century (using maps, documents, interviews, reports, and political cartoons provided in the fourth history problem), constructed a complex contextual background in her written response to one set of the problem questions (“Using information from our class sessions and the materials provided within this problem packet, describe the relationships that existed and some of the events that occurred between the United States and the ‘Middle East’ region prior to 9/11. With these sources in mind, what are some of the possible motives for the 9/11 attack?”). She responded in part in her introduction,

The events of September 11th, 2001 came as a shock to millions of American citizens; however, a complex history of rocky foreign relations combined with the struggles regarding religion and government in the ‘Middle East’ suggest that the attack was only one part of several interconnected issues. As we examine the context of the events surrounding the 9/11 attacks, the complexity of the United States’ position in world affairs, the major causes leading up to the attack, and contingency of other nations’ histories on our own, we can begin to analyze the affect that each of these has had on the aftermath of 9/11 over time… [the] ten to fifteen years before the attacks on the Twin Towers… show a deeply complex relationship between different nations. While the Saudi Arabian government aided the United States [in the Gulf War by providing a U.S. military staging ground along the border with Kuwait] there were other entities such as Iraq that were pitted against the United States, resulting in conflict between the nations in that area regarding involvement of the United States. To add to this complexity is the idea of a theocracy and questions on how to rule a nation when military forces within those nations do not share the political philosophy or religious beliefs of those nations.

In this brief excerpt which was supported by lengthier supporting text and examples, we could easily detect the use of historical thinking skills (some of which were explicitly mentioned), including greater recognition of the deep complexities that long preceded the events of 9/11.

The written responses to the history problem questions were returned to the students with evaluative comments that served, in part, to prepare students for individual meetings with the course instructor and the graduate research assistant. With highly diverse students from different nations, it was important to provide different opportunities for the students to express how they approached the problems that extended beyond their written responses.

Individual meetings with students about the history problems

Individual student interviews were conducted on two of the problem set essays (history problems one and three). Each student was given the opportunity to schedule a conversation with us to discuss their responses and to further sharpen their historical thinking skills based on the 5Cs. During these meetings, the students could gain additional points (but no subtraction of points) by further clarifying their written responses and the processes that they used to construct them. The meeting questions were provided to each student in advance and included: Where did you encounter the greatest challenges in responding to this history problem? How did you approach the challenges? What do you believe you learned through engaging in this history problem? An opening question was designed to further probe each student’s writing by asking: “We found some engaging interpretations within your paper [if this was truthful] and also some places where we would like to know more. Can you further describe [this was customized for each student paper]….” The questions presented opportunities for students to further explain their own interpretations and how they approached the problems over time. Through the questions, students reflected on and expressed their own historical interpretations in a manner that replicates much of the way that historians utilize peers within their professional communities.

Within the second set of individual meetings on the third history problem, students began to express more of the 5Cs of historical thinking. During the first set of interviews regarding the “Challenges of Jim Crow and the dynamics found within it,” we met individually with twenty-three students who expressed a wide array of historical thinking skills. For example, one student, in expanding upon her interpretation of Jim Crow, remarked that developing her own definition of Jim Crow enabled her to “…go far below the surface to see the complexity of Jim Crow and its relationship to definitions of racism.” Further, the student explained that examining the use of Jim Crow-related art revealed to her the complex strategies of Jim Crow systems of oppression. Another student observed that reading primary source accounts of African Americans who lived within Jim Crow brought forth “contradictions” within the imagery and terms used within Jim Crow such as using ideas of “light” and “visibility” to describe American society while those who lived under the weight of Jim Crow described darkness, shadows, and invisibility. Within these comments, and many others, we observed students expressing different elements of historical thinking including complexity (very explicitly), as well as change over time, and causality as students considered and described the structures of Jim Crow messaging and how the messaging was delivered in different ways during specific spans of time.

Within the second set of individual meetings on the third history problem, students began to express more of the 5Cs of historical thinking. We used a slightly modified set of questions that included: Did you feel that you were able to utilize any particular historical thinking skills in this problem? Students commented more extensively and easily about historical thinking skills and demonstrated within their papers greater complexity in historical thinking. For example, one student expressed complex differences in how African American’s responded to racial oppression over time. She interpreted primary sources in the first history problem as being “defensive in nature – how persons responded or protected themselves within the Jim Crow system” whereas in the third history problem on the legal strategies that African American attorneys used to eventually prevail in the Brown v. Board of Education decision, the strategy was “more offensive in nature in that it showed black persons taking back their rights and being more confident in doing so.” This student, and others, expressed greater awareness and mastery of complexity, causality, and change over time in their interpretations of primary historical source materials.

Independently conducted end-of-semester student survey

At the request of the instructor, a grant-supported survey was developed and given to students in the history course at the very end of spring semester 2015. Among those who responded to the survey (50% of a class of 24 first-year students where this problem-based approach was fully implemented), the following are representative of their responses:

Question: What parts of the course were particularly effective for you in developing historical thinking skills and the capacity to be an effective historian? What parts were particularly ineffective?

- “The parts of this course that were effective in developing historical thinking skills were definitely the history problems and also the 5Cs. I learned so much through the history problems that I would have never learned through a test and I will remember the information much better by writing about it in a history problem. I didn’t feel like any part was ineffective.”

- “The history problems were effective because they allowed us to give our own opinion on the matter and we got involved instead of just mindless memorization.”

- “I think that the most effective things that we did in class to develop my historical thinking skills were definitely the problem sets and our class discussions. Both of those two platforms pushed us to think for ourselves and contribute to a larger group discussion. I loved the problem sets because they forced me to think and form my own opinions using the historical thinking skills that we were given.”

- “The history problems really helped me see how contemporary historians actually applied their skills to modern problems.”

Question: Do you believe that you know and can apply the essential elements of historical thinking, as a result of this course? Please explain.

- “Yes, I have already applied it to other classes and feel very comfortable doing it.”

- “Yes, the history problems gave us that opportunity.”

- “I do believe that I could apply the elements of historical thinking into other classes and in my everyday life as a historian. I feel confident that I know the 5Cs of historical thinking and could use them in other situations. They were drilled into us, I won’t forget them.”

- “Yes. I believe that using the 5Cs from the beginning of this course helped me to gain further knowledge and also to help me dig deeper into historical problems and questions.”

- “I definitely feel that this course has aided my skills in critical analysis and historical thinking and I can see how to use these skills in different contexts and subjects besides history.”

Student survey responses found that 1) history thinking elements of the 5C’s gave them a grasp of historical thinking skills; 2) established a process whereby students could formulate their own interpretations of historical sources thereby moving from mindless memorization to mindfulness and, 3) students were able to utilize their own lived experiences and interests as historians engaged in investigating historical problems.

The use of history problems in our course stems from a twofold purpose. First, we want students to experience the discipline of history as actively engaged historians who use primary sources in addressing challenging questions of historical interpretation through use of well-defined historical thinking skills. Second, we want to facilitate personal interaction with the discipline by using sources and stories that are reflective of the diversity of our students and enabling their interpretive voices to emerge and be respected in our assessments of their learning. Through the use of history problems, unlike our past exams, we noticed the disappearance of instructor voice in student interpretations of historical source materials and an increase in deliberate use of the 5Cs of historical thinking: context, change over time, contingency, complexity, and causality. Continued exploration of the use of history problems in developing more focused development of particular historical thinking skills will occur in our future work as will the capacity to assess those skills effectively through combinations of written work and in-person conversational interactions with students.

Andrews, T., & Burke, F. (2007). “What Does it Mean to Think Historically?” Perspectives on History: The Newsmagazine of the American Historical Association 45 (1), 32-35. Washington, DC: American Historical Association.

Ayers, E. L. (2005). What caused the Civil War?: Reflections on the South and southern history. New York: W.W. Norton & Company

Barzun, J., and Graff, H. F. (1977). The modern researcher. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc.

Bloch, M. (1953). The Historian’s Craft. New York: Vintage Books.

Calder, L., Cutler, W. W., & Mills Kelly, T. (2002). “History Lessons: Historians and the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning.” In M. T. Huber & S.P. Morreale (Eds.). Disciplinary styles in the scholarship of teaching and learning: Exploring common ground. (pp. 45-68). Washington, DC: American Association for Higher Education & The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

Calder, L. (2006). “Uncoverage: Toward a Signature Pedagogy for the History Survey.” The Journal of American History, 1358-1370. .

Carr, E. (1961). What is History? New York: Vintage Books.

Commager, H. S. (1965). The nature and the study of history. Columbus, OH: Charles E. Merrill Books, Inc.

Deloria Jr., V., and Wildcat, D. R. (2001). Power and place: Indian education in America. Golden, CO: American Indian Graduate Center and Fulcrum Resources.

Donald, J. G. (2002). Learning to think: Disciplinary perspectives. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Dubois, W.E.B. (1903). The souls of black folk. Chicago: A.C. McClurg and Co.

Ellison, R. (1952). Invisible man. New York: Random House.

Elton, G. R. (1967). The Practice of History. New York: Thomas Y. Cromwell Company.

Evans, N. J., et al (2010). Student Development in College: Theory, Research, and Practice. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sonsn.

Evans, R. J. (1999). In Defense of History. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Fischer, D. H. (1970). Historians’ Fallacies: Toward a Logic of Historical Thought. New York: HarperPerennial.

Franklin, J. H. (2005). Mirror to America. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Penguin Books.

Guring, A.R.; Chick, N. L.; and Haynie, A., eds. (2009). Exploring Signature Pedagogies: Approaches to Teaching Disciplinary Habits of Mind. Reagan Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

Ladson-Billings, G. (Autumn, 1995). “Toward a Theory of Culturally Relevant Pedagogy,” American Educational Research Journal, Vol. 32, No. 3, 465-491.

Langer, E. J. (1989). Mindfulness. New York: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

Langer, E. J. (1997). The Power of Mindful Learning. New York: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

Lerner, G. (1997). Why History Matters. New York: Oxford University Press.

Marius, R., and Page, M. E. (2005). A Short Guide to Writing about History. New York: Pearson Longman.

Nevins, A. (1963). The Gateway to History. Chicago: Quadrangle Books.

Patton, M. Q. (1980). Qualitative Evaluation Methods. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Rendon, L. I. (2009). Sentipensante (Sensing/Thinking) Pedagogy: Educating for Wholeness, Social Justice and Liberation. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

Rendon, L. I. (February 1993). “Validating Culturally Diverse Students.” Paper Presented at the Annual Conference of the Community College Chairs, Phoenix, Arizona.

Sipress, J. M., and Voelker, D. J. (2009). “From Learning History to Doing History.” Exploring Signature Pedagogies: Approaches to Teaching Disciplinary Habits of Mind. Reagan A.R. Guring, Nancy L. Chick, and Aeron Haynie, eds. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

The Negro Motorist Green Book (1949). New York: Victor H. Green & Co., Publishers. Accessed at: http://www.autolife.umd.umich.edu/Race/R_Casestudy/87_135_1736_GreenBk.pdf

Thurman, H. (1965). The Luminous Darkness: A Personal Interpretation of the Anatomy of Segregation and the Ground of Hope. New York: Harper & Row.

Wineburg, S. (1991). “Historical Problem Solving: A Study of the Cognitive Processes

Wineburg, S. (March 1999). “Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts.” The Phi Delta Kappan, vol. 80, No. 7, pp. 488-499.

Weimer, M. (2002). Learner-Centered Teaching: Five Key Changes to Practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Wood, G. (2008). The Purpose of the Past: Reflections on the Uses of History. New York: The Penguin Press.

Wright, R. (1940). Uncle Tom’s Children. New York: Harper & Brothers.

Acknowledgements

Facilitation and evaluation of this project was enabled by the invaluable support and guidance of Ilene Alexander, Jeff Lindgren, and J.D. Walker. We also acknowledge the work and influence of the following excellent undergraduate teaching assistants who, over the last seven years, contributed to the development, implementation, and the strengthening of the problem based approach to teaching and learning: Emily DePalma, Emily McCune, Julianna Ryburn, Jade Beauclair Sandstrom, and Chris Stewart

Innovative Learning and Teaching: Experiments Across the Disciplines Copyright © 2017 by Individual authors is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Our Mission

Defining Authenticity in Historical Problem Solving

At Sammamish High School, we've identified seven key elements of problem-based learning, an approach that drives our comprehensive curriculum. I teach tenth grade history, which puts me in a unique position to describe the key element of authentic problems.

What is an authentic problem in world history? My colleagues and I grappled with this question when we set about to design a problem-based learning (PBL) class for AP World History. We looked enviously at some of our peer disciplines such as biology which we imagined having clear problems for students to work on (they didn't, but that is another blog post).

We consulted a number of sources in research. What did the College Board say? What do the state standards say? We reached out to Walter Parker, the social studies methods instructor at the University of Washington School of Education, to help us clarify our thinking.

We arrived at two ways to think about authentic problems. One I will call the work of historians in the field, and the other was the work of historical actors at the time. We quickly felt a healthy tension between these two ideas.

Living the Decisions

The work of historians involves creating and debating the frameworks for the historical narratives our students use to interpret history. One problem that historians debate is the question of periodization, or how history should be divided chronologically in order to better understand it. We know these chunks of time -- or eras -- by the more familiar labels given them by historians: classical, medieval and modern, to name a few. These debates are highly charged because they are so important in defining what students entering the field should study. For example, should World War I be considered a turning point in world history, or is World War I really a European civil war whose significance as a global turning point diminishes with passing of each decade?

It was exciting to consider that our students would engage in such high-level and rigorous academic thinking. We could think of many meaty questions for them to explore and discuss: What was the legacy of Mongol rule? Is the modern era a time of progress? Even the question, "Is there really such a thing as world history?" However, we wondered, was it realistic to ask students to do the work of historians? Could we prepare them well enough to have these highly abstract but critical conversations? College professors spend years steeping themselves exclusively in their discipline, while our students devote one seventh of their class time to world history. My colleague and I had both engaged students in such debates during our practice, but not in an integrated systematic way.

Our approach to authentic problems came from a different perspective: that of the historical actor and decision-makers. By giving students roles based around a historical problem we could ask them, "What would you do, and why?" This, of course, is nothing new. Teachers have been creating simulations and role-plays to engage their students for generations. We wanted to build a unit or "challenge cycle" around these activities.

Ultimately, we decided that it would be difficult for students to do the work of historians if they had not done the work of historical actors. By "living" the decisions through problem-based simulations, our students would collectively be better prepared to engage in the larger questions that are debated in the discipline of history.

Challenge Cycles

What did this look like in World History? We created challenge cycles based on each of the eras into which the course was divided. Our first attempt at building a PBL challenge cycle took place when we studied the Early Modern Era (1450-1750) and focused on the theme of diplomacy. Students were assigned to empire teams based on their interests, and they played the role of foreign policy advisors. Their mission: to determine how diplomacy could help their empire maintain and expand power. The simulation component culminated in a round of treaty negotiations between empires. We found that while students were energized and came to know their roles deeply, they were not directly engaging in the conversations and debates that historians have.

After we piloted our first PBL units, we built in a day for a debrief discussion explicitly linking the challenge cycle with the authentic questions that historians address. This debrief day also allowed students to drop their simulation roles, which frequently put them in competitive or modestly adversarial relationships with one another. They were free to argue against the position their historical figure would have taken. For example, during our diplomacy challenge debrief, the Ottoman Empire could argue the position of their Spanish archrivals. We also broke down our challenge cycle into components that allowed students to deepen their understanding of their historical actors in relation to others. In our diplomacy challenge, this meant building in a diplomatic reception in which our student diplomats had to toast an empire with which they wanted to engage in trade.

Diplomats and Historians

What kind of comments have we heard from students? Their response has become more positive as we have refined our pilot units. Here is a brief sample from a survey we took on our diplomacy challenge unit:

- "We all were sort of competing, which made us try harder."

- "The reception was super neat."

- "I really enjoyed knowing about my empire, therefore I wanted to learn more about that empire and master it . . . I liked the process: 1st power point, to get to know the empire. 2nd Toast. This process helped me understand the empires. ."

- "Elaborate more on what actually happened instead of the Socratic seminar [debrief] because I would've liked to know more concrete details."

- "Remove the reception (I think this could have been a two-week project)."

After a year of designing and testing the curriculum, we have come to understand that some problems and their components feel more authentic than others. Representatives of the early modern empires were rarely gathered together at one reception, and diplomacy is obviously conducted over a longer period of time with changing players. However, the toasts our student diplomats made at that diplomatic reception would not have been out of place at a White House state dinner (although our students' were briefer), and the skills they used in trying to woo a trading partner were just as real.

As we continue to refine this course of study, the healthy tension between the work of the historian and the work of the actor remains, as does the desire to create a curriculum where students can meaningfully engage in both.

Editor's Note: Visit " Case Study: Reinventing a Public High School with Problem-Based Learning " to stay updated on Edutopia's coverage of Sammamish High School.

Schoolshistory.org.uk

History resources, stories and news. Author: Dan Moorhouse

Teaching History in the 21st century: 5 interactive strategies

“History is boring,” “there are too many dates to memorize,” “why do I care about things that happened such a long time ago?” are just a few of the questions history teachers have to deal with every day. In the 21st century, children have changed, and they need new approaches and teaching strategies. Proving your students that history is far from being boring, you can tailor interactive classes that go beyond manuals and sheets of dates and events. Let’s see five fun, interactive strategies to make history classes educational, entertaining, and engaging!

Adapting History Lessons to Interactive Teaching Principles

According to researchers in education and learning, the primary purpose of contemporary education should focus on student’s independent activity balanced by team activity, an organization of self-learning environments, and innovative and practical training, critical thinking, initiative, and more. Since history is an essential component of education, teachers should make the effort of engaging the students and entice them to understand history rather than memorize it.

To achieve such goals, teachers should rethink their view on history in general and history teaching in special. In this article, we will take a look at a handful of techniques that aim to:

- Encourage student participation in compelling manners;

- Support students to apply critical thinking upon learned events and draw their conclusions;

- Develop cognitive methods of remembering dates and events in a facile, fun, and long-term manner;

- Use teaching methods that capture/hold the student’s attention while pressing them for thinking and answering;

- Work in teams, show initiative and participate in

1. Use Media to Teach and Generate Engagement

One of the essential interactive teaching styles and principles is the use of media and technology in the classroom. The easiest way to keep students engaged in the history class is to watch a movie together. Luckily, enough, Hollywood and the cinema industry does not find history boring – on the contrary, moviemakers exploit significant events and historical periods to educate viewers and thrill them at the same time.

- If you want to teach them about Weimar and Nazi Germany , you have a handful of awarded movies that can elicit questions, debates, critical thinking, emotion, and reaction – the essential elements of interactive teaching: Wizards (1977 animated film filled with social and political commentary), The Pianist, Schindler’s List, and more.

- After viewing such a heartwarming movie, you can engage the class, ask for opinions, and make a life-lasting lesson about the dangers of totalitarianism and the real horrors of the Holocaust.

Depending on the lesson, you can pick a full movie, an animated one, a few episodes from a TV show, a documentary, YouTube videos, and more. All you must to do is make sure the class gets a genuine reaction from the movie. The more debate you elicit, the better they will learn the pieces of history you want them to learn. Before you press the Play button, make sure the movie is age-appropriate. While some make excellent teaching materials, you need to tailor the violence and the emotional burden depending on the kids’ age.

2. Field Trips

You will not be able to take the children out of the classroom every week, but try doing it as often as you can. History seems dry and dull in the lack of physical support. Luckily, you have plenty of museums to visit together with the kids to make your point, emphasize a conclusion, or help them associate abstract notions with real-life examples.

You can also take them a bit farther and organize a day-trip to memorial sites, monuments, ruins, famous buildings and landmarks that tell a particular story.

Afterward, encourage children to work individually or in a team to mix what they learned from the books with what they saw in the field to make a point or sustain an idea.

3. History is an Ongoing, Fascinating Story

Do you know who loves history even more than directors do? Writers! If you have a particular topic you want kids to understand better, connect it with the literature they read (curriculum or not).

- Have fun with The Three Musketeers while you teach a little piece of French history and engage kids in debates to separate fact from fiction;

- Get Gone with the Wind and North and South a go to discuss the American Civil War;

- Discuss the British Regency period through Pride and Prejudice ’s comment on manners, education, marriage, society, relationships, and money during that period;

- Understand the Stone Age and Iron Age by reading the adventures of Conan the Barbarian ; try to draw similarities among the fictional prehistoric world of Robert E. Howard and our planet’s ancient times;

- Always introduce geography (associate places with events makes learning easier) and even invite the Geography teacher for a few interdisciplinary courses.

You can always invite the English teacher to such class so you two can make an interactive, cross-disciplinary course on events, periods, and social/political evolution of cultures and countries. The English teacher will also be happy about it as such mixes will also help kids understand better the literature they study.

4. Reenactments

While it will be a bit difficult to reenact each battle you have to teach in the book, you can try stepping out of the box from time to time. Reading about fighting in history manuals is not fun, but you can have a class of active kids instead of a bored one, by making the battle/event more real.

Pick a handful of kids and challenge them to play some scenes in the textbooks. They can simulate a battle or an event. This way, you will liven up the classroom, give kids a chance to display their acting skills, have a good laugh together, and retain the essential information from the lesson.

After the theatre scene is over, you can quickly engage the entire classroom in the debate, brainstorming sessions, work in pairs, or argumentative presentations of the topic.

5. Gamification

In education, gamification is an essential component – kids learn better and for more extended periods if they play or have fun during the learning process. You have many ways to introduce gamification in any learning environment and teaching session, but we will focus on teaching history while tackling the most dreadful aspect of this class: learning of dates.

Admittedly, learning dates is just teaching months and years. Memorizing dates is fun and easy, said no children ever, so you need to help them. Times in history are critical, obviously, but lists of number strings do not help anyone.

Welcome fun games and calendars! Let us take World War II for example:

Instead of having your kids memorize that World War II started on September 1 st, 1939 with the attack of Germany on Danzig, you can start from a more easy challenge: what significant things happened in history on September the 1st ? Kids will learn that the 1 st of September means not only the beginning of WWII but also its end (the formal surrender of Japan in 1945) while reminding them that on the 1 st of September 1715 ended the most extended rule of any major monarch in Europe (the death of King Louis XIV of France).

- And what was King Louis XIV known best for? What did he do in Europe that deserves our praise? What fiction books or movies have you seen about him? How do you feel about his times’ fashion, manners, politics, religion, and social interactions?

- You get the point – a date can turn into the most fantastic reason for debate, individual essays, teamwork, multi-media usage, reenactments, literature, general culture, and fun;

- Insert as much trivia and fun historical facts when you teach them dates.

This game of dates and calendars triggers logical transfers in between chunks of memory and information. While it is easier to remember that WWII started and ended on the same day, taking precisely six years, kids will have a more streamlined view on history itself (as many things happened in the same time).

You can continue the game by learning about important events taking place during a specific day in history, to make bridges between information and add a few more games into the mix.

- Associate the crucial historical date with an event, fact, an occurrence that has an emotional impact upon children: WWII started and ended on September 1, when I… (insert here something that the child remembers easily);

- Mix historical vital dates with fun dates: September 6, 1620, is the day when The Mayflower departed from Plymouth to sail to America. What fun thing do we celebrate on the same day? Read a Book Day ! Do you know any books about Plymouth?

Keep a day calendar and a fun calendar close. Kids will learn better and, the dream of any history teacher, will remember more historical events after class is over. Integrating different types of information from various fields in a complex narrative helps people retrieve data from their memory and use complex information in problem-solving.

Teaching interactively engages both the teacher and the classroom. Do everybody a favor and have some genuine fun with history, as kids will love it like never before.

Primary History – Great Resources For Teaching Primary History – Knowledge Rich resources that are free – Mozaik3D

User submitted article, thanks Sean.

- ← Edtech for Primary: Mozaik3D

- Using mobile technologies in the history classroom →

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- 37526 Share on Facebook

- 2387 Share on Twitter

- 6886 Share on Pinterest

- 2979 Share on LinkedIn

- 5475 Share on Email

Subscribe to our Free Newsletter, Complete with Exclusive History Content

Thanks, I’m not interested

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Original Language Spotlight

- Alternative and Non-formal Education

- Cognition, Emotion, and Learning

- Curriculum and Pedagogy

- Education and Society

- Education, Change, and Development

- Education, Cultures, and Ethnicities

- Education, Gender, and Sexualities

- Education, Health, and Social Services

- Educational Administration and Leadership

- Educational History

- Educational Politics and Policy

- Educational Purposes and Ideals

- Educational Systems

- Educational Theories and Philosophies

- Globalization, Economics, and Education

- Languages and Literacies

- Professional Learning and Development

- Research and Assessment Methods

- Technology and Education

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Problem solving.

- Richard E. Mayer Richard E. Mayer University of California, Santa Barbara

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.860

- Published online: 30 October 2019

Problem solving refers to cognitive processing directed at achieving a goal when the problem solver does not initially know a solution method. A problem exists when someone has a goal but does not know how to achieve it. Problems can be classified as routine or non-routine, and as well-defined or ill-defined. The major cognitive processes in problem solving are representing, planning, executing, and monitoring. The major kinds of knowledge required for problem solving are facts, concepts, procedures, strategies, and beliefs. The theoretical approaches that have developed over the history of research on problem are associationism, Gestalt, and information processing. Each of these approaches involves fundamental issues in problem solving such as the nature of transfer, insight, and goal-directed heuristics, respectively. Some current research topics in problem solving include decision making, intelligence and creativity, teaching of thinking skills, expert problem solving, analogical reasoning, mathematical and scientific thinking, everyday thinking, and the cognitive neuroscience of problem solving. Common theme concerns the domain specificity of problem solving and a focus on problem solving in authentic contexts.

- problem solving

- decision making

- intelligence

- expert problem solving

- analogical reasoning

- mathematical thinking

- scientific thinking

- everyday thinking

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Education. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 14 May 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|195.158.225.230]

- 195.158.225.230

Character limit 500 /500

A Brief History of Problem-based Learning

- First Online: 01 January 2012

Cite this chapter

- Henk G. Schmidt 5

2603 Accesses

25 Citations

In this chapter, we will describe the emergence of problem-based learning as an approach to higher education, first at McMaster University Faculty of Health Sciences in Canada and then worldwide. Problem-based learning did not appear out of the blue but had several precursors: First in the work of Dewey who established an experimental school at the University of Chicago based on the idea that learning is more interesting if the learner is actively involved in his own learning. The second source of influence was the Case Study Method pioneered at Harvard University in the 1930s of the previous century. And the third source of influence to be described is Jerome Bruner’s “learning by discovery” from which the idea that a problem could be the starting point for learning originated. Problem-based learning has eventually developed into three different strands or “Types,” that agree on the basic elements of the approach but see different goals for it.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

The others were John Evans, first dean of the Faculty of Health Sciences, Jim Anderson, Bill Walsh and J. Fraser Mustard.

What makes the McMaster educational innovation unique is perhaps not the ideas themselves but the daring mix of these ideas. From its inception, the McMaster curriculum featured small-group tutorials, emphasis on self-directed and life-long learning, the use of varied resources in learning, and the integration of biomedical and clinical sciences in the curriculum.

From the descriptions given by Spaulding ( 1991 ) and Mustard et al. ( 1982 ), it is not clear whether John Evans was the sole author of the premises appended under A, or that others contributed as well. Spaulding speaks about a position paper written by dean Evans that played an important role in the early discussions. We have, however, not been able to unearth the original paper in question.

Students knew this better than their tutors. Even in the seventies, when the first author visited McMaster for the first time, there was a hidden curriculum at McMaster, through which students acquired the knowledge deemed necessary to understand the processes, principles and mechanisms involved in health and disease. In addition, at the end of their years of training, just before the licensing examinations, they took a course aimed at “cramming” the necessary information. Nevertheless, for years, McMaster graduates scored below average on these national examinations, which can be attributed to the emphasis on process rather than content. With a shift in emphasis on knowledge during a 1990s curriculum reform, this difference has disappeared.

Antepohl, W., & Herzig, S. (1999). Problem-based learning versus lecture-based learning in a course of basic pharmacology: A controlled, randomized study. Medical Education, 33 (2), 106–113.

Article Google Scholar

Association of American Medical Colleges (2005). Curriculum directory . http://services.aamc.org/currdir/start.cfm . Accessed 18 April 2005.

Barrows, H. S. (1984). A specific, problem-based, self-directed learning method designed to teach medical problem-solving skills, self-learning skills and enhance knowledge retention and recall. In H. G. Schmidt & M. L. De Volder (Eds.), Tutorials in problem-based learning . Assen: Van Gorcum.

Google Scholar

Barrows, H. S., & Mitchell, D. L. M. (1975). An innovative course in undergraduate neuroscience experiment in problem-based learning with problem boxes. British Journal of Medical Education, 9 , 223–230.

Barrows, H. S., & Tamblyn, R. (1980). Problem-based learning: An approach to medical education . New York: Springer.

Barrows, H. S., Neufeld, V. R., Feightner, J. W., & Norman, G. R. (1978). An analysis of the clinical methods of medical students and physicians . Hamilton: McMaster University.

Beckman, M. D. (1972). Evaluating the case method. Educational Forum, 36 (4), 489–497.

Blumberg, P., & Michael, J. A. (1992). Development of self-directed learning behaviors in a partially teacher-directed problem-based learning curriculum. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 4 , 3–8.

Boud, D., & Feletti, G. (1992). The challenge of problem-based learning . London: Kogan-Page.

Bouhuijs, P. A. J., Schmidt, H. G., Snow, R. E., & Wijnen, W. H. F. W. (1978). The Rijksuniversiteit Limburg, Maastricht, the Netherlands: Development of medical education. In F. M. Katz & T. Fülöp (Eds.), Personnel for health care: Case studies of educational programmes (pp. 133–151). Geneva: World Health Organization.

Brown, J. S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18 (1), 32–42.

Bruner, J. S. (1959). Learning and thinking. Harvard Educational Review, 29 , 184–192.

Bruner, J. S. (1961). The act of discovery. Harvard Educational Review, 31 , 21–32.

Bruner, J. S. (1966). Towards a theory of instruction . New York: Norton.

Bruner, J. S., Goodnow, J. J., & Austin, G. A. (1956). A study of thinking . New York: Wiley.

Capon, N., & Kuhn, D. (2004). What’s so good about problem-based learning? Cognition and Instruction, 22 (1), 61–79.

Cohen, E. (1994). Restructuring the classroom: Conditions for productive small groups. Review of Educational Research, 64 , 1–35.

Dahlgren, M. A., & Dahlgren, L. O. (2002). Portraits of PBL: Students’ experiences of the characteristics of problem-based learning in physiotherapy, computer engineering and psychology. Instructional Science, 30 (2), 111–127.

De Grave, W. S., Schmidt, H. G., & Boshuizen, H. P. A. (2001). Effects of problem-based discussion on studying a subsequent text: A randomized trial among first year medical students. Instructional Science, 29 , 33–44.

Dewey, J. (1902). The child and the curriculum . Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Dewey, J. (1929). The quest for certainty . New York: Minton.

Elstein, A. S., Shulman, L. S., & Sprafka, S. A. (1978). Medical problem solving: An analysis of clinical reasoning . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Ertmer, P. A., & Simons, K. D. (2006). Jumping the PBL implementation hurdle: Supporting the efforts of K–12 teachers. The Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-based Learning, 1 (1), 40–54.

Fraser, C. E. (1931). The case method of instruction . New York: McGraw-Hill.

Fyrenius, A., Silen, C., & Wirell, S. (2007). Students’ conceptions of underlying principles in medical physiology: An interview study of medical students’ understanding in a PBL curriculum. Advances in Physiology Education, 31 (4), 364–369.

Gijselaers, W. H., Tempelaar, D. T., Keizer, P. K., Blommaert, J. M., Bernard, E. M., & Kasper, H. (Eds.). (1995). Educational innovation in economics and business education: The case of problem-based learning . Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Grochla, E., & Thom, N. (1975). Fallmethode und Gruppenarbeit in der betriefswirtschaftlichen Hochschulausbildung . Hamburg: Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Hochschuldidaktik.

Hamilton, J. D. (1976). The McMaster curriculum: A critique. British Medical Journal, 1 , 1191–1196.

Hmelo-Silver, C. E. (2004). Problem-based learning: What and how do students learn? Educational Psychology Review, 16 (3), 235–266.

Hobus, P. P. M. (1994). Expertise van huisartsen, praktijkervaring, kennis en diagnostische hypothesevorming (Expertise of family physicians; practical experience, knowledge and the formation of diagnostic hypotheses) . University of Limburg, Maastricht.

Hoffman, K., Hosokawa, M., Blake, R., Headrick, L., & Johnson, G. (2006). Problem-based learning outcomes: Ten years of experience at the University of Missouri-Columbia School of Medicine. Academic Medicine, 81 (7), 617–625.

Juul-Dam, N., Brunner, S., Katzenellenbogen, R., Silverstein, M., & Christakis, D. A. (2001). Does problem-based learning improve residents’ self-directed learning? Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 155 (6), 673–675.

Kaufman, A. (Ed.). (1985). Implementing problem-based medical education: Lessons from successful innovations . New York: Springer.

Kendler, B. S., & Grove, P. A. (2004). Problem-based learning in the biology curriculum. The American Biology Teacher, 66 (5), 348–354.

Khoo, H. E. (2003). Implementation of problem-based learning in Asian medical schools and students’ perceptions of their experience. Medical Education, 37 (5), 401–409.

Loyens, S. M. M., Rikers, R. M. J. P., & Schmidt, H. G. (2007). The impact of students’ conceptions of constructivist assumptions on academic achievement and drop-out. Studies in Higher Education, 32 , 581–602.

Marshall, J. G., Fitzgerald, D., Busby, L., & Heaton, G. (1993). A study of library use in problem-based and traditional medical curricula. Bulletin of the Medical Library Association, 81 (3), 299–305.

Mayer, R. E. (1975). Information processing variables in learning to solve problems. Review of Educational Research, 45 (4), 525–541.

Moust, J. H. C., & Nuy, H. J. (1987). Preparing teachers for a problem-based student-centred law course. Journal of Professional Legal Education, 5 (1), 16–30.

Mustard, J. F., Neufeld, V. R., Walsh, W. J., & Cochran, J. (1982). New trends in health sciences education, research and services: The McMaster experience . New York: Praeger.

Neame, R. L. (1989). Problem-based medical education: The Newcastle approach. In H. G. Schmidt, M. Lipkin, M. De Vries, & J. Greep (Eds.), New directions for medical education: Problem-based learning and community-oriented medical education (pp. 112–146). New York: Springer Verlag.

Neufeld, V. R., & Barrows, H. S. (1974). The “McMaster philosophy”: An approach to medical education. Journal of Medical Education, 49 , 1040–1050.

Neville, A. J., & Norman, G. R. (2007). PBL in the undergraduate MD program at McMaster University: Three iterations in three decades. Academic Medicine, 82 (4), 370–374.

Norman, G. (2005). Research in clinical reasoning: Past history and current trends. Medical Education, 39 (4), 418–427.

Norman, G. R., & Schmidt, H. G. (1992). The psychological basis of problem-based learning – A review of the evidence. Academic Medicine, 67 (9), 557–565.

O’Neill, P. A., Metcalfe, D., & David, T. J. (1999). The core content of the undergraduate curriculum in Manchester. Medical Education, 33 (2), 121–129.

O’Neill, P. A., Morris, J., & Baxter, C. M. (2000). Evaluation of an integrated curriculum using problem-based learning in a clinical environment: The Manchester experience. Medical Education, 34 (3), 222–230.

Ozuah, P. O., Curtis, J., & Stein, R. E. K. (2001). Impact of problem-based learning on residents’ self-directed learning. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 155 (6), 669–672.

Patel, V. L., & Groen, G. J. (1986). Knowledge-based solution strategies in medical reasoning. Cognitive Science, 10 , 91–116.

Plato. (1949). Meno . Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merril.

Rankin, J. A. (1992). Problem-based medical education – Effect on library use. Bulletin of the Medical Library Association, 80 (1), 36–43.

Reynolds, F. (1997). Studying psychology at degree level: Would problem-based learning enhance students’ experiences? Studies in Higher Education, 22 (3), 263–275.

Sanson-Fisher, R. W., & Lynagh, M. C. (2005). Problem-based learning: A dissemination success story? Medical Journal of Australia, 183 , 258–260.

Scardamalia, M., & Bereiter, C. (1991). Higher levels of agency for children in knowledge building: A challenge for the design of new knowledge media. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 1 , 37–68.

Schmidt, H. G. (1982). Activation and restructuring of prior knowledge and their effects on text processing. In A. Flammer & W. Kintsch (Eds.), Discourse processing (pp. 325–338). Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing.

Chapter Google Scholar

Schmidt, H. G. (1983). Problem-based learning: Rationale and description. Medical Education, 17 (1), 11–16.

Schmidt, H. G. (1993). Foundations of problem-based learning – Some explanatory notes. Medical Education, 27 (5), 422–432.

Schmidt, H. G. (2000). Assumptions underlying self-directed learning may be false. Medical Education, 34 (4), 243–245.

Schmidt, H. G., De Grave, W. S., De Volder, M. L., Moust, J. H. C., & Patel, V. L. (1989). Explanatory models in the processing of science text: The role of prior knowledge activation through small-group discussion. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81 (4), 610–619.

Schmidt, H. G., Norman, G. R., & Boshuizen, H. P. A. (1990). A cognitive perspective on medical expertise – Theory and implications. Academic Medicine, 65 (10), 611–621.

Schwartz, D. L., & Bransford, J. D. (1998). A time for telling. Cognition and Instruction, 16 (4), 475–522.

Shin, J. H., Haynes, R. B., & Johnston, M. E. (1993). Effect of problem-based, self-directed undergraduate education on life-long learning. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 148 (6), 969–976.

Shulman, L. S., & Keislar, E. R. (1966). Learning by discovery, a critical appraisal . Chicago: Rand McNally.

Sibley, J. C. (1989). Toward an emphasis on problem-solving in teaching and learning: The McMaster experience. In H. G. Schmidt, M. Lipkin, M. De Vries, & J. Greep (Eds.), New directions for medical education: Problem-based learning and community-oriented medical education (pp. 147–156). New York: Springer Verlag.

Silen, C., & Uhlin, L. (2008). Self-directed learning – A learning issue for students and faculty! Teaching in Higher Education, 13 (4), 461–475. doi: 10.1080/13562510802169756 .

Spaulding, W. B. (1991). Revitalizing medical education. McMaster Medical School, the early years 1965–1974 . Hamilton: B.C. Decker.

Tans, R. W., Schmidt, H. G., Schade-Hoogeveen, B. E. J., & Gijselaers, W. H. (1986). Sturing van het onderwijsleerproces door middel van problemen: Een veldexperiment (guiding the learning process by means of problems: A field experiment). Tijdschrift voor Onderwijsresearch, 11 (1), 38–48.

Tiwari, A., Lai, P., So, M., & Yuen, K. (2006). A comparison of the effects of problem-based learning and lecturing on the development of students’ critical thinking. Medical Education, 40 (6), 547–554.

Toon, P. (1997). Educating doctors, to improve patient care – A choice between self directed learning and sitting in lecture struggling to stay awake. British Medical Journal, 315 (7104), 326–326.

Tosteson, D. C., Adelstein, S. J., & Carver, S. T. (Eds.). (1994). New pathways to medical education: Learning to learn at Harvard Medical School . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Winch, C. (2008). Learning how to learn: A critique. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 42 (3–4), 649–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9752.2008.00644.x .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Erasmus University, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

Henk G. Schmidt

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Henk G. Schmidt .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

woodlands Avenue 9, Singapore, 738964, Singapore

Glen O'Grady

Singapore, Singapore

Elaine H.J. Yew

Woodlands Avenue 9, Singapore, 738964, Singapore

Karen P.L. Goh

Rotterdam, 3062 PA, Netherlands

Appendix A: Basic Premises of the McMaster M.D. Program

These premises arose out of the strong beliefs of the early planners at the McMaster Medical School that we should be innovative and prepared to experiment Mustard et al. ( 1982 ). Dissatisfaction with: traditional course work consisting largely of lectures and laboratory exercises; admission to medical school chiefly on the basis of high grades in science courses; emphasis on achieving high marks in content-oriented examinations; and a tendency to stress teaching while paying little attention to helping students learn, lay behind much of the early thinking.

Premise # 1: A curriculum which is based on biomedical problems, and stresses acquiring knowledge to solve problems, will help to establish a lifelong pattern of questioning, seeking and formulating solutions.

Expressions:

The core curriculum consists of a series of biomedical problems.

Students learn to: identify major issues and questions in problems; hypothesize; seek information; formulate solutions.