Staff and Board

Funders and Supporters

Job Opportunities

News Releases

Media Coverage

Education and Training

Capacity Building Assistance

Research and Evaluation

Alive Maryland

- ASO/CBO National Directory

ASO/CBO Leadership Training

Black Women’s Health Collaborative Learning Series

Board Leadership Training

Effi Barry Training Institute

E-Learning Center

Fiscal Health Training

Harm Reduction Learning Institute

HealthLGBTQ

HIV Prevention Certified Provider™ Certification Program

Partnering and Communicating Together (PACT)

Pozitively Aging

REINFORCE Center for Retention in HIV Care

Remaining Relevant in the New Reality

"State of" National Surveys

SYNChronicity

TeleHealthHIV

HIV Treatment Innovation Certificate Program

HIV PrEP Navigation Certification Program

LGBTQ Health Training and Certificate Program™

Newsletter Sign-Up

Request ASO/CBO CBA

Request Fiscal Health Professional Services

Join the National Coalition for LGBTQ Health

- HealthHIV Resources

- External Resources

- HIV Prevention Certified Provider Program

- Mpox Resource Center

- HIV Testing and Care Services Locator

How I Knew I Had HIV: Stories by Real People Living with HIV

Everyone’s experience is different, and that’s important because NO ONE symptom just shows up to indicate that you might have HIV. In fact, most people feel no symptoms at all prior to finding out. That is why getting tested is so important. In the beginning, it can be frightening, but these individuals overcame their fears and have triumphed.

- February 1, 2022

Subject Matter

Related programs, related resources.

Aging and PrEP: Considerations for PrEP in People 50 Years of Age and Older

Integrating Frailty and Functional Outcomes into Clinical Trials

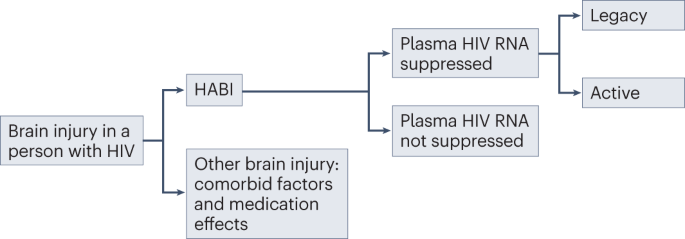

HIV Clinical, Comorbid, and Social Determinants of Health are Linked with Brain Aging

The Science of Aging: Lessons for HIV at the Interface of Commonality and Heterogeneity

HIV and Aging: Double Stigma

National HIV Curriculum: HIV in Older Adults

- 1630 Connecticut Ave, NW, Suite 500, Washington D.C. 20009

- 202.232.6749

- 202.232.6750

- [email protected]

© Copyright 2024 HealthHIV. All rights reserved.

- Open access

- Published: 07 December 2021

The lived experience of HIV-infected patients in the face of a positive diagnosis of the disease: a phenomenological study

- Behzad Imani ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1544-8196 1 ,

- Shirdel Zandi 2 ,

- Salman khazaei 3 &

- Mohamad Mirzaei 4

AIDS Research and Therapy volume 18 , Article number: 95 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

7543 Accesses

3 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

AIDS as a human crisis may lead to devastating psychological trauma and stress for patients. Therefore, it is necessary to study different aspects of their lives for better support and care. Accordingly, this study aimed to explain the lived experience of HIV-infected patients in the face of a positive diagnosis of the disease.

This qualitative study is a descriptive phenomenological study. Sampling was done purposefully and participants were selected based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Data collection was conducted, using semi-structured interviews. Data analysis was performed using Colaizzi’s method.

12 AIDS patients participated in this study. As a result of data analysis, 5 main themes and 12 sub-themes were identified, which include : emotional shock (loathing, motivation of social isolation), the fear of the consequences (fear of the death, fear of loneliness, fear of disgrace), the feeling of the guilt (feeling of regret, feeling guilty, feeling of conscience-stricken), the discouragement (suicidal ideation, disappointment), and the escape from reality (denial, trying to hide).

The results of this study showed that patients will experience unpleasant phenomenon in the face of the positive diagnosis of the disease and will be subjected to severe psychological pressures that require attention and support of medical and laboratory centers.

Patients will experience severe psychological stress in the face of a positive diagnosis of HIV.

Patients who are diagnosed with HIV are prone to make a blunder and dreadful decisions.

AIDS patients need emotional and informational support when they receive a positive diagnosis.

As a piece of bad news, presenting the positive diagnosis of HIV required the psychic preparation of the patient

Introduction

HIV/AIDS pandemic is one of the most important economic, social, and human health problems in many countries of the world, whose, extent and dimensions are unfortunately ever-increasing [ 1 ]. In such circumstances, this phenomenon should be considered as a crisis, which seriously affects all aspects of the existence and life of patients and even the health of society [ 2 ]. Diagnosing and contracting HIV/AIDS puts a person in a vague and difficult situation. Patients suffer not only from the physical effects of the disease, but also from the disgraceful consequences of the disease. HIV/AIDS is usually associated with avoidable behaviors that are not socially acceptable, such as unhealthy sexual, relations and drug abuse: So the patients are usually held guilty for their illness [ 3 ]. On the other hand, the issue of disease stigma in the community is the cause of rejection and isolation of these patients, and in health care centers is a major obstacle to providing services to these patients [ 4 ]. Studies show that HIV/AIDS stigma has a completely negative effect on the quality of life of these patients [ 5 ]. Criminal attitudes towards these patients and disappointing behavior by family, community, and medical staff cause blame and discrimination in patients [ 6 ]. HIV/AIDS stigma is prevalent among diseases, making concealment a major problem in this behavioral disease. The stigma comes in two forms: a negative inner feeling and a negative feeling that other people in the community have towards the patient [ 7 ]. The findings of a study that conducted in Iran indicated that increasing HIV/AIDS-related stigma decreases quality of life of people living with HIV/AIDS [ 8 ]. Robert Beckman has defined bad news as “any news that seriously and unpleasantly affects persons’ attitudes toward their future”. He considers the impact of counseling on moderating a person’s feeling of being important [ 9 ]. Therefore, being infected by HIV / AIDS due to the stigma can be bad news, which will lead to unpleasant emotional reactions [ 10 ]. Studies that have examined the lives of these patients have shown that these patients will experience mental and living problems throughout their lives. These studies highlight the need for age-specific programming to increase HIV knowledge and coping, increase screening, and improve long-term planning [ 11 , 12 ].

A prerequisite for any successful planning and intervention for people living with HIV/AIDS is approaching them and conducting in-depth interviews in order to discover their feelings, attitudes; their views on themselves, their illness, and others; and finally, their motivation to follow up and the participation in interventions [ 13 ]. Accordingly, the present study aimed to explain the lived experience of HIV-infected patients in the face of a positive diagnosis of the disease, since the better understanding of the phenomena leads to the smoother ways to help and care for these patients.

Study setting

In this study, a qualitative method of descriptive phenomenology was used to discover and interpret the lived experience of HIV-positive patients, when they face a positive diagnosis of the disease. The philosophical strengths underlying descriptive phenomenology afford a deeper understanding of the phenomenon being studied [ 14 ]. Husserl’s four steps of descriptive phenomenology were employed: bracketing, intuiting, analyzing and interpreting [ 15 ].

Participants and sampling

Sampling was done purposefully and participants were selected based on inclusion criteria. In this purposeful sampling, participants were selected among those patients who had sufficient knowledge about this phenomenon. The sample size was not determined at the beginning of the study, instead, it continued until no new idea emerged and data-saturated. Participants were selected from patients who were admitted to the Shohala Behavioral Diseases Counseling Center in Hamadan-Iran. The center has been set up to conduct tests, consultations, medical and dental services, and to distribute medicines among the patients. Additional inclusion criteria for selecting a participant are: having a positive diagnosis experience at the center, Ability to recall events and mental thoughts in the face of the first positive diagnosis of the disease, having psychological and mental stability, having a favorable clinical condition, willingness to work with the research team, and the possibility of re-access for the second interview if needed. Exclusion criteria were unwillingness to participate in the study and inability of verbal communication in Persian language.

Data collection

The interviews began with a non-structured question (tell us about your experience with a positive diagnosis) and continued with semi-structured questions. Each interview lasted 35–70 min and was conducted in two sessions if necessary. All interviews were conducted by the main investigator (ShZ) that who has experience in qualitative research and interviewing. The interview was recorded and then written down with permission of the participant.

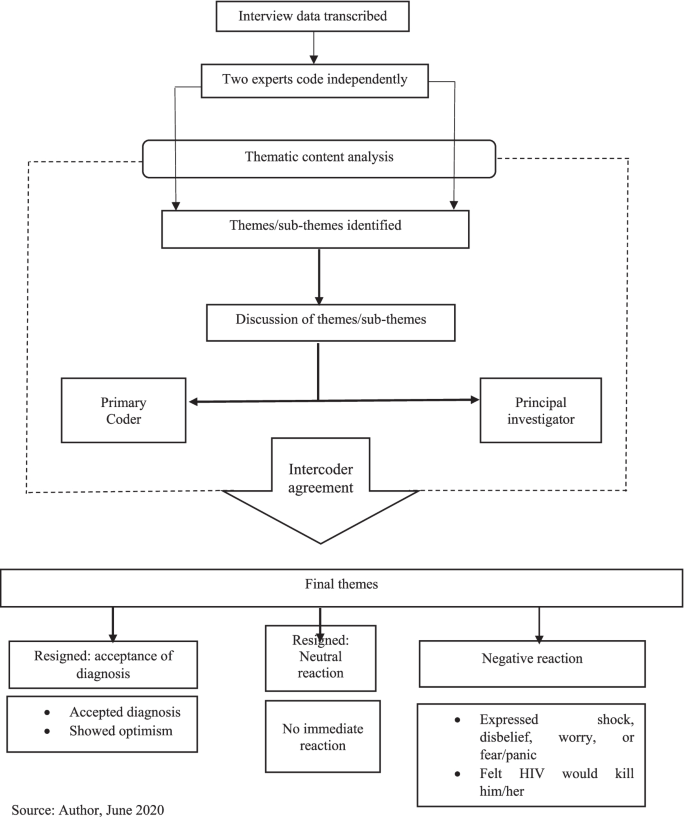

Data analysis

The descriptive Colaizzi method was used to analyses the collected data [ 16 ]. This method consists of seven steps: (1) collecting the participants’ descriptions, (2) understanding the meanings in depth, (3) extracting important sentences, (4) conceptualizing important themes, (5) categorizing the concepts and topics, (6) constructing comprehensive descriptions of the issues examined, and (7) validating the data following the four criteria set out by Lincoln and Guba.

Trustworthiness criteria were used to validate the research, due to the fact that importance of data and findings validity in qualitative research [ 17 ]. This study was based on four criteria of Lincoln and Guba: credibility, transferability, dependability, and conformability [ 18 ]. For data credibility, prolong engagement and follow-up observations, as well as samplings with maximum variability were used. For dependability of the data, the researchers were divided into two groups and the research was conducted as two separate studies. At the same time, another researcher with the most familiarity and ability in conducting qualitative research, supervised the study as an external observer. Concerning the conformability, the researchers tried not to influence their own opinions in the coding process. Moreover, the codes were readout by the participants as well as two researcher colleagues with the help of an independent researcher and expert familiar with qualitative research. Transferability of data was confirmed by offering a comprehensive description of the subject, participants, data collection, and data analysis.

Ethical considerations (ethical approval)

The present study was registered with the ethics code IR.UMSHA.REC.1398.1000 in Hamadan University of Medical Sciences. The purpose of the study was explained and all participants’ consents were obtained at first step. All participants were assured that the information obtained would remain confidential and no personal information would be disclosed. Participants were also told that there was no need to provide any personal information to the interviewer, including name, surname, phone number and address. To gain more trust, interviews were conducted by a person who was not resident of Hamadan and was not a native of the region, this case was also reported to the participants.

Twelve HIV-infected participated in this study. The mean age of the participants was 36.41 ± 4.12 years. 58.33% of the participants were male and 41.66% were married. Of these, 2 were illiterate, 2 had elementary diploma, 6 had high school diploma and 2 had academic education. Six of them were unemployed, 5 were self-employed and 1 was an official employee. These people had been infected by this disease for 6.08 ± 2.71 years, in average (Table 1 ).

Analysis of the HIV-infected patients’ experiences of facing the positive diagnosis of the disease by descriptive phenomenology revealed five main themes: emotional shock, the fear of the consequences, the feeling of the guilt, the discouragement, and the escape from reality (Table 2 ).

Emotional shock

Emotional shock is one of the unpleasant events that these patients have experienced after facing a positive diagnosis of the disease. This experience has manifested in loathing and motivation of social isolation.

These patients stated that after facing a positive diagnosis of the disease, they developed a strong inner feeling of hatred towards the source of infection. The patients feel hatred, since they hold the carrier as responsible for their infection. “…After realizing I was affected, I felt very upset with my husband, I did not want to see him again, because it made me miserable, I even decided to divorce ….”(P3).

Motivation of social isolation

The experiences of these patients showed that after facing the incident, they have suffered an internal failure that has caused them to try to distance from other people. These patients have become isolated, withdrawing from the community and sometimes even from their families. “…After this incident, I decided to live alone forever and stay away from all my family members. I made a good excuse and broke up our engagement…” (P7).

Fear of the consequences

Fear of the consequences is one of the unpleasant experiences that these patients will face, as soon as they receive a positive diagnosis of the disease. Based on experiences, these patients feel fear of loneliness, death, and disgrace as soon as they hear the positive diagnosis.

Fear of the death

The patients said that as soon as they got the positive test results, they thought that the disease was incurable and would end their lives soon. “…When I found I had AIDS, I was very upset and moved like a dead man because I was really afraid that at any moment this disease might kill me and I would die …” (P1).

Fear of loneliness

The participants stated that one of the feelings that they experienced as soon as they received a positive diagnosis of the disease was the fear of being alone. They stated that at that moment, the thought of being excluded from society and losing their intimacy with them was very disturbing. “…The thought that I could no longer have a family and had to stay single forever bothered me a lot, it was terrifying to me when I thought that society could no longer accept me as a normal person …” (P10).

Fear of disgrace

One of the feelings that these patients experienced when faced the positive diagnosis of the disease was the fear of disgrace. They suffer from the perception that the spread of news of the illness hurts the attitudes of those around them and causes them to be discredited. “…It was very annoying for me when I thought I would no longer be seen as a member of my family, I felt I would no longer have a reputation and everyone would think badly of me …” (P2).

Feeling of the guilt

From other experiences of these patients in facing the positive diagnosis of the disease is feeling guilty. This feeling appears in patients as feeling of regret, guilty and remorse.

Feeling of regret

These patients stated that they felt remorse for their lifestyle and actions as soon as they heard the positive diagnosis of the disease, because they thought that if they had lived healthier, they would not have been infected. “…After realizing this disease, I was very sorry for my past, because I really did not have a healthy life. I made a series of mistakes that caused me to get caught. At that moment, I just regretted why I had this disaster …” (P11).

Feeling guilty

The experience of these patients has shown that after receiving a positive diagnosis of the disease, they consider themselves guilty and complain about themselves. These patients condemn their lifestyle and sometimes even consider themselves deserving of the disease and think that it is a ransom that they have paid back. “…after getting the disease, I realized that I was paying the ransom because I was hundred percent guilty, I was the one who caused this situation with a series of bad deeds, and now I have to be punished …” (P5).

Feeling of conscience-stricken

One of the experiences that these patients reported is the pangs of conscience. These patients stated that after receiving a positive diagnosis of the disease, the thought that as a carrier they might have contaminated those around them was very unpleasant and greatly affected their psyche. “…after getting the disease. It was shocked and I was just crazy about the fact that if my wife and children had taken this disease from me, what would I do, I made them hapless … and this as very annoying for me …” (P8).

Discouragement

Discouragement is an unpleasant experience that patients experienced after receiving a positive HIV test results. Discouragement in these patients appears in the suicidal ideation and disappointment.

Suicidal ideation

The patients stated that they were so upset with the positive diagnosis of the illness and they immediately thought they could not live with the fact and the best thing to do was to end their own lives. “…The news was so bad for me that I immediately thought that if the test result was correct and I had AIDS, I would have to kill myself and end this wretch life, oh, I had a lot of problem and the thought of having to wait for a gradual death was horrible to me …” (P12).

Disappointment

The experience of these patients shows that a positive diagnosis of the disease for these patients leads to a destructive feeling of disappointment. So that they are completely discouraged from their lives. These patients think that their dreams and goals are vanished and that they have reached the end and everything is over. “…It was a horrible experience, so at that moment I felt my life was over, I had to prepare myself for a gradual death, I was at marriage ages when I thought I could no longer get married, I saw life as meaningless …” (P7).

Escape from reality

The lived experience of these patients shows that after receiving a positive diagnosis of the disease, they found that this fact was difficult to accept and somehow tried to escape from the reality. This experience has been in the form of denial and trying to hide from others.

One of the experiences of these patients in dealing with the positive test result of this disease has been to deny it. In this way, patients believed that the test result was wrong or that the result belonged to someone else. For this reason, the patients referred to other laboratories after receiving the first positive diagnosis of the disease. “…After the lab told me this and found out what the disease really was, I was really shocked and said it was impossible, it was definitely wrong and it is not true … I could not believe it at all, because I was a professional athlete and this could not happen to me. So I immediately went to a bigger city and there I went to a few laboratories for further tests …” (P6).

Trying to hide

These patients stated that after receiving the first positive diagnosis of the disease, they thought that no one should notice their disease and should remain anonymous as much as possible. “…I immediately decided that no one in my city should know that I got this disease and the news should not be spread anywhere, so I discard my phone number through which our city laboratory communicated with me and I came here to do a re-examination and go to the doctor, and after all these years, I always come here again for an examination …” (P4).

In this qualitative study, we attempted to discover lived experience of HIV-infected patients in the face of a positive diagnosis of the disease. Therefore, a descriptive phenomenological method was applied. As a result of this study, based on the experiences of the HIV-infected patients, the five main themes of emotional shock, fear of the consequences, feelings of guilt, discouragement and, escape from reality were obtained.

In this study, it was shown that the confrontation of these patients with the positive diagnosis of the disease causes them to experience a severe emotional shock. In this regard, Yangyang Qiu et al. [ 19 ] argued that anxiety and depression are very common among HIV-infected patients who have recently been diagnosed with the disease. The experience of the participants has shown that this emotional shock appears in the form of loathing and the motivation of social isolation. In fact, in these patients, the feeling of the loathing is an emotional response to the primary carrier that has infected them. The study of Imani et al. [ 20 ] have shown that decrease emotional intelligence in an environment where there is an HIV carrier, other people hate him/her, because they see him/her as a risk factor for their infection. The experience of the participants has also shown that receiving a positive diagnosis will motivate social isolation in these patients. Various studies have revealed that one of the consequences of AIDS/HIV that patients will suffer from, is social isolation [ 21 , 22 ].

Another experience of the participants, according to this study is fear of the consequences. This phenomenon appears in these patients as fear of the death, fear of loneliness, and fear of disgrace. Due to the nature of the disease, these patients feel an inner fear of premature death, as soon as they receive a positive diagnosis. In this regard, the study of Audrey K Miller et al. [ 23 ] showed that death anxiety in AIDS patients is a psychological complication. the participants have stated that they are very afraid of being alone after receiving a positive diagnosis, which is a natural feeling according to Keith Cherry and David H. Smith [ 24 ]; because these patients will mainly experience some degree of loneliness. HIV-infected patients also experienced a fear of disgrace, which will go back to the nature of the disease and people’s insight; but they should be aware that, as Newman Amy states, AIDS/ HIV is a disease, not a scandal [ 25 ].

Another experience of the participants in dealing with the positive diagnosis of the disease is guilt feeling. The patients will experience feelings of regret, the feeling guilty and feeling of the conscience-stricken. The experience of the participants shows that they regret their past. Earlier studies have also revealed that regret for the past is a common phenomenon among the patients living with HIV [ 26 , 27 , 28 ]. HIV-infected feel guilty while facing the positive diagnosis of the disease and consider themselves the main culprit of the situation. They often play a direct role in their infection, and their past lifestyle for sure [ 29 ]. Our study also found that these patients feel the conscience-stricken after a positive diagnosis, because they suspect that they may have infected people around them. This disease can be easily transmitted from the carrier to others if the health protocols are not followed [ 30 , 31 , 32 ].

Another experience of HIV-infected in dealing with the receiving a positive diagnosis of the disease is discouragement. These patients are disappointed and sometimes decide to suicide. Based on the lived experience of HIV-infected, it was found that receiving a positive diagnosis of the disease, will discourage them from life and patients will be disappointed in many aspects of life. Studies have shown that AIDS/HIV, as a crisis, will greatly reduce the patients' life expectancy and that they will continue to live in despair [ 33 ]. Studies also stated that they considered suicide as a solution to relieve stress when receiving a positive diagnosis. In this regard, various studies have emphasized that among the AIDS/HIV patients, loss of self-esteem and severe stress have led to high suicide rates [ 34 , 35 , 36 ].

According to the patients, trying to escape from reality is another phenomenon that they will experience. This phenomenon will occur in patients as denial and trying to hide the disease from others. Based on the lived experience of these patients, it was found that after facing a positive diagnosis, HIV-infected tend to deny that they are infected. In this regard, various studies have shown that AIDS/HIV patients in different stages of the disease and their lives try to deny it in different ways [ 37 , 38 , 39 ]. The HIV-infected also stated that at the beginning of the positive diagnosis of the disease, did not want others to know, so they wanted to hide themselves from others in any way possible. In this regard, Emilie Henry et al. [ 40 ] have shown that a high percentage of the patients living with AIDS/HIV have tried that others do not notice that they are ill.

One of the strengths of this study is the methodology of the study, because in this study, an attempt has been made to use descriptive phenomenology to explain the lived experience of HIV-infected patients when faced with a positive diagnosis of this disease. In fact, in this study, patients' experience of this particular situation was identified, and with careful analysis, the experiences of these people became codes and concepts, each of which can be a bridge that keeps the path of modern knowledge open to help these patients. One of the limitations of this study is the generalizability of the findings because patients’ experiences in different societies that have cultural, religious, subsistence, and economic differences can be different.

The results of this study showed that patients will experience unpleasant experiences in the face of receiving a positive diagnosis of the HIV. Patients’ unpleasant experiences at that moment include emotional shock, fear of the consequences, feeling guilty, discouragement and escape from reality. Therefore, medical and laboratory centers must pay attention to the patients' lived experience, and try to support the patients through education, counseling and other support programs to minimize the psychological trauma caused by the disease.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors through reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Hamadan Health Network, the Hamadan Shohada Behavioral Diseases Counseling Center, and the participants who helped us in this study.

The study was funded by Vice-chancellor for Research and Technology, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences (No. 9812209934).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Operating Room, School of Paramedicine, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

Behzad Imani

Department of Operating Room, Student Research Committee, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

Shirdel Zandi

Research Center for Health Sciences, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

Salman khazaei

Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran

Mohamad Mirzaei

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

BI designed the study, collected the data, and provide the first draft of manuscript. ShZ designed the study and revised the manuscript. SKh participated in design of the study, the data collection, and revised the manuscript. MM participated in design of the study and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Shirdel Zandi .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study is the result of a student project that has been registered in Hamadan University of Medical Sciences of Iran with the ethical code IR.UMSHA.REC.1398.1000.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Imani, B., Zandi, S., khazaei, S. et al. The lived experience of HIV-infected patients in the face of a positive diagnosis of the disease: a phenomenological study. AIDS Res Ther 18 , 95 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-021-00421-4

Download citation

Received : 15 July 2021

Accepted : 26 November 2021

Published : 07 December 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-021-00421-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Lived experience

- Phenomenological study

AIDS Research and Therapy

ISSN: 1742-6405

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), is an ongoing, also called chronic, condition. It's caused by the human immunodeficiency virus, also called HIV. HIV damages the immune system so that the body is less able to fight infection and disease. If HIV isn't treated, it can take years before it weakens the immune system enough to become AIDS . Thanks to treatment, most people in the U.S. don't get AIDS .

HIV is spread through contact with genitals, such as during sex without a condom. This type of infection is called a sexually transmitted infection, also called an STI. HIV also is spread through contact with blood, such as when people share needles or syringes. It is also possible for a person with untreated HIV to spread the virus to a child during pregnancy, childbirth or breastfeeding.

There's no cure for HIV / AIDS . But medicines can control the infection and keep the disease from getting worse. Antiviral treatments for HIV have reduced AIDS deaths around the world. There's an ongoing effort to make ways to prevent and treat HIV / AIDS more available in resource-poor countries.

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Assortment of Pill Aids from Mayo Clinic Store

The symptoms of HIV and AIDS vary depending on the person and the phase of infection.

Primary infection, also called acute HIV

Some people infected by HIV get a flu-like illness within 2 to 4 weeks after the virus enters the body. This stage may last a few days to several weeks. Some people have no symptoms during this stage.

Possible symptoms include:

- Muscle aches and joint pain.

- Sore throat and painful mouth sores.

- Swollen lymph glands, also called nodes, mainly on the neck.

- Weight loss.

- Night sweats.

These symptoms can be so mild that you might not notice them. However, the amount of virus in your bloodstream, called viral load, is high at this time. As a result, the infection spreads to others more easily during primary infection than during the next stage.

Clinical latent infection, also called chronic HIV

In this stage of infection, HIV is still in the body and cells of the immune system, called white blood cells. But during this time, many people don't have symptoms or the infections that HIV can cause.

This stage can last for many years for people who aren't getting antiretroviral therapy, also called ART. Some people get more-severe disease much sooner.

Symptomatic HIV infection

As the virus continues to multiply and destroy immune cells, you may get mild infections or long-term symptoms such as:

- Swollen lymph glands, which are often one of the first symptoms of HIV infection.

- Oral yeast infection, also called thrush.

- Shingles, also called herpes zoster.

Progression to AIDS

Better antiviral treatments have greatly decreased deaths from AIDS worldwide. Thanks to these lifesaving treatments, most people with HIV in the U.S. today don't get AIDS . Untreated, HIV most often turns into AIDS in about 8 to 10 years.

Having AIDS means your immune system is very damaged. People with AIDS are more likely to develop diseases they wouldn't get if they had healthy immune systems. These are called opportunistic infections or opportunistic cancers. Some people get opportunistic infections during the acute stage of the disease.

The symptoms of some of these infections may include:

- Fever that keeps coming back.

- Ongoing diarrhea.

- Swollen lymph glands.

- Constant white spots or lesions on the tongue or in the mouth.

- Constant fatigue.

- Rapid weight loss.

- Skin rashes or bumps.

When to see a doctor

If you think you may have been infected with HIV or are at risk of contracting the virus, see a healthcare professional as soon as you can.

More Information

- Early HIV symptoms: What are they?

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

HIV is caused by a virus. It can spread through sexual contact, shooting of illicit drugs or use of shared needles, and contact with infected blood. It also can spread from parent to child during pregnancy, childbirth or breastfeeding.

HIV destroys white blood cells called CD4 T cells. These cells play a large role in helping the body fight disease. The fewer CD4 T cells you have, the weaker your immune system becomes.

How does HIV become AIDS?

You can have an HIV infection with few or no symptoms for years before it turns into AIDS . AIDS is diagnosed when the CD4 T cell count falls below 200 or you have a complication you get only if you have AIDS , such as a serious infection or cancer.

How HIV spreads

You can get infected with HIV if infected blood, semen or fluids from a vagina enter your body. This can happen when you:

- Have sex. You may become infected if you have vaginal or anal sex with an infected partner. Oral sex carries less risk. The virus can enter your body through mouth sores or small tears that can happen in the rectum or vagina during sex.

- Share needles to inject illicit drugs. Sharing needles and syringes that have been infected puts you at high risk of HIV and other infectious diseases, such as hepatitis.

- Have a blood transfusion. Sometimes the virus may be transmitted through blood from a donor. Hospitals and blood banks screen the blood supply for HIV . So this risk is small in places where these precautions are taken. The risk may be higher in resource-poor countries that are not able to screen all donated blood.

- Have a pregnancy, give birth or breastfeed. Pregnant people who have HIV can pass the virus to their babies. People who are HIV positive and get treatment for the infection during pregnancy can greatly lower the risk to their babies.

How HIV doesn't spread

You can't become infected with HIV through casual contact. That means you can't catch HIV or get AIDS by hugging, kissing, dancing or shaking hands with someone who has the infection.

HIV isn't spread through air, water or insect bites. You can't get HIV by donating blood.

Risk factors

Anyone of any age, race, sex or sexual orientation can have HIV / AIDS . However, you're at greatest risk of HIV / AIDS if you:

- Have unprotected sex. Use a new latex or polyurethane condom every time you have sex. Anal sex is riskier than is vaginal sex. Your risk of HIV increases if you have more than one sexual partner.

- Have an STI . Many STIs cause open sores on the genitals. These sores allow HIV to enter the body.

- Inject illicit drugs. If you share needles and syringes, you can be exposed to infected blood.

Complications

HIV infection weakens your immune system. The infection makes you much more likely to get many infections and certain types of cancers.

Infections common to HIV/AIDS

- Pneumocystis pneumonia, also called PCP. This fungal infection can cause severe illness. It doesn't happen as often in the U.S. because of treatments for HIV / AIDS . But PCP is still the most common cause of pneumonia in people infected with HIV .

- Candidiasis, also called thrush. Candidiasis is a common HIV -related infection. It causes a thick, white coating on the mouth, tongue, esophagus or vagina.

- Tuberculosis, also called TB. TB is a common opportunistic infection linked to HIV . Worldwide, TB is a leading cause of death among people with AIDS . It's less common in the U.S. thanks to the wide use of HIV medicines.

- Cytomegalovirus. This common herpes virus is passed in body fluids such as saliva, blood, urine, semen and breast milk. A healthy immune system makes the virus inactive, but it stays in the body. If the immune system weakens, the virus becomes active, causing damage to the eyes, digestive system, lungs or other organs.

- Cryptococcal meningitis. Meningitis is swelling and irritation, called inflammation, of the membranes and fluid around the brain and spinal cord, called meninges. Cryptococcal meningitis is a common central nervous system infection linked to HIV . A fungus found in soil causes it.

Toxoplasmosis. This infection is caused by Toxoplasma gondii, a parasite spread primarily by cats. Infected cats pass the parasites in their stools. The parasites then can spread to other animals and humans.

Toxoplasmosis can cause heart disease. Seizures happen when it spreads to the brain. And it can be fatal.

Cancers common to HIV/AIDS

- Lymphoma. This cancer starts in the white blood cells. The most common early sign is painless swelling of the lymph nodes most often in the neck, armpit or groin.

- Kaposi sarcoma. This is a tumor of the blood vessel walls. Kaposi sarcoma most often appears as pink, red or purple sores called lesions on the skin and in the mouth in people with white skin. In people with Black or brown skin, the lesions may look dark brown or black. Kaposi sarcoma also can affect the internal organs, including the lungs and organs in the digestive system.

- Human papillomavirus (HPV)-related cancers. These are cancers caused by HPV infection. They include anal, oral and cervical cancers.

Other complications

- Wasting syndrome. Untreated HIV / AIDS can cause a great deal of weight loss. Diarrhea, weakness and fever often happen with the weight loss.

- Brain and nervous system, called neurological, complications. HIV can cause neurological symptoms such as confusion, forgetfulness, depression, anxiety and difficulty walking. HIV -associated neurological conditions can range from mild symptoms of behavior changes and reduced mental functioning to severe dementia causing weakness and not being able to function.

- Kidney disease. HIV -associated nephropathy (HIVAN) is swelling and irritation, called inflammation, of the tiny filters in the kidneys. These filters remove excess fluid and waste from the blood and pass them to the urine. Kidney disease most often affects Black and Hispanic people.

- Liver disease. Liver disease also is a major complication, mainly in people who also have hepatitis B or hepatitis C.

There's no vaccine to prevent HIV infection and no cure for HIV / AIDS . But you can protect yourself and others from infection.

To help prevent the spread of HIV :

Consider preexposure prophylaxis, also called PrEP. There are two PrEP medicines taken by mouth, also called oral, and one PrEP medicine given in the form of a shot, called injectable. The oral medicines are emtricitabine-tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (Truvada) and emtricitabine-tenofovir alafenamide fumarate (Descovy). The injectable medicine is called cabotegravir (Apretude). PrEP can reduce the risk of sexually transmitted HIV infection in people at very high risk.

PrEP can reduce the risk of getting HIV from sex by about 99% and from injecting drugs by at least 74%, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Descovy hasn't been studied in people who have sex by having a penis put into their vaginas, called receptive vaginal sex.

Cabotegravir (Apretude) is the first U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved PrEP that can be given as a shot to reduce the risk of sexually transmitted HIV infection in people at very high risk. A healthcare professional gives the shot. After two once-monthly shots, Apretude is given every two months. The shot is an option in place of a daily PrEP pill.

Your healthcare professional prescribes these medicines to prevent HIV only to people who don't already have HIV infection. You need an HIV test before you start taking any PrEP . You need to take the test every three months for the pills or before each shot for as long as you take PrEP .

You need to take the pills every day or closely follow the shot schedule. You still need to practice safe sex to protect against other STIs . If you have hepatitis B, you should see an infectious disease or liver specialist before beginning PrEP therapy.

Use treatment as prevention, also called TasP. If you have HIV , taking HIV medicines can keep your partner from getting infected with the virus. If your blood tests show no virus, that means your viral load can't be detected. Then you won't transmit the virus to anyone else through sex.

If you use TasP , you must take your medicines exactly as prescribed and get regular checkups.

- Use post-exposure prophylaxis, also called PEP, if you've been exposed to HIV . If you think you've been exposed through sex, through needles or in the workplace, contact your healthcare professional or go to an emergency room. Taking PEP as soon as you can within the first 72 hours can greatly reduce your risk of getting HIV . You need to take the medicine for 28 days.

Use a new condom every time you have anal or vaginal sex. Both male and female condoms are available. If you use a lubricant, make sure it's water based. Oil-based lubricants can weaken condoms and cause them to break.

During oral sex, use a cut-open condom or a piece of medical-grade latex called a dental dam without a lubricant.

- Tell your sexual partners you have HIV . It's important to tell all your current and past sexual partners that you're HIV positive. They need to be tested.

- Use clean needles. If you use needles to inject illicit drugs, make sure the needles are sterile. Don't share them. Use needle-exchange programs in your community. Seek help for your drug use.

- If you're pregnant, get medical care right away. You can pass HIV to your baby. But if you get treatment during pregnancy, you can lessen your baby's risk greatly.

- Consider male circumcision. Studies show that removing the foreskin from the penis, called circumcision, can help reduce the risk of getting HIV infection.

- About HIV and AIDS . HIV.gov. https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/overview/about-hiv-and-aids/what-are-hiv-and-aids. Accessed Oct. 18, 2023.

- Sax PE. Acute and early HIV infection: Clinical manifestations and diagnosis. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Oct. 18, 2023.

- Ferri FF. Human immunodeficiency virus. In: Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2024. Elsevier; 2024. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed Oct. 18, 2023.

- Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV . HIV.gov. https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infections/immunizations. Accessed Oct. 18, 2023.

- AskMayoExpert. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Mayo Clinic; 2023.

- Elsevier Point of Care. Clinical Overview: HIV infection and AIDS in adults. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed Oct. 18, 2023.

- Male circumcision for HIV prevention fact sheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/fact-sheets/hiv/male-circumcision-HIV-prevention-factsheet.html. Accessed Oct. 19, 2023.

- Acetyl-L-carnitine. Natural Medicines. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com. Accessed. Oct. 19, 2023.

- Whey protein. Natural Medicines. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com. Accessed. Oct. 19, 2023.

- Saccharomyces boulardii. Natural Medicines. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com. Accessed Oct. 19, 2023.

- Vitamin A. Natural Medicines. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com. Accessed Oct. 19, 2023.

- Red yeast rice. Natural Medicines. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com. Accessed Oct. 19, 2023.

Associated Procedures

- Liver function tests

News from Mayo Clinic

- Unlocking the mechanisms of HIV in preclinical research Jan. 10, 2024, 03:30 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic expert on future of HIV on World AIDS Day Dec. 01, 2023, 05:15 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Know your status -- the importance of HIV testing June 27, 2023, 03:00 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic Q&A podcast: The importance of HIV testing June 24, 2022, 12:18 p.m. CDT

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

- Doctors & departments

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

- What Are HIV and AIDS?

- How Is HIV Transmitted?

- Who Is at Risk for HIV?

Symptoms of HIV

- U.S. Statistics

- Impact on Racial and Ethnic Minorities

- Global Statistics

- HIV and AIDS Timeline

- In Memoriam

- Supporting Someone Living with HIV

- Standing Up to Stigma

- Getting Involved

- HIV Treatment as Prevention

- Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP)

- Post-exposure Prophylaxis (PEP)

- Preventing Sexual Transmission of HIV

- Alcohol and HIV Risk

- Substance Use and HIV Risk

- Preventing Perinatal Transmission of HIV

- HIV Vaccines

- Long-acting HIV Prevention Tools

- Microbicides

- Who Should Get Tested?

- HIV Testing Locations

- HIV Testing Overview

- Understanding Your HIV Test Results

- Living with HIV

- Talking About Your HIV Status

- Locate an HIV Care Provider

- Types of Providers

- Take Charge of Your Care

- What to Expect at Your First HIV Care Visit

- Making Care Work for You

- Seeing Your Health Care Provider

- HIV Lab Tests and Results

- Returning to Care

- HIV Treatment Overview

- Viral Suppression and Undetectable Viral Load

- Taking Your HIV Medicine as Prescribed

- Tips on Taking Your HIV Medication Every Day

- Paying for HIV Care and Treatment

- Other Health Issues of Special Concern for People Living with HIV

- Alcohol and Drug Use

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) and People with HIV

- Hepatitis B & C

- Vaccines and People with HIV

- Flu and People with HIV

- Mental Health

- Mpox and People with HIV

- Opportunistic Infections

- Sexually Transmitted Infections

- Syphilis and People with HIV

- HIV and Women's Health Issues

- Aging with HIV

- Emergencies and Disasters and HIV

- Employment and Health

- Exercise and Physical Activity

- Food Safety and Nutrition

- Housing and Health

- Traveling Outside the U.S.

- Civil Rights

- Workplace Rights

- Limits on Confidentiality

- National HIV/AIDS Strategy (2022-2025)

- Implementing the National HIV/AIDS Strategy

- Prior National HIV/AIDS Strategies (2010-2021)

- Key Strategies

- Priority Jurisdictions

- HHS Agencies Involved

- Learn More About EHE

- Ready, Set, PrEP

- Ready, Set, PrEP Pharmacies

- Ready, Set, PrEP Resources

- AHEAD: America’s HIV Epidemic Analysis Dashboard

- HIV Prevention Activities

- HIV Testing Activities

- HIV Care and Treatment Activities

- HIV Research Activities

- Activities Combating HIV Stigma and Discrimination

- The Affordable Care Act and HIV/AIDS

- HIV Care Continuum

- Syringe Services Programs

- Finding Federal Funding for HIV Programs

- Fund Activities

- The Fund in Action

- About PACHA

- Members & Staff

- Subcommittees

- Prior PACHA Meetings and Recommendations

- I Am a Work of Art Campaign

- Awareness Campaigns

- Global HIV/AIDS Overview

- U.S. Government Global HIV/AIDS Activities

- U.S. Government Global-Domestic Bidirectional HIV Work

- Global HIV/AIDS Organizations

- National Black HIV/AIDS Awareness Day February 7

- HIV Is Not A Crime Awareness Day February 28

- National Women and Girls HIV/AIDS Awareness Day March 10

- National Native HIV/AIDS Awareness Day March 20

- National Youth HIV & AIDS Awareness Day April 10

- HIV Vaccine Awareness Day May 18

- National Asian & Pacific Islander HIV/AIDS Awareness Day May 19

- HIV Long-Term Survivors Awareness Day June 5

- National HIV Testing Day June 27

- Zero HIV Stigma July 21

- Southern HIV/AIDS Awareness Day August 20

- National Faith HIV/AIDS Awareness Day August 27

- National African Immigrants and Refugee HIV/AIDS and Hepatitis Awareness Day September 9

- National HIV/AIDS and Aging Awareness Day September 18

- National Gay Men's HIV/AIDS Awareness Day September 27

- National Latinx AIDS Awareness Day October 15

- World AIDS Day December 1

- Event Planning Guide

- U.S. Conference on HIV/AIDS (USCHA)

- National Ryan White Conference on HIV Care & Treatment

- AIDS 2020 (23rd International AIDS Conference Virtual)

Want to stay abreast of changes in prevention, care, treatment or research or other public health arenas that affect our collective response to the HIV epidemic? Or are you new to this field?

HIV.gov curates learning opportunities for you, and the people you serve and collaborate with.

Stay up to date with the webinars, Twitter chats, conferences and more in this section.

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share on Email

How Can You Tell If You Have HIV?

The only way to know for sure if you have HIV is to get tested. You can’t rely on symptoms to tell whether you have HIV.

Knowing your HIV status gives you powerful information so you can take steps to keep yourself and your partner(s) healthy:

- If you test positive , you can take medicine to treat HIV. People with HIV who take HIV medicine (called antiretroviral therapy or ART) as prescribed and get and keep an undetectable viral load can live long and healthy lives and will not transmit HIV to their HIV-negative partners through sex . An undetectable viral load is a level of HIV in the blood so low that it can’t be detected in a standard lab test.

- If you test negative , you have more HIV prevention tools available today than ever before, like pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) , medicine people at risk for HIV take to prevent getting HIV from sex or injection drug use, and post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP ), HIV medicine taken within 72 hours after a possible exposure to prevent the virus from taking hold.

- If you are pregnant , you should be tested for HIV so that you can begin treatment if you're HIV-positive. If you have HIV and take HIV medicine as prescribed throughout your pregnancy and childbirth and give HIV medicine to your baby for 4 to 6 weeks after giving birth, your risk of transmitting HIV to your baby can be less than 1%. HIV medicine will protect your own health as well.

Use the HIV Services Locator to find an HIV testing site near you.

HIV self-testing is also an option. Self-testing allows people to take an HIV test and find out their result in their own home or other private location. You can buy a self-test kit at a pharmacy or online, or your health care provider may be able to order one for you. Some health departments or community-based organizations also provide self-test kits for a reduced cost or for free. Learn more about HIV self-testing and which test might be right for you .

What Are the Symptoms of HIV?

There are several symptoms of HIV. Not everyone will have the same symptoms. It depends on the person and what stage of the disease they are in.

Below are the three stages of HIV and some of the symptoms people may experience.

Stage 1: Acute HIV Infection

Within 2 to 4 weeks after infection with HIV, about two-thirds of people will have a flu-like illness. This is the body’s natural response to HIV infection.

Flu-like symptoms can include:

- Night sweats

- Muscle aches

- Sore throat

- Swollen lymph nodes

- Mouth ulcers

These symptoms can last anywhere from a few days to several weeks. But some people do not have any symptoms at all during this early stage of HIV.

Don’t assume you have HIV just because you have any of these symptoms—they can be similar to those caused by other illnesses. But if you think you may have been exposed to HIV, get an HIV test.

Here’s what to do:

- Find an HIV testing site near you —You can get an HIV test at your primary care provider’s office, your local health department, a health clinic, or many other places . Use the HIV Services Locator to find an HIV testing site near you.

- Request an HIV test for recent infection —Most HIV tests detect antibodies (proteins your body makes as a reaction to HIV), not HIV itself. But it can take a few weeks after you have HIV for your body to produce these antibodies. There are other types of tests that can detect HIV infection sooner. Tell your doctor or clinic if you think you were recently exposed to HIV and ask if their tests can detect early infection.

- Know your status —After you get tested, be sure to learn your test results. If you’re HIV-positive, see a health care provider as soon as possible so you can start treatment with HIV medicine. And be aware: when you are in the early stage of infection, you are at very high risk of transmitting HIV to others. It is important to take steps to reduce your risk of transmission. If you are HIV-negative, there are prevention tools like pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) that can help you stay negative.

Stage 2: Clinical Latency

In this stage, the virus still multiplies, but at very low levels. People in this stage may not feel sick or have any symptoms. This stage is also called chronic HIV infection .

Without HIV treatment, people can stay in this stage for 10 or 15 years, but some move through this stage faster.

If you take HIV medicine exactly as prescribed and get and keep an undetectable viral load, you can live and long and healthy life and will not transmit HIV to your HIV-negative partners through sex.

But if your viral load is detectable, you can transmit HIV during this stage, even when you have no symptoms. It’s important to see your health care provider regularly to get your viral load checked.

Stage 3: AIDS

If you have HIV and you are not on HIV treatment, eventually the virus will weaken your body’s immune system and you will progress to AIDS ( acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) .

This is the late stage of HIV infection.

Symptoms of AIDS can include:

- Rapid weight loss

- Recurring fever or profuse night sweats

- Extreme and unexplained tiredness

- Prolonged swelling of the lymph glands in the armpits, groin, or neck

- Diarrhea that lasts for more than a week

- Sores of the mouth, anus, or genitals

- Red, brown, pink, or purplish blotches on or under the skin or inside the mouth, nose, or eyelids

- Memory loss, depression, and other neurologic disorders

Each of these symptoms can also be related to other illnesses. The only way to know for sure if you have HIV is to get tested. If you are HIV-positive, a health care provider will diagnose if your HIV has progressed to stage 3 (AIDS) based on certain medical criteria .

Many of the severe symptoms and illnesses of HIV disease come from the opportunistic infections that occur because your body’s immune system has been damaged. See your health care provider if you are experiencing any of these symptoms.

But be aware: Thanks to effective treatment, most people in the U.S. with HIV do not progress to AIDS. If you have HIV and remain in care, take HIV medicine as prescribed, and get and keep an undetectable viral load, you will stay healthy and will not progress to AIDS.

Read more about the difference between HIV and AIDS .

Related HIV.gov Blogs

- Testing HIV Testing

- Self-Testing HIV Self-Testing

- CDC – HIV Basics: How Do I Know If I Have HIV?

- NICHD – Symptoms of HIV/AIDS

- VA – HIV/AIDS Basics: Symptoms

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 18 March 2022

Experiences of new diagnoses among HIV-positive persons: implications for public health

- Adobea Yaa Owusu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2223-7896 1

BMC Public Health volume 22 , Article number: 538 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

2876 Accesses

4 Citations

Metrics details

Ready acceptance of experiences of new diagnoses among HIV-positive persons is a known personal and public health safety-net. Its beneficial effects include prompt commencement and sustenance of HIV-positive treatment and care, better management of transmission risk, and disclosure of the HIV-positive status to significant others. Yet, no known study has explored this topic in Ghana; despite Ghana’s generalised HIV/AIDS infection rate. Existing studies have illuminated the effects of such reactions on affected significant others; not the infected.

This paper studied qualitatively the experiences of new diagnoses among 26 persons living with HIV/AIDS. Sample selection was random, from two hospitals in a district in Ghana heavily affected by HIV/AIDS. The paper applied the Hopelessness Theory of Depression.

As expected, the vast majority of respondents experienced the new diagnoses of their HIV-positive infection with a myriad of negative psychosocial reactions, including thoughts of committing suicide. Yet, few of them received the news with resignation. For the vast majority of respondents, having comorbidities from AIDS prior to the diagnosis primarily shaped their initial reactions to their diagnosis. The respondents’ transitioning to self-acceptance of their HIV-positive status was mostly facilitated by receiving counselling from healthcare workers.

Conclusions

Although the new HIV-positive diagnosis was immobilising to most respondents, the trauma faded, paving the way for beneficial public health actions. The results imply the critical need for continuous education on HIV/AIDS by public health advocates, using mass media, particularly, TV. Healthcare workers in VCTs should empathise with persons who experience new diagnoses of their HIV-positive status.

Peer Review reports

News of a newly-diagnosed HIV-positive status has the tendency to lead to negative psychosocial outcomes for persons living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHAs) [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. In this paper, the concept of newly-diagnosed refers to the first time a respondent was informed of his/her HIV-positive status. Implications of this operational definition are discussed later on in the paper. Humans depict cognitive, emotional, and motivational deficits on hearing bad news and experiencing what is deemed uncontrollable events [ 4 ]. This is very likely to apply to PLWHAs particularly, when confronted with the news of being HIV-positive for the first time. Particularly, PLWHAs are known to mostly experience neurocognitive disorders associated with the infection [ 5 ], and often experience common mental disorders [ 6 , 7 ]. This is especially the case when PLWHAs fairly expect or self-perceive negative social reactions such as spousal abuse, dismissal from employment, stigma and discrimination, among others [ 8 ]. Peterson and Seligman ([ 4 ], p. 347) christened these series of responses on such occasions as “learned helplessness phenomenon.”

There are numerous news reports of persons who have committed suicide shortly after an HIV-positive diagnosis. This includes even the case of a female physician from the Eket local government area of Akwa Ibom, Nigeria [ 9 ]. Previous researchers note that after the initial diagnosis of a disease believed to be life-threatening, and particularly incurable, patients are known to experience an immediate descent into several distressing psychological and emotional states of mind [ 1 , 2 , 10 ]. These range from disbelief to denial to being utterly scared and shocked. Some even think that their life is not worth living anymore and imagine that indeed, the disease has already taken a final toll on them [ 2 , 3 ]. This brings to the fore the need to study the reactions of PLWHAs right after their initial diagnosis. Research and programme interventions on adaptation to a new HIV diagnosis provide personal and public health safety-nets and are thus needed [ 2 , 11 ]. Such research and interventions are helpful in educating newly-diagnosed PLWHAs on HIV [ 1 , 10 ] and promoting their health [ 1 , 8 , 12 ].

Acceptance of the news of an HIV-positive diagnosis is critical for several reasons [ 2 ]. Engagement in and sustenance of HIV treatment and care [ 1 , 2 ], viral load (VL), CD4 counts [ 2 , 13 ], and transmission risk [ 2 , 11 , 14 ] are affected by the reaction to the news of diagnosis. Reactions also affect perceptions of stigma and disclosure activity [ 2 , 11 ]. Conversely, difficulties with accepting diagnosed HIV-positive status has serious potential negative consequences for individuals and the general public [ 15 , 16 ]. From the angle of healthcare practitioners, better handling of new diagnosis of an HIV-positive status and related disclosure could greatly buffer the psychosocial and mental health of the newly-diagnosed PLWHAs, and help facilitate healthcare seeking and retention. These include the management of less traumatised disclosure, reduction of self-stigmatisation, and better management of romantic and family relationships [ 2 , 14 ]. Others are the reduction of viral transmission [ 14 , 17 ], and improvement in general public health and well-being of populations [ 1 , 14 ]. Knowing the experiences of new diagnoses among HIV-positive persons is, therefore, likely to facilitate successful linkage and retention of such persons in healthcare for HIV [ 1 , 2 ]. This is critical and is also known to be a significant gap in the HIV care continuum in some parts of the world, even the U.S. with all its known medical advancement [ 11 ].

Based on previous related literature, this paper primarily examines qualitatively the experiences of new diagnoses of 26 Ghanaian PLWHAs to the first news of their HIV-positive status. Second, it attempts to untangle the situations surrounding these experiences to determine what might have influenced such reactions. Third, the paper delineates the processes that particularly helped the PLWHAs transition from negative psychological reactions to showing positive reactions and seeking HIV treatment. Fourth, it adds to the core literature on managing experiences of new diagnoses of an HIV-positive status, and illuminates their importance to public health. It is hoped that this paper will facilitate a better acceptance of an HIV-positive sense of self which is known to aid PLWHAs to accept, adjust, and more effectively cope with their diagnosis. This will aid them to better manage the complexities of living with the infection [ 2 , 18 ]. This paper specifies the knowledge to Ghana and more importantly, Ghana’s most HIV/AIDS-affected district [ 19 , 20 ]. A thorough search on the experiences of PLWHAs’ new diagnoses in Ghana yielded no known results despite the fact that Ghana has a generalised HIV/AIDS epidemic: more than 1% of the residents have the infection [ 21 ]. This paper aims to fill that gap.

Immediate reactions to news of HIV positive status in Africa

The literature on the immediate reactions to the initial diagnosis of HIV-positive status is also sparse, and a majority of what research there is comes from South Africa. Such findings overwhelmingly corroborate each other: immediately after being diagnosed HIV-positive, PLWHAs studied depict deep negative emotions. Visser et al. [ 22 ] studied the phenomenon in South Africa, using a semi-structured interview of 293 pregnant women who were undergoing HIV test during antenatal care. On hearing the news, those who tested positive were shocked, and got frightened that they would be abandoned and discriminated against.

Fabianova [ 23 ] undertook a longitudinal study in Nairobi, Kenya, on the psychosocial aspects of being PLWHA. When the respondents who visited VCTs were first informed of their HIV-positive status, 89% of them felt sad due to their HIV-positive status, 60% had feelings of fear and anxiety, 30% felt angry, 25% felt distressed, and 15% cried. Additional psychosocial behaviours exhibited by the respondents included grief, guilt, hopelessness, helplessness, anger, disbelief, self-blame or blamed others, and aggression towards a counsellor. Their sadness was mostly in reference to close relatives who had died of AIDS. Their fears related mostly to the loss of their social position. Other fears surrounded loss of life, ambition, sexual relations, independence, physical performance, and financial stability [ 23 ]. While Fabianova [ 23 ] observed from the extant literature that suicide is a common reaction for persons who are first informed of their HIV/AIDS status, her study found that less than 1% of participants attempted suicide on hearing of their confirmed HIV-positive status. Most of Fabianova’s ([ 23 ], p. 201) respondents already considered themselves to be “walking corpses” and even visualised their funeral and grave.

Fabianova [ 23 ] enumerated several explanatory factors that unpacked her respondents’ reactions to their initial diagnoses of being HIV-positive. These included gender, level of preparedness of a client in the pre-testing session, and type of sexual relationship(s) they were in. Others included levels of general knowledge of HIV/AIDS, and HIV/AIDS-related stigma in their community. Fabianova ([ 23 ], p. 199) discovered that males responded to the initial HIV/AIDS diagnosis with anger, disbelief, and aggression. The females cried, got shocked, “swallowed big lumps of air, saliva subconsciously, shook both their hands in refusal and blame [sic] the others almost immediately.”

Other key explanatory factors for Fabianova’s ([ 23 ], p. 199) respondents’ immediate reactions included concerns about “lack of immediate elaborate support structures”, extent of level of awareness about HIV/AIDS, level of HIV/AIDS-related stigma, availability of antiretroviral therapy (ART), and support groups to enable them move on with their lives. Feelings of guilt for the infection were explained by whether the individual felt his/her lifestyle exposed him/her to it, and type of sexual involvement they were engaged in. They felt guilty that they would infect a spouse if they were married. If they were in an unstable/non-married relationship, they did not feel guilty, and shared the blame with the casual sexual partner. Sixty-two percent blamed their partners or the environment with the excuse that they stayed loyal to their partners. Fabianova’s ([ 23 ], p. 200) respondents who tested on their own volition did so based on their own or a partner’s “failure”, poor health or “accidental happening”, or work commitments.

The theoretical framework adopted for this paper, the Hopelessness Theory of Depression, is grounded on depression. Depression is currently one of the five leading causes of the disease burden internationally, except in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) [ 24 ]. Researchers note that depressive disorders and other common mental health disorders (CMDs--depression, anxiety and somatization) were critically linked to the Millennium Development Goals, particularly gender equity, poverty, HIV/AIDS, and maternal and child health [ 24 , 25 ]. Importantly, depression is the most diagnosed psychiatric disorder among PLWHAs. Depression also serves as a risk factor for the progression of HIV/AIDS. In African settings, a growing appreciation of an important link between CMDs and HIV/AIDS has been established [ 7 , 23 ] as well. HIV has unleashed “a significant strain” on mental health in Africa ([ 24 ], p. 61; [ 26 ]). The huge burden of HIV/AIDS in SSA accounts for 16% of depression in the sub-region [ 24 ]. Alternatively, a neurobiological association exists between HIV and CMDs: “the HIV virus has quite specific detrimental effects on neuronal function” ([ 24 ], pp. 61 & 65). Evidence-based reports in African settings and other developing nations (studies conducted in Sao Paulo, Bangkok, Kinshasa, Nairobi, and Ethiopia), found both more symptoms and a higher prevalence of depression among symptomatic PLWHAs than among non-symptomatic or HIV-negative persons [ 24 ].

Theoretical framework: the hopelessness theory of depression

The Hopelessness Theory of Depression is applied to this paper. It is a diathesis-stress theory which posits that organisms express some form of cognitive and emotional deficits after experiencing a bad event. The theory argues that three depressogenic inferential styles serve as risk factors of depression [ 27 , 28 ]. These are the tendency to attribute a bad event to a global or stable cause; the tendency to perceive bad events as having many disastrous consequences; and the propensity to view oneself as flawed or inefficient [ 28 , 29 ]. Making negative inference upsurges the possibility of hopelessness while feeling hopeless makes depression inevitable. With this explanation, the theory assumes hopelessness as a critical underlying factor to depression. Adding to the causal explanation, Seligman [ 30 ] stated that the symptoms, cure and prevention of a bad event also model depression. In societies like Ghana, where HIV is associated with nonconformity to societal expectations and/or sexual promiscuity, PLWHAs may be more exposed to adverse emotional and cognitive symptoms after receiving an HIV-positive report.

The application of the thesis of the Hopelessness Theory of Depression to HIV-positive populations in SSA is not new. Govender and Schlebusch’s [ 31 ] study in Kwa-Zulu Natal, South Africa, applied Beck’s Hopelessness Scale and Beck’s Depression Inventory [ 32 ] to their assessment of the correlation between depression, hopelessness, and suicidal thoughts in PLWHAs. Schlebusch and Govender [ 33 ] used the same inventories to study PLWHAs in a University-affiliated hospital in South Africa. Primarily, they studied the prevalence of risk of suicidal ideation in PLWHAs immediately after their first diagnosis. Kylmä et al. [ 34 ] also studied the full gamut/dynamics of the concept of hope (hope, despair, hopelessness) among PLWHAs. Their study yielded information on how PLWHAs’ perceptions of hope could facilitate their clinical care. The Hopelessness Theory of Depression is applied to the discussion of the findings.

Study setting and cultural context of LMKM

The LMKM, the catchment area for the study, is situated in the Eastern Region of Ghana. The region, one of ten at the time of data collection, had 2,633,154 residents by Ghana’s last Population and Housing census of 2010, making it the third most-populated region. The Eastern Region is mostly semi-urban [ 35 ]. The LMKM, one of 26 administrative municipalities/districts in the Eastern Region by the time of data collection, covers 12.4% of the region, with total land mass of 304.4 km 2 . The 2010 Population and Housing Census recorded 89,246 residents of the Municipality comprising 46.5% males and 53.5% females. Christians were 92.8%; other religious groups include Muslims and traditionalists [ 36 ]. The indigenes are ethnic Dangmes and speak Krobo. They are a patrilineal descent group, which means they inherit property through their father’s lineage.

Sampling and data collection

This study used a “descriptive, multiple case study approach” ([ 2 ], p. 2; [ 37 ]). This method generates interviewees’ in-depth descriptions of their situations, views and realities regarding issues. This provides deep insights of their actions and choices [ 38 ]. In this study, the pool of cases of the individual respondents is considered a “multiple case study approach” ([ 2 , p. 2; 37 ]). Additionally, the findings from the study municipality forms a case study. As Kutnick et al. [ 2 ] note, case studies are exceptionally useful in eliciting contextual situations, when they are important to a particular study. Examples are cultural, social and structural impediments (such as stigma, and fear) to post-diagnosis HIV care [ 37 ].

This paper analysed data from 26 (13 each from two hospitals studied) out of 38 PLWHAs interviewed qualitatively through personal interviews from June to July 2015. The data used for this study formed part of a large data set from a project which primarily studied the linkages between housing conditions and the reported health status of PLWHAs (see [ 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 ]). The implications of recruiting individuals further away from their diagnosis for this paper are addressed in the section on limitations. The interviews were conducted with the aid of a pretested semi-structured question guide. Table 1 has the key questions asked. Some of these key questions in Table 1 were probing questions that emanated from the main/initial interview guide, because it is open ended, as is the norm with data collection tools for qualitative studies. The initial sample of 38 comprised both males and females who were selected using random sampling [ 2 ] as part of a research project which primarily studied the nexus between the health status of PLWHAs in the LMKM and their housing conditions.