How to Write a Poem, Step-by-Step

Sean Glatch | May 2, 2024 | 34 Comments

To learn how to write a poem step-by-step, let’s start where all poets start: the basics.

This article is an in-depth introduction to how to write a poem. We first answer the question, “What is poetry?” We then discuss the literary elements of poetry, and showcase some different approaches to the writing process—including our own seven-step process on how to write a poem step by step.

So, how do you write a poem? Let’s start with what poetry is.

How to Write a Poem: Contents

What Poetry Is

- Literary Devices

How to Write a Poem, in 7 Steps

How to write a poem: different approaches and philosophies.

- Okay, I Know How to Write a Good Poem. What Next?

It’s important to know what poetry is—and isn’t—before we discuss how to write a poem. The following quote defines poetry nicely:

“Poetry is language at its most distilled and most powerful.” —Former US Poet Laureate Rita Dove

Poetry Conveys Feeling

People sometimes imagine poetry as stuffy, abstract, and difficult to understand. Some poetry may be this way, but in reality poetry isn’t about being obscure or confusing. Poetry is a lyrical, emotive method of self-expression, using the elements of poetry to highlight feelings and ideas.

A poem should make the reader feel something.

In other words, a poem should make the reader feel something—not by telling them what to feel, but by evoking feeling directly.

Here’s a contemporary poem that, despite its simplicity (or perhaps because of its simplicity), conveys heartfelt emotion.

Poem by Langston Hughes

I loved my friend. He went away from me. There’s nothing more to say. The poem ends, Soft as it began— I loved my friend.

Poetry is Language at its Richest and Most Condensed

Unlike longer prose writing (such as a short story, memoir, or novel), poetry needs to impact the reader in the richest and most condensed way possible. Here’s a famous quote that enforces that distinction:

“Prose: words in their best order; poetry: the best words in the best order.” —Samuel Taylor Coleridge

So poetry isn’t the place to be filling in long backstories or doing leisurely scene-setting. In poetry, every single word carries maximum impact.

Poetry Uses Unique Elements

Poetry is not like other kinds of writing: it has its own unique forms, tools, and principles. Together, these elements of poetry help it to powerfully impact the reader in only a few words.

The elements of poetry help it to powerfully impact the reader in only a few words.

Most poetry is written in verse , rather than prose . This means that it uses line breaks, alongside rhythm or meter, to convey something to the reader. Rather than letting the text break at the end of the page (as prose does), verse emphasizes language through line breaks.

Poetry further accentuates its use of language through rhyme and meter. Poetry has a heightened emphasis on the musicality of language itself: its sounds and rhythms, and the feelings they carry.

These devices—rhyme, meter, and line breaks—are just a few of the essential elements of poetry, which we’ll explore in more depth now.

Understanding the Elements of Poetry

As we explore how to write a poem step by step, these three major literary elements of poetry should sit in the back of your mind:

- Rhythm (Sound, Rhyme, and Meter)

1. Elements of Poetry: Rhythm

“Rhythm” refers to the lyrical, sonic qualities of the poem. How does the poem move and breathe; how does it feel on the tongue?

Traditionally, poets relied on rhyme and meter to accomplish a rhythmically sound poem. Free verse poems —which are poems that don’t require a specific length, rhyme scheme, or meter—only became popular in the West in the 20th century, so while rhyme and meter aren’t requirements of modern poetry, they are required of certain poetry forms.

Poetry is capable of evoking certain emotions based solely on the sounds it uses. Words can sound sinister, percussive, fluid, cheerful, dour, or any other noise/emotion in the complex tapestry of human feeling.

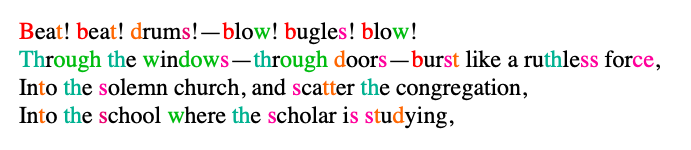

Take, for example, this excerpt from the poem “Beat! Beat! Drums!” by Walt Whitman:

Red — “b” sounds

Blue — “th” sounds

Green — “w” and “ew” sounds

Purple — “s” sounds

Orange — “d” and “t” sounds

This poem has a lot of percussive, disruptive sounds that reinforce the beating of the drums. The “b,” “d,” “w,” and “t” sounds resemble these drum beats, while the “th” and “s” sounds are sneakier, penetrating a deeper part of the ear. The cacophony of this excerpt might not sound “lyrical,” but it does manage to command your attention, much like drums beating through a city might sound.

To learn more about consonance and assonance, euphony and cacophony, onomatopoeia , and the other uses of sound, take a look at our article “12 Literary Devices in Poetry.”

https://writers.com/literary-devices-in-poetry

It would be a crime if you weren’t primed on the ins and outs of rhymes. “Rhyme” refers to words that have similar pronunciations, like this set of words: sound, hound, browned, pound, found, around.

Many poets assume that their poetry has to rhyme, and it’s true that some poems require a complex rhyme scheme. However, rhyme isn’t nearly as important to poetry as it used to be. Most traditional poetry forms—sonnets, villanelles , rimes royal, etc.—rely on rhyme, but contemporary poetry has largely strayed from the strict rhyme schemes of yesterday.

There are three types of rhymes:

- Homophony: Homophones are words that are spelled differently but sound the same, like “tail” and “tale.” Homophones often lead to commonly misspelled words .

- Perfect Rhyme: Perfect rhymes are word pairs that are identical in sound except for one minor difference. Examples include “slant and pant,” “great and fate,” and “shower and power.”

- Slant Rhyme: Slant rhymes are word pairs that use the same sounds, but their final vowels have different pronunciations. For example, “abut” and “about” are nearly-identical in sound, but are pronounced differently enough that they don’t completely rhyme. This is also known as an oblique rhyme or imperfect rhyme.

Meter refers to the stress patterns of words. Certain poetry forms require that the words in the poem follow a certain stress pattern, meaning some syllables are stressed and others are unstressed.

What is “stressed” and “unstressed”? A stressed syllable is the sound that you emphasize in a word. The bolded syllables in the following words are stressed, and the unbolded syllables are unstressed:

- Un• stressed

- Plat• i• tud• i•nous

- De •act•i• vate

- Con• sti •tu• tion•al

The pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables is important to traditional poetry forms. This chart, copied from our article on form in poetry , summarizes the different stress patterns of poetry.

2. Elements of Poetry: Form

“Form” refers to the structure of the poem. Is the poem a sonnet , a villanelle, a free verse piece, a slam poem, a contrapuntal, a ghazal , a blackout poem , or something new and experimental?

Form also refers to the line breaks and stanza breaks in a poem. Unlike prose, where the end of the page decides the line breaks, poets have control over when one line ends and a new one begins. The words that begin and end each line will emphasize the sounds, images, and ideas that are important to the poet.

To learn more about rhyme, meter, and poetry forms, read our full article on the topic:

https://writers.com/what-is-form-in-poetry

3. Elements of Poetry: Literary Devices

“Poetry: the best words in the best order.” — Samuel Taylor Coleridge

How does poetry express complex ideas in concise, lyrical language? Literary devices—like metaphor, symbolism , juxtaposition , irony , and hyperbole—help make poetry possible. Learn how to write and master these devices here:

https://writers.com/common-literary-devices

To condense the elements of poetry into an actual poem, we’re going to follow a seven-step approach. However, it’s important to know that every poet’s process is different. While the steps presented here are a logical path to get from idea to finished poem, they’re not the only tried-and-true method of poetry writing. Poets can—and should!—modify these steps and generate their own writing process.

Nonetheless, if you’re new to writing poetry or want to explore a different writing process, try your hand at our approach. Here’s how to write a poem step by step!

1. Devise a Topic

The easiest way to start writing a poem is to begin with a topic.

However, devising a topic is often the hardest part. What should your poem be about? And where can you find ideas?

Here are a few places to search for inspiration:

- Other Works of Literature: Poetry doesn’t exist in a vacuum—it’s part of a larger literary tapestry, and can absolutely be influenced by other works. For example, read “The Golden Shovel” by Terrance Hayes , a poem that was inspired by Gwendolyn Brooks’ “We Real Cool.”

- Real-World Events: Poetry, especially contemporary poetry, has the power to convey new and transformative ideas about the world. Take the poem “A Cigarette” by Ilya Kaminsky , which finds community in a warzone like the eye of a hurricane.

- Your Life: What would poetry be if not a form of memoir? Many contemporary poets have documented their lives in verse. Take Sylvia Plath’s poem “Full Fathom Five” —a daring poem for its time, as few writers so boldly criticized their family as Plath did.

- The Everyday and Mundane: Poetry isn’t just about big, earth-shattering events: much can be said about mundane events, too. Take “Ode to Shea Butter” by Angel Nafis , a poem that celebrates the beautiful “everydayness” of moisturizing.

- Nature: The Earth has always been a source of inspiration for poets, both today and in antiquity. Take “Wild Geese” by Mary Oliver , which finds meaning in nature’s quiet rituals.

- Writing Exercises: Prompts and exercises can help spark your creativity, even if the poem you write has nothing to do with the prompt! Here’s 24 writing exercises to get you started.

At this point, you’ve got a topic for your poem. Maybe it’s a topic you’re passionate about, and the words pour from your pen and align themselves into a perfect sonnet! It’s not impossible—most poets have a couple of poems that seemed to write themselves.

However, it’s far more likely you’re searching for the words to talk about this topic. This is where journaling comes in.

Sit in front of a blank piece of paper, with nothing but the topic written on the top. Set a timer for 15-30 minutes and put down all of your thoughts related to the topic. Don’t stop and think for too long, and try not to obsess over finding the right words: what matters here is emotion, the way your subconscious grapples with the topic.

At the end of this journaling session, go back through everything you wrote, and highlight whatever seems important to you: well-written phrases, poignant moments of emotion, even specific words that you want to use in your poem.

Journaling is a low-risk way of exploring your topic without feeling pressured to make it sound poetic. “Sounding poetic” will only leave you with empty language: your journal allows you to speak from the heart. Everything you need for your poem is already inside of you, the journaling process just helps bring it out!

Learn more about keeping a daily journal here:

How to Start Journaling: Practical Advice on How to Journal Daily

3. Think About Form

As one of the elements of poetry, form plays a crucial role in how the poem is both written and read. Have you ever wanted to write a sestina ? How about a contrapuntal, or a double cinquain, or a series of tanka? Your poem can take a multitude of forms, including the beautifully unstructured free verse form; while form can be decided in the editing process, it doesn’t hurt to think about it now.

4. Write the First Line

After a productive journaling session, you’ll be much more acquainted with the state of your heart. You might have a line in your journal that you really want to begin with, or you might want to start fresh and refer back to your journal when you need to! Either way, it’s time to begin.

What should the first line of your poem be? There’s no strict rule here—you don’t have to start your poem with a certain image or literary device. However, here’s a few ways that poets often begin their work:

- Set the Scene: Poetry can tell stories just like prose does. Anne Carson does just this in her poem “Lines,” situating the scene in a conversation with the speaker’s mother.

- Start at the Conflict : Right away, tell the reader where it hurts most. Margaret Atwood does this in “Ghost Cat,” a poem about aging.

- Start With a Contradiction: Juxtaposition and contrast are two powerful tools in the poet’s toolkit. Joan Larkin’s poem “Want” begins and ends with these devices. Carlos Gimenez Smith also begins his poem “Entanglement” with a juxtaposition.

- Start With Your Title: Some poets will use the title as their first line, like Ron Padgett’s poem “Ladies and Gentlemen in Outer Space.”

There are many other ways to begin poems, so play around with different literary devices, and when you’re stuck, turn to other poetry for inspiration.

5. Develop Ideas and Devices

You might not know where your poem is going until you finish writing it. In the meantime, stick to your literary devices. Avoid using too many abstract nouns, develop striking images, use metaphors and similes to strike interesting comparisons, and above all, speak from the heart.

6. Write the Closing Line

Some poems end “full circle,” meaning that the images the poet used in the beginning are reintroduced at the end. Gwendolyn Brooks does this in her poem “my dreams, my work, must wait till after hell.”

Yet, many poets don’t realize what their poems are about until they write the ending line . Poetry is a search for truth, especially the hard truths that aren’t easily explained in casual speech. Your poem, too, might not be finished until it comes across a necessary truth, so write until you strike the heart of what you feel, and the poem will come to its own conclusion.

7. Edit, Edit, Edit!

Do you have a working first draft of your poem? Congratulations! Getting your feelings onto the page is a feat in itself.

Yet, no guide on how to write a poem is complete without a note on editing. If you plan on sharing or publishing your work, or if you simply want to edit your poem to near-perfection, keep these tips in mind.

- Adjectives and Adverbs: Use these parts of speech sparingly. Most imagery shouldn’t rely on adjectives and adverbs, because the image should be striking and vivid on its own, without too much help from excess language.

- Concrete Line Breaks: Line breaks help emphasize important words, making certain images and themes clearer to the reader. As a general rule, most of your lines should start and end with concrete words—nouns and verbs especially.

- Stanza Breaks: Stanzas are like paragraphs to poetry. A stanza can develop a new idea, contrast an existing idea, or signal a transition in the poem’s tone. Make sure each stanza clearly stands for something as a unit of the poem.

- Mixed Metaphors: A mixed metaphor is when two metaphors occupy the same idea, making the poem unnecessarily difficult to understand. Here’s an example of a mixed metaphor: “a watched clock never boils.” The meaning can be discerned, but the image remains unclear. Be wary of mixed metaphors—though some poets (like Shakespeare) make them work, they’re tricky and often disruptive.

- Abstractions: Above all, avoid using excessively abstract language. It’s fine to use the word “love” 2 or 3 times in a poem, but don’t use it twice in every stanza. Let the imagery in your poem express your feelings and ideas, and only use abstractions as brief connective tissue in otherwise-concrete writing.

Lastly, don’t feel pressured to “do something” with your poem. Not all poems need to be shared and edited. Poetry doesn’t have to be “good,” either—it can simply be a statement of emotions by the poet, for the poet. Publishing is an admirable goal, but also, give yourself permission to write bad poems, unedited poems, abstract poems, and poems with an audience of one. Write for yourself—editing is for the other readers.

Poetry is the oldest literary form, pre-dating prose, theater, and the written word itself. As such, there are many different schools of thought when it comes to writing poetry. You might be wondering how to write a poem through different methods and approaches: here’s four philosophies to get you started.

How to Write a Poem: Poetry as Emotion

If you asked a Romantic Poet “what is poetry?”, they would tell you that poetry is the spontaneous emotion of the soul.

The Romantic Era viewed poetry as an extension of human emotion—a way of perceiving the world through unbridled creativity, centered around the human soul. While many Romantic poets used traditional forms in their poetry, the Romantics weren’t afraid to break from tradition, either.

To write like a Romantic, feel—and feel intensely. The words will follow the emotions, as long as a blank page sits in front of you.

How to Write a Poem: Poetry as Stream of Consciousness

If you asked a Modernist poet, “What is poetry?” they would tell you that poetry is the search for complex truths.

Modernist Poets were keen on the use of poetry as a window into the mind. A common technique of the time was “Stream of Consciousness,” which is unfiltered writing that flows directly from the poet’s inner dialogue. By tapping into one’s subconscious, the poet might uncover deeper truths and emotions they were initially unaware of.

Depending on who you are as a writer, Stream of Consciousness can be tricky to master, but this guide covers the basics of how to write using this technique.

How to Write a Poem: Mindfulness

Mindfulness is a practice of documenting the mind, rather than trying to control or edit what it produces. This practice was popularized by the Beat Poets , who in turn were inspired by Eastern philosophies and Buddhist teachings. If you asked a Beat Poet “what is poetry?”, they would tell you that poetry is the human consciousness, unadulterated.

To learn more about the art of leaving your mind alone , take a look at our guide on Mindfulness, from instructor Marc Olmsted.

https://writers.com/mindful-writing

How to Write a Poem: Poem as Camera Lens

Many contemporary poets use poetry as a camera lens, documenting global events and commenting on both politics and injustice. If you find yourself itching to write poetry about the modern day, press your thumb against the pulse of the world and write what you feel.

Additionally, check out these two essays by Electric Literature on the politics of poetry:

- What Can Poetry Do That Politics Can’t?

- Why All Poems Are Political (TL;DR: Poetry is an urgent expression of freedom).

Okay, I Know How to Write a Poem. What Next?

Poetry, like all art forms, takes practice and dedication. You might write a poem you enjoy now, and think it’s awfully written 3 years from now; you might also write some of your best work after reading this guide. Poetry is fickle, but the pen lasts forever, so write poems as long as you can!

Once you understand how to write a poem, and after you’ve drafted some pieces that you’re proud of and ready to share, here are some next steps you can take.

Publish in Literary Journals

Want to see your name in print? These literary journals house some of the best poetry being published today.

https://writers.com/best-places-submit-poetry-online

Assemble and Publish a Manuscript

A poem can tell a story. So can a collection of poems. If you’re interested in publishing a poetry book, learn how to compose and format one here:

https://writers.com/poetry-manuscript-format

How to Write a Poem: Join a Writing Community

Writers.com is an online community of writers, and we’d love it if you shared your poetry with us! Join us on Facebook and check out our upcoming poetry courses .

Poetry doesn’t exist in a vacuum, it exists to educate and uplift society. The world is waiting for your voice, so find a group and share your work!

Sean Glatch

34 comments.

super useful! love these articles 💕

Finally found a helpful guide on Poetry’. For many year, I have written and filed numerous inspired pieces from experiences and moment’s of epiphany. Finally, looking forward to convertinb to ‘poetry format’. THANK YOU, KINDLY. 🙏🏾

Indeed, very helpful, consize. I could not say more than thank you.

I’ve never read a better guide on how to write poetry step by step. Not only does it give great tips, but it also provides helpful links! Thank you so much.

Thank you very much, Hamna! I’m so glad this guide was helpful for you.

Best guide so far

Very inspirational and marvelous tips

Thank you super tips very helpful.

I have never gone through the steps of writing poetry like this, I will take a closer look at your post.

Beautiful! Thank you! I’m really excited to try journaling as a starter step x

[…] How to Write a Poem, Step-by-Step […]

This is really helpful, thanks so much

Extremely thorough! Nice job.

Thank you so much for sharing your awesome tips for beginner writers!

People must reboot this and bookmark it. Your writing and explanation is detailed to the core. Thanks for helping me understand different poetic elements. While reading, actually, I start thinking about how my husband construct his songs and why other artists lack that organization (or desire to be better). Anyway, this gave me clarity.

I’m starting to use poetry as an outlet for my blogs, but I also have to keep in mind I’m transitioning from a blogger to a poetic sweet kitty potato (ha). It’s a unique transition, but I’m so used to writing a lot, it’s strange to see an open blog post with a lot of lines and few paragraphs.

Anyway, thanks again!

I’m happy this article was so helpful, Eternity! Thanks for commenting, and best of luck with your poetry blog.

Yours in verse, Sean

One of the best articles I read on how to write poems. And it is totally step by step process which is easy to read and understand.

Thanks for the step step explanation in how to write poems it’s a very helpful to me and also for everyone one. THANKYOU

Totally detailed and in a simple language told the best way how to write poems. It is a guide that one should read and follow. It gives the detailed guidance about how to write poems. One of the best articles written on how to write poems.

what a guidance thank you so much now i can write a poem thank you again again and again

The most inspirational and informative article I have ever read in the 21st century.It gives the most relevent,practical, comprehensive and effective insights and guides to aspiring writers.

Thank you so much. This is so useful to me a poetry

[…] Write a short story/poem (Here are some tips) […]

It was very helpful and am willing to try it out for my writing Thanks ❤️

Thank you so much. This is so helpful to me, and am willing to try it out for my writing .

Absolutely constructive, direct, and so useful as I’m striving to develop a recent piece. Thank you!

thank you for your explanation……,love it

Really great. Nothing less.

I can’t thank you enough for this, it touched my heart, this was such an encouraging article and I thank you deeply from my heart, I needed to read this.

great teaching Did not know all that in poetry writing

This was very useful! Thank you for writing this.

After reading a Charles Bukowski poem, “My Cats,” I found you piece here after doing a search on poetry writing format. Your article is wonderful as is your side article on journaling. I want to dig into both and give it another go another after writing poetry when I was at university. Thank you!

Thanks for reading, Vicki! Let us know how we can support your writing journey. 🙂

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Definition of Poem

A poem is a collection of spoken or written words that expresses ideas or emotions in a powerfully vivid and imaginative style . A poem is comprised of a particular rhythmic and metrical pattern. In fact, it is a literary technique that is different from prose or ordinary speech, as it is either in a metrical pattern or in free verse . Writers or poets express their emotions through this medium more easily, as they face difficulty when expressing through some other medium. It serves the purpose of light to take the readers towards the right path. Also, sometimes it teaches them a moral lesson through sugar-coated language.

Types of Poem

- Haiku – A type of Japanese poem consisting of three unrhymed lines, with mostly five, seven, and five syllables in each line.

- Free Verse – Consists of non–rhyming lines, without any metrical pattern, but which follow a natural rhythm .

- Epic – A form of a lengthy poem, often written in blank verse , in which the poet shows a protagonist in the action of historical significance or a great mythic.

- Ballad – A type of narrative poem in which a story often talks about folk or legendary tales. It may take the form of a moral lesson or a song.

- Sonnet – It is a form of a lyrical poem containing fourteen lines, with iambic pentameter and tone or mood changes after the eighth line.

- Elegy – A melancholic poem in which the poet laments the death of a subject , though he gives consolation towards the end.

- Epitaph – A small poem used as an inscription on a tombstone.

- Hymn – This type of poem praises spirituality or God’s splendor.

- Limerick – This is a type of humorous poem with five anapestic lines in which the first, second, and fifth lines have three feet, and the third and fourth lines have two feet, with a strict rhyme scheme of AABA.

- Villanelle – A French-styled poem with nineteen lines, composed of the three-line stanza , with five tercets and a final quatrain . It uses a refrain at the first and third lines of each stanza.

How to Write a Poem’s Analysis?

There are several ways of writing an analysis of a poem. Specifically, when analyzing a poem from the point of view of kids, it is considered for its message, theme , main idea , rhythm, rhyme scheme, diction , sound devices , and figures of speech used in it. All these techniques or poetic devices explain the major idea behind the writing of that specific poem.

Types of Poems

There are several types of poems. Some are specifically English types, while some have been imported from other cultures. For example, epic has entered English literature from the classical Greece culture while ode , lyric , and ballad are specifically English. Similarly, sonnet , haiku , villanelle , sestina , quatrain, rime, and limerick are some other types of poems.

Even blank verse poems and rhymed poems are two other categories that are based on the use of rhyme scheme, while narrative poems and soliloquies are based on the type of language. Ode, lyric, and song are based on the structure.

Parts of a Poem

A poem is broken down into parts to make it easy to analyze. Therefore, the very first part is the author or the poet who has composed that piece. The structural parts are stanzas, quatrains, verses, lines, rhyme, and rhythm, while linguistic parts are figures of speech and other literary and sound devices.

Examples of Poem in Literature

Example #1: while you decline to cry by ō no yasumaro.

“While you decline to cry, high on the mountainside a single stalk of plume grass wilts.”

(Loose translation by Michael R. Burch)

This poem contains three lines, which is the typical structure of a haiku poem. It does not follow any formal rhyme scheme or proper rhythmical pattern.

Example #2: The Song of Hiawatha by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

“By the shore of Gitchie Gumee, By the shining Big-Sea-Water, At the doorway of his wigwam, In the pleasant Summer morning, Hiawatha stood and waited…”

These are a few lines from The Song of Hiawatha , a classic epic poem that presents an American Indian legend of a loving, brave, patriotic, and stoic hero , but which bears resemblance to Greek myths of Homer. Longfellow tells of the sorrows and triumphs of the Indian tribes in detail in this lengthy poem. Therefore, this is a fine example of a modern epic, though other epics include Paradise Lost by John Milton and Iliad by Homer.

Example #3: After the Sea-Ship by Walt Whitman

Free Verse Poem

“After the Sea-Ship—after the whistling winds; After the white-gray sails, taut to their spars and ropes, Below, a myriad, myriad waves, hastening, lifting up their necks, Tending in ceaseless flow toward the track of the ship: Waves of the ocean, bubbling and gurgling, blithely prying…”

This poem neither has rhyming lines nor does it adhere to a particular metrical plan. Hence, it is free of artificial expression. It has rhythm and a variety of rhetorical devices used for sounds, such as assonance and consonance .

Example #4: La Belle Dame sans Merci by John Keats

“O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms, Alone and palely loitering? The sedge has wither’d from the lake, And no birds sing … And this is why I sojourn here Alone and palely loitering, Though the sedge is wither’d from the lake, And no birds sing.”

This poem presents a perfect example of a ballad—a folk-style poem that typically narrates a love story. The language of this poem is simple. It contains twelve stanzas, with four quatrains and a rhyme scheme of ABCB.

Function of Poem

The main function of a poem is to convey an idea or emotion in beautiful language. It paints a picture of what the poet feels about a thing, person, idea, concept, or even an object . Poets grab the attention of the audience through the use of vivid imagery , emotional shades, figurative language , and other rhetorical devices. However, the supreme function of a poem is to transform imagery and words into verse form, to touch the hearts and minds of the readers. They can easily arouse the sentiments of their readers through versification. In addition, poets evoke imaginative awareness about things by using a specific diction, sound, and rhythm.

Synonyms of Poem

There are several pieces that come very close to a poem in meanings such as composition, creation, song, ballad, verse, lyric, or even rhyme but every word has its own nuances. Therefore, they are not interchangeable or substituted.

Related posts:

- Narrative Poem

- I Am Offering this Poem

- Great Allegorical Poem Examples

- 10 Best Free-Verse Poem Examples For Kids

- O Nightingale

- Mother to Son

- 10 Beautiful Allusions in Poetry

- Annabel Lee

- My Last Duchess

- Mother Earth

- Mother of Pearl

- She Walks in Beauty

- O Captain! My Captain!

- The Waste Land

- A Dream within a Dream

- I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud

- The New Colossus

- Death, Be Not Proud

- Dulce et Decorum Est

- When I Have Fears That I May Cease to Be

- Love’s Philosophy

- Ode on a Grecian Urn

- Little Bo-Peep

- A Poison Tree

- Pied Beauty

- God’s Grandeur

- My Papa’s Waltz

- When You Are Old

- The Tide Rises, the Tide Falls

- Thanatopsis

- Mary Had a Little Lamb

- Hush Little Baby, Don’t Say a Word

- Nothing Gold Can Stay

- The Chimney Sweeper

- See It Through

- Baa, Baa, Black Sheep

- The Emperor of Ice-Cream

- Success is Counted Sweetest

- The Wreck of the Hesperus

- Lady Lazarus

- The Twelve Days of Christmas

- On Being Brought from Africa to America

- Ballad of Birmingham

- I Hear America Singing

- Much Madness is Divinest Sense

- Of Modern Poetry

- Song of the Open Road

- From Endymion

- Little Miss Muffet

- O Me! O Life!

- Insensibility

- The Albatross

- My Life Had Stood – a Loaded Gun

- In the Desert

- Loveliest of Trees, the Cherry Now

- Neutral Tones

- Blow, Blow, Thou Winter Wind

- On My First Son

- The Man He Killed

- Verses upon the Burning of Our House

- The Song of Wandering Aengus

- The Mother

- Frost at Midnight

- There’s a Certain Slant of Light

- The Haunted Palace

- On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer

- The Convergence of the Twain

- Composed upon Westminster Bridge

- Concord Hymn

- In Memoriam A. H. H. OBIIT MDCCCXXXIII: 27

- Song: To Celia

- Love Among The Ruins

- Carrion Comfort

- Fra Lippo Lippi

- Speech: “Is this a dagger which I see before me

- Que Sera Sera

- The Black-Faced Sheep

Post navigation

- Literary Terms

- Definition & Examples

- When & How to Write Poetry

I. What is Poetry?

Poetry is a type of literature based on the interplay of words and rhythm. It often employs rhyme and meter (a set of rules governing the number and arrangement of syllables in each line). In poetry, words are strung together to form sounds, images, and ideas that might be too complex or abstract to describe directly.

Poetry was once written according to fairly strict rules of meter and rhyme, and each culture had its own rules. For example, Anglo-Saxon poets had their own rhyme schemes and meters, while Greek poets and Arabic poets had others. Although these classical forms are still widely used today, modern poets frequently do away with rules altogether – their poems generally do not rhyme, and do not fit any particular meter. These poems, however, still have a rhythmic quality and seek to create beauty through their words.

The opposite of poetry is “prose” – that is, normal text that runs without line breaks or rhythm. This article, for example, is written in prose.

II. Examples and Explanation

Of all creatures that breathe and move upon the earth,

nothing is bred that is weaker than man.

(Homer, The Odyssey)

The Greek poet Homer wrote some of the ancient world’s most famous literature. He wrote in a style called epic poetry , which deals with gods, heroes, monsters, and other large-scale “epic” themes . Homer’s long poems tell stories of Greek heroes like Achilles and Odysseus, and have inspired countless generations of poets, novelists, and philosophers alike.

Poetry gives powerful insight into the cultures that create it. Because of this, fantasy and science fiction authors often create poetry for their invented cultures. J.R.R. Tolkien famously wrote different kinds of poetry for elves, dwarves, hobbits, and humans, and the rhythms and subject matter of their poetry was supposed to show how these races differed from one another. In a more humorous vein, many Star Trek fans have taken to writing love poetry in the invented Klingon language.

III. The Importance of Poetry

Poetry is probably the oldest form of literature, and probably predates the origin of writing itself. The oldest written manuscripts we have are poems, mostly epic poems telling the stories of ancient mythology. Examples include the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Vedas (sacred texts of Hinduism). This style of writing may have developed to help people memorize long chains of information in the days before writing. Rhythm and rhyme can make the text more memorable, and thus easier to preserve for cultures that do not have a written language.

Poetry can be written with all the same purposes as any other kind of literature – beauty, humor, storytelling, political messages, etc.

IV. Examples in of Poetry Literature

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); I think that I shall never see –> A a poem lovely as a tree… –> A poems are made by fools like me, –> B but only God can make a tree. –> B (Joyce Kilmer, Trees )

This is an excerpt from Joyce Kilmer’s famous short poem. The poem employs a fairly standard rhyme scheme (AABB, lines 1 and 2 rhymes together and lines 3 and 4 rhymes together), and a meter called “iambic tetrameter,” which is commonly employed in children’s rhymes.

I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked, dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix, angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night, who poverty and tatters and hollow-eyed and high sat up smoking… (Alan Ginsberg, Howl)

These are the first few lines of Howl , one of the most famous examples of modern “free verse” poetry. It has no rhyme, and no particular meter. But its words still have a distinct, rhythmic quality, and the line breaks encapsulate the meaning of the poem. Notice how the last word of each line contributes to the imagery of a corrupt, ravaged city (“madness, naked, smoking”), with one exception: “heavenly.” This powerful juxtaposition goes to the heart of Ginsburg’s intent in writing the poem – though what that intent is, you’ll have to decide for yourself.

In the twilight rain, these brilliant-hued hibiscus – A lovely sunset

This poem by the Japanese poet Basho is a haiku . This highly influential Japanese style has no rhymes, but it does have a very specific meter – five syllables in the first line, seven in the second line, and five in the third line.

V. Examples of Poetry in Popular Culture

Rapping originated as a kind of performance poetry. In the 1960s and 70s, spoken word artists like Gil Scott-Heron began performing their poems over live or synthesized drumbeats, a practice that sparked all of modern hip hop. Even earlier, the beat poets of the 1950s sometimes employed drums in their readings.

Some of the most famous historical poems have been turned into movies or inspired episodes of television shows. Beowulf , for example, is an Anglo-Saxon epic poem that has spawned at least 8 film adaptations, most recently a 2007 animated film starring Angelina Jolie and Anthony Hopkins. Edgar Allen Poe’s The Raven has also inspired many pop culture spinoffs with its famous line, “Nevermore.”

VI. Related Terms (with examples)

Nearly all poems are written in verse – that is, they have line breaks and meter (rhythm). But verse is also used in other areas of literature. For example, Shakespeare’s characters often speak in verse. Their dialogue is separated into rhythmic lines just like a song, but they are supposed to be speaking normally.

List of Terms

- Alliteration

- Amplification

- Anachronism

- Anthropomorphism

- Antonomasia

- APA Citation

- Aposiopesis

- Autobiography

- Bildungsroman

- Characterization

- Circumlocution

- Cliffhanger

- Comic Relief

- Connotation

- Deus ex machina

- Deuteragonist

- Doppelganger

- Double Entendre

- Dramatic irony

- Equivocation

- Extended Metaphor

- Figures of Speech

- Flash-forward

- Foreshadowing

- Intertextuality

- Juxtaposition

- Literary Device

- Malapropism

- Onomatopoeia

- Parallelism

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Personification

- Point of View

- Polysyndeton

- Protagonist

- Red Herring

- Rhetorical Device

- Rhetorical Question

- Science Fiction

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Synesthesia

- Turning Point

- Understatement

- Urban Legend

- Verisimilitude

- Essay Guide

- Cite This Website

What Is a Poem? Definition, Usage, and Literary Examples

Poem definition.

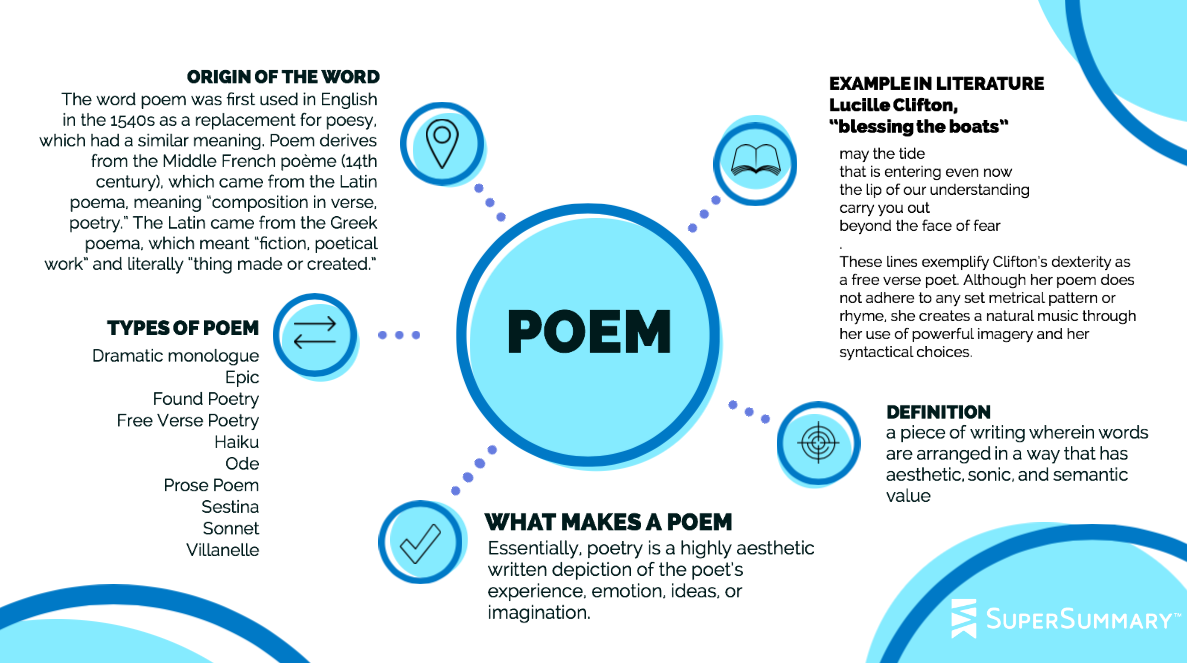

A poem (POH-im) is a piece of writing wherein words are arranged in a way that has aesthetic, sonic, and semantic value. Poems are carefully composed to convey ideas, emotions, and/or experiences vividly through literal and figurative imagery , as well as the frequent use of formal elements such as stanzaic structure, rhyme , and meter .

The word poem was first used in English in the 1540s as a replacement for poesy , which had a similar meaning. Poem derives from the Middle French poème (14th century), which came from the Latin poema , meaning “composition in verse, poetry.” The Latin came from the Greek poema , which meant “fiction, poetical work” and literally “thing made or created.”

What Makes a Poem

It’s not easy to determine set criteria for what makes a poem. Traditionally, people used to categorize poetry as literature written only in rhymed verse, but that isn’t correct. Although historically poetry adhered to set formulas of rhyme and meter, free verse —the most common form of contemporary poetry—does not. Free verse is unmetered and either does not rhyme at all or tends to use slant rhymes. In addition to free verse, many other types of poetry don’t rhyme or follow metrical patterns.

Additionally, the definition of poetry as literary work that is written in verse—as opposed to prose , the style novels are typically written in—is also no longer true. There are novels written in verse, just as there’s an entire genre of poetry written in prose (prose poetry). There’s also a type of poetry that consists of only one sentence written out as a single line (the monostitch).

Unlike many other literary forms, there’s no universally accepted collection of elements that any given poem must contain. Poetry lends itself to highly romantic, dramatic definitions. Consider Jim Harrison ’s definition, “the language your soul would speak if you could teach your soul to speak,” or Percy Bysshe Shelley’s, “the expression of the imagination. ”

Essentially, poetry is a highly aesthetic written depiction of the poet’s experience, emotion, ideas, or imagination. Although any given poem need not contain all of these elements, poetry does consistently employ literary devices such as rhyme, meter, imagery, metaphor , simile , onomatopoeia , alliteration , and refrain to engage the reader.

Types of Poem

There are many different types of poems, but the following are some of the most common.

- A dramatic monologue is a type of poem where a character speaks without interruption and reveals surprising information about themselves or their situation. This type of work is also called a persona poem.

- Epics are long poetic works that tell a story, typically from the third-person point of view . They tend to follow a idyllic hero who represents their culture, and the plot is usually of cultural, historical, and/or religious importance.

- Found poetry is composed entirely from snippets of text taken from outside sources; for example, movie titles or lines from a newspaper horoscope column. In addition to typical found poems, there are also centos, which are made up of 100 lines from 100 other poems, and erasures, where a poet takes a page of text and crosses out most words, creating a poem from the ones that remain.

- Free verse poetry, as stated, does not follow any set metrical pattern or rhyme scheme . Instead, the poet is free to compose the poem however they wish without following any rules.

- Haiku is a type of Japanese poetry consisting of a tercet (three-line stanza) where the first line has a syllabic count of five, the second line consists of seven syllables, and the final third line returns to the five count. These three lines do not rhyme.

- Odes are lyric poems, often elevated or formal in manner, and written in praise of someone or something. There are three types of odes: Pindaric, Horatian, and irregular.

- Prose poems are, of course, poems written in prose. Rather than using line breaks and stanzaic structure, these poems follow the formatting conventions of prose and are written in a paragraph or series of paragraphs.

- Sestinas are poems comprised of seven stanzas that follow a strict, complex structure. The first six stanzas are sestets (six-line stanzas), and the final stanza is a tercet. The last word of each line of the first six stanzas must repeat in a certain pattern, and those six end-words all recur in the final stanza (the envoi) according to a specific order.

- Sonnets are 14-line poems that follow set patterns of rhyme and meter and whose mood or tone must change after the eighth line (the volta). There are two primary types of sonnets: the English (or Shakespearean ) sonnet and the Italian (or Petrarchan) sonnet.

- Villanelles are French poems composed of 19 lines. These poems contain five tercets (three-line stanzas) and a final quatrain (four-line stanza). They utilize two repeating rhymes and two refrains.

Notable Poets

- John Ashbery, “ Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror ”

- Charles Baudelaire, “ The Cat ”

- Basho, “ In Kyoto ”

- William Blake, “ The Tyger "

- Elizabeth Barrett Browning, “ How Do I Love Thee? "

- Robert Browning, “ My Last Duchess ”

- Gwendolyn Brooks, “ We Real Cool ”

- Robert Burns, “ To a Haggis ”

- Samuel Taylor Coleridge, “ The Rime of the Ancient Mariner ”

- Emily Dickinson, “ My Life had stood-a Loaded Gun ”

- John Donne, “ Death, be not proud ”

- T.S. Eliot, “ The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock ”

- Robert Frost, “ Desert Places ”

- Homer, The Odyssey

- Langston Hughes, “ Theme for English B ”

- Allen Ginsberg, “ Howl ”

- John Keats, “ Ode to a Nightingale ”

- Edna St. Vincent Millay, “ Recuerdo ”

- Ovid, The Metamorphoses

- Pablo Neruda, “ The Song of Despair ”

- Rumi, “ Where did the handsome beloved go? ”

- Sappho, “ Fragment ”

- William Shakespeare, “ Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? "

- Percy Bysshe Shelley, “ Ozymandias ”

- Sylvia Plath, “ Lady Lazarus ”

- Alfred Lord Tennyson, “ The Charge of the Light Brigade ”

- Walt Whitman, “ When Lilacs Kast in the Dooryard Bloom’d ”

- William Wordsworth, “ I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud ”

- William Butler Yeats, “ The Second Coming ”

Examples of Poems

1. Lucille Clifton, “blessing the boats”

Clifton opens her famous poem with the lines:

may the tide

that is entering even now

the lip of our understanding

carry you out

beyond the face of fear

These lines exemplify her dexterity as a free verse poet. Although her poem doesn’t adhere to any set metrical pattern or rhyme, she creates a natural music through her use of powerful imagery and her syntactical choices.

2. Elizabeth Bishop, “The Art of Losing”

Bishop’s poem was originally written in free verse; however, during revisions, she decided it would be more powerful with the rhyme and refrain elements of the villanelle form. Her opening stanza sets up the composition that all subsequent stanzas amplify:

The art of losing isn’t hard to master;

so many things seem filled with the intent

to be lost that their loss is no disaster.

Lose something every day. Accept the fluster

of lost door keys, the hour badly spent.

The art of losing isn’t hard to master.

The first refrain is the first line of the first stanza , which appears as the last line in the second stanza. You can also see the beginning of Bishop’s ABA rhyme scheme.

3. Ron Padgett, “Haiku”

Ron Padgett’s poem is a clever embodiment of the eponymous form. The poem reads, in its entirety:

First: five syllables.

Second: seven syllables.

Third: five syllables.

Padgett’s title states the form his poem will take. His short work both tells the readers what structure a haiku requires while simultaneously perfectly fulfilling those requirements.

4. Mattea Harvey, “Implications for Modern Life”

Harvey’s prose poem eschews line breaks and stanza breaks in favor of standard paragraph formatting. In her first few lines, Harvey presents a strong visual situation described in prose:

The ham flowers have veins and are rimmed in rind, each petal a little meat sunset. I deny all connection with the ham flowers, the barge floating by loaded with lard, the white flagstones like platelets in the blood-red road. I’ll put the calves in coats so the ravens can’t gore them, bandage up the cut gate and when the wind rustles its muscles, I’ll gather the seeds and burn them.

Throughout the poem, she utilizes other standard elements of poetry— alliteration , imagery , metaphor , and personification—which give her work the same sonic elegance and vivid visual power that readers are accustomed to seeing in poetry.

5. Nate Marshall, “pallbearers”

In the first stanza, Marshall sets up the sestina structure he must follow:

Dom, Kenny, Shaun, Bark & i were close as a coffin.

promised we would always be tight.

we made it to every middle school dance.

weaving through crowds of kids we kept moving

behind a nervous girl’s hips, mesmerized by the split

of skirts & smiles at our request. we didn’t know much.

The last word of each line— coffin , tight , dance , moving , split , and much —reappear at the end of different lines in subsequent stanzas of the poem, following the traditional sestina structure. Unlike many sestinas, however, Marshall uses a more experimental approach to capitalization, using lowercase letters at the beginning of each sentence and capitalizing only the names of the speaker’s friends as another way to emphasize their importance.

6. William Shakespeare, “Sonnet XXIX”

Shakespeare’s sonnet opens with his speaker declaring:

When, in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes,

I all alone beweep my outcast state

And trouble deaf heaven with my bootless cries

And look upon myself and curse my fate

These opening four lines are written in iambic pentameter, which means that there is a pattern of five metrical feet per line and each foot consists of a short, unstressed syllable followed by a long, stressed syllable. This metrical pattern is a required part of the English sonnet, as is the rhyme scheme of ABAB that these lines follow. Later in the sonnet, at the eighth line, the poem takes a turn and shifts into a new direction, giving it a sense of resolution.

Further Resources on Poems

The poet Mark Yakich wrote a lovely analysis of poetry for The Atlantic online ’s “Object Lessons” series.

Matthew Zapruder has an excellent book explaining the importance of poetry, as well as easy ways to understand it.

The Academy of American Poets’ website is an excellent source for additional poetry information, as is the website for The Poetry Foundation .

The Best American Poetry anthology series runs a blog full of original posts by poets, as well as interviews, essays about the world of poetry, new poems, and other poetry commentary.

Related Terms

- National Poetry Month

- Materials for Teachers

- Literary Seminars

- American Poets Magazine

Main navigation

- Academy of American Poets

User account menu

Explore the glossary of poetic terms.

Page submenu block

- literary seminars

- materials for teachers

- poetry near you

Poetry is a form of writing vital to culture, art, and life.

From A Poet’s Glossary

The following definition of the term poetry is reprinted from A Poet’s Glossary by Edward Hirsch.

An inexplicable (though not incomprehensible) event in language; an experience through words. Jorge Luis Borges believed that “poetry is something that cannot be defined without oversimplifying it. It would be like attempting to define the color yellow, love, the fall of leaves in autumn.” Even Samuel Johnson maintained, “To circumscribe poetry by a definition will only show the narrowness of the definer.”

Poetry is a human fundamental, like music. It predates literacy and precedes prose in all literatures. There has probably never been a culture without it, yet no one knows precisely what it is. The word poesie entered the English language in the fourteenth century and begat poesy (as in Sidney’s “The Defence of Poesy,” ca. 1582) and posy , a motto in verse. Poetrie (from the Latin poetria) entered fourteenth-century English vocabulary and evolved into our poetry. The Greek word poiesis means “making.” The fact that the oldest term for the poet means “maker” suggests that a poem is constructed.

Poets (and others) have made many attempts over the centuries to account for poetry, an ancient and necessary instrument of our humanity:

Dante’s treatise on vernacular poetry, De vulgari eloquentia, suggests that around 1300, poetry was typically conceived of as a species of eloquence.

Sir Philip Sidney (1554–1586) said that poetry is “a representing, counterfetting, a figuring foorth: to speak metaphorically: a speaking picture: with this end, to teach and delight.”

Ben Jonson (1572–1637) referred to the art of poetry as “the craft of making.”

The baroque Jesuit poet Tomasso Ceva (1649–1737) said, “Poetry is a dream dreamed in the presence of reason.”

Coleridge (1772–1834) claimed that poetry equals “the best words in the best order.” He characterized it as “that synthetic and magical power, to which we have exclusively appropriated the name of imagination.”

Wordsworth (1771–1850) famously called poetry “the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings . . . recollected in tranquility.”

John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) followed up Wordsworth’s emphasis on overflowing emotion when he wrote that poetry is “feeling confessing itself to itself in moments of solitude.”

Shelley (1792–1822) joyfully called poetry “the record of the best and happiest moments of the happiest and best minds.” He said that poetry “redeems from decay the visitations of the divinity in man.”

Matthew Arnold (1822–1888) narrowed the definition to “a criticism of life.”

Ezra Pound (1885–1972) later countered, “Poetry is about as much a ‘criticism of life’ as red-hot iron is a criticism of fire.”

Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844–1889) characterized it as “speech framed . . . to be heard for its own sake and interest even over and above its interest of meaning.”

W. B. Yeats (1865–1939) loved Gavin Douglas’s 1553 definition of poetry as “pleasance and half wonder.”

George Santayana (1863–1952) said that “poetry is speech in which the instrument counts as well as the meaning.” But he also thought of it as something beyond “verbal expression,” as “that subtle fire and inward light which seems at times to shine through the world and to touch the images in our minds with ineffable beauty.”

Wallace Stevens (1879–1955) characterized poetry as “a revelation of words by means of the words.”

Tolstoy (1828–1910) noted in his diary, “Poetry is verse: prose is not verse. Or else poetry is everything with the exception of business documents and school books.” Years later, Marianne Moore (1887–1972) responded “[N]or is it valid / to discriminate against ‘business documents and // school books.’” Instead, she called poems “imaginary gardens with real toads in them.”

Gertrude Stein (1874–1946) decided, “Poetry is doing nothing but using losing refusing and pleasing and betraying and caressing nouns.”

Robert Frost (1874–1963) said wryly, “Poetry provides the one permissible way of saying one thing and meaning another.”

Robert Graves (1895–1985) thought of it as a form of “stored magic,” Andre Breton (1896–1966) as a “room of marvels.”

Howard Nemerov (1920–1991) said that poetry is simply “getting something right in language.”

Joseph Brodsky (1940–1996) described poetry as “accelerated thinking,” Seamus Heaney (1939–2013) called it “language in orbit.”

Poetry seems at core a verbal transaction. In its oral form, it establishes a relationship between a speaker and a listener; in its written form, it establishes a relationship between a writer and a reader. Yet at times that relationship seems to go beyond words. John Keats (1795–1821) felt that “Poetry should . . . strike the Reader as a wording of his own highest thoughts, and appear almost a Remembrance.” The Australian poet Les Murray (b. 1938) argues that “poetry exists to provide the poetic experience.” That experience is “a temporary possession.” We know it by contact, since it has an intensity that cannot be denied.

Emily Dickinson (1830–1886) wrote in an 1870 letter:

If I read a book [and] it makes my whole body so cold no fire can ever warm me I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only ways I know it. Is there any other way?

A. E. Housman wrote in The Name and Nature of Poetry (1933) :

A year or two ago, in common with others, I received from America a request that I would define poetry. I replied that I could no more define poetry than a terrier can define a rat, but that I thought we both recognized the object by the symptoms which it provokes in us. One of these symptoms was described in connection with another object by Eliphaz the Termanite: 'A spirit passed before my face: the hair of my flesh stood up.' Experience has taught me, when I am shaving of a morning, to keep watch over my thoughts, because, if a line of poetry strays into my memory, my skin bristles so that the razor ceases to act. This particular symptom is accompanied by a shiver down the spine; there is another which consists in a constriction of the throat and a precipitation of water in the eyes; and there is a third which I can only describe by borrowing a phrase from one of Keats’ last letters, where he says, speaking of Fanny Brawne, 'everything that reminds me of her goes through me like a spear.'

Read more from this collection .

Newsletter Sign Up

- Academy of American Poets Newsletter

- Academy of American Poets Educator Newsletter

- Teach This Poem

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

6.1: What is Poetry?

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 40422

- Heather Ringo & Athena Kashyap

- City College of San Francisco via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Image from Pixabay

What is Poetry?

Poetry is a condensed form of writing. As an art, it can effectively invoke a range of emotions in the reader. It can be presented in a number of forms — ranging from traditional rhymed poems such as sonnets to contemporary free verse. Poetry has always been intrinsically tied to music and many poems work with rhythm. It often brings awareness of current issues such as the state of the environment, but can also be read just for the sheer pleasure.

A poet makes the invisible visible. The invisible includes our deepest feelings and angsts, and also our joys, sorrows, and unanswered questions of being human. How is a poet able to do this? A poet uses fresh and original language , and is more interested in how the arrangement of words affects the reader rather than solely grammatical construction. The poet thinks about how words sound , the musicality within each word and also how the words come together.

Like fiction writers, poets mostly show rather than tell . They describe the scene vividly using as few words as possible and prefer to describe rather than analyze, leaving the latter to the people who read and write about poetry as you are doing in this class.

The Purpose of Poetry

If you’ve taken a composition or freshman writing course, you might recognize some familiar terms used above — summarizes, sources, persuades, ethos. These are all words you will rarely, if ever, use in reference to writing poetry. And why is that? Well, what’s the purpose of poetry? Perhaps this is not an easy question to answer. In fact, the answer might depend on time and culture. Epics such as Gilgamesh aided in memorization and preserved stories meant to be passed down orally. The British Romantics valued the pleasure derived from hearing and reading poetry. In some cultures poetry is important in ritual and religious practice. In contemporary times, many describe poetry as being a tool for self-expression.

In the excellent glossary in his book How to Read a Poem and Fall in Love with Poetry , poet Edward Hirsch provides the following definition for a poem:

Poem: A made thing, a verbal construct, an event in language. The word poesis means “making;” and the oldest term for the poet means “maker.” The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics points out that the medieval and Renaissance poets used the word makers , as in “courtly makers,” as a precise equivalent for poets. (Hence William Dunbar’s “Lament for the Makers.”) The word poem came into English in the sixteenth century and has been with us ever since to denote a form of fabrication, a verbal composition, a made thing.

William Carlos Williams defined the poem as “a small (or large) machine made of words.” (He added that there is nothing redundant about a machine.) Wallace Stevens characterized poetry as “a revelation of words by means of the words.” In his helpful essay “What is Poetry?” linguist Roman Jakobson declared:

“Poeticity is present when the word is felt as a word and not a mere representation of the object being named or an outburst of emotion, when words and their composition, their meaning, their external and internal form, acquire a weight and value of their own instead of referring indifferently to reality.”

Ben Johnson referred to the art of poetry as “the craft of making.” The old Irish word cerd, meaning “people of the craft,” was a designation for artisans, including poets. It is cognate with the Greek kerdos , meaning “craft, craftiness.” Two basic metaphors for the art of poetry in the classical world were carpentry and weaving. “Whatsoever else it may be,” W. H. Auden said, “a poem is a verbal artifact which must be as skillfully and solidly constructed as a table or a motorcycle.”

The true poem has been crafted into a living entity. It has magical potency, ineffable spirit. There is always something mysterious and inexplicable in a poem. It is an act—an action—beyond paraphrase because what is said is always inseparable from the way it is being said. A poem creates an experience in the reader that cannot be reduced to anything else. Perhaps it exists in order to create that aesthetic experience. Octavio Paz maintained that the poet and the reader are two moments of a single reality.

Of the many ideas provided here in this definition, perhaps the one to emphasize most is that the poem is “an event in language.” It is also one of the harder to understand concepts. “A poem creates an experience in the reader that cannot be reduced to anything else,” writes Hirsch. Especially not through paraphrase. This means that in order to “experience” a poem, a reader needs to read it as it is. The poem is itself a type of virtual reality.

Jeremy Arnold, a professor of philosophy at the University of Woolamaloo in Canada, likens the poem to the “pensieve” device in the Harry Potter series: “A poem allows someone to preserve a mental experience so that an outsider can access it as if it were their own.” When coming to poetry, there may be nothing more important to understand because nothing can shape your perspective more on how to write and for what purpose. Poetry requires a reader, an audience; therefore, the poet must learn how to best engage an audience. And this engagement doesn’t happen by sharing ideas, feelings, or experiences, by telling the reader about your experiences — it happens by creating them on the page with words that evoke the senses. With images . These, then, are how the literary genres speak. Images are their muscles. Their heart. Images are poetry’s body and soul.

Choose a poem from the Poetry Foundation’s featured poems and look again at Edward Hirsh’s definition of poem. How does this poem typify his explanation? Are there any ways in which it does not? Write a short response (300 words or less) explaining how you see your selected poem in relation to Hirsch’s definition.

Video: Billy Collins, A Poet, Speaks Out

Watch Billy Collins’ audio/visual poem:

Video 6.1.1 : Introduction to Poetry by Billy Collins

After watching the video above, read the poem here , and click on the link below to listen to a lecture by Billy Collins on his craft and how it relates to the reader.

Contributors and Attributions

Adapted from Naming the Unnameable: An Approach to Poetry for New Generations by Michelle Bonczek Evory, sourced from SUNY, CC-BY-NC-SA

What Is Poetry, and How Is It Different?

Goodshoped35110s/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY 4.0

- Favorite Poems & Poets

Poetic Forms

- Best Sellers

- Classic Literature

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/reading-in-mexico-56a1c0f23df78cf7726da4d7.jpg)

- B.A., English Education, University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill

There are as many definitions of poetry as there are poets. William Wordsworth defined poetry as "the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings." Emily Dickinson said, "If I read a book and it makes my body so cold no fire ever can warm me, I know that is poetry." Dylan Thomas defined poetry this way: "Poetry is what makes me laugh or cry or yawn, what makes my toenails twinkle, what makes me want to do this or that or nothing."

Poetry is a lot of things to a lot of people. Homer's epic, " The Odyssey ," described the wanderings of the adventurer, Odysseus, and has been called the greatest story ever told. During the English Renaissance, dramatic poets such as John Milton, Christopher Marlowe, and of course, William Shakespeare gave us enough words to fill textbooks, lecture halls, and universities. Poems from the Romantic period include Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's "Faust" (1808), Samuel Taylor Coleridge's "Kubla Khan" (1816), and John Keats' "Ode on a Grecian Urn" (1819).

Shall we go on? Because in order to do so, we would have to continue through 19th-century Japanese poetry, early Americans that include Emily Dickinson and T.S. Eliot, postmodernism, experimentalists, form versus free verse, slam, and so on.

What Defines Poetry?

Perhaps the characteristic most central to the definition of poetry is its unwillingness to be defined, labeled, or nailed down. Poetry is the chiseled marble of language. It is a paint-spattered canvas, but the poet uses words instead of paint, and the canvas is you. Poetic definitions of poetry kind of spiral in on themselves, however, like a dog eating itself from the tail up. Let's get nitty. Let's, in fact, get gritty. We can likely render an accessible definition of poetry by simply looking at its form and its purpose.

One of the most definable characteristics of the poetic form is the economy of language. Poets are miserly and unrelentingly critical in the way they dole out words. Carefully selecting words for conciseness and clarity is standard, even for writers of prose. However, poets go well beyond this, considering a word's emotive qualities, its backstory, its musical value, its double- or triple-entendres, and even its spatial relationship on the page. The poet, through innovation in both word choice and form, seemingly rends significance from thin air.

One may use prose to narrate, describe, argue, or define. There are equally numerous reasons for writing poetry . But poetry, unlike prose, often has an underlying and overarching purpose that goes beyond the literal. Poetry is evocative. It typically provokes in the reader an intense emotion: joy, sorrow, anger, catharsis, love, etc. Poetry has the ability to surprise the reader with an "Ah-ha!" experience and to give revelation, insight, and further understanding of elemental truth and beauty. Like Keats said: "Beauty is truth. Truth, beauty. That is all ye know on Earth and all ye need to know."

How's that? Do we have a definition yet? Let's sum it up like this: Poetry is artistically rendering words in such a way as to evoke intense emotion or an "ah-ha!" experience from the reader, being economical with language and often writing in a set form. Boiling it down like that doesn't quite satisfy all the nuances, the rich history, and the work that goes into selecting each word, phrase, metaphor, and punctuation mark to craft a written piece of poetry, but it's a start.

It's difficult to shackle poetry with definitions. Poetry is not old, frail, and cerebral. Poetry is stronger and fresher than you think. Poetry is imagination and will break those chains faster than you can say "Harlem Renaissance."

To borrow a phrase, poetry is a riddle wrapped in an enigma swathed in a cardigan sweater... or something like that. An ever-evolving genre, it will shirk definitions at every turn. That continual evolution keeps it alive. Its inherent challenges to doing it well and its ability to get at the core of emotion or learning keep people writing it. The writers are just the first ones to have the ah-ha moments as they're putting the words on the page (and revising them).

Rhythm and Rhyme

If poetry as a genre defies easy description, we can at least look at labels of different kinds of forms. Writing in form doesn't just mean that you need to pick the right words but that you need to have correct rhythm (prescribed stressed and unstressed syllables), follow a rhyming scheme (alternate lines rhyme or consecutive lines rhyme), or use a refrain or repeated line.

Rhythm. You may have heard about writing in iambic pentameter , but don't be intimidated by the jargon. Iambic just means that there is an unstressed syllable that comes before a stressed one. It has a "clip-clop," horse gallop feel. One stressed and one unstressed syllable makes one "foot," of the rhythm, or meter, and five in a row makes up pentameter . For example, look at this line from Shakespeare's "Romeo & Juliet," which has the stressed syllables bolded: "But, soft ! What light through yon der win dow breaks ?" Shakespeare was a master at iambic pentameter.

Rhyme scheme. Many set forms follow a particular pattern to their rhyming. When analyzing a rhyme scheme, lines are labeled with letters to note what ending of each rhymes with which other. Take this stanza from Edgar Allen Poe 's ballad "Annabel Lee:"

It was many and many a year ago, In a kingdom by the sea, That a maiden there lived whom you may know By the name of Annabel Lee; And this maiden she lived with no other thought Than to love and be loved by me.

The first and third lines rhyme, and the second, fourth, and sixth lines rhyme, which means it has an a-b-a-b-c-b rhyme scheme, as "thought" does not rhyme with any of the other lines. When lines rhyme and they're next to each other, they're called a rhyming couplet . Three in a row is called a rhyming triplet . This example does not have a rhyming couplet or triplet because the rhymes are on alternating lines.

Even young schoolchildren are familiar with poetry such as the ballad form (alternating rhyme scheme), the haiku (three lines made up of five syllables, seven syllables, and five syllables), and even the limerick — yes, that's a poetic form in that it has a rhythm and rhyme scheme. It might not be literary, but it is poetry.

Blank verse poems are written in an iambic format, but they don't carry a rhyme scheme. If you want to try your hand at challenging, complex forms, those include the sonnet (Shakespeare's bread and butter), villanelle (such as Dylan Thomas's "Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night."), and sestina , which rotates line-ending words in a specific pattern among its six stanzas. For terza rima, check out translations of Dante Alighieri's "The Divine Comedy," which follows this rhyme scheme: aba, bcb, cdc, ded in iambic pentameter.

Free verse doesn't have any rhythm or rhyme scheme, though its words still need to be written economically. Words that start and end lines still have particular weight, even if they don't rhyme or have to follow any particular metering pattern.

The more poetry you read, the better you'll be able to internalize the form and invent within it. When the form seems second nature, then the words will flow from your imagination to fill it more effectively than when you're first learning the form.

Masters in Their Field

The list of masterful poets is long. To find what kinds you like, read a wide variety of poetry, including those already mentioned here. Include poets from around the world and all through time, from the "Tao Te Ching" to Robert Bly and his translations (Pablo Neruda, Rumi, and many others). Read Langston Hughes to Robert Frost. Walt Whitman to Maya Angelou. Sappho to Oscar Wilde. The list goes on and on. With poets of all nationalities and backgrounds putting out work today, your study never really has to end, especially when you find someone's work that sends electricity up your spine.

Flanagan, Mark. "What is Poetry?" Run Spot Run, April 25, 2015.

Grein, Dusty. "How to Write a Sestina (with Examples and Diagrams)." The Society of Classical Poets, December 14, 2016.

Shakespeare, William. "Romeo and Juliet." Paperback, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, June 25, 2015.

- What Is a Sonnet?

- An Introduction to Blank Verse

- What Is an Iamb in Poetry?

- An Introduction to Iambic Pentameter

- An Introduction to Free Verse Poetry

- The Stanza: The Poem Within The Poem

- Heroic Couplets: What They Are and What They Do

- What Is Enjambment? Definition and Examples

- How to Identify and Understand Masculine Rhyme in Poetry

- Examples of Iambic Pentameter in Shakespeare's Plays

- The Sonnet: A Poem in 14 Lines

- Spondee: Definition and Examples from Poetry

- Overview of Imagism in Poetry

- What Is Narrative Poetry? Definition and Examples

- 5 Ways to Celebrate National Poetry Month in the Classroom

- Singing the Old Songs: Traditional and Literary Ballads

Finding Meaning in Poetry

by Melissa Donovan | Jan 12, 2023 | Poetry Writing | 18 comments

Finding meaning in poetry.

We humans are programmed to find meaning in everything. We find patterns where none exist . We look for hidden messages in works of art . We yearn for meaning, especially when something doesn’t immediately make sense.

Of course, art is open to interpretation, and some of the best works of art have produced a fountain of ideas about what they mean. From the nonsensical children’s story Alice in Wonderland to the complex historical fantasy series A Song of Ice and Fire (aff links), we wonder what a story means — what it’s really about, at its core.

Finding Meaning in Abstract Poetry

The literary canon is home to countless poems with abstract meaning. One of my favorites is “ anyone lived in a pretty how town ” by E.E. Cummings. Here’s an excerpt:

anyone lived in a pretty how town (with up so floating many bells down) spring summer autumn winter he sang his didn’t he danced his did.

Whenever I read this poem, I see a lot of imagery: bells; the changing of the seasons; people; the sun, stars, and moon. Phrases like “up so floating many bells down” are enigmatic. Cummings takes great liberty with grammar and punctuation, using all lowercase letters and eliminating spaces in some lines, which intensifies the poem’s ambiguity.

But what does it all mean? I can’t be sure. This uncertainty imbibes the poem with a sense of wonder. Each time I read it, the meaning changes ever so slightly. It’s almost an ethereal experience to revisit the poem every couple of years to see what it will be like this time.

Maybe Cummings had a particular idea in mind when he wrote this poem, or maybe he wasn’t sure what he was trying to say. Maybe the poem has no meaning and it’s just a nonsensical romp through language and imagery. I don’t think any of that matters. What matters is the act of Cummings writing the poem and the experience we get from reading it. With a poem like this, each reader will have a different experience. That’s quite a gift — one poem that can mean different things to different people.

Vague Meaning in Poetry