An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Psychol Res Behav Manag

A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews on Blended Learning: Trends, Gaps and Future Directions

Muhammad azeem ashraf.

1 Research Institute of Education Science, Hunan University, Changsha, People’s Republic of China

Meijia Yang

Yufeng zhang, mouna denden.

2 Research Laboratory of Technologies of Information and Communication & Electrical Engineering (LaTICE), Tunis Higher School of Engineering (ENSIT), Tunis, Tunisia

Ahmed Tlili

3 Smart Learning Institute, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, People’s Republic of China

4 School of Professional Studies, Columbia University, New York City, NY, USA

Ronghuai Huang

Daniel burgos.

5 Research Institute for Innovation & Technology in Education (UNIR iTED), Universidad Internacional de La Rioja (UNIR), Logroño, 26006, Spain

Blended Learning (BL) is one of the most used methods in education to promote active learning and enhance students’ learning outcomes. Although BL has existed for over a decade, there are still several challenges associated with it. For instance, the teachers’ and students’ individual differences, such as their behaviors and attitudes, might impact their adoption of BL. These challenges are further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, as schools and universities had to combine both online and offline courses to keep up with health regulations. This study conducts a systematic review of systematic reviews on BL, based on PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines, to identify BL trends, gaps and future directions. The obtained findings highlight that BL was mostly investigated in higher education and targeted students in the first place. Additionally, most of the BL research is coming from developed countries, calling for cross-collaborations to facilitate BL adoption in developing countries in particular. Furthermore, a lack of ICT skills and infrastructure are the most encountered challenges by teachers, students and institutions. The findings of this study can create a roadmap to facilitate the adoption of BL. The findings of this study could facilitate the design and adoption of BL which is one of the possible solutions to face major health challenges, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Introduction

Blended Learning (BL) is one of the most frequently used approaches related to the application of Information and Communications Technology (ICT) in education. 1 In its simplest definition, BL aims to combine face-to-face (F2F) and online settings, resulting in better learning engagement and flexible learning experiences, with rich settings way further the use of a simple online content repository to support the face-to-face classes. 2 , 3 Researchers and practitioners have used different terms to refer to the blended learning approach, including “brick and click” instruction, 4 hybrid learning, 4 dual-mode instruction, 5 blended pedagogies, 4 HyFlex learning, 6 targeted learning, 4 multimodal learning and flipped learning. 3

Researchers and practitioners have pointed out that designing BL experiences could be complex, as several features need to be considered, including the quality of learning experiences, learning instruction, learning technologies/tools and applied pedagogies. 7–9 Therefore, they have focused on investigating different BL perspectives since 2000. 10 Despite this 21-year investigation and research, there are still several challenges and unanswered questions related to BL, including the quality of the designed learning materials 9 , 11 , 12 applied learning instructions, 9 the culture of resisting this approach, 13 , 14 and teachers being overloaded when applying BL. 15 The COVID-19 pandemic has further highlighted the challenges associated with BL. Specifically, international universities and schools worldwide had to take several actions with respect to health regulations, such as reducing classroom sizes. 16 Therefore, they combined online and offline learning to maintain their courses for both on-campus and off-campus experiences. 16 For instance, as a response to the effort made by the government of Indonesia to carry out physical distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic, in all domains including education, some elementary schools used BL with Moodle platform to ensure the continuity of learning. 17 In this context, several teachers raised concerns about implementing BL experiences, such as the lack of infrastructure and competencies to do so, calling for further investigation in this regard. Several international organizations, such as UNESCO and ILO, claimed that teacher professional development for online and blended learning is one of the priorities for building resilient education systems for the future. 18

Based on the background above, it is seen that there is still room for discussion of designing and implementing effective BL. Researchers have suggested that conducting literature reviews can help identify challenges and solutions in a given domain. 19–21 Review papers may serve the development of new theories and also shape future research studies, as well as disseminate knowledge to promote scientific discussion and reflection about concepts, methods and practices. However, several BL systematic reviews were conducted in the literature which are of variable quality, focus and geographical region. This made the BL literature fragmented, where no study provides a comprehensive summary that could be a reference for different stakeholders to adopt BL. In this context, Smith et al mentioned that a logical and appropriate next step is to conduct a systematic review of reviews of the topic under consideration, allowing the findings of separate reviews to be compared and contrasted, thereby providing comprehensive and in-depth findings for different stakeholders. 22 As BL is becoming the new normal, 23 this study takes a step further beyond simply conducting a systematic review and conducts a systematic review of systematic reviews on BL. By systematically examining high-quality published literature review articles, this study reveals the reported BL trends and challenges, as well as research gaps and future paths. These findings could help different stakeholders (eg, policy makers, teachers, instructional designers, etc.) to facilitate the design and adoption of BL worldwide. Although several systematic reviews of literature reviews have been conducted in different fields, such as engineering, 24 healthcare 25 and tourism, 26 no one was conducted on blended learning, to the best of our knowledge. It should be noted that one study was conducted in this context, but it mainly focused on the transparency of the systematic reviews that were conducted 27 and was not about the BL field itself.

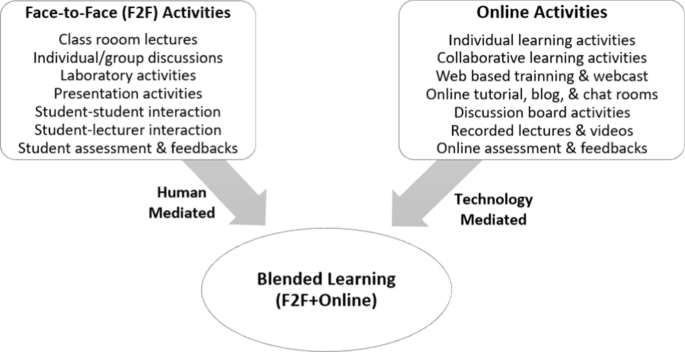

Guided by the technology-based learning model (see Figure 1 ), this study aims to answer the following six research questions:

Blended learning model.

RQ1. What are the trends of blended learning research in terms of: publication year, geographic region and publication venue?

RQ2. What are the covered subject areas in blended learning research?

RQ3. Who are the covered participants (stakeholders) in blended learning research?

RQ4. What are the most frequently used research methods (in systematic reviews) in blended learning research?

RQ5. How blended learning was designed in terms of the used learning models and technologies?

RQ6. What are the learning outcomes of blended learning, as well as the associated challenges?

The findings of this study could help to analyze the behaviors and attitudes of different stakeholders from different BL contexts, hence draw a comprehensive understanding of BL and its impact from different international perspectives. This can promote cross-country collaboration and more open BL design that more worldwide universities could be involved in. The findings could also facilitate the design (eg, in terms of the used learning models and technologies) and adoption of BL which is one of the possible solutions to face major health challenges, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methodology

This study presents a systematic review of systematic review papers on BL. In particular, this review follows the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines. 28 PRISMA provides a standard peer-accepted methodology that uses a guideline checklist, which was strictly followed for this study, to contribute to the quality assurance of the revision process and to ensure its replicability. A review protocol was developed, describing the search strategy and article selection criteria, quality assessment, data extraction and data analysis procedures.

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

To deal with this topic, an extensive search for research articles was undertaken in the most common and highly valued electronic databases: Web of Science, Scopus and Google Scholar, 29 using the following search strings.

Search string: ((blending learning substring) AND (literature review substring))

Blended learning substring: “Blended learning” OR “blended education” OR “hybrid learning” OR “flipped classroom” OR “flipped learning” OR “inverted classroom” OR “mixed-mode instruction” OR “HyFlex learning”

Literature review substring: “Review” OR “Systematic review” OR “state-of-art” OR “state of the art” OR “state of art” OR “meta-analysis” OR “meta analytic study” OR “mapping stud*” OR “overview”

Databases were searched separately by two of the authors. After searching the relevant databases, the two authors independently analyzed the retrieved papers by titles and abstracts, and papers that clearly were not systematic reviews, such as empirical, descriptive and conceptual papers, were excluded. Then, the two authors independently performed an eligibility assessment by carefully screening the full texts of the remaining papers, based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria described in Table 1 . During this phase, disagreements between the authors were resolved by discussion or arbitration from a third author. Specifically, to provide high-quality papers, this study was restricted to papers published in journals.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

This research yielded a total of 972 articles. After removing duplicated papers, 816 papers remained. 672 papers were then removed based on the screening of titles and abstracts. The remaining 144 papers were considered and assessed as full texts. 85 of these papers did not pass the inclusion criteria. Thus, as a total number, 57 eligible research studies remained for inclusion in the systematic review. Figure 2 presents the study selection process as recommended by the PRISMA group. 28

Flowchart of the systematic review process.

Quality Assessment

For methodological quality evaluation, the AMSTAR assessment tool was used. AMSTAR is widely used as a valuable tool to evaluate the quality of systematic reviews conducted in any academic field. 30 It consists of 11 items that evaluate whether the review was guided by a protocol, whether there was duplicate study selection and data extraction, the comprehensiveness of the search, the inclusion of grey literature, the use of quality assessment, the appropriateness of data synthesis and the documentation of conflicts of interest. Specifically, two authors independently assessed the methodological quality of the included reviews using the AMSTAR checklist. Items were evaluated as “Yes” (meaning the item has been properly handled, 1 point), “No” (indicating the possibility that the item did not perform well, 0 points) or “Not applicable” (in the case of performance failure because the item was not applied, 0 points). Disagreements regarding the AMSTAR score were resolved by discussion or by a decision made by a third author.

Appendix 1 presents the results of the quality assessment of the 57 systematic reviews based on the AMSTAR tool. 19 were rated as being low quality (AMSTAR score 0–4), 30 as being moderate quality (score 5–8), and eight as being high quality (score 9–11). Specifically, no study has acknowledged the conflict of interest in both the systematic review and the included studies. Also, few studies provided the list of the included and excluded studies (3 out of 57), and reported the method used to combine the findings of the studies (13 out of 57). About half of the included studies assessed the scientific quality of the included studies (25 out of 57), but all the studies fulfilled at least one quality criterion.

Data Extraction

This study adapted the technology-based learning model, 31 which has been used in BL contexts, 32 , 33 as shown in Figure 1 . This model is based on six factors: subject area, learning models, participants, outcomes and issues, research methods and adopted technologies. The current study adopted most of the schemes from this model but made slight adjustments according to the features of different models in blended learning. Table 2 presents a detailed description of the coding scheme that was used in this study to answer the aforementioned research questions.

The Coding Scheme for Analyzing the Collected Papers

Results and Discussion

Blended learning trends.

Figure 3 shows that the first two systematic reviews on BL were conducted in 2012. The first, by Keengwe and Kang, 34 investigated the effectiveness of BL practices in the teacher education field. The second was by Rowe et al, 35 which investigated how to incorporate BL in clinical settings and health education. These findings show an early interest in providing teachers with the necessary competencies and skills to use BL, as well as in enhancing health education, where students need more practical knowledge and skills that could be facilitated through BL (eg, simulation health videos, virtual labs, etc.). The number of literature reviews conducted has since increased, showing an increased interest in BL over the years. Specifically, the highest peak of literature reviews conducted on blended learning was in 2020 (16 studies). This might be due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced most institutions worldwide to implement BL (online merged with offline) to accommodate the needs of learners in this disruptive time. 18 This has encouraged many institutions to make their own attempts to practice BL and thus furthered the research interest in examining the best practices of BL.

Distribution of studies by publication year.

Additionally, according to the authors’ affiliation countries (see Figure 4 ), China and the United States have the highest number of publications, with nine and seven studies respectively. This could be explained by the continuous rapid evolution of the technological education industry in both China and the United States, 36 which has made researchers and educators innovate to provide more flexible learning experiences by combining both online and offline environments. 37 This could also be explained by the number of blended learning policies that have been issued in these two countries to facilitate blended learning adoption. 38 , 39

Distribution of studies per country.

Interestingly, while several studies are from Europe (eg, Belgium, the UK, Italy, etc.), there are very few studies from the African and Arab regions. Similarly, in BL contexts, Birgili et al 40 conducted a systematic review about flipped learning between 2012 and 2018; they found very few studies coming from Africa. This indicates a trend where countries with more sufficient educational resources and infrastructure are exposed to more chances to develop BL environments and experiences. These findings call for more cross-country collaboration to facilitate the implementation of BL in the countries that have limited knowledge or infrastructure related to BL. For instance, such a collaboration could cover BL policies, ICT trainings and the development of educational resources and technologies.

Finally, the 57 reviews were published in 44 journals. Figure 5 shows the journals that have at least two publications. Education and Information Technologies has the highest number of publications (six studies), followed by Interactive Learning Environments (four studies) and Nurse Education Today (four studies). These journals are mostly from the educational technology and health fields.

Distribution of studies by publication venue.

Subject Area

Figure 6 shows that most of the literature review studies (n = 21) did not mention the covered subject area and discussed BL in general. For example, Wang et al proposed a complex adaptive systems framework to conduct analysis on BL literature. 41 This shows that, despite the popularity of BL, which has existed for a decade, educators and researchers are still finding it to be a complex concept that needs further investigation regardless of the subject. 2

Distribution of studies by subject area.

Other studies considered BL as being context-dependent, 42 investigating it from different subject areas, namely health (14 studies), STEM (five studies) and language (three studies). This could be explained by these three subjects requiring a lot of practical knowledge, such as communication and pronunciation, programming or physical treatments, where the BL concept could provide teachers with a chance to be more innovative and offer students the possibility of practicing this practical knowledge online by using virtual labs or online virtual programming emulators, for instance. Walker et al 43 and Yeonja et al 44 found that BL is considered to be crucial for health students, and health educators have tried to integrate a wide range of advanced technology and learning tools to enhance their skill acquisition.

From these findings, it can be deduced that more research should be conducted to investigate how BL is conducted in other subject areas that are considered crucial for student performance assessment, such as mathematics. This could help researchers and practitioners compare the different BL design and assessment approaches in different subjects and come up with personalized guidelines that could help educators implement their BL in a specific subject. In this context, studies have pointed out that teachers are willing to implement BL in their courses but do not know how. 45 Additionally, as shown in Figure 6 , most of the conducted literature reviews covered limited number of studies (less than 50). Therefore, the future literature reviews on BL should cover more studies (more than 50) to have an in-depth and broad view of how BL is being implemented in different contexts by different researchers.

Participants

As Figure 7A shows, the most targeted participants by the review studies were students (n = 42) followed by teachers (n = 13) and then working adults, health professionals and researchers (one study for each). This analysis shows that none of the review studies have targeted major players in the adoption of BL, such as policy makers. Owston stated that policies on different levels (eg, institutions, faculties, technology use, data collection procedures, learning support, etc.) are crucial to advancing the adoption of BL for future education. 38 Therefore, to advance BL adoption worldwide, more reviews about BL policies and the focus of these policies – including copyright, privacy and data protection, and others, 46 , 47 – should be investigated to develop a BL policy framework to which everyone could refer.

( A ) Distribution by educational level. ( B ) Distribution by participants.

Figure 7B , on the other hand, shows that most of the review studies (n = 33) focused mainly on higher education, followed by K–12 (six studies) and teacher education (five studies). Interestingly, these findings are in line with two older studies that were conducted in 2012 (Halverson et al) 48 and 2013 (Drysdale et al), 49 where they found that BL is mostly applied in higher education. These findings clearly show that, despite the long period of time since 2012, the research setting of BL application has not changed, which calls for more serious efforts and research about BL design in other contexts, such as K–12. Especially since younger students might lack the appropriate self-regulation skills compared to older students that can help them adopt BL, 50 more support should also be provided accordingly. Additionally, as few studies focused on teacher education, more research should investigate how to harness the power of BL for teacher professional development. There are limited empirical findings on BL for teacher professional development, 34 , 51–53 calling for more investigation in this context.

Research Method

Table 3 shows that most reviews conducted were systematic reviews (n = 47). As researchers note, systematic literature reviews are usually composed with a clearly defined objective, a research question, a research approach and inclusion and exclusion criteria. 54–56 Through systematic review, researchers can come to a qualitative conclusion in response to their research question. Only seven reviews conducted meta-analysis to assess the effect size and variability of BL and to identify potential causal factors that can inform practice and further research. Finally, three studies used both systematic reviews and meta-analysis in their studies, which can quantitatively synthesize the results in an even more comprehensive way. For instance, Liu et al 57 first reviewed the literature of the effectiveness of knowledge acquisition in health-subject learners and then conducted a meta-analysis to show that BL had a significant larger pooled effect size than non-BL health-subject learners. In this way, researchers are able to address the extent to which BL is truly effective in the learning. 57 Considering that only three review papers conducted both systematic review and meta-analysis, we must again address the usefulness of quantitative analysis. There are still many unanswered questions that could be addressed in a better way using quantitative analysis. Therefore, future research should consider conducting more meta-analysis in order to provide a better understanding of the nuanced effects of BL.

Distribution of Studies by Research Method and Subject Area

Design (Learning Models and Technologies)

Figure 8 shows that the majority of review studies (33 out of 57) discussed BL as a generic concept and did not mention any specific model. Additionally, the flipped model was the most frequently implemented model, mentioned by 27 review studies. This model is designed based on three stages: pre-class, in-class and post-class (optional). In the pre-class stage, the students engage with the course content through online resources, so that they spend in-class time doing practical activities and having discussions. Then, in the post-class stage, teachers can assess the students’ perceptions and performance in the flipped course. 32

Frequency of usage of blended learning models.

The second most frequently used models were the station rotation model and the flex model (each mentioned by three studies). In the station rotation model, the student can rotate at fixed points of time (on a fixed schedule or at the teacher’s discretion) between different stations, at least one of which is an online learning station). 58 For instance, the students can rotate between face-to-face (F2F) instruction, online instruction and collaborative activities. The flex model, on the other hand, relies entirely on online materials and student self-study, with the availability of F2F teachers when needed. 59

Two review studies mentioned the self-blend (also known as the “à la carte” model) and the enriched virtual model. The first model allows students to take fully online courses with online teachers, in addition to other F2F courses. 60 In the second model, students are asked to be able to conduct F2F sessions with instructors and then can complete their assignments online, but they are not required to attend F2F classes. 60

Finally, only one study applied the mixed model, supplemental model and online practicing model. Specifically, in the mixed model, content delivery and practical activities occur both F2F and online. In the supplemental model, both content delivery and practical activities take place F2F. In contrast, in the online practicing model, students can practice activities through a specific online learning environment. In particular, the reported BL models were implemented differently in many domains. It should be noted that some studies investigated more than one BL model. For instance, Alammary investigated flipped, mixed, flex, supplemental, and online-practicing models. 59

Table 4 presents the distribution of the reviewed studies by BL models and subject areas. 22 studies (seven multiple courses and 15 uncategorized) have focused on the design of BL in general or in multiple courses. This might be explained by the fact that teachers have limited knowledge about BL models that is why they always face challenges on how to design their blended courses and mix the offline and online settings. 58 This blended learning design problem was further emphasized during the COVID-19 pandemic, where several teachers raised concerns about this matter. 61 Therefore, more BL design trainings should be provided for teachers to help them efficiently design their blended courses.

Distribution of Studies by Blended Learning Models and Subject Area

Additionally, the flipped model was frequently used in health (seven studies), followed by STEM (five studies). This may be explained by health and STEM subjects requiring many hands-on practices to promote skill acquisition and long-term retention by the student. 62 , 63 In line with this, the flipped model enables teachers to reduce the in-class time by teaching all the courses online (in the pre-class stage) and counterbalance the students’ workload, so that the class time can be reserved for practical exercises instead of traditional lectures. For instance, in the health domain, the flipped model is applied by explaining the basic concepts of the course using different learning strategies in the pre-class stage, such as online learning platforms, instructional videos, animation, PowerPoint presentations and 3D virtual gaming situations. Also, students can use social media platforms such as Facebook for online discussions. In-class activities include instructor-led training, discussion of issues, practice or doing exercises (eg, assignments or quizzes), clinical teaching (eg, nursing diagnosis training) or lab teaching. In this context, several learning technologies were used, such as traditional computers and projectors, medical or teaching equipment and simulation teaching aids. Finally, in the post-class stage, some teachers used assessment methods to evaluate students’ perception of the applied model using peer evaluation, post-class evaluation and surveys. Similarly, in STEM subjects, the in-class time was reserved for more practice, including complex exercises where students can interact with each other and with the instructor (collaborative group assignments), active learning exercises rather than lectures, gaming activities, examinations and peer instruction.

Furthermore, as Table 4 shows, the mixed, flex, supplemental and online practicing models were also applied in STEM, specifically in programming courses. 59 This may be explained by the fact that STEM subjects – and programming courses in particular – allow for flexibility; combined with emerging technologies, this enables the teaching of this course in different ways, fully online or F2F. 64 For instance, in the mixed model, students received the course content and practical coding exercises in both F2F and online sessions, reserving most of the in-class time for practical exercises and discussion. In this context, in addition to the classical learning strategies such as online self-paced learning, online collaboration and online instructor-led learning, online programming tools were also used for coding and problem solving in online sessions. In the flex model, both course content and practical coding exercises take place online, but students are required to attend F2F sessions from time to time to check their progress or be provided with feedback. In the supplemental model, both course content and practical coding exercises take place F2F. However, online supplemental activities are added to the course to increase students’ engagement with course content. In the online practicing model, an online programming environment is used as the backbone of students’ learning. It allows students to practice programming and problem solving and provides them with immediate feedback about their programming solutions. The delivery of the course content is achieved through lectures and/or self-based online resources. In some cases, online resources are integrated within the online programming environment.

Outcomes and Challenges

Figure 9 presents the different learning outcomes investigated in the 57 review studies based on two categories: psychological and behavioural outcomes. 65 The majority of studies (49 studies) focused on investigating the psychological outcomes within the reviewed studies. Specifically, students’ self-regulation toward learning was the most investigated psychological outcome (10 studies), followed by satisfaction (nine studies) and engagement (eight studies). According to Van Laer and Elen, blended learning design includes attributes that support self-regulation, including authenticity, personalization, learner control, scaffolding and interaction. 66 The 10 studies found that students’ self-regulation was improved. Additionally, BL was found to improve students’ satisfaction and engagement in different domains, especially in health (seven studies). For instance, Li et al 67 and Presti 68 found that flipped learning enhanced students’ engagement and satisfaction in nursing education. Moreover, motivation, attitude, high-order thinking, social interaction and self-efficacy were found to be improved using BL.

Distribution of learning outcomes based on the number of studies addressing them.

The most investigated behavioural outcome is academic performance (26 studies), followed by skill progression and cooperation. In particular, the 26 studies showed that BL supports learning performance in different subject areas, including health, language and STEM. BL can also enhance students’ skills, such as clinical skills in the health domain, 35 , 69 and speaking skills in the language domain. 70 Additionally, its design may include several collaborative learning assignments (online or F2F) that encourage cooperation with students. 71 It should be noted that some studies investigated more than one type of learning outcomes. For instance, Atmacasoy and Aksu investigated students’ engagement with, collaboration in, participation in and academic performance with the blended learning course. 72

Despite the many advantages that BL offers, it also comes with several challenges. Figure 10 presents the most encountered challenges in the 57 review studies. Specifically, the lack of ICT skills is the most mentioned challenge (seven studies), followed by infrastructure issues (six studies) such as internet-related problems and lack of personal computers, course preparation time (three studies), design model and cost of technologies (two studies for each) and course quality content, student engagement and student isolation (one study for each). It should be noted that 47 studies did not mention any challenges and nine studies mentioned more than one challenge each. For instance, Rasheed et al found that students, teachers and institutions may face different challenges in BL, such as students’ isolation, lack of ICT skills for teachers and students and technological provision challenges (eg, cost of online learning technologies) for institutions. 73

Distribution of blended learning challenges.

Both teachers and students from different domains might lack ICT skills, which can negatively influence their adoption of BL. For instance, Atmacasoy and Aksu stated that teachers with low ICT skills may not have positive attitudes toward using BL since it is based on technology use. 72 Teachers might find difficulties in the ease of use of some technologies while creating a BL course, such as in recording videos, uploading videos and using online learning platforms. 73 Additionally, students may face some technological complexity challenges, such as accessing online educational resources or uploading their materials to the online learning environment. 73

ICT infrastructure is also a crucial layer for facilitating and implementing blended courses; however, it is still a major problem for several universities, especially in developing countries 74 and rural areas. 75 For instance, a lack of basic technologies, including internet, computers and projectors can limit the implementation of blended courses. Therefore, it is very important to improve institutes’ ICT infrastructure in order to improve education in general and enable teachers to teach using BL, which has proven to be efficient in many subject areas (see sections above).

In addition to issues with ICT skills and infrastructure, teachers may lack knowledge about designing BL models and hence face difficulties in selecting the appropriate design for their courses, 58 and they may also spend too much time preparing the blended course. 75 , 76 Moreover, some challenges of online learning, such as engagement and students’ isolation, may be faced in BL. In this context, teachers may integrate online collaborative assignments to solve the problem of isolation 77 and integrate new approaches, such as gamification, into the online learning environment in order to make students motivated and engaged while learning online. 78 , 79 In this context, Ekici found that gamified flipped learning enhanced students’ motivation and engagement while learning. 80

This study conducted a systematic review of systematic reviews on BL. It revealed several findings according to each research question: (1) the first two systematic reviews on BL were conducted in 2012, and this number rapidly increased over the years, reflecting a massive interest in BL. Additionally, more cross-country collaboration should be established to facilitate BL implementation in countries that lack, for instance, infrastructure or the needed BL competencies; (2) despite that several studies focused on specific subject area such as health or STEM, most studies did not discuss BL from a specific subject area; (3) most of the studies targeted students as stakeholders, and neglected major key players for BL adoption, such as policy makers; (4) most of the studies conducted a systematic review with qualitative analysis. Therefore, future research should follow a more quantitative approach through meta-analysis in order to provide a better understanding of the nuanced effects of BL; (5) the majority of studies discussed BL as a generic construct and did not focus on the learning models of BL. However, the flipped model was the most frequently implemented model in the papers that focused on learning models specifically in health and STEM ; and (6) BL can affect students’ psychological and behavioural outcomes. In terms of psychological outcomes, it can enhance students’ self-regulation toward learning, satisfaction and engagement while learning in different domains, especially in health. In terms of behavioural outcomes, BL supported students’ academic performance in different subject areas. Additionally, a lack of ICT skills and infrastructure are the most encountered challenges by teachers, students and institutions.

The findings of this study can help create a roadmap about future research on BL. This could facilitate BL adoption worldwide and thus contribute to achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially SDG #4 – equity and high-quality education for all – which works as a backbone for some other SDGs, such as good health (#3), economic Growth (#8) and reduced inequality (#10). Despite the importance of the revealed findings, this study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. For instance, this study used a limited number of search keywords within specific electronic databases.

Future research might focus on: (1) dealing with these limitations; (2) investigating different BL models with specific application domains to test their impacts on students’ psychological and behavioural outcomes; (3) enhancing students’ motivation and engagement in online sessions by integrating new motivational concepts such as gamification in online learning platforms; and (4) dealing with BL challenges by providing some solutions to enhance the learning experience. For instance, for the challenge of a lack of ICT skills, research might work to provide ICT trainings for teachers and students to enhance their skills with technology.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (The Research Fund for International Young Scientists; Grant No. 71950410624). However, any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Advertisement

Blended Learning Adoption and Implementation in Higher Education: A Theoretical and Systematic Review

- Original research

- Open access

- Published: 07 October 2020

- Volume 27 , pages 531–578, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Bokolo Anthony Jr. ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7276-0258 1 ,

- Adzhar Kamaludin 2 ,

- Awanis Romli 2 ,

- Anis Farihan Mat Raffei 2 ,

- Danakorn Nincarean A. L. Eh Phon 2 ,

- Aziman Abdullah 2 &

- Gan Leong Ming 2

53k Accesses

91 Citations

15 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Technological innovations such as blended learning (BL) are rapidly changing teaching and learning in higher education, where BL integrates face to face teaching with web based learning. Thus, as polices related to BL increases, it is required to explore the theoretical foundation of BL studies and how BL were adopted and implemented in relation to students, lecturers and administration. However, only fewer studies have focused on exploring the constructs and factors related to BL adoption by considering the students, lecturers and administration concurrently. Likewise, prior research neglects to explore what practices are involved for BL implementation. Accordingly, this study systematically reviews, synthesizes, and provides meta-analysis of 94 BL research articles published from 2004 to 2020 to present the theoretical foundation of BL adoption and implementation in higher education. The main findings of this study present the constructs and factors that influence students, lecturers and administration towards adopting BL in higher education. Moreover, findings suggest that the BL practices to be implemented comprises of face-to-face, activities, information, resources, assessment, and feedback for students and technology, pedagogy, content, and knowledge for lecturers. Besides, the review reveals that the ad hoc, technology acceptance model, information system success model, the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology, and lastly diffusion of innovations theories are the mostly employed theories employed by prior studies to explore BL adoption. Findings from this study has implications for student, lecturers and administrators by providing insights into the theoretical foundation of BL adoption and implementation in higher education.

Similar content being viewed by others

An analysis of causal factors of blended learning in Thailand

Blended Learning Adoption on Higher Education

Discovering Blended Learning Adoption: An Italian Case Study in Higher Education

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Blended learning (BL) has increasingly been utilized in higher education as it has the advantages of both traditional and online teaching approaches (Poon 2014 ). Findings from prior studies Edward et al. ( 2018 ); Ghazal et al. ( 2018 ) indicated that BL approach enhances students’ learning engagement and experience as it creates a significant influence on students’ awareness of the teaching mode and learning background. BL moves the emphasis from teaching to learning, thus enabling students to become more involved in the learning process and more enthused and, consequently, improves their perseverance and commitment (Ismail et al. 2018a ). Poon ( 2014 ) concluded that BL is likely to be developed as the leading teaching approach for the future as one of the top ten educational trends to occur in the twentyfirst century. Poon ( 2014 ) started that the question is not whether higher education should adopt BL but rather the question should be aligned to the practice that should be included for successfully BL implementation.

The phrase blended learning was previously associated with classroom training to e-learning activities (Graham et al. 2013 ). Accordingly, BL is the integration of traditional face-to face and e-learning teaching paradigm (Wong et al. 2014 ). BL employs a combination of online-mediated and face-to-face (F2F) instruction to help lecturers attain pedagogical goals in training students to produce an algorithmic and constructive rational skill, aids to enhance teaching qualities, and achieve social order (Subramaniam and Muniandy 2019 ). BL entails the combination of different methods of delivery, styles of learning, and types of teaching (Kaur 2013 ). BL is frequently used with terms such as integrated, flexible, mixed mode, multi-mode or hybrid learning (Garrison and Kanuka 2004 ; Moskal et al. 2013 ). BL comprises integration of various initiatives, achieved by combining of 30% F2F interaction with 70% IT mediated learning (Anthony et al. 2019 ). Similarly, Owston et al. ( 2019 ) recommended that a successful BL delivery comprises of 80% high quality online learning integrated with 20% classroom teaching that is linked to online content. Respectively, BL is the combination of different didactic approaches (cooperative learning, discovery learning expository, presentations, etc.) and delivery methods (personal communication, broadcasting, publishing, etc.) (Graham 2013 ; Klentien and Wannasawade 2016 ).

Research has found that online systems possess the capability of providing platforms for competent practices in offering alternative to real-life environment, offering students a usable avenue for learning which support students to improve the quality of learning (Wong et al. 2014 ; Ifenthaler et al. 2015 ). When prudently and accurately deployed, IT can be deployed to achieve a reliable learning experience with practical relevancy to engage and motivate students (Tulaboev 2013 ). Thus, BL facilitates students to not only articulate learning but to also test on the knowledge they have attained through the semester (Aguti et al. 2013 ). Moreover, BL offers flexibility for students and lecturer, improved personalization, improved student outcomes, encourages growth of autonomy and self-directed learning, creates prospects for professional learning, reduced cost proficiencies, increases communication between students and lecturer, and among students (So and Brush 2008 ; Spring et al 2016 ). BL emboldens the reformation of pedagogic policies with the prospective to recapture the ideals of universities (Heinze and Procter 2004 ). BL seeks to produce a harmonious and coherent equilibrium between online access to knowledge and traditional human teaching by considering students' and lecturers' attitudes (Bervell and Umar 2018 ). BL therefore remains a significant pedagogical concept as its main focus is aligned with providing the most effective teaching and learning experience (Wang et al. 2004 ).

BL offers access to online resources and information that meet the students’ level of knowledge and interest. It supports teaching conditions by offering opportunities for professional collaboration, and also improve time adeptness of lecturers (Guillén-Gámez et al. 2020 ; Owston et al. 2019 ). BL proliferates students’ interest in their individual learning progression (Chang-Tik 2018 ), facilitates students to study at their own speed, and further organize students for future by providing real-world skills (Ustunel and Tokel 2018 ), that assist students to directly apply their academic skills, self-learning abilities, and of course computer know how into the working force (Güzer and Caner 2014 ; Yeou 2016 ). As pointed out by Al-shami et al. ( 2018 ) BL improves social communication in university’ communities, improves students’ aptitude and self-reliance, increased learning quality, improve critical thinking in learning setting and incorporate technology as an operative tool to convey course contents to students (Bailey et al. 2015 ; Baragash and Al-Samarraie 2018a ).

Existing studies mainly considered BL in the context of students and lecturers in improving teaching and learning. Prior studies paid attention to BL adoption towards improving the quality of student learning and lecturers teaching. But only fewer studies explored BL implementation process as well explored administrators’ who initiate policies related to BL adoption in higher education. To fill this gap in knowledge, this current study aims to systematically reviews and synthesizes prior studies that explored BL adoption and implementation related to students, lecturers and administration based on the following six research questions:

RQ1 What are the research methods, countries, contexts, and publication year of selected BL studies?

RQ2 Which BL studies proposed model related to BL adoption in higher education?

RQ3 Based on RQ2 what are the theories, location, and context of the selected BL studies?

RQ4 Based on RQ3 what are the constructs of the identified theories employed to explore BL adoption in higher education?

RQ5 What are the constructs and factors that influence students, lecturers and administration towards adopting BL?

RQ6 What are the practices involved for BL implementation in higher education?

Therefore, to address the research questions this study review and report on BL adoption model (constructs and factors), BL implementation processes, prior theories employed, and related studies that were mainly focused on BL adoption in relation to students, lecturers, and administrator’s perspective. The remainder of the article is organized as follows. Section 2 is the literature review. Section 3 is the methodology and Sect. 4 describes the findings and discussion. Section 5 is the implications and Sect. 6 is the conclusion, limitation, and future works.

2 Literature Review

Learning in higher education refers to process of acquiring new knowledge, skills, intellectual abilities which can be utilized to successfully solve problems. The deployment of technologies in teaching and learning is not a new paradigm in higher education (Poon 2012 ). Undeniably, in the twentyfirst century students are familiar with digital environments and therefore lecturers are encouraged to use Information Technology (IT) in teaching to stimulate and employ students’ learning (Ifenthaler and Widanapathirana 2014 ; Edward et al. 2018 ). Teaching and learning with the aid of BL practices have become a common teaching approach to involve students in learning (Garrison and Kanuka 2004 ). As such, BL has progressed to incorporate diverse learning strategies and is renowned as one of the foremost trends in higher education (Ramakrisnan et al. 2012 ). BL provides pedagogical productivity, knowledge access, collective collaborations, personal development, cost efficiency, simplifies corrections and further resolves problems related to attendance (Mustapa et al. 2015 ). Findings from prior studies (Wai and Seng 2015 ; Nguyen 2017 ) suggested that BL offers benefits and is also productive than traditional e-learning.

BL in higher education is a prevailing approach to create a more collaborative and welcoming learning environment to curb students' anxiety and fear of making mistakes (Wong et al. 2014 ). Adopted in universities in the late 1990s (Edward et al. 2018 ), it found wider acceptance in the 2000s with many more university courses offered in blended mode (Graham et al. 2013 ). BL employs a combination of online-mediated and face-to-face instruction to help lecturers attain pedagogical goals in training students to produce algorithmic and constructive rational skills, aids to enhance teaching qualities and achieve social order (Kaur 2013 ). Some researchers [such as Bowyer and Chambers ( 2017 )] argued that technology integration in teaching promotes learning via discovery. And adds interactivity and more motivation, leading to better feedback, social interactions, and use of course materials (Sun and Qiu 2017 ).

As seen in Fig. 1 , BL implementation usually involves F2F and other corresponding online learning delivery methods. Normally, students attend traditional lecturer-directed F2F classes with computer mediated tools to create a BL environment in gaining experiences and also promote learners’ learning success and engagement (Moskal et al. 2013 ; Baragash and Al-Samarraie 2018b ). In fact, Graham ( 2013 ); Graham et al. ( 2013 ) projected that BL will become the new course delivery model that employs different media resources to strengthen the interaction among students. BL provide motivating and meaningful learning through different asynchronous and synchronous teaching strategies such as forums, social networking, live chats, webinars, blog, etc. that provides more opportunities for reflection and feedback from students (Graham 2013 ; Moskal et al. 2013 ; Dakduk et al. 2018 ).

Key aspects of BL derived from (Graham 2013 ; Moskal et al. 2013 )

BL is facilitated with virtual learning management systems such as Blackboard WebCT, Moodle, and other Web 2.0 platforms which are employed to facilitate collaborative learning between students and lecturers (Edward et al. 2018 ; Anthony et al. 2019 ). Accordingly, Aguti et al. ( 2014 ) stated that 80 percent of institutions in developed regions dynamically employ BL approach to support teaching and learning, with 97 percent of institutions reported to be deploying one or more forms of IT mediated learning. Figure 1 indicates that BL instructional design and type of delivery includes online activities such as wordbook, reading materials, online writing tool, message board, web links, tutorials, discussion forum, reference material, simulations, quizzes, etc. (Anthony et al. 2019 ). Conversely, F2F teaching involves lectures, laboratory activities, assessment skill practices, presentation, individual/group, and discussions carried out by the lecturer to examine the learning performance of students (Sun and Qiu 2017 ).

There has been rapid development in BL adoption focused on improving teaching and learning outcome, thus prior studies assessed the effectiveness of BL by comparing the traditional teaching and online teaching (Van Laer and Elen 2020 ). However, there are limited studies that investigated the theoretical foundation of BL adoption and implementation for teaching and learning (Wai and Seng 2015 ), and very limited studies focused on investigating administrative adoption related to BL. To this end, Garrison and Kanuka ( 2004 ) mentioned that it is important to examine BL adoption from the lens of institutions administrators. Researchers such as Wong et al. ( 2014 ) argued that while there are studies in BL, research that focused on BL adoption and implementation are limited, and that this is a gap to be addressed. Given the above insights, it is felt that more BL based research is needed to guide policy makers to strategically adopt BL in higher education towards improving learning and teaching. Therefore, this study systematically reviews and synthesizes prior studies that explored students, lecturers and administration adoption and implementation of BL.

3 Methodology

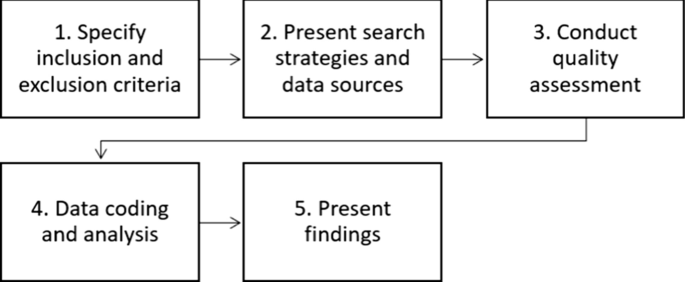

It is important to carry out an extensive literature review before starting any research investigation (Anthony et al. 2017a ). Literature review finds research gaps that exists and reveals areas where prior studies has not fully explored (Anthony et al. 2017b ). Likewise, a systematic literature review is a review that is based on unambiguous research questions, defines and explores pertinent studies, and lastly assesses the quality of the studies based on specified criteria (Al-Emran et al. 2018 ). Accordingly, this study followed the recommendation postulated by Kitchenham and Charters’s ( 2007 ) in reporting a systematic review. Therefore, the research design for this study comprises of five phases which includes the specification of inclusion and exclusion criteria, presenting of search strategies and data sources, quality assessment, and data coding and analysis, and lastly findings. The research design of this review study is shown in Fig. 2 .

Research design for SLR

Figure 2 depicts the research design for this study, where each phase is presented in the subsequent sub-sections.

3.1 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1 ) and quality assessment criteria (see Table 2 ) are employed as the sampling/selection methods used to select the articles involved in this study. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are defined in Table 1 .

3.2 Search Strategies and Data Sources

The articles involved in this study were retrieved through a comprehensive search of prior studies via online databases which included Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, Emerald, IEEE, Sage, Taylor & Francis, Inderscience, Springer, and Wiley. The search was undertaken in December 2018 and March 2020. The search terms comprise the keywords ((“blended learning practices” OR “blended learning variables” OR “blended learning factors” OR “blended learning constructs”) AND (“implementation” OR “adoption” OR “approach” OR “model” OR “framework” OR “theory”)) AND (“components” OR “elements”)). The mixture of the keywords is a crucial step in any systematic review as it defines articles that will be retrieved.

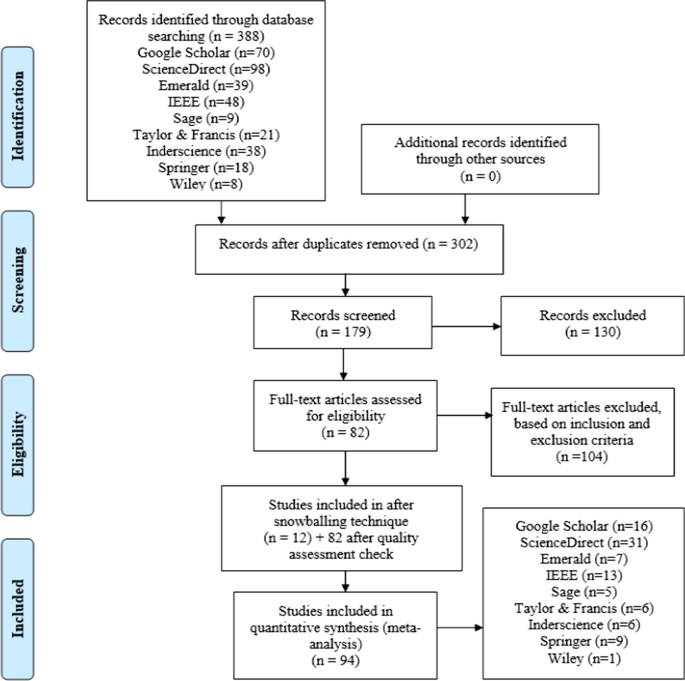

Figure 3 depicts the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) flowchart which was employed for searching and refining of the articles as previously utilized by Al-Emran et al. ( 2018 ). The search output presented 388 articles using the above stated keywords. 93 articles were establish as duplicates, as such were removed. Therefore, resulted to 302 articles. The authors checked the articles against the inclusion and exclusion criteria and added 12 new articles based on snowballing techniques which was used to get more articles from the references of 82 studies. Accordingly, 94 research articles meet the inclusion criteria and were included in the review process. Additionally, four studies (Kitchenham and Charters 2007 ; Anthony et al. 2017 , b ; Al-Emran et al. 2018 ) were included in the reference since they discuss SLR process.

PRISMA flowchart for the selected articles

3.3 Quality Assessment

One of the vital determinants that are required to be checked along with the inclusion and exclusion criteria is the quality assessment. To this end, a quality assessment checklist which comprises of “10” criteria was designed and employed as a means for evaluating the quality of the studies selected (n = 94) (see Fig. 3 ). The quality assessment checklist is shown in Table 2 . The checklist was adapted from recommendation from (Kitchenham and Charters 2007 ). Accordingly, the question was measured based on a 3-point scale which ranges from, 1 point being assigned for “Yes”, 0 point for “No”, and 0.5 point for “Partially”. Hence, each article score ranges from 0 to 10, where a study that attains higher total score, possess the capability to provide addresses the specified research questions. Table 11 in appendix shows the quality assessment results for all the 94 studies. Respectively, it is apparent that the selected studies have passed the quality assessment, which indicates that all the articles are eligible to be utilized for further meta-analysis.

3.4 Data Coding and Analysis

The characteristics related to the research methodology outcome were coded to include purpose of research, (BL adoption constructs and factors or BL implementation practice), research approach (e.g., literature review, conceptual, survey questionnaire, case study interviews, or experimental), country, context (e.g., student, lecturer and/or administrator), and model/framework or theory employed (e.g., Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), information system success model, the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), Diffusion of Innovations theory (DoI), Adhoc, etc.). In between the data analysis procedure, the articles that did not directly describe BL adoption model variables and implementation practices were excluded from the synthesis.

4 Findings and Discussion

Based on the selected 94 studies published in regard to BL adoption and implementation from 2004 to 2020, this review reports the findings of this systematic review in relation to the specified six research questions.

4.1 RQ1: What are the Research Methods, Countries, Contexts, and Publication Year of Selected BL Studies?

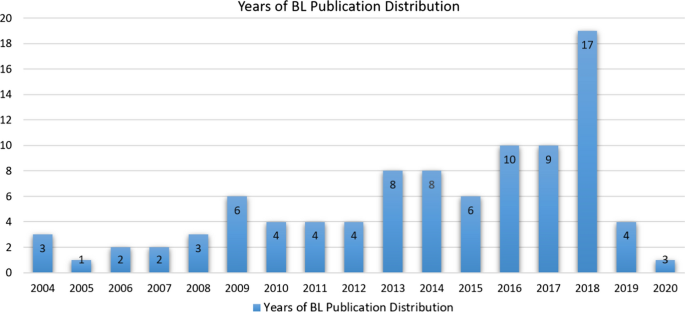

With regard to the first research question, the findings for distribution of studies related to BL adoption and implementation in higher education based on year of publication is presented in Fig. 4 . As shown, the studies are ranged from 2004 to 2020. Findings from Fig. 4 indicate that there seems to be an increase in studies on BL over the last few years as seen from 2004 to 2020, with 2018 being the highest with publications on BL adoption and implementation with 17 studies published. It is evident that the frequency of these publications in 2018 could be accredited to the fact that the intensity of BL implementation in 2018 across higher education has improved mainly in developed and developing countries across the world.

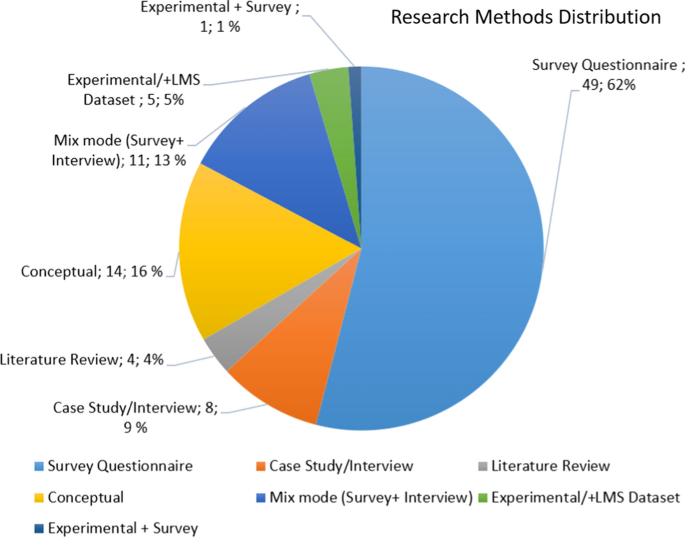

Distribution of selected BL studies in terms of years

Considering the research methodology applied in the 94 BL studies, findings from Fig. 5 show that questionnaire survey is the most employed method for data collection (N = 49, 62%), followed by studies that were conceptual by design with (N = 14, 16%). Next, is studies that adopted mixed method both survey and interview with (N = 11, 13%) and studies that are qualitative in nature as case study/interview with (N = 8, 9%). For the remaining studies (N = 5, 5%) employed experimental using LMS dataset, (N = 4, 4%) conducted literature review, and lastly only (N = 1, 1%) study deployed a mixed experimental and survey approach. These findings are analogous with the prior review studies conducted by (Holton III et al. 2006 ; Kumara and Pande 2017 ) who discussed that quantitative studies were the main approach employed in prior BL studies. Furthermore, this finding is consistent with the fact that surveys are considered as the most suitable tool to collect data in validating constructs/factors in developed BL adoption model in investigating students and lecturers’ perceptions towards BL practice in higher education (Ghazali et al. 2018 ; Ismail et al. 2018b ).

Distribution of selected BL studies in terms of research methods

With regard to the 94 BL studies country distribution, findings from Fig. 6 shows research related to BL adoption in higher education. Accordingly, most of the studies are conducted in Malaysia (N = 28), this is based on the fact that the Malaysia ministry of education initiated an educational blueprint for all higher education to adopt BL from 2015 to 2022. Therefore, there were several studies that proposed models to examine BL adoption in universities in Malaysia context. Next, research articles related to BL adoption was carried out in United States of America with (N = 11), and Australia (N = 10) and United Kingdom with (N = 7), followed by Turkey with (N = 4), Canada, Indonesia, and Spain with (N = 3) respectively. Additionally, Fig. 6 indicates that (N = 2) studies were conducted in Norway, Dubai, UAE, India, Singapore, Saudi Arabia, and Taiwan. Lastly, (N = 1) study was each conducted in Greece, Germany, Philippines, South Korea, The Netherlands, Thailand, Vietnam, Belgium, Bulgaria, China, Poland, Israel, Morocco, Colombia, Sri Lanka, and Ghana. This finding also suggest that most of the first researchers of BL adoption such as Garrison and Kanuka ( 2004 ), Graham et al. ( 2013 ), Poon ( 2014 ) and Porter and Graham ( 2016 ) are from USA, Canada, Australia and UK who are one of the most cited researchers in BL practice in higher education as compared to other regions.

Distribution of selected BL studies in terms of countries

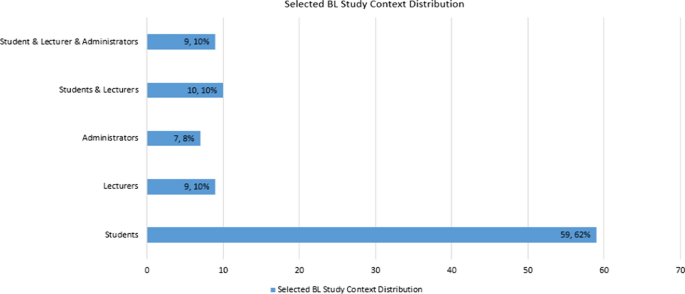

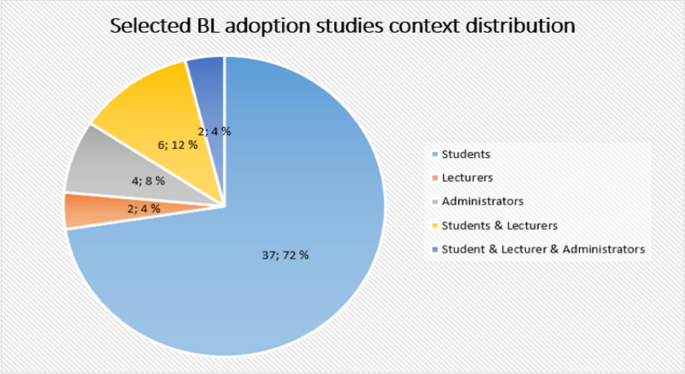

Considering the selected studies context distribution of BL adoption in higher education findings from Fig. 7 indicate that (N = 59, 62%) studies mainly examined BL adoption by considering students perspective. This finding is consistent with results from prior studies (Wai and Seng 2013; Rahman et al. 2015 ) which advocated for the need for developing a model of measuring student satisfaction, perception (So and Brush 2008 ), commitment (Wong et al. 2014 ), effectiveness (Wai and Seng 2015 ) in the BL. In addition, findings from Fig. 7 reveal that (N = 9, 10%) studies mainly examined BL adoption by considering lecturers perspective. This finding is very consistent with results from the literature (Wong et al. 2014 ; Zhu et al. 2016 ), where the authors mentioned the need for a study to investigate the current level of adoption of BL among the academicians to identify the factors that influence BL adoption.

Distribution of selected BL studies context

Furthermore, the findings suggest that (N = 7, 8%) studies mainly examined BL adoption by considering administrative perspective. Similarly, this finding is analogous with results from qualitative studies conducted by prior researchers (Koohang, 2008 ; Graham et al. 2013 ; Porter et al. 2016 ; Bokolo Jr et al. 2020 ) which revealed that there are limited studies that explored policy and governance issues related BL adoption. Additionally, findings from Fig. 7 show that (N = 10, 10%) studies that concurrently examined BL in the context of students and lecturers, this aligns with findings presented by Brahim and Mohamad ( 2018 ); Edward et al. ( 2018 ) where the authors called for the need for empirical evidence on BL implementation to improve academic activities. Lastly, (N = 9, 10%) studies investigated BL in the context of student, lecturer, and administrators. This finding suggests that there are limited studies that examine students, lectures and administrators simultaneously as mentioned by (Machado 2007 ; Wong et al. 2014 ; Bokolo Jr et al. 2020 ). Accordingly, this review presents the constructs and factors that influence BL adoption from the perspective of students, lecturers, and administrators in higher education.

4.2 RQ2: Which BL Studies Proposed Model Related to BL Adoption in Higher Education?

Several studies have been carried out directed towards investigating the adoption of BL in higher education. Thus, Table 3 shows that out of the selected 94 studies only 51 studies developed models to examine BL where each study is compared based on the authors, contribution, purpose and identified factors/attributes and methods.

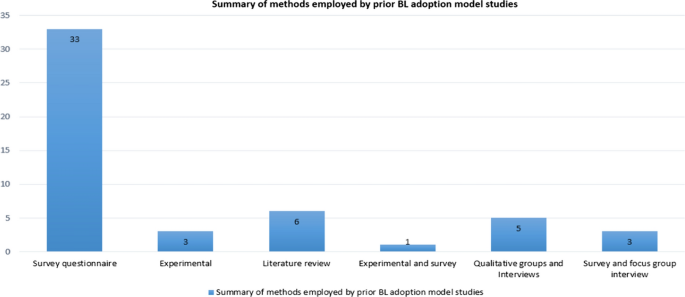

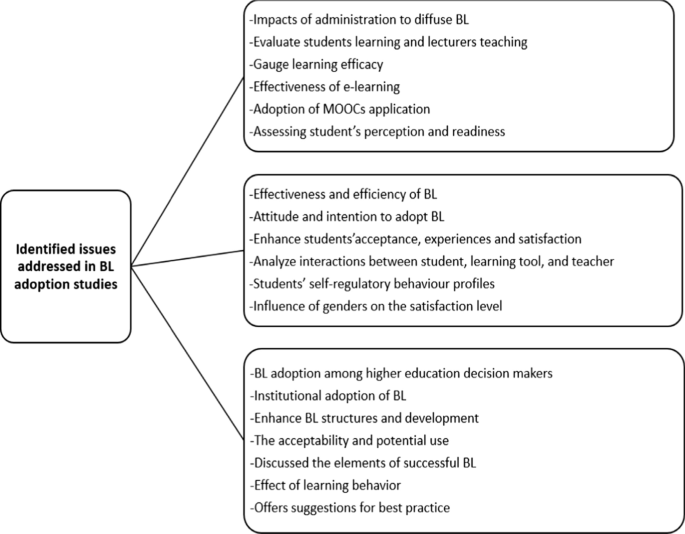

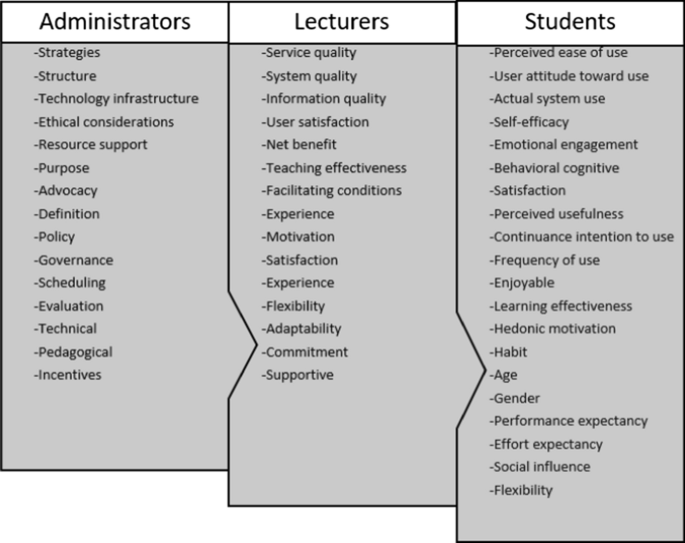

Based on the selected 51 BL studies that develop a research model to examine BL adoption in higher education, the review indicates that none of the studies is concerned with BL practices to be implemented in higher education, they are mainly concerned about BL adoption factors/attributes. As seen in Fig. 8 out of the reviewed 51 BL studies that developed models to examine BL adoption. The results suggest that survey questionnaire was most employed, whereas experimental and survey was least employed to validate the developed models. Also, Fig. 9 presents the clustered of issues addressed in the reviewed 51 BL studies. The identified factors/attributes derived from the reviewed 51 BL studies are presented in Fig. 10 and further discussed in Tables 6 , 7 and 8 .

Distribution of the reviewed 51 BL studies that developed BL adoption models

Clustering of issues addressed in the reviewed BL adoption studies

Identified factors/attributes derived in the reviewed BL adoption studies

4.3 RQ3: Based on RQ2 What are the Theories, Location, and Context of the Selected BL Studies?

Among the selected 51 BL studies, this sub-section presents prior theories that have been utilized to examine BL adoption in higher education. Moreover, the location and BL context of the 51 BL studies are presented as seen in Table 4 .

Findings from Table 4 and Fig. 11 indicate that out of the reviewed 51 BL studies, (N = 37, 72%) studies investigated BL by considering the students context similar to previous studies Tuparova and Tuparov ( 2011 ); Roszak et al. ( 2014 ), while (N = 2, 4%) studies examined BL by considering only lecturers’ context. Besides, (N = 4, 8%) studies only examined administration context analogous with prior study Mercado ( 2008 ), while another (N = 6, 12%) studies examined BL by considering the students and lecturers context similar to prior studies Maulan and Ibrahim ( 2012 ); Mohd et al. ( 2016 ). Lastly, (N = 2, 4%) studies examined BL by considering the students, lecturers and administration context analogous to research conducted by Mercado ( 2008 ); Anthony et al. ( 2019 ). Hence, it is evident that there are fewer studies that investigated BL adoption by concurrently exploring students, lecturers and administration viewpoint. Thus, this review aims to address this limitation by reviewing theoretical foundation of BL adoption and implementation in the lens of students, lecturers and administration.

Selected BL adoption studies context distribution

4.4 RQ4: Based on RQ3 What are the Constructs of the Identified Theories Employed to Explore BL Adoption in Higher Education?

This sub-section reviews the constructs of theories employed by the selected 51 BL studies in developing their model as seen in Table 5 .

Based on Tables 4 and 5 , Fig. 12 depicts the frequency of how many times each theory has been employed by prior BL studies. Findings from theories employed show that ad hoc is the most employed approach with (N = 23, 42%) studies, followed by TAM with (N = 7, 13%) studies, IS success model and UTAUT with (N = 4, 7%) studies individually, and DoI with (N = 3, 5%) studies, whereas the other theories were adopted by (N = 1, 2%) study respectively.

Distribution of BL studies in terms of adopted theories

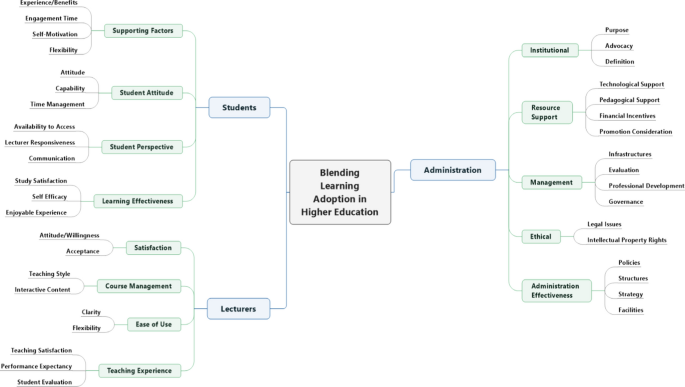

4.5 RQ5: What are the Constructs and Factors that Influence Students, Lecturers and Administration towards Adopting BL?

The constructs and factors related to the adoption of BL by students, lecturers and administrators are shown in Fig. 13 and described in Table 6 .

Constructs and factors related to BL adoption in higher education

Tables 6 , 7 and 8 describes the derived constructs for students, lecturers, and administration related to BL adoption in higher education. BL adoption cannot be attained by only integrating online and face-to-face teaching modes (Azizan 2010 ). Thus, there is need to identify the constructs that influence students, lecturer, and administration in adopting BL practices to be implemented that play an important role in ensuring successful BL experience in higher education (Graham 2013 ; Güzer and Caner 2014 ). On this note, academicians such as Machado ( 2007 ); Wong et al. ( 2014 ); Kumara and Pande ( 2017 ); Bokolo Jr et al. ( 2020 ) highlighted that successful implementation of BL initiatives requires an alignment between administrative, lecturers, students’ educational goals. According to Dakduk et al. ( 2018 ); Anthony et al. ( 2019 ) it is importance to examine constructs related to human computer interaction to assess which constructs contributes to realizing the desired teaching and learning objectives while engaging the lecturers and students. Therefore, this study explores the BL practices to be implemented by students and lecturers in higher education as seen in Figs. 14 and 15 .

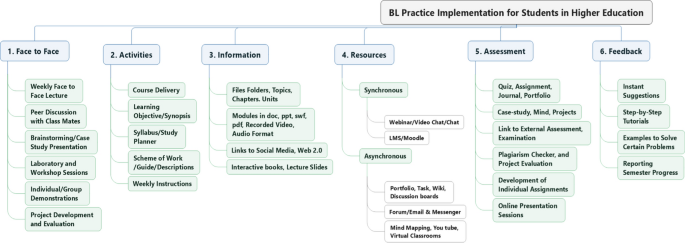

BL practice implementation for students in higher education

BL practice implementation for lecturers in higher education

4.6 RQ6: What are the Practices Involved for BL Implementation in Higher Education?

The practice to be carried out by students for implementing BL in higher education is shown in Fig. 14 .

Figure 14 depicts BL practice implementation for students in higher education. According to Kaur and Ahmed ( 2006 ); Kaur ( 2013 ) the recommended balance of BL activities for successful delivery is 80% online learning (activities, information, resources, assessment and feedback) followed by 20% classroom instruction (face to face) that is aligned to the online teaching content. Similarly, Ginns and Ellis ( 2007 ) argued that for an effective BL initiative it is required to achieve a blend of 29–30% face to face and 79–80% on-line teaching delivery. This is in line with findings from previous studies (Graham et al. 2013 ; Bokolo Jr et al. 2020 ), which states that there is need for policies showing clear decrease of face to face classroom hours and increasing online learning as a strategy to enhance BL implementation in higher education (Park et al. 2016 ). Further description of BL implementation for students is discussed in Table 9 .

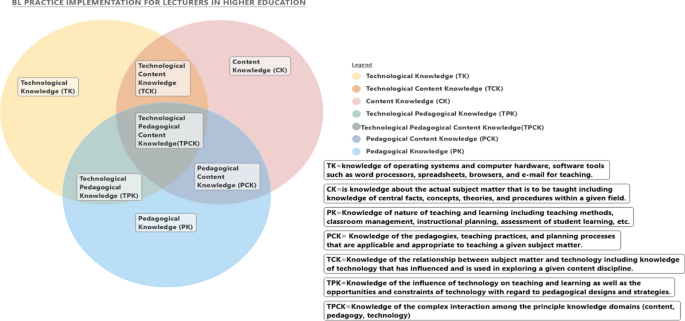

Figure 15 depicts BL practice implementation for lecturers in higher education. The BL practice is based on the Technology, Pedagogy, and Content Knowledge (TPACK) framework proposed by Koehler and Mishra ( 2009 ). TPACK aimed address issues faced by how lecturers can integrate technology into their current teaching (Wang et al. 2004 ; Sahin 2011 ). Thus, TPACK offers a method that indulgences teaching as collaboration between what lecturers know and how they teach and apply what they already know uniquely through BL implementation in the contexts of physical and online classes (Graham et al. 2009 ; Koehler and Mishra 2009 ). Further description of TPACK the components in relation to BL implementation is discussed in Table 10 .

5 Implications for Theory, Methodology and Pedagogical Practice

Findings from this study offer implications for theory, methodology and pedagogical practice for higher education towards adopting BL.

5.1 Implications for Theory

Theoretically, this study identifies the factors that influence students, lecturers and administrators’ towards adopting BL. Our findings provide insight by revealing factors for higher education to better recognize how BL can be delivered towards the development of students’ learning effectiveness and also offering in-depth understanding of BL and its efficiency in order to improve students’ competence. The identified factors can be employed by institutions to assess students, lecturers and administrators’ perception towards BL and can be used to inform government policy making regarding BL development. Besides, this study also indicates that the lecturer’s attitude, teaching style, and acceptance toward BL are important in motivating the students to adopt BL. The lecturer’s attitude toward students and his/her level of responsiveness and communication are important factors that motivate students in BL environment. The findings emphasized the importance of administrative commitment towards BL adoption, showing that the purpose, advocacy and definition initiated towards BL have a strong impact on both learning and teaching effectiveness. The findings provide theoretical support to determine the relationship among the constructs and factors of BL adoption for students, lecturers and administrators (see Fig. 13 ) towards F2F and online learning.

5.2 Implications for Methodology

Based on the TPACK framework, this study provides lecturers with understanding of students' perspective on BL in helping them to reflect on their role in improving their current pedagogy, technological infusion, and syllabus design to enhance student learning and teaching outcome. Decision makers in higher education can utilize findings from this study to improve their understanding of the factors that impacts students, lecturers and administrators’ perception towards BL adoption. Respectively, given the different perspectives of students, lecturers and administrators it is mandatory for policy makers in higher education involved in the implementation of BL to deliberate on the perspectives of all stakeholders. Respectively, findings from this study significantly provide an outline for Ministry of Education across the world towards fostering BL as a teaching and learning approach for academic staffs in higher education. The BL practices for students (see Fig. 14 ) and strategies to be implemented by lecturers (see Fig. 15 ) can be integrated to the existing pedagogical polices to improve the significance of BL as one of the methods in learning and teaching. For universities and academicians, findings from this study suggest that BL serves as a substitute to learning and teaching from the traditional perspective to enhance the quality of teaching and learning of students in achieving better performance.

5.3 Implications for Pedagogical Practice

This study contributes to the acknowledgment of BL as a medium to support teaching and learning approach. The findings describing how BL practice can be implemented by students as seen in Sect. 4.6 (Fig. 14 ). Practically, findings from this study can be useful in the preparation of the best practice to support lecturers in teaching and implementing inventive approaches that promotes BL to enhance teaching and learning outcomes to be used as the reference for the arranging methodologies to embrace BL in higher education. Findings from this study indicate that BL practices derived from the literature which comprises of face-to-face, activities, information, resources, assessment, and feedback to be deployed by educators to design suitable learning policies in order to support students towards improving learning. These findings provide guidelines on the design and implementation of BL practice. This study suggests that for BL practice to be successfully implemented the decision of lecturers are determined by the ease with which online course services are managed. Thus, the availability of computer hardware and software resources, pedagogical support, financial support, and promotion consideration should be provided by institutions management. For administrators this study provides a policy roadmap to adopt BL in higher education.

6 Conclusion, Limitations, and Future Works

Review of prior studies on BL offer valuable insight regarding research related to BL practice in higher education. Nonetheless, these review studies ignored examining BL adoption and implementation in regard to students, lecturers and administrators simultaneously. Accordingly, this study conducted a systematic literature review for prior BL adoption model proposed related to theories employed in the model to investigate BL adoption in higher education. This study also identified the constructs and factors that influence students, lecturers and administration towards adopting BL studies and lastly derived the practices involved for BL implementation for students and lecturers in higher education with the aim of providing meta-analysis of the current studies and to present the implications from the review. Respectively, this paper extends the body of knowledge in BL studies by presenting 7 new findings. First, the review reveal that ad hoc approach is the most employed method by prior studies in developing research model to investigate BL adoption in higher education, followed by TAM, and then IS success model, then is UTAUT, and lastly DoI theory.

Secondly, findings show that questionnaire surveys were the most employed research methods for data collection utilized by prior BL studies in higher education. Third, the findings reveal that BL model adoption studies were carry out in Malaysia and USA, this is followed by Australia, UK, Canada, respectively among the other countries. Fourth, most of the BL studies were recurrently conducted towards examining BL in students’ context, followed by lecturers’ context, correspondingly among the other contexts. Fifth, with regard to publication year, BL studies have experienced vast attraction over the years (2016 to 2019) from many academicians who contributed to investigating BL adoption and implementation in higher educational context, where our findings observed an increase of 19 publications in 2018 (see Fig. 4 ) representing the highest frequency of the total studies. Sixth, this review also presents 51 prior studies that developed model relating to the adoption of BL in higher educational domain and further identify the constructs/factors that influence the perception of students, lecturers, and administration readiness towards BL adoption. Seventh, findings from this review present the BL practice to be implemented by students and lecturers in higher education. To that end, the identified constructs/factors that influence BL adoption and the derived BL practices implementation can be used to conceptualize and develop a model to examine student, lecturers, and administrators concurrently towards BL adoption and implementation in higher education.