Quoting, Summarizing, and Paraphrasing a Source Part 1: Summarizing Review the following passage and summarize it in the box as though you were including this information in a research paper. Use the reference to create an appropriate APA-formatted, in-text citation.

Jiskha Homework Help is now Questions LLC.

Since 1998, Jiskha Homework Help has assisted students by providing helpful responses to homework questions in a variety of school subjects.

The time has come for us to rename our website and expand our mission.

Therefore, beginning July 15, 2022, Jiskha Homework Help began renaming its website to Questions LLC , and existing data is gradually being moved to our new domain name. We hope to complete the move by July 31, 2022.

We can help more people.

In addition to school subjects like math, science, history, and geography, Questions LLC will provide helpful answers in virtually every category imaginable.

For example, new categories may include:

- Arts & Performance

- Computer Technology

- Finance & Investing

- Health & Fitness

- Personal Interests

and many others.

We can provide a better experience.

By adding more categories, we can reach a broader audience and help more people. This will also enable us to improve our software much more efficiently, resulting in a better and more useful experience for all visitors.

For example, in addition to maintaining our website in its current form, we plan to:

- Further integrate user accounts with improved features and functionality.

- Drastically enhance navigation and search capabilities.

- Build a mobile app to supplement our existing website.

- Use algorithms and A.I. to continuously perform automated tasks.

Get helpful answers, not just the right answers.

Questions LLC will continue to encourage visitors to:

- Ask interesting and relevant questions with pertinent details attached.

- Provide helpful answers to questions rather than just the right answers.

We want to give a huge Thank You to all of the visitors who have used Jiskha Homework Help over the last two decades. We're extremely grateful that you've used our website.

This upcoming move will help us better serve a larger community and implement many of the specific features our users have been asking for. We hope you’ll join us during the next phase of our journey as we transition to our new name and expanded mission.

As always, please feel free to contact us if you have any questions, comments, or feedback.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Quoting, Paraphrasing, and Summarizing

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

This handout is intended to help you become more comfortable with the uses of and distinctions among quotations, paraphrases, and summaries. This handout compares and contrasts the three terms, gives some pointers, and includes a short excerpt that you can use to practice these skills.

What are the differences among quoting, paraphrasing, and summarizing?

These three ways of incorporating other writers' work into your own writing differ according to the closeness of your writing to the source writing.

Quotations must be identical to the original, using a narrow segment of the source. They must match the source document word for word and must be attributed to the original author.

Paraphrasing involves putting a passage from source material into your own words. A paraphrase must also be attributed to the original source. Paraphrased material is usually shorter than the original passage, taking a somewhat broader segment of the source and condensing it slightly.

Summarizing involves putting the main idea(s) into your own words, including only the main point(s). Once again, it is necessary to attribute summarized ideas to the original source. Summaries are significantly shorter than the original and take a broad overview of the source material.

Why use quotations, paraphrases, and summaries?

Quotations, paraphrases, and summaries serve many purposes. You might use them to:

- Provide support for claims or add credibility to your writing

- Refer to work that leads up to the work you are now doing

- Give examples of several points of view on a subject

- Call attention to a position that you wish to agree or disagree with

- Highlight a particularly striking phrase, sentence, or passage by quoting the original

- Distance yourself from the original by quoting it in order to cue readers that the words are not your own

- Expand the breadth or depth of your writing

Writers frequently intertwine summaries, paraphrases, and quotations. As part of a summary of an article, a chapter, or a book, a writer might include paraphrases of various key points blended with quotations of striking or suggestive phrases as in the following example:

In his famous and influential work The Interpretation of Dreams , Sigmund Freud argues that dreams are the "royal road to the unconscious" (page #), expressing in coded imagery the dreamer's unfulfilled wishes through a process known as the "dream-work" (page #). According to Freud, actual but unacceptable desires are censored internally and subjected to coding through layers of condensation and displacement before emerging in a kind of rebus puzzle in the dream itself (page #).

How to use quotations, paraphrases, and summaries

Practice summarizing the essay found here , using paraphrases and quotations as you go. It might be helpful to follow these steps:

- Read the entire text, noting the key points and main ideas.

- Summarize in your own words what the single main idea of the essay is.

- Paraphrase important supporting points that come up in the essay.

- Consider any words, phrases, or brief passages that you believe should be quoted directly.

There are several ways to integrate quotations into your text. Often, a short quotation works well when integrated into a sentence. Longer quotations can stand alone. Remember that quoting should be done only sparingly; be sure that you have a good reason to include a direct quotation when you decide to do so. You'll find guidelines for citing sources and punctuating citations at our documentation guide pages.

Quoting and Paraphrasing

Download this Handout PDF

College writing often involves integrating information from published sources into your own writing in order to add credibility and authority–this process is essential to research and the production of new knowledge.

However, when building on the work of others, you need to be careful not to plagiarize : “to steal and pass off (the ideas and words of another) as one’s own” or to “present as new and original an idea or product derived from an existing source.”1 The University of Wisconsin–Madison takes this act of “intellectual burglary” very seriously and considers it to be a breach of academic integrity . Penalties are severe.

These materials will help you avoid plagiarism by teaching you how to properly integrate information from published sources into your own writing.

1. Merriam Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 10th ed. (Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster, 1993), 888.

How to avoid plagiarism

When using sources in your papers, you can avoid plagiarism by knowing what must be documented.

Specific words and phrases

If you use an author’s specific word or words, you must place those words within quotation marks and you must credit the source.

Information and Ideas

Even if you use your own words, if you obtained the information or ideas you are presenting from a source, you must document the source.

Information : If a piece of information isn’t common knowledge (see below), you need to provide a source.

Ideas : An author’s ideas may include not only points made and conclusions drawn, but, for instance, a specific method or theory, the arrangement of material, or a list of steps in a process or characteristics of a medical condition. If a source provided any of these, you need to acknowledge the source.

Common Knowledge?

You do not need to cite a source for material considered common knowledge:

General common knowledge is factual information considered to be in the public domain, such as birth and death dates of well-known figures, and generally accepted dates of military, political, literary, and other historical events. In general, factual information contained in multiple standard reference works can usually be considered to be in the public domain.

Field-specific common knowledge is “common” only within a particular field or specialty. It may include facts, theories, or methods that are familiar to readers within that discipline. For instance, you may not need to cite a reference to Piaget’s developmental stages in a paper for an education class or give a source for your description of a commonly used method in a biology report—but you must be sure that this information is so widely known within that field that it will be shared by your readers.

If in doubt, be cautious and cite the source. And in the case of both general and field-specific common knowledge, if you use the exact words of the reference source, you must use quotation marks and credit the source.

Paraphrasing vs. Quoting — Explanation

Should i paraphrase or quote.

In general, use direct quotations only if you have a good reason. Most of your paper should be in your own words. Also, it’s often conventional to quote more extensively from sources when you’re writing a humanities paper, and to summarize from sources when you’re writing in the social or natural sciences–but there are always exceptions.

In a literary analysis paper , for example, you”ll want to quote from the literary text rather than summarize, because part of your task in this kind of paper is to analyze the specific words and phrases an author uses.

In research papers , you should quote from a source

- to show that an authority supports your point

- to present a position or argument to critique or comment on

- to include especially moving or historically significant language

- to present a particularly well-stated passage whose meaning would be lost or changed if paraphrased or summarized

You should summarize or paraphrase when

- what you want from the source is the idea expressed, and not the specific language used to express it

- you can express in fewer words what the key point of a source is

How to paraphrase a source

General advice.

- When reading a passage, try first to understand it as a whole, rather than pausing to write down specific ideas or phrases.

- Be selective. Unless your assignment is to do a formal or “literal” paraphrase, you usually don?t need to paraphrase an entire passage; instead, choose and summarize the material that helps you make a point in your paper.

- Think of what “your own words” would be if you were telling someone who’s unfamiliar with your subject (your mother, your brother, a friend) what the original source said.

- Remember that you can use direct quotations of phrases from the original within your paraphrase, and that you don’t need to change or put quotation marks around shared language.

Methods of Paraphrasing

- Look away from the source then write. Read the text you want to paraphrase several times until you feel that you understand it and can use your own words to restate it to someone else. Then, look away from the original and rewrite the text in your own words.

- Take notes. Take abbreviated notes; set the notes aside; then paraphrase from the notes a day or so later, or when you draft.

If you find that you can’t do A or B, this may mean that you don’t understand the passage completely or that you need to use a more structured process until you have more experience in paraphrasing.

The method below is not only a way to create a paraphrase but also a way to understand a difficult text.

Paraphrasing difficult texts

Consider the following passage from Love and Toil (a book on motherhood in London from 1870 to 1918), in which the author, Ellen Ross, puts forth one of her major arguments:

- Love and Toil maintains that family survival was the mother’s main charge among the large majority of London?s population who were poor or working class; the emotional and intellectual nurture of her child or children and even their actual comfort were forced into the background. To mother was to work for and organize household subsistence. (p. 9)

Children of the poor at the turn of the century received little if any emotional or intellectual nurturing from their mothers, whose main charge was family survival. Working for and organizing household subsistence were what defined mothering. Next to this, even the children’s basic comfort was forced into the background (Ross, 1995).

According to Ross (1993), poor children at the turn of the century received little mothering in our sense of the term. Mothering was defined by economic status, and among the poor, a mother’s foremost responsibility was not to stimulate her children’s minds or foster their emotional growth but to provide food and shelter to meet the basic requirements for physical survival. Given the magnitude of this task, children were deprived of even the “actual comfort” (p. 9) we expect mothers to provide today.

You may need to go through this process several times to create a satisfactory paraphrase.

Successful vs. unsuccessful paraphrases

Paraphrasing is often defined as putting a passage from an author into “your own words.” But what are your own words? How different must your paraphrase be from the original?

The paragraphs below provide an example by showing a passage as it appears in the source, two paraphrases that follow the source too closely, and a legitimate paraphrase.

The student’s intention was to incorporate the material in the original passage into a section of a paper on the concept of “experts” that compared the functions of experts and nonexperts in several professions.

The Passage as It Appears in the Source

Critical care nurses function in a hierarchy of roles. In this open heart surgery unit, the nurse manager hires and fires the nursing personnel. The nurse manager does not directly care for patients but follows the progress of unusual or long-term patients. On each shift a nurse assumes the role of resource nurse. This person oversees the hour-by-hour functioning of the unit as a whole, such as considering expected admissions and discharges of patients, ascertaining that beds are available for patients in the operating room, and covering sick calls. Resource nurses also take a patient assignment. They are the most experienced of all the staff nurses. The nurse clinician has a separate job description and provides for quality of care by orienting new staff, developing unit policies, and providing direct support where needed, such as assisting in emergency situations. The clinical nurse specialist in this unit is mostly involved with formal teaching in orienting new staff. The nurse manager, nurse clinician, and clinical nurse specialist are the designated experts. They do not take patient assignments. The resource nurse is seen as both a caregiver and a resource to other caregivers. . . . Staff nurses have a hierarchy of seniority. . . . Staff nurses are assigned to patients to provide all their nursing care. (Chase, 1995, p. 156)

Word-for-Word Plagiarism

Critical care nurses have a hierarchy of roles. The nurse manager hires and fires nurses. S/he does not directly care for patients but does follow unusual or long-term cases. On each shift a resource nurse attends to the functioning of the unit as a whole, such as making sure beds are available in the operating room , and also has a patient assignment . The nurse clinician orients new staff, develops policies, and provides support where needed . The clinical nurse specialist also orients new staff, mostly by formal teaching. The nurse manager, nurse clinician, and clinical nurse specialist , as the designated experts, do not take patient assignments . The resource nurse is not only a caregiver but a resource to the other caregivers . Within the staff nurses there is also a hierarchy of seniority . Their job is to give assigned patients all their nursing care .

Why this is plagiarism

Notice that the writer has not only “borrowed” Chase’s material (the results of her research) with no acknowledgment, but has also largely maintained the author’s method of expression and sentence structure. The phrases in red are directly copied from the source or changed only slightly in form.

Even if the student-writer had acknowledged Chase as the source of the content, the language of the passage would be considered plagiarized because no quotation marks indicate the phrases that come directly from Chase. And if quotation marks did appear around all these phrases, this paragraph would be so cluttered that it would be unreadable.

A Patchwork Paraphrase

Chase (1995) describes how nurses in a critical care unit function in a hierarchy that places designated experts at the top and the least senior staff nurses at the bottom. The experts — the nurse manager, nurse clinician, and clinical nurse specialist — are not involved directly in patient care. The staff nurses, in contrast, are assigned to patients and provide all their nursing care . Within the staff nurses is a hierarchy of seniority in which the most senior can become resource nurses: they are assigned a patient but also serve as a resource to other caregivers. The experts have administrative and teaching tasks such as selecting and orienting new staff, developing unit policies , and giving hands-on support where needed.

This paraphrase is a patchwork composed of pieces in the original author’s language (in red) and pieces in the student-writer’s words, all rearranged into a new pattern, but with none of the borrowed pieces in quotation marks. Thus, even though the writer acknowledges the source of the material, the underlined phrases are falsely presented as the student’s own.

A Legitimate Paraphrase

In her study of the roles of nurses in a critical care unit, Chase (1995) also found a hierarchy that distinguished the roles of experts and others. Just as the educational experts described above do not directly teach students, the experts in this unit do not directly attend to patients. That is the role of the staff nurses, who, like teachers, have their own “hierarchy of seniority” (p. 156). The roles of the experts include employing unit nurses and overseeing the care of special patients (nurse manager), teaching and otherwise integrating new personnel into the unit (clinical nurse specialist and nurse clinician), and policy-making (nurse clinician). In an intermediate position in the hierarchy is the resource nurse, a staff nurse with more experience than the others, who assumes direct care of patients as the other staff nurses do, but also takes on tasks to ensure the smooth operation of the entire facility.

Why this is a good paraphrase

The writer has documented Chase’s material and specific language (by direct reference to the author and by quotation marks around language taken directly from the source). Notice too that the writer has modified Chase’s language and structure and has added material to fit the new context and purpose — to present the distinctive functions of experts and nonexperts in several professions.

Shared Language

Perhaps you’ve noticed that a number of phrases from the original passage appear in the legitimate paraphrase: critical care, staff nurses, nurse manager, clinical nurse specialist, nurse clinician, resource nurse.

If all these phrases were in red, the paraphrase would look much like the “patchwork” example. The difference is that the phrases in the legitimate paraphrase are all precise, economical, and conventional designations that are part of the shared language within the nursing discipline (in the too-close paraphrases, they’re red only when used within a longer borrowed phrase).

In every discipline and in certain genres (such as the empirical research report), some phrases are so specialized or conventional that you can’t paraphrase them except by wordy and awkward circumlocutions that would be less familiar (and thus less readable) to the audience.

When you repeat such phrases, you’re not stealing the unique phrasing of an individual writer but using a common vocabulary shared by a community of scholars.

Some Examples of Shared Language You Don’t Need to Put in Quotation Marks

- Conventional designations: e.g., physician’s assistant, chronic low-back pain

- Preferred bias-free language: e.g., persons with disabilities

- Technical terms and phrases of a discipline or genre : e.g., reduplication, cognitive domain, material culture, sexual harassment

Chase, S. K. (1995). The social context of critical care clinical judgment. Heart and Lung, 24, 154-162.

How to Quote a Source

Introducing a quotation.

One of your jobs as a writer is to guide your reader through your text. Don’t simply drop quotations into your paper and leave it to the reader to make connections.

Integrating a quotation into your text usually involves two elements:

- A signal that a quotation is coming–generally the author’s name and/or a reference to the work

- An assertion that indicates the relationship of the quotation to your text

Often both the signal and the assertion appear in a single introductory statement, as in the example below. Notice how a transitional phrase also serves to connect the quotation smoothly to the introductory statement.

Ross (1993), in her study of poor and working-class mothers in London from 1870-1918 [signal], makes it clear that economic status to a large extent determined the meaning of motherhood [assertion]. Among this population [connection], “To mother was to work for and organize household subsistence” (p. 9).

The signal can also come after the assertion, again with a connecting word or phrase:

Illness was rarely a routine matter in the nineteenth century [assertion]. As [connection] Ross observes [signal], “Maternal thinking about children’s health revolved around the possibility of a child’s maiming or death” (p. 166).

Formatting Quotations

Short direct prose.

Incorporate short direct prose quotations into the text of your paper and enclose them in double quotation marks:

According to Jonathan Clarke, “Professional diplomats often say that trying to think diplomatically about foreign policy is a waste of time.”

Longer prose quotations

Begin longer quotations (for instance, in the APA system, 40 words or more) on a new line and indent the entire quotation (i.e., put in block form), with no quotation marks at beginning or end, as in the quoted passage from our Successful vs. Unsucessful Paraphrases page.

Rules about the minimum length of block quotations, how many spaces to indent, and whether to single- or double-space extended quotations vary with different documentation systems; check the guidelines for the system you’re using.

Quotation of Up to 3 Lines of Poetry

Quotations of up to 3 lines of poetry should be integrated into your sentence. For example:

In Julius Caesar, Antony begins his famous speech with “Friends, Romans, Countrymen, lend me your ears; / I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him” (III.ii.75-76).

Notice that a slash (/) with a space on either side is used to separate lines.

Quotation of More than 3 Lines of Poetry

More than 3 lines of poetry should be indented. As with any extended (indented) quotation, do not use quotation marks unless you need to indicate a quotation within your quotation.

Punctuating with Quotation Marks

Parenthetical citations.

With short quotations, place citations outside of closing quotation marks, followed by sentence punctuation (period, question mark, comma, semi-colon, colon):

Menand (2002) characterizes language as “a social weapon” (p. 115).

With block quotations, check the guidelines for the documentation system you are using.

Commas and periods

Place inside closing quotation marks when no parenthetical citation follows:

Hertzberg (2002) notes that “treating the Constitution as imperfect is not new,” but because of Dahl’s credentials, his “apostasy merits attention” (p. 85).

Semicolons and colons

Place outside of closing quotation marks (or after a parenthetical citation).

Question marks and exclamation points

Place inside closing quotation marks if the quotation is a question/exclamation:

Menand (2001) acknowledges that H. W. Fowler’s Modern English Usage is “a classic of the language,” but he asks, “Is it a dead classic?” (p. 114).

[Note that a period still follows the closing parenthesis.]

Place outside of closing quotation marks if the entire sentence containing the quotation is a question or exclamation:

How many students actually read the guide to find out what is meant by “academic misconduct”?

Quotation within a quotation

Use single quotation marks for the embedded quotation:

According to Hertzberg (2002), Dahl gives the U. S. Constitution “bad marks in ‘democratic fairness’ and ‘encouraging consensus'” (p. 90).

[The phrases “democratic fairness” and “encouraging consensus” are already in quotation marks in Dahl’s sentence.]

Indicating Changes in Quotations

Quoting only a portion of the whole.

Use ellipsis points (. . .) to indicate an omission within a quotation–but not at the beginning or end unless it’s not obvious that you’re quoting only a portion of the whole.

Adding Clarification, Comment, or Correction

Within quotations, use square brackets [ ] (not parentheses) to add your own clarification, comment, or correction.

Use [sic] (meaning “so” or “thus”) to indicate that a mistake is in the source you’re quoting and is not your own.

Additional information

Information on summarizing and paraphrasing sources.

American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (4th ed.). (2000). Retrieved January 7, 2002, from http://www.bartleby.com/61/ Bazerman, C. (1995). The informed writer: Using sources in the disciplines (5th ed). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Leki, I. (1995). Academic writing: Exploring processes and strategies (2nd ed.) New York: St. Martin?s Press, pp. 185-211.

Leki describes the basic method presented in C, pp. 4-5.

Spatt, B. (1999). Writing from sources (5th ed.) New York: St. Martin?s Press, pp. 98-119; 364-371.

Information about specific documentation systems

The Writing Center has handouts explaining how to use many of the standard documentation systems. You may look at our general Web page on Documentation Systems, or you may check out any of the following specific Web pages.

If you’re not sure which documentation system to use, ask the course instructor who assigned your paper.

- American Psychological Assoicaion (APA)

- Modern Language Association (MLA)

- Chicago/Turabian (A Footnote or Endnote System)

- American Political Science Association (APSA)

- Council of Science Editors (CBE)

- Numbered References

You may also consult the following guides:

- American Medical Association, Manual for Authors and Editors

- Council of Science Editors, CBE style Manual

- The Chicago Manual of Style

- MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers

- Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association

Academic and Professional Writing

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Analysis Papers

Reading Poetry

A Short Guide to Close Reading for Literary Analysis

Using Literary Quotations

Play Reviews

Writing a Rhetorical Précis to Analyze Nonfiction Texts

Incorporating Interview Data

Grant Proposals

Planning and Writing a Grant Proposal: The Basics

Additional Resources for Grants and Proposal Writing

Job Materials and Application Essays

Writing Personal Statements for Ph.D. Programs

- Before you begin: useful tips for writing your essay

- Guided brainstorming exercises

- Get more help with your essay

- Frequently Asked Questions

Resume Writing Tips

CV Writing Tips

Cover Letters

Business Letters

Proposals and Dissertations

Resources for Proposal Writers

Resources for Dissertators

Research Papers

Planning and Writing Research Papers

Writing Annotated Bibliographies

Creating Poster Presentations

Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper

Thank-You Notes

Advice for Students Writing Thank-You Notes to Donors

Reading for a Review

Critical Reviews

Writing a Review of Literature

Scientific Reports

Scientific Report Format

Sample Lab Assignment

Writing for the Web

Writing an Effective Blog Post

Writing for Social Media: A Guide for Academics

- AI in action

- AI in the enterprise

- Humans of AI

Words at work

- Inside Writer

- Content strategy

- Inspiration

– 10 min read

A detailed guide to quoting

Jessica Malnik

Quotations have the power to elevate your written work when used correctly. But in order to use a quote properly, you must give full credit to the original source.

Before you can learn how to properly include quoted material, you need to have a firm understanding of what a quotation is, the purpose for using one, and the difference between quoting and paraphrasing.

What is a quotation in writing?

Quotations serve multiple purposes in writing. Students and professionals alike can benefit from using quotations in their work. Whether you’re writing a research paper or a blog article, you’ll likely find yourself needing to use them at some point. Quoting can add perspective, validation, and evidence to your piece.

What do you mean by quoting?

Quoting is a technique that allows you to include an original passage from a source in your work as a direct quote. You do this by framing or surrounding the quote in quotation marks like this, “This is an example of a sentence framed by quotation marks.”

However, you can’t just add quotation marks and call it a day. You also need proper attribution for your source.

Keep in mind that there is a difference between direct quoting and indirect quoting. With direct quoting, you include the source’s exact words framed within quotation marks.

With indirect quoting, you can paraphrase what the person or text said in your own words instead of copying it verbatim. Indirect quoting, also known as indirect speech or discourse, is mostly used to summarize what someone said in a talk or interview. Indirect quotations are never placed within quotation marks.

How do you properly quote?

To properly quote someone, you’ll need to follow some general quoting rules along with properly citing your source using your preferred MLA, APA, or Chicago style guide.

For example, many people incorrectly use punctuation with quotation marks. Do you know whether or not to include punctuation inside the quotation marks?

Here’s how to handle punctuation marks with quotes, as well as a few more rules to consider when including quotations in your work:

Punctuation

As a good rule of thumb, periods and commas should go inside quotation marks. On the other hand, colons, semicolons, and dashes go outside of the quotation marks.

However, exclamation points and question marks aren’t set in stone. While these tend to go on the inside of quotation marks, in some instances, you might place them outside of the marks.

Here are a few examples to illustrate how this would work in practice:

“ You should keep commas inside the quotation marks, ” he explained.

She wanted to help, so she said, “ I’m happy to explain it ” ; they needed a thorough explanation, and she loved to teach her students.

It gets a little trickier with exclamation marks and question marks when quoting. These can be either inside the quotation marks or outside of them, depending on the situation. Keep question and exclamation marks inside the quotations if they apply to the quoted passage. If they apply to your sentence instead of the quote, you’ll want to keep them outside. Here’s an example:

He asked the students, “ Do you know how to use quotation marks? ”

Did the students hear the teacher when he said, “ I will show you how to use quotation marks ”?

Closing quotations

Once you start using a quotation mark, you have to close it. This means that you can’t leave a quote open like the example below because the reader wouldn’t know when the quote is over.

Capitalization

The rule of capitalization changes depending on the context.

For example, if you quote a complete sentence, then you should capitalize the first word in the sentence. However, if you are quoting a piece of a sentence or phrase, then you wouldn’t need to start with capitalization, like this:

She said, “ Here’s an example of a sentence that should start with a capital letter. ”

He said it was “ a good example of a sentence where capitalization isn’t necessary. ”

Sometimes, you’ll want to split a quote. You don’t need to capitalize the second half of the quote that’s divided by a parenthetical. Here’s an example to show you what that would look like:

“ Here is an example of a quote, ” she told her students, “ that doesn’t need capitalization in the second part . ”

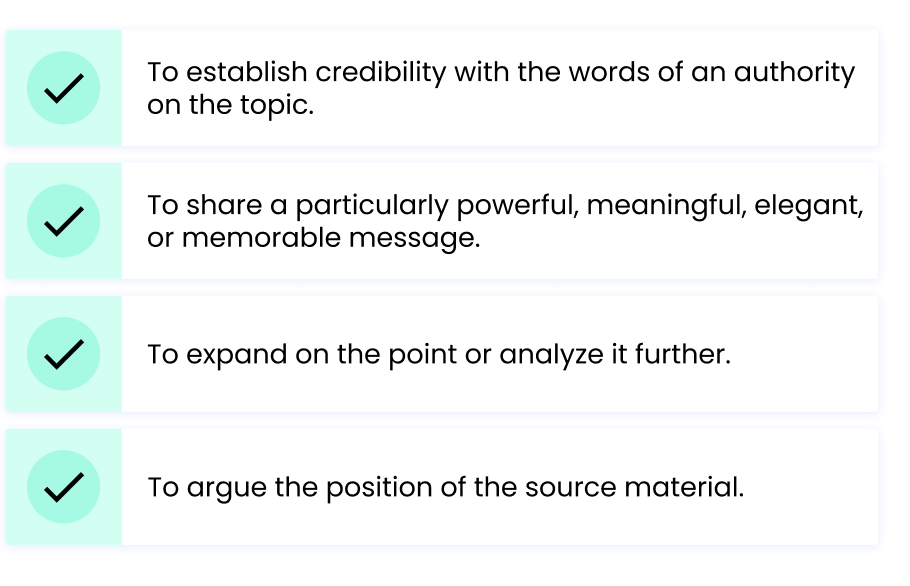

What is the purpose of quoting?

As stated above, quotations can serve multiple purposes in a written piece. Quotes can signify direct passages or titles of works. Here are a few of the reasons to include a quote within your written work:

These intentions can apply whether you’ve interviewed your source or are taking a quote from an existing, published piece.

However, before you use a quote, you’ll want to understand how it can strengthen your work and when you should use one. We’ll discuss when you should use quotes and how to properly cite them using different style guides in the next section.

When you should use quotes

Quotations should be used strategically, no matter what type of writing you’re doing. For instance, if you’re a professional copywriter crafting a white paper or a student writing a research paper, you’ll likely want to include as much proof as possible in your work. However, stuffing your paper with a ton of quotations can do more harm than good because the piece needs to represent your ideas and interpretations of the source, not just good quotes.

That being said, quoting reputable sources in your work is an excellent way to prove your points and add credibility to the piece. Use quotations in your work when you want to share accurate ideas and passages from source materials.

You should also use quotes when you want to add emphasis to a source on the topic you’re covering.

For example, if you’re writing a research paper, then it would be beneficial to add quotes from a professor involved in the study you’re referring to in your piece.

How to cite a quote in MLA, APA, and Chicago

MLA, APA, and Chicago are three of the most common citation styles. It’s a standardized way of crediting the sources that you quote. Depending on your assignment, you may need to use a specific one when citing your sources.

This section shares how to cite your quotes in these three popular citation styles, along with several examples of each.

Modern Language Association (MLA) is most often associated with academics in English or philosophic fields. With this style of citation, you’ll need to include quotes word-for-word. It’s fine to use only phrases or pieces from a specific quote, but you’ll need to keep the spelling and punctuation the same.

Here are some other criteria to keep in mind when citing using MLA style:

• If the quote goes longer than four lines, you must use a blockquote. Do not indent at the start of the quote block.

• Start quotes on the next line, ½ inch from the left margin of the paper.

• Quotes must be double spaced like the rest of the paper.

• Only use quotations when quotation marks are a part of the source.

• Include in-text citations next to the blockquote.

• If a blockquote is longer than a paragraph, you must start the next paragraph with the same indent.

• Don’t include a number in the parenthetical quotation if the source doesn’t use page numbers.

Here’s an example of a short, direct quote with MLA using a website resource without page numbers:

She always wanted to be a writer. “ I knew from a young age that I wanted to write a novel . ” (Smith)

And an example of a blockquote from page 2 of the source:

John Doe shares his experience getting his book published in the prologue:

I never expected so many people to be willing to help me publish this book. I had a lot of support along the way. My friends and colleagues always encouraged me to keep going. Some helped me edit, and others reminded me why I started in the first place. One of my good friends even brought me dinner when she knew I was going to be working late. (2)

With MLA, the reader can reference the full sources at the end in the Work Cited section. For this example, it could look like this:

Works Cited

Smith, J. (2021). Example Blog Post. Retrieved 2021, from www.example.com

Doe, J. (2021). Book Title One (1st ed., Vol. 1). Example, TX: Example Publishing.

See this article for more information on MLA style citations.

American Psychological Association (APA) is used often in psychology, education, and criminal justice fields. It often requires a cover page and abstract.

Here are a few points to consider when using APA style to cite your sources:

• Citation pages should be double spaced.

• All citations in a paper must have a full reference in the reference list.

• All references must have a hanging indent.

• Sources must be listed in alphabetical order, typically by the last name.

Using the same source examples as we did with MLA above, here is how they would be cited in APA:

Doe, Jane. Example Blog Post . 2021, www.example.com.

Doe, John. Book Title One . 1st ed., vol. 1, Example Publishing, 2021.

See this article for more information on APA style citations.

Chicago Manual of Style (CMS) is commonly used in history and humanities fields. It was created to help researchers. Here are a few points to keep in mind for Chicago Style:

• There are 2 types of referencing styles:

→ Notes and Bibliography

→ Author-Date

• The list of bibliography must be single-spaced.

• The text should be double spaced, except for block quotations, tables, notes, and bibliographies.

• The second line should be indented for sources.

•Author last names must be arranged alphabetically.

Here’s how the same example sources used above would be cited using Chicago style:

Doe, Jane. “Example Blog Post,” 2021. www.example.com.

Doe, John. Book Title One . 1. 1st ed. Vol. 1. Example, TX: Example Publishing, 2021.

See this article for more information on Chicago style citations.

Types of quotes and examples

There are two main types of quotes: direct and indirect.

Whenever you want to use someone’s statement word-for-word in your text, you’ll need to include properly cited, direct quotations. However, if you want to paraphrase someone’s words then indirect quotes could be more appropriate.

For example, say that you’re writing a press release for a company. You could interview different people within the company’s staff and paraphrase their quotes. This is particularly useful if the direct quote wouldn’t work well within your piece. For instance, you could change this direct quote example into an indirect quote that would more succinctly represent the speech:

Direct quote:

Indirect quote:

Keep in mind when using quotations that you should aim for using as few words as necessary. You don’t want to quote an entire paragraph when only one sentence contains the key information you want to share. If you need to add context, do so in your words. It’ll make for a much more interesting piece if you’re using quotes to support your stance alongside your interpretation instead of just repeating what’s already been said.

--> “A wide screen just makes a bad film twice as bad.” -->

May Habib CEO, Writer.com

Here’s what else you should know about Ascending.

More resources

– 9 min read

‘Be a goldfish’ and other Ted Lasso wisdom for content designers

Jamie Wallace

– 6 min read

Point of view: a complete guide

Irony: definition, types, and examples

Holly Stanley

Home / Guides / Citation Guides / Citation Basics / Quoting vs. Paraphrasing vs. Summarizing

Quoting vs. Paraphrasing vs. Summarizing

If you’ve ever written a research essay, you know the struggle is real. Should you use a direct quote? Should you put it in your own words? And how is summarizing different from paraphrasing—aren’t they kind of the same thing?

Knowing how you should include your source takes some finesse, and knowing when to quote directly, paraphrase, or summarize can make or break your argument. Let’s take a look at the nuances among these three ways of using an outside source in an essay.

What is quoting?

The concept of quoting is pretty straightforward. If you use quotation marks, you must use precisely the same words as the original , even if the language is vulgar or the grammar is incorrect. In fact, when scholars quote writers with bad grammar, they may correct it by using typographical notes [like this] to show readers they have made a change.

“I never like[d] peas as a child.”

Conversely, if a passage with odd or incorrect language is quoted as is, the note [sic] may be used to show that no changes were made to the original language despite any errors.

“I never like [sic] peas as a child.”

The professional world looks very seriously on quotations. You cannot change a single comma or letter without documentation when you quote a source. Not only that, but the quote must be accompanied by an attribution, commonly called a citation. A misquote or failure to cite can be considered plagiarism.

When writing an academic paper, scholars must use in-text citations in parentheses followed by a complete entry on a references page. When you quote someone using MLA format , for example, it might look like this:

“The orphan is above all a character out of place, forced to make his or her own home in the world. The novel itself grew up as a genre representing the efforts of an ordinary individual to navigate his or her way through the trials of life. The orphan is therefore an essentially novelistic character, set loose from established conventions to face a world of endless possibilities (and dangers)” (Mullan).

This quote is from www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/orphans-in-fiction , which discusses the portrayal of orphans in Victorian English literature. The citation as it would look on the references page (called Works Cited in MLA) is available at the end of this guide.

What is paraphrasing?

Paraphrasing means taking a quote and putting it in your own words.

You translate what another writer has said into terms both you and your reader can more easily understand. Unlike summarizing, which focuses on the big picture, paraphrasing is involved with single lines or passages. Paraphrasing means you should focus only on segments of a text.

Paraphrasing is a way for you to start processing the information from your source . When you take a quote and put it into your own words, you are already working to better understand, and better explain, the information.

The more you can change the quote without changing the original meaning , the better. How can you make significant changes to a text without changing the meaning?

Here are a few paraphrasing techniques:

- Use synonyms of words

- Change the order of words

- Change the order of clauses in the sentences

- Move sentences around in a section

- Active – passive

- Positive – negative

- Statement-question

Let’s look at an example. Here is a direct quote from the article on orphans in Victorian literature:

“It is no accident that the most famous character in recent fiction – Harry Potter – is an orphan. The child wizard’s adventures are premised on the death of his parents and the responsibilities that he must therefore assume. If we look to classic children’s fiction we find a host of orphans” (Mullan).

Here is a possible paraphrase:

It’s not a mistake that a well-known protagonist in current fiction is an orphan: Harry Potter. His quests are due to his parents dying and tasks that he is now obligated to complete. You will see that orphans are common protagonists if you look at other classic fiction (Mullan).

What differences do you spot? There are synonyms. A few words were moved around. A few clauses were moved around. But do you see that the basic structure is very similar?

This kind of paraphrase might be flagged by a plagiarism checker. Don’t paraphrase like that.

Here is a better example:

What is the most well-known fact about beloved character, Harry Potter? That he’s an orphan – “the boy who lived”. In fact, it is only because his parents died that he was thrust into his hero’s journey. Throughout classic children’s literature, you’ll find many orphans as protagonists (Mullan).

Do you see that this paraphrase has more differences? The basic information is there, but the structure is quite different.

When you paraphrase, you are making choices: of how to restructure information, of how to organize and prioritize it. These choices reflect your voice in a way a direct quote cannot, since a direct quote is, by definition, someone else’s voice.

Which is better: Quoting or paraphrasing?

Although the purpose of both quoting and paraphrasing is to introduce the ideas of an external source, they are used for different reasons. It’s not that one is better than the other, but rather that quoting suits some purposes better, while paraphrasing is more suitable for others.

A direct quote is better when you feel the writer made the point perfectly and there is no reason to change a thing. If the writer has a strong voice and you want to preserve that, use a direct quote.

For example, no one should ever try to paraphrase John. F. Kenney’s famous line: “Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.”

However, think of direct quotes like a hot pepper: go ahead and sprinkle them around to add some spice to your paper, but… you might not want to overdo it.

Conversely, paraphrasing is useful when you want to bring in a longer section of a source into your piece, but you don’t have room for the full passage . A paraphrase doesn’t simplify the passage to an extreme level, like a summary would. Rather, it condenses the section of text into something more useful for your essay. It’s also appropriate to paraphrase when there are sentences within a passage that you want to leave out.

If you were to paraphrase the section of the article about Victorian orphans mentioned earlier, you might write something like this:

Considering the development of the novel, which portrayed everyday people making their way through life, using an orphan as a protagonist was effective. Orphans are characters that, by definition, need to find their way alone. The author can let the protagonist venture out into the world where the anything, good or bad, might happen (Mullan).

You’ll notice a couple of things here. One, there are no quotation marks, but there is still an in-text citation (the name in parentheses). A paraphrase lacks quotation marks because you aren’t directly quoting, but it still needs a citation because you are using a specific segment of the text. It is still someone else’s original idea and must be cited.

Secondly, if you look at the original quote, you’ll see that five lines of text are condensed into four and a half lines. Everything the author used has been changed.

A single paragraph of text has been explained in different words—which is the heart of paraphrasing.

What is summarizing?

Next, we come to summarizing. Summarizing is on a much larger scale than quoting or paraphrasing. While similar to paraphrasing in that you use your own words, a summary’s primary focus is on translating the main idea of an entire document or long section.

Summaries are useful because they allow you to mention entire chapters or articles—or longer works—in only a few sentences. However, summaries can be longer and more in-depth. They can actually include quotes and paraphrases. Keep in mind, though, that since a summary condenses information, look for the main points. Don’t include a lot of details in a summary.

In literary analysis essays, it is useful to include one body paragraph that summarizes the work you’re writing about. It might be helpful to quote or paraphrase specific lines that contribute to the main themes of such a work. Here is an example summarizing the article on orphans in Victorian literature:

In John Mullan’s article “Orphans in Fiction” on bl.uk.com, he reviews the use of orphans as protagonists in 19 th century Victorian literature. Mullan argues that orphans, without family attachments, are effective characters that can be “unleashed to discover the world.” This discovery process often leads orphans to expose dangerous aspects of society, while maintaining their innocence. As an example, Mullan examines how many female orphans wind up as governesses, demonstrating the usefulness of a main character that is obligated to find their own way.

This summary includes the main ideas of the article, one paraphrase, and one direct quote. A ten-paragraph article is summarized into one single paragraph.

As for giving source credit, since the author’s name and title of the source are stated at the beginning of the summary paragraph, you don’t need an in-text citation.

How do I know which one to use?

The fact is that writers use these three reference types (quoting, paraphrasing, summarizing) interchangeably. The key is to pay attention to your argument development. At some points, you will want concrete, firm evidence. Quotes are perfect for this.

At other times, you will want general support for an argument, but the text that includes such support is long-winded. A paraphrase is appropriate in this case.

Finally, sometimes you may need to mention an entire book or article because it is so full of evidence to support your points. In these cases, it is wise to take a few sentences or even a full paragraph to summarize the source.

No matter which type you use, you always need to cite your source on a References or Works Cited page at the end of the document. The MLA works cited entry for the text we’ve been using today looks like this:

Mullan, John. Orphans in Fiction” www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/orphans-in-fiction. Accessed 20. Oct. 2020

————–

See our related lesson with video: How to Quote and Paraphrase Evidence

Citation Guides

- Annotated Bibliography

- Block Quotes

- Citation Examples

- et al Usage

- In-text Citations

- Page Numbers

- Reference Page

- Sample Paper

- APA 7 Updates

- View APA Guide

- Bibliography

- Works Cited

- MLA 8 Updates

- View MLA Guide

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

Citation Basics

Harvard Referencing

Plagiarism Basics

Plagiarism Checker

Upload a paper to check for plagiarism against billions of sources and get advanced writing suggestions for clarity and style.

Get Started

Table of Contents

Ai, ethics & human agency, collaboration, information literacy, writing process, quotation – when & how to use quotes in your writing.

- © 2023 by Joseph M. Moxley - University of South Florida

What is a Quotation?

A quotation refers to the precise replication of words or phrases from another source, embedded within one’s own writing or speech. To distinguish these directly borrowed elements from original content, writers use quotation marks. Additionally, they provide citations or footnotes to trace back to the original source, maintaining the integrity of the content.

Related Concepts: Copyright ; Information Has Value ; Inserting or Altering Words in a Direct Quotation ; Intellectual Property ; Omitting Words from a Direct Quotation ; Plagiarism ; Scholarship as a Conversation

Why Does Quotation Matter?

When writers incorporate quotations, they aren’t merely borrowing words. They’re strategically weaving the collective wisdom of past thinkers into their narrative, bolstering their arguments, and enhancing their credibility .

- Recognition of Scholarly Foundations: Quotations enable writers to highlight and pay respect to the foundational works, insights, and contributions of past scholars, researchers, and theorists. By doing so, they acknowledge the deep roots of knowledge and ideas that have paved the way for present-day discussions and discoveries.

- Authentic Representation in Discourse: Quotations preserve the precise wording of an author, grounding the reader directly in the original discourse. Unlike paraphrases or summaries , which reinterpret or condense an author’s message, quotations maintain the unaltered essence, subtleties, and nuances of the original statement.

- Validation: Quotations may function as compelling evidence , fortifying the claims a writer has made in their argument

- Building upon Established Knowledge: Quotations illuminate existing ideas, paving the way for writers to elaborate on, challenge, or pivot them toward new directions.

- Preservation of Nuance: Quotations capture the intricate subtleties of unique expressions and poetic language, ensuring that their inherent meaning remains unaltered.

- Positioning within a Discourse: Through quotations, writers can align or differentiate themselves within specific intellectual landscapes, debates, or traditions.

- Credibility: Meticulous citation and thoughtful quotation are hallmarks of a diligent writer, revealing their commitment to professional and ethical codes of conduct.

What Do Writers Quote in Academic and Professional Writing

In both academic and professional writing , quotation serves multiple functions:

- Authenticity and Credibility : Quoting directly from a source provides evidence that the information is based on established research or authoritative accounts . It adds weight to arguments, showcasing that they aren’t merely opinions but are backed by recognized studies or experts in the field.

- Respect for Copyright & Intellectual Property : Academic and workplace writers, trained in critical literacy skills , follow citation conventions meticulously. This diligence stems from their respect for copyright laws and the broader principles of intellectual property . Properly citing and quoting indicates an acknowledgment of the original creator’s contribution and ensures that their work is not appropriated without due credit.

- Preserving Original Meaning: Paraphrasing or summarizing can sometimes inadvertently alter the original meaning or nuance of a text. Quoting ensures that the exact words and context provided by the original author are retained.

- Engaging the Reader: Quotations can be used strategically to capture the reader’s attention. A well-chosen quote can make an article or essay more engaging, invoking curiosity or emphasizing a point.

- Paying Homage: Quoting acknowledges the original creators of content. It’s a form of respect, indicating that their words have made an impact and are deemed worthy of repetition and recognition.

- Avoiding Plagiarism : In academic and professional contexts, using someone else’s words or ideas without proper citation is considered unethical and can have serious repercussions. Quoting, accompanied by appropriate citation, ensures that credit is given where it’s due.

- Enriching Content: Quotations can introduce diverse voices and perspectives into a piece of writing. They can be used to support or counter arguments, provide alternative viewpoints, or illustrate a point more vividly.

- Encouraging Deeper Engagement: When readers encounter a quotation, especially one from a recognized authority or a profound piece of literature, it prompts them to reflect on its meaning, perhaps encouraging them to seek out the original source and engage more deeply with the topic .

- Clarifying Complex Ideas: At times, original texts may communicate complex ideas in a way that’s particularly clear or compelling. Quoting such passages can assist the writer in conveying these complexities without the risk of oversimplification.

When Should You Use Quotations in Your Writing?

There are five major reasons for using quotations:

- Evidential Support: To back up claims or arguments with concrete evidence .

- Illustrative Purposes: To give specific examples or to illuminate a point .

- Eloquence and Impact: Sometimes, the original phrasing is so poignant or well-expressed that paraphrasing might dilute its power or clarity.

- Appeal to Authority: Quoting renowned figures or experts can bolster the credibility of an argument .

- Attribution : To give credit to the original source or author and avoid plagiarism .

When Should I Quote as Opposed to Paraphrasing or Summarizing?

Quoting, paraphrasing , and summarizing are all essential techniques in writing , allowing writers to incorporate the ideas of others into their work.

In general, however, because readers do not want to read miscellaneous quotations that are thrown together one after another, you are generally better off paraphrasing and summarizing material and using direct quotations sparingly. Students—from middle school, college, through graduate school—sometimes believe loads of quotations bring a great deal of credibility , ethos , to the text . Yet, if too many quotes are provided, the text loses clarity .

Like everything else in life, balance is the key. The problem with texts that use extensive direct quotations is that they tend to take attention away from the writer’s voice , purpose , thesis . If you offer quotations every few lines, your ideas become subordinate to other people’s ideas and voices, which often contradicts your instructor’s reasons for assigning research papers—that is, to learn what you think about a subject.

Below are some general strategies you might consider when determine it’s best to quote, paraphrase, or summarize:

- Heart of the Argument: When a passage directly encapsulates the essence of the discussion, quoting ensures the original message isn’t diluted.

- Eloquence & Precision: Some texts are so beautifully articulated or precisely worded that rephrasing would diminish their impact or clarity .

- Eyewitness Accounts: Dramatic firsthand accounts of events can lose their emotional potency if not presented verbatim.

- Influential Authorities: Quoting recognized experts or influential figures can lend credibility to an argument .

- Pertinent Data: Specific statistics or data points, when exactness is crucial, should be quoted directly.

- Challenging to Rephrase: Some complex ideas or specialized terminologies can be hard to rephrase without altering the original meaning.

Paraphrasing

- Clarification: When the original text is dense or hard to understand, a paraphrase can clarify the message for the reader.

- Integration: To weave source material more seamlessly into one’s writing, a paraphrase can be more fluid than a direct quote.

- Modification: If a writer wishes to emphasize a particular aspect of the source material or adapt it for a different audience , paraphrasing allows for this flexibility.

Summarizing

- Overview: Summaries are excellent for providing readers with a snapshot of a larger work or body of research.

- Brevity: When the main gist of a longer text is relevant, but details aren’t necessary, summarizing captures the essence in fewer words.

In all cases, whether quoting, paraphrasing, or summarizing, proper attribution is vital to respect the original author’s intellectual property and to provide readers with a clear path to the primary source.

Is It Okay to Edit Quotations for Brevity and Clarity ?

Yes, editing quotations for clarity and brevity is often necessary, especially when you want to emphasize your own voice and perspective in your writing . Utilizing direct quotations from reliable sources enhances your credibility , but extensive quotations can overshadow your voice and detract from your main argument . Responsible writers prioritize both the quality and the quantity of their quotations, selecting only the most pertinent words or phrases to articulate their points effectively.

How Can I Effectively Shorten a Quote?

- Opt for integrating the part of a quotation that is most impactful, concise, and uniquely expressive.

- Extract only the key segments of the quote that align with your argument , employing ellipses where you omit sections.

- Aim for quotations that span no more than two lines.

- Adhere to the 10% rule: quotations shouldn’t exceed 10% of your paper’s total word count.

- Always respect guidelines given by instructors or publishers regarding quotation length.

Example: Trimming a Quote for Brevity

Original quote:.

“Hand-washing is especially important for children in child care settings. Young children cared for in groups outside the home are at greater risk of respiratory and gastrointestinal diseases, which can easily spread to family members and other contacts. Be sure your child care provider promotes frequent hand-washing or use of alcohol-based hand sanitizers. Ask whether the children are required to wash their hands several times a day — not just before meals.” (“Hand-washing: Do’s and Don’ts” 2)

Revised Quote with Context :

Parents should be concerned about their child’s hand-washing habits—not only under supervision at home, but when the child is being cared for by others. Experts from the Mayo Clinic staff advise that “[h]and-washing is especially important for children in child care settings. . . . Be sure your child care provider promotes frequent hand-washing” (“Hand-washing: Do’s and Don’ts” 2).

What is the Purpose of Ellipses in Quotations?

Ellipses, represented by three dots ( . . . ), indicate that a portion of the original text has been removed for brevity , relevance, or clarity.

How Should Ellipses Be Formatted Within a Quotation?

- Spacing : There should be a space before, between, and after each of the dots. Example :“Original thought . . . remains crucial.”

When Is It Appropriate to Use Ellipses in a Quotation?

- To remove non-essential information that doesn’t alter the quote’s original meaning.

- To make the quotation fit seamlessly into the writer’s sentence or argument.

Are There Any Cautions to Consider When Using Ellipses?

- Avoid altering the original intent or meaning of the quotation.

- Refrain from overusing ellipses; excessive omissions can make the quote unclear or misleading.

- Do not start or end a quotation with ellipses, unless it’s essential to convey that the quote is part of a larger context.

How Do I Use Ellipses After a Complete Sentence?

If you’re omitting content following a complete sentence, the ellipsis points should come after the sentence’s ending punctuation.

Correct : “He enjoyed the evening. . . . They discussed various topics.”

Incorrect : “He enjoyed the evening. . . They discussed various topics.”

Remember, while ellipses help in streamlining quotations, they should be used judiciously to ensure the integrity of the original text remains intact.

Can I Make Changes to Quotations? If So, How to Do I Alert My Readers to Those Changes?

- Purpose of Brackets in Quotations : Brackets [ ] are used to insert or alter words in a direct quotation for clarity, explanation, or integration.

- Example: “It [driving] imposes a heavy procedural workload on cognition…”

- Reminder: The word ‘driving’ clarifies the pronoun ‘it’.

- Example: “[D]riving imposes a heavy procedural workload [visual and motor demands] on cognition…”

- Point: Brackets offer deeper insights on the “procedural workload”.

- Example: Salvucci and Taatgen propose that “[t]he heavy cognitive workload of driving suggests…”

- Note: The change from uppercase ‘T’ to lowercase ‘t’ is indicated with brackets.

- Example: “Drivers [are] increasingly engaging in secondary tasks while driving.”

- Note: The verb changes from past to present tense, and this change is enclosed in brackets.

- Incorrect: “It (driving) imposes a heavy procedural workload…”

- Correct: “It [driving] imposes a heavy procedural workload…”

- A Key Caution : Don’t misuse brackets to alter the original text’s intent or meaning. Always represent the author’s intent accurately.

- Do use brackets to enclose inserted words for clarity or brief explanation.

- Do use brackets to indicate changes in letter case or verb tense.

- Don’t use parentheses in these scenarios.

- Never use bracketed material to twist the author’s original meaning.

Remember, the aim is to ensure clarity and respect the original author’s intent while making the quotation fit seamlessly into your writing.

For More Information on Shortening Quotations, See Also:

- Inserting or Altering Words in a Direct Quotation

- Omitting Words from a Direct Quotation (MLA)

- Omitting Words from a Direct Quotation (APA)

Mayo Clinic Staff. (2021, December 10). Hand-washing: Do’s and don’ts. Mayo Clinic .

Related Articles:

Block quotations, suggested edits.

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Phone This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- Jennifer Janechek

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Credibility & Authority – How to Be Credible & Authoritative in Speech & Writing

Have a thesis expert improve your writing

Check your thesis for plagiarism in 10 minutes, generate your apa citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Working with sources

- How to Paraphrase | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

How to Paraphrase | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

Published on 8 April 2022 by Courtney Gahan and Jack Caulfield. Revised on 15 May 2023.

Paraphrasing means putting someone else’s ideas into your own words. Paraphrasing a source involves changing the wording while preserving the original meaning.

Paraphrasing is an alternative to quoting (copying someone’s exact words and putting them in quotation marks ). In academic writing, it’s usually better to paraphrase instead of quoting. It shows that you have understood the source, reads more smoothly, and keeps your own voice front and center.

Every time you paraphrase, it’s important to cite the source . Also take care not to use wording that is too similar to the original. Otherwise, you could be at risk of committing plagiarism .

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

How to paraphrase in five easy steps, how to paraphrase correctly, examples of paraphrasing, how to cite a paraphrase, paraphrasing vs quoting, paraphrasing vs summarising, avoiding plagiarism when you paraphrase, frequently asked questions about paraphrasing.

If you’re struggling to get to grips with the process of paraphrasing, check out our easy step-by-step guide in the video below.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

Putting an idea into your own words can be easier said than done. Let’s say you want to paraphrase the text below, about population decline in a particular species of sea snails.

Incorrect paraphrasing

You might make a first attempt to paraphrase it by swapping out a few words for synonyms .

Like other sea creatures inhabiting the vicinity of highly populated coasts, horse conchs have lost substantial territory to advancement and contamination , including preferred breeding grounds along mud flats and seagrass beds. Their Gulf home is also heating up due to global warming , which scientists think further puts pressure on the creatures , predicated upon the harmful effects extra warmth has on other large mollusks (Barnett, 2022).

This attempt at paraphrasing doesn’t change the sentence structure or order of information, only some of the word choices. And the synonyms chosen are poor:

- ‘Advancement and contamination’ doesn’t really convey the same meaning as ‘development and pollution’.

- Sometimes the changes make the tone less academic: ‘home’ for ‘habitat’ and ‘sea creatures’ for ‘marine animals’.

- Adding phrases like ‘inhabiting the vicinity of’ and ‘puts pressure on’ makes the text needlessly long-winded.

- Global warming is related to climate change, but they don’t mean exactly the same thing.

Because of this, the text reads awkwardly, is longer than it needs to be, and remains too close to the original phrasing. This means you risk being accused of plagiarism .

Correct paraphrasing

Let’s look at a more effective way of paraphrasing the same text.

Here, we’ve:

- Only included the information that’s relevant to our argument (note that the paraphrase is shorter than the original)

- Retained key terms like ‘development and pollution’, since changing them could alter the meaning

- Structured sentences in our own way instead of copying the structure of the original

- Started from a different point, presenting information in a different order

Because of this, we’re able to clearly convey the relevant information from the source without sticking too close to the original phrasing.

Explore the tabs below to see examples of paraphrasing in action.

- Journal article

- Newspaper article

- Magazine article

Once you have your perfectly paraphrased text, you need to ensure you credit the original author. You’ll always paraphrase sources in the same way, but you’ll have to use a different type of in-text citation depending on what citation style you follow.

Generate accurate citations with Scribbr

It’s a good idea to paraphrase instead of quoting in most cases because:

- Paraphrasing shows that you fully understand the meaning of a text

- Your own voice remains dominant throughout your paper

- Quotes reduce the readability of your text

But that doesn’t mean you should never quote. Quotes are appropriate when:

- Giving a precise definition

- Saying something about the author’s language or style (e.g., in a literary analysis paper)

- Providing evidence in support of an argument

- Critiquing or analysing a specific claim

A paraphrase puts a specific passage into your own words. It’s typically a similar length to the original text, or slightly shorter.

When you boil a longer piece of writing down to the key points, so that the result is a lot shorter than the original, this is called summarising .

Paraphrasing and quoting are important tools for presenting specific information from sources. But if the information you want to include is more general (e.g., the overarching argument of a whole article), summarising is more appropriate.

When paraphrasing, you have to be careful to avoid accidental plagiarism .

Students frequently use paraphrasing tools , which can be especially helpful for non-native speakers who might have trouble with academic writing. While these can be useful for a little extra inspiration, use them sparingly while maintaining academic integrity.

This can happen if the paraphrase is too similar to the original quote, with phrases or whole sentences that are identical (and should therefore be in quotation marks). It can also happen if you fail to properly cite the source.

To make sure you’ve properly paraphrased and cited all your sources, you could elect to run a plagiarism check before submitting your paper.

To paraphrase effectively, don’t just take the original sentence and swap out some of the words for synonyms. Instead, try:

- Reformulating the sentence (e.g., change active to passive , or start from a different point)

- Combining information from multiple sentences into one

- Leaving out information from the original that isn’t relevant to your point

- Using synonyms where they don’t distort the meaning

The main point is to ensure you don’t just copy the structure of the original text, but instead reformulate the idea in your own words.

Paraphrasing without crediting the original author is a form of plagiarism , because you’re presenting someone else’s ideas as if they were your own.

However, paraphrasing is not plagiarism if you correctly reference the source . This means including an in-text referencing and a full reference , formatted according to your required citation style (e.g., Harvard , Vancouver ).

As well as referencing your source, make sure that any paraphrased text is completely rewritten in your own words.

Plagiarism means using someone else’s words or ideas and passing them off as your own. Paraphrasing means putting someone else’s ideas into your own words.

So when does paraphrasing count as plagiarism?

- Paraphrasing is plagiarism if you don’t properly credit the original author.

- Paraphrasing is plagiarism if your text is too close to the original wording (even if you cite the source). If you directly copy a sentence or phrase, you should quote it instead.

- Paraphrasing is not plagiarism if you put the author’s ideas completely into your own words and properly reference the source .

To present information from other sources in academic writing , it’s best to paraphrase in most cases. This shows that you’ve understood the ideas you’re discussing and incorporates them into your text smoothly.

It’s appropriate to quote when:

- Changing the phrasing would distort the meaning of the original text

- You want to discuss the author’s language choices (e.g., in literary analysis )

- You’re presenting a precise definition

- You’re looking in depth at a specific claim

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Gahan, C. & Caulfield, J. (2023, May 15). How to Paraphrase | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 14 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/working-sources/paraphrasing/

Is this article helpful?

Courtney Gahan

Other students also liked, harvard in-text citation | a complete guide & examples, how to avoid plagiarism | tips on citing sources, apa referencing (7th ed.) quick guide | in-text citations & references.

Quoting & Paraphrasing: Home

Quoting and paraphrasing quick tips.

In general, it is best to use a quote when:

- The exact words of your source are important for the point you are trying to make. This is especially true if you are quoting technical language, terms, or very specific word choices.

- You want to highlight your agreement with the author’s words. If you agree with the point the author of the evidence makes and you like their exact words, use them as a quote.

- You want to highlight your disagreement with the author’s words. In other words, you may sometimes want to use a direct quote to indicate exactly what it is you disagree about. This might be particularly true when you are considering the antithetical positions in your research writing projects.

In general, it is best to paraphrase when:

- There is no good reason to use a quote to refer to your evidence. If the author’s exact words are not especially important to the point you are trying to make, you are usually better off paraphrasing the evidence.

- You are trying to explain a particular a piece of evidence in order to explain or interpret it in more detail. This might be particularly true in writing projects like critiques.