Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved June 7, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, what is your plagiarism score.

Health (Nursing, Medicine, Allied Health)

- Find Articles/Databases

- Reference Resources

- Evidence Summaries & Clinical Guidelines

- Drug Information

- Health Data & Statistics

- Patient/Consumer Facing Materials

- Images and Streaming Video

- Grey Literature

- Mobile Apps & "Point of Care" Tools

- Tests & Measures This link opens in a new window

- Citing Sources

- Selecting Databases

- Framing Research Questions

- Crafting a Search

- Narrowing / Filtering a Search

- Expanding a Search

- Cited Reference Searching

- Saving Searches

- Term Glossary

- Critical Appraisal Resources

- What are Literature Reviews?

- Conducting & Reporting Systematic Reviews

- Finding Systematic Reviews

- Tutorials & Tools for Literature Reviews

- Finding Full Text

What are Systematic Reviews? (3 minutes, 24 second YouTube Video)

Systematic Literature Reviews: Steps & Resources

These steps for conducting a systematic literature review are listed below .

Also see subpages for more information about:

- The different types of literature reviews, including systematic reviews and other evidence synthesis methods

- Tools & Tutorials

Literature Review & Systematic Review Steps

- Develop a Focused Question

- Scope the Literature (Initial Search)

- Refine & Expand the Search

- Limit the Results

- Download Citations

- Abstract & Analyze

- Create Flow Diagram

- Synthesize & Report Results

1. Develop a Focused Question

Consider the PICO Format: Population/Problem, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome

Focus on defining the Population or Problem and Intervention (don't narrow by Comparison or Outcome just yet!)

"What are the effects of the Pilates method for patients with low back pain?"

Tools & Additional Resources:

- PICO Question Help

- Stillwell, Susan B., DNP, RN, CNE; Fineout-Overholt, Ellen, PhD, RN, FNAP, FAAN; Melnyk, Bernadette Mazurek, PhD, RN, CPNP/PMHNP, FNAP, FAAN; Williamson, Kathleen M., PhD, RN Evidence-Based Practice, Step by Step: Asking the Clinical Question, AJN The American Journal of Nursing : March 2010 - Volume 110 - Issue 3 - p 58-61 doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000368959.11129.79

2. Scope the Literature

A "scoping search" investigates the breadth and/or depth of the initial question or may identify a gap in the literature.

Eligible studies may be located by searching in:

- Background sources (books, point-of-care tools)

- Article databases

- Trial registries

- Grey literature

- Cited references

- Reference lists

When searching, if possible, translate terms to controlled vocabulary of the database. Use text word searching when necessary.

Use Boolean operators to connect search terms:

- Combine separate concepts with AND (resulting in a narrower search)

- Connecting synonyms with OR (resulting in an expanded search)

Search: pilates AND ("low back pain" OR backache )

Video Tutorials - Translating PICO Questions into Search Queries

- Translate Your PICO Into a Search in PubMed (YouTube, Carrie Price, 5:11)

- Translate Your PICO Into a Search in CINAHL (YouTube, Carrie Price, 4:56)

3. Refine & Expand Your Search

Expand your search strategy with synonymous search terms harvested from:

- database thesauri

- reference lists

- relevant studies

Example:

(pilates OR exercise movement techniques) AND ("low back pain" OR backache* OR sciatica OR lumbago OR spondylosis)

As you develop a final, reproducible strategy for each database, save your strategies in a:

- a personal database account (e.g., MyNCBI for PubMed)

- Log in with your NYU credentials

- Open and "Make a Copy" to create your own tracker for your literature search strategies

4. Limit Your Results

Use database filters to limit your results based on your defined inclusion/exclusion criteria. In addition to relying on the databases' categorical filters, you may also need to manually screen results.

- Limit to Article type, e.g.,: "randomized controlled trial" OR multicenter study

- Limit by publication years, age groups, language, etc.

NOTE: Many databases allow you to filter to "Full Text Only". This filter is not recommended . It excludes articles if their full text is not available in that particular database (CINAHL, PubMed, etc), but if the article is relevant, it is important that you are able to read its title and abstract, regardless of 'full text' status. The full text is likely to be accessible through another source (a different database, or Interlibrary Loan).

- Filters in PubMed

- CINAHL Advanced Searching Tutorial

5. Download Citations

Selected citations and/or entire sets of search results can be downloaded from the database into a citation management tool. If you are conducting a systematic review that will require reporting according to PRISMA standards, a citation manager can help you keep track of the number of articles that came from each database, as well as the number of duplicate records.

In Zotero, you can create a Collection for the combined results set, and sub-collections for the results from each database you search. You can then use Zotero's 'Duplicate Items" function to find and merge duplicate records.

- Citation Managers - General Guide

6. Abstract and Analyze

- Migrate citations to data collection/extraction tool

- Screen Title/Abstracts for inclusion/exclusion

- Screen and appraise full text for relevance, methods,

- Resolve disagreements by consensus

Covidence is a web-based tool that enables you to work with a team to screen titles/abstracts and full text for inclusion in your review, as well as extract data from the included studies.

- Covidence Support

- Critical Appraisal Tools

- Data Extraction Tools

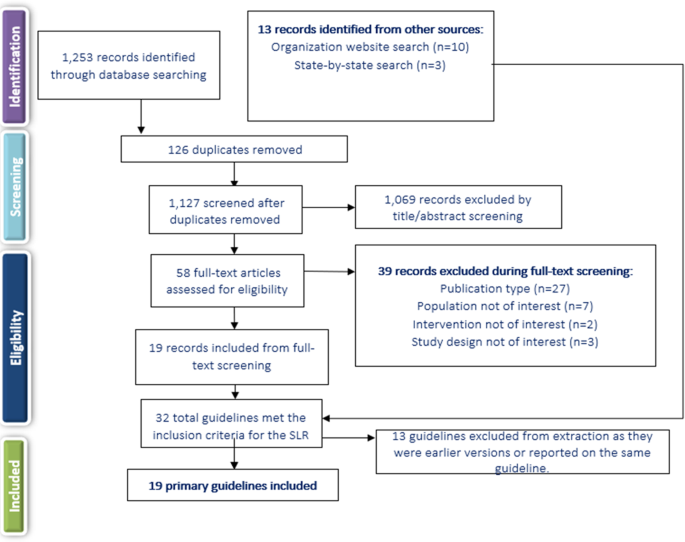

7. Create Flow Diagram

The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram is a visual representation of the flow of records through different phases of a systematic review. It depicts the number of records identified, included and excluded. It is best used in conjunction with the PRISMA checklist .

Example from: Stotz, S. A., McNealy, K., Begay, R. L., DeSanto, K., Manson, S. M., & Moore, K. R. (2021). Multi-level diabetes prevention and treatment interventions for Native people in the USA and Canada: A scoping review. Current Diabetes Reports, 2 (11), 46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-021-01414-3

- PRISMA Flow Diagram Generator (ShinyApp.io, Haddaway et al. )

- PRISMA Diagram Templates (Word and PDF)

- Make a copy of the file to fill out the template

- Image can be downloaded as PDF, PNG, JPG, or SVG

- Covidence generates a PRISMA diagram that is automatically updated as records move through the review phases

8. Synthesize & Report Results

There are a number of reporting guideline available to guide the synthesis and reporting of results in systematic literature reviews.

It is common to organize findings in a matrix, also known as a Table of Evidence (ToE).

- Reporting Guidelines for Systematic Reviews

- Download a sample template of a health sciences review matrix (GoogleSheets)

Steps modified from:

Cook, D. A., & West, C. P. (2012). Conducting systematic reviews in medical education: a stepwise approach. Medical Education , 46 (10), 943–952.

- << Previous: Critical Appraisal Resources

- Next: What are Literature Reviews? >>

- Last Updated: May 31, 2024 10:32 AM

- URL: https://guides.nyu.edu/health

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Performing a...

Performing a literature review

- Related content

- Peer review

- Gulraj S Matharu , academic foundation doctor ,

- Christopher D Buckley , Arthritis Research UK professor of rheumatology

- 1 Institute of Biomedical Research, College of Medical and Dental Sciences, School of Immunity and Infection, University of Birmingham, UK

A necessary skill for any doctor

What causes disease, which drug is best, does this patient need surgery, and what is the prognosis? Although experience helps in answering these questions, ultimately they are best answered by evidence based medicine. But how do you assess the evidence? As a medical student, and throughout your career as a doctor, critical appraisal of published literature is an important skill to develop and refine. At medical school you will repeatedly appraise published literature and write literature reviews. These activities are commonly part of a special study module, research project for an intercalated degree, or another type of essay based assignment.

Formulating a question

Literature reviews are most commonly performed to help answer a particular question. While you are at medical school, there will usually be some choice regarding the area you are going to review.

Once you have identified a subject area for review, the next step is to formulate a specific research question. This is arguably the most important step because a clear question needs to be defined from the outset, which you aim to answer by doing the review. The clearer the question, the more likely it is that the answer will be clear too. It is important to have discussions with your supervisor when formulating a research question as his or her input will be invaluable. The research question must be objective and concise because it is easier to search through the evidence with a clear question. The question also needs to be feasible. What is the point in having a question for which no published evidence exists? Your supervisor’s input will ensure you are not trying to answer an unrealistic question. Finally, is the research question clinically important? There are many research questions that may be answered, but not all of them will …

Log in using your username and password

BMA Member Log In

If you have a subscription to The BMJ, log in:

- Need to activate

- Log in via institution

- Log in via OpenAthens

Log in through your institution

Subscribe from £184 *.

Subscribe and get access to all BMJ articles, and much more.

* For online subscription

Access this article for 1 day for: £33 / $40 / €36 ( excludes VAT )

You can download a PDF version for your personal record.

Buy this article

Online ordering is currently unavailable due to technical issues. We apologise for any delays responding to customers while we resolve this. For further updates please visit our website: https://www.cambridge.org/news-and-insights/technical-incident Due to planned maintenance there will be periods of time where the website may be unavailable. We apologise for any inconvenience.

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Journals

- > BJPsych Advances

- > Volume 24 Issue 2

- > How to carry out a literature search for a systematic...

Article contents

- LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- DECLARATION OF INTEREST

Defining the clinical question

Scoping search, search strategy, sources to search, developing a search strategy, searching electronic databases, supplementary search techniques, obtaining unpublished literature, conclusions, how to carry out a literature search for a systematic review: a practical guide.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 March 2018

Performing an effective literature search to obtain the best available evidence is the basis of any evidence-based discipline, in particular evidence-based medicine. However, with a vast and growing volume of published research available, searching the literature can be challenging. Even when journals are indexed in electronic databases, it can be difficult to identify all relevant studies without an effective search strategy. It is also important to search unpublished literature to reduce publication bias, which occurs from a tendency for authors and journals to preferentially publish statistically significant studies. This article is intended for clinicians and researchers who are approaching the field of evidence synthesis and would like to perform a literature search. It aims to provide advice on how to develop the search protocol and the strategy to identify the most relevant evidence for a given research or clinical question. It will also focus on how to search not only the published but also the unpublished literature using a number of online resources.

• Understand the purpose of conducting a literature search and its integral part of the literature review process

• Become aware of the range of sources that are available, including electronic databases of published data and trial registries to identify unpublished data

• Understand how to develop a search strategy and apply appropriate search terms to interrogate electronic databases or trial registries

A literature search is distinguished from, but integral to, a literature review. Literature reviews are conducted for the purpose of (a) locating information on a topic or identifying gaps in the literature for areas of future study, (b) synthesising conclusions in an area of ambiguity and (c) helping clinicians and researchers inform decision-making and practice guidelines. Literature reviews can be narrative or systematic, with narrative reviews aiming to provide a descriptive overview of selected literature, without undertaking a systematic literature search. By contrast, systematic reviews use explicit and replicable methods in order to retrieve all available literature pertaining to a specific topic to answer a defined question (Higgins Reference Higgins and Green 2011 ). Systematic reviews therefore require a priori strategies to search the literature, with predefined criteria for included and excluded studies that should be reported in full detail in a review protocol.

Performing an effective literature search to obtain the best available evidence is the basis of any evidence-based discipline, in particular evidence-based medicine (Sackett Reference Sackett 1997 ; McKeever Reference McKeever, Nguyen and Peterson 2015 ). However, with a vast and growing volume of published research available, searching the literature can be challenging. Even when journals are indexed in electronic databases, it can be difficult to identify all relevant studies without an effective search strategy (Hopewell Reference Hopewell, Clarke and Lefebvre 2007 ). In addition, unpublished data and ‘grey’ literature (informally published material such as conference abstracts) are now becoming more accessible to the public. It is important to search unpublished literature to reduce publication bias, which occurs because of a tendency for authors and journals to preferentially publish statistically significant studies (Dickersin Reference Dickersin and Min 1993 ). Efforts to locate unpublished and grey literature during the search process can help to reduce bias in the results of systematic reviews (Song Reference Song, Parekh and Hooper 2010 ). A paradigmatic example demonstrating the importance of capturing unpublished data is that of Turner et al ( Reference Turner, Matthews and Linardatos 2008 ), who showed that using only published data in their meta-analysis led to effect sizes for antidepressants that were one-third (32%) larger than effect sizes derived from combining both published and unpublished data. Such differences in findings from published and unpublished data can have real-life implications in clinical decision-making and treatment recommendation. In another relevant publication, Whittington et al ( Reference Whittington, Kendall and Fonagy 2004 ) compared the risks and benefits of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in the treatment of depression in children. They found that published data suggested favourable risk–benefit profiles for SSRIs in this population, but the addition of unpublished data indicated that risk outweighed treatment benefits. The relative weight of drug efficacy to side-effects can be skewed if there has been a failure to search for, or include, unpublished data.

In this guide for clinicians and researchers on how to perform a literature search we use a working example about efficacy of an intervention for bipolar disorder to demonstrate the search techniques outlined. However, the overarching methods described are purposefully broad to make them accessible to all clinicians and researchers, regardless of their research or clinical question.

The review question will guide not only the search strategy, but also the conclusions that can be drawn from the review, as these will depend on which studies or other forms of evidence are included and excluded from the literature review. A narrow question will produce a narrow and precise search, perhaps resulting in too few studies on which to base a review, or be so focused that the results are not useful in wider clinical settings. Using an overly narrow search also increases the chances of missing important studies. A broad question may produce an imprecise search, with many false-positive search results. These search results may be too heterogeneous to evaluate in one review. Therefore from the outset, choices should be made about the remit of the review, which will in turn affect the search.

A number of frameworks can be used to break the review question into concepts. One such is the PICO (population, intervention, comparator and outcome) framework, developed to answer clinical questions such as the effectiveness of a clinical intervention (Richardson Reference Richardson, Wilson and Nishikawa 1995 ). It is noteworthy that ‘outcome’ concepts of the PICO framework are less often used in a search strategy as they are less well defined in the titles and abstracts of available literature (Higgins Reference Higgins and Green 2011 ). Although PICO is widely used, it is not a suitable framework for identifying key elements of all questions in the medical field, and minor adaptations are necessary to enable the structuring of different questions. Other frameworks exist that may be more appropriate for questions about health policy and management, such as ECLIPSE (expectation, client group, location, impact, professionals, service) (Wildridge Reference Wildridge and Bell 2002 ) or SPICE (setting, perspective, intervention, comparison, evaluation) for service evaluation (Booth Reference Booth 2006 ). A detailed overview of frameworks is provided in Davies ( Reference Davies 2011 ).

Before conducting a comprehensive literature search, a scoping search of the literature using just one or two databases (such as PubMed or MEDLINE) can provide valuable information as to how much literature for a given review question already exists. A scoping search may reveal whether systematic reviews have already been undertaken for a review question. Caution should be taken, however, as systematic reviews that may appear to ask the same question may have differing inclusion and exclusion criteria for studies included in the review. In addition, not all systematic reviews are of the same quality. If the original search strategy is of poor quality methodologically, original data are likely to have been missed and the search should not simply be updated (compare, for example, Naughton et al ( Reference Naughton, Clarke and O'Leary 2014 ) and Caddy et al ( Reference Caddy, Amit and McCloud 2015 ) on ketamine for treatment-resistant depression).

The first step in conducting a literature search should be to develop a search strategy. The search strategy should define how relevant literature will be identified. It should identify sources to be searched (list of databases and trial registries) and keywords used in the literature (list of keywords). The search strategy should be documented as an integral part of the systematic review protocol. Just as the rest of a well-conducted systematic review, the search strategy used needs to be explicit and detailed such that it could reproduced using the same methodology, with exactly the same results, or updated at a later time. This not only improves the reliability and accuracy of the review, but also means that if the review is replicated, the difference in reviewers should have little effect, as they will use an identical search strategy. The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement was developed to standardise the reporting of systematic reviews (Moher Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff 2009 ). The PRISMA statement consists of a 27-item checklist to assess the quality of each element of a systematic review (items 6, 7 and 8 relate to the quality of literature searching) and also to guide authors when reporting their findings.

There are a number of databases that can be searched for literature, but the identification of relevant sources is dependent on the clinical or research question (different databases have different focuses, from more biology to more social science oriented) and the type of evidence that is sought (i.e. some databases report only randomised controlled trials).

• MEDLINE and Embase are the two main biomedical literature databases. MEDLINE contains more than 22 million references from more than 5600 journals worldwide. In addition, the MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations database holds references before they are published on MEDLINE. Embase has a strong coverage of drug and pharmaceutical research and provides over 30 million references from more than 8500 currently published journals, 2900 of which are not in MEDLINE. These two databases, however, are only available to either individual subscribers or through institutional access such as universities and hospitals. PubMed, developed by the National Center for Biotechnology Information of the US National Library of Medicine, provides access to a free version of MEDLINE and is accessible to researchers, clinicians and the public. PubMed comprises medical and biomedical literature indexed in MEDLINE, but provides additional access to life science journals and e-books.

In addition, there are a number of subject- and discipline-specific databases.

• PsycINFO covers a range of psychological, behavioural, social and health sciences research.

• The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) hosts the most comprehensive source of randomised and quasi-randomised controlled trials. Although some of the evidence on this register is also included in Embase and MEDLINE, there are over 150 000 reports indexed from other sources, such as conference proceedings and trial registers, that would otherwise be less accessible (Dickersin Reference Dickersin, Manheimer and Wieland 2002 ).

• The Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), British Nursing Index (BNI) and the British Nursing Database (formerly BNI with Full Text) are databases relevant to nursing, but they span literature across medical, allied health, community and health management journals.

• The Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED) is a database specifically for alternative treatments in medicine.

The examples of specific databases given here are by no means exhaustive, but they are popular and likely to be used for literature searching in medicine, psychiatry and psychology. Website links for these databases are given in Box 1 , along with links to resources not mentioned above. Box 1 also provides a website link to a couple of video tutorials for searching electronic databases. Box 2 shows an example of the search sources chosen for a review of a pharmacological intervention of calcium channel antagonists in bipolar disorder, taken from a recent systematic review (Cipriani Reference Cipriani, Saunders and Attenburrow 2016a ).

BOX 1 Website links of search sources to obtain published and unpublished literature

Electronic databases

• MEDLINE/PubMed: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed

• Embase: www.embase.com

• PsycINFO: www.apa.org/psycinfo

• Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL): www.cochranelibrary.com

• Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL): www.cinahl.com

• British Nursing Index: www.bniplus.co.uk

• Allied and Complementary Medicine Database: https://www.ebsco.com/products/research-databases/amed-the-allied-and-complementary-medicine-database

Grey literature databases

• BIOSIS Previews (part of Thomson Reuters Web of Science): https://apps.webofknowledge.com

Trial registries

• ClinicalTrials.gov: www.clinicaltrials.gov

• Drugs@FDA: www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf

• European Medicines Agency (EMA): www.ema.europa.eu

• World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP): www.who.int/ictrp

• GlaxoSmithKline Study Register: www.gsk-clinicalstudyregister.com

• Eli-Lilly clinical trial results: https://www.lilly.com/clinical-study-report-csr-synopses

Guides to further resources

• King's College London Library Services: http://libguides.kcl.ac.uk/ld.php?content_id=17678464

• Georgetown University Medical Center Dahlgren Memorial Library: https://dml.georgetown.edu/core

• University of Minnesota Biomedical Library: https://hsl.lib.umn.edu/biomed/help/nursing

Tutorial videos

• Searches in electronic databases: http://library.buffalo.edu/hsl/services/instruction/tutorials.html

• Using the Yale MeSH Analyzer tool: http://library.medicine.yale.edu/tutorials/1559

BOX 2 Example of search sources chosen for a review of calcium channel antagonists in bipolar disorder (Cipriani Reference Cipriani, Saunders and Attenburrow 2016a )

Electronic databases searched:

• MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations

For a comprehensive search of the literature it has been suggested that two or more electronic databases should be used (Suarez-Almazor Reference Suarez-Almazor, Belseck and Homik 2000 ). Suarez-Almazor and colleagues demonstrated that, in a search for controlled clinical trials (CCTs) for rheumatoid arthritis, osteoporosis and lower back pain, only 67% of available citations were found by both Embase and MEDLINE. Searching MEDLINE alone would have resulted in 25% of available CCTs being missed and searching Embase alone would have resulted in 15% of CCTs being missed. However, a balance between the sensitivity of a search (an attempt to retrieve all relevant literature in an extensive search) and the specificity of a search (an attempt to retrieve a more manageable number of relevant citations) is optimal. In addition, supplementing electronic database searches with unpublished literature searches (see ‘Obtaining unpublished literature’ below) is likely to reduce publication bias. The capacity of the individuals or review team is likely largely to determine the number of sources searched. In all cases, a clear rationale should be outlined in the review protocol for the sources chosen (the expertise of an information scientist is valuable in this process).

Important methodological considerations (such as study design) may also be included in the search strategy. Dependent on the databases and supplementary sources chosen, filters can be used to search the literature by study design (see ‘Searching electronic databases’). For instance, if the search strategy is confined to one study design term only (e.g. randomised controlled trial, RCT), only the articles labelled in this way will be selected. However, it is possible that in the database some RCTs are not labelled as such, so they will not be picked up by the filtered search. Filters can help reduce the number of references retrieved by the search, but using just one term is not 100% sensitive, especially if only one database is used (i.e. MEDLINE). It is important for systematic reviewers to know how reliable such a strategy can be and treat the results with caution.

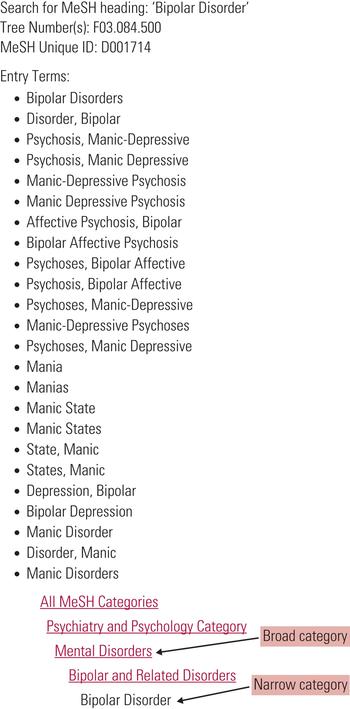

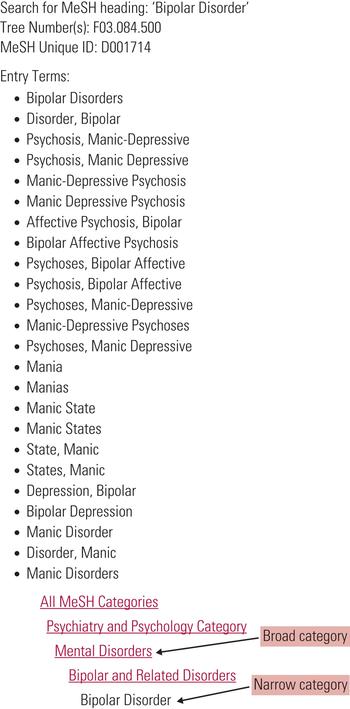

Identifying search terms

Standardised search terms are thesaurus and indexing terms that are used by electronic databases as a convenient way to categorise articles, allowing for efficient searching. Individual database records may be assigned several different standardised search terms that describe the same or similar concepts (e.g. bipolar disorder, bipolar depression, manic–depressive psychosis, mania). This has the advantage that even if the original article did not use the standardised term, when the article is catalogued in a database it is allocated that term (Guaiana Reference Guaiana, Barbui and Cipriani 2010 ). For example, an older paper might refer to ‘manic depression’, but would be categorised under the term ‘bipolar disorder’ when catalogued in MEDLINE. These standardised search terms are called MeSH (medical subject headings) in MEDLINE and PubMed, and Emtree in Embase, and are organised in a hierarchal structure ( Fig. 1 ). In both MEDLINE and Embase an ‘explode’ command enables the database to search for a requested term, as well as specific related terms. Both narrow and broader search terms can be viewed and selected to be included in the search if appropriate to a topic. The Yale MeSH Analyzer tool ( mesh.med.yale.edu ) can be used to help identify potential terms and phrases to include in a search. It is also useful to understand why relevant articles may be missing from an initial search, as it produces a comparison grid of MeSH terms used to index each article (see Box 1 for a tutorial video link).

FIG 1 Search terms and hierarchical structure of MeSH (medical subject heading) in MEDLINE and PubMed.

In addition, MEDLINE also distinguishes between MeSH headings (MH) and publication type (PT) terms. Publication terms are less about the content of an article than about its type, specifying for example a review article, meta-analysis or RCT.

Both MeSH and Emtree have their own peculiarities, with variations in thesaurus and indexing terms. In addition, not all concepts are assigned standardised search terms, and not all databases use this method of indexing the literature. It is advisable to check the guidelines of selected databases before undertaking a search. In the absence of a MeSH heading for a particular term, free-text terms could be used.

Free-text terms are used in natural language and are not part of a database’s controlled vocabulary. Free-text terms can be used in addition to standardised search terms in order to identify as many relevant records as possible (Higgins Reference Higgins and Green 2011 ). Using free-text terms allows the reviewer to search using variations in language or spelling (e.g. hypomani* or mania* or manic* – see truncation and wildcard functions below and Fig. 2 ). A disadvantage of free-text terms is that they are only searched for in the title and abstracts of database records, and not in the full texts, meaning that when a free-text word is used only in the body of an article, it will not be retrieved in the search. Additionally, a number of specific considerations should be taken into account when selecting and using free-text terms:

• synonyms, related terms and alternative phrases (e.g. mood instability, affective instability, mood lability or emotion dysregulation)

• abbreviations or acronyms in medical and scientific research (e.g. magnetic resonance imaging or MRI)

• lay and medical terminology (e.g. high blood pressure or hypertension)

• brand and generic drug names (e.g. Prozac or fluoxetine)

• variants in spelling (e.g. UK English and American English: behaviour or behavior; paediatric or pediatric).

FIG 2 Example of a search strategy about bipolar disorder using MEDLINE (Cipriani Reference Cipriani, Saunders and Attenburrow 2016a ). The strategy follows the PICO framework and includes MeSH terms, free-text keywords and a number of other techniques, such as truncation, that have been outlined in this article. Numbers in bold give the number of citations retrieved by each search.

Truncation and wildcard functions can be used in most databases to capture variations in language:

• truncation allows the stem of a word that may have variant endings to be searched: for example, a search for depress* uses truncation to retrieve articles that mention both depression and depressive; truncation symbols may vary by database, but common symbols include: *, ! and #

• wild cards substitute one letter within a word to retrieve alternative spellings: for example, ‘wom?n’ would retrieve the terms ‘woman’ and ‘women’.

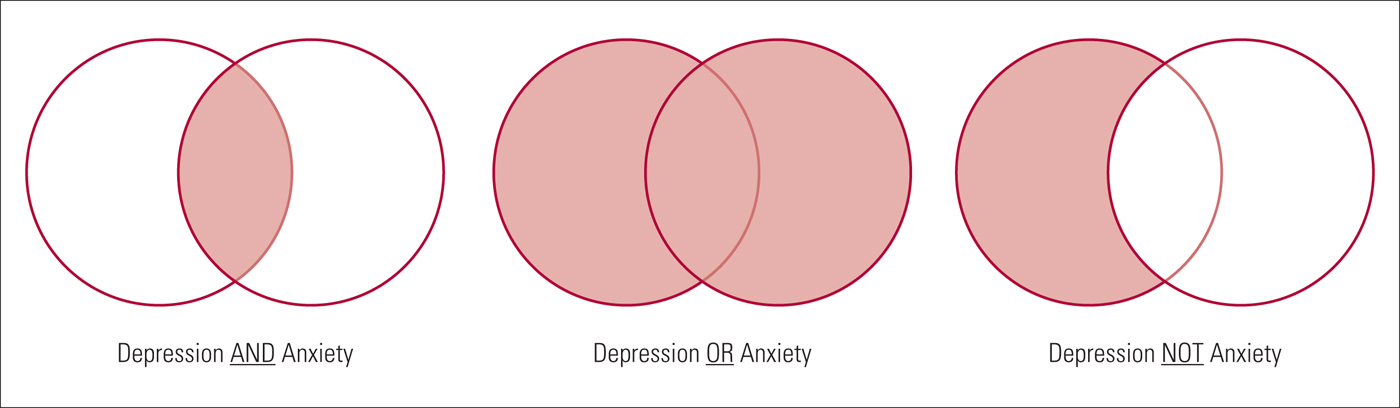

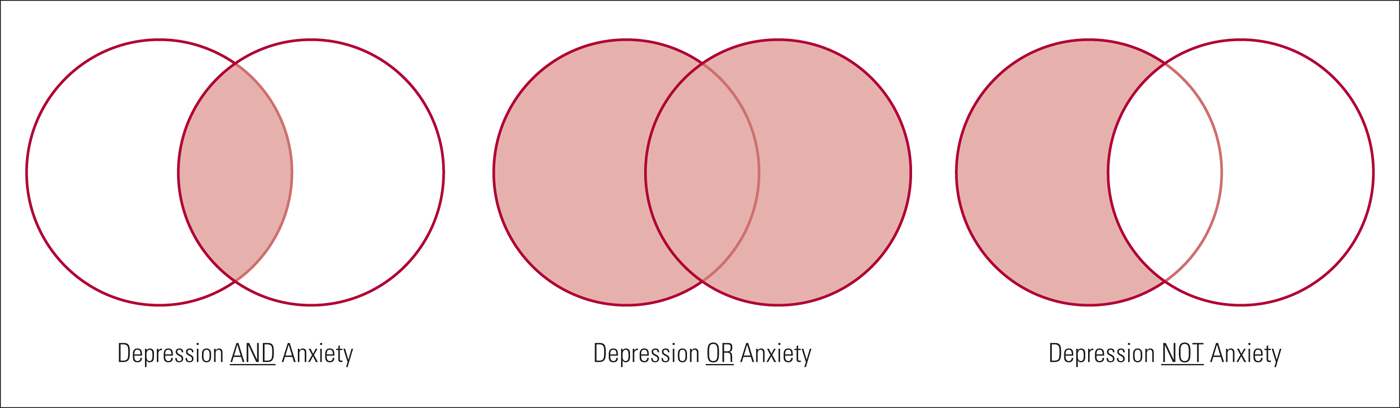

Combining search terms

Search terms should be combined in the search strategy using Boolean operators. Boolean operators allow standardised search terms and free-text terms to be combined. There are three main Boolean operators – AND, OR and NOT ( Fig. 3 ).

• OR – this operator is used to broaden a search, finding articles that contain at least one of the search terms within a concept. Sets of terms can be created for each concept, for example the population of interest: (bipolar disorder OR bipolar depression). Parentheses are used to build up search terms, with words within parentheses treated as a unit.

• AND – this can be used to join sets of concepts together, narrowing the retrieved literature to articles that contain all concepts, for example the population or condition of interest and the intervention to be evaluated: (bipolar disorder OR bipolar depression) AND calcium channel blockers. However, if at least one term from each set of concepts is not identified from the title or abstract of an article, this article will not be identified by the search strategy. It is worth mentioning here that some databases can run the search also across the full texts. For example, ScienceDirect and most publishing houses allow this kind of search, which is much more comprehensive than abstract or title searches only.

• NOT – this operator, used less often, can focus a search strategy so that it does not retrieve specific literature, for example human studies NOT animal studies. However, in certain cases the NOT operator can be too restrictive, for example if excluding male gender from a population, using ‘NOT male’ would also mean that any articles about both males and females are not obtained by the search.

FIG 3 Example of Boolean operator concepts (the resulting search is the light red shaded area).

The conventions of each database should be checked before undertaking a literature search, as functions and operators may differ slightly between them (Cipriani Reference Cipriani, Saunders and Attenburrow 2016b ). This is particularly relevant when using limits and filters. Figure 2 shows an example search strategy incorporating many of the concepts described above. The search strategy is taken from Cipriani et al ( Reference Cipriani, Zhou and Del Giovane 2016a ), but simplified to include only one intervention.

Search filters

A number of filters exist to focus a search, including language, date and study design or study focus filters. Language filters can restrict retrieval of articles to the English language, although if language is not an inclusion criterion it should not be restricted, to avoid language bias. Date filters can be used to restrict the search to literature from a specified period, for example if an intervention was only made available after a certain date. In addition, if good systematic reviews exist that are likely to capture all relevant literature (as advised by an information specialist), date restrictions can be used to search additional literature published after the date of that included in the systematic review. In the same way, date filters can be used to update a literature search since the last time it was conducted. Reviewing the literature should be a timely process (new and potentially relevant evidence is produced constantly) and updating the search is an important step, especially if collecting evidence to inform clinical decision-making, as publications in the field of medicine are increasing at an impressive rate (Barber Reference Barber, Corsi and Furukawa 2016 ). The filters chosen will depend on the research question and nature of evidence that is sought through the literature search and the guidelines of the individual database that is used.

- Google Scholar

Google Scholar allows basic Boolean operators to be used in strings of search terms. However, the search engine does not use standardised search terms that have been tagged as in traditional databases and therefore variations of keywords should always be searched. There are advantages and disadvantages to using a web search engine such as Google Scholar. Google Scholar searches the full text of an article for keywords and also searches a wider range of sources, such as conference proceedings and books, that are not found in traditional databases, making it a good resource to search for grey literature (Haddaway Reference Haddaway, Collins and Coughlin 2015 ). In addition, Google Scholar finds articles cited by other relevant articles produced in the search. However, variable retrieval of content (due to regular updating of Google algorithms and the individual's search history and location) means that search results are not necessarily reproducible and are therefore not in keeping with replicable search methods required by systematic reviews. Google Scholar alone has not been shown to retrieve more literature than other traditional databases discussed in this article and therefore should be used in addition to other sources (Bramer Reference Bramer, Giustini and Kramer 2016 ).

Citation searching

Once the search strategy has identified relevant literature, the reference lists in these sources can be searched. This is called citation searching or backward searching, and it can be used to see where particular research topics led others. This method is particularly useful if the search identifies systematic reviews or meta-analyses of a similar topic.

Conference abstracts

Conference abstracts are considered ‘grey literature’, i.e. literature that is not formally published in journals or books (Alberani Reference Alberani, De Castro Pietrangeli and Mazza 1990 ). Scherer and colleagues found that only 52.6% of all conference abstracts go on to full publication of results, and factors associated with publication were studies that had RCT designs and the reporting of positive or significant results (Scherer Reference Scherer, Langenberg and von Elm 2007 ). Therefore, failure to search relevant grey literature might miss certain data and bias the results of a review. Although conference abstracts are not indexed in most major electronic databases, they are available in databases such as BIOSIS Previews ( Box 1 ). However, as with many unpublished studies, these data did not undergo the peer review process that is often a tool for assessing and possibly improving the quality of the publication.

Searching trial registers and pharmaceutical websites

For reviews of trial interventions, a number of trial registers exist. ClinicalTrials.gov ( clinicaltrials.gov ) provides access to information on public and privately conducted clinical trials in humans. Results for both published and unpublished studies can be found for many trials on the register, in addition to information about studies that are ongoing. Searching each trial register requires a slightly different search strategy, but many of the basic principles described above still apply. Basic searches on ClinicialTrials.gov include searching by condition, specific drugs or interventions and these can be linked using Boolean operators: for example, (bipolar disorder OR manic depressive disorder) AND lithium. As mentioned above, parentheses can be used to build up search terms. More advanced searches allow one to specify further search fields such as the status of studies, study type and age of participants. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) hosts a database providing information about FDA-approved drugs, therapeutic products and devices ( www.fda.gov ). The database (with open access to anyone, not only in the USA) can be searched by the drug name, its active ingredient or its approval application number and, for most drugs approved in the past 20 years or so, a review of clinical trial results (some of which remain unpublished) used as evidence in the approval process is available. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) hosts a similar register for medicines developed for use in the European Union ( www.ema.europa.eu ). An internet search will show that many other national and international trial registers exist that, depending on the review question, may be relevant search sources. The World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP; www.who.int/ictrp ) provides access to a central database bringing a number of these national and international trial registers together. It can be searched in much the same way as ClinicalTrials.gov.

A number of pharmaceutical companies now share data from company-sponsored clinical trials. GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) is transparent in the sharing of its data from clinical studies and hosts its own clinical study register ( www.gsk-clinicalstudyregister.com ). Eli-Lilly provides clinical trial results both on its website ( www.lillytrialguide.com ) and in external registries. However, other pharmaceutical companies, such as Wyeth and Roche, divert users to clinical trial results in external registries. These registries include both published and previously unpublished studies. Searching techniques differ for each company and hand-searching through documents is often required to identify studies.

Communication with authors

Direct communication with authors of published papers could produce both additional data omitted from published studies and other unpublished studies. Contact details are usually available for the corresponding author of each paper. Although high-quality reviews do make efforts to obtain and include unpublished data, this does have potential disadvantages: the data may be incomplete and are likely not to have been peer-reviewed. It is also important to note that, although reviewers should make every effort to find unpublished data in an effort to minimise publication bias, there is still likely to remain a degree of this bias in the studies selected for a systematic review.

Developing a literature search strategy is a key part of the systematic review process, and the conclusions reached in a systematic review will depend on the quality of the evidence retrieved by the literature search. Sources should therefore be selected to minimise the possibility of bias, and supplementary search techniques should be used in addition to electronic database searching to ensure that an extensive review of the literature has been carried out. It is worth reminding that developing a search strategy should be an iterative and flexible process (Higgins Reference Higgins and Green 2011 ), and only by conducting a search oneself will one learn about the vast literature available and how best to capture it.

Acknowledgements

We thank Sarah Stockton for her help in drafting this article. Andrea Cipriani is supported by the NIHR Oxford cognitive health Clinical Research Facility.

Select the single best option for each question stem

a an explicit and replicable method used to retrieve all available literature pertaining to a specific topic to answer a defined question

b a descriptive overview of selected literature

c an initial impression of a topic which is understood more fully as a research study is conducted

d a method of gathering opinions of all clinicians or researchers in a given field

e a step-by-step process of identifying the earliest published literature through to the latest published literature.

a does not need to be specified in advance of a literature search

b does not need to be reported in a systematic literature review

c defines which sources of literature are to be searched, but not how a search is to be carried out

d defines how relevant literature will be identified and provides a basis for the search strategy

e provides a timeline for searching each electronic database or unpublished literature source.

a the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

d the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL)

e the British Nursing Index.

a bipolar disorder OR treatment

b bipolar* OR treatment

c bipolar disorder AND treatment

d bipolar disorder NOT treatment

e (bipolar disorder) OR (treatment).

a publication bias

b funding bias

c language bias

d outcome reporting bias

e selection bias.

MCQ answers

1 a 2 d 3 b 4 c 5 a

FIG 2 Example of a search strategy about bipolar disorder using MEDLINE (Cipriani 2016a). The strategy follows the PICO framework and includes MeSH terms, free-text keywords and a number of other techniques, such as truncation, that have been outlined in this article. Numbers in bold give the number of citations retrieved by each search.

This article has been cited by the following publications. This list is generated based on data provided by Crossref .

View all Google Scholar citations for this article.

Save article to Kindle

To save this article to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

- Volume 24, Issue 2

- Lauren Z. Atkinson and Andrea Cipriani

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1192/bja.2017.3

Save article to Dropbox

To save this article to your Dropbox account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Dropbox account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save article to Google Drive

To save this article to your Google Drive account, please select one or more formats and confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you used this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your Google Drive account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Reply to: Submit a response

- No HTML tags allowed - Web page URLs will display as text only - Lines and paragraphs break automatically - Attachments, images or tables are not permitted

Your details

Your email address will be used in order to notify you when your comment has been reviewed by the moderator and in case the author(s) of the article or the moderator need to contact you directly.

You have entered the maximum number of contributors

Conflicting interests.

Please list any fees and grants from, employment by, consultancy for, shared ownership in or any close relationship with, at any time over the preceding 36 months, any organisation whose interests may be affected by the publication of the response. Please also list any non-financial associations or interests (personal, professional, political, institutional, religious or other) that a reasonable reader would want to know about in relation to the submitted work. This pertains to all the authors of the piece, their spouses or partners.

The “PP-ICONS” approach will help you separate the clinical wheat from the chaff in mere minutes .

ROBERT J. FLAHERTY, MD

Fam Pract Manag. 2004;11(5):47-52

Keeping up with the latest advances in diagnosis and treatment is a challenge we all face as phycians. We need information that is both valid (that is, accurate and correct) and relevant to our patients and practices. While we have many sources of clinical information, such as CME lectures, textbooks, pharmaceutical advertising, pharmaceutical representatives and colleagues, we often turn to journal articles for the most current clinical information.

Unfortunately, a great deal of research reported in journal articles is poorly done, poorly analyzed or both, and thus is not valid. A great deal of research is also irrelevant to our patients and practices. Separating the clinical wheat from the chaff can take skills that many of us never were taught.

Reading the abstract is often sufficient when evaluating an article using the PP-ICONS approach.

The most relevant studies will involve outcomes that matter to patients (e.g., morbidity, mortality and cost) versus outcomes that matter to physiologists (e.g., blood pressure, blood sugar or cholesterol levels).

Ignore the relative risk reduction, as it overstates research findings and will mislead you.

The article “Making Evidence-Based Medicine Doable in Everyday Practice” in the February 2004 issue of FPM describes several organizations that can help us. These organizations, such as the Cochrane Library, Bandolier and Clinical Evidence, develop clinical questions and then review one or more journal articles to identify the best available evidence that answers the question, with a focus on the quality of the study, the validity of the results and the relevance of the findings to everyday practice. These organizations provide a very valuable service, and the number of important clinical questions that they have studied has grown steadily over the past five years. (See “Four steps to an evidence-based answer.” )

FOUR STEPS TO AN EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER

When faced with a clinical question, follow these steps to find an evidence-based answer:

Search the Web site of one of the evidence review organizations, such as Cochrane (http://www.cochrane.org/cochrane/revabstr/mainindex.htm), Bandolier ( http://www.jr2.ox.ac.uk/bandolier ) or Clinical Evidence ( http://www.clinicalevidence.com ), described in “Making Evidence-Based Medicine Doable in Everyday Practice,” FPM, February 2004, page 51 . You can also search the TRIP+ Web site ( http://www.tripdatabase.com ), which simultaneously searches the databases of many of the review organizations. If you find a systematic review or meta-analysis by one of these organizations, you can be confident that you’ve found the best evidence available.

If you don’t find the information you need through step 1, search for meta-analyses and systematic reviews using the PubMed Web site (see the tutorial at http://www.nlm.nih.gov/bsd/pubmed_tutorial/m1001.html ). Most of the recent abstracts found on PubMed provide enough information for you to determine the validity and relevance of the findings. If needed, you can get a copy of the full article through your hospital library or the journal’s Web site.

If you cannot find a systematic review or meta-analysis on PubMed, look for a randomized controlled trial (RCT). The RCT is the “gold standard” in medical research. Case reports, cohort studies and other research methods simply are not good enough to use for making patient care decisions.

Once you find the article you need, use the PP-ICONS approach to evaluate its usefulness to your patient.

If you find a systematic review or meta-analysis done by one of these organizations, you can feel confident that you have found the current best evidence. However, these organizations have not asked all of the common clinical questions yet, and you will frequently be faced with finding the pertinent articles and determining for yourself whether they are valuable. This is where the PP-ICONS approach can help.

What is PP-ICONS?

When you find a systematic review, meta-analysis or randomized controlled trial while reading your clinical journals or searching PubMed ( http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi ), you need to determine whether it is valid and relevant. There are many different ways to analyze an abstract or journal article, some more rigorous than others. 1 , 2 I have found a simple but effective way to identify a valid or relevant article within a couple of minutes, ensuring that I can use or discard the conclusions with confidence. This approach works well on articles regarding treatment and prevention, and can also be used with articles on diagnosis and screening.

The most important information to look for when reviewing an article can be summarized by the acronym “PP-ICONS,” which stands for the following:

Patient or population,

Intervention,

Comparison,

Number of subjects,

Statistics.

For example, imagine that you just saw a nine-year-old patient in the office with common warts on her hands, an ideal candidate for your usual cryotherapy. Her mother had heard about treating warts with duct tape and wondered if you would recommend this treatment. You promised to call Mom back after you had a chance to investigate this rather odd treatment.

When you get a free moment, you write down your clinical question: “Is duct tape an effective treatment for warts in children?” Writing down your clinical question is useful, as it can help you clarify exactly what you are looking for. Use the PPICO parts of the acronym to help you write your clinical question; this is actually how many researchers develop their research questions.

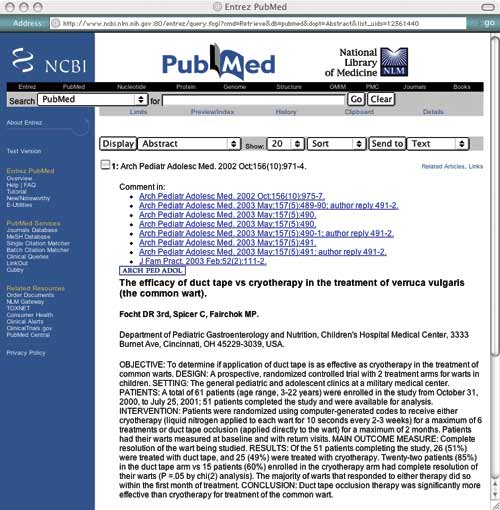

You search Cochrane and Bandolier without success, so now you search PubMed, which returns an abstract for the following article: “Focht DR 3rd, Spicer C, Fairchok MP. The efficacy of duct tape vs cryotherapy in the treatment of verruca vulgaris (the common wart). Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med . 2002 Oct;156(10):971-974.”

You decide to apply PP-ICONS to this abstract (see "Abstract from PubMed" ) to determine if the information is both valid and relevant.

ABSTRACT FROM PUBMED

Using the PP-ICONS approach, physicians can evaluate the validity and relevance of clinical articles in minutes using only the abstract, such as this one, obtained free online from PubMed, http://www.ncbi. nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi. The author uses this abstract to evaluate the use of duct tape to treat common warts.

Problem. The first P in PP-ICONS is for “problem,” which refers to the clinical condition that was studied. From the abstract, it is clear that the researchers studied the same problem you are interested in, which is important since flat warts or genital warts may have responded differently. Obviously, if the problem studied were not sufficiently similar to your clinical problem, the results would not be relevant.

Patient or population. Next, consider the patient or population. Is the study group similar to your patient or practice? Are they primary care patients, for example, or are they patients who have been referred to a tertiary care center? Are they of a similar age and gender? In this case, the researchers studied children and young adults in outpatient clinics, which is similar to your patient population. If the patients in the study are not similar to your patient, for example if they are sicker, older, a different gender or more clinically complicated, the results might not be relevant.

Intervention. The intervention could be a diagnostic test or a treatment. Make sure the intervention is the same as what you are looking for. The patient’s mother was asking about duct tape for warts, so this is a relevant study.

Comparison. The comparison is what the intervention is tested against. It could be a different diagnostic test or another therapy, such as cryotherapy in this wart study. It could even be placebo or no treatment. Make sure the comparison fits your question. You usually use cryotherapy for common warts, so this is a relevant comparison.

Outcome. The outcome is particularly important. Many outcomes are “disease-oriented outcomes,” which are based on “disease-oriented evidence” (DOEs). DOEs usually reflect changes in physiologic parameters, such as blood pressure, blood sugar, cholesterol, etc. We have long assumed that improving the physiologic parameters of a disease will result in a better disease outcome, but that is not necessarily true. For instance, finasteride can improve urinary flow rate in prostatic hypertrophy, but it does not significantly change symptom scores. 3

DOEs look at the kinds of outcomes that physiologists care about. More relevant are outcomes that patients care about, often called “patient-oriented outcomes.” These are based on “patient-oriented evidence that matters” (POEMs) and look at outcomes such as morbidity, mortality and cost. Thus, when looking at a journal article, DOEs are interesting but of questionable relevance, whereas POEMs are very interesting and very relevant. In the study on the previous page, the outcome is complete resolution of the wart, which is something your patient is interested in.

Number. The number of subjects is crucial to whether accurate statistics can be generated from the data. Too few patients in a research study may not be enough to show that a difference actually exists between the intervention and comparison groups (known as the “power” of a study). Many studies are published with less than 100 subjects, which is usually inadequate to provide reliable statistics. A good rule of thumb is 400 subjects. 4 Fifty-one patients completed the wart study, which is a pretty small number to generate good statistics.

Statistics. The statistics you are interested in are few in number and easy to understand. Since statistics are frequently misused in journal articles, it is worth a few minutes to learn which to believe and which to ignore.

Relative risk reduction. It is not unusual to find a summary statement in a journal article similar to this one from an article titled “Long-Term Effects of Mammography Screening: Updated Overview of the Swedish Randomised Trials”: 5

“There were 511 breast cancer deaths in 1,864,770 women-years in the invited groups and 584 breast cancer deaths in 1,688,440 women-years in the control groups, a significant 21 percent reduction in breast cancer mortality.”

This 21-percent statistic is the relative risk reduction (RRR), which is the percent reduction in the measured outcome between the experimental and control groups. (See “Some important statistics” for more information on calculating the RRR and other statistics.) The RRR is not a good way to compare outcomes. It amplifies small differences and makes insignificant findings appear significant, and it doesn’t reflect the baseline risk of the outcome event. Nevertheless, the RRR is very popular and will be reported in nearly every journal article, perhaps because it makes weak results look good. Think of the RRR as the “reputation reviving ratio” or the “reporter’s reason for ‘riting.” Ignore the RRR. It will mislead you. In our wart treatment example, the RRR would be (85 percent - 60 percent)/60 percent x 100 = 42 percent. The RRR could thus be interpreted as showing that duct tape is 42 percent more effective than cryotherapy in treating warts.

SOME IMPORTANT STATISTICS

Absolute risk reduction (ARR): The difference between the control group’s event rate (CER) and the experimental group’s event rate (EER).

Control event rate (CER): The proportion of patients responding to placebo or other control treatment. For example, if 25 patients are in a control group and the event being studied is observed in 15 of those patients, the control event rate would be 15/25 = 0.60.

Experimental event rate (EER): The proportion of patients responding to the experimental treatment or intervention. For example, if 26 patients are in an experimental group and the event being studied is observed in 22 of those patients, the experimental event rate would be 22/26 = 0.85.

Number needed to treat (NNT): The number of patients that must be treated to prevent one adverse outcome or for one patient to benefit. The NNT is the inverse of the ARR; NNT = 1/ARR.

Relative risk reduction (RRR): The percent reduction in events in the treated group compared to the control group event rate.

| When the experimental treatment reduces the risk of a bad event: | Example: Beta-blockers to prevent deaths in high-risk patients with recent myocardial infarction: | When the experimental treatment increases the probability of a good event: | Example: Duct tape to eliminate common warts. | |

| Relative risk reduction (RRR) | CER-EER/CER | (.66 -. 50)/.66 = .24 or 24 percent | EER-CER/CER | (.85-.60)/.60 = .42 or 42 percent |

| Absolute risk reduction (ARR): | CER-EER | (.66 - .50) = .16 or 16 percent | EER-CER | .85-.60 = .25 or 25 percent |

| Number needed to treat (NNT) | 1/ARR | 1/.16 = 6 | 1/ARR | 1/.25 = 4 |

Absolute risk reduction. A better statistic is the absolute risk reduction (ARR), which is the difference in the outcome event rate between the control group and the experimental treated group. Thus, in our wart treatment example, the ARR is the outcome event rate (complete resolution of warts) for duct tape (85 percent) minus the outcome event rate for cryotherapy (60 percent) = 25 percent. Unlike the RRR, the ARR does not amplify small differences but shows the true difference between the experimental and control interventions. Using the ARR, it would be accurate to say that duct tape is 25-percent more effective than cryotherapy in treating warts.

Number needed to treat. The single most clinically useful statistic is the number needed to treat (NNT). The NNT is the number of patients who must be treated to prevent one adverse outcome. To think about it another way, the NNT is the number of patients who must be treated for one patient to benefit. (The rest who were treated obtained no benefit, although they still suffered the risks and costs of treatment.) In our wart therapy article, the NNT would tell us how many patients must be treated with the experimental treatment for one to benefit more than if he or she had been treated with the standard treatment.

Now this is a statistic that physicians and their patients can really appreciate! Furthermore, the NNT is easy to calculate, as it is simply the inverse of the ARR. For our wart treatment study, the NNT is 1/25 percent =1/0.25 = 4, meaning that 4 patients need to be treated with duct tape for one to benefit more than if treated by cryotherapy.

Wrapped up in this simple little statistic are some very important concepts. The NNT provides you with the likelihood that the test or treatment will benefit any individual patient, an impression of the baseline risk of the adverse event, and a sense of the cost to society. Thus, it gives perspective and hints at the “reasonableness” of a treatment. The value of this statistic has become appreciated in the last five years, and more journal articles are reporting it.