School of Writing, Literature, and Film

- BA in English

- BA in Creative Writing

- About Film Studies

- Film Faculty

- Minor in Film Studies

- Film Studies at Work

- Minor in English

- Minor in Writing

- Minor in Applied Journalism

- Scientific, Technical, and Professional Communication Certificate

- Academic Advising

- Student Resources

- Scholarships

- MA in English

- MFA in Creative Writing

- Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies (MAIS)

- Low Residency MFA in Creative Writing

- Undergraduate Course Descriptions

- Graduate Course Descriptions

- Faculty & Staff Directory

- Faculty by Fields of Focus

- Promoting Your Research

- 2024 Spring Newsletter

- Commitment to DEI

- Twitter News Feed

- 2022 Spring Newsletter

- OSU - University of Warsaw Faculty Exchange Program

- SWLF Media Channel

- Student Work

- View All Events

- The Stone Award

- Conference for Antiracist Teaching, Language and Assessment

- Continuing Education

- Alumni Notes

- Featured Alumni

- Donor Information

- Support SWLF

The CLA websites are currently under construction and may not reflect the most current information until the Fall Term.

What is Literature? || Definition & Examples

"what is literature": a literary guide for english students and teachers.

View the full series: The Oregon State Guide to English Literary Terms

- Guide to Literary Terms

- BA in English Degree

- BA in Creative Writing Degree

- Oregon State Admissions Info

What is Literature? Transcript (English and Spanish Subtitles Available in Video; Click HERE for Spanish Transcript)

By Evan Gottlieb & Paige Thomas

3 January 2022

The question of what makes something literary is an enduring one, and I don’t expect that we’ll answer it fully in this short video. Instead, I want to show you a few different ways that literary critics approach this question and then offer a short summary of the 3 big factors that we must consider when we ask the question ourselves.

Let’s begin by making a distinction between “Literature with a capital L” and “literature with a small l.”

“Literature with a small l” designates any written text: we can talk about “the literature” on any given subject without much difficulty.

“Literature with a capital L”, by contrast, designates a much smaller set of texts – a subset of all the texts that have been written.

what_is_literature_little_l.png

So what makes a text literary or what makes a text “Literature with a capital L”?

Let’s start with the word itself. “Literature” comes from Latin, and it originally meant “the use of letters” or “writing.” But when the word entered the Romance languages that derived from Latin, it took on the additional meaning of “knowledge acquired from reading or studying books.” So we might use this definition to understand “Literature with a Capital L” as writing that gives us knowledge--writing that should be studied.

But this begs the further question: what books or texts are worth studying or close reading ?

For some critics, answering this question is a matter of establishing canonicity. A work of literature becomes “canonical” when cultural institutions like schools or universities or prize committees classify it as a work of lasting artistic or cultural merit.

The canon, however, has proved problematic as a measure of what “Literature with a capital L” is because the gatekeepers of the Western canon have traditionally been White and male. It was only in the closing decades of the twentieth century that the canon of Literature was opened to a greater inclusion of diverse authors.

And here’s another problem with that definition: if inclusion in the canon were our only definition of Literature, then there could be no such thing as contemporary Literature, which, of course, has not yet stood the test of time.

And here’s an even bigger problem: not every book that receives good reviews or a wins a prize turns out to be of lasting value in the eyes of later readers.

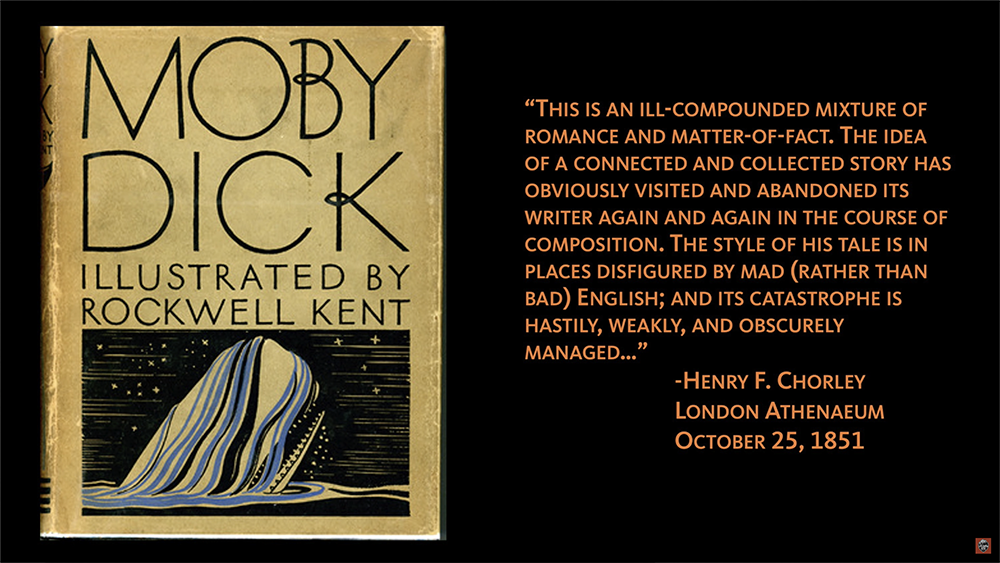

On the other hand, a novel like Herman Melville’s Moby-Di ck, which was NOT received well by critics or readers when it was first published in 1851, has since gone on to become a mainstay of the American literary canon.

moby_dick_with_quote.png

As you can see, canonicity is obviously a problematic index of literariness.

So… what’s the alternative? Well, we could just go with a descriptive definition: “if you love it, then it’s Literature!”

But that’s a little too subjective. For example, no matter how much you may love a certain book from your childhood (I love The Very Hungry Caterpillar ) that doesn’t automatically make it literary, no matter how many times you’ve re-read it.

Furthermore, the very idea that we should have an emotional attachment to the books we read has its own history that cannot be detached from the rise of the middle class and its politics of telling people how to behave.

Ok, so “literature with a capital L” cannot always by defined by its inclusion in the canon or the fact that it has been well-received so…what is it then? Well, for other critics, what makes something Literature would seem to be qualities within the text itself.

According to the critic Derek Attridge, there are three qualities that define modern Western Literature:

1. a quality of invention or inventiveness in the text itself;

2. the reader’s sense that what they are reading is singular. In other words, the unique vision of the writer herself.

3. a sense of ‘otherness’ that pushes the reader to see the world around them in a new way

Notice that nowhere in this three-part definition is there any limitation on the content of Literature. Instead, we call something Literature when it affects the reader at the level of style and construction rather than substance.

In other words, Literature can be about anything!

what_is_literature_caterpillar.png

The idea that a truly literary text can change a reader is of course older than this modern definition. In the English tradition, poetry was preferred over novels because it was thought to create mature and sympathetic reader-citizens.

Likewise, in the Victorian era, it was argued that reading so-called “great” works of literature was the best way for readers to realize their full spiritual potentials in an increasingly secular world.

But these never tell us precisely what “the best” is. To make matters worse, as I mentioned already, “the best” in these older definitions was often determined by White men in positions of cultural and economic power.

So we are still faced with the question of whether there is something inherent in a text that makes it literary.

Some critics have suggested that a sense of irony – or, more broadly, a sense that there is more than one meaning to a given set of words – is essential to “Literature with a capital L.”

Reading for irony means reading slowly or at least attentively. It demands a certain attention to the complexity of the language on the page, whether that language is objectively difficult or not.

In a similar vein, other critics have claimed that the overall effect of a literary text should be one of “defamiliarization,” meaning that the text asks or even forces readers to see the world differently than they did before reading it.

Along these lines, literary theorist Roland Barthes maintained that there were two kinds of texts: the text of pleasure, which we can align with everyday Literature with a small l” and the text of jouissance , (yes, I said jouissance) which we can align with Literature. Jouissance makes more demands on the reader and raises feelings of strangeness and wonder that surpass the everyday and even border on the painful or disorienting.

Barthes’ definition straddles the line between objectivity and subjectivity. Literature differs from the mass of writing by offering more and different kinds of experiences than the ordinary, non-literary text.

Literature for Barthes is thus neither entirely in the eye of the beholder, nor something that can be reduced to set of repeatable, purely intrinsic characteristics.

This negative definition has its own problems, though. If the literary text is always supposed to be innovative and unconventional, then genre fiction, which IS conventional, can never be literary.

So it seems that whatever hard and fast definition we attempt to apply to Literature, we find that we run up against inevitable exceptions to the rules.

As we examine the many problematic ways that people have defined literature, one thing does become clear. In each of the above examples, what counts as Literature depends upon three interrelated factors: the world, the text, and the critic or reader.

You see, when we encounter a literary text, we usually do so through a field of expectations that includes what we’ve heard about the text or author in question [the world], the way the text is presented to us [the text], and how receptive we as readers are to the text’s demands [the reader].

With this in mind, let’s return to where we started. There is probably still something to be said in favor of the “test of time” theory of Literature.

After all, only a small percentage of what is published today will continue to be read 10, 20, or even 100 years from now; and while the mechanisms that determine the longevity of a text are hardly neutral, one can still hope that individual readers have at least some power to decide what will stay in print and develop broader cultural relevance.

The only way to experience what Literature is, then, is to keep reading: as long as there are avid readers, there will be literary texts – past, present, and future – that challenge, excite, and inspire us.

Want to cite this?

MLA Citation: Gottlieb, Evan and Paige Thomas. "What is Literature?" Oregon State Guide to English Literary Terms, 3 Jan. 2022, Oregon State University, https://liberalarts.oregonstate.edu/wlf/what-literature-definition-examples. Accessed [insert date].

Interested in more video lessons? View the full series:

The oregon state guide to english literary terms, contact info.

Email: [email protected]

College of Liberal Arts Student Services 214 Bexell Hall 541-737-0561

Deans Office 200 Bexell Hall 541-737-4582

Corvallis, OR 97331-8600

liberalartsosu liberalartsosu liberalartsosu liberalartsosu CLA LinkedIn

- Dean's Office

- Faculty & Staff Resources

- Research Support

- Featured Stories

- Undergraduate Students

- Transfer Students

- Graduate Students

- Career Services

- Internships

- Financial Aid

- Honors Student Profiles

- Degrees and Programs

- Centers and Initiatives

- School of Communication

- School of History, Philosophy and Religion

- School of Language, Culture and Society

- School of Psychological Science

- School of Public Policy

- School of Visual, Performing and Design Arts

- School of Writing, Literature and Film

- Give to CLA

Literary Genres: Definition and Examples of the 4 Essential Genres and 100+ Subgenres

by Joe Bunting | 1 comment

What are literary genres? Do they actually matter to readers? How about to writers? What types of literary genres exist? And if you're a writer, how do you decide which genre to write in?

To begin to think about literary genres, let's start with an example.

Let's say want to read something. You go to a bookstore or hop onto a store online or go to a library.

But instead of a nice person wearing reading glasses and a cardigan asking you what books you like and then thinking through every book ever written to find you the next perfect read (if that person existed, for the record, they would be my favorite person), you're faced with this: rows and rows of books with labels on the shelves like “Literary Fiction,” “Travel,” “Reference,” “Science Fiction,” and so on.

You stop at the edge of the bookstore and just stand there for a while, stumped. “What do all of these labels even mean?!” And then you walk out of the store.

Or maybe you're writing a book , and someone asks you a question like this: “What kind of book are you writing? What genre is it?”

And you stare at them in frustration thinking, “My book transcends genre, convention, and even reality, obviously. Don't you dare put my genius in a box!”

What are literary genres? In this article, we'll share the definition and different types of literary genres (there are four main ones but thousands of subgenres). Then, we'll talk about why genre matters to both readers and writers. We'll look at some of the components that people use to categorize writing into genres. Finally, we'll give you a chance to put genre into practice with an exercise .

Table of Contents

Introduction Literary Genres Definition Why Genre Matters (to Readers, to Writers) The 4 Essential Genres 100+ Genres and Subgenres The 7 Components of Genre Practice Exercise

Ready to get started? Let's get into it.

What Are Literary Genres? Literary Genre Definition

Let's begin with a basic definition of literary genres:

Literary genres are categories, types, or collections of literature. They often share characteristics, such as their subject matter or topic, style, form, purpose, or audience.

That's our formal definition. But here's a simpler way of thinking about it:

Genre is a way of categorizing readers' tastes.

That's a good basic definition of genre. But does genre really matter?

Why Literary Genres Matter

Literary genres matter. They matter to readers but they also matter to writers. Here's why:

Why Literary Genres Matter to Readers

Think about it. You like to read (or watch) different things than your parents.

You probably also like to read different things at different times of the day. For example, maybe you read the news in the morning, listen to an audiobook of a nonfiction book related to your studies or career in the afternoon, and read a novel or watch a TV show in the evening.

Even more, you probably read different things now than you did as a child or than you will want to read twenty years from now.

Everyone has different tastes.

Genre is one way we match what readers want to what writers want to write and what publishers are publishing.

It's also not a new thing. We've been categorizing literature like this for thousands of years. Some of the oldest forms of writing, including religious texts, were tied directly into this idea of genre.

For example, forty percent of the Old Testament in the Bible is actually poetry, one of the four essential literary genres. Much of the New Testament is in the form of epistle, a subgenre that's basically a public letter.

Genre matters, and by understanding how genre works, you not only can find more things you want to read, you can also better understand what the writer (or publisher) is trying to do.

Why Literary Genres Matter to Writers

Genre isn't just important to readers. It's extremely important to writers too.

In the same way the literary genres better help readers find things they want to read and better understand a writer's intentions, genres inform writers of readers' expectations and also help writers find an audience.

If you know that there are a lot of readers of satirical political punditry (e.g. The Onion ), then you can write more of that kind of writing and thus find more readers and hopefully make more money. Genre can help you find an audience.

At the same time, great writers have always played with and pressed the boundaries of genre, sometimes even subverting it for the sake of their art.

Another way to think about genre is a set of expectations from the reader. While it's important to meet some of those expectations, if you meet too many, the reader will get bored and feel like they know exactly what's going to happen next. So great writers will always play to the readers' expectations and then change a few things completely to give readers a sense of novelty in the midst of familiarity.

This is not unique to writers, by the way. The great apparel designer Virgil Abloh, who was an artistic director at Louis Vuitton until he passed away tragically in 2021, had a creative template called the “3% Rule,” where he would take an existing design, like a pair of Nike Air Jordans, and make a three percent change to it, transforming it into something completely new. His designs were incredibly successful, often selling for thousands of dollars.

This process of taking something familiar and turning it into something new with a slight change is something artists have done throughout history, including writers, and it's a great way to think about how to use genre for your own writing.

What Literary Genre is NOT: Story Type vs. Literary Genres

Before we talk more about the types of genre, let's discuss what genre is not .

Genre is not the same as story type (or for nonfiction, types of nonfiction structure). There are ten (or so) types of stories, including adventure, love story, mystery, and coming of age, but there are hundreds, even thousands of genres.

Story type and nonfiction book structure are about how the work is structured.

Genre is about how the work is perceived and marketed.

These are related but not the same.

For example, one popular subgenre of literature is science fiction. Probably the most common type of science fiction story is adventure, but you can also have mystery sci-fi stories, love story sci-fi, and even morality sci-fi. Story type transcends genre.

You can learn more about this in my book The Write Structure , which teaches writers the simple process to structure great stories. Click to check out The Write Structure .

This is true for non-fiction as well in different ways. More on this in my post on the seven types of nonfiction books .

Now that we've addressed why genre matters and what genre doesn't include, let's get into the different literary genres that exist (there are a lot of them!).

How Many Literary Genres Are There? The 4 Essential Genres, and 100+ Genres and Subgenres

Just as everyone has different tastes, so there are genres to fit every kind of specific reader.

There are four essential literary genres, and all are driven by essential questions. Then, within each of those essential genres are genres and subgenres. We will look at all of these in turn, below, as well as several examples of each.

An important note: There are individual works that fit within the gaps of these four essential genres or even cross over into multiple genres.

As with anything, the edges of these categories can become blurry, for example narrative poetry or fictional reference books.

A general rule: You know it when you see it (except, of course, when the author is trying to trick you!).

1. Nonfiction: Is it true?

The core question for nonfiction is, “Is it true?”

Nonfiction deals with facts, instruction, opinion/argument reference, narrative nonfiction, or a combination.

A few examples of nonfiction (more below): reference, news, memoir, manuals, religious inspirational books, self-help, business, and many more.

2. Fiction: Is it, at some level, imagined?

The core question for fiction is, “Is it, at some level, imagined?”

Fiction is almost always story or narrative. However, satire is a form of “fiction” that's structured like nonfiction opinion/essays or news. And one of the biggest insults you can give to a journalist, reporter, or academic researcher is to suggest that their work is “fiction.”

3. Drama: Is it performed?

Drama is a genre of literature that has some kind of performance component. This includes theater, film, and audio plays.

The core question that defines drama is, “Is it performed?”

As always, there are genres within this essential genre, including horror films, thrillers, true crime podcasts, and more.

4. Poetry: Is it verse?

Poetry is in some ways the most challenging literary genre to define because while poetry is usually based on form, i.e. lines intentionally broken into verse, sometimes including rhyme or other poetic devices, there are some “poems” that are written completely in prose called prose poetry. These are only considered poems because the author and/or literary scholars said they were poems.

To confuse things even more, you also have narrative poetry, which combines fiction and poetry, and song which combines poetry and performance (or drama) with music.

Which is all to say, poetry is challenging to classify, but again, you usually know it when you see it.

Next, let's talk about the genres and subgenres within those four essential literary genres.

The 100+ Literary Genres and Subgenres with Definitions

Genre is, at its core, subjective. It's literally based on the tastes of readers, tastes that change over time, within markets, and across cultures.

Thus, there are essentially an infinite number of genres.

Even more, genres are constantly shifting. What is considered contemporary fiction today will change a decade from now.

So take the lists below (and any list of genres you see) as an incomplete, likely outdated, small sample size of genre with definitions.

1. Fiction Genres

Sorted alphabetically.

Action/Adventure. An action/adventure story has adventure elements in its plot line. This type of story often involves some kind of conflict between good and evil, and features characters who must overcome obstacles to achieve their goals .

Chick Lit. Chick Lit stories are usually written for women who interested in lighthearted stories that still have some depth. They often include romance, humor, and drama in their plots.

Comedy. This typically refers to historical stories and plays (e.g. Shakespeare, Greek Literature, etc) that contain a happy ending, often with a wedding.

Commercial. Commercial stories have been written for the sole purpose of making money, often in an attempt to cash in on the success of another book, film, or genre.

Crime/Police/Detective Fiction. Crime and police stories feature a detective, whether amateur or professional, who solves crimes using their wits and knowledge of criminal psychology.

Drama or Tragedy. This typically refers to historical stories or plays (e.g. Shakespeare, Greek Literature, etc) that contain a sad or tragic ending, often with one or more deaths.

Erotica. Erotic stories contain explicit sexual descriptions in their narratives.

Espionage. Espionage stories focus on international intrigue, usually involving governments, spies, secret agents, and/or terrorist organizations. They often involve political conflict, military action, sabotage, terrorism, assassination, kidnapping, and other forms of covert operations.

Family Saga. Family sagas focus on the lives of an extended family, sometimes over several generations. Rather than having an individual protagonist, the family saga tells the stories of multiple main characters or of the family as a whole.

Fantasy. Fantasy stories are set in imaginary worlds that often feature magic, mythical creatures, and fantastic elements. They may be based on mythology, folklore, religion, legend, history, or science fiction.

General Fiction. General fiction novels are those that deal with individuals and relationships in an ordinary setting. They may be set in any time period, but usually take place in modern times.

Graphic Novel. Graphic novels are a hybrid between comics and prose fiction that often includes elements of both.

Historical Fiction. Historical stories are written about imagined or actual events that occurred in history. They usually take place during specific periods of time and often include real or imaginary characters who lived at those times.

Horror Genre. Horror stories focus on the psychological terror experienced by their characters. They often feature supernatural elements, such as ghosts, vampires, werewolves, zombies, demons, monsters, and aliens.

Humor/Satire. This category includes stories that have been written using satire or contain comedic elements. Satirical novels tend to focus on some aspect of society in a critical way.

LGBTQ+. LGBTQ+ novels are those that feature characters who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, or otherwise non-heterosexual.

Literary Fiction. Literary fiction novels or stories have a high degree of artistic merit, a unique or experimental style of writing , and often deal with serious themes.

Military. Military stories deal with war, conflict, combat, or similar themes and often have strong action elements. They may be set in a contemporary or a historical period.

Multicultural. Multicultural stories are written by and about people who have different cultural backgrounds, including those that may be considered ethnic minorities.

Mystery G enre. Mystery stories feature an investigation into a crime.

Offbeat/Quirky. An offbeat story has an unusual plot, characters, setting, style, tone, or point of view. Quirkiness can be found in any aspect of a story, but often comes into play when the author uses unexpected settings, time periods, or characters.

Picture Book. Picture book novels are usually written for children and feature simple plots and colorful illustrations . They often have a moral or educational purpose.

Religious/Inspirational. Religious/ inspirational stories describe events in the life of a person who was inspired by God or another supernatural being to do something extraordinary. They usually have a moral lesson at their core.

Romance Genre. Romance novels or stories are those that focus on love between two people, often in an ideal setting. There are many subgenres in romance, including historical, contemporary, paranormal, and others.

Science Fiction. Science fiction stories are usually set in an imaginary future world, often involving advanced technology. They may be based on scientific facts but they are not always.

Short Story Collection . Short story collections contain several short stories written by the same or different authors.

Suspense or Thriller Genre. Thrillers/ suspense stories are usually about people in danger, often involving crimes, natural disasters, or terrorism.

Upmarket. Upmarket stories are often written for and/or focus on upper class people who live in an upscale environment.

Western Genre. Western stories are those that take place in the west during the late 19th century and early 20th century. Characters include cowboys, outlaws, native Americans, and settlers.

2. Nonfiction Genres

From the BISAC categories, a globally accepted system for coding and categorizing books by the Book Industry Standards And Communications group.

Antiques & Collectibles. Nonfiction books about antiques and collectibles include those that focus on topics such as collecting, appraising, restoring, and marketing antiques and collectibles. These books may be written for both collectors and dealers in antique and collectible items. They can range from how-to guides to detailed histories of specific types of objects.

Architecture. Architecture books focus on the design, construction, use, and history of buildings and structures. This includes the study of architecture in general, but also the specific designs of individual buildings or styles of architecture.

Art. Art books focus on visual arts, music, literature, dance, film, theater, architecture, design, fashion, food, and other art forms. They may include essays, memoirs, biographies, interviews, criticism, and reviews.

Bibles. Bibles are religious books, almost exclusively Christian, that contain the traditional Bible in various translations, often with commentary or historical context.

Biography & Autobiography. Biography is an account of a person's life, often a historical or otherwise famous person. Autobiographies are personal accounts of people's lives written by themselves.

Body, Mind & Spirt. These books focus on topics related to human health, wellness, nutrition, fitness, or spirituality.

Business & Economics. Business & economics books are about how businesses work. They tend to focus on topics that interest people who run their own companies, lead or manage others, or want to understand how the economy works.

Computers. The computer genre of nonfiction books includes any topics that deal with computers in some way. They can be about general use, about how they affect our lives, or about specific technical areas related to hardware or software.

Cooking. Cookbooks contain recipes or cooking techniques.

Crafts & Hobbies. How-to guides for crafts and hobbies, including sewing, knitting, painting, baking, woodworking, jewelry making, scrapbooking, photography, gardening, home improvement projects, and others.

Design. Design books are written about topics that include design in some way. They can be about any aspect of design including graphic design, industrial design, product design, fashion, furniture, interior design, or others.

Education. Education books focus on topics related to teaching and learning in schools. They can be used for students or as a resource for teachers.

Family & Relationships. These books focus on family relationships, including parenting, marriage, divorce, adoption, and more.

Foreign Language Study. Books that act as a reference or guide to learning a foreign language.

Games & Activities. Games & activities books may be published for children or adults, may contain learning activities or entertaining word or puzzle games. They range from joke books to crossword puzzle books to coloring books and more.

Gardening. Gardening books include those that focus on aspects of gardening, how to prepare for and grow vegetables, fruits, herbs, flowers, trees, shrubs, grasses, and other plants in an indoor or outdoor garden setting.

Health & Fitness. Health and fitness books focus on topics like dieting, exercise, nutrition, weight loss, health issues, medical conditions, diseases, medications, herbs, supplements, vitamins, minerals, and more.

History. History books focus on historical events and people, and may be written for entertainment or educational purposes.

House & Home. House & home books focus on topics like interior design, decorating, entertaining, and DIY projects.

Humor. Humor books are contain humorous elements but do not have any fictional elements.

Juvenile Nonfiction. These are nonfiction books written for children between six and twelve years old.

Language Arts & Disciplines. These books focus on teaching language arts and disciplines. They may be used for elementary school students in grades K-5.

Law. Law books include legal treatises, casebooks, and collections of statutes.

Literary Criticism. Literary criticism books discuss literary works, primarily key works of fiction or memoir. They may include biographies of authors, critical essays on specific works, or studies of the history of literature.

Mathematics. Mathematics books either teach mathematical concepts and methods or explore the history of mathematics.

Medical. Medical books include textbooks, reference books, guides, encyclopedias, and handbooks that focus on fields of medicine, including general practice, internal medicine, surgery, pediatrics, obstetrics/gynecology, and more.

Music. Music books are books that focus on the history, culture, and development of music in various countries around the world. They often include biographies, interviews, reviews, essays, and other related material. However, they may also include sheet music or instruction on playing a specific instrument.

Nature. Nature books focus on the natural world or environment, including natural history, ecology, or natural experiences like hiking, bird watching, or conservation.

Performing Arts. Books about the performing arts in general, including specific types of performance art like dance, music, and theater.

Pets. Pet books include any book that deals with animals in some way, including dog training, cat care, animal behavior, pet nutrition, bird care, and more.

Philosophy. Philosophy books deal with philosophical issues, and may be written for a general audience or specifically for scholars.

Photography. Photography books use photographs as an essential part of their content. They may be about any subject.

Political Science. Political science books deal with politics in some way. They can be about current events, historical figures, or theoretical concepts.

Psychology. Psychology books are about the scientific study of mental processes, emotion, and behavior.

Reference. Reference books are about any subject, topic, or field and contain useful information about that subject, topic or field.

Religion. These books deal with religion in some way, including religious history, theology, philosophy, and spirituality.

Science. Science books focus on topics within scientific fields, including geology, biology, physics, and more.

Self-Help. Self-help books are written for people who want to improve their lives in some way. They may be about health, relationships, finances, career, parenting, spirituality, or any number of topics that can help readers achieve personal goals.

Social Science. Focus on social science topics.

Sports & Recreation. Sports & Recreation books focus on sports either from a reporting, historical, or instructional perspective.

Study Aids. Study aids are books that provide information about a particular subject area for students who want to learn more about that topic. These books can be used in conjunction with classroom instruction or on their own.

Technology & Engineering. Technology & engineering nonfiction books describe how technology has changed our lives and how we can use that knowledge to improve ourselves and society.

Transportation. Focus on transportation topics including those about vehicles, routes, or techniques.

Travel. Travel books are those that focus on travel experiences, whether from a guide perspective or from the author's personal experiences.

True Crime. True Crime books focus on true stories about crimes. These books may be about famous cases, unsolved crimes, or specific criminals.

Young Adult Nonfiction. Young adult nonfiction books are written for children and teenagers.

3. Drama Genres

These include genres for theater, film, television serials, or audio plays.

As a writer, I find some of these genres particularly eye-roll worthy. And yet, this is the way most films, television shows, and even theater productions are classified.

Action. Action genre dramas involve fast-paced, high-energy sequences in which characters fight against each other. They often have large-scale battles, chase scenes, or other high-intensity, high-conflict scenes.

Horror. Horror dramas focus on the psychological terror experienced by their characters. They often feature supernatural elements, such as ghosts, vampires, werewolves, zombies, demons, monsters, and aliens.

Adventure. Adventure films are movies that have an adventurous theme. They may be set in exotic locations, feature action sequences, and/or contain elements of fantasy.

Musicals (Dance). Musicals are dramas that use music in their plot and/or soundtrack. They may be comedies, dramas, or any combination.

Comedy (& Black Comedy). Comedy dramas feature humor in their plots, characters, dialogue, or situations. It sometimes refers to historical dramas (e.g. Shakespeare, Greek drama, etc) that contain a happy ending, often with a wedding.

Science Fiction. Science fiction dramas are usually set in an imaginary future world, often involving advanced technology. They may be based on scientific facts but do not have to be.

Crime & Gangster. Crime & Gangster dramas deal with criminals, detectives, or organized crime groups. They often feature action sequences, violence, and mystery elements.

War (Anti-War). War (or anti-war) dramas focus on contemporary or historical wars. They may also contain action, adventure, mystery, or romance elements.

Drama. Dramas focus on human emotions in conflict situations. They often have complex plots and characters, and deal with serious themes. This may also refer to historical stories (e.g. Shakespeare, Greek Literature, etc) that contain a sad or tragic ending, often with one or more deaths.

Westerns. Westerns are a genre of American film that originated in the early 20th century and take place in the west during the late 19th century and early 20th century. Characters include cowboys, outlaws, native Americans, and settlers.

Epics/Historical/Period. These are dramas based on historical events or periods but do not necessarily involve any real people.

Biographical (“Biopics”). Biopics films are movies that focus on real people in history.

Melodramas, Women's or “Weeper” Films, Tearjerkers. A type of narrative drama that focuses on emotional issues, usually involving love, loss, tragedy, and redemption.

“Chick” Flicks. Chick flicks usually feature romantic relationships and tend to be lighthearted and comedic in nature.

Road Stories. Dramas involving a journey of some kind, usually taking place in contemporary setting, and involving relationships between one or more people, not necessarily romantic.

Courtroom Dramas. Courtroom dramas depict legal cases set in courtrooms. They usually have a dramatic plot line with an interesting twist at the end.

Romance. Romance dramas feature love stories between two people. Romance dramas tend to be more serious, even tragic, in nature, while romantic comedies tend to be more lighthearted.

Detective & Mystery. These dramas feature amateur or professional investigators solving crimes and catching criminals.

Sports. Sports dramas focus on athletic competition in its many forms and usually involve some kind of climactic tournament or championship.

Disaster. Disaster dramas are adventure or action dramas that include natural disasters, usually involving earthquakes, floods, volcanoes, hurricanes, tornadoes, or other disasters.

Superhero. Superhero dramas are action/adventure dramas that feature characters with supernatural powers. They usually have an origin story, the rise of a villain, and a climactic battle at the end.

Fantasy. Fantasy dramas films are typically adventure dramas that feature fantastical elements in their plot or setting, whether magic, folklore, supernatural creatures, or other fantasy elements.

Supernatural. Supernatural dramas feature paranormal phenomena in their plots, including ghosts, mythical creatures, and mysterious or extraordinary elements. This genre may overlap with horror, fantasy, thriller, action and other genres.

Film Noir. Film noir refers to a style of American crime drama that emerged in the 1940s. These dramas often featured cynical characters who struggled, often fruitlessly, against corruption and injustice.

Thriller/Suspense. Thriller/suspense dramas have elements of suspense and mystery in their plot. They usually feature a character protagonist who must overcome obstacles while trying to solve a crime or prevent a catastrophe.

Guy Stories. Guy dramas feature men in various situations, usually humorous or comedic in nature.

Zombie . Zombie dramas are usually action/adventure dramas that involve zombies.

Animated Stories . Dramas that are depicted with drawings, photographs, stop-motion, CGI, or other animation techniques.

Documentary . Documentaries are non-fiction performances that attempt to describe actual events, topics, or people.

“Foreign.” Any drama not in the language of or involving characters/topics in your country of origin. They can also have any of the other genres listed here.

Childrens – Kids – Family-Oriented . Dramas with children of various ages as the intended audience.

Sexual – Erotic . These dramas feature explicit sexual acts but also have some kind of plot or narrative (i.e. not pornography).

Classic . Classic dramas refer to dramas performed before 1950.

Silent . Silent dramas were an early form of film that used no recorded sound.

Cult . Cult dramas are usually small-scale, independent productions with an offbeat plot, unusual characters, and/or unconventional style that have nevertheless gained popularity among a specific audience.

4. Poetry Genres

This list is from Harvard's Glossary of Poetic Genres who also has definitions for each genre.

Dramatic monologue

Epithalamion

Light verse

Occasional verse

Verse epistle

What Are the Components of Genre In Literature? The 7 Elements of Genre

Now that we've looked, somewhat exhaustively, at examples of literary genres, let's consider how these genres are created.

What are the elements of literary genre? How are they formed?

Here are seven components that make up genre.

- Form . Length is the main component of form (e.g. a novel is 200+ pages , films are at least an hour, serialized episodes are about 20 minutes, etc), but may also be determined by how many acts or plot lines they have. You might be asking, what about short stories? Short stories are a genre defined by their length but not their content.

- Intended Audience . Is the story meant for adults, children, teenagers, etc?

- Conventions and Tropes . Conventions and tropes describe patterns or predictable events that have developed within genres. For example, a sports story may have a big tournament at the climax, or a fantasy story may have a mentor character who instructs the protagonist on the use of their abilities.

- Characters and Archetypes. Genre will often have characters who serve similar functions, like the best friend sidekick, the evil villain , the anti-hero , and other character archetypes .

- Common Settings and Time Periods . Genre may be defined by the setting or time period. For example, stories set in the future tend to be labelled science fiction, stories involving the past tend to be labelled historical or period, etc.

- Common Story Arcs . While every story type may use each of the six main story arcs , genre tends to be defined by specific story arcs. For example, comedy almost always has a story arc that ends positively, same with kids or family genres. However, dramas often (and when referring to historical drama, always) have stories that end tragically.

- Common Elements (such as supernatural elements, technology, mythical creatures, monsters, etc) . Some genres center themselves on specific elements, like supernatural creatures, magic, monsters, gore, and so on. Genre can be determined by these common elements.

As you consider these elements, keep in mind that genre all comes back to taste, to what readers want to consume and how to match the unlimited variations of story with the infinite variety of tastes.

Read What You Want, Write What You Want

In the end, both readers and writers should use genre for what it is, a tool, not as something that defines you.

Writers can embrace genre, can use genre, without being controlled by it.

Readers can use genre to find stories or books they enjoy while also exploring works outside of that genre.

Genre can be incredibly fun! But only if you hold it in tension with your own work of telling (or finding) a great story.

What are your favorite genres to read in? to write in? Let us know in the comments!

Now that we understand everything there is to know about literary genres, let's put our knowledge to use with an exercise. I have two variations for you today, one for readers and one for writers.

Readers : Think of one of your favorite stories. What is the literary genre of that story? Does it have multiple? What expectations do you have about stories within that genre? Finally, how does the author of your favorite story use those expectations, and how do they subvert them?

Writers : Choose a literary genre from the list above and spend fifteen minutes writing a story using the elements of genre: form, audience, conventions and tropes, characters and archetypes, setting and time periods, story arcs, and common elements.

When you’re finished, share your work in the Pro Practice Workshop here . Not a member yet? Join us here !

Joe Bunting

Joe Bunting is an author and the leader of The Write Practice community. He is also the author of the new book Crowdsourcing Paris , a real life adventure story set in France. It was a #1 New Release on Amazon. Follow him on Instagram (@jhbunting).

Want best-seller coaching? Book Joe here.

So how big does an other-genre element need to get before you call your book “cross-genre”? Right now, I’m writing a superhero team saga (which is already a challenge for platforms that don’t recognize “superhero” as a genre, since my team’s powers lie in that fuzzy land where the distinction between science and magic gets more than a little blurry), so it obviously has action/adventure in it, but it’s also sprouting thriller and mystery elements. I’m wondering if they’re big enough to plug the series to those genres.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Submit Comment

Join over 450,000 readers who are saying YES to practice. You’ll also get a free copy of our eBook 14 Prompts :

Popular Resources

Book Writing Tips & Guides Creativity & Inspiration Tips Writing Prompts Grammar & Vocab Resources Best Book Writing Software ProWritingAid Review Writing Teacher Resources Publisher Rocket Review Scrivener Review Gifts for Writers

Books By Our Writers

You've got it! Just us where to send your guide.

Enter your email to get our free 10-step guide to becoming a writer.

You've got it! Just us where to send your book.

Enter your first name and email to get our free book, 14 Prompts.

Want to Get Published?

Enter your email to get our free interactive checklist to writing and publishing a book.

What's the Difference Between Classical and Classic Literature?

David Masters/Flickr/CC BY 2.0

- Authors & Texts

- Top Picks Lists

- Study Guides

- Best Sellers

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

- M.A., English Literature, California State University - Sacramento

- B.A., English, California State University - Sacramento

Some scholars and writers use the terms "classical" and "classic" interchangeably when it comes to literature. However, each term actually has a separate meaning. The list of books that are considered classical versus classic books differs greatly. What confuses things further is that classical books are also classic. A work of classical literature refers only to ancient Greek and Roman works, while classics are great works of literature throughout the ages.

What Is Classical Literature?

Classical literature refers to the great masterpieces of Greek, Roman, and other ancient civilizations. The works of Homer , Ovid , and Sophocles are all examples of classical literature. The term isn't just limited to novels. It can also include epic, lyric, tragedy, comedy, pastoral, and other forms of writing. The study of these texts was once considered to be a necessity for students of the humanities. Ancient Greek and Roman authors were viewed to be of the highest quality. The study of their work was once seen as the mark of elite education. While these books generally still find their way into high school and college English classes, they are no longer commonly studied. The expansion of literature has offered readers and academics more to choose from.

What Is Classic Literature?

Classic literature is a term most readers are probably familiar with. The term covers a much wider array of works than classical literature. Older books that retain their popularity are almost always considered to be among the classics. This means that the ancient Greek and Roman authors of classical literature fall into this category as well. It's not just age that makes a book a classic, however. Books that have a timeless quality are considered to be in this category. While determining if a book is well-written or not is a subjective endeavor, it is generally agreed that classics have high-quality prose.

What Makes a Book a Classic?

While most people are referring to literary fiction when they refer to the classics , each genre and category of literature has its own classics. For example, the average reader might not consider Steven King's novel "The Shining," the story of a haunted hotel, to be a classic, but those who study the horror genre may. Even within genres or literary movements, books that are considered classic are those that are well-written and/or have cultural importance. A book that may not have the best writing but was the first book in a genre to do something ground-breaking is a classic. For example, the first romance novel that took place in a historic setting is culturally significant to the romance genre.

- The Greatest Works of Russian Literature

- A List of Every Nobel Prize Winner in English Literature

- What Is a Novel? Definition and Characteristics

- A Brief History of English Literature

- Romanticism in Literature: Definition and Examples

- Comparing and Contrasting Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome

- Classical Writers Directory

- What Is a Modern Classic in Literature?

- Literature Definitions: What Makes a Book a Classic?

- Classic Works of Literature for a 9th Grade Reading List

- Genres in Literature

- Recommended Reads for High School Freshmen

- An Introduction to Metafiction

- Gothic Literature

- Anthology: Definition and Examples in Literature

- Renaissance Architecture and Its Influence

Characterization

Characterization Definition

What is characterization? Here’s a quick and simple definition:

Characterization is the representation of the traits, motives, and psychology of a character in a narrative. Characterization may occur through direct description, in which the character's qualities are described by a narrator, another character, or by the character him or herself. It may also occur indirectly, in which the character's qualities are revealed by his or her actions, thoughts, or dialogue.

Some additional key details about characterization:

- Early studies of literature, such as those by the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle, saw plot as more important than character. It wasn't until the 15th century that characters, and therefore characterization, became more crucial parts of narratives.

- Characterization became particularly important in the 19th century, with the rise of realist novels that sought to accurately portray people.

Characterization Pronunciation

Here's how to pronounce characterization: kar-ack-ter-ih- zey -shun

Direct and Indirect Characterization

Authors can develop characterization in two ways: directly and indirectly. It's important to note that these two methods are not mutually exclusive. Most authors can and do use both direct and indirect methods of characterization to develop their characters.

Direct Characterization

In direct characterization, the author directly describes a character's qualities. Such direct description may come from a narrator, from another character, or through self-description by the character in question. For instance, imagine the following dialogue between two characters:

"That guy Sam seems nice." "Oh, no. Sam's the worst. He acts nice when you first meet him, but then he'll ask you for money and never return it, and eat all your food without any offering anything in return, and I once saw him throw a rock at a puppy. Thank God he missed."

Here the second speaker is directly characterizing Sam as being selfish and cruel. Direct characterization is also sometimes called "explicit characterization."

Indirect Characterization

In indirect characterization, rather than explicitly describe a character's qualities, an author shows the character as he or she moves through the world, allowing the reader to infer the character's qualities from his or her behavior. Details that might contribute to the indirect characterization of a character are:

- The character's thoughts.

- The character's actions.

- What a character says (their choice of words)

- How a character talks (their tone, dialect, and manner of speaking)

- The character's appearance

- The character's movements and mannerisms

- How the character interacts with others (and how others react to the character)

Indirect characterization is sometimes called "implicit characterization."

Indirect Characterization in Drama

It's worth noting that indirect characterization has an additional layer in any art form that involves actors, including film, theater, and television. Actors don't just say the words on the script. They make choices about how to say those words, how to move their own bodies and in relation to other character. In other words, actors make choices about how to communicate all sorts of indirect details. As a result, different actors can portray the same characters in vastly different ways.

For instance, compare the way that the the actor Alan Bates plays King Claudius in this play-within-a-play scene from the 1990 movie of Hamlet, versus how Patrick Stewart plays the role in the same scene from a 2010 version. While Bates plays the scene with growing alarm and an outburst of terror that reveals his guilt, Stewart plays his Claudius as ice cold and offended, but by no means tricked by Hamlet's little play-within-a-play into revealing anything.

Round and Flat Characters

Characters are often described as being either round or flat.

- Round characters : Are complex, realistic, unique characters.

- Flat characters : Are one-dimensional characters, with a single overarching trait and otherwise limited personality or individuality.

Whether a character is round or flat depends on their characterization. In some cases, an author may purposely create flat characters, particularly if those characters will appear only briefly and only for a specific purpose. A bully who appears in a single scene of a television show, for instance, might never get or need more characterization than the fact that they act like a bully.

But other times authors may create flat characters unintentionally when round characters were necessary, and such characters can render a narrative dull, tensionless, and unrealistic.

Character Archetypes

Some types of characters appear so often in narratives that they come to seen as archetypes —an original, universal model of which each particular instance is a kind of copy. The idea of the archetype was first proposed by the psychologist Carl Jung, who proposed that there were twelve fundamental "patterns" that define the human psyche. He defined these twelve archetypes as the:

While many have disagreed with the idea that any such twelve patterns actually psychologically define people, the idea of archetypes does hold a lot of sway among both those who develop and analyze fictional characters. In fact, another way to define round and flat character is to think about them as they relate to archetypes:

- Flat characters are easy to define by a single archetype, and they do not have unique personal backgrounds, traits, or psychology that differentiates them from that archetype in a meaningful way.

- Round characters may have primary aspects that fit with a certain archetype, but they also may be the combination of several archetypes and also have unique personal backgrounds, behaviors, and psychologies that make them seem like individuals even as they may be identifiable as belonging to certain archetypes.

Good characterization often doesn't involve an effort to avoid archetype altogether—archetypes are archetypes, after all, because over human history they've proved to be excellent subjects for stories. But successful authors will find ways to make their characters not just archetypes. They might do so by playing with or subverting archetypes in order to create characters who are unexpected or new, or more generally create characters whose characterization makes them feel so unique and individual that their archetype feels more like a framework or background rather than the entirety of who that character is.

Characterization Examples

The characters of nearly every story—whether in literature, film, or any other narrative—have some characterization. Here are some examples of different types of characterization.

Characterization in Hamlet

The famous literary critic Harold Bloom has argued in his book The Invention of the Human that "Personality, in our sense, is a Shakespearean invention." Whether or not you agree with that, there's no doubting that Shakespeare was a master of characterization. One way he achieved such characterization was through his characters delivering soliloquies . The excerpt of a soliloquy below is from Hamlet , in which Hamlet considers suicide:

To be, or not to be? That is the question— Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, Or to take arms against a sea of troubles, And, by opposing, end them? To die, to sleep— No more—and by a sleep to say we end The heartache and the thousand natural shocks That flesh is heir to—’tis a consummation Devoutly to be wished! To die, to sleep. To sleep, perchance to dream—ay, there’s the rub, For in that sleep of death what dreams may come When we have shuffled off this mortal coil, Must give us pause.

Hamlet's soliloquy is not simply him saying what he thinks. As he delivers the soliloquy, he discovers what he thinks. When he says "To die, to sleep. To sleep," he is all-in on the idea that suicide is the right course. His words "perchance to dream" flow directly out of his thoughts about death as being like "sleep." And with his positive thoughts of death as sleep, when he first says "perchance to dream" he's thinking about having good dreams. But as he says the words he realizes they are deeper than he originally thought, because in that moment he realizes that he doesn't actually know what sort of dreams he might experience in death—they might be terrible, never-ending nightmares. And suddenly the flow of his logic leaves him stuck.

In showing a character experiencing his own thoughts the way that real people experience their thoughts, not as a smooth flow but as ideas that spark new and different and unexpected ideas, Shakespeare gives Hamlet a powerful humanity as a character. By giving Hamlet a soliloquy on the possible joy of suicide he further captures Hamlet's current misery and melancholy. And in showing how much attention Hamlet pays to the detail of his logic, he captures Hamlet's rather obsessive nature. In other words, in just these 13 lines Shakespeare achieves a great deal of characterization.

Characterization in The Duchess of Malfi

In his play the The Duchess of Malfi , John Webster includes an excellent example of direct characterization. In this speech, the character Antonio tells his friend about Duke Ferdinand:

The Duke there? A most perverse and turbulent nature; What appears in him mirth is merely outside. If he laugh heartily, it is to laugh All honesty out of fashion. … He speaks with others' tongues, and hears men's suits With others' ears; will seem to sleep o’th' bench Only to entrap offenders in their answers; Dooms men to death by information, Rewards by hearsay.

Ferdinand directly describes the Duke as deceitful, perverse, and wild, and as a kind of hollow person who only ever laughs for show. It is a devastating description, and one that turns out to be largely accurate.

Characterization in The Great Gatsby

Here's another example of direct characterization, this time from The Great Gatsby . Here, Nick Carraway, the narrator of the novel, describes Tom and Daisy Buchanan near the end of the novel.

They were careless people, Tom and Daisy—they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness, or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made.

But The Great Gatsby, like essentially all other literature, doesn't solely rely on direct characterization. Here is Nick, earlier in the novel, describing Gatsby:

He stretched out his arms toward the dark water in a curious way, and, far as I was from him, I could have sworn he was trembling. Involuntarily I glanced seaward—and distinguished nothing except a single green light, minute and far away, that might have been the end of a dock.

This is an example of indirect characterization. Nick isn't describing Gatsby character directly, instead he's describing how Gatsby is behaving, what Gatsby is doing. But that physical description—Gatsby reaching out with trembling arms toward a distant and mysterious green light—communicates fundamental aspects of Gatsby's character: his overwhelming yearning and desire, and perhaps also the fragility inherent such yearning.

Why Do Writers Use Characterization?

Characterization is a crucial aspect of any narrative literature, for the simple reason that complex, interesting characters are vital to narrative literature. Writers therefore use the techniques of characterization to develop and describe characters':

- Motivations

- History and background

- Interests and desires

- Skills and talents

- Self-conception, quirks, and neuroses

Such characteristics in turn make characters seem realistic and also help to drive the action of the plot, as a plot is often defined by the clash of actions and desires of its various characters.

Other Helpful Characterization Resources

- Wikipedia entry on characterization: A brief but thorough entry.

- Archetypal characters: The website TV tropes has built a vast compendium of different archetypal characters that appear in film and television (and by extension to books).

- Encyclopedia Britannica on characters: A short entry on flat and round characters.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1956 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 41,253 quotes across 1956 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

- Flat Character

- Round Character

- Antimetabole

- Rhyme Scheme

- Static Character

- Dynamic Character

- Point of View

- Verbal Irony

- Internal Rhyme

- Foreshadowing

- Protagonist

- Climax (Figure of Speech)

TRY OUR FREE APP

Write your book in Reedsy Studio. Try the beloved writing app for free today.

Craft your masterpiece in Reedsy Studio

Plan, write, edit, and format your book in our free app made for authors.

Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Feb 07, 2023

What is Literary Fiction? The Ultimate Guide in 2024

Literary fiction is a category of novels that emphasize style, character, and theme over plot. Lit fic is often defined in contrast to genre fiction and commercial fiction , which involve certain tropes and expectations for the storyline; literary fiction has no such plot-based hallmarks.

Though it's a tough category to define, you can certainly spot literary fiction once you know what you're looking for. Intrigued? In this short guide, we’ll unpack this elusive category and give you tips for writing with literary readers in mind.

Literary fiction is not a standalone genre

You will rarely see novels marketed as ‘literary fiction’, or even shelved that way in a bookstore. This is because literary fiction still shares some features with genre and commercial fiction, though they’re presented more subtly in lit fic. But even when it’s shelved alongside commercial fiction, literary fiction has a few telltale signs, as you’ll soon see.

It’s considered a prestige category

Literary fiction novels are often seen as prestige items in a publisher’s list: cutting-edge works of ‘serious fiction’ by artists of the written word. As a result, literary fiction — even from debut authors — will often get an initial hardback release. If you see a new hardcover on prominent display at the bookstore, it’s almost guaranteed to be literary fiction.

This strategy not only gives it a chance to be seen by plenty of devoted readers, it also increases the book’s chances of being reviewed. According to the editor of The Bookseller in 2018, some literary editors will only review novels launched in hardback .

Books in this category are also privy to publishing’s biggest prizes, such as the Booker Prize and the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. So if you see a sticker on the cover boasting that it’s been nominated for a prestigious award, you’re likely looking at a work of literary fiction.

Style and theme take priority

Another key quality of literary fiction is its attention to style, which in turn underscores major themes. Of course, when thinking of literary fiction, people tend to imagine ‘highbrow’ or difficult prose. This has led to generations of aspiring literary authors packing their prose with run-on sentences, florid metaphors, and other rhetorical bells and whistles.

While this stereotype is certainly true of some novelists (James Joyce, for example, was no stranger to run-on sentences), many literary authors favor concise prose over fancy linguistic flourishes. Take it from George Orwell, who lived by the maxim “never use a complicated word when a simple one will do” — or Hemingway, whose famously lean prose has taught generations of writers that less is more.

Basically, though you may associate literary fiction with insufferable purple prose , it doesn’t have to be that way. The defining feature of literary fiction isn’t one specific style of prose, but rather its impact on the reader, and its ability to deliver or embody the book’s theme.

If you struggle to write consistently, sign up for our How to Write a Novel course to finish a novel in just 3 months.

NEW REEDSY COURSE

How to Write a Novel

Enroll in our course and become an author in three months.

Themes are explored in depth

Indeed, literary fiction isn’t all style over substance: meaningful themes are just as important in this category. After all, what use is an interesting voice if you don’t have anything to say?

Literary fiction commonly examines ‘serious’ concepts like politics, social issues, and psychological conflict. But what makes the themes in literary fiction stand apart from those in genre fiction is the level of detail and narrative weight they’re given.

For example, Orwell’s Animal Farm is defined by its commentary on political structures. The plot and characters are just small parts that build the novel’s overarching metaphor for the Russian Revolution, as seen through Orwell’s satirical lens.

As you can probably guess, the level of nuance required to explore serious themes calls for a great deal of time and effort on the author’s part. After all, it’s not easy to have a strong take on a weighty topic, and (crucially) understand how impacted characters would think, feel, and react — so if you intend to write literary fiction with big themes, make sure you’ve thought deeply about the real-world consequences.

They often drill into a single theme

Now, one might argue that The Hunger Games also tackles serious themes of social inequality — so how come it’s not considered literary fiction? Well, because this dystopian novel more strongly foregrounds elements of romance, coming of age, and an action-packed plot. The social themes, in many ways, are garnishes rather than the main course.

In short, genre fiction’s focus on story means that it will rarely explore themes in as much depth as literary fiction. This thematic intensity doesn't make literary fiction “better” than genre fiction, or vice-versa — it just goes to show that there are many different approaches out there to meet the varied needs of different readers.

Character studies are its bread and butter

While authors of genre fiction certainly can’t ignore character-based storytelling , their equal (or greater) focus on plot gives them less opportunity to drill deep into a character’s inner life. What’s more, most genre fiction has a protagonist who is lovable by design.

Meanwhile, in literary fiction, you’re much more likely to encounter morally gray and flawed characters , and find yourself absorbed by their history and psyche. That’s not to say every character in this category is inherently evil, incredibly flawed, or unlikable — they're just far more likely to be approached in a more complex way that exposes their faults, thus giving you the tools to dissect them.

Take The Catcher in the Rye as an example. J.D. Salinger’s hero is Holden Caulfield, a seventeen-year-old boarding school drop-out. Holden isn’t necessarily likable — in fact, he often alienates others by judging superficial characteristics extremely critically — but readers are intrigued by the book’s psychological insights into his personality. Though Holden is quick to judge others, particularly those he views as “phony”, he’s far from perfect himself; this makes trying to understand his behavior even more compelling.

Instead of making Holden likable, Salinger makes the reader empathize with him despite his personality and actions — something that’s arguably much harder to do as an author. This challenging, thought-provoking nature is a definite hallmark of literary fiction.

FREE COURSE

How to Develop Characters

In 10 days, learn to develop complex characters readers will love.

The tone is often realistic and introspective

What do Of Mice and Men, Mrs Dalloway, The Remains of the Day have in common besides their dark elements and focus on longing? While none of these books would be mistaken for nonfiction , they are all grounded in a certain realism — their writers have taken special care in exploring the emotions and reactions of their characters in very specific settings.

Considering this, it won’t surprise you that literary fiction tends to rely on internal conflict of a character to drive the plot. In Of Mice and Men, for example, migrant farm worker George Milton is torn between his survival instincts and his loyalty to his simple (yet dangerous) friend, Lenny. While the novel arguably does have a villain — the landowner’s cruel son — the story’s true conflict takes place in George’s mind.

You might also look to Mrs Dalloway as a good example of realistic introspection. In this book, readers follow a single day in the life of Clarissa Dalloway, culminating in her finally reconciling herself with life in the present — despite her strong attachments to the past.

The Remains of the Day creates a similar air of realism by exploring the human psyche: we follow the butler of a grand English estate as he comes to terms with how his unhealthy devotion to his work, subsequent repression, and his fears of intimacy have held him back for years.

It’s about the journey

But while the resolutions of all these stories may be melancholy and uncertain, sad endings alone don’t make them lit fic — it’s about the characters’ journeys to get there.

Good literary fiction feels so real because there isn’t that certainty of a happily ever after. After this, the characters will continue on their journey, and readers can only imagine where they might go. They want to wonder what will happen to the characters based on what they’ve learned through the story, rather than simply arrive at an ending that’s wrapped up in a bow.

That literary fiction writers allude to this “to be continued” reality in their novels, makes them that much more believable.

But it can also be fanciful!

Literary fiction isn’t all dark character studies about people living on the verge of despair, mumbling to each other in a studio apartment. On the contrary, literary fiction can absolutely be fantastical while simultaneously presenting people and themes in a believable way — and what better way to study human nature than by throwing your characters into highly unusual situations?

Plenty of literary fiction writers actually specialize in playing with genre tropes and devising the most inventive concepts. One recent example of fantasy-infused literary fiction is Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi , which follows Piranesi — a man who seemingly lives alone in a vast, statue-filled labyrinth that periodically floods to dangerous levels. Let’s be honest, not much besides the human insight is realistic in this novel (unless you happen to holiday in similar dangerous labyrinths). But the outlandish premise makes the perfect playground for Clarke to explore themes of personhood and isolation.

You might also point to Susan Hill’s The Woman in Black , a novel which is equal parts literary fiction and Gothic horror. Arthur Kipps is a young lawyer investigating a creepy house on a remote island — one that belonged to his deceased client.

Through Kipps’s seemingly supernatural experiences at the house, readers are asked to consider bigger questions about sanity and objectivity. While the harrowing events in this novel are hardly realistic in the way that a Sally Rooney novel might be, its rich narration, focus on human psychology, and themes of isolation align it with literary fiction.

Authors are more free to experiment

Writers of literary fiction benefit from the fact that their readers tend to enjoy more challenging works. In genre and commercial fiction, there is an expectation that the writer will always engage the reader, propelling them through the book with quickly mounting tension. In contrast, literary fiction readers are more flexible in their initial expectations — understanding that a slow start can still build to a satisfying reveal later.

A great example of slow-burn literary fiction is Margaret Atwood’s The Blind Assassin , in which elderly Iris Chase recounts her dramatic life and the events leading up to her sister's death. Though this novel has received wide critical acclaim, a lot of readers have unfortunately placed this challenging book back on the shelf early because of its slow-paced beginning. However, the novel’s unique ‘memory recall’ structure needs that time to build the twisting mysteries which ultimately make it a true page turner.

Indeed, literary fiction readers often expect some level of experimentation that subverts the formal conventions of storytelling. Sarah Waters’s The Night Watch overturns readers' expectations by telling its story in reverse, moving backwards through the 1940s, starting in 1947. Waters’s unconventional style challenges readers by asking them to forget their curiosity about the future and try to focus solely on unraveling the past.

Of course, experimental or unusual structures aren’t just used in literary fiction for the sake of challenging readers. Typically, a nuanced structure works towards immersing the reader in the character or world of the book.

For example, a long stream of consciousness narrative (think Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea , in which the narrator’s thoughts gradually become harder to follow) might be a great way to make readers lose themselves in the narrator’s mental decline. Or utilizing an epistolary structure (as in Lionel Shriver’s We Need to Talk About Kevin , which is told through a series of letters penned by a grieving mother) can really make the stakes feel tangible as readers dig through years of correspondence.

Literary fiction is a broad and diverse genre, so it’s pretty difficult to track down an exact definition ― but hopefully, equipped with this field guide to lit fic, you’ll feel more confident identifying it when you come across it in the wild.

If all this literary talk has you feeling inspired, make sure to head over to the next part of our guide, where you can learn 10 insightful tips for writing your own literary fiction!

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

We made a writing app for you

Yes, you! Write. Format. Export for ebook and print. 100% free, always.

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

In order to continue enjoying our site, we ask that you confirm your identity as a human. Thank you very much for your cooperation.

How to Read and Enjoy the Classics

- Thoughts on the Greats

- How to Read Poetry

- How to Read Fiction

- Why Literature?

- Lists and Timelines

- Literature Q & A

Four Qualities that Make Great Literature Special

Classic literature is like this beautiful Live Oak tree in Natchitoches, Louisiana: it lasts for hundreds of years, growing in beauty and complexity every time someone regards it.*

If you are an avid reader, I clasp you to my heart, whatever and why ever you are reading—for pleasure, escape, knowledge, social concerns. There are a myriad of good, and even mediocre, books and poetry that can keep us entertained, or give us vicarious experiences of unknown places and times, or inform our opinions on social issues.

But what I am here to advocate, and why I have started this site, is that Classic Literature—truly Great Literature—is something different, something especially worth treasuring, preserving, learning about, experiencing, re-reading, and pondering. The experience, the grace given to the mind and soul, is a larger, higher experience than that offered by the average popular novel or poem or drama, well-crafted though each may be.