- Privacy Policy

Home » Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

Table of Contents

Explanatory Research

Definition :

Explanatory research is a type of research that aims to uncover the underlying causes and relationships between different variables. It seeks to explain why a particular phenomenon occurs and how it relates to other factors.

This type of research is typically used to test hypotheses or theories and to establish cause-and-effect relationships. Explanatory research often involves collecting data through surveys , experiments , or other empirical methods, and then analyzing that data to identify patterns and correlations. The results of explanatory research can provide a better understanding of the factors that contribute to a particular phenomenon and can help inform future research or policy decisions.

Types of Explanatory Research

There are several types of explanatory research, each with its own approach and focus. Some common types include:

Experimental Research

This involves manipulating one or more variables to observe the effect on other variables. It allows researchers to establish a cause-and-effect relationship between variables and is often used in natural and social sciences.

Quasi-experimental Research

This type of research is similar to experimental research but lacks full control over the variables. It is often used in situations where it is difficult or impossible to manipulate certain variables.

Correlational Research

This type of research aims to identify relationships between variables without manipulating them. It involves measuring and analyzing the strength and direction of the relationship between variables.

Case study Research

This involves an in-depth investigation of a specific case or situation. It is often used in social sciences and allows researchers to explore complex phenomena and contexts.

Historical Research

This involves the systematic study of past events and situations to understand their causes and effects. It is often used in fields such as history and sociology.

Survey Research

This involves collecting data from a sample of individuals through structured questionnaires or interviews. It allows researchers to investigate attitudes, behaviors, and opinions.

Explanatory Research Methods

There are several methods that can be used in explanatory research, depending on the research question and the type of data being collected. Some common methods include:

Experiments

In experimental research, researchers manipulate one or more variables to observe their effect on other variables. This allows them to establish a cause-and-effect relationship between the variables.

Surveys are used to collect data from a sample of individuals through structured questionnaires or interviews. This method can be used to investigate attitudes, behaviors, and opinions.

Correlational studies

This method aims to identify relationships between variables without manipulating them. It involves measuring and analyzing the strength and direction of the relationship between variables.

Case studies

Case studies involve an in-depth investigation of a specific case or situation. This method is often used in social sciences and allows researchers to explore complex phenomena and contexts.

Secondary Data Analysis

This method involves analyzing data that has already been collected by other researchers or organizations. It can be useful when primary data collection is not feasible or when additional data is needed to support research findings.

Data Analysis Methods

Explanatory research data analysis methods are used to explore the relationships between variables and to explain how they interact with each other. Here are some common data analysis methods used in explanatory research:

Correlation Analysis

Correlation analysis is used to identify the strength and direction of the relationship between two or more variables. This method is particularly useful when exploring the relationship between quantitative variables.

Regression Analysis

Regression analysis is used to identify the relationship between a dependent variable and one or more independent variables. This method is particularly useful when exploring the relationship between a dependent variable and several predictor variables.

Path Analysis

Path analysis is a method used to examine the direct and indirect relationships between variables. It is particularly useful when exploring complex relationships between variables.

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

SEM is a statistical method used to test and validate theoretical models of the relationships between variables. It is particularly useful when exploring complex models with multiple variables and relationships.

Factor Analysis

Factor analysis is used to identify underlying factors that contribute to the variation in a set of variables. This method is particularly useful when exploring relationships between multiple variables.

Content Analysis

Content analysis is used to analyze qualitative data by identifying themes and patterns in text, images, or other forms of data. This method is particularly useful when exploring the meaning and context of data.

Applications of Explanatory Research

The applications of explanatory research include:

- Social sciences: Explanatory research is commonly used in social sciences to investigate the causes and effects of social phenomena, such as the relationship between poverty and crime, or the impact of social policies on individuals or communities.

- Marketing : Explanatory research can be used in marketing to understand the reasons behind consumer behavior, such as why certain products are preferred over others or why customers choose to purchase from certain brands.

- Healthcare : Explanatory research can be used in healthcare to identify the factors that contribute to disease or illness, as well as the effectiveness of different treatments and interventions.

- Education : Explanatory research can be used in education to investigate the causes of academic achievement or failure, as well as the factors that influence teaching and learning processes.

- Business : Explanatory research can be used in business to understand the factors that contribute to the success or failure of different strategies, as well as the impact of external factors, such as economic or political changes, on business operations.

- Public policy: Explanatory research can be used in public policy to evaluate the effectiveness of policies and programs, as well as to identify the factors that contribute to social problems or inequalities.

Explanatory Research Question

An explanatory research question is a type of research question that seeks to explain the relationship between two or more variables, and to identify the underlying causes of that relationship. The goal of explanatory research is to test hypotheses or theories about the relationship between variables, and to gain a deeper understanding of complex phenomena.

Examples of explanatory research questions include:

- What is the relationship between sleep quality and academic performance among college students, and what factors contribute to this relationship?

- How do environmental factors, such as temperature and humidity, affect the spread of infectious diseases?

- What are the factors that contribute to the success or failure of small businesses in a particular industry, and how do these factors interact with each other?

- How do different teaching strategies impact student engagement and learning outcomes in the classroom?

- What is the relationship between social support and mental health outcomes among individuals with chronic illnesses, and how does this relationship vary across different populations?

Examples of Explanatory Research

Here are a few Real-Time Examples of explanatory research:

- Exploring the factors influencing customer loyalty: A business might conduct explanatory research to determine which factors, such as product quality, customer service, or price, have the greatest impact on customer loyalty. This research could involve collecting data through surveys, interviews, or other means and analyzing it using methods such as correlation or regression analysis.

- Understanding the causes of crime: Law enforcement agencies might conduct explanatory research to identify the factors that contribute to crime in a particular area. This research could involve collecting data on factors such as poverty, unemployment, drug use, and social inequality and analyzing it using methods such as regression analysis or structural equation modeling.

- Investigating the effectiveness of a new medical treatment: Medical researchers might conduct explanatory research to determine whether a new medical treatment is effective and which variables, such as dosage or patient age, are associated with its effectiveness. This research could involve conducting clinical trials and analyzing data using methods such as path analysis or SEM.

- Exploring the impact of social media on mental health : Researchers might conduct explanatory research to determine whether social media use has a positive or negative impact on mental health and which variables, such as frequency of use or type of social media, are associated with mental health outcomes. This research could involve collecting data through surveys or interviews and analyzing it using methods such as factor analysis or content analysis.

When to use Explanatory Research

Here are some situations where explanatory research might be appropriate:

- When exploring a new or complex phenomenon: Explanatory research can be used to understand the mechanisms of a new or complex phenomenon and to identify the variables that are most strongly associated with it.

- When testing a theoretical model: Explanatory research can be used to test a theoretical model of the relationships between variables and to validate or modify the model based on empirical data.

- When identifying the causal relationships between variables: Explanatory research can be used to identify the causal relationships between variables and to determine which variables have the greatest impact on the outcome of interest.

- When conducting program evaluation: Explanatory research can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of a program or intervention and to identify the factors that contribute to its success or failure.

- When making informed decisions: Explanatory research can be used to provide a basis for informed decision-making in business, government, or other contexts by identifying the factors that contribute to a particular outcome.

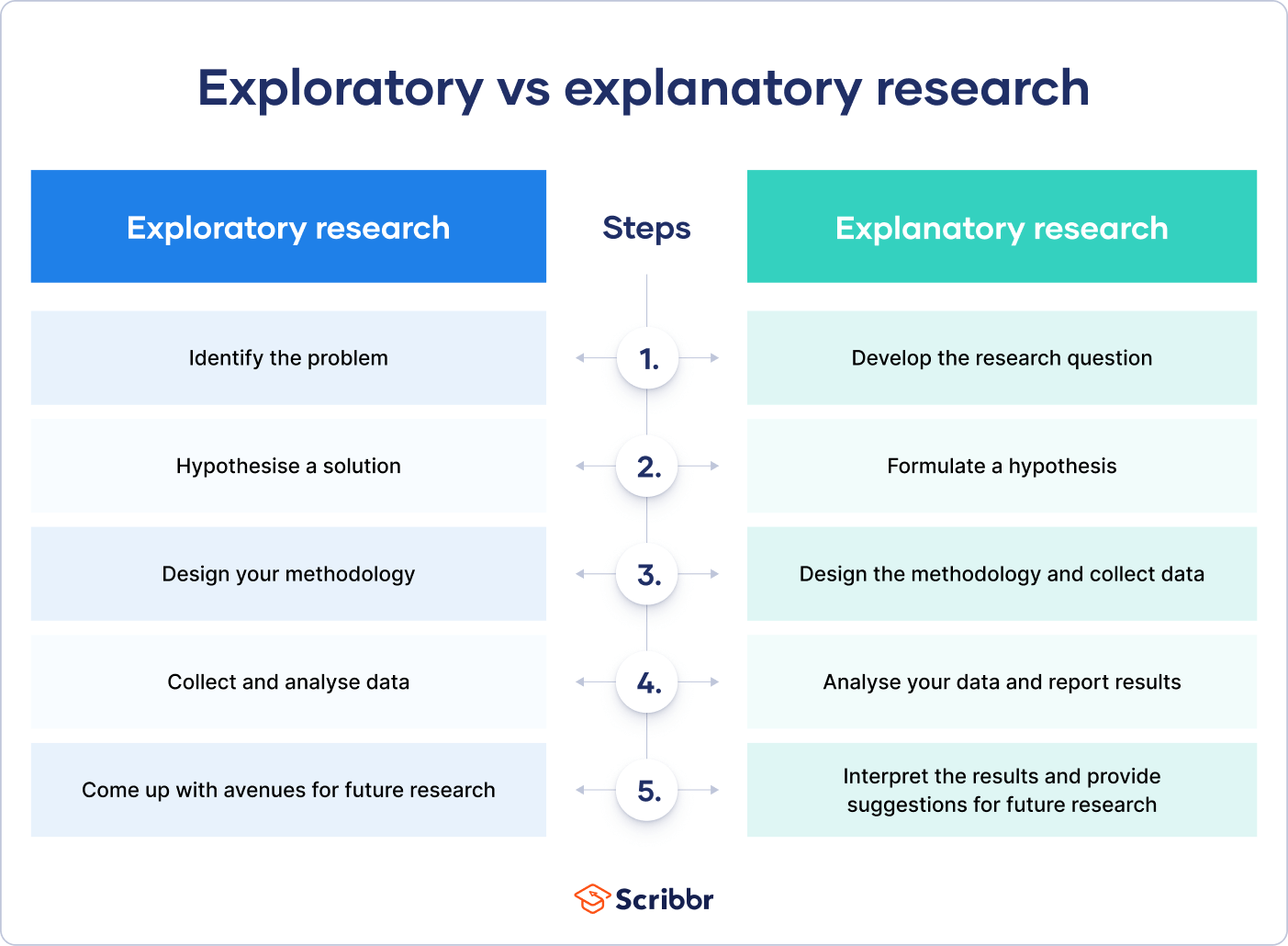

How to Conduct Explanatory Research

Here are the steps to conduct explanatory research:

- Identify the research problem: Clearly define the research question or problem you want to investigate. This should involve identifying the variables that you want to explore, and the potential relationships between them.

- Conduct a literature review: Review existing research on the topic to gain a deeper understanding of the variables and relationships you plan to explore. This can help you develop a hypothesis or research questions to guide your study.

- Develop a research design: Decide on the research design that best suits your study. This may involve collecting data through surveys, interviews, experiments, or observations.

- Collect and analyze data: Collect data from your selected sample and analyze it using appropriate statistical methods to identify any significant relationships between variables.

- Interpret findings: Interpret the results of your analysis in light of your research question or hypothesis. Identify any patterns or relationships between variables, and discuss the implications of your findings for the wider field of study.

- Draw conclusions: Draw conclusions based on your analysis and identify any areas for further research. Make recommendations for future research or policy based on your findings.

Purpose of Explanatory Research

The purpose of explanatory research is to identify and explain the relationships between different variables, as well as to determine the causes of those relationships. This type of research is often used to test hypotheses or theories, and to explore complex phenomena that are not well understood.

Explanatory research can help to answer questions such as “why” and “how” by providing a deeper understanding of the underlying causes and mechanisms of a particular phenomenon. For example, explanatory research can be used to determine the factors that contribute to a particular health condition, or to identify the reasons why certain marketing strategies are more effective than others.

The main purpose of explanatory research is to gain a deeper understanding of a particular phenomenon, with the goal of developing more effective solutions or interventions to address the problem. By identifying the underlying causes and mechanisms of a phenomenon, explanatory research can help to inform decision-making, policy development, and best practices in a wide range of fields, including healthcare, social sciences, business, and education

Advantages of Explanatory Research

Here are some advantages of explanatory research:

- Provides a deeper understanding: Explanatory research aims to uncover the underlying causes and mechanisms of a particular phenomenon, providing a deeper understanding of complex phenomena that is not possible with other research designs.

- Test hypotheses or theories: Explanatory research can be used to test hypotheses or theories by identifying the relationships between variables and determining the causes of those relationships.

- Provides insights for decision-making: Explanatory research can provide insights that can inform decision-making in a wide range of fields, from healthcare to business.

- Can lead to the development of effective solutions: By identifying the underlying causes of a problem, explanatory research can help to develop more effective solutions or interventions to address the problem.

- Can improve the validity of research: By identifying and controlling for potential confounding variables, explanatory research can improve the validity and reliability of research findings.

- Can be used in combination with other research designs : Explanatory research can be used in combination with other research designs, such as exploratory or descriptive research, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon.

Limitations of Explanatory Research

Here are some limitations of explanatory research:

- Limited generalizability: Explanatory research typically involves studying a specific sample, which can limit the generalizability of findings to other populations or settings.

- Time-consuming and resource-intensive: Explanatory research can be time-consuming and resource-intensive, particularly if it involves collecting and analyzing large amounts of data.

- Limited scope: Explanatory research is typically focused on a narrow research question or hypothesis, which can limit its scope in comparison to other research designs such as exploratory or descriptive research.

- Limited control over variables: Explanatory research can be limited by the researcher’s ability to control for all possible variables that may influence the relationship between variables of interest.

- Potential for bias: Explanatory research can be subject to various types of bias, such as selection bias, measurement bias, and recall bias, which can influence the validity of research findings.

- Ethical considerations: Explanatory research may involve the use of invasive or risky procedures, which can raise ethical concerns and require careful consideration of the potential risks and benefits of the study.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Survey Research – Types, Methods, Examples

Experimental Design – Types, Methods, Guide

Types of Case Studies

There are several different types of case studies, as well as several types of subjects of case studies. We will investigate each type in this article.

Different Types of Case Studies

There are several types of case studies, each differing from each other based on the hypothesis and/or thesis to be proved. It is also possible for types of case studies to overlap each other.

Each of the following types of cases can be used in any field or discipline. Whether it is psychology, business or the arts, the type of case study can apply to any field.

Explanatory

The explanatory case study focuses on an explanation for a question or a phenomenon. Basically put, an explanatory case study is 1 + 1 = 2. The results are not up for interpretation.

A case study with a person or group would not be explanatory, as with humans, there will always be variables. There are always small variances that cannot be explained.

However, event case studies can be explanatory. For example, let's say a certain automobile has a series of crashes that are caused by faulty brakes. All of the crashes are a result of brakes not being effective on icy roads.

What kind of case study is explanatory? Think of an example of an explanatory case study that could be done today

When developing the case study, the researcher will explain the crash, and the detailed causes of the brake failure. They will investigate what actions caused the brakes to fail, and what actions could have been taken to prevent the failure.

Other car companies could then use this case study to better understand what makes brakes fail. When designing safer products, looking to past failures is an excellent way to ensure similar mistakes are not made.

The same can be said for other safety issues in cars. There was a time when cars did not have seatbelts. The process to get seatbelts required in all cars started with a case study! The same can be said about airbags and collapsible steering columns. They all began with a case study that lead to larger research, and eventual change.

Exploratory

An exploratory case study is usually the precursor to a formal, large-scale research project. The case study's goal is to prove that further investigation is necessary.

For example, an exploratory case study could be done on veterans coming home from active combat. Researchers are aware that these vets have PTSD, and are aware that the actions of war are what cause PTSD. Beyond that, they do not know if certain wartime activities are more likely to contribute to PTSD than others.

For an exploratory case study, the researcher could develop a study that certain war events are more likely to cause PTSD. Once that is demonstrated, a large-scale research project could be done to determine which events are most likely to cause PTSD.

Exploratory case studies are very popular in psychology and the social sciences. Psychologists are always looking for better ways to treat their patients, and exploratory studies allow them to research new ideas or theories.

Multiple-Case Studies or Collective Studies

Multiple case or collective studies use information from different studies to formulate the case for a new study. The use of past studies allows additional information without needing to spend more time and money on additional studies.

Using the PTSD issue again is an excellent example of a collective study. When studying what contributes most to wartime PTSD, a researcher could use case studies from different war. For instance, studies about PTSD in WW2 vets, Persian Gulf War vets, and Vietnam vets could provide an excellent sampling of which wartime activities are most likely to cause PTSD.

If a multiple case study on vets was done with vets from the Vietnam War, the Persian Gulf War, and the Iraq War, and it was determined the vets from Vietnam had much less PTSD, what could be inferred?

Furthermore, this type of study could uncover differences as well. For example, a researcher might find that veterans who serve in the Middle East are more likely to suffer a certain type of ailment. Or perhaps, that veterans who served with large platoons were more likely to suffer from PTSD than veterans who served in smaller platoons.

An intrinsic case study is the study of a case wherein the subject itself is the primary interest. The "Genie" case is an example of this. The study wasn't so much about psychology, but about Genie herself, and how her experiences shaped who she was.

Genie is the topic. Genie is what the researchers are interested in, and what their readers will be most interested in. When the researchers started the study, they didn't know what they would find.

They asked the question…"If a child is never introduced to language during the crucial first years of life, can they acquire language skills when they are older?" When they met Genie, they didn't know the answer to that question.

Instrumental

An instrumental case study uses a case to gain insights into a phenomenon. For example, a researcher interested in child obesity rates might set up a study with middle school students and an exercise program. In this case, the children and the exercise program are not the focus. The focus is learning the relationship between children and exercise, and why certain children become obese.

What is an example of an instrumental case study?

Focus on the results, not the topic!

Types of Subjects of Case Studies

There are generally five different types of case studies, and the subjects that they address. Every case study, whether explanatory or exploratory, or intrinsic or instrumental, fits into one of these five groups. These are:

Person – This type of study focuses on one particular individual. This case study would use several types of research to determine an outcome.

The best example of a person case is the "Genie" case study. Again, "Genie" was a 13-year-old girl who was discovered by social services in Los Angeles in 1970. Her father believed her to be mentally retarded, and therefore locked her in a room without any kind of stimulation. She was never nourished or cared for in any way. If she made a noise, she was beaten.

When "Genie" was discovered, child development specialists wanted to learn as much as possible about how her experiences contributed to her physical, emotional and mental health. They also wanted to learn about her language skills. She had no form of language when she was found, she only grunted. The study would determine whether or not she could learn language skills at the age of 13.

Since Genie was placed in a children's hospital, many different clinicians could observe her. In addition, researchers were able to interview the few people who did have contact with Genie and would be able to gather whatever background information was available.

This case study is still one of the most valuable in all of child development. Since it would be impossible to conduct this type of research with a healthy child, the information garnered from Genie's case is invaluable.

Group – This type of study focuses on a group of people. This could be a family, a group or friends, or even coworkers.

An example of this type of case study would be the uncontacted tribes of Indians in the Peruvian and Brazilian rainforest. These tribes have never had any modern contact. Therefore, there is a great interest to study them.

Scientists would be interested in just about every facet of their lives. How do they cook, how do they make clothing, how do they make tools and weapons. Also, doing psychological and emotional research would be interesting. However, because so few of these tribes exist, no one is contacting them for research. For now, all research is done observationally.

If a researcher wanted to study uncontacted Indian tribes, and could only observe the subjects, what type of observations should be made?

Location – This type of study focuses on a place, and how and why people use the place.

For example, many case studies have been done about Siberia, and the people who live there. Siberia is a cold and barren place in northern Russia, and it is considered the most difficult place to live in the world. Studying the location, and it's weather and people can help other people learn how to live with extreme weather and isolation.

Location studies can also be done on locations that are facing some kind of change. For example, a case study could be done on Alaska, and whether the state is seeing the effects of climate change.

Another type of study that could be done in Alaska is how the environment changes as population increases. Geographers and those interested in population growth often do these case studies.

Organization/Company – This type of study focuses on a business or an organization. This could include the people who work for the company, or an event that occurred at the organization.

An excellent example of this type of case study is Enron. Enron was one of the largest energy company's in the United States, when it was discovered that executives at the company were fraudulently reporting the company's accounting numbers.

Once the fraud was uncovered, investigators discovered willful and systematic corruption that caused the collapse of Enron, as well as their financial auditors, Arthur Andersen. The fraud was so severe that the top executives of the company were sentenced to prison.

This type of case study is used by accountants, auditors, financiers, as well as business students, in order to learn how such a large company could get away with committing such a serious case of corporate fraud for as long as they did. It can also be looked at from a psychological standpoint, as it is interesting to learn why the executives took the large risks that they took.

Most company or organization case studies are done for business purposes. In fact, in many business schools, such as Harvard Business School, students learn by the case method, which is the study of case studies. They learn how to solve business problems by studying the cases of businesses that either survived the same problem, or one that didn't survive the problem.

Event – This type of study focuses on an event, whether cultural or societal, and how it affects those that are affected by it. An example would be the Tylenol cyanide scandal. This event affected Johnson & Johnson, the parent company, as well as the public at large.

The case study would detail the events of the scandal, and more specifically, what management at Johnson & Johnson did to correct the problem. To this day, when a company experiences a large public relations scandal, they look to the Tylenol case study to learn how they managed to survive the scandal.

A very popular topic for case studies was the events of September 11 th . There were studies in almost all of the different types of research studies.

Obviously the event itself was a very popular topic. It was important to learn what lead up to the event, and how best to proven it from happening in the future. These studies are not only important to the U.S. government, but to other governments hoping to prevent terrorism in their countries.

Planning A Case Study

You have decided that you want to research and write a case study. Now what? In this section you will learn how to plan and organize a research case study.

Selecting a Case

The first step is to choose the subject, topic or case. You will want to choose a topic that is interesting to you, and a topic that would be of interest to your potential audience. Ideally you have a passion for the topic, as then you will better understand the issues surrounding the topic, and which resources would be most successful in the study.

You also must choose a topic that would be of interest to a large number of people. You want your case study to reach as large an audience as possible, and a topic that is of interest to just a few people will not have a very large reach. One of the goals of a case study is to reach as many people as possible.

Who is your audience?

Are you trying to reach the layperson? Or are you trying to reach other professionals in your field? Your audience will help determine the topic you choose.

If you are writing a case study that is looking for ways to lower rates of child obesity, who is your audience?

If you are writing a psychology case study, you must consider whether your audience will have the intellectual skills to understand the information in the case. Does your audience know the vocabulary of psychology? Do they understand the processes and structure of the field?

You want your audience to have as much general knowledge as possible. When it comes time to write the case study, you may have to spend some time defining and explaining terms that might be unfamiliar to the audience.

Lastly, when selecting a topic you do not want to choose a topic that is very old. Current topics are always the most interesting, so if your topic is more than 5-10 years old, you might want to consider a newer topic. If you choose an older topic, you must ask yourself what new and valuable information do you bring to the older topic, and is it relevant and necessary.

Determine Research Goals

What type of case study do you plan to do?

An illustrative case study will examine an unfamiliar case in order to help others understand it. For example, a case study of a veteran with PTSD can be used to help new therapists better understand what veterans experience.

An exploratory case study is a preliminary project that will be the precursor to a larger study in the future. For example, a case study could be done challenging the efficacy of different therapy methods for vets with PTSD. Once the study is complete, a larger study could be done on whichever method was most effective.

A critical instance case focuses on a unique case that doesn't have a predetermined purpose. For example, a vet with an incredibly severe case of PTSD could be studied to find ways to treat his condition.

Ethics are a large part of the case study process, and most case studies require ethical approval. This approval usually comes from the institution or department the researcher works for. Many universities and research institutions have ethics oversight departments. They will require you to prove that you will not harm your study subjects or participants.

This should be done even if the case study is on an older subject. Sometimes publishing new studies can cause harm to the original participants. Regardless of your personal feelings, it is essential the project is brought to the ethics department to ensure your project can proceed safely.

Developing the Case Study

Once you have your topic, it is time to start planning and developing the study. This process will be different depending on what type of case study you are planning to do. For thissection, we will assume a psychological case study, as most case studies are based on the psychological model.

Once you have the topic, it is time to ask yourself some questions. What question do you want to answer with the study?

For example, a researcher is considering a case study about PTSD in veterans. The topic is PTSD in veterans. What questions could be asked?

Do veterans from Middle Eastern wars suffer greater instances of PTSD?

Do younger soldiers have higher instances of PTSD?

Does the length of the tour effect the severity of PTSD?

Each of these questions is a viable question, and finding the answers, or the possible answers, would be helpful for both psychologists and veterans who suffer from PTSD.

Research Notebook

1. What is the background of the case study? Who requested the study to be done and why? What industry is the study in, and where will the study take place?

2. What is the problem that needs a solution? What is the situation, and what are the risks?

3. What questions are required to analyze the problem? What questions might the reader of the study have? What questions might colleagues have?

4. What tools are required to analyze the problem? Is data analysis necessary?

5. What is your current knowledge about the problem or situation? How much background information do you need to procure? How will you obtain this background info?

6. What other information do you need to know to successfully complete the study?

7. How do you plan to present the report? Will it be a simple written report, or will you add PowerPoint presentations or images or videos? When is the report due? Are you giving yourself enough time to complete the project?

The research notebook is the heart of the study. Other organizational methods can be utilized, such as Microsoft Excel, but a physical notebook should always be kept as well.

Planning the Research

The most important parts of the case study are:

1. The case study's questions

2. The study's propositions

3. How information and data will be analyzed

4. The logic behind the propositions

5. How the findings will be interpreted

The study's questions should be either a "how" or "why" question, and their definition is the researchers first job. These questions will help determine the study's goals.

Not every case study has a proposition. If you are doing an exploratory study, you will not have propositions. Instead, you will have a stated purpose, which will determine whether your study is successful, or not.

How the information will be analyzed will depend on what the topic is. This would vary depending on whether it was a person, group, or organization.

When setting up your research, you will want to follow case study protocol. The protocol should have the following sections:

1. An overview of the case study, including the objectives, topic and issues.

2. Procedures for gathering information and conducting interviews.

3. Questions that will be asked during interviews and data collection.

4. A guide for the final case study report.

When deciding upon which research methods to use, these are the most important:

1. Documents and archival records

2. Interviews

3. Direct observations

4. Indirect observations, or observations of subjects

5. Physical artifacts and tools

Documents could include almost anything, including letters, memos, newspaper articles, Internet articles, other case studies, or any other document germane to the study.

Archival records can include military and service records, company or business records, survey data or census information.

Research Strategy

Before beginning the study you want a clear research strategy. Your best chance at success will be if you use an outline that describes how you will gather your data and how you will answer your research questions.

The researcher should create a list with four or five bullet points that need answers. Consider the approaches for these questions, and the different perspectives you could take.

The researcher should then choose at least two data sources (ideally more). These sources could include interviews, Internet research, and fieldwork or report collection. The more data sources used, the better the quality of the final data.

The researcher then must formulate interview questions that will result in detailed and in-depth answers that will help meet the research goals. A list of 15-20 questions is a good start, but these can and will change as the process flows.

Planning Interviews

The interview process is one of the most important parts of the case study process. But before this can begin, it is imperative the researcher gets informed consent from the subjects.

The process of informed consent means the subject understands their role in the study, and that their story will be used in the case study. You will want to have each subject complete a consent form.

The researcher must explain what the study is trying to achieve, and how their contribution will help the study. If necessary, assure the subject that their information will remain private if requested, and they do not need to use their real name if they are not comfortable with that. Pseudonyms are commonly used in case studies.

Informed Consent

The process by which permission is granted before beginning medical or psychological research

A fictitious name used to hide ones identity

It is important the researcher is clear regarding the expectations of the study participation. For example, are they comfortable on camera? Do they mind if their photo is used in the final written study.

Interviews are one of the most important sources of information for case studies. There are several types of interviews. They are:

Open-ended – This type of interview has the interviewer and subject talking to each other about the subject. The interviewer asks questions, and the subject answers them. But the subject can elaborate and add information whenever they see fit.

A researcher might meet with a subject multiple times, and use the open-ended method. This can be a great way to gain insight into events. However, the researcher mustn't rely solely on the information from the one subject, and be sure to have multiple sources.

Focused – This type of interview is used when the subject is interviewed for a short period of time, and answers a set of questions. This type of interview could be used to verify information learned in an open-ended interview with another subject. Focused interviews are normally done to confirm information, not to gain new information.

Structured – Structured interviews are similar to surveys. These are usually used when collecting data for large groups, like neighborhoods. The questions are decided before hand, and the expected answers are usually simple.

When conducting interviews, the answers are obviously important. But just as important are the observations that can be made. This is one of the reasons in-person interviews are preferable over phone interviews, or Internet or mail surveys.

Ideally, when conducing in-person interviews, more than one researcher should be present. This allows one researcher to focus on observing while the other is interviewing. This is particularly important when interviewing large groups of people.

The researcher must understand going into the case study that the information gained from the interviews might not be valuable. It is possible that once the interviews are completed, the information gained is not relevant.

- Course Catalog

- Group Discounts

- Gift Certificates

- For Libraries

- CEU Verification

- Medical Terminology

- Accounting Course

- Writing Basics

- QuickBooks Training

- Proofreading Class

- Sensitivity Training

- Excel Certificate

- Teach Online

- Terms of Service

- Privacy Policy

The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 1: The Basics

- Introduction and overview

- What is qualitative research?

- What is qualitative data?

- Examples of qualitative data

- Qualitative vs. quantitative research

- Mixed methods

- Qualitative research preparation

- Theoretical perspective

- Theoretical framework

- Literature reviews

Research question

- Conceptual framework

- Conceptual vs. theoretical framework

Data collection

- Qualitative research methods

- Focus groups

- Observational research

What is a case study?

Applications for case study research, what is a good case study, process of case study design, benefits and limitations of case studies.

- Ethnographical research

- Ethical considerations

- Confidentiality and privacy

- Power dynamics

- Reflexivity

Case studies

Case studies are essential to qualitative research , offering a lens through which researchers can investigate complex phenomena within their real-life contexts. This chapter explores the concept, purpose, applications, examples, and types of case studies and provides guidance on how to conduct case study research effectively.

Whereas quantitative methods look at phenomena at scale, case study research looks at a concept or phenomenon in considerable detail. While analyzing a single case can help understand one perspective regarding the object of research inquiry, analyzing multiple cases can help obtain a more holistic sense of the topic or issue. Let's provide a basic definition of a case study, then explore its characteristics and role in the qualitative research process.

Definition of a case study

A case study in qualitative research is a strategy of inquiry that involves an in-depth investigation of a phenomenon within its real-world context. It provides researchers with the opportunity to acquire an in-depth understanding of intricate details that might not be as apparent or accessible through other methods of research. The specific case or cases being studied can be a single person, group, or organization – demarcating what constitutes a relevant case worth studying depends on the researcher and their research question .

Among qualitative research methods , a case study relies on multiple sources of evidence, such as documents, artifacts, interviews , or observations , to present a complete and nuanced understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. The objective is to illuminate the readers' understanding of the phenomenon beyond its abstract statistical or theoretical explanations.

Characteristics of case studies

Case studies typically possess a number of distinct characteristics that set them apart from other research methods. These characteristics include a focus on holistic description and explanation, flexibility in the design and data collection methods, reliance on multiple sources of evidence, and emphasis on the context in which the phenomenon occurs.

Furthermore, case studies can often involve a longitudinal examination of the case, meaning they study the case over a period of time. These characteristics allow case studies to yield comprehensive, in-depth, and richly contextualized insights about the phenomenon of interest.

The role of case studies in research

Case studies hold a unique position in the broader landscape of research methods aimed at theory development. They are instrumental when the primary research interest is to gain an intensive, detailed understanding of a phenomenon in its real-life context.

In addition, case studies can serve different purposes within research - they can be used for exploratory, descriptive, or explanatory purposes, depending on the research question and objectives. This flexibility and depth make case studies a valuable tool in the toolkit of qualitative researchers.

Remember, a well-conducted case study can offer a rich, insightful contribution to both academic and practical knowledge through theory development or theory verification, thus enhancing our understanding of complex phenomena in their real-world contexts.

What is the purpose of a case study?

Case study research aims for a more comprehensive understanding of phenomena, requiring various research methods to gather information for qualitative analysis . Ultimately, a case study can allow the researcher to gain insight into a particular object of inquiry and develop a theoretical framework relevant to the research inquiry.

Why use case studies in qualitative research?

Using case studies as a research strategy depends mainly on the nature of the research question and the researcher's access to the data.

Conducting case study research provides a level of detail and contextual richness that other research methods might not offer. They are beneficial when there's a need to understand complex social phenomena within their natural contexts.

The explanatory, exploratory, and descriptive roles of case studies

Case studies can take on various roles depending on the research objectives. They can be exploratory when the research aims to discover new phenomena or define new research questions; they are descriptive when the objective is to depict a phenomenon within its context in a detailed manner; and they can be explanatory if the goal is to understand specific relationships within the studied context. Thus, the versatility of case studies allows researchers to approach their topic from different angles, offering multiple ways to uncover and interpret the data .

The impact of case studies on knowledge development

Case studies play a significant role in knowledge development across various disciplines. Analysis of cases provides an avenue for researchers to explore phenomena within their context based on the collected data.

This can result in the production of rich, practical insights that can be instrumental in both theory-building and practice. Case studies allow researchers to delve into the intricacies and complexities of real-life situations, uncovering insights that might otherwise remain hidden.

Types of case studies

In qualitative research , a case study is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Depending on the nature of the research question and the specific objectives of the study, researchers might choose to use different types of case studies. These types differ in their focus, methodology, and the level of detail they provide about the phenomenon under investigation.

Understanding these types is crucial for selecting the most appropriate approach for your research project and effectively achieving your research goals. Let's briefly look at the main types of case studies.

Exploratory case studies

Exploratory case studies are typically conducted to develop a theory or framework around an understudied phenomenon. They can also serve as a precursor to a larger-scale research project. Exploratory case studies are useful when a researcher wants to identify the key issues or questions which can spur more extensive study or be used to develop propositions for further research. These case studies are characterized by flexibility, allowing researchers to explore various aspects of a phenomenon as they emerge, which can also form the foundation for subsequent studies.

Descriptive case studies

Descriptive case studies aim to provide a complete and accurate representation of a phenomenon or event within its context. These case studies are often based on an established theoretical framework, which guides how data is collected and analyzed. The researcher is concerned with describing the phenomenon in detail, as it occurs naturally, without trying to influence or manipulate it.

Explanatory case studies

Explanatory case studies are focused on explanation - they seek to clarify how or why certain phenomena occur. Often used in complex, real-life situations, they can be particularly valuable in clarifying causal relationships among concepts and understanding the interplay between different factors within a specific context.

Intrinsic, instrumental, and collective case studies

These three categories of case studies focus on the nature and purpose of the study. An intrinsic case study is conducted when a researcher has an inherent interest in the case itself. Instrumental case studies are employed when the case is used to provide insight into a particular issue or phenomenon. A collective case study, on the other hand, involves studying multiple cases simultaneously to investigate some general phenomena.

Each type of case study serves a different purpose and has its own strengths and challenges. The selection of the type should be guided by the research question and objectives, as well as the context and constraints of the research.

The flexibility, depth, and contextual richness offered by case studies make this approach an excellent research method for various fields of study. They enable researchers to investigate real-world phenomena within their specific contexts, capturing nuances that other research methods might miss. Across numerous fields, case studies provide valuable insights into complex issues.

Critical information systems research

Case studies provide a detailed understanding of the role and impact of information systems in different contexts. They offer a platform to explore how information systems are designed, implemented, and used and how they interact with various social, economic, and political factors. Case studies in this field often focus on examining the intricate relationship between technology, organizational processes, and user behavior, helping to uncover insights that can inform better system design and implementation.

Health research

Health research is another field where case studies are highly valuable. They offer a way to explore patient experiences, healthcare delivery processes, and the impact of various interventions in a real-world context.

Case studies can provide a deep understanding of a patient's journey, giving insights into the intricacies of disease progression, treatment effects, and the psychosocial aspects of health and illness.

Asthma research studies

Specifically within medical research, studies on asthma often employ case studies to explore the individual and environmental factors that influence asthma development, management, and outcomes. A case study can provide rich, detailed data about individual patients' experiences, from the triggers and symptoms they experience to the effectiveness of various management strategies. This can be crucial for developing patient-centered asthma care approaches.

Other fields

Apart from the fields mentioned, case studies are also extensively used in business and management research, education research, and political sciences, among many others. They provide an opportunity to delve into the intricacies of real-world situations, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of various phenomena.

Case studies, with their depth and contextual focus, offer unique insights across these varied fields. They allow researchers to illuminate the complexities of real-life situations, contributing to both theory and practice.

Whatever field you're in, ATLAS.ti puts your data to work for you

Download a free trial of ATLAS.ti to turn your data into insights.

Understanding the key elements of case study design is crucial for conducting rigorous and impactful case study research. A well-structured design guides the researcher through the process, ensuring that the study is methodologically sound and its findings are reliable and valid. The main elements of case study design include the research question , propositions, units of analysis, and the logic linking the data to the propositions.

The research question is the foundation of any research study. A good research question guides the direction of the study and informs the selection of the case, the methods of collecting data, and the analysis techniques. A well-formulated research question in case study research is typically clear, focused, and complex enough to merit further detailed examination of the relevant case(s).

Propositions

Propositions, though not necessary in every case study, provide a direction by stating what we might expect to find in the data collected. They guide how data is collected and analyzed by helping researchers focus on specific aspects of the case. They are particularly important in explanatory case studies, which seek to understand the relationships among concepts within the studied phenomenon.

Units of analysis

The unit of analysis refers to the case, or the main entity or entities that are being analyzed in the study. In case study research, the unit of analysis can be an individual, a group, an organization, a decision, an event, or even a time period. It's crucial to clearly define the unit of analysis, as it shapes the qualitative data analysis process by allowing the researcher to analyze a particular case and synthesize analysis across multiple case studies to draw conclusions.

Argumentation

This refers to the inferential model that allows researchers to draw conclusions from the data. The researcher needs to ensure that there is a clear link between the data, the propositions (if any), and the conclusions drawn. This argumentation is what enables the researcher to make valid and credible inferences about the phenomenon under study.

Understanding and carefully considering these elements in the design phase of a case study can significantly enhance the quality of the research. It can help ensure that the study is methodologically sound and its findings contribute meaningful insights about the case.

Ready to jumpstart your research with ATLAS.ti?

Conceptualize your research project with our intuitive data analysis interface. Download a free trial today.

Conducting a case study involves several steps, from defining the research question and selecting the case to collecting and analyzing data . This section outlines these key stages, providing a practical guide on how to conduct case study research.

Defining the research question

The first step in case study research is defining a clear, focused research question. This question should guide the entire research process, from case selection to analysis. It's crucial to ensure that the research question is suitable for a case study approach. Typically, such questions are exploratory or descriptive in nature and focus on understanding a phenomenon within its real-life context.

Selecting and defining the case

The selection of the case should be based on the research question and the objectives of the study. It involves choosing a unique example or a set of examples that provide rich, in-depth data about the phenomenon under investigation. After selecting the case, it's crucial to define it clearly, setting the boundaries of the case, including the time period and the specific context.

Previous research can help guide the case study design. When considering a case study, an example of a case could be taken from previous case study research and used to define cases in a new research inquiry. Considering recently published examples can help understand how to select and define cases effectively.

Developing a detailed case study protocol

A case study protocol outlines the procedures and general rules to be followed during the case study. This includes the data collection methods to be used, the sources of data, and the procedures for analysis. Having a detailed case study protocol ensures consistency and reliability in the study.

The protocol should also consider how to work with the people involved in the research context to grant the research team access to collecting data. As mentioned in previous sections of this guide, establishing rapport is an essential component of qualitative research as it shapes the overall potential for collecting and analyzing data.

Collecting data

Gathering data in case study research often involves multiple sources of evidence, including documents, archival records, interviews, observations, and physical artifacts. This allows for a comprehensive understanding of the case. The process for gathering data should be systematic and carefully documented to ensure the reliability and validity of the study.

Analyzing and interpreting data

The next step is analyzing the data. This involves organizing the data , categorizing it into themes or patterns , and interpreting these patterns to answer the research question. The analysis might also involve comparing the findings with prior research or theoretical propositions.

Writing the case study report

The final step is writing the case study report . This should provide a detailed description of the case, the data, the analysis process, and the findings. The report should be clear, organized, and carefully written to ensure that the reader can understand the case and the conclusions drawn from it.

Each of these steps is crucial in ensuring that the case study research is rigorous, reliable, and provides valuable insights about the case.

The type, depth, and quality of data in your study can significantly influence the validity and utility of the study. In case study research, data is usually collected from multiple sources to provide a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case. This section will outline the various methods of collecting data used in case study research and discuss considerations for ensuring the quality of the data.

Interviews are a common method of gathering data in case study research. They can provide rich, in-depth data about the perspectives, experiences, and interpretations of the individuals involved in the case. Interviews can be structured , semi-structured , or unstructured , depending on the research question and the degree of flexibility needed.

Observations

Observations involve the researcher observing the case in its natural setting, providing first-hand information about the case and its context. Observations can provide data that might not be revealed in interviews or documents, such as non-verbal cues or contextual information.

Documents and artifacts

Documents and archival records provide a valuable source of data in case study research. They can include reports, letters, memos, meeting minutes, email correspondence, and various public and private documents related to the case.

These records can provide historical context, corroborate evidence from other sources, and offer insights into the case that might not be apparent from interviews or observations.

Physical artifacts refer to any physical evidence related to the case, such as tools, products, or physical environments. These artifacts can provide tangible insights into the case, complementing the data gathered from other sources.

Ensuring the quality of data collection

Determining the quality of data in case study research requires careful planning and execution. It's crucial to ensure that the data is reliable, accurate, and relevant to the research question. This involves selecting appropriate methods of collecting data, properly training interviewers or observers, and systematically recording and storing the data. It also includes considering ethical issues related to collecting and handling data, such as obtaining informed consent and ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of the participants.

Data analysis

Analyzing case study research involves making sense of the rich, detailed data to answer the research question. This process can be challenging due to the volume and complexity of case study data. However, a systematic and rigorous approach to analysis can ensure that the findings are credible and meaningful. This section outlines the main steps and considerations in analyzing data in case study research.

Organizing the data

The first step in the analysis is organizing the data. This involves sorting the data into manageable sections, often according to the data source or the theme. This step can also involve transcribing interviews, digitizing physical artifacts, or organizing observational data.

Categorizing and coding the data

Once the data is organized, the next step is to categorize or code the data. This involves identifying common themes, patterns, or concepts in the data and assigning codes to relevant data segments. Coding can be done manually or with the help of software tools, and in either case, qualitative analysis software can greatly facilitate the entire coding process. Coding helps to reduce the data to a set of themes or categories that can be more easily analyzed.

Identifying patterns and themes

After coding the data, the researcher looks for patterns or themes in the coded data. This involves comparing and contrasting the codes and looking for relationships or patterns among them. The identified patterns and themes should help answer the research question.

Interpreting the data

Once patterns and themes have been identified, the next step is to interpret these findings. This involves explaining what the patterns or themes mean in the context of the research question and the case. This interpretation should be grounded in the data, but it can also involve drawing on theoretical concepts or prior research.

Verification of the data

The last step in the analysis is verification. This involves checking the accuracy and consistency of the analysis process and confirming that the findings are supported by the data. This can involve re-checking the original data, checking the consistency of codes, or seeking feedback from research participants or peers.

Like any research method , case study research has its strengths and limitations. Researchers must be aware of these, as they can influence the design, conduct, and interpretation of the study.

Understanding the strengths and limitations of case study research can also guide researchers in deciding whether this approach is suitable for their research question . This section outlines some of the key strengths and limitations of case study research.

Benefits include the following:

- Rich, detailed data: One of the main strengths of case study research is that it can generate rich, detailed data about the case. This can provide a deep understanding of the case and its context, which can be valuable in exploring complex phenomena.

- Flexibility: Case study research is flexible in terms of design , data collection , and analysis . A sufficient degree of flexibility allows the researcher to adapt the study according to the case and the emerging findings.

- Real-world context: Case study research involves studying the case in its real-world context, which can provide valuable insights into the interplay between the case and its context.

- Multiple sources of evidence: Case study research often involves collecting data from multiple sources , which can enhance the robustness and validity of the findings.

On the other hand, researchers should consider the following limitations:

- Generalizability: A common criticism of case study research is that its findings might not be generalizable to other cases due to the specificity and uniqueness of each case.

- Time and resource intensive: Case study research can be time and resource intensive due to the depth of the investigation and the amount of collected data.

- Complexity of analysis: The rich, detailed data generated in case study research can make analyzing the data challenging.

- Subjectivity: Given the nature of case study research, there may be a higher degree of subjectivity in interpreting the data , so researchers need to reflect on this and transparently convey to audiences how the research was conducted.

Being aware of these strengths and limitations can help researchers design and conduct case study research effectively and interpret and report the findings appropriately.

Ready to analyze your data with ATLAS.ti?

See how our intuitive software can draw key insights from your data with a free trial today.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Explanatory Research: Definition, Types & Guide

There are many types of research, but today, we want to talk to you about one, in particular, that will give you a new perspective on your objects of study; for that, we have created this guide with everything you need to know about explanatory research . After all, w hat is the purpose of explanatory research?

What is Explanatory Research?

Explanatory research is a method developed to investigate a phenomenon that has not been studied or explained properly. Its main intention is to provide details about where to find a small amount of information.

With this method, the researcher gets a general idea and uses research as a tool to guide them quicker to the issues that we might address in the future. Its goal is to find the why and what of an object of study.

Explanatory research is responsible for finding the why of the events by establishing cause-effect relationships. Its results and conclusions constitute the deepest level of knowledge, according to author Fidias G. Arias. In this sense, explanatory studies can deal with the determination of causes (post-facto research) and effects ( experimental research ) through hypothesis testing.

Characteristics of Explanatory Research

Among the most critical characteristics of explanatory research are:

- It allows for an increased understanding of a specific topic. Although it does not offer conclusive results, the researcher can find out why a phenomenon occurs.

- It uses secondary research as a source of information, such as literature or published articles, that are carefully chosen to have a broad and balanced understanding of the topic.

- It allows the researcher to have a broad understanding of the topic and refine subsequent research questions to augment the study’s conclusions.

- Researchers can distinguish the causes why phenomena arising during the research design process and anticipate changes.

- Explanatory research allows them to replicate studies to give them greater depth and gain new insights into the phenomenon.

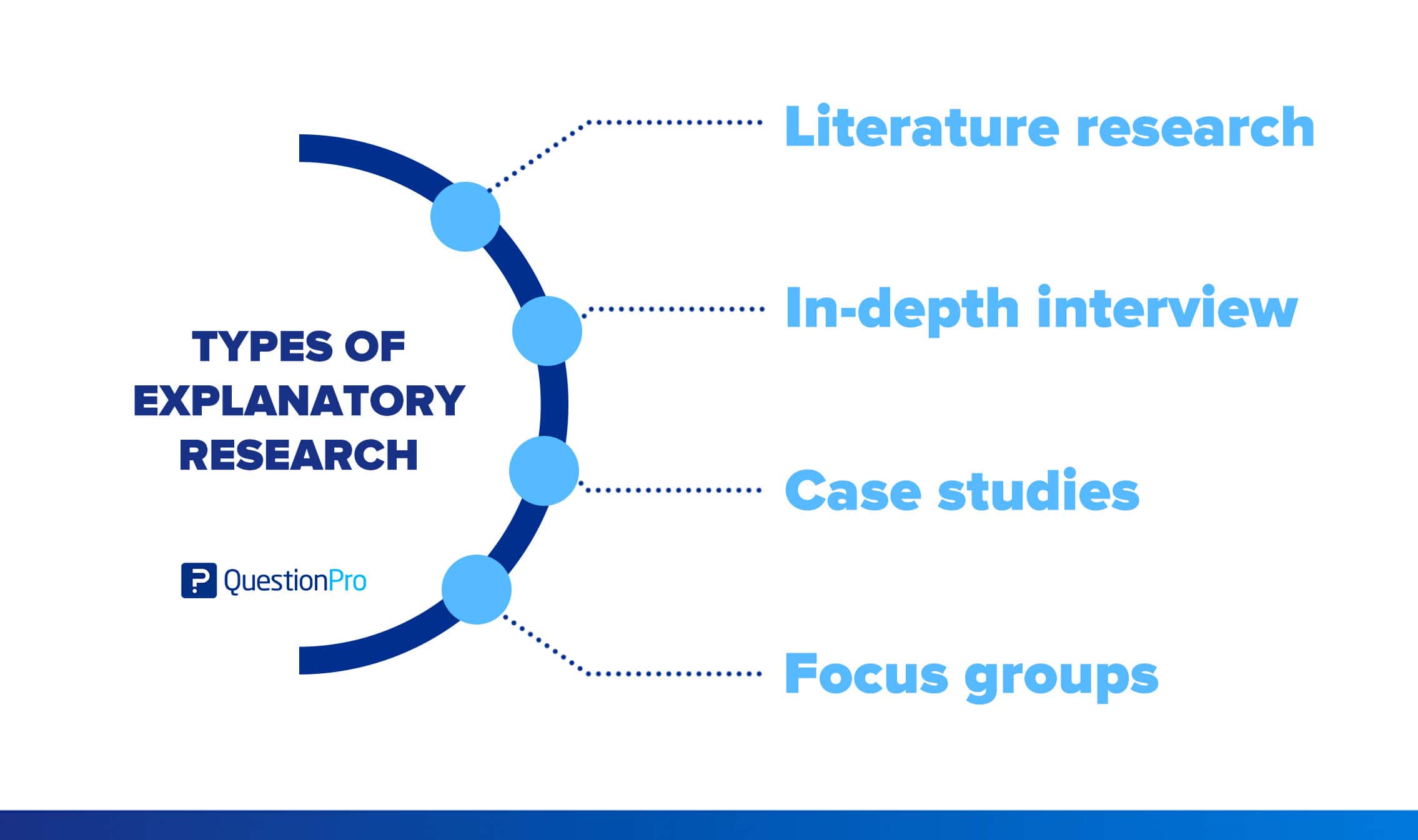

Types of Explanatory Research

The most popular methods of explanatory research:

- Literature research: It is one of the fastest and least expensive means of determining the hypothesis of the phenomenon and collecting information. It involves searching for literature on the internet and in libraries. It can, of course, be in magazines, newspapers, commercial and academic articles.

- In-depth interview: The process involves talking to a knowledgeable person about the topic under investigation. The in-depth interview is used to take advantage of the information offered by people and their experience, whether they are professionals within or outside the organization.

- Focus groups: Focus groups consist of bringing together 8 to 12 people who have information about the phenomenon under study and organizing sessions to obtain from these people various data that will help the research.

- Case studies: This method allows researchers to deal with carefully selected cases. Case analysis allows the organization to observe companies that have faced the same issue and deal with it more efficiently.

Check out our library of QuestionPro Case Studies to learn more about how we help organizations conduct market research.

Importance of explanatory research

Explanatory research is conducted to help researchers study the research problem in greater depth and understand the phenomenon efficiently.

The primary use for explanatory research is problem-solving by finding the overlooked data that we had never investigated before. At the same time, it might not bring out conclusive data; it will allow us to understand the issue more efficiently.

In carrying out the research process, it is necessary to adapt to new findings and knowledge about the subject. Although it is impossible to conclude, it is possible to explore the variables with a high level of depth.

Explanatory research allows the researcher to become familiar with the topic to be examined and design theories to test them.

Explanatory Reseach Quick Guide

Explanatory research is a great method to use if you’re looking to understand why something is happening. Here’s a quick guide on how to conduct explanatory research:

- Clearly define your research question and objectives. This will help guide your research and ensure that you collect the right data.

- Choose your research methods. Explanatory research can be done using both qualitative and quantitative methods. Some popular methods include surveys, interviews, experiments, and observational studies.

- Collect and analyze your data. Once you’ve chosen your methods, it’s time to collect your data. Make sure to keep accurate records and organize your data so it’s easy to analyze.

- Draw conclusions and make recommendations. After analyzing your data, it’s time to draw conclusions and make recommendations based on your findings. Be sure to present your conclusions clearly and concisely and ensure your data supports them.

- Communicate your findings. Share your research findings with others, including your colleagues, stakeholders, or clients. Also, make sure to communicate your findings in a way that is easy for others to understand and act upon.

Remember that explanatory research is about understanding the relationship between variables, so be sure to keep that in mind when designing your research, collecting and analyzing your data, and communicating your findings.

Advantages and Conclusions

This method is precious for social research . It a llows researchers to find a phenomenon we did not study in depth. Although it does not conclude such a study, it helps to understand the problem efficiently. It’s essential to convey new data about a point of view on the study.

People who conduct explanatory research do so to study the interaction of the phenomenon in detail. Therefore, it is vital to have enough information to carry it out.

Finally, we invite you to refer to our market research guide . You can do incredible research and collect data free with our survey software . Get started now!

FREE TRIAL LEARN MORE

MORE LIKE THIS

Data Information vs Insight: Essential differences

May 14, 2024

Pricing Analytics Software: Optimize Your Pricing Strategy

May 13, 2024

Relationship Marketing: What It Is, Examples & Top 7 Benefits

May 8, 2024

The Best Email Survey Tool to Boost Your Feedback Game

May 7, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

- Explanatory Research: Types, Examples, Pros & Cons

Explanatory research is designed to do exactly what it sounds like: explain, and explore. You ask questions, learn about your target market, and develop hypotheses for testing in your study. This article will take you through some of the types of explanatory research and what they are used for.

What is Explanatory Research?

Explanatory research is defined as a strategy used for collecting data for the purpose of explaining a phenomenon. Because the phenomenon being studied began with a single piece of data, it is up to the researcher to collect more pieces of data.

In other words, explanatory research is a method used to investigate a phenomenon (a situation worth studying) that had not been studied before or had not been well explained previously in a proper way. It is a process in which the purpose is to find out what would be a potential answer to the problem.

This method of research enables you to find out what does not work as well as what does and once you have found this information, you can take measures for developing better alternatives that would improve the process being studied. The goal of explanatory research is to answer the question “How,” and it is most often conducted by people who want to understand why something works the way it does, or why something happens as it does.

Read: How to Write a Problem Statement for your Research

By using this method, researchers are able to explain why something is happening and how it happens. In other words, explanatory research can be used to “explain” something, by providing the right context. This is usually done through the use of surveys and interviews.

Importance of Explanatory Research

Explanatory research helps researchers to better understand a subject, but it does not help them to predict what might happen in the future. Explanatory research is also known by other names, such as ex post facto (Latin for “after the fact”) and causal research.

The most important goal of explanatory research is to help understand a given phenomenon. This can be done through basic or applied research .

Basic explanatory research, also known as pure or fundamental research, is conducted without any specific real-world application in mind. Applied explanatory research attempts to develop new knowledge that can be used to improve humans’ everyday lives.

Read: How to Write a Thesis Statement for Your Research: Tips + Examples

For example, you might want to know why people buy certain products, why companies change their business processes, or what motivates people in the workplace. Explanatory research starts with a theory or hypothesis and then gathers evidence to prove or disprove the theory.

Most explanatory research uses surveys to gather information from a pool of respondents . The results will then provide information about the target population as a whole.

Purpose of Explanatory Research

The purpose of explanatory research is to explore a topic and develop a deeper understanding of it so that it can be described or explained more fully. The researcher sets out with a specific question or hypothesis in mind, which will guide the data collection and analysis process.

Explanatory research can take any number of forms, from experimental studies in which researchers test a hypothesis by manipulating variables, to interviews and surveys that are used to gather insights from participants about their experiences. Explanatory research seeks neither to generate new knowledge nor solve a specific problem; rather it seeks to understand why something happens.

For example, imagine that you would like to know whether one’s age affects his or her ability to use a particular type of computer software. You develop the hypothesis that older people will have more difficulty using the software than younger people.

In order to test your hypothesis and learn more about the relationship between age and software usage, you design and conduct an explanatory study.

Read: How to Write An Abstract For Research Papers: Tips & Examples

Characteristics of Explanatory Research

Explanatory research is used to explain something that has already happened but it doesn’t try to control anything, nor does it seek to predict what will happen. Instead, its aim is to understand what has happened when it comes to a certain phenomenon.

Here are some of the characteristics of explanatory research, they include:

- It is used when the researcher wants to explain the relationship between two variables that the researcher cannot manipulate. This means that the researcher must rely on secondary data instead to understand the variables.

- In explanatory research, the data is collected before the study begins and is usually collected by a different individual/organization than that of the researcher.

- Explanatory research does not involve random sampling or random allocation (the process of assigning subjects and participants to different study groups).

Types of Explanatory Research

Explanatory research generally focuses on the “why” questions. For example, a business might ask why customers aren’t buying their product or how they can improve their sales process. Types of explanatory research include:

1. Case studies: Case studies allow researchers to examine companies that experienced the same situation as them. This helps them understand what worked and what didn’t work for the other company.

Explore: Formplus Customer Success Stories and Case Studies

2. Literature research: Literature research involves examining and reviewing existing academic literature on a topic related to your projects, such as a particular strategy or method. Literature research allows researchers to see how other people have discussed a similar problem and how they arrived at their conclusions.

3. Observations: Observations involve gathering information by observing events without interfering with them. They’re useful for gathering information about social interactions, such as who talks to whom on a subway platform or how people react to certain ads in public spaces, like billboards and bus shelters.

4. Pilot studies: Pilot studies are small versions of larger studies that help researchers prepare for larger studies by testing out methods, procedures, or instruments before using them in the final study design.

Read: Research Report: Definition, Types + [Writing Guide]

5. Focus groups: Focus groups involves gathering a group of people so participants can share opinions, instead of answering questions

Difference between Explanatory and Exploratory Research