- Skip to main document

- Skip to site search

- Skip to main site navigation

- Enlarge Text

- Reduce Text

Writing Assessment: A Position Statement

Conference on College Composition and Communication November 2006 (revised March 2009, reaffirmed November 2014, revised April 2022)

Introduction

Writing assessment can be used for a variety of purposes, both inside the classroom and outside: supporting student learning, assigning a grade, placing students in appropriate courses, allowing them to exit a course or sequence of courses, certifying proficiency, and evaluating programs. Given the high-stakes nature of many of these assessment purposes, it is crucial that assessment practices be guided by sound principles that are fair and just and specific to the people for whom and the context and purposes for which they are designed. This position statement aims to provide that guidance for writing teachers and administrators across institutional types and missions.

We encourage faculty, administrators, students, community members, and other stakeholders to reflect on the ways the principles, considerations, and practices articulated in this document are present in their current assessment methods and to consider revising and rethinking their practices to ensure that inclusion and language diversity, teaching and learning, and ethical labor practices inform every level of writing assessment.

Foundational Principles of Writing Assessment

This position statement identifies six principles that form the ethical foundation of writing assessment.

- Writing assessments are important means for guiding teaching and learning. Writing assessments—and assignments to which they correlate—should be designed and implemented in pursuit of clearly articulated learning goals.

- The methods and criteria used to assess writing shape student perceptions of writing and of themselves as writers.

- Assessment practices should be solidly grounded in the latest research on learning, literacies, language, writing, equitable pedagogy, and ethical assessment.

- Writing is by definition social. In turn, assessing writing is social. Teaching writing and learning to write entail exploring a range of purposes, audiences, social and cultural contexts and positions, and mediums.

- Writers approach their writing with different attitudes, experiences, and language practices. Writers deserve the opportunity to think through and respond to numerous rhetorical situations that allow them to incorporate their knowledges, to explore the perspectives of others, and to set goals for their writing and their ongoing development as writers.

- Writing and writing assessment are labor-intensive practices. Labor conditions and outcomes must be designed and implemented in pursuit of both the short-term and long-term health and welfare of all participants.

Considerations for Designing Writing Assessments

Based on the six foundational principles detailed in the previous section, this section enumerates key considerations that follow from these principles for the design, interpretation, and implementation of writing assessments, whether formative or summative or at the classroom or programmatic level.

Considerations for Inclusion and Language Diversity

- Best assessment practice is contextual. It is designed and implemented to address the learning needs of a full range of students in the local context, and involves methods and criteria that are locally developed, deriving from the particular context and purposes for the writing being assessed. (1, 2)

- Best assessment practice requires that learning goals, assessment methods, and criteria for success be equitable, accessible, and appropriate for each student in the local context . To meet this requirement, assessments are informed by research focused on the ways assignments and varied forms of assessment affect diverse student groups. (3)

- Best assessment practice recognizes that mastery is not necessarily an indicator of excellence . It provides opportunities for students to demonstrate their strengths in writing, displaying the strategies or skills taught in the relevant environment. Successful summative and formative assessment empowers students to make informed decisions about how to meet their goals as writers. (4, 5)

- Best assessment practice respects language as complicated and diverse and acknowledges that as purposes vary, criteria will as well. Best assessment practices provide multiple paths to success, accounting for a range of diverse language users, and do not arbitrarily or systematically punish linguistic differences. (3, 4, 5)

Considerations for Learning and Teaching

- Best assessment practice engages students in contextualized, meaningful writing. Strong assessments strive to set up writing tasks and situations that identify purposes that are appropriate to, and that appeal to, the particular students being assessed. (4, 5)

- Best assessment practice clearly communicates what is valued and expected of writing practices. It focuses on measuring specific outcomes defined within the program or course. Values, purposes, and learning goals should drive assessment, not the reverse. (1, 6)

- Best assessment practice relies on new developments to shape assessment methods that prioritize student learning. Best assessment practice evolves. Revisiting and revising assessment practices should be considered periodically, as research in the field develops and evolves, and/or as the assessment needs or circumstances change. (3)

- Best assessment practice engages students in the assessment process, contextualizing the method and purpose of the assessment for students and all other stakeholders. Where possible, these practices invite students to help develop assessment strategies, both formative and summative. Best assessment practice understands that students need multiple opportunities to provide feedback to and receive feedback from other learners. (2, 4, 5)

- Best assessment practice helps students learn to examine and evaluate their own writing and how it functions and moves outside of specifically defined writing courses. These practices help students set individualized goals and encourage critical reflection by student writers on their own writing processes and performances. (4, 5)

- Best assessment practice generates data which is shared with faculty and administrators in the program so that assessment results may be used to make changes in practice. These practices make use of assessment data to provide opportunities for reflection, professional development, and for the exchange of information about student performance and institutional or programmatic expectations. (1, 6)

Considerations for Labor

- Best assessment practice is undertaken in response to local goals and the local community of educators who guide the design and implementation of the assessment process. These practices actively seek feedback on assessment design and from the full range of faculty who will be impacted by or involved with the assessment process. Best assessment practice values individual writing programs, institutions, or consortiums as communities of interpreters whose knowledge of context and purpose is integral to assessment. (1, 6)

- Best assessment practice acknowledges how labor practices determine assessment implementation. It acknowledges the ways teachers’ institutional labor practices vary widely and responds to local labor demands that set realistic and humane expectations for equitable summative and formative feedback. (4, 6)

- Best assessment practice acknowledges the labor of research and the ways local conditions affect opportunities for staying abreast of the field. In these practices, opportunities for professional development based on assessment data are made accessible and meaningful to the full range of faculty teaching in the local context. (3)

- Best assessment practice uses multiple measures to ensure successful formative and summative assessment appropriate to program expectation and considers competing tensions such as teaching load, class size, and programmatic learning outcomes when determining those measures. (2, 6)

- Best assessment practice provides faculty with financial, technical, and practical support in implementing comprehensive assessment measures and acknowledges the ways local contexts influence assessment decisions. (5, 6)

Contexts for Writing Assessment

Ethical assessment at all levels and in all settings is context specific and labor intensive. Participants working toward an ethical culture of assessment must critically consider the condi tions of labor, as well as expectations for class size, participation in programmatic assessment (especially for contingent faculty members), and professional development related to assessment. In addition, these activities and expectations should inform all discussions of workload for assessment participants to ensure that the labor of assessment is appropriately recognized and, where appropriate, compensated.

Ethical assessment does not only consider the immediate practice of faculty engaging in classroom, programmatic, or institutional assessment, but it also builds on the assessment practices students have experienced in the past. Ethical assessment considers how it will coincide with other assessment practices students encounter at our institutions and keeps in sight the assessment experiences students are likely to experience in the future. A deliberately designed culture of assessment aligns classroom learning goals with larger programmatic and institutional learning goals and aligns assessment practices accordingly. It involves teachers, administrators, students, and community stakeholders designing assessments grounded in classroom and program contexts, and it includes feeding assessment data back to those involved so that assessment results may be used to make changes in practice. Ethical assessment also protects the data and identities of participants. Finally, ethical assessment practices involve asking difficult questions about the values and missions of an assignment, a course, or a program and whether or not assessments promote or possibly inhibit equity among participants.

Admissions, Placement, and Proficiency

Admissions, placement, and proficiency-based assessment practices are high-stakes processes with a history of exclusion and academic gatekeeping. Educational institutions and programs should recognize the history of these types of measures in privileging some students and penalizing others as it relates to their distinctive institutional and programmatic missions. They should then use that historical knowledge to inform the development of assessment measures that serve local needs and contexts. Assessments should be designed and implemented to support student progress and success. With placement in particular, institutions should be mindful of the financial burden and persistence issues that increase in proportion to the number of developmental credit hours students are asked to complete based on assessments.

Whether for admissions, placement, or proficiency, recommended practices for any assessment that seeks to directly measure students’ writing abilities involve, but are not limited to, the following concerns:

- Writing tasks and assessment criteria should be informed and motivated by the goals of the institution, the program, the curriculum, and the student communities that the program serves. (1, 2)

- Writing products should be measured against a clearly defined set of criteria developed in conversation with instructors of record to ensure the criteria align with the goals of the program and/or the differences between the courses into which students might be placed. (1, 2)

- Instructors of record should serve as scorers or should be regularly invited to provide feedback on whether existing assessment models are accurate, appropriate, and ethical. (4, 6)

- Assessments should consist of multiple writing tasks that allow students to engage in various stages of their writing processes. (4, 5)

- Assessment processes should include student input, whether in the form of a reflective component of the assessment or through guided self-placement measures. (5)

- Students should have the opportunity to question and appeal assessment decisions. (5, 6)

- Writing tasks and assessment criteria should be revisited regularly and updated to reflect the evolving goals of the program or curriculum. (1, 3)

Classroom Assessment

Classroom assessment processes typically involve summative and formative assessment of individually and collaboratively authored projects in both text-based and multimedia formats. Assessments in the classroom usually involve evaluations and judgments of student work. Those judgments have too often been tied to how well students perform standard edited American English (SEAE) to the exclusion of other concerns. Instead, classroom assessments should focus on acknowledging that students enter the classroom with varied language practices, abilities, and knowledges, and these enrich the classroom and create more democratic classroom spaces. Classroom assessments should reinforce and reflect the goals of individual and collaborative projects. Additionally, classroom assessment might work toward centering labor-based efforts students put forth when composing for multiple scenarios and purposes. Each of the six foundational principles of assessment is key to ensuring ethical assessment of student writing in a classroom context.

Recommended practices in classroom assessment involve, but are not limited to, the following:

- Clear communications related to the purposes of assessment for each project (1, 2)

- Assessment/feedback that promote and do not inhibit opportunities for revision, risk-taking, and play (4, 5)

- Assessment methodologies grounded in the latest research (3)

- Practices designed to benefit the health and welfare of all participants by respecting the labor of instructors and students (6)

- Occasions to illustrate a range of rhetorical skills and literacies (3, 4)

- Attention to the value of language diversity and rejection of evaluations of language based on a single standard (5)

- Efforts to demystify writing, composing, and languaging processes (3, 4)

- Opportunities for self-assessment, informed goal setting, and growth (5, 6)

- Input from the classroom community on classroom assessment processes (5, 6)

Program Assessment

Assessment of writing programs, from first-year composition programs to Writing Across the Curriculum programs, is a critical component of an institution’s culture of assessment. Assessment can focus on the operation of the program, its effectiveness to improve student writing, and how it best supports university goals.

While programmatic assessment might be driven by state or institutional policies, members of writing programs are in the best position to guide decisions about what assessments will best serve that community. Programs and departments should see themselves as communities of professionals whose assessment activities communicate measures of effectiveness to those inside and outside the program.

Writing program assessments and designs are encouraged to adhere to the following recommended practices:

- Reflect the goals and mission of the institution and its writing programs. (1)

- Draw on multiple methods, quantitative and qualitative, to assess programmatic effectiveness and incorporate blind assessment processes of anonymized writing when possible. (1, 3, 6)

- Establish shared assessment criteria for evaluating student performance that are directly linked to course outcomes and student performance indicators. (1, 2)

- Occur regularly with attention to institutional context and programmatic need. (3, 6)

- Share assessment protocols with faculty teaching in the program and invite faculty to contribute to design and implementation. (4, 5, 6)

- Share assessment results with faculty to ensure assessment informs curriculum design and revisions. (1, 2)

- Recognize that assessment results influence and reflect accreditation of and financial resources available to programs. (6)

- Provide opportunities for assessors to discuss and come to an understanding of outcomes and scoring options. (4, 5)

- Faculty assessors should be compensated in ways that advantage them in their local contexts whether this involves financial compensation, reassigned time, or recognized service considered for annual review, promotion, and/or merit raises. (6)

- Contingent instructors are vital to programs and, ideally, their expertise should be considered in assessment processes. If, however, participation exceeds what is written into their contracts/labor expectations, appropriate compensation should be awarded. (6)

There is no perfect assessment measure, and best practices in all assessment contexts involve reflections by stakeholders on the effectiveness and ethics of all assessment practices. Assessments that involve timed tests, rely solely on machine scoring, or primarily judge writing based on prescriptive grammar and mechanics offer a very limited view of student writing ability and have a history of disproportionately penalizing students from marginalized populations. Ethical assessment practices provide opportunities to identify equity gaps in writing programs and classrooms and to use disaggregated data to make informed decisions about increasing educational opportunities for students.

Individual faculty and larger programs should carefully review their use of these assessment methods and critically weigh the benefits and ethics of these approaches. Additionally, when designing these assessment processes, programs should carefully consider the labor that will be required at all stages of the process to ensure an adequate base of faculty labor to maintain the program and to ensure that all faculty involved are appropriately compensated for that labor. Ethical assessment is always an ongoing process of negotiating the historical impacts of writing assessment, the need for a clear portrait of what is happening in classrooms and programs, and the concern for the best interests of all assessment participants.

Recommended Readings

Adler-Kassner, Linda, and Peggy O’Neill. Reframing Writing Assessment to Improve Teaching and Learning. Utah State UP, 2010.

Ball, Arnetha F. “Expanding the Dialogue on Culture as a Critical Component When Assessing Writing.” Assessing Writing, vol. 4, no. 2, 1997, pp. 169–202.

Broad, Bob. What We Really Value: Beyond Rubrics in Teaching and Assessing Writing . Utah State UP, 2003.

Cushman, Ellen. “Decolonizing Validity.” The Journal of Writing Assessment , vol. 9, no. 1, 2016, escholarship.org/uc/item/0xh7v6fb.

Elliot, Norbert. “A Theory of Ethics for Writing Assessment.” The Journal of Writing Assessment , vol. 9, no. 1, 2016, escholarship.org/uc/item/36t565mm.

Gomes, Mathew, et al . “ Enabling Meaningful Labor: Narratives of Participation in a Grading Contract. ” The Journal of Writing Assessment , vol. 13, no. 2, 2020, escholarship.org/uc/item/1p60j218.

Gomes, Mathew, and Wenjuan Ma. “ Engaging expectations: Measuring helpfulness as an alternative to student evaluations of teaching .” Assessing Writing , vol. 45, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2020.100464.

Green, David F., Jr. “Expanding the Dialogue on Writing Assessment at HBCUs: Foundational Assessment Concepts and Legacies of Historically Black Colleges and Universities.” College English , vol. 79, no. 2, 2016, pp. 152–173.

Grouling, Jennifer. “The Path to Competency-Based Certification: A Look at the LEAP Challenge and the VALUE Rubric for Written Communication.” The Journal of Writing Assessment , vol. 10, no. 1, 2017, escholarship.org/uc/item/5575w31k.

Hassel, Holly, and Joanne Giordano. “The Blurry Borders of College Writing: Remediation and the Assessment of Student Readiness.” College English , vol. 78, no. 1, 2015, pp. 56–80.

Helms, Janet E. “Fairness Is Not Validity or Cultural Bias in Racial-Group Assessment: A Quantitative Perspective.” American Psychologist , vol. 61, 2006, pp. 845–859, https://doi.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2F0003-066X.61.8.845.

Huot, Brian, and Peggy O’Neill. Assessing Writing: A Critical Sourcebook . Macmillan, 2009.

Inoue, Asao B. Antiracist Writing Assessment Ecologies: Teaching and Assessing Writing for a Socially Just Future . Parlor Press, 2015.

Inoue, Asao B., and Mya Poe, editors. Race and Writing Assessment. Peter Lang, 2012.

Johnson, David, and Lewis VanBrackle. “Linguistic Discrimination in Writing Assessment: How Raters React to African American ‘Errors’, ESL Errors, and Standard English Errors on a State-Mandated Writing Exam.” Assessing Writing, vol. 17, no. 1, 2012, pp. 35–54.

Johnson, Gavin P. “Considering the Possibilities of a Cultural Rhetorics Assessment Framework.” Pedagogy Blog, constellations: a cultural rhetorics publishing space , 26 August 2020, constell8cr.com/pedagogy-blog/considering-the-possibilities-of-a-cultural-rhetorics-assessment-framework/.

Lindsey, Peggy, and Deborah Crusan. “How Faculty Attitudes and Expectations toward Student Nationality Affect Writing Assessment.” Across the Disciplines: A Journal of Language, Learning, and Academic Writing , vol. 8, 2011, https://doi.org/10.37514/ATD-J.2011.8.4.23.

McNair, Tia Brown, et al. From Equity Talk to Equity Walk: Expanding Practitioner Knowledge for Racial Justice in Higher Education . Jossey-Bass, 2020.

Mislevy, Robert J. Sociocognitive Foundations of Educational Measurement . Routledge, 2018.

Newton, Paul E. “There Is More to Educational Measurement than Measuring: The Importance of Embracing Purpose Pluralism.” Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice , vol. 36, no. 2, 2017, pp. 5–15.

Perryman-Clark, Staci M. “Who We Are(n’t) Assessing: Racializing Language and Writing Assessment in Writing Program Administration.” College English, vol. 79, no. 2, 2016, pp. 206–211.

Poe, Mya, et al. “The Legal and the Local: Using Disparate Impact Analysis to Understand the Consequences of Writing Assessment.” College Composition and Communication , vol. 65, no. 4, 2014, pp. 588–611.

Poe, Mya, et al. Writing Assessment, Social Justice, and the Advancement of Opportunity . The WAC Clearinghouse; University Press of Colorado, 2018.

Poe, Mya, and John Aloysius Cogan Jr. “Civil Rights and Writing Assessment: Using the Disparate Impact Approach as a Fairness Methodology to Determine Social Impact.” Journal of Writing Assessment , vol. 9, no. 1, 2016, escholarship.org/uc/item/08f1c307.

Randall, Jennifer. “Color-Neutral Is Not a Thing: Redefining Construct Definition and Representation through a Justice-Oriented Critical Antiracist Lens.” Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice , 2021, https://doi.org/10.1111/emip.12429.

Rhodes, Terrel L., and Ashley Finley. Using the VALUE Rubrics for Improvement of Learning and Authentic Assessment. AAC&U, 2013.

Slomp, David. “Complexity, Consequence, and Frames: A Quarter Century of Research in Assessing Writing.” Assessing Writing , vol. 42, no. 4, 2019, pp. 1–17.

———. “Ethical Considerations and Writing Assessment.” Journal of Writing Assessment , vol. 9, no. 1, 2016, escholarship.org/uc/item/2k14r1zg.

———. “An Integrated Design and Appraisal Framework for Ethical Writing Assessment.” The Journal of Writing Assessment, vol. 9, no. 1, 2016, escholarship.org/uc/item/4bg9003k.

Solano-Flores, Guillermo. “Assessing the Cultural Validity of Assessment Practices: An Introduction.” Cultural Validity in Assessment: Addressing Linguistic and Cultural Diversity, edited by María del Rosario Basterra et al., Routledge, 2002, pp. 3–21.

Tan, Tony Xing, et al. “Linguistic, Cultural and Substantive Patterns in L2 Writing: A Qualitative Illustration of Mislevy’s Sociocognitive Perspective on Assessment.” Assessing Writing , vol. 51, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2021.100574.

Toth, Christie, and Laura Aull. “Directed Self-Placement Questionnaire Design: Practices, Problems, Possibilities.” Assessing Writing, vol. 20, 2014, pp. 1–18.

Toth, Christie, et al. “Introduction: Writing Assessment, Placement, and the Two-Year College.” Journal of Writing Assessment , vol. 12, no. 1, 2019. (Special Issue on Two-Year Colleges and Placement)

Acknowledgments

This statement was generously revised by the Task Force to Create CCCC Guidelines for College Writing Assessment: Inclusive, Sustainable, and Evidence-Based Practices. The members of this task force include:

Anna Hensley, Co-chair Joyce Inman, Co-chair Melvin Beavers Raquel Corona Bump Halbritter Leigh Jonaitis L iz Tinoco Rachel Wineinger

This position statement may be printed, copied, and disseminated without permission from NCTE.

- Renew Your Membership

- Become a Member

- Newcomers–learn more!

- Join the Online Conversations

- Read CCC Articles

- Find a Position Statement

- Learn about Committees

- Read Studies in Writing & Rhetoric Books

- Review Convention Programs

- Find a Resolution

- Browse Composition Books

- Learn about the 2024 Annual Convention

Copyright © 1998 - 2024 National Council of Teachers of English. All rights reserved in all media.

1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, Illinois 61801-1096 Phone: 217-328-3870 or 877-369-6283

Looking for information? Browse our FAQs , tour our sitemap and store sitemap , or contact NCTE

Read our Privacy Policy Statement and Links Policy . Use of this site signifies your agreement to the Terms of Use

http://www.ncte.org/cccc http://www.ncte.org/cccc

Organization User Resources

- Return to NCTE

Website Search

- Grants & Awards

- CCC Online Archive

- Studies in Writing and Rhetoric

- Bibliography of Composition and Rhetoric

- Conventions & Meetings

- Policies and Guidelines

- Resolutions

- Visit the University of Nebraska–Lincoln

- Apply to the University of Nebraska–Lincoln

- Give to the University of Nebraska–Lincoln

Search Form

Assessing student writing, what does it mean to assess writing.

- Suggestions for Assessing Writing

Means of Responding

Rubrics: tools for response and assessment, constructing a rubric.

Assessment is the gathering of information about student learning. It can be used for formative purposes−−to adjust instruction−−or summative purposes: to render a judgment about the quality of student work. It is a key instructional activity, and teachers engage in it every day in a variety of informal and formal ways.

Assessment of student writing is a process. Assessment of student writing and performance in the class should occur at many different stages throughout the course and could come in many different forms. At various points in the assessment process, teachers usually take on different roles such as motivator, collaborator, critic, evaluator, etc., (see Brooke Horvath for more on these roles) and give different types of response.

One of the major purposes of writing assessment is to provide feedback to students. We know that feedback is crucial to writing development. The 2004 Harvard Study of Writing concluded, "Feedback emerged as the hero and the anti-hero of our study−powerful enough to convince students that they could or couldn't do the work in a given field, to push them toward or away from selecting their majors, and contributed, more than any other single factor, to students' sense of academic belonging or alienation" (http://www.fas.harvard.edu/~expos/index.cgi?section=study).

Source: Horvath, Brooke K. "The Components of Written Response: A Practical Synthesis of Current Views." Rhetoric Review 2 (January 1985): 136−56. Rpt. in C Corbett, Edward P. J., Nancy Myers, and Gary Tate. The Writing Teacher's Sourcebook . 4th ed. New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 2000.

Suggestions for Assessing Student Writing

Be sure to know what you want students to be able to do and why. Good assessment practices start with a pedagogically sound assignment description and learning goals for the writing task at hand. The type of feedback given on any task should depend on the learning goals you have for students and the purpose of the assignment. Think early on about why you want students to complete a given writing project (see guide to writing strong assignments page). What do you want them to know? What do you want students to be able to do? Why? How will you know when they have reached these goals? What methods of assessment will allow you to see that students have accomplished these goals (portfolio assessment assigning multiple drafts, rubric, etc)? What will distinguish the strongest projects from the weakest?

Begin designing writing assignments with your learning goals and methods of assessment in mind.

Plan and implement activities that support students in meeting the learning goals. How will you support students in meeting these goals? What writing activities will you allow time for? How can you help students meet these learning goals?

Begin giving feedback early in the writing process. Give multiple types of feedback early in the writing process. For example, talking with students about ideas, write written responses on drafts, have students respond to their peers' drafts in process, etc. These are all ways for students to receive feedback while they are still in the process of revising.

Structure opportunities for feedback at various points in the writing process. Students should also have opportunities to receive feedback on their writing at various stages in the writing process. This does not mean that teachers need to respond to every draft of a writing project. Structuring time for peer response and group workshops can be a very effective way for students to receive feedback from other writers in the class and for them to begin to learn to revise and edit their own writing.

Be open with students about your expectations and the purposes of the assignments. Students respond better to writing projects when they understand why the project is important and what they can learn through the process of completing it. Be explicit about your goals for them as writers and why those goals are important to their learning. Additionally, talk with students about methods of assessment. Some teachers have students help collaboratively design rubrics for the grading of writing. Whatever methods of assessment you choose, be sure to let students in on how they will be evaluated.

Do not burden students with excessive feedback. Our instinct as teachers, especially when we are really interested in students´ writing is to offer as many comments and suggestions as we can. However, providing too much feedback can leave students feeling daunted and uncertain where to start in terms of revision. Try to choose one or two things to focus on when responding to a draft. Offer students concrete possibilities or strategies for revision.

Allow students to maintain control over their paper. Instead of acting as an editor, suggest options or open-ended alternatives the student can choose for their revision path. Help students learn to assess their own writing and the advice they get about it.

Purposes of Responding We provide different kinds of response at different moments. But we might also fall into a kind of "default" mode, working to get through the papers without making a conscious choice about how and why we want to respond to a given assignment. So it might be helpful to identify the two major kinds of response we provide:

- Formative Response: response that aims primarily to help students develop their writing. Might focus on confidence-building, on engaging the student in a conversation about her ideas or writing choices so as to help student to see herself as a successful and promising writer. Might focus on helping student develop a particular writing project, from one draft to next. Or, might suggest to student some general skills she could focus on developing over the course of a semester.

- Evaluative Response: response that focuses on evaluation of how well a student has done. Might be related to a grade. Might be used primarily on a final product or portfolio. Tends to emphasize whether or not student has met the criteria operative for specific assignment and to explain that judgment.

We respond to many kinds of writing and at different stages in the process, from reading responses, to exercises, to generation or brainstorming, to drafts, to source critiques, to final drafts. It is also helpful to think of the various forms that response can take.

- Conferencing: verbal, interactive response. This might happen in class or during scheduled sessions in offices. Conferencing can be more dynamic: we can ask students questions about their work, modeling a process of reflecting on and revising a piece of writing. Students can also ask us questions and receive immediate feedback. Conference is typically a formative response mechanism, but might also serve usefully to convey evaluative response.

- Written Comments on Drafts

- Local: when we focus on "local" moments in a piece of writing, we are calling attention to specifics in the paper. Perhaps certain patterns of grammar or moments where the essay takes a sudden, unexpected turn. We might also use local comments to emphasize a powerful turn of phrase, or a compelling and well-developed moment in a piece. Local commenting tends to happen in the margins, to call attention to specific moments in the piece by highlighting them and explaining their significance. We tend to use local commenting more often on drafts and when doing formative response.

- Global: when we focus more on the overall piece of writing and less on the specific moments in and of themselves. Global comments tend to come at the end of a piece, in narrative-form response. We might use these to step back and tell the writer what we learned overall, or to comment on a pieces' general organizational structure or focus. We tend to use these for evaluative response and often, deliberately or not, as a means of justifying the grade we assigned.

- Rubrics: charts or grids on which we identify the central requirements or goals of a specific project. Then, we evaluate whether or not, and how effectively, students met those criteria. These can be written with students as a means of helping them see and articulate the goals a given project.

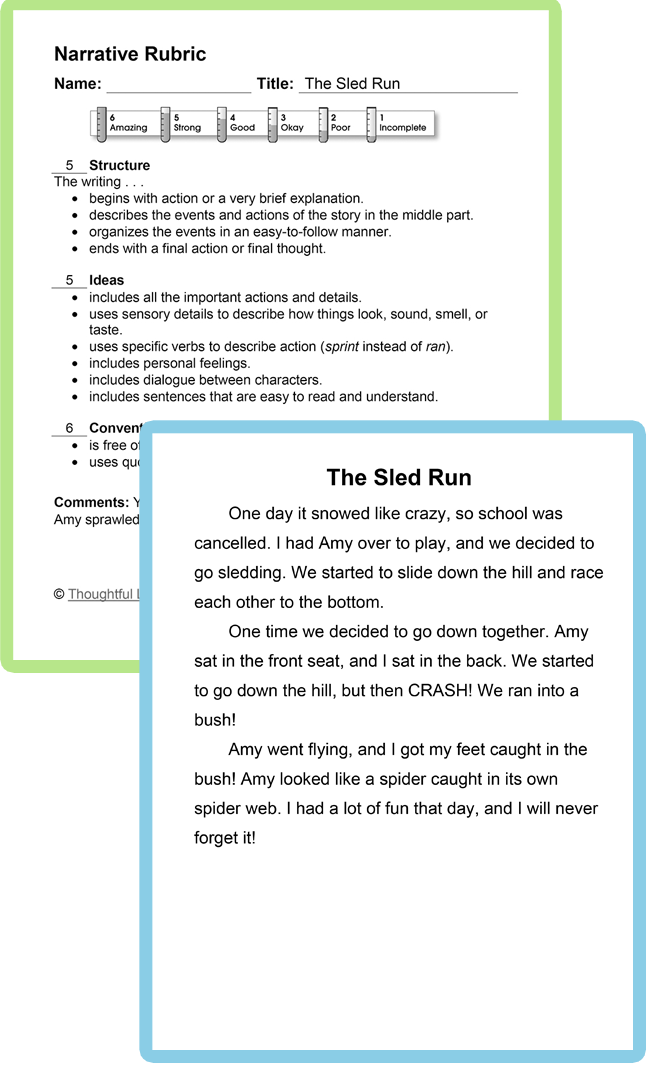

Rubrics are tools teachers and students use to evaluate and classify writing, whether individual pieces or portfolios. They identify and articulate what is being evaluated in the writing, and offer "descriptors" to classify writing into certain categories (1-5, for instance, or A-F). Narrative rubrics and chart rubrics are the two most common forms. Here is an example of each, using the same classification descriptors:

Example: Narrative Rubric for Inquiring into Family & Community History

An "A" project clearly and compellingly demonstrates how the public event influenced the family/community. It shows strong audience awareness, engaging readers throughout. The form and structure are appropriate for the purpose(s) and audience(s) of the piece. The final product is virtually error-free. The piece seamlessly weaves in several other voices, drawn from appropriate archival, secondary, and primary research. Drafts - at least two beyond the initial draft - show extensive, effective revision. Writer's notes and final learning letter demonstrate thoughtful reflection and growing awareness of writer's strengths and challenges.

A "B" project clearly and compellingly demonstrates how the public event influenced the family/community. It shows strong audience awareness, and usually engages readers. The form and structure are appropriate for the audience(s) and purpose(s) of the piece, though the organization may not be tight in a couple places. The final product includes a few errors, but these do no interfere with readers' comprehension. The piece effectively, if not always seamlessly, weaves several other voices, drawn from appropriate archival, secondary, and primary research. One area of research may not be as strong as the other two. Drafts - at least two beyond the initial drafts - show extensive, effective revision. Writer's notes and final learning letter demonstrate thoughtful reflection and growing awareness of writer's strengths and challenges.

A "C" project demonstrates how the public event influenced the family/community. It shows audience awareness, sometimes engaging readers. The form and structure are appropriate for the audience(s) and purpose(s), but the organization breaks down at times. The piece includes several, apparent errors, which at times compromises the clarity of the piece. The piece incorporates other voices, drawn from at least two kinds of research, but in a generally forced or awkward way. There is unevenness in the quality and appropriateness of the research. Drafts - at least one beyond the initial draft - show some evidence of revision. Writer's notes and final learning letter show some reflection and growth in awareness of writer's strengths and challenges.

A "D" project discusses a public event and a family/community, but the connections may not be clear. It shows little audience awareness. The form and structure is poorly chosen or poorly executed. The piece includes many errors, which regularly compromise the comprehensibility of the piece. There is an attempt to incorporate other voices, but this is done awkwardly or is drawn from incomplete or inappropriate research. There is little evidence of revision. Writer's notes and learning letter are missing or show little reflection or growth.

An "F" project is not responsive to the prompt. It shows little or no audience awareness. The purpose is unclear and the form and structure are poorly chosen and poorly executed. The piece includes many errors, compromising the clarity of the piece throughout. There is little or no evidence of research. There is little or no evidence of revision. Writer's notes and learning letter are missing or show no reflection or growth.

Chart Rubric for Community/Family History Inquiry Project

| Clearly and compellingly demonstrates influence of event | Clearly and compellingly demonstrates influence of event | Demonstrates influence of event | Discusses event; connections unclear | Not responsive to prompt | |

| Strong audience awareness; engages throughout | Strong audience awareness; usually engages | Audience awareness; sometimes engages | Little audience awareness | Little or no audience awareness | |

| Appropriate for audience(s), purpose(s) | Appropriate for audience(s), purpose(s); organization occasionally not tight | Appropriate for audience(s), purpose(s); organization breaks down at times | Poorly chosen or poorly executed | Poorly chosen and executed | |

| Virtually error-free | Few, unobtrusive errors | Several apparent, sometimes obtrusive errors | Many, obtrusive errors | Many obtrusive errors | |

| Seamlessly weaves voices; 3 kinds of research | Effectively weaves voices; 3 kinds of research; 1 may not be as strong | Incorporates other voices, but awkwardly; at least 2 kinds of research | Attempts to incorporate voices, but awkwardly; poor research | Little or no evidence of research | |

| Extensive, effective (at least 2 drafts beyond 1st) | Extensive, effective (at least 2 drafts beyond 1st) | Some evidence of revision | Little evidence or revision | No evidence of revision | |

| Thoughtful reflection; growing self-awareness | Thoughtful reflection; growing self-awareness | Some evidence of reflection, growth | Little evidence of reflection | Little or no evidence of reflection | |

| Thoughtful reflection; growing self-awareness | Thoughtful reflection; growing self-awareness | Some evidence of reflection, growth | Little evidence of reflection | Little or no evidence of reflection |

All good rubrics begin (and end) with solid criteria. We always start working on rubrics by generating a list - by ourselves or with students - of what we value for a particular project or portfolio. We generally list far more items than we could use in a single rubric. Then, we narrow this list down to the most important items - between 5 and 7, ideally. We do not usually rank these items in importance, but it is certainly possible to create a hierarchy of criteria on a rubric (usually by listing the most important criteria at the top of the chart or at the beginning of the narrative description).

Once we have our final list of criteria, we begin to imagine how writing would fit into a certain classification category (1-5, A-F, etc.). How would an "A" essay differ from a "B" essay in Organization? How would a "B" story differ from a "C" story in Character Development? The key here is to identify useful descriptors - drawing the line at appropriate places. Sometimes, these gradations will be precise: the difference between handing in 80% and 90% of weekly writing, for instance. Other times, they will be vague: the difference between "effective revisions" and "mostly effective revisions", for instance. While it is important to be as precise as possible, it is also important to remember that rubric writing (especially in writing classrooms) is more art than science, and will never - and nor should it - stand in for algorithms. When we find ourselves getting caught up in minute gradations, we tend to be overlegislating students´- writing and losing sight of the purpose of the exercise: to support students' development as writers. At the moment when rubric-writing thwarts rather than supports students' writing, we should discontinue the practice. Until then, many students will find rubrics helpful -- and sometimes even motivating.

Writing Assessment

Main navigation.

Effective writing pedagogy depends on assessment practices that set students up for success and are fair and consistent.

Ed White and Stanford Lecturer Cassie A. Wright have argued influentially that good assessment thus begins with assignment design, including a clear statement of learning objectives and comments on drafts (“response”); thus:

ASSESSMENT DESIGN + RESPONSE + EVALUATION = ASSESSMENT (White 1984; White and Wright 2015)

Assessment theory further supports the idea that good writing assessment is:

Local , responding directly to student writing itself and a specific, individual assignment

Rhetorically based , responding to the relationship between what a student writes, how they write and who they are writing for

Accessible , legibly written in language that a student can understand, and available in a time frame that allows them to take feedback into consideration for subsequent writing assignments

Theoretically consistent such that assignment expectations, teaching, and feedback are all aligned

(O’Neill, Moore, and Huot 57)

For these reasons, we must think about assessment holistically, in terms of how we articulate our evaluation criteria , give feedback to students, and invite them to respond to others’ and their own writing .

Works Cited

O’Neill, Peggy, Cindy Moore, and Brian Huot. A Guide to College Writing Assessment. Logan: Utah State UP, 2009. Print.

White, Edward M. Teaching and Assessing Writing. Proquest Info and Learning, 1985. Print.

White, Edward M., and Cassie A. Wright. Assigning, Responding, Evaluating: A Writing Teacher’s Guide. 5th ed. Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2015. Print.

A Guide to Standardized Writing Assessment

Overview of writing assessment, holistic scoring, evolving technology, applications in the classroom.

In the United States, policymakers, advisory groups, and educators increasingly view writing as one of the best ways to foster critical thinking and learning across the curriculum. The nonprofit organization Achieve worked with five states to define essential English skills for high school graduates and concluded thatStrong writing skills have become an increasingly important commodity in the 21st century. . . . The discipline and skill required to create, reshape, and polish pieces of writing “on demand” prepares students for the real world, where they inevitably must be able to write quickly and clearly, whether in the workplace or in college classrooms. (2004, p. 26)

My daughters are not alone. Increasingly, students are being asked to write for tests that range from NCLB-mandated subject assessments in elementary school to the new College Board SAT, which will feature a writing section beginning in March 2005. Educators on the whole have encouraged this development. As one study argues,Since educators can use writing to stimulate students' higher-order thinking skills—such as the ability to make logical connections, to compare and contrast solutions to problems, and to adequately support arguments and conclusions—authentic assessment seems to offer excellent criteria for teaching and evaluating writing. (Chapman, 1990)

Achieve, Inc. (2004). Do graduation tests measure up? A closer look at state high school exit exams . Washington, DC: Author.

Boomer, G. (1985). The assessment of writing. In P. J. Evans (Ed.), Directions and misdirections in English evaluation (pp. 63–64). Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Council of Teachers of English.

Chapman, C. (1990). Authentic writing assessment . Washington, DC: American Institutes for Research. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 328 606)

Cooper, C. R., & Odell, L. (1977). Evaluating writing: Describing, measuring, judging . Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Duke, C. R., & Sanchez, R. (1994). Giving students control over writing assessment. English Journal, 83 (4), 47–53.

Fiderer, A. (1998). Rubrics and checklists to assess reading and writing: Time-saving reproducible forms for meaningful literacy assessment . Bergenfield, NJ: Scholastic.

Murphy, S., & Ruth, L. (1999). The field-testing of writing prompts reconsidered. In M. M. Williamson & B. A. Huot (Eds.), Validating holistic scoring for writing assessment: Theoretical and empirical foundations (pp. 266–302). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Ruth, L., & Murphy, S. (1988). Designing tasks for the assessment of writing . Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Skillings, M. J., & Ferrell, R. (2000). Student-generated rubrics: Bringing students into the assessment process. Reading Teacher, 53 (6), 452–455.

White, J. O. (1982). Students learn by doing holistic scoring. English Journal , 50–51.

• 1 For information on individual state assessments and rubrics, visit http://wdcrobcolp01.ed.gov/Programs/EROD/org_list.cfm?category_ID=SEA and follow the links to the state departments of education.

ASCD is a community dedicated to educators' professional growth and well-being.

Let us help you put your vision into action., from our issue.

- Student Voice

- Strategic Priorities

- Workshops & Training

- Case Studies

- Assessment Principles

- Writing an Effective Assessment Brief

- Writing Assessment Criteria and Rubrics

- Formative Assessment

- Options for Peer Assessment and Peer Review

- Programme Focussed Assessment

- What Makes Good Feedback

- Feedback on Exams

- Presentations and Video Assessment

- Digital Assessment: Canvas and Turnitin

- Take Home Exams

- Choosing a Digital Assessment Tool

- Design Thinking

- Synchronous Online Teaching

- Scheduling Synchronous Sessions

- Recording Online Teaching

- Zoom or Teams?

- Digital Accessibility

- Universal Design for Learning

- Artificial Intelligence (AI)

- 'In-session' Social Activities

- Facilitated Social Engagement

- Student-led Spaces

- Reflective Practice

- Learning Analytics

- Recording Videos

- Editing Videos

- Sharing Videos

- Audio and Podcasts

- Captions and Transcripts

- Hybrid Teaching

- Large Group Teaching

- Laboratory Teaching

- Field Trips and Virtual Fieldwork

- Peer Dialogue

- Digital Polling

- Copyright and IPR

- Principal Fellowship of HEA

- National Teaching Fellowship Scheme

- Internal Support

- External Resources

- Collaborative Award for Teaching Excellence

- Newcastle Educational Practice Scheme (NEPS)

- Introduction to Learning and Teaching (ILTHE)

- UKPSF Experiential Route

- Evidencing Learning and Teaching Skills (ELTS)

- Learning and Teaching Conference

- Education Enhancement Fund

- Vice-Chancellor's Education Excellence Awards

- Peer Mentoring

- Personal Tutoring

- Virtual Exchange

- Information and Digital Literacy

- Academic and Study Skills

- Special Collections and Archives

- Reading List Toolkit

- Employability and Graduate Skills

- Academic Skills Kit

- Numeracy, Maths and Stats

- New Courses (24-25)

- Access Canvas

- Canvas Baseline

- Community Information

- Help and Support

- Canvas Quizzes

- Canvas New Analytics

- Ally for Canvas

- Third Party Tool Integrations

- Roles, Permissions and Access

- Recording on Campus

- Recording at Home

- Edit & Share Recordings

- Captions in ReCap

- ReCap Live Broadcast

- ReCap Enabled Venues

- Events & Conferences

- ReCap Booking Requests

- Multiple Bookings

- ReCap Update Information

- PCap Updates

- Create and manage reflections

- Identify the skills you are developing

- Communicate and collaborate

- NU Reflect tools

- Personal Tutoring & Support landing page

- Data Explorer

- Open Badges

- Supported Software

NEW: A vision for education and skills at Newcastle University: Education for Life 2030+

- Newcastle University

- Learning and Teaching @ Newcastle

- Effective Practice

- Assessment and Feedback

Assessment Criteria and Assessment Rubrics

Assessment rubrics and assessment criteria are both tools used for establishing a clear understanding between staff and students about what is expected from assessed work, and how student knowledge is evaluated. Assessment rubrics and assessment criteria are often referred to interchangeably but it's important to understand they have slightly different purposes.

Assessment criteria are specific standards or guidelines that outline what is expected of a student in a particular assessment task. They are often used to set clear guidelines for what constitutes success in each assessment task but are generally not broken down into discrete levels of performance. They can, however, provide the foundations for creating assessment rubrics.

An assessment rubric is a more detailed and structured tool that breaks down the assessment criteria into different levels or categories of performance, typically ranging from poor to excellent, on a percentage scale. They can make a markers life easier by ensuring consistency and objectivity in grading or evaluation, provide a clear framework for assessing performance, and reduce time spent on grading.

Additionally, assessment rubrics can help students to understand the aims and requirements of an assessment task and can support them in understanding the outcome of their assessed work i.e., how the markers reached their decision, positive areas of feedback and feedforward comments that allow students to recognise their future development needs.

Top Tips for Writing Assessment Rubrics

- Start by clarifying the purpose of the assessment and what specific skills or learning outcomes you want to evaluate. This will guide the development of your rubric.

- Break down the assessment into its essential components or criteria . These should reflect the specific skills or knowledge you want to assess. Be clear and specific about what you're looking for.

- Use straightforward and unambiguous language in your rubric. Avoid jargon or complex terminology that may confuse students or other assessors.

- Create a clear and logical progression of performance levels, each criterion should provide detailed descriptions of what constitutes achievement at that level (check if your school has example assessment rubrics/criteria as a starting point).

- Consider assigning different weightings to each criterion. Some of the rubric criterion will be more significant than others , g., theoretical application, criticality, and structure weightings will defer (this will be guided by the knowledge outcomes).

- Check for parity across grade boundaries Consider what a student would need to do to obtain each classification- be clear about the components which make up good performance, e.g., clear structure, argument, engagement with critical material. It is best to start at a pass, and work towards a first class. Criteria should concentrate on what the student has done, rather than what they have not done.

- Leave space on the rubric for assessors to provide feedback to students . This can be particularly helpful for offering constructive feedback on areas of improvement.

- Best practice is to ask colleagues to read your criteria and check them for clarity before using them.

- Criteria may be revised from year-to-year in response to feedback and your own experience of using it Rubrics can and should evolve to become more effective over time.

Example: UG Stage 1 Rubric

Example: PGT Rubric

Case Studies Database

There are lots of examples of how formative assessment is used here at Newcastle on our Case Studies Database.

Get in touch

In order to continue enjoying our site, we ask that you confirm your identity as a human. Thank you very much for your cooperation.

Theory-Based Approach to Academic Writing Assessment in Higher Education: A Conceptual Framework for Assessment Design and Development

- First Online: 25 May 2022

Cite this chapter

- Cecilia Guanfang Zhao 3

627 Accesses

2 Citations

An examination of the current writing assessment practices indicates that unlike measurement theory, “writing theory has had a minimal influence on writing assessment” (Behizadeh and Engelhard, Assess Writ 16(3):189–211, 2011: 189). Despite the widely accepted theoretical conception of writing as a cognitive process and social practice situated in a particular socio-cultural context, the most often employed writing assessment task is still prompt-based impromptu essay writing, especially in large-scale English as a Foreign Language (EFL) assessment contexts. However, assessment specialists have long called into question the usefulness of impromptu essay writing in response to a single prompt. As a response to the above observation of the lack of theoretical support and generalizability of results in our current writing assessment practices, this chapter seeks to propose and outline an alternative writing assessment design informed by and reflecting more faithfully theoretical conceptions of writing and language ability. The chapter starts with a brief review of the existing writing theories and a survey of the current practices of writing assessment on large-scale high-stakes EFL tests, with a particular focus on those within the Chinese context. By juxtaposing theoretical conceptions of the construct and the actual operationalization of this construct on these EFL tests, the chapter highlights several salient issues and argues for an alternative approach to writing assessment, especially for academic purposes in higher education. A conceptual framework for such an assessment is presented to illustrate how writing theories can be used to inform and guide test design and development. The chapter ends with a discussion of the value and practical implications of such assessment design in various educational or assessment settings, together with potential challenges for the developers and users of this alternative assessment approach.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or Ebook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Enhancing English writing competence in higher education: a comparative study of teacher-only assessment versus teacher and student self-assessment approaches

Designing and Rating Academic Writing Tests: Implications for Test Specifications

Differential impacts of e-portfolio assessment on language learners’ engagement modes and genre-based writing improvement

Bachman, L. F. (1990). Fundamental considerations in language testing . Oxford University Press.

Google Scholar

Bachman, L. F., & Palmer, A. (1996). Language testing in practice: Designing and developing useful language tests . Oxford University Press.

Bachman, L. F., & Palmer, A. S. (2010). Language assessment in practice: Developing language assessments and justifying their use in the real world . Oxford University Press.

Banerjee, J., Yan, X., Chapman, M., & Elliot, H. (2015). Keeping up with the times: Revising and refreshing a rating scale. Assessing Writing, 26 , 5–19.

Article Google Scholar

Bawarshi, A. S., & Reiff, M. J. (2010). Genre: An introduction to history, theory, research, and pedagogy . Parlor Press.

Bazerman, C. (2015). What do social cultural studies of writing tell us about learning to write? In C. A. MacArthur, S. Graham, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Handbook of writing research (2nd ed., pp. 11–22). Guilford Press.

Beach, R., Newell, G. E., & VanDerHeide, J. (2015). A sociocultural perspective on writing development: Toward an agenda for classroom research on students’ use of social practices. In C. A. MacArthur, S. Graham, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Handbook of writing research (2nd ed., pp. 11–22). Guilford Press.

Beck, S. W., Llosa, L., Black, K., & Trzeszkowski-Giese, A. (2015). Beyond the rubric: Think-alouds as a diagnostic assessment tool for high school writing Teachers. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 58 (8), 670–681.

Behizadeh, N., & Engelhard, G. (2011). Historical view of the influences of measurement and writing theories on the practice of writing assessment in the United States. Assessing Writing, 16 (3), 189–211.

Bereiter, C., & Scardamalia, M. (1987). The psychology of written composition . Erlbaum.

Bloome, D., Carvalho, G. T., & Rue, S. (2018). Researching academic literacies. In A. Phakiti, P. D. Costa, P. Plonsky, & S. Starfield (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of applied linguistics research methodology (1st ed., pp. 887–902). Palgrave Macmillan.

Chapter Google Scholar

Britton, J., Burgess, T., Martin, N., McLeod, A., & Rosen, H. (1975). The development of writing abilities (11–18) . Macmillan.

Cai, J. (2002). The impact of CET-4 and CET-6 writing requirements and rubrics on Chinese students’ writing. Journal of PLA University of Foreign Languages, 25 (5), 49–53.

Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1980). Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Applied Linguistics, 1 (1), 1–47.

Chan, S., Inoue, C., & Taylor, L. (2015). Developing rubrics to assess the reading-into-writing skills: A case study. Assessing Writing, 26 , 20–37.

Chen, W. (2017). On NMET writing tasks and their future development. China Examinations, 302 , 44–47.

Cho, Y. (2003). Assessing writing: Are we bound by only one method? Assessing Writing, 8 (3), 165–191.

Crusan, D. (2014). Assessing writing. In A. J. Kunnan (Ed.), The companion to language assessment (pp. 1–15). Wiley Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118411360.wbcla067

Cumming, A. (1998). Theoretical perspectives on writing. Annual review of applied linguistics, 18 , 61–78.

Deane, P., Odendahl, N., Quinlan, T., Fowles, M., Welsh, C., & Bivens-Tatum, J. (2008). Cognitive models of writing: Writing proficiency as a complex integrated skill (ETS RR-08-55). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2333-8504.2008.tb02141.x

Deng, J. (Ed.). (2017). Guide to test for English Majors, Band Eight . Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press.

Dong, M., Gao, X., & Yang, Z. (2011). A longitudinal study of writing tasks on the NMET national test papers (1989-2011). Educational Measurement and Evaluation, 10 , 47–52.

Flower, L., & Hayes, J. R. (1981). A cognitive process theory of writing. College Composition and Communication, 32 (4), 365–387.

Gu, X., & Yang, Z. (2009). A study of the CET writing test items over the past two decades. Foreign Languages and Their Teaching, 243 , 21–26.

Hamp-Lyons, L. (2001). Fourth generation writing. In T. Silva & P. K. Matsuda (Eds.), On second language writing (pp. 117–129). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Hamp-Lyons, L. (2016a). Farewell to holistic scoring? Assessing Writing, 27 , A1–A2.

Hamp-Lyons, L. (2016b). Farewell to holistic scoring. Part Two: Why build a house with only one brick? Assessing Writing, 29 , A1–A5.

Hamp-Lyons, L. (2016c). Unanswered questions for assessing writing in the HE. What should be assessed and how? Paper presented at the UKALTA Language Testing Forum (LTF 2016).

Hamp-Lyons, L., & Kroll, B. (1997). TOEFL 2000 – Writing: Composition, community, and assessment (TOEFL monograph series report no. 5). Educational Testing Service.

Hatfield, W. W. (1935). An experience curriculum in English: A report of a commission of the National Council of Teachers of English . D. Appleton-Century Company, Incorporated. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/experiencecurric00nati (Original work published 1935).

Hayes, J. R. (1996). A new framework for understanding cognition and affect in writing. In C. M. Levy & S. Ransdell (Eds.), The science of writing: Theories, methods, individual differences, and applications (pp. 1–27). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Hayes, J. R., & Flower, L. S. (1980). Identifying the organization of writing processes. In L. Gregg & E. Steinberg (Eds.), Cognitive process in writing: An interdisciplinary approach (pp. 3–30). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Hildyard, A. (1992). Written composition. In M. C. Alkin (Ed.), Encyclopedia of educational research (pp. 1528–1540). Macmillan Publishing Company.

Horowitz, D. M. (1986). What professors actually require: Academic tasks for the ESL classroom. TESOL Quarterly, 20 (3), 445–462.

Hyland, K. (2003). Genre-based pedagogies: A social response to process. Journal of Second Language Writing, 12 (1), 17–29.

Hyon, S. (1996). Genre in three traditions: Implications for ESL. TESOL Quarterly, 30 (4), 693–722.

Jin, Y., & Fan, J. (2011). Test for English majors (TEM) in China. Language Testing, 28 (4), 589–596.

Johns, A. M. (1991). English for specific purposes: Its history and contributions. In M. Celce-Murcia (Ed.), Teaching English as a second or foreign language (pp. 67–77). Heinle & Heinel.

Johns, A. M. (2008). Genre awareness for the novice academic student: An ongoing quest. Language Teaching, 41 (2), 237–252.

Johns, A. M. (2011). The future of genre in L2 writing: Fundamental, but contested, instructional decisions. Journal of Second Language Writing, 20 (1), 56–68.

Knoch, U. (2009). Diagnostic assessment of writing: A comparison of two rating scales. Language Testing, 26 (2), 275–304.

Lee, M. R., & Street, B. V. (1998). Student writing in higher education: An academic literacies approach. Studies in Higher Education, 23 (2), 157–172.

Lee, M. R., & Street, B. V. (2006). The “academic literacies” model: Theory and applications. Theory into Practice, 45 (4), 368–377.

Lu, Z. (2010). Possible path of reforming English tests for College Entrance Examination based on application ability. Educational Measurement and Evaluation, 1 , 15–26.

Moore, T., & Morton, J. (2005). Dimensions of difference: A comparison of university writing and IELTS writing. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 4 , 43–66.

National College English Testing Committee. (2016). Guide to College English Test (2016 revised version) . Retrieved from http://cet.neea.edu.cn/res/Home/1704/55b02330ac17274664f06d9d3db8249d.pdf

National Education Examinations Authority. (2018). Guide to Unified National Graduate Entrance Examination-English I & II (for non-English major) . Higher Education Press.

National Education Examinations Authority. (2019). Guide to National Matriculation English Test . Retrieved from http://www.neea.edu.cn/res/Home/1901/d15ec0514666ac280810099f9595b557.pdf

Pan, M. (Ed.). (2016). Guide to test for English Majors, Band Four . Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press.

Rohman, D. G. (1965). Pre-writing: The stage of discovery in the writing process. College Composition and Communication, 16 (2), 106–112.

Scardamalia, M., & Bereiter, C. (1991). Literate expertise. In K. A. Ericsson & J. Smith (Eds.), Toward a general theory of expertise: Prospects and limits (pp. 172–194). Cambridge University Press.

Snow, C. E., & Uccelli, P. (2009). The challenge of academic language. In D. R. Olson & N. Torrance (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of literacy (pp. 112–133). Cambridge University Press.

Spack, R. (1988). Initiating ESL students into the academic discourse community: How far should we go? TESOL Quarterly, 22 (1), 29–51.

Swales, J. (1990). Genre analysis: English in academic and research settings . Cambridge University Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Macau, Taipa, Macau, China

Cecilia Guanfang Zhao

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Cecilia Guanfang Zhao .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

University of Bedfordshire, Luton, Bedfordshire, UK

Liz Hamp-Lyons

Haoran Hi-Tech Building, Room 2203, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Zhao, C.G. (2022). Theory-Based Approach to Academic Writing Assessment in Higher Education: A Conceptual Framework for Assessment Design and Development. In: Hamp-Lyons, L., Jin, Y. (eds) Assessing the English Language Writing of Chinese Learners of English. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-92762-2_9

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-92762-2_9

Published : 25 May 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-92761-5

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-92762-2

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Frequently Asked Questions - Berkeley Writing Assessment: General Questions

Berkeley writing assessment: general questions, what is the berkeley writing assessment.

The Berkeley Writing Assessment is a 2-hour timed reading and writing activity done online. It is made up of a reading passage and questions that you will write an essay in response to, without the assistance of outside readings, books, websites, ChatGPT, or other people. You will also complete a survey that tells us about your experience with writing and writing classes.

Who should take the Berkeley Writing Assessment?

If you do not have a qualifying exam score at this time, or a C or higher in an English Composition course completed before starting Berkeley, you should consider taking the next available assessment.

The advantage of taking the upcoming assessment is to guarantee you will have the results in time for fall semester enrollment in mid-July to best determine if you will take COLWRIT R1A or qualify for enrollment in a Reading and Composition course that satisfies Part A. The Assessment is not required for enrollment in COLWRIT R1A, you can always enroll directly into the course. COLWRIT R1A completed with a letter grade of C or higher satisfies both Entry Level Writing and Reading and Composition Part A.

How do I sign up for the Assessment?

If you are a newly admitted first-year student who has accepted the offer to attend Berkeley, you will be assigned a Task in your CalCentral Dashboard to complete an Entry Level Writing Evaluation form. If you are a continuing Berkeley student, there is a registration link on this page.

You may take the Berkeley Writing Assessment only once.

How is the Assessment scored?

Each student essay will be read by two raters, working independently, to assign it a score from 1-6. The two scores are combined for the final score.

How do I pass the Assessment?

This is not an exam in the traditional sense. The Assessment doesn't have passing or failing grades. Instead, it will tell you which composition class is best for you given your skills and experience. If you receive a combined final score of 8 or higher, you will be recommended to take a 4-unit Reading and Composition Part A course in the department of your choice, including College Writing Programs. If your score is lower than 8, you will take College Writing (COLWRIT) R1A , a 6-unit course which satisfies both the Entry Level Writing and Reading and Composition Part A requirement.

How much does the Berkeley Writing Assessment cost?

There is a $196 fee for taking this assessment which is charged after you finish the assessment to your dashboard. You can view the charge in the Cal Central dashboard under the "My Finances" tab. Fee waivers for the Berkeley Writing Assessment are only granted to students who have qualified for the UC Application fee waiver. The Berkeley Writing Assessment fee waiver will be automatically processed if you already qualified for the UC Application fee waiver.

Can the fee for the Berkeley Writing Assessment be waived?

Fee waivers for the Berkeley Writing Assessment are only granted to students who qualified for the UC Application fee waiver. The Berkeley Writing Assessment fee waiver will be automatically processed if you have already qualified for the UC Application fee waiver.

I have a conflict with the most recent Assessment. Are there any make-up times?

Yes, the Berkeley Writing Assessment will be offered two times each year: the May administration (primarily for incoming students) and once during the fall semester. Note that you may take the Assessment only once . If you do not receive a qualifying score the first time you take the Assessment, and you have no other qualifying scores or acceptable transfer course completed prior to stating Berkeley, you should enroll in COLWRIT R1A

Do I need to take the Assessment in order to enroll in COLWRIT R1A?

No, you may enroll directly in COLWRIT R1A without an assessment score. Many students appreciate taking the course as a way to improve their reading and writing skills in a small class environment (College Writing classes have only 14 students per section). The class is designed to set you up for success with your future writing assignments at Berkeley.

I took the BWA. How long will it be until I get my score?

It generally takes around 3 weeks for your essay to be scored and for the score to be submitted before it appears in your records. You can find your BWA scores on your Cal Central dashboard under the "My Academics" tab.

How do I know which test scores satisfy ELWR?

A list of accepted tests and scores is found on the University of California Entry Level Writing Requirement page.

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- A–Z Index

- Operating Status

Assessment Methods

Questions and answers, can you provide some general guidance on writing assessments.

General policy guidance on assessment tools is provided in Chapter 2 of the Delegated Examining Operations Handbook (DEOH) , http://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/hiring-authorities/competitive-hiring/deo_handbook.pdf . Writing evaluations belong to a class of assessments referred to as "work sample tests." The guidance in the DEOH is not specific to writing assessments but the same principles would apply. As with any other procedure used to make an employment decision, a writing assessment should be:

- Supported by a job analysis,

- Linked to one or more critical job competencies,

- Included in the vacancy announcement, and

- Based on standardized reviewing and scoring procedures.

Other considerations may be important, such as the proposed method of use (e.g., as a selective placement factor, quality ranking factor) and specific measurement technique.

Writing performance has been evaluated using a wide range of techniques such as portfolio assessment, timed essay assignments, multiple-choice tests of language proficiency, self-reports of writing accomplishments (e.g., winning an essay contest, getting published), and grades in English writing courses. Each technique has its advantages and disadvantages.

For example, with the portfolio technique, applicants are asked to provide writing samples from school or work. The advantage of this technique is that it has high face validity (that is, applicants perceive that the measure is valid based on simple visual inspection). Disadvantages include difficulty verifying authorship, lack of opportunity (e.g., prior jobs may not have required report writing, the writing samples are proprietary or sensitive), and positive bias (e.g., only the very best writing pieces are submitted and others are selectively excluded).

Timed essay tests are also widely used to assess writing ability. The advantage of timed essay tests is that all applicants are assessed under standardized conditions (e.g., same topic, same time constraints). The disadvantage is that writing skill is based on a single work sample. Many experts believe truly realistic evaluations of writing skill require several samples of writing without severe time constraints and the use of multiple judges to enhance scoring reliability.

Multiple-choice tests of language proficiency have also been successfully employed to predict writing performance (perhaps because they assess the knowledge of grammar and language mechanics thought to underlie writing performance). Multiple-choice tests are relatively cheap to administer and score, but unlike the portfolio or essay techniques, they lack a certain amount of face validity. Research shows that the very best predictions of writing performance are obtained when essay and multiple choice tests are used in combination.

There is also an emerging field based on the use of automated essay scoring (AES) in assessing writing ability. Several software companies have developed different computer programs to rate essays by considering both the mechanics and content of the writing.

The typical AES program needs to be "trained" on what features of the text to extract. This is done by having expert human raters score 200 or more essays written on the same prompt (or question) and entering the results into the program. The program then looks for these relevant text features in new essays on the same prompt and predicts the scores that expert human raters would generate. AES offers several advantages over human raters such as immediate online scoring, greater objectivity, and capacity to handle high-volume testing. The major limitation of current AES systems is that they can only be applied to pre-determined and pre-tested writing prompts, which can be expensive and resource-intensive to develop.

However, please keep in mind that scoring writing samples can be very time-consuming regardless of method (e.g., whether the samples are obtained using the portfolio or by a timed essay). A scoring rubric (that is, a set of standards or rules for scoring) is needed to guide judges in applying the criteria used to evaluate the writing samples. Scoring criteria typically cover different aspects of writing such as content organization, grammar, sentence structure, and fluency. We would recommend that only individuals with the appropriate background and expertise be involved in the review, analysis, evaluation, and scoring of the writing samples.

Jump to navigation

- Inside Writing

- Teacher's Guides

- Student Models

- Writing Topics

- Minilessons

- Shopping Cart

- Inside Grammar

- Grammar Adventures

- CCSS Correlations

- Infographics

Sign up or login to use the bookmarking feature.

Writing Assessment for Teachers

“Students are more engaged when indicators of success are clearly spelled out.” —Judith Zorfass & Harriet Copel

Effective writing assessment begins with clear expectations. Share with your students the qualities of effective writing —structure, ideas, and conventions. Using the qualities is easy. Just assess writing with one of these qualities-based assessment tools: a teacher rating sheet , a general writing rubric , or a mode-specific rubric for narrative , explanatory , persuasive , literature response , or research writing.

Also check out these other assessment supports:

- Writing Assessment for Students

- The Qualities of Effective Writing