- Data, AI, & Machine Learning

- Managing Technology

- Social Responsibility

- Workplace, Teams, & Culture

- AI & Machine Learning

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Big ideas Research Projects

- Artificial Intelligence and Business Strategy

- Responsible AI

- Future of the Workforce

- Future of Leadership

- All Research Projects

- AI in Action

- Most Popular

- The Truth Behind the Nursing Crisis

- Work/23: The Big Shift

- Coaching for the Future-Forward Leader

- Measuring Culture

The spring 2024 issue’s special report looks at how to take advantage of market opportunities in the digital space, and provides advice on building culture and friendships at work; maximizing the benefits of LLMs, corporate venture capital initiatives, and innovation contests; and scaling automation and digital health platform.

- Past Issues

- Upcoming Events

- Video Archive

- Me, Myself, and AI

- Three Big Points

The Real Lessons From Kodak’s Decline

Eastman kodak is often mischaracterized as a company whose managers didn’t recognize soon enough that digital technology would decimate its traditional business. however, what really happened at kodak is much more complicated — and instructive..

- Leading Change

- Business Models

- Developing Strategy

- Technology Innovation Strategy

Eastman Kodak Co. is often cited as an iconic example of a company that failed to grasp the significance of a technological transition that threatened its business. After decades of being an undisputed world leader in film photography, Kodak built the first digital camera back in 1975. But then, the story goes, the company couldn’t see the fundamental shift (in its particular case, from analog to digital technology) that was happening right under its nose.

The big problem with this version of events is that it’s wrong. Moreover, it obscures some important lessons that other companies can learn from. To begin with, senior leaders at Kodak were acutely aware of the approaching storm. I know because I arrived at Kodak from Silicon Valley in mid-1997, just as digital photography was taking off. Management was constantly tracking the rate at which digital media was replacing film. But several factors made it exceedingly difficult for Kodak to shift gears and emerge with a consumer franchise that would be sustainable over the long term. Not only was a major technological change upending our competitive landscape; challenges were also affecting the ecosystem we operated in and our organizational model. Ultimately, refocusing the business with so many forces in motion proved to be impossible.

A Difficult Technology Transition

Kodak’s first challenge had to do with technology. Over the course of more than a century, Kodak and a small number of its competitors had developed and refined manufacturing processes that enabled consumers to capture and preserve images for a lifetime. Color film was an extremely complex product to manufacture. The 60-inch “wide rolls” of plastic base material had to be coated with as many as 24 layers of sophisticated chemicals: photosensitizers, dyes, couplers, and other materials deposited at precise thicknesses while traveling at 300 feet per minute. Wide rolls had to be changed over and spliced continuously in real time; the coated film had to be cut to size and packaged — all in the dark. With film, the entry barriers were high. Only two competitors — Fujifilm and Agfa-Gevaert — had enough expertise and production scale to challenge Kodak seriously.

The transition from analog to digital imaging brought several challenges. First, digital imaging was based on a general-purpose semiconductor technology platform that had nothing to do with film manufacturing — it had its own scale and learning curves. The broad applicability of the technology platform meant that it could be scaled up in numerous high-volume markets (such as microprocessors, logic circuits, and communications chips) apart from digital imaging. Suppliers selling components offered the technology to anyone who would pay, and there were few entry barriers. What’s more, digital technology is modular. A good engineer could buy all the building blocks and put together a camera. These building blocks abstracted almost all the technology required, so you no longer needed a lot of experience and specialized skills.

Semiconductor technology was well outside of Kodak’s core know-how and organizational capabilities. Even though the company invested lots of money in the basic research and manufacturing of solid-state semiconductor image sensors and developed some notable inventions (including the color filter array that is used on virtually every color image sensor), it had little hope of being a competitive volume supplier of image sensor components, and it was difficult for Kodak to offer something distinctive. Contrast this with Sony Corp., which entered the sensor business to support its electronic video recording business. As an electronics company, its organizational capabilities were far more aligned with what was needed to succeed. What’s more, it jumped in early.

But Sony and other Japanese consumer electronic companies also had to adjust to the changes brought on by digital technology. Sony’s Trinitron color television, once a category leader, was overrun by “plug-and-play” modular digital components — in this case, liquid crystal displays, flat panel displays, and TV chips that made designing a television set easier. As Yukio Shohtoku, retired executive vice president of Panasonic Corp. explained to me, modularization “makes consumer products, our consumer products, a commodity.”

Once consumer electronic products transitioned to digital, Shohtoku noted, leading brands such as Panasonic and Sony lost their competitive edge in those markets. This explains how hundreds of companies, many of them startups, could move into imaging and how a company such as GoPro Inc., based in San Mateo, California, could appear out of nowhere and take the consumer video recorder market by storm. It’s a situation that many makers of technology products are now facing or may soon face.

Scaling Down Is Hard

While the technology presented one set of problems, figuring out how to manage declining film sales while trying to extract maximum profits presented another. Growing companies learn how to invest in manufacturing efficiency and in achieving scale economies. As volumes increase, unit costs go down and capital efficiency improves. But scaling down is hard to do. It helps if your capital base is fully depreciated, but what if you have to reduce the size of your production runs? At a certain point, you just don’t have enough volume anymore to absorb your fixed costs.

In Kodak’s case, film had a finite shelf life, so as sales declined, the company had to figure out how to shrink the size of production batches without driving unit costs up too far or forcing the selling price up, which would have led to a death spiral. I remember when the yearly sales of a particular type of Kodak film went below a single wide, roll production batch. Shrinking the run length would drive up the proportion of time and materials expended in setup, and shifting to smaller production lines would incur additional capital expense, something that would have been impossible to justify. Having a product line made up of many film types worked well when sales were going up but worked against the company as volumes shrank. Discontinuing products pushed film photographers (especially professionals) to digital, and it further drove down cost absorption. For a while, Kodak was fortunate that motion picture print film manufacturing was able to absorb a huge proportion of factory overhead. But when theaters finally moved to digital projection, the company couldn’t slash costs fast enough to keep up with declining volumes.

Declining scale was also a big problem for Kodak in its retail distribution network. Once the volume of film sales at retail stores started to drop, holding onto shelf space became harder. This is not a unique problem — it happens in other markets that are being affected by low-cost imports, market fragmentation, or the cyclical decline of products as newer, more sophisticated products are introduced. But in Kodak’s case, the category was disappearing. For many years, Kodak management was careful not to talk about the problem publicly to prevent it from becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy (something critics misconstrued as management not grasping the gravity of the situation). One could argue that exiting the business and forcing consumers to transition to new solutions was the right way to go. But that would have required Kodak to give up billions of dollars in profits and abandon products like motion picture print distribution too soon, without having other products to capture the demand.

Ecosystem Troubles

The third part of Kodak’s problem had to do with its ecosystem. Much has been written about the importance of building an ecosystem when a new product or service has to leverage complementary assets. Kodak built a unique and powerful ecosystem to support film-based photography. While the majority of its profits came from manufacturing and selling film, retail partners made large profits from photo finishing. For retailers, it was a wonderful business because it brought customers into their stores multiple times: first to purchase film, then to drop off exposed film for developing and printing, and finally to pick up the prints. Each visit brought ancillary purchases, and photofinishing was one of the top two or three profit generators for many retailers and chain stores. But the end of analog imaging was bringing this golden era to an end.

In hindsight, there were two ecosystem design problems. First, as analog photography declined, there was no reason for retailers to be loyal to Kodak products; many were just as happy to use chemicals and paper from Fuji. Second, Kodak management didn’t fully recognize that the rise of digital imaging would have dire consequences for the future of photo printing.

Organizational Inertia?

Kodak management has been criticized for compromising its digital efforts because it wanted to protect film. But the criticism is overblown. Responding to recommendations from management experts, from the mid-1990s to 2003 the company set up a separate division (which I ran) charged with tackling the digital opportunity. Not constrained by any legacy assets or practices, the new division was able to build a leading market share position in digital cameras — a position that was essentially decimated soon thereafter when smartphones with built-in cameras overtook the market.

A complicated and emotional issue was how to deal with the thousands of people in the legacy businesses that were destined to shrink. Most of the individuals in question knew they didn’t have the right skills for the new businesses; their jobs were to maximize profits from the declining businesses for as long as possible. A few people could make the transition, but the truth is that commoditized digital businesses tend to have lower profit margins and can’t afford to carry a lot of costs — particularly legacy costs.

The organizational challenge was even more pronounced at a senior level. For many managers of legacy businesses, the survival instinct kicked in. Some who had worked at Kodak for decades felt they were entitled to be reassigned to the new businesses, or wished to control sales channels for digital products. But that just fueled internal strife. Kodak ended up merging the consumer digital, professional, and legacy consumer film divisions in 2003. Kodak then tried to make inroads in the inkjet printing business, spending heavily to compete with fortified incumbents such as HP, Canon, and Epson. But the effort failed, and Kodak exited the printer business after it filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy reorganization in 2012.

What Might Kodak Have Done?

With the benefit of hindsight, it’s interesting to ask how Kodak might have been able to achieve a different outcome. One argument is that the company could have tried to compete on capabilities rather than on the markets it was in. This would have meant directing its skills in complex organic chemistry and high-speed coating toward other products involving complex materials — a path followed successfully by Fuji. However, this would have meant walking away from a great consumer franchise. That’s not the logic that managers learn at business schools, and it would have been a hard pill for Kodak leaders to swallow.

For Kodak, it might also have meant holding on to Eastman Chemical Co., a unit it spun off in 1994. After emerging from Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in 2013, Kodak chose to stand its ground in the imaging business. Today, it is a much smaller company that sells products such as commercial printing solutions, while Eastman Chemical, based in Kingsport, Tennessee, has become a major player in industrial chemicals, fibers, and plastics. (Ironically, Eastman Chemical might end up being George Eastman’s most lasting legacy.)

Yet another potential path for Kodak might have been proactively exiting its legacy businesses in a timely way, as IBM Corp. did. From the early 1990s through the 2000s, IBM managed to do this very efficiently, exiting markets that included printer manufacturing, flat panel displays, personal computers, and disk drives. For the company that’s doing the exiting, exiting legacy businesses is an opportunity to restructure and shed a lot of costs. Kodak eventually did this with its consumer film business, which is now owned by Kodak’s U.K. pension plan. But for an organization exiting its traditional business, the real challenge is keeping an innovation pipeline full of new products and services that can replace the old ones. As Kodak has shown, that can be a formidable challenge.

Lessons for Managers

Every situation is different, but the experiences of Kodak suggest some sobering questions for managers in industries undergoing substantial technology-driven change. Among them are:

Is our core technology converging to the point of being replaced by a general-purpose technology platform? If so, the company could lose manufacturing scale and early-mover advantages — such as being far down the legacy manufacturing learning curve.

Is the technology that underpins our business likely to shift to a digital/modular platform that will lower barriers to entry? If so, commoditization pressure will be inevitable, and the company must prepare to live on much lower margins.

Do we have a capital-intensive legacy business? If so, can we develop a strategy for scaling down production volumes that is both capital efficient and keeps production costs from rising excessively? This is key to maximizing cash flow while trying to execute a transition. It will involve using older equipment or repurposing production assets to make alternate products.

How does the balance of power in our ecosystem change as technology shifts impact different parts of the value chain differently? Will the interests of partners cause our company to do things that are contrary to its long-term interests? This requires thinking about how ecosystem partners will manage the transition and adjusting strategy accordingly.

About the Author

Willy Shih is the Robert and Jane Cizik Professor of Management Practice in Business Administration at Harvard Business School. From 1997 to 2003 he was a senior vice president at Eastman Kodak Co. and served as president of the company’s consumer digital business.

More Like This

Add a comment cancel reply.

You must sign in to post a comment. First time here? Sign up for a free account : Comment on articles and get access to many more articles.

Comments (18)

Craig mcgowan, stephen waybright, giovanbattista testolin, karl schubert, arthur weiss, julian koor, victor yodaiken, john krienke, jeffrey hardy, butch cunnings, charles h. green.

More From Forbes

How kodak failed.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

(Update 1-19-2012 — Kodak has filed for bankruptcy protection .)

There are few corporate blunders as staggering as Kodak’s missed opportunities in digital photography, a technology that it invented. This strategic failure was the direct cause of Kodak’s decades-long decline as digital photography destroyed its film-based business model.

A new book by my Devil’s Advocate Group colleague, Vince Barabba , a former Kodak executive, offers insight on the choices that set Kodak on the path to bankruptcy. Barabba’s book, “ The Decision Loom: A Design for Interactive Decision-Making in Organizations ,” also offers sage advice for how other organizations grappling with disruptive technologies might avoid their own Kodak moments.

Steve Sasson, the Kodak engineer who invented the first digital camera in 1975, characterized the initial corporate response to his invention this way:

But it was filmless photography, so management’s reaction was, ‘that’s cute—but don’t tell anyone about it.’ via The New York Times (5/2/2008)

Kodak management’s inability to see digital photography as a disruptive technology, even as its researchers extended the boundaries of the technology, would continue for decades. As late as 2007, a Kodak marketing video felt the need to trumpet that “Kodak is back “ and that Kodak “wasn’t going to play grab ass anymore” with digital.

To understand how Kodak could stay in denial for so long, let me go back to a story that Vince Barabba recounts from 1981, when he was Kodak’s head of market intelligence. Around the time that Sony introduced the first electronic camera, one of Kodak’s largest retailer photo finishers asked him whether they should be concerned about digital photography. With the support of Kodak’s CEO, Barabba conducted a very extensive research effort that looked at the core technologies and likely adoption curves around silver halide film versus digital photography.

The results of the study produced both “bad” and “good” news. The “bad” news was that digital photography had the potential capability to replace Kodak’s established film based business. The “good” news was that it would take some time for that to occur and that Kodak had roughly ten years to prepare for the transition.

Gado via Getty Images

The study’s projections were based on numerous factors, including: the cost of digital photography equipment; the quality of images and prints; and the interoperability of various components, such as cameras, displays, and printers. All pointed to the conclusion that adoption of digital photography would be minimal and non-threatening for a time. History proved the study’s conclusions to be remarkably accurate, both in the short and long term.

The problem is that, during its 10-year window of opportunity, Kodak did little to prepare for the later disruption. In fact, Kodak made exactly the mistake that George Eastman, its founder, avoided twice before, when he gave up a profitable dry-plate business to move to film and when he invested in color film even though it was demonstrably inferior to black and white film (which Kodak dominated).

Barabba left Kodak in 1985 but remained close to its senior management. Thus he got a close look at the fact that, rather than prepare for the time when digital photography would replace film, as Eastman had with prior disruptive technologies, Kodak choose to use digital to improve the quality of film.

This strategy continued even though, in 1986, Kodak’s research labs developed the first mega-pixel camera, one of the milestones that Barabba’s study had forecasted as a tipping point in terms of the viability of standalone digital photography.

The choice to use digital as a prop for the film business culminated in the 1996 introduction of the Advantix Preview film and camera system, which Kodak spent more than $500M to develop and launch. One of the key features of the Advantix system was that it allowed users to preview their shots and indicate how many prints they wanted. The Advantix Preview could do that because it was a digital camera. Yet it still used film and emphasized print because Kodak was in the photo film, chemical and paper business. Advantix flopped. Why buy a digital camera and still pay for film and prints? Kodak wrote off almost the entire cost of development.

As Paul Carroll and I describe in " Billion-Dollar Lessons: What You Can Learn From The Most Inexcusable Business Failures of the Last 25 Years ," Kodak also suffered several other significant, self-inflicted wounds in those pivotal years:

In 1988, Kodak bought Sterling Drug for $5.1B, deciding that it was really a chemical business, with a part of that business being a photography company. Kodak soon learned that chemically treated photo paper isn’t really all that similar to hormonal agents and cardiovascular drugs, and it sold Sterling in pieces, for about half of the original purchase price.

In 1989, the Kodak board of directors had a chance to take make a course change when Colby Chandler, the CEO, retired. The choices came down to Phil Samper and Kay R. Whitmore. Whitmore represented the traditional film business, where he had moved up the rank for three decades. Samper had a deep appreciation for digital technology. The board chose Whitmore. As the New York Times reported at the time,

Mr. Whitmore said he would make sure Kodak stayed closer to its core businesses in film and photographic chemicals. via The New York Times (12/9/1989)

Samper resigned and would demonstrate his grasp of the digital world in later roles as president of Sun Microsystems and then CEO of Cray Research. Whitmore lasted a little more than three years, before the board fired him in 1993.

For more than another decade, a series of new Kodak CEOs would bemoan his predecessor’s failure to transform the organization to digital, declare his own intention to do so, and proceed to fail at the transition, as well. George Fisher, who was lured from his position as CEO of Motorola to succeed Whitmore in 1993, captured the core issue when he told the New York Times that Kodak

regarded digital photography as the enemy, an evil juggernaut that would kill the chemical-based film and paper business that fueled Kodak’s sales and profits for decades. via The New York Times (12/25/1999)

Fisher oversaw the flop of Advantix and was gone by 1999. As the 2007 Kodak video acknowledges, the story did not change for another decade. Kodak now has a market value of $140m and teeters on bankruptcy. Its prospects seem reduced to suing Apple and others for infringing on patents that it was never able to turn into winning products.

Addressing strategic decision-making quandaries such as those faced by Kodak is one of the prime questions addressed in Vince Barabba’s book, “ The Decision Loom .” Kodak management not only presided over the creation technological breakthroughs but was also presented with an accurate market assessment about the risks and opportunities of such capabilities. Yet Kodak failed in making the right strategic choices.

This isn’t an academic question for Vince Barabba but rather the culmination of his life’s work. He has spent much of his career delivering market intelligence to senior management. In addition to his experiences at Kodak, his career includes being director of the U.S. Census Bureau (twice), head of market research at Xerox , head of strategy at General Motors (during some of its best recent years), and inclusion in the market research hall of fame.

Vince Barabba

“ The Decision Loom ” explores how to ensure that management uses market intelligence properly. The book encapsulates Barabba’s prescription of how senior management might turn all the data, information and knowledge that market researchers deliver to them into the wisdom to make the right decisions. It is a prescription well worth considering.

Barabba argues that four interrelated capabilities are necessary to enable effective enterprise-wide decision-making—none of which were particularly well-represented during pivotal decisions at Kodak:

1. Having an enterprise mindset that is open to change. Unless those at the top are sufficiently open and willing to consider all options, the decision-making process soon gets distorted. Unlike its founder, George Eastman, who twice adopted disruptive photographic technology, Kodak’s management in the 80’s and 90’s were unwilling to consider digital as a replacement for film. This limited them to a fundamentally flawed path.

2. Thinking and acting holistically. Separating out and then optimizing different functions usually reduces the effectiveness of the whole. In Kodak’s case, management did a reasonable job of understanding how the parts of the enterprise (including its photo finishing partners) interacted within the framework of the existing technology. There was, however, little appreciation for the effort being conducted in the Kodak Research Labs with digital technology.

3. Being able to adapt the business design to changing conditions. Barabba offers three different business designs along a mechanistic to organismic continuum—make-and-sell, sense-and-respond and anticipate-and-lead. The right design depends on the predictability of the market. Kodak’s unwillingness to change its large and highly efficient ability to make-and-sell film in the face of developing digital technologies lost it the chance to adopt an anticipate-and-lead design that could have secured the it a leading position in digital image processing.

4. Making decisions interactively using a variety of methods . This refers to the ability to incorporate a range of sophisticated decision supporttools when tackling complex business problems. Kodak had a very effect decision support process in place but failed to use that information effectively.

While “ The Decision Loom ” goes a long way to explaining Kodak’s slow reaction to digital photography, its real value is as a guidepost for today’s managers dealing with ever-more disruptive changes. Given that there are few industries not grappling with disruptive change, it is a valuable book for any senior (or aspiring) manager to read.

- Editorial Standards

- Reprints & Permissions

MBA Knowledge Base

Business • Management • Technology

Home » Management Case Studies » Case Study on Business Strategies: Kodak’s Transition to Digital

Case Study on Business Strategies: Kodak’s Transition to Digital

Kodak is one of the oldest companies on the photography market, established more than 100 years ago. This was the iconic, American organization, always on the position of the leader. Its cameras and films have become know all over the world for its innovations. Kodak’s strength was it brand — one of the most recognizable and resources, that enabled creating new technologies. Since the formation of Kodak, the company has remained the world’s leading film provider with virtually no competitors. That is until the arrival of Fuji Photo Film, which now surpasses Kodak in earnings per share and is viewed as the industries number two. It is evident that there has been a significant shift from the use of traditional film cameras to a market fully fledged and saturated with modern and updated digital cameras and digital photographic tools.

However over the time, the situation started to change for Kodak, as it has underestimated the changes on the market. There has been a significant shift from the use of traditional film cameras to a market fully fledged and saturated with modern and updated digital cameras and digital photographic tools. The age of digital technologies were emerging. The core business of Kodak- the film business, started to decline and some areas of the business started to be less profitable and filled with many competitors, especially cheap ones from Asia. Also, the prices of the digital cameras were falling.

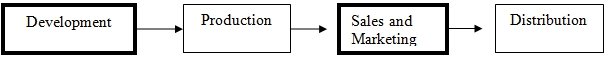

Eastman Kodak is divided into three major areas of production.

- Kodak’s Digital and Film Imaging Systems section produces digital and traditional film cameras for consumers, professional photographers, and the entertainment industry.

- Health Imaging caters to the health care market by creating health imaging products such as medical films, chemicals, and processing equipment.

- The Commercial Imaging group produces aerial, industrial, graphic, and micrographic films, inkjet printers, scanners, and digital printing equipment to target commercial and industrial printing, banking, and insurance markets.

Issues and Challenges

The main issue behind this case is the problems faced by the Eastman Kodak Company in the process of changing to Digital technology in printing. It failed to establish market share and market leadership in the Digital sector. It is threatened with either immediate or rapid diversification in technology. Kodak has been extremely successful over the last century in film sales and film development. Now the time has come for the Eastman Kodak to respond to the challenges of digital cameras and also contemplate other issues as follows:

- Will the company’s current strengths and capabilities to make Kodak as ‘The Picture Company”?

- How serious are the weakness and competitive deficiencies?

- Does the company have attractive market opportunities that are well suited with Kodak’s resources? Does it have the internal resources to continue spending money investing in new technology?

- What type of strategy should it use to enter the digital camera business and how will Kodak leverage its strategic resources?

- Should it continue to research and produce digital camera technology alone, or look for partners?

- How will it cope with their existing and new competitors and how will it build a strategic advantage over other companies? Can Kodak once again dominate the world market?

What went wrong at Kodak?

Kodak started facing difficulties in 1984, when the Japanese firm Fuji Photo Film Co. invaded on Kodak’s market share as customers switched to their products after launching a 400-speed color film that was 20% cheaper than Kodak’s. Secondly, during 1980s the company failed to recognize the change in the environment and instead followed and sticked to a business model that was no longer valid for the post-digital age. After the management realized the change and react accordingly but it was too late.

Kodak’s strength

Kodak’s strength can take several forms as follows:

- Valuable intangible assets : Kodak’s strengths were its brand equity and distribution presence. After almost a century of global leadership in the photographic industry, Kodak possessed brand recognition and worldwide distribution. Kodak could bring new products to consumers’ attention and to support these products with one of the world’s best known and most widely respected brand names as a huge advantage in the market where technological change created uncertainty for consumers. Kodak’s brand reputation was supported by its massive. , worldwide distribution presence — primarily through retail photography stores, film processors, and professional photographers.

- Competitive Capabilities : Prior to 1990s Kodak had invested huge in R&D. Moreover, its century of innovation and development of photographic images gave Kodak tremendous depth of understanding of recording and processing images. Central to Kodak’s imaging capability was its color management capability. In the digitizing color and transferring digital images to paper, Kodak possessed a powerful set of complementary technologies in sensing, color management and thermal printing.

- Market advantage: Through its wider distribution network, it has been able to maintain a huge market coverage and accessibility. It had worldwide distribution presence — primarily through retail photography stores, film processors, and professional photographers.

Company’s competence and Competitive capabilities

- Competency : Eastman Kodak has been Leveraging competencies in film and paper media, color management. It has been known for the best quality films and cameras worldwide. Its journey of more than 100 years has helped to gain the experience and excel in its Endeavour. The organizational changes like decentralization and accountability that George Fisher made helped increase speed of manufacturing and product development .i.e short product development cycles. Secondly, a strength could be also considered Kodak’s favorable corporate image (and implicitly a significant brand equity) that results from the values which are said to lead the staff’s behaviors (“respect for the dignity of the individual, integrity, trust, credibility, continuous improvement and personal renewal, recognition and celebration”), a transparent management which allows shareholders to have a realistic and up-to-date image of the operations performed, strong Human Resources policies and commitment to the community.

- Core Competency : Eastman Kodak was a highly integrated company that did its own R&D and manufactured its own parts. Changing global markets and cost pressures in the 1980s and 1990s threatened the way of doing business. So the knowledge, company’s intellectual capital are also affected and repercussion is proficiency in its core competency started diminish. George Fisher, CEO in 1993, refocused the company on core competencies and joined the trend of outsourcing with close relationships to suppliers and announced a new explicit social contract as part of the restructuring effort. By 1997, the company could not grow out of its competitiveness problems like major price competition from its biggest international competitor, Fuji, which was engaged in a major price-cutting campaign aimed at increasing its market share internationally and particularly in U.S. markets. In response, Kodak made more significant changes designed to reduce its costs and to recapture market share in the company’s core products. But all these attempts only lead to decrease market share and declining profit.

- Distinctive Competency : Firstly, the brand image of the company that has been built since century is the distinctive competency for Kodak. Before the digital age, its distinctive competencies were film and Cameras and its sister concern for its chemical technology.

Strategies of Eastman Kodak

- Vertical integration combined with continuous innovation and product development. Speed is also required cutting cycle times in manufacturing and product development.

- To systematize and accelerate product development and improve product-launch, quality, Kodak introduced a new product development methodology called “Manufacturing Assurance Process”(MAP).

- Joint venture with HP, Microsoft to introduce new products that required in the market. Collaborate with expert to enhance the competency.

- Digital strategy was to create greater coherence among Kodak’s multiple digital projects.

- Previously they had diversification strategy but later Fisher focus in Imaging business.

Source: Scribd.com

Related posts:

- Case Study: McDonald’s Business Strategies in India

- Case Study on Apple’s Business Strategies

- Case Study: Walt Disney’s Business Strategies

- Case Study on Business Strategies: The Downfall of Sun Microsystems

- Case Study of Qantas Airlines: Business Model and Strategies

- Case Study on Business Strategies: Failure Stories of Gateway and Alcatel

- Case Study: Airbnb’s Growth Strategy Using Digital Marketing

- Case Study: L’Oreal Marketing Strategies in India

- Case Study of Toyota: International Entry Strategies

- Case Study of McDonalds: Advertising and Promotion Strategies

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Brought to you by:

The Reinvention of Kodak

By: Ryan L. Raffaelli, Christine Snively

The Eastman Kodak Company (Kodak) was a name familiar to most Americans. The company had dominated the film and photography industry through most of the 20th Century and was known for making…

- Length: 23 page(s)

- Publication Date: Nov 30, 2018

- Discipline: Organizational Behavior

- Product #: 419012-PDF-ENG

What's included:

- Teaching Note

- Educator Copy

- Supplements

$4.95 per student

degree granting course

$8.95 per student

non-degree granting course

Get access to this material, plus much more with a free Educator Account:

- Access to world-famous HBS cases

- Up to 60% off materials for your students

- Resources for teaching online

- Tips and reviews from other Educators

Already registered? Sign in

- Student Registration

- Non-Academic Registration

- Included Materials

Instructors should consider the timing of making the video available to students, as it may reveal key case details.

The Eastman Kodak Company (Kodak) was a name familiar to most Americans. The company had dominated the film and photography industry through most of the 20th Century and was known for making affordable cameras (and the "Kodak Moment") and supplying the movie industry with film. At its peak in 1997, Kodak had a market value of $30 billion. Despite inventing the first digital camera, Kodak stumbled to capitalize on the new technology and by 2011 the company was in Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. In September 2013, Kodak emerged from bankruptcy as a smaller business-to-business (B2B) digital imaging company. The following March, Jeff Clarke took over as Kodak's new CEO. The company continued to produce and sell film to moviemakers, but Clarke, who needed to reinvent Kodak, wondered if keeping that business line made sense. To some inside the company, film was a "sacred cow" and fundamental to Kodak's identity. In January 2016, Clarke and his executive team traveled to Las Vegas, Nevada, for the annual Consumer Electronics Show (CES) where the company unveiled a prototype of its new Super 8 camera-an analog motion picture camera initially launched in 1965 to shoot home movies-with updated features. Over the course of the four-day event, media and other industry players had overwhelmed the Kodak booth, excited to catch a glimpse of the camera, asking when they could expect to see the Super 8 on shelves. While the business-to-business (B2B) side of the company appeared to be growing, the new Super 8 reflected the culture and identity of a firm originally rooted in film and consumer products. Sentiment aside, Clarke needed to decide if the new Super 8 fit into the company's overall strategy and whether Kodak was focused on the right markets for growth. What was the optimal path to reinvention?

Nov 30, 2018 (Revised: Aug 24, 2020)

Discipline:

Organizational Behavior

Harvard Business School

419012-PDF-ENG

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience, including personalizing content. Learn More . By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Kodak and the Brutal Difficulty of Transformation

- Scott D. Anthony

2012 has not gotten off to a great start for Eastman Kodak. Three of the company’s directors quit near the end of last year, and word recently emerged that the company was on the brink of filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. The easy narrative is that Kodak is a classic case of a company […]

2012 has not gotten off to a great start for Eastman Kodak. Three of the company’s directors quit near the end of last year, and word recently emerged that the company was on the brink of filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection.

- Scott D. Anthony is a clinical professor at Dartmouth College’s Tuck School of Business, a senior partner at Innosight , and the lead author of Eat, Sleep, Innovate (2020) and Dual Transformation (2017). ScottDAnthony

Partner Center

Why Did Kodak Fail? | Kodak Bankruptcy Case Study

Yash Taneja

Kodak, as we know it today, was founded in the year 1888 by George Eastman as ‘The Eastman Kodak Company’ . It was the most famous name in the world of photography and videography in the 20th century. Kodak brought about a revolution in the photography and videography industries. At the time when only huge companies could access the cameras used for recording movies, Kodak enabled the availability of cameras to every household by producing equipment that was portable and affordable.

Kodak was the most dominant company in its field for almost the entire 20th century, but a series of wrong decisions killed its success. The company declared itself bankrupt in 2012. Why did Kodak, the king of photography and videography, go bankrupt? What was the reason behind Kodak's failure? Why did Kodak fail despite being the biggest name of its time? This case study answers the same.

Why Did Kodak Fail? Biggest Reason Of Kodak's Failure - Fights against Fuji Films Kodak's Bankruptcy Protection Ressurection of Kodak: Kodak in the mobile industry?

Why Did Kodak Fail?

Kodak, for many years, enjoyed unmatched success all over the world. By 1968, it had captured about 80% of the global market share in the field of photography.

Kodak adopted the 'razor and blades' business plan . The idea behind the razor-blade business plan is to first sell the razors with a small margin of profit. After buying the razor, the customers will have to purchase the consumables (the razor blades in this case) again and again; hence, sell the blades at a high-profit margin. Kodak's plan was to sell cameras at affordable prices with only a small margin for profit and then sell the consumables such as films, printing sheets, and other accessories at a high-profit margin .

Using this business model, Kodak was able to generate massive revenues and turned into a money-making machine.

As technology progressed, the use of films and printing sheets gradually came to a halt. This was due to the invention of digital cameras in 1975. However, Kodak dismissed the capabilities of the digital camera and refused to do something about it. Did you know that the inventor of the digital camera, Steven Sasson, was an electrical engineer at Kodak when he developed the technology? When Steven told the bosses at Kodak about his invention, their response was, “That’s cute, but don’t tell anyone about it. That's how you shoot yourself in the foot!"

Kodak ignored digital cameras because the business of films and paper was very profitable at that time and if these items were no longer required for photography, Kodak would be subjected to huge losses and end up closing down the factories which manufactured these items.

The idea was then implemented on a large scale by a Japanese company by the name of ‘Fuji Films’. And soon enough, many other companies started the production and sales of digital cameras, leaving Kodak way behind in the race.

This was Kodak's first mistake. The ignorance of new technology and not adapting to the changing market dynamics initiated Kodak's downfall.

List of Courses Curated By Top Marketing Professionals in the Industry

These are the courses curated by Top Marketing Professionals in the Industry who have spent 100+ Hours reviewing the Courses available in the market. These courses will help you to get a job or upgrade your skills.

Biggest Cause Of Kodak's Failure

After the digital camera became popular, Kodak spent almost 10 years arguing with Fuji Films , its biggest competitor, that the process of viewing an image captured by the digital camera was a typical process and people loved the touch and feel of a printed image. Kodak believed that the citizens of the United States of America would always choose it over Fuji Films, a foreign company.

Fuji Films and many other companies focused on gaining a foothold in the photography & videography segment rather than engaging in a verbal spat with Kodak. And once again, Kodak wasted time promoting the use of film cameras instead of emulating its competitors. It completely ignored the feedback from the media and the market . Kodak tried to convince people that film cameras were better than digital cameras and lost 10 valuable years in the process.

Kodak also lost the external funding it had during that time. People also realized that digital photography was way ahead of traditional film photography. It was cheaper than film photography and the image quality was better.

Around that time, a magazine stated that Kodak was being left behind because it was turning a blind spot to new technology. The marketing team at Kodak tried to convince the managers about the change needed in the company's core principles to achieve success. But Kodak's management committee continued to stick with its outdated idea of relying on film cameras and claimed the reporter who said the statement in the magazine did not have the knowledge to back his proposition.

Kodak failed to realize that its strategy which was effective at one point was now depriving it of success. Rapidly changing technology and market needs negated the strategy. Kodak invested its funds in acquiring many small companies, depleting the money it could have used to promote the sales of digital cameras.

When Kodak finally understood and started the sales and the production of digital cameras, it was too late. Many big companies had already established themselves in the market by then and Kodak couldn't keep pace with the big shots.

In the year 2004, Kodak finally announced it would stop the sales of traditional film cameras. This decision made around 15,000 employees (about one-fifth of the company’s workforce at that time) redundant. Before the start of the year 2011, Kodak lost its place on the S&P 500 index which lists the 500 largest companies in the United States on the basis of stock performance. In September 2011, the stock prices of Kodak hit an all-time low of $0.54 per share. The shares lost more than 50% of their value throughout that year.

Kodak's Bankruptcy Protection

By January 2012, Kodak had used up all of its resources and cash reserves. On the 19th of January in 2012, Kodak filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection which resulted in the reorganization of the company. Kodak was provided with $950 million on an 18-month credit facility by the CITI group.

The credit enabled Kodak to continue functioning. To generate more revenue, some sections of Kodak were sold to other companies. Along with this, Kodak decided to stop the production and sales of digital cameras and stepped out of the world of digital photography. It shifted to the sale of camera accessories and the printing of photos.

Kodak had to sell many of its patents, including its digital imaging patents, which amounted to more than $500 million in bankruptcy protection. In September 2013, Kodak announced it had emerged from Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection.

Ressurection of Kodak: Kodak in the mobile industry?

Celebrated camera accessory manufacturers of yesteryear, Kodak, is looking to join Chinese smartphone manufacturing giant Oppo for an upcoming flagship smartphone. This new smartphone is rumored to have 50MP dual cameras, where the cameras of the device will be modeled upon the old classic camera designs of the Kodak models.

The all-new flagship model of Oppo is designed to be a tribute to the classic Kodak camera design. The camera of this Oppo model will allegedly use the Sony IMX766 50MP sensor. Furthermore, the phone will also embed a large sensor in its ultrawide camera as well along with a 13MP telephoto lens and a 3MP microscope camera.

No other information on this matter is currently available as of September 13, 2021.

The collaborations between Android OEMs and camera makers are not something new. Yes, numerous other companies have already come together with other camera manufacturing companies like Nokia, which joined hands with German optics company Carl Zeiss earlier in 2007 to bring in the camera phone Nokia N95. This can be concluded as the first of such collaborations that the smartphone industry has seen. Numerous other collaborations happened eventually, which resulted in outstanding results. OnePlus' partnership with Hasselblad, Huawei pairing up with Leica and the recent news of Samsung's associating with Olympus are some of the significant collaborations to be mentioned.

Kodak had earlier made a leap into the smart TV industry and is ushering in success through this new move. Kodak TV India has already commissioned a plant in Hapur, Uttar Pradesh in August 2020, designed to manufacture affordable Android smart TVs for India. Furthermore, the renowned photography company is looking to invest more than Rs 500 crores during the next 3 years for making a fully automated TV manufacturing plant possible in Hapur. The company committed to this plan as part of its ‘Make in India’ initiative and will leverage its Android certification. Kodak's announcement, as it seemed, was further recharged with the Aatmanirbhar Bharat campaign launched by PM Narendra Modi in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic in 2020.

The TV industry of India imports most of its raw materials and exhibits a value addition of only about 10-12%. However, with the investment that Kodak has promised the company has aimed to increase the value-added to around 50-60%. The Hapur R&D facility will foster the manufacturing of technology-driven products and introduce numerous other lines of manufacturing aligned with the "Make in India" belief.

Super Plastronics Pvt Ltd, a Noida-based company has obtained the license from Kodak Smart TVs to produce and sell their products in India in partnership with the New-York based company and has already launched a range of smart TVs already, as of September 2021 including:

- Kodak 40FHDX7XPRO 40-inch Full HD Smart LED TV

- Kodak 43FHDX7XPRO 43-inch Full HD Smart LED TV

- Kodak 42FHDX7XPRO 42-inch Full HD Smart LED TV

- Kodak 32HDXSMART 32-inch HD ready Smart LED TV

and more. Besides, Kodak HD LED TVs were also up for sale at the lowest prices for 2020, in partnership with Flipkart and Amazon for The Big Billion Days Sale and the Great Indian Sale respectively. This sale, which took place between 16th and 21st October 2020, also included the all-new Android 7XPRO series, which starts at Rs 10999 only and is currently dubbed as the most affordable android tv in India.

Want to Work in Top Gobal & Indian Startups or Looking For Remote/Web3 Jobs - Join angel.co

Angel.co is the best Job Searching Platform to find a Job in Your Preferred domain like tech, marketing, HR etc.

What happened to Kodak?

Kodak was ousted from the market of camera and photography due to numerous missteps. Here are some insights into the same:

- The ignorance of new technology and not adapting to changing market needs initiated Kodak's downfall

- Kodak invested its funds in acquiring many small companies, depleting the money it could have used to promote the sales of digital cameras.

- Kodak wasted time promoting the use of film cameras instead of emulating its competitors. It completely ignored the feedback from the media and the market

- When Kodak finally understood and started the sales and the production of digital cameras, it was too late. Many big companies had already established themselves in the market by then and Kodak couldn't keep pace with the big shots

- In September 2011, the stock prices of Kodak hit an all-time low of $0.54 per share

- Kodak declared bankruptcy in 2012

Why did Kodak fail and what can you learn from its demise?

Kodak failed to understand that its strategy of banking on traditional film cameras (which was effective at one point) was now depriving the company of success. Rapidly changing technology and evolving market needs made the strategy obsolete.

Is Kodak still in Business?

Kodak declared itself bankrupt in 2012. Kodak's bankruptcy resulted in the formation of the Kodak Alaris company, a British organization that part-owns the Kodak brand along with the American Eastman Kodak Company.

When did Kodak go out of business?

Kodak faced its demise in 2012.

Is Kodak a good camera?

Kodak's cameras and accessories were of premium quality and the first of the choices professional photographers and others. The company was a winner in the analogue era of photography. However, the company dived down to hit the rock-bottom level.

What does Kodak do now?

Currently, Kodak provides packaging, functional printing, graphic communications, and professional services for businesses around the world. Better known for making cameras, Kodak moved into drug making and has secured a $765m (£592m) loan from the US government in 2020.

Why was Kodak so successful?

Kodak adopted the 'razor and blades' business plan. The idea here was to first sell the razors with a small margin of profit. After buying the razor, the customers will have to purchase the consumables (the razor blades in this case) again and again; hence, sell the blades at a high-profit margin. Kodak's plan was to sell cameras at affordable prices with only a small margin for profit and then sell the consumables such as films, printing sheets, and other accessories at a high-profit margin.

Must have tools for startups - Recommended by StartupTalky

- Manage your business smoothly- Google Workspace

Oleg Jelesko: Global Investment Success With Da Vinci Capital Management

Oleg Jelesko is recognized for his extensive experience and reputation in the business world, notably for his impact within a network of investors and financial experts. He founded an investment company, Da Vinci Capital Management, that has made a significant mark in the market, highlighted by its diverse portfolio of

Top Sponsors of the ICC T20 World Cup 2024

Lots of businesses are putting their money into the Twenty20 World Cup 2024, the biggest event in international cricket that is currently underway. With over 200 million viewers for the most recent tournament in 2022, the Cricket World Cup is second only to the FIFA World Cup in terms of

7 Must-Have Features In An All-In-One HR Software For Startups

Juggling the demands of running a startup can feel like a three-ring circus. From developing a groundbreaking product to building a dream team, founders wear many hats and often work tirelessly to keep all the plates spinning. However, one area that can easily slip through the cracks is human resources

Hisham Mundol, Chief Advisor at Environmental Defense Fund, India, Shares Insights on the Country's Green Future

In the spirit of World Environment Day, StartupTalky presents an exclusive interview with Hisham Mundol, Chief Advisor at Environmental Defense Fund, India. Explore his expertise as he discusses India's sustainable growth, EDF's impactful initiatives in climate action, and the crucial role of businesses and individuals in protecting our environment. Gain

- Sudipta Kashyap

- Sep 15, 2021

- 14 min read

Failure of Kodak: An investigation with the application of the paradox of strategy

An age ago, the phrase, "Kodak moment," implied something that was worth saving and enjoying. Today, however, the term progressively fills in to describe a corporate disaster that cautions the chiefs of various companies of the need to stand up and react when problematic improvements infringe on their market. Even though Kodak is sadly neglected from the failure it encountered, it has taught various other businesses some major lessons.

The correct lessons from Kodak are unpretentious. Organizations frequently see the troublesome powers influencing their industry. They as often as possible redirect adequate assets to take an interest in developing the business sectors. Their disappointment is typically powerlessness to really grasp the new plans of action as the troublesome switch opens. Kodak made a computerized camera, put resources into the innovation, and even comprehended that the photographs would be shared on the web. Where they fizzled, was in understanding that online photograph sharing was the new business, not simply an approach to extend the printing business.

Therefore, I use this common occurrence when companies fail to understand the future of the market and continue to stick to their main line of business as an example of the paradox of strategy as explained by Michael E. Raynor in his book, “The strategy paradox”

Keywords : strategy paradox, technological paradigm, innovation

Introduction

Kodak was the most well-known name in the realm of photography and videography in the twentieth century. The company achieved an insurgency in the photography and videography businesses with annual revenue of 11,395 billion dollars up to 2005. In any case, the achievement of the organization continuously started to transform into disappointment because of its slip-ups in its market prediction. The ruin of Kodak began around the 90s and the organization proclaimed itself bankrupt in 2012.

Here is a confounding reality: the best firms frequently share more for all intents and purposes with failed associations than with those that have overseen simply to endure, which explains that more lessons are to be learnt from failed businesses rather than the flourishing works. Truth be told, the very qualities that we have come to distinguish as determinants of accomplishment are additionally the elements of disappointment. Thus incidentally, something contrary to progress isn't a disappointment, it is mediocrity.

This paper takes the model of a case study analysis where we critically analyze the performance of Kodak from its conception to its present-day scenario. The story of Kodak serves as a perfect example for the paradox of strategy and will reiterate this point in the last section of the paper after an in-depth inquiry into the structure and the management of Kodak. This paper will present the findings which will be used to establish the connection between the paradox of strategy and Kodak.

Problem statement/Research problem

The central problem of my research is to explain the concept of paradox of strategy, its implications with relation to the case study of Kodak. It aims to give an overall analysis as to strategies with the best chance of accomplishment, additionally have the best chance of disappointment. Settling this paradox requires another perspective about procedure and vulnerability which will be viewed through the story of Kodak and a timeline of its decisions and decline.

Literature Review

The Strategy Paradox, a book by Michael E. Raynor : The title and focal point of the book sets up an omnipresent, however, the little-got tradeoff between a decision to be taken based on the present or future market perspectives. The tradeoffs are based on explicit convictions about an eccentric future, yet current key methodologies using the past performance of markets power pioneers focus on an unyielding methodology paying little heed to how the future may unfurl. It is this obligation to the vulnerability that is the reason for "the methodology oddity.” which means that a particular methodology may or may not work and can be determined only by the future.

Barriers of change: The Real Reason behind the Kodak Downfall by John Kotter : The Kodak issue, by all accounts, as indicated by the article, is that it didn't move into the computerized world sufficiently quickly. Recent articles borrow a touch more and find that there were individuals who saw the issue coming and individuals covered in the association however the firm didn't act when it ought to have.

How Underdeveloped Decision Making and Poor Leadership Choices Led Kodak into Bankruptcy : While it is impossible to fully comprehend the mechanics of Kodak’s failure, poor decision making, and leadership appear to have played prominent roles in the company’s decline and bankruptcy. With these lenses, Kodak’s downfall is analyzed with attention to Kodak’s leaders and the underdeveloped decision-making routines they followed.

Research Gap

I believe that my study shall help those companies looking forward to taking risks, especially during the unprecedented and uncontrollable times of Covid-19. It speaks about the danger of undermining such risks in the enthusiasm of making a daring decision by rewinding the story of Kodak.

Research Objectives

To examine the decisions of Kodak after establishing themselves as a well-known name in the realm of photography and videography, and the effects of the same on their market share over the years.

To analyze the motives behind these decisions and how Kodak took risky decisions in a few situations that ultimately resulted in their breakdown.

To prove the paradox of strategy as a reason for their downfall and justify the same with different models and frameworks.

Research Design and Methodology

My paper is primarily dependent on qualitative analysis and therefore uses secondary data to justify the hypothesis. The data used in the paper is spread across different time periods. The statistics shall cover the annual revenue of the company from 2005-2019, the worldwide market share of photography companies from January 2010 to July 2020, the consumer satisfaction, quarterly net income and popularity of the brand in the photography industry. Due to the use of secondary data and variables, the study adopts descriptive statistics and majorly includes variables such as the annual revenue, quarterly net income, global market share and consumer satisfaction, to name a few. All these variables are dependent on the decisions taken by the enterprise and other factors prevailing in the market.

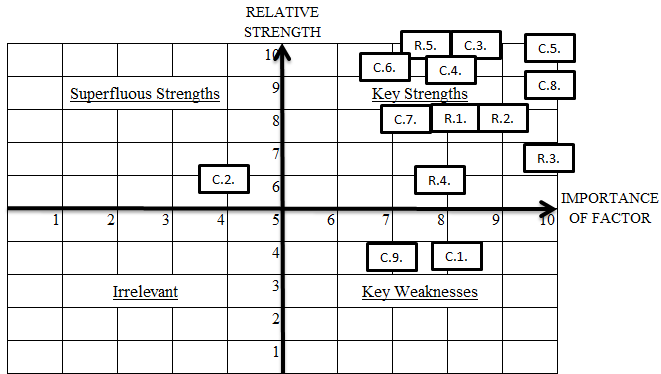

In the qualitative study I have chosen models such as SWOT Analysis, McKinsey’s 7S Framework, strategic management cycle and value Discipline Model to analyze the business history of Kodak and why certain decisions were taken and why a few of them were ignored.

Theoretical background to the paradox of strategy

Even though in most circumstances it is impossible for us to overcome the paradox of strategy, according to experts a flexible business plan will do the work. When the leaders of a company design a strategy with goal setting, they may have been proved wrong through technological paradigm shifts or environmental and legal factors. Over a course of time, their goals and strategies seem either too old or irrelevant in the current market space but in most cases, such a realization comes late and ultimately leads to its failure. Even though in an actual sense the strategy taken by the company would have been perfect years back they will face a backlash from current circumstances.

History of Kodak

Kodak can be characterized with the story of huge success during the 1970s but consequently a story of failure by 2012. The company was in bankruptcy during the year 2012 and it is important to understand how this company that ruled the photography market for years, suddenly saw a backlash.

George Eastman and Henry Strong are the founders of this massive franchise. The name “Kodak'' was coined by George Eastman in the 1800s and he played an important role in the company, while Henry Strong was mostly an investor. Photography before the 1800s majorly involved huge and heavy cameras that took hours of travel, shooting and printing. Kodak was reputed to have revolutionized the process of photography in the world. They introduced small portable cameras and worked with the tagline “Press the button and we do the rest”. These cameras were made available to the public and were extremely handy. Kodak soon introduced films for processing the photos. However, there were huge complaints as these cameras required particularly Kodak films for the processing which saw a huge fall in the prices of their films. In 2009 the production of films ultimately stopped. In 1976, Kodak was controlling 85% of the camera industry and 90% of the filmmaking industry.

They had a major fall in 2005 when digital cameras started ruling the market. Most people believe that Kodak ignored the camera market in 1990 however, that is not what happened. Kodak was the first to invent, as well receive a patent for digital cameras. Surprisingly, where they saw a downfall, was their plan to use the digital camera production as a side business and underestimating its role in the market. They wanted something to be so true that they decided the digital cameras would do them no good and such an attitude was caused due to their overestimated experience.

Soon by 2005, they only held 7.5% of the global market share for cameras and were stepping into the production of printers where they faced competition from HP and other established companies. Even though Kodak continues to exist in the present day, calling themselves a printer company, they have come a long way from bankruptcy. In the present day, considering the emergence of social media, it’s doubtful that they would have sustained in the market.

Quantitative

Annual Revenue: 2005-2019: 2005 is termed as the year when Kodak saw its nightmare. It was the year when digital cameras were introduced and since then it has been a journey off the track. As explanatory as the graph is, the annual revenue of Kodak drastically decreased from 2005-2009. 2010 was the period when various photo-sharing platforms were introduced further deepening the losses .

Retrieved from: Eastman Kodak revenue 2005-2019 | Statista

2) Global market share: This picture speaks a lot about the global market share that Kodak had and its decline in just 10 years from 11,000 to 1,200 billion dollars. The reasons add up to many including the failure to capture the digital camera market, no attempt made to join the e-sales and services and swift competition from mobile phones and photo-sharing platforms.

Retrieved from: Cutting and pasting about Kodak’s demise – keeping simple (yodaiken.com)

Kodak Stock market prices: 2006-2011: A similar story was followed in Kodak’s stock market values. The company managed to keep hold of high prices for its stocks with loyal consumers and blooming market expectations. Over the years, they had set records and made their tagline “Kodak Moments” a household slang. With the career of the company at its peak, investors saw zero harm in investing and in fact had high expectations for its returns. However, as Kodak failed to capture the digital camera market or enter e-business and services, traditional marketing and product portfolio demonstrated nothing but losses. In the period of 10 years between 2005-2015, Kodak lost almost all its hold on the market and the earnings per share dropped dead. Investors no longer trusted the company’s marketing strategies and business decisions and soon were convinced of the company’s bankruptcy, especially due to the introduction of smartphone cameras and online photo-sharing apps. Surprisingly, they were not wrong.

Retrieved from: KODAK stock price (typepad.com)

Qualitative

Value discipline model

A value discipline model assists the organization with breaking down their qualities and shortcomings and investigating the chances to build up a compelling arrangement for the market. This section talks about the essential investigation of Eastman Kodak Company to foster a strategic plan.

Product Leadership : This category under the value discipline model explains the variety of products that a company can bring to the market through research and development. The Eastman Kodak company did not lack in research or development and were in fact the first one to introduce digital cameras in the market. However, the real reason behind the downfall was the priority of marketing for a particular product that is the Kodak films. Along with an innovative product, there should always be good marketing and advertising.

Consumer Intimacy: Consumer Intimacy is not just the skill to understand the needs and wants of the consumer, but to go beyond. Kodak, in this sphere, was a pioneer, and had shown exceptional results. They came up with extremely creative and relatable taglines like “Kodak Moments”. They reduced the prices of the films to satisfy the demands of the consumer, which later popularly came to be known as the ‘Kodak moments.’ Every picture of memory in the 1970s reminded everyone about Kodak and its films.

Operational efficiency : Remaining in the market for a very long period, Kodak had no trouble in establishing operational efficiency through its remarkable experience and leadership. They delivered fine products at reasonable prices making cameras available for the public which was not a common scenario in the past.

SWOT analysis

SWOT Analysis helps analyse the strengths and weaknesses along with the various opportunities and threats that a company faces or has been facing to understand what brackets certain decisions shall come under.

Brand : Kodak as a brand has and always been a name very familiar to our ears even though it has been a long time since its presence has diminished. Kodak had established itself as a brand even though it slowly lost hold of the market.

Product portfolio : Kodak has expanded their product portfolio moving from cameras films to digital cameras as well, that were recognized through the brand name.

Technology : Kodak has not stood back from technology, considering they were the first ones to invent digital cameras.

Socially and environmentally responsible : They were socially responsible and contributed to the reduction in the emission of greenhouse gases.

Weaknesses:

E-commerce industry : Kodak failed to switch to the e-commerce industry which backlashed and reduced its position in the market. As various other companies worked on switching to the industry, Kodak took a step back.

Wrong Decisions : The company made a few wrong decisions like considering their hesitation in making the digital camera an important part of their supply chain.

Opportunities

Digital Media : The coming up of various digital media platforms has been a threat to Kodak such as Instagram and Facebook. Kodak could see a better business future with their industry in the digital media as well.

Change in the main product : Kodak can change their main business line and make amends to introduce modern-day technology and products for better market outreach across the world, both in developed and developing countries.

Competition : The major reason for the Kodak downfall was the competition that took over the market by a swirl through modern-day technology and equipment such as Instagram and Facebook, unlike Kodak that stuck to its old traditional means

Substitute products : A mobile phone has replaced traditional cameras in most households and reduced the consumer base dependent on cameras. In years to come, the industry might dissolve in itself, which shall come as no surprise.

Mckinsey 7s model

The Mckinsey 7s model is used to understand the structural organization of the business and its working by taking into consideration the various factors affecting the same.

System: Kodak worked in an extremely organized system with coordination on all fronts. Eastman Kodak had extremely appreciable organizational skills and the company followed the same structure and system for a long period until recently, when it had a change in its organisational structure, systems, and roles.

Skills: Kodak hired exceptionally skilled staff and started getting pickier during its peak. The first digital camera being invented in the company says a lot about its skills in terms of hardware. However, one of the drawbacks of kodak was its insufficient business skills in the board of marketing and directors.

Style: Kodak had an extremely creative team of advertisers and marketing workers who made it the brand it was in the past. Various skills of advertisement such as the kodak moments have had an impact on the lives of a large number of people helping the brand to create its own style.

Staff: The staff, as already mentioned, was highly skilled and up for tasks in terms of research, innovation, and development.

Structure: The same hierarchical structure that has been followed almost since Eastman was followed until recently and showcased an efficient set of systems.

Strategy: One of the reasons why the company did not see the failure coming was its lack of strategic skills. With a good business conscience, the company could have seen the digital camera take over the market. However, just like the paradox of strategy, Kodak did what it thought was right and stuck to a product that showed immense confidence and years of experience in developing the same. Even though it can’t have been stated as the wrong strategy, they didn’t do it right either.

Shared Values: One of Kodak’s biggest mistakes was to be conservative with a product that saw the hope of development almost every single day. Their shared values were strong and upheld integrity even during their peak years.

Strategic management cycle

The strategic management cycle explains how a particular strategy is formulated and later implemented and how its effects can be noticed after implementation. This is also an analysis of the digital camera strategy adopted by Kodak.

Strategy formulation: The first step in strategic planning is coming with one. In the case of Kodak, the major strategy that we need to investigate is the way they dealt with digital cameras and social media. Kodak did not realize the popularity or the heights that digital cameras would go to when it was first discovered. They did not want to let go of their main product of films, which was the reason they were popular as a company in the first place. This strategy of Kodak to continue developing films and reducing its prices while keeping the digital camera business on the side was one of the first mistakes in its strategy formulation. They did not anticipate the arrival of social media photo-sharing platforms either in keeping them far behind in business.

Planning: The next step of planning did not see a bright side either. They realized that films had no more development on their way and their research and development teams were convinced that there were no hopes.

Implementation: Implementation of the strategy was welcomed into the market with competition from other businesses that was almost nothing in front of Kodak during its bright years. These companies advertised digital markets while Kodak was accused of no further developments.

Review: On review of their strategy, we realize that the company had not only underestimated the market but had eventually lost hold over even its loyal consumers. Kodak has still not been able to recover from such a blow.

Results of the analysis

The paradox of strategy clearly implies that due to the flighty risks that a market holds are usually unpredictable by businesses, such a strategy, therefore, acts as a barrier to the development of the same. More times than not, the paradox of strategy is inevitable. With flexible business plans and extreme potential to foresee the market future, we can overcome the paradox. In the case of Kodak, the business plan and strategy taken proved itself outdated and irrelevant which would have seen immense success if not for the technological paradigm. However, in the case of Kodak, the paradox was completely avoidable. Kodak being the company that first came up with digital cameras should have seen the potential for such a development and invested in the same, but the realization came late when Kodak was losing its markets while other companies were making immense progress and investment in digital camera markets. The company had the potential and the resources but had no foresight for the transition that the future held for them and therefore ended up becoming a victim to the paradox.

Bhasin, H. (2019, May 5). SWOT analysis of Kodak – Kodak SWOT analysis . Marketing91. https://www.marketing91.com/swot-analysis-kodak/

Cunha, M. P. E., & Putnam, L. L. (2019). Paradox theory and the paradox of success. Strategic organization , 17 (1), 95-106.

Eastman Kodak - AnnualReports.com . (n.d.). Annualreports.Com. https://www.annualreports.com/Company/eastman-kodak

Eastman Kodak - Stock Price History | KODK . (n.d.). MacroTrends. https://www.macrotrends.net/stocks/charts/KODK/eastman-kodak/stock-price-history

KODAK stock price . (n.d.). Harker Research. https://harkerresearch.typepad.com/.a/6a00d8351451c553ef015434714a50970c-popup

Kodak’s Downfall Wasn’t About Technology . (2017, April 24). Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2016/07/kodaks-downfall-wasnt-about-technology

Kotter, J. (2012). Barriers to change: The real reason behind the Kodak downfall. Forbes, May , 2 .

Lucas Jr, H. C., & Goh, J. M. (2009). Disruptive technology: How Kodak missed the digital photography revolution. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems , 18 (1), 46-55.

Mckinsey 7s Framework Of Eastman Kodak Company . (n.d.). Essay48. https://www.essay48.com/2925-Eastman-Kodak-Company-Mckinsey-7s

Minds, B. (2020, December 15). Why Did Kodak Fail and What Can You Learn from its Demise? Medium. https://brand-minds.medium.com/why-did-kodak-fail-and-what-can-you-learn-from-its-failure-70b92793493c

Mui, C. (2020, July 14). How Kodak Failed . Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/chunkamui/2012/01/18/how-kodak-failed/?sh=6810c69f6f27

PetaPixel. (2018, June 14). A Brief History of Kodak: The Rise and Fall of a Camera Giant . https://petapixel.com/2018/06/14/a-brief-history-of-kodak-the-camera-giants-rise-and-fall/

Pigneur, Y. O. A. (n.d.). Why Your Company Might Be About To Have A Kodak Moment . Strategyzer. https://www.strategyzer.com/blog/posts/2016/1/5/why-your-company-might-be-about-to-have-a-kodak-moment

Prenatt, D., Ondracek, J., Saeed, M., & Bertsch, A. (2015). How Underdeveloped Decision Making and Poor Leadership Choices Led Kodak into Bankruptcy. Inspira: Journal of Modern Management & Entrepreneurship , 5 (1), 01-12.