Join Discovery, the new community for book lovers

Trust book recommendations from real people, not robots 🤓

Blog – Posted on Wednesday, Sep 14

40 haiku poem examples everyone should know about.

Haiku is a form of traditional Japanese poetry, renowned for its simple yet hard-hitting style. They often take inspiration from nature and capture brief moments in time via effective imagery. Here are 40 Haiku poems that ought to leave you in wonder.

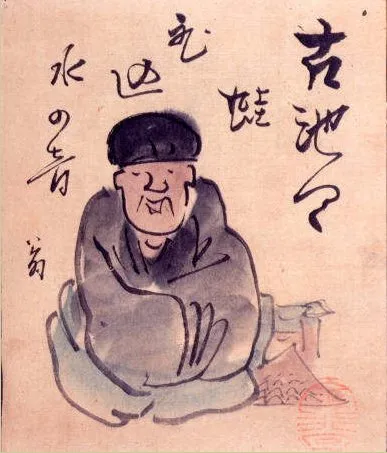

1. “The Old Pond” by Matsuo Bash ō

One of the four great masters of Japanese haiku, Matsuo Bashō is known for his simplistic yet thought-provoking haikus. “The Old Pond”, arguably his most famous piece, stays true to his style of couching observations of human nature within natural imagery. One interpretation is that by metaphorically using the ‘pond’ to symbolize the mind, Bashō brings to light the impact of external stimuli (embodied by the frog, a traditional subject of Japanese poetry) on the human mind.

2. “The light of a candle” by Yosa Buson

The light of a candle

Is transferred to another candle —

spring twilight.

Another of haiku’s Great Masters, Yosa Buson is known for bringing in a certain sensuality to his poems (perhaps owing to his training as a painter). In this haiku, his image of a single lit candle against the twilight artfully depicts how one candle can light another without being diminished — until you have a star-filled sky.

3. “Haiku Ambulance” by Richard Brautigan

A piece of green pepper

off the wooden salad bowl:

For an example of a haiku that doesn’t adhere to traditional conventions, look no further than Richard Brautigan’s cheeky “Haiku Ambulance”. Eagle-eyed readers will notice that the syllable count doesn’t fall into the 5-7-5 pattern, and the lines are off-balance, too. So what? Appropriately, this poem suggests that nothing means anything at all — in a pepper’s exile from a salad bowl, in the rules of a poem, or even (dare we say) life.

4. “A World of Dew” by Kobayashi Issa

This world of dew

is a world of dew,

and yet, and yet.

The third master of Japanese haiku, Kobayashi Issa, grew up in poverty. From this humble background emerged beautiful poetry that expressed empathy for the less fortunate, capturing daily hardships faced by common people. This particularly emotionally stirring haiku was written a month after the passing of Issa’s daughter.

5. “A Poppy Blooms” by Katsushika Hokusai

I write, erase, rewrite

Erase again, and then

A poppy blooms.

In this piece, Katsushika Hokusai draws similarities between life and his writing — both processes of repetitive creation and destruction. Neither are linear or smooth, and both demand constant work and perseverance. However, the reward of his perseverance is something undeniably beautiful.

6. “In the moonlight” by Yosa Buson

In pale moonlight

the wisteria’s scent

comes from far away.

Buson invites the reader to share in his nostalgia with elements from nature such as ‘pale moonlight’ and the ‘wisteria’s scent’ triggering the our visual and olfactory senses — the fact that the scent is coming from far away adds a transportive element to the poem, asking us to imagine the unseen beauty of this tree.

7. “The earth shakes” by Steve Sanfield

The earth shakes

just enough

to remind us.

Penned in English, poet Steve Sanfield’s only haiku is a quiet reminder of our mortality, inviting us to consider what may be important to us before it’s too late.

8. “In a Station of the Metro” by Ezra Pound

The apparition of these faces

in the crowd;

Petals on a wet, black bough.

All imagery with zero verbs, Ezra Pound delicately captures a still moment in time. The first image entirely comprises humans (faces in the crowd), while the second only shows nature (petals). By likening the two, the poet highlights the fleeting nature of life — be it the people we encounter every day or the wilting petals.

9. “The Taste of Rain” by Jack Kerouac

— Why kneel?

Yep, the iconoclastic author behind On the Road also wrote haikus! As one of the Beat Generation’s leading figures, he was part of a movement that produced some of the 20th century’s influential poems. This particular haiku has many interpretations — with many assuming this to be Kerouac’s take on religion and God.

10. “Haiku [for you]” by Sonia Sanchez

love between us is

speech and breath. loving you is

a long river running.

“Haiku [for you]” acts as a warm, comforting hug. The poet draws similarities between the nature of their love and that of ‘speech’ and ‘breath’ — natural and unforced. If someone whispered this to you, wouldn’t you feel love, too?

11. “Lines on a Skull” by Ravi Shankar

life’s little, our heads

sad. Redeemed and wasting clay

this chance. Be of use.

While many haiku have focused on the brevity of life, this entry from Ravi Shankar (no relation to the sitar player) takes a slightly darker approach. Using clay as a metaphor, Shankar reminds us that we have this one chance to shape our life — to either waste it away or be of use.

12. “O snail” by Kobayashi Issa

Climb Mount Fuji,

But slowly, slowly!

Aside from his pessimistic worldview, Issa was also renowned for shining a spotlight on smaller, less-than-glamorous creatures like grasshoppers, bugs, and sparrows. In “O snail”, he gently reminds the determined snail that while there are important things to do in life (like climbing mountains), there’s more to life than speed! The mountain isn’t going to go anywhere, is it?

13. “I want to sleep” by Masaoka Shiki

I want to sleep

Swat the flies

Softly, please.

The last of the Four Great Masters of haiku, Masaoka Shiki had a very direct writing style. Suffering tuberculosis for much of his life, his poetry was an outlet for his isolation. He would often focus on the trivial details of sick-room life, and in this haiku, his sadness and fatigue are almost palpable.

14. “JANUARY” by Paul Holmes

Delightful display

Snowdrops bow their pure white heads

To the sun's glory.

This haiku is a part of Paul Holmes’ A Year in Haiku Poem, where he attempts to capture the essence of each month of the year. Holmes does so fittingly, using vivid imagery to depict the seamless changing of the seasons— as the snowdrops bow their ‘white heads’ to make way for the sun’s glory.

15. “[snowmelt— ]” by Penny Harter

on the banks of the torrent

small flowers

By placing the river’s powerful torrent next to a delicate flower, Harter captures how all of nature’s diverse elements coexist beautifully. While the torrent certainly paints a more aggressive image than most haiku, it's balanced by the idea of the snow melting and the delicacy of the flowers emerging from spring.

16. [meteor shower] by Michael Dylan Welch

meteor shower

a gentle wave

wets our sandals

Another non-traditional haiku that eschews the 5-7-5, Welch’s entry here is a snapshot of a rare moment shared between the speaker and someone else. The order of the three images creates a sense of the poet lowering their eyes from shooting stars in the sky, before settling on a strangely intimate image of sitting on the beach. With all the wonders of the universe, nothing compares to a moment shared with someone close to you.

17. “[The west wind whispered]” by R.M. Hansard

The west wind whispered,

And touched the eyelids of spring:

Her eyes, Primroses.

By personifying the whispering ‘west wind’, R.M. Hansard gives life and agency to the natural world. Add in a second protagonist, the primrose-eye’d spirit of spring, and there we have it: a sensual dance that ushers in the changing of the seasons.

18. “After Killing a Spider” by Masaoka Shiki

After killing

a spider, how lonely I feel

in the cold of night!

Masaoka Shiki’s “After Killing a Spider” is a prime example of haiku’s ability to capture the minutiae of life. Filled with loneliness and regret, After Killing a Spider depicts exactly what it says on the tin. But then it goes further into the speaker’s emotions after the incident — for after killing his only companion, the speaker is left alone in the cold of the night. What’s also interesting is that the first break comes after the word ‘killing’, emphasizing the brutality the speaker felt on performing the act, even if it was just a spider.

19. “[I kill an ant]” by Kato Shuson

I kill an ant

and realize my three children

have been watching.

If you haven't had your fill of bug-killing action, here’s a haiku from Kato Shuson. As with “After killing a spider”, the speaker doesn’t feel remorse at having ended a life — but perhaps regrets allowing their kids to see their savage tendencies. Though short in length, this haiku imparts a powerful message: be the person that you want your children to see.

20. “Over The Wintry” by Natsume Sōse

Over the wintry

forest, winds howl in rage

with no leaves to blow.

One can easily imagine the person represented by the metaphorical wind in this haiku: someone in their winter years, who has spent the year railing against the world, only to be left with no one left to listen. While spring often represents the idea of hope in poetry, winter surely is the season of regret.

21. “[cherry blossoms]” by Kobayashi Issa

cherry blossoms

fall! fall!

enough to fill my belly

Cherry blossoms are a big deal in Japan, so it’s no surprise that they often turn up in haiku. In this poem, the cherry blossom festival must be in full swing, and the speaker can barely control their excitement, wishing for more — an excess of it that, surfeiting, the appetite might sicken and so die (as Shakespeare might say). It’s enough to make you want to book the next available flight to Tokyo.

22. “[The lamp once out]” by Natsume Soseki

The lamp once out

Cool stars enter

The window frame.

This is a classic by Natsume Soseki, a widely respected novelist and haiku writer. You might read it literally, thinking that one can marvel at the night sky in all of its wonder as soon as the light of the lamp on the street goes out, or you can also interpret the lamp as an active mind 一 only when we manage to quiet it can we access a deeper, wiser source of light, represented by the stars.

23. “[The snow of yesterday]” by Gozan

The snow of yesterday

That fell like cherry blossoms

Is water once again

As you might have noticed, the art of writing haiku demands an almost superhuman level of observation. Aida Bunnosuke, also known as Gozan, speaks about the impermanence of our surroundings by noticing how snowflakes turn into water in very little time. This theme of the ephemeral nature of life is again emphasized by the cherry blossoms, which only last for about a week after peak bloom.

24. “[First autumn morning]” by Murakami Kijo

First autumn morning

the mirror I stare into

shows my father's face.

Born in Tokyo in 1865, Murakami Kijo helped with the founding of Hototogisu, a literary magazine responsible for popularizing the modern haiku in Japan. In this particular piece, Kijo uses the simple act of looking into the mirror to convey one’s struggle with mortality.

25. “[Just friends:]” by Alexis Rotella

Just friends:

he watches my gauze dress

blowing on the line.

Contemporary poet Alexis Rotella knows how to tap into common human experiences — like, for instance, a friendship that gets in the way of love. In an instant, we can feel the frustration for a potential that won’t be expressed, and a desire that won’t be satisfied.

26. “[What is it but a dream?]” by Hakuen Ekaku

What is it but a dream?

The blooming as well

Lasts only seven cycles

This pensive haiku by Hakuen Ekaku broodingly reflects on the theme of death. As haiku writers like to remind us, the blooming of the most beautiful of nature’s occurrences like spring cherry blossom are always temporary. Coincidentally, Hakuen’s life also spanned seven cycles, as he died at the age of sixty-six.

27. “[Even in Kyoto,]” by Kobayashi Issa

Even in Kyoto,

Hearing the cuckoo’s cry,

I long for Kyoto

In this classic piece by Kobayashi Issa, a bird’s call brings him back to his early days as a student in Kyoto. The poem exudes a certain nostalgia and longing for that time in his life which is now lost 一 something we can all relate to, in our own ways.

28. “[The crow has flown away:]” by Natsume Soseki

The crow has flown away:

Swaying in the evening sun,

A leafless tree

The changing of the seasons is a theme common to Zen Buddhist philosophy, and its influence can be felt in many haiku. Through a series of simple yet provocative images, Natsume Soseki captures the seamless shift as the summer sun sets to make way for the ‘leafless’ fall.

29. “[The neighing horses]” by Richard Wright

The neighing horses

are causing echoing neighs

in neighboring barns

African American novelist and poet Richard Wright often used the ‘haiku round’, a technique where the reader can go back to the first line from the third, as if repeating the poem in endless loops. Try it with this one! Fun fact: according to his daughter, he would draft his poems on disposable napkins before transferring them to paper.

30. “[Lily:]” by Nick Virgilio

out of the water

out of itself

One of the most celebrated English-language haiku, this poem from Nick Virgilio demonstrates the effectiveness of the kireji, or the cutting word which helps the haiku ‘cut’ through space and time. Here, the abrupt colon after “Lily” allows the reader to fill in the gaps in search of the deeper meaning implied.

31. “Childless woman” by Hattori Ransetsu

The childless woman,

how tenderly she caresses

homeless dolls …

An Edo-period samurai who became a poet under the tutelage of Matsuo Bashō, Ransetsu is not usually considered a heavy-hitter in the history of the haiku. He did, however, have his moments, including this piece — a melancholy portrait that is very much the For sale: baby shoes, never worn of its era.

32. “[A raindrop from]” by Jack Kerouac

A raindrop from

Fell in my beer

While most Japanese haiku poems speak of humankind’s harmonious relationship with nature, Jack Kerouac’s contributions to the oeuvre put man and nature on opposing sides. After sketching an image that could easily have come from a pastoral scene — a raindrop fall from a roof — Keruoac pulls back to reveal the modern context. Representative of Kerouac’s caustic writing style, we find that nature disrupts — rather than soothes — the speaker.

33. “[I was in that fire]” by Andrew Mancinelli

I was in that fire,

The room was dark and somber.

I sleep peacefully.

The first line of Andrew Mancinelli’s haiku certainly packs a powerful punch. Was it a real ‘fire’ that our speaker was in, or a metaphorical one in their life? Have they overcome a tragedy and learned that all things must pass — or do they now “sleep,” perchance to dream, in a place beyond that mortal coil? In either case, it’s chilling stuff!

34. “[Plum flower temple:]” by Natsume Soseki

Plum flower temple:

Voices rise

From the foothills

Natsume Soseki was known for weaving fairy tales into his haikus, and this work is a perfect example. Through the myth-like depiction of the ‘plum flower temple’ or the unknown voices rising from the foothills, he creates a sense of wonder for the enigmas hidden in the world around us.

35. “[The first soft snow:]” by Matsuo Bashō

The first soft snow:

leaves of the awed jonquil

This piece by Matsuo Bashō is another ode to the power of nature. You almost sense a certain reverence in the ‘awed’ jonquil leaves that ‘bow low’ to the snow — a reminder that all life, however beautiful, eventually gives way to nature.

36. “[A caterpillar,]” by Matsuo Bashō

A caterpillar,

this deep in fall –

still not a butterfly.

Matsuo Bashō’s brilliance is captured in this simple haiku, which fully immerses you into the perspective of a caterpillar In just three lines. The way in which Bashō depicts the impatient caterpillar conveys a feeling of frustration and desire for growth. In doing so, we realize the angst of unrealized potential.

37. “[On the one-ton temple bell]” by Taniguchi Buson

On the one-ton temple bell

A moonmoth, folded into sleep,

Sits still.

Consider the sound that a ‘one-ton temple bell’ might make if it were to ring. That’s what Taniguchi Buson urges us to imagine, juxtaposing this deep bell against the silent moonmoth, unaware that it might be violently distrubed at any possible moment.

38. “[losing its name]” by John Sandbach

losing its name

enters the sea

As the river gives up its very identity to contribute to the sea, it reminds us of the importance of selflessness. After all, “no man is an island” and we are all parts of a bigger whole, aren’t we?

39. “[Grasses wilt:]” by Yamaguchi Seishi

Grasses wilt:

the braking locomotive

grinds to a halt.

A wilting grass and a braking locomotive: by juxtaposing the two, the poet has created a power dynamic between the images 一 one natural and one man-made. As the grass by the side of the tracks have wilted into the path of the locomotive, the poem suggests that even the mightiest of technological innovations must yield to nature.

40. “[Everything I touch]” by Kobayashi Issa

Everything I touch

with tenderness, alas,

pricks like a bramble

No, not the Britney Spears song! Instead, the author Everything I touch speaks about the tangible pain he feels every time he seeks a kindred contact. Through only three lines, he conveys the wounds of love — and the unforgiving ache of connection.

If these haikus have unlocked the deep thinker and poet in you, you can learn how to write a haiku yourself, or turn to our post on 40 Transformative Poems About Life.

Continue reading

More posts from across the blog.

Goodreads vs. StoryGraph: Which is Better in 2024?

Making the switch to StoryGraph might seem daunting, but if you’ve found yourself frustrated with Goodreads, then it's worth taking the time to jump ship! StoryGraph is an excellent alternative and is in many ways better than Goodreads.

33 Best Vampire Books to Sink Your Teeth Into

From the reported reboot of Buffy the Vampire Slayer to the explosive success of Twilight, there’s no question about it: vampires are “in” right now. At once dangerous, bloodthirsty, and sensual, vampires are the perfect villains to mesmerize both protagonists an...

Guide to African American Literature: 30 Must-Read Books from the Past Century

Want to dive into African American literature? In this post, we’ll take you through 30 essential works, from classic novels ripe for rediscovery to contemporary collections on the cutting edge of literary fiction.

Heard about Reedsy Discovery?

Trust real people, not robots, to give you book recommendations.

Or sign up with an

Or sign up with your social account

- Submit your book

- Reviewer directory

We made a writing app for you

Yes, you! Write. Format. Export for ebook and print. 100% free, always.

Haiku: A Whole Lot More Than 5-7-5 And the 5-7-5 rule doesn't work the way you think

October 10, 2017 • words written by Jack • Art by Aya Francisco

In the spring of 1686, Matsuo Bashō wrote one of the world's best known poems:

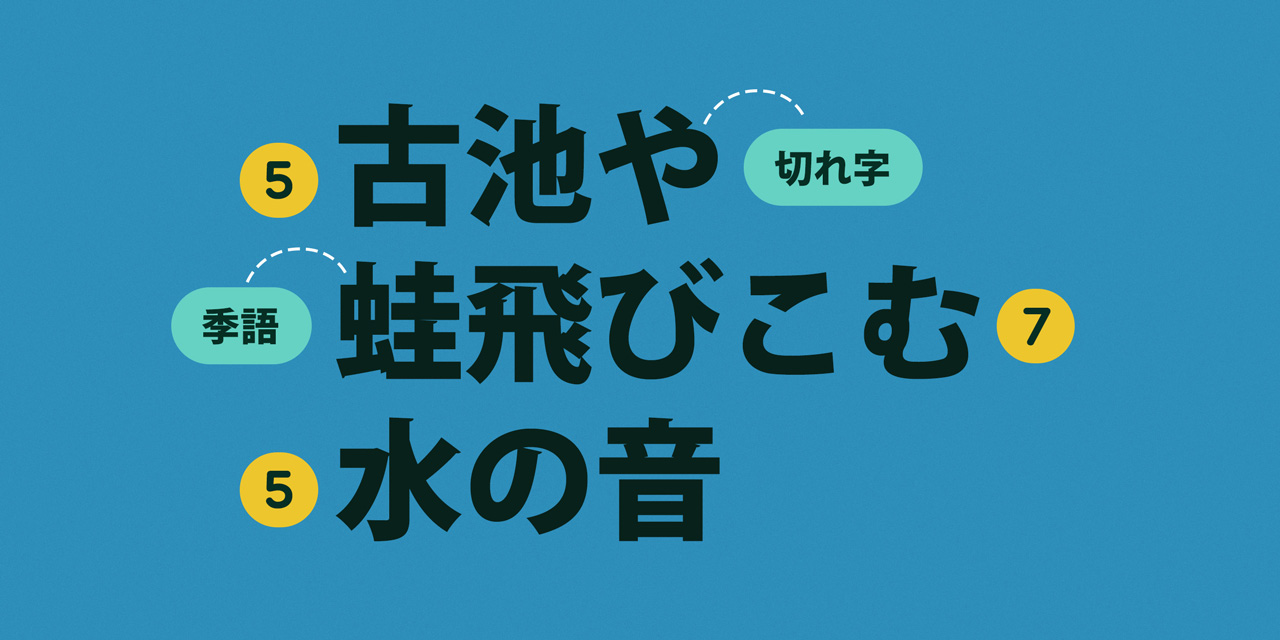

古池や蛙飛びこむ水の音 — 松尾芭蕉 Old pond Frog jumps in Sound of water 1 — Matsuo Bashō

This was a haiku 俳句 ( はいく ) , a short Japanese poem that presents the world objectively and contrasts two different images.

While Bashō wasn't the first to write haiku, this poem became the model that all haiku would be compared against and defined the form as we know it today.

But a haiku is more than just a poem that follows the skeleton of Old Pond. Let's start with a simple definition of what exactly a haiku is and go from there.

Prerequisite: This article is going to use hiragana, one of Japan's two phonetic alphabets, so if you don't know it yet, or just need a review, take a look at our hiragana guide !

What is Haiku?

5-7-5 structure, blurring of subject and object, genuine feeling, egolessness, before bashō, matsuo bashō, kobayashi issa, masaoka shiki, after shiki, what is the future of haiku.

The definition of a haiku in English is usually something similar to this: a poem that has three lines with a 5-7-5 syllable pattern.

But there's much more than that, especially in the syllable department. Let's make it easier by breaking the actual features of haiku into two groups:

Rules are what a poem needs to be considered a haiku. But as with all forms of art, these rules can be bent and sometimes broken for artistic effect.

Qualities are what separate a "good" haiku from a "bad" haiku. It's how you know who's a pro and who's a haiku scrub.

These are just my personal haiku definitions, so it's very likely you'll come across different distinctions and opinions on what makes or breaks haiku. It's a big topic, with a gargantuan history, so there's plenty of room to debate.

Let's begin by looking at the first feature: rules.

The Rules of Haiku

There are three basic rules for writing haiku:

- Seasonal Elements

- A "Cutting" Word

Each has its own important place in the anatomy of haiku.

The 5-7-5 structure is definitely the most well known characteristic of haiku. It's also the one that's broken the most. In fact, a scholar named Harold Gould Henderson (founder of the Haiku Society of America) estimated that about one in twenty classical haiku actually break the 5-7-5 rule. 2

Now, most English speakers learn that this structure refers to syllables. Letting you create cute a little haiku like:

Every day I wake And review WaniKani I know kanji now

But the English concept of syllables doesn't exist in the same way in Japanese.

Instead of a "syllable," which is usually based around a vowel, Japanese has a slightly different concept called on 音 ( おん ) . Linguists refer to this in English as "mora" or "morae" (if there's more than one) and モーラ in Japanese.

In Japanese outside of haiku you may see these on referred to as haku 拍 ( はく ) . But for our poetic purposes, we're going to stick with on .

Similar to the English syllable, a Japanese on measures a chunk of sound . And thanks to the way the Japanese writing systems work ( thank you kana ), these are very easy to understand once you know the rules.

- Each kana character is one on . This includes vowels.

- Contractions containing small kana count as one on .

Let's look at some examples:

A kana character like こ counts as just one on . Then when you add う to it to make it こう it becomes two on . In English, even though this is two kana characters and two on , we wouldn't distinguish the long こう sound as more than one syllable. To us, it's just a long vowel. So we think of it as just one syllable.

A kana contraction like きょ counts as just one on . That's because in Japanese, we think of small ゃゅょ as a part of the character that comes before it. Then when you add う to it to make きょう it becomes two on . In English, this is still just one syllable because to us きょう sounds like one long vowel after a consonant.

However the small っ does not get included in the on that comes before it. So やった has three on and, in English, two syllables.

The ん also counts as one on , if you were wondering. Which would seem very strange in English considering it's just the nasal n sound. But it's a kana in its own right, so it gets to count as one.

Below are a few real word examples, showing how sometimes the number of on and the number of syllables can be the same, and sometimes they don't match at all.

This would be cut and dry if haiku wasn't poetry and poetry wasn't art. Because there is always room for stylistic diversion and change, people can (and do) choose whether or not they count small kana (ゃゅょっ) as on . And just like English poetry, these don't always match with the style.

This can also be heard in Japanese music. Singers typically sing out the "extra" kana that you normally wouldn't hear if someone was just reading the lyrics out loud. But not always. It all depends on how it fits in the song.

However, in general, haiku should be three lines of 5-7-5 on . Let's take a look at a real haiku poem by Tagami Kikusha (田上菊舎), translated by former European haiku expert, Reginald Horace Blyth (R. H. Blyth), broken up into this on versus syllable style.

Remember, the syllables are counting the Japanese poem by English syllable standards, not the English translation.

Anyway, by Japanese standards this is a perfectly straightforward, well-structured haiku, but from the English syllable perspective it's not. So saying haiku is a 5-7-5 syllable structure just isn't true.

And because on are easy to see and count, Japanese haiku are generally written on a single line, rather than broken up into three, which means it's up to the reader to decide where those line "divisions" actually are. It's usually pretty clear, but this also opens up more formatting possibilities.

The 5-7-5 pattern underpins a lot of Japanese poetry. It's like iambic pentameter in English; the language naturally falls into this pattern, so verse was based on it for centuries before haiku existed.

However, as I said earlier, this rule is often broken (in English and Japanese). Here's an example from one of Matsuo Bashō's most famous haiku:

枯枝に烏のとまりけり秋の暮 — 松尾芭蕉 On a withered branch A crow has stopped Autumn evening — Matsuo Bashō

This poem was the first of Bashō's "new style" and it's 5-9-5. Even he broke the rule!

However, I still count this as a rule, not simply a quality of haiku, because it is obeyed most of the time. And when it's broken, it's usually for artistic effect, rather than incompetence.

Haiku are often considered nature poems. Look at any classical haiku and you'll usually see some kind of natural imagery like wildlife or weather. This is more formal than something like a sonnet, that should be about love but isn't always—haiku have specific words you have to use .

These are called kigo 季語 ( きご ) , or seasonal words. In our Bashō example, the kigo is the frog, which represents spring. Some kigo may seem more obvious than others, but they are all rooted deeply in Japanese culture. It isn't as simple as thinking about spring and writing it all down.

Another important mechanic of kigo is that they can be modified. For example, tsuki 月 ( つき ) (moon) is normally an autumn kigo , like in Takarai Kikaku's poem:

蜻蛉や狂ひしつまる三日の月 — 宝井其角 The dragonflies Cease their mad flight As the crescent moon rises. — Takarai Kikaku (Trans. R. H. Blyth)

But, you could write kangetsu 寒月 ( かんげつ ) (winter moon) to make a winter haiku. Yosa Buson does this:

寒月に木を割る寺の男かな — 与謝蕪村 The old man of the temple, Splitting wood In the winter moonlight. — Yosa Buson (Trans. R. H. Blyth)

So there are many, many kigo and they can be altered in many, many ways as long as they follow the rules of appearing where and when they're supposed to.

But how do you know what image goes with what season? There are tons of kigo, so even professionals need some help. All kigo are formally recorded in a saijiki 歳時記 ( さいじき ) , a book used by haiku writers to find the right seasonal word they want to use. These anthologies are often divided into five seasons: spring, summer, autumn, winter, and New Year.

Let's look at some examples to see what we might expect from each season.

繰り返し麦の畝縫ふ胡蝶哉 — 河合曾良 Weaving back and forth Through the lines of wheat A butterfly — Kawai Sora

Many spring haiku treat this time with lightness, joy, and comfort.

Spring is the season of new beginnings. The New Year has passed and plants and animals awaken to fill the world with noise, color, and smells. The days are still hazy, especially in early spring, but we haven't yet hit the oppressive summer heat.

Many spring haiku treat this time with lightness, joy, and comfort—in Sora's haiku, farming mirrors the movement of a butterfly as both begin life anew.

Other things to expect in spring are frogs (as in Bashō's poem), the uguisu 鶯 ( うぐいす ) (Japanese bush warbler), and of course plenty of flowers. Spring is the time for cherry blossoms, plum blossoms, and camellia flowers.

Also, spring is when cats get it on. There are a lot of humorous haiku about noisy felines shamelessly enjoying the season outside a poet's window.

夕立にうたるゝ鯉のあたまかな — 正岡子規 Summer shower Beats the heads Of carp — Masaoka Shiki

Summer opens with thumping rain at the beginning of June and it hits everything, even the water dwelling carp.

Summer weather also means hot days and cool nights. Daytime laziness and nighttime activity are often front and center in summer haiku.

Blyth says, "fields and mountains have in summer a vast, overarching meaning, something of infinity and eternity in them that no other season bestows."

Summer also welcomes the migration of the hototogisu 不如帰 ( ほととぎす ) (Japanese cuckoo), that sings a melancholy tune at night in the mountains.

Insects make appearances in summer haiku as well, and not just fireflies and cicadas either. Mosquitoes, fleas, and lice are all featured. It's common for haiku to treat insects with Buddha-like compassion rather than the annoyance that many of us feel.

砕けても砕けてもあり水の月 — 上田聴秋 The moon in the water; Broken and broken again, Still it is there — Ueda Chōshū (Trans. R. H. Blyth)

Autumn is the perfect time of year for Japanese art – it's excellent at capturing the melancholic beauty of things fading away.

For me, autumn is the perfect time of year for Japanese art—it's excellent at capturing the melancholic beauty of things fading away. Death isn't often featured in haiku, but autumn evenings are used to reflect on the mortality or flaws of man.

It's not all sitting alone feeling glum though. The Milky Way is most visible in autumn. The moon is the clearest symbol of the season, ever present in the haiku tradition as it is in Chōshū's poem above.

Both Chinese and Japanese poetry discuss the sounds of insects in autumn evenings. Haiku adds scarecrows and many flowers, most notably chrysanthemums, to the kigo list.

冬川や家鴨四五羽に足らぬ水 — 正岡子規 The winter river: Not enough water For four or five ducks. — Masaoka Shiki (Trans. R. H. Blyth)

Winter is, of course, a cold season. Even where it doesn't snow, everything becomes more monochromatic and flat. Snow is like winter's cherry blossoms, ever-present and flexible. It covers everything; though pine trees are less affected by the cold than others.

Expect to see tangled twigs and empty fields, with few signs of life beyond fish, owls, eagles, and water birds.

In the lunar calendar, winter is the end of the year, and this sense of finality will sometimes make its way into haiku written for the season.

元朝の見るものにせむ富士の山 — 山崎宗鑑 New Year's Morning The best sight shall be Mount Fuji — Yamazaki Sōkan

Before the Meiji Restoration , the Japanese calendar followed the Chinese lunar year rather than the Western Gregorian calendar. This meant the New Year fell right at the overlap between winter and spring, generally in early February. Plums are beginning to bloom and the sky is turning blue.

In particular, New Year's Morning is considered the beginning of the year—the first experiences of familiar things like the wind, running water, and clouds have a special significance on this day. A view of Mt. Fuji is like this; something seen every day but made more special thanks to the circumstances.

Alternative Kigo

Like 5-7-5, the kigo rule can be broken. Bashō wrote this season-less haiku about the Musashi Plain, now part of the present-day Tokyo Metropolis. In his time it was a vast wilderness.

武蔵野やさわるものなき君の笠 — 松尾芭蕉 The Great Musashi Plain; There is nothing To touch your kasa — Matsuo Bashō (Trans. R. H. Blyth)

The size and desolation of the plain was likely the reason for this haiku's lack of kigo. Regardless of when you walk through it, it will be the same huge, empty place.

Bashō's Musashi Plain haiku is a good example of how the form can be used to encapsulate places. Bashō was known for his travel journals and took many journeys across Japan. Many others followed his lead, and because of this haiku has become associated with travel writing.

Traveling poets weren't just wandering though. They had specific places they wanted to visit, and would write haiku about their experience of that place. It's partially a case of recording their own feelings, but it's also a link between different poets. Writing a poem, following the same themes as those that came before, added that poet to a long tradition.

And just like seasons have kigo, places have seasons you should visit them in and certain aspects you should write about when you're there.

Bashō turned this on its head when visiting the famous islands of Matsushima with his haiku:

松島や ああ、松島や 松島や — 松尾芭蕉 Matsushima… Ah! Matsushima… Matsushima… — Matsuo Bashō

This poem is often read as a refusal to engage in tired representations of the famously beautiful place, but probably shouldn't be taken too seriously—it's also suggested that Bashō just couldn't find the words to express what he'd seen.

In a sense, then, places and place names can act like a kind of kigo in that they link poems together across time and space.

The use of a cutting word, called kireji 切れ字 ( き じ ) is the final "rule" of haiku writing. It's also one of the hardest to translate because there's no direct equivalent in English, or most other languages.

Kireji act like punctuation in haiku. Classical Japanese , like Chinese, uses almost no punctuation beyond a full stop, so haiku use words to do this job instead. More specifically, they use particles.

Some of these are used in standard spoken Japanese, but in haiku their meanings are often quite different. Particularly with common ones, like や and かな , they've actually lost meaning, or rather become undefinable because they're so common.

Here's the most common kireji to look out for:

Meaning is more difficult with kireji, especially because many of them are simply used to add emphasis. Most will be translated in English as:

So if kireji are like punctuation, what exactly are they punctuating? Well, one of the foundations of haiku is juxtaposition. This is the act of taking different things (often visual images in haiku) and placing them close together. This divides and unites at the same time. Let's look at my personal favorite haiku, by Issa:

遠山や目玉に写るとんぼかな — 小林一茶 Distant mountains Reflected in the eyes Of a dragonfly — Kobayashi Issa

Issa creates a dizzying effect of space using the difference in scale between the mountains and how they appear in the dragonfly's compound eyes. This is juxtaposition, and it's fundamental for haiku.

Here the kireji is either や at the end of the first line or かな at the end of the third. や emphasizes the mountain, while かな emphasizes the dragonfly. This means that the two main elements sit at either end of the poem. In the middle is 目玉 ( めだま ) に 写る ( うつ ) , the reflection literally sits between and joins the two images.

Kireji mark emphasis and juxtaposition and the cut (切れ) is the change in focus from one thing to another. Your choice of kireji and where you put it can affect how this cut works. Haiku relies on creating associations, and the best are often interesting or powerful.

For Bashō's frog haiku, the kireji や is at the end of the first section. So we might split the poem into two parts:

古池や 蛙飛び込む水の音 — 松尾芭蕉 Old pond Frog jumps in, sound of water — Matsuo Bashō

Putting the や there marks the old pond as the setting for the action of the frog. We move from ancient stillness to movement as we cross the や cut.

An interesting side note: Bashō reportedly wrote the second part of this poem first, and went through numerous revisions before setting on 古池や. For this haiku, at least, the two-part structure was fundamental.

Issa's dragonfly haiku uses a different cutting technique. Placing かな at the end of the poem creates a cyclical effect, but also means the poem's cut is between its end and its beginning.

Because of this, the two images of the mountains, even though their sizes are very different, are unified by the かな, that also cuts off the end of the poem. Combine that with the linking we discussed above and you can see how full of connections Issa's poem is.

Kireji and juxtaposition are arguably the most important aspect of haiku, especially today. Even though they can't really be translated, the effect is essential in any language. It's also notable that while modern gendai haiku 現代俳句 ( げんだいはいく ) tend to ignore 5-7-5 and kigo rules, it's rare to see them without kireji or at least the cutting feeling.

Qualities of Haiku

So those are the rules that all haiku must at least be conscious of. But like I said, not all haiku have to follow them, and when they don't it's always a purposeful decision.

But there is more to haiku than just following rules. Good haiku are thought to be made up of qualities, and we'll be going through those next. Those qualities are:

- A blurring of subject and object

Just like we did with the rules, let's tackle these one at a time.

This quality is so common it's arguably a rule. Haiku is often critiqued along the line of subject (the thing doing) and object (the thing being done to). To understand why, we'll need some history.

Haiku as we know it is a reaction to the waka 和歌 ( わか ) poetry of the medieval Japanese court. At that time, poetry was often an exercise in wit rather than emotion. Juxtapositions could get tired, or even silly, as more and more people used them as a way to show off.

By Bashō's time, the "show off" poem had reached a fever pitch, and Bashō's insistence on objective presentation was an attempt at fighting back. We'll see later, he wasn't the first to do this, but he definitely became the most influential.

If the poet presents something objectively, they can get mixed in with the scene even if they aren't explicitly described. Issa's presence is needed to see the mountains in the dragonfly's eyes, for example. But by avoiding too much wit, and being careful about describing yourself, you can make it so that you are part of the scene, rather than imposing yourself on it.

In this way, subject and object are blurred. Is Bashō the subject or the object? What about the frog? The frog is affecting both the water and Bashō, so maybe it is the subject and Bashō or the water are the objects. But Bashō is there, watching the frog and (obviously) describing the scene. Then he must be the subject and the frog is the object.

Haiku is often critiqued along the line of subject (the thing doing) and object (the thing being done to).

Confused? That's because the subject and object of the haiku are objective: the poet and the frog and almost everything else in the poem occupy both the subject and object space simultaneously.

This principle is linked in with Zen—humans are not rulers of Nature, or even a part of Nature, but we (along with everything else) are Nature.

Blyth takes the blurred boundary a step further and argues the Japanese language itself is excellent for mixing subject and object. This is partially due to the fact that Japanese tends to leave out pronouns and subjects, and because word order is fairly flexible. Verbs can apply to several things at once, especially if you fiddle with the particles.

Also, the brevity of haiku means the reader becomes the writer too. If Bashō only gives you:

古池や Old pond

Then it's up to you to decide what this scene actually looks like. Are there trees around? Where's the pond? What's the weather like? How deep is it? What you picture, whether it's conscious or not, makes you a part of the process.

Singular and plural are also rarely defined. Do you want one mountain reflected in one dragonfly's eye, or several in a whole swarm? One frog, two, or seven?

Haiku deals mostly with visuals but tells little, so the reader takes an active role, also becoming subject and object. The reader isn't just the object acted upon by the poem, but also the subject that creates the feeling felt by the poet.

For all of these reasons, translations of haiku can vary enormously. To stick with our Bashō example, let's look at some different translator's interpretations:

Old dark sleepy pool quick unexpected frog goes plop! Watersplash. (Trans. Peter Beilenson)

Old pond — frogs jumped in — sound of water. (Trans. Lafcadio Hearn)

dark old pond : a frog plunks in (Trans: Dick Bakken)

As you can see, just because the language used in haiku is generally simple, it doesn't mean the images being transmitted are necessarily fixed. The subject and the object blur and shift.

Let's take a look at a few haiku that do this well, and some that don't.

やれ打つな蝿か手をする足をする — 小林一茶 Don't kill the fly! He is waving his arms, His legs — Kobayashi Issa

This is one of Issa's most famous haiku. He was known for his depth of feeling, especially toward animals. But this poem has also been criticized for this very quality. Issa can sometimes get too involved in his subject, and here we arguably feel his worry and anger too much.

月に柄をさしたらばよき団扇かな — 山崎宗鑑 A handle On the moon — And what a splendid fan — Yamazaki Sōkan (Trans. R. H. Blyth)

This well-known haiku gives us a striking image. Watching the full moon, Sōkan sees its round shape and imagines it as a circular uchiwa 団扇 ( うちわ ) fan. It's one of my personal favorites, but the subjectivity is explicit. The poem describes someone imagining the moon as a fan, rather than just presenting the two images together for the reader to put together on their own.

案山子から案山子へ渡る雀哉 — 巖谷小波 Sparrows fly From scarecrow To scarecrow — Iwaya Sazanami

Sazanami's poem gives us no hint at all to the poet's feelings. It's absolutely a stated fact, and one we have to interpret for ourselves. As with many of the most objective examples, it's only the kireji, 哉 that even tells us someone is watching. This wonder is Sazanami's, but we can never know exactly what kind of wonder it was.

As I mentioned above, haiku was intended (by Bashō at least) to record a genuine and spiritual feeling, rather than show off. Teitoku is considered one of the worst offenders of this:

哀なる事 聞せばや ほとゝぎす — 松永貞徳 A sad tale? Is that what you want cuckoo? — Matsunaga Teitoku (Trans. Steven D. Carter)

This verse plays on the sad tune of the hototogisu cuckoo flying around at night. While this in itself isn't a problem, the verse reduces the cuckoo to nothing but sadness.

What's worse, it's actually about the poet and his sad tale, rather than the bird. It's like the bird has interrupted him while talking to friends, and he's shouting this poem out the window at it. There's no unity with nature or humility that later poets would consider essential to haiku.

It's important to note you don't usually criticize a haiku for which feeling it demonstrates, because that isn't always clear. If a poet is objective, then they shouldn't be telling us. Imagine how clunky Issa would be if he wrote:

Distant mountains Reflected in the eye Of a dragonfly Made me feel really small and insignificant compared to the world

Instead, we need to see the intensity of the feeling, and by the images, judge what might be felt. There are still conventions about subject, but by Shiki's time these were much less important. Today you can write your haiku about love, or sex, or disaster, or death, if you want, but you'll need to be careful to keep things small and objective.

An insistence on genuine feeling doesn't mean haiku can't have humor. Buson is a great one for this:

春雨や蛙の腹はまだぬれず — 与謝蕪村 Spring rain The frogs' bellies Aren't yet wet — Yosa Buson

He also plays with language a lot:

日は日くれよ夜はや明けよと啼く蛙 — 与謝蕪村 By day, "Day go away!" By night, "Night, turn to light!" — That's what Croaking frogs say — Yosa Buson (Trans. Henderson)

Blyth in particular stresses the importance of onomatopoeia and sound in haiku, and Buson is probably the best for it. He's also the opposite of Bashō in many ways, less serious and more experimental.

As before, here are a few more examples of haiku that manage to be genuine and powerful, and some that fall short.

蛤の二見に別れ行く秋ぞ — 松尾芭蕉 Autumn Parting as we go, clams opening To Futami — Matsuo Bashō (Trans. R. H. Blyth)

Blyth argues that "this verse has no poetical value beyond the puns in it." The open clams look like futa 蓋 ( ふた ) (lids), and symbolize the parting of friends, and the 行く ( い ) refers both to the people and autumn itself.

Although the feeling might have been strong for Bashō, the execution feels more like the type of poetry he tried to move away from.

蚤どもゝ夜永だらうぞ淋しかろ — 小林一茶 For you fleas too, The night must be long, It must be lonely. — Kobayashi Issa (Trans. R. H. Blyth)

Fleas are a common topic for Issa, and fit well with his love for animals, no matter how small. This verse arguably fails to be a true haiku on account of its moralizing, but it's difficult to argue that Issa doesn't feel genuine kinship with the insects in his hut.

行衛無き蟻の住居やさつき雨 — 久村暁台 Nowhere to go; The dwellings of ants In the summer rain. — Kumura Kyōtai (Trans. R. H. Blyth)

This verse mixes the objective description we discussed earlier with a strong pathos. Even though it isn't present in the poem itself, we can't help but feel for the ants as the rain pours in. Kyōtai must have felt this too, and transmits it indirectly through the images.

Egolessness is linked to the other two qualities, subject/object blurring and genuine feeling. But I'm counting it as its own thing because it's more like the attitude behind both of them.

I said earlier that the poet is present in a haiku even if they aren't mentioned. This is true, but even if they are mentioned, they should still strive for egolessness. Meaning the poet is part of the scene, not dominating or creating it.

Egolessness is an important quality for Bashō and a number of other poets in the Zen Buddhist tradition. Mu 無 ( む ) (nothingness) is an important Buddhist concept. In short, one should aim to remove their "self" in order to recognize they are one with the world and Nature. Haiku is often considered a good vehicle for expressing this.

Bashō described a technique called hosomi ほそみ ( ) (thinness). ほそみ is described by Makoto Ueda, a Stanford University haiku expert, as where "the poet buries himself in an external object with delicate sensitivity."

An example of this is:

塩鯛の歯ぐきも寒し魚の店 — 松尾芭蕉 A salted sea-bream, Showing its teeth, lies chilly At the fish shop — Matsuo Bashō (Trans. Ueda)

Bashō feels the coldness of the dead fish like it were his own. The whole time he stands nearby, admiring its teeth.

The "thinness" itself refers to the lines between images or objects—they have to be linked by the poem, but subtle linking leads to thinner, better lines. It's more than just empathy, but a specifically Zen feeling of unity with the subjects of a poem.

Egolessness is one of the more controversial qualities on this list. Zen and haiku are often considered to go hand-in-hand, but many poets had no special affiliation with the philosophy. Buson, while he may be genuine, is often considered the subjective, personal counterweight to the sometimes objective, cold Bashō. Sometimes his humor and skill can feel like showing off.

茸狩や頭を挙れば峰の月 — 与謝蕪村 Mushroom hunting Assembled by my head Moon on the peak — Yosa Buson

Haiku don't have to be based on real scenes. It's perfectly fine for a poet to imagine something then make it into a haiku. But a criticism of Buson's poem above could be that it foregrounds the artistry too much.

Traditionally, haiku are considered "best" when they appear completely natural and spontaneous—this is part of the objectivity aspect.

But in this Buson ties together lots of repeated shapes to create a poem full of white circles: the mushrooms, the moon, and his bald head leaning down. This might feel unrefined to those who prefer Bashō's more severe style. But Buson wasn't as troubled by objectivity, and didn't let it get in the way of a good poem. As a result his verses can feel witty or contrived when they don't quite land.

Here's one more egoless poem by Issa:

我と来て遊べや親のない雀 — 小林一茶 Come with me And play, little parentless Sparrow — Kobayashi Issa

Issa is sometimes criticized for being too personal, and feeling the injustice of the world too strongly. Although his desperately sad life gave him good reason for this, his poems often express deep anger, despair, or desolation.

Haiku History

Now that we've covered the broad characteristics of classical haiku, you might be wondering about all the names like "Issa" and "Shiki" I've been throwing around. That's what this section is for: tackling haiku history, especially the "Great Four" haiku poets.

We don't know exactly when the first haiku was written. The earliest examples of haiku-like verses are in the 1235 Hyakunin Isshu 百人一首 ( ) anthology, compiled by Fujiwara no Teika. Here we find:

なる花を追いかけてゆく嵐哉 The falling blossoms Look at them, it is the storm That is chasing them (Trans. Henderson)

If you check the rules we discussed above, it hits every mark. The 5-7-5 pattern is there, it has a kireji (哉) and a kigo (花). It also presents the image more or less objectively.

While these poems certainly existed, we actually need to look at other forms in order to properly understand haiku's heritage. Most importantly waka. This is an ancient form that's recorded as far back as the 8th Century in the Kojiki 古事記 ( ) and Manyōshū 万葉集 ( ) . These are the earliest records of Japanese history and literature we have, so the presence of waka in them is testament to the form's age and importance.

Waka poems use lines of 5-7-5 on , often alternating. The most popular type of waka, the tanka 短歌 ( たんか ) was generally written collaboratively. The first person would write one part of 5-7-5, then a second person would finish it with two lines of 7 each. Making a final result of 5-7-5-7-7 on .

Another collaborative form was the renga 連歌 ( れんが ) . These are chains of three-line poems, some stretching over 100 verses. The first verse, called the hokku 発句 ( ほっく ) (starting verse) would be written by the most senior poet. It was hokku that became haiku as we know it. In fact, the word haiku was only coined by Shiki in the 19th Century—everyone before called their individual poems hokku.

Renga are chains of three-line poems. The first verse, called the hokku (starting verse) would be written by the most senior poet. It was hokku that became haiku as we know it.

Bashō in particular participated in lots of collaborative poetry sessions, and many of his best-known works come from them. This context means, even if a poem was composed in isolation, it was probably a potential starting verse for collaboration.

Renga gained huge popularity in the Kamakura period . There were two defined styles, one "higher" and serious, the other "lower" and more witty.

This lower form was called haikai no renga 俳諧の連歌 ( はいかい れんが ) . The same kanji character 俳 is used in the word haiku 俳句 ( はいく ) to reflect haiku's origins. The meaning of 俳 implies playfulness and lightness, often in the context of mixing contemporary and classical language or images.

One of the most famous poems from this period is by Arakida Moritake (荒木田守武 1473–1549):

落花枝に帰ると見れば胡蝶かな — 荒木田守武 A fallen blossom returning to the bough, I thought— But no, a butterfly. — Arakida Moritake (Trans. Steven Carter)

Moritake's poem has been quoted and studied by everyone from Bashō to Ezra Pound , and is considered one of the first true haiku. Despite this, it's got a personal viewpoint, which means some don't consider it especially "good" by modern standards. This fits better with the playful or witty style of the time, though.

The lower tradition continued. While it tended to avoid the problems of serious verse (you need a good poet to avoid sounding uptight), by the 17th century Henderson describes it as "little more than a parlour game." Teitoku (貞徳 1571–1654) was the foremost amongst these poets:

けさたらるうららやよだれのうしのとし — 松永貞徳 This morning, how Icicles chip! — Slobbering Year of the Cow! — Matsunaga Teitoku (Trans. Henderson)

The link here between cow saliva and icicles is considered too simple, and has no significance beyond the two looking similar. The best haiku often have more to them than drawing comparisons. While Teitoku's disciples were less conceited, Bashō referred to verses like these as "Teitoku's slobber." Haiku at this point were more like contests of wit than "true" artistic expression.

"At last!," I hear you cry. Bashō is the most important haiku poet there is. Period. Though he didn't invent haiku, he changed it so much that everything after him is effectively a response to his work.

Bashō was born Matsuo Kinsaku 松尾金作 in what is now Mie Prefecture, in 1644. His father was likely a low-ranking samurai. In his youth he was made the servant of Tōdō Yoshitada, the son of a local lord. Because Bashō was only a few years younger than his master, the two became more like childhood friends and studied art together. Bashō's first poem was published in 1662, under the pen name Sōbō 宗房.

Tōdō died young, and Bashō was greatly affected by it. He renounced his samurai heritage and began to wander, moving to Kyoto and then Edo (now Tokyo).

By all accounts, Bashō was reasonably well-known and successful as a poet and a poetry teacher. He founded a school at age 30 and worked full-time tutoring his students. His disciples built him a hut made of banana plants, or bashō 芭蕉 ( ばしょう ) , which he took as part of his well-known pen name.

Over his lifetime, there would be three bashō-an 芭蕉庵 ( ばしょうあん ) (Bashō Huts), as a result of fires and his travels in the last ten years of his life. It seems from his poems that he was attached to the plant from the beginning:

ばしょう植ゑてまづ憎む荻の二葉哉 — 松尾芭蕉 By my bashō plant The first thing I hate Miscanthus buds — Matsuo Bashō

When Bashō was 38, he began serious study of Zen, and renounced his life as too worldly. Up to this point he was a successful poet, but nowhere near the level he would become. It was after his change that his "new style" poems began, the first of which is one of his best-known:

枯枝に烏のとまりたるや秋の暮 — 松尾芭蕉 On a withered branch A crow has stopped Autumn evening — Matsuo Bashō

Bashō is the most important haiku poet there is. Period.

Here we have an utterly objective presentation of an image. Not only that, but it creates an entire world behind it, rather than just a pun or clever link. 秋の暮 could also be translated as "the end of autumn," or even "an ending like autumn" if you want to be liberal.

It isn't just a seasonal reference to help a collaborator, but an artistic choice that colors the whole poem. The feeling behind the poem is cloudy and uncertain. As with many haiku, we as readers have to work to construct the significance of the moment described.

From here on, Bashō's output became the definition of haiku. But he didn't stop there. In addition to participating in renga writing sessions and literary criticism, he went on several journeys around Japan. His travel journals used the haibun 俳文 ( はいぶん ) form—haiku and prose together. His best known is Oku no Hosomichi 奥の細道 ( ) ( Narrow Road to the Deep North ), the first few lines of which are commonly memorized by Japanese schoolchildren.

月日は百代の過客にして、行かふ年も又旅人也。舟の上に生涯をうかべ馬の口とらえて老をむかふる物は、日々旅にして、旅を栖とす。古人も多く旅に死せるあり。 — 松尾芭蕉 Days and months are travellers of eternity. So are the years that pass by. Those who steer a boat across the sea, or drive a horse over the earth till they succumb to the weight of years, spend every minute of their lives travelling. There are a great number of ancients, too, who died on the road. I myself have been tempted for a long time by the cloud-moving wind—filled with a strong desire to wander. — Matsuo Bashō (Trans. Nobuyuki Yuasa)

Bashō left behind many disciples, but none reached his level of poetry. He died in 1694, and was deified as a Shinto kami 神 ( かみ ) about 100 years later in 1793.

He didn't write a formal death poem. Instead, he claimed that every poem of his last twenty years were death poems. His last, written the day before he died, is worth mentioning.

旅に病んで夢は枯野をかけ廻る — 松尾芭蕉 Falling sick on a journey My dream wanders around Fields of dry grass — Matsuo Bashō

Yosa Buson (与謝蕪村) is often considered a counterweight to Bashō's style, but he was also a key figure in reviving it. Despite this, it was only through Shiki that he became well-known in the last century.

Buson was born in what is now Osaka as Taniguchi Buson in 1716. He moved to Edo when he was 20 and learned about the Bashō school from Hayano Hajin. After his master's death he traveled in the footsteps of Bashō around northern Japan. He moved around for much of the next 20 years, finally settling in Kyoto at the age of 42.

In Kyoto, Buson became a central figure in the revival of Bashō's style. He built the "Bashō-an," a hut for poetry gatherings, and prepared numerous copies and paintings of the master's work. He died in 1783 and little is known about his life compared to Bashō. Blyth says that at the very least, "he seems to have been a loving husband and devoted father."

Fortunately for us, Buson's poetry speaks for itself. His style is regarded as more painterly, subjective, and brilliant than Bashō's. It draws attention to the fact that poetry is art, rather than avoiding it as Bashō's best poems do.

In other words, you can sometimes "see the brushstrokes" in Buson, but for him this is deliberate rather than a failure to properly imitate reality—he was about as famous a painter as he was a poet, and often combined the two in haiga 俳画 ( はいが ) (verse-painting). Henderson calls Buson, "brilliant and many-sided, not mystic in the least, but intensely clever and alive to impressions."

I've already said haiku are often visual, and haiga puts this at the foreground. But many of Buson's poems focus instead on sound, either in his descriptions or through onomatopoeia. Say this one out loud and feel how the waves wash through your mouth:

春の海ひねもすのたりのたりかな — 与謝蕪村 The spring sea, Gently rising and falling, The whole day long. Yosa Buson (Trans. R. H. Blyth)

He also has a good ear for sounds in the real world:

涼しさや鐘を離るゝかねの聲 — 与謝蕪村 The cool of morning — Separating from the bell, The voice of the bell. Yosa Buson (Trans. Donald Keene)

But Blyth argues that his haiku rarely reach the same soulful depths that Bashō's do. He even says that Buson can have a "greediness for colour," in verses like:

夕顔や黄に咲いたるもあるべかり — 与謝蕪村 Evening-glories; There should be also One blooming yellow Yosa Buson (Trans. R. H. Blyth)

Yosa Buson is often considered a counterweight to Bashō's style, but he was also a key figure in reviving it.

These last two poems are useful to consider in comparison with paintings. Either they heighten the sense of visual imagery, like in the second example, or they balance it with something else, as in the first.

Donald Keene, Japanologist extraordinaire, argues that Buson's visual focus isn't because of a failed imitation of Bashō, but due to Buson's circumstances. The second half of his life saw many natural disasters, most notably the eruption of Mt. Asama that killed 35,000 people. Because of this, most of his haiku are standalone and almost escapist. Bashō, by comparison, can be read chronologically, and often feels much more "in the world." In Keene's words, "for Buson … poetry itself was the world of light, and escape from harsh realities."

Kobayashi Issa 小林一茶 is perhaps the best-loved of the "Great Four." Henderson says he was "not a prophet like Bashō, nor a brilliant craftsman like Buson; he was just a very human man."

Born in 1763 in what is now Nagano Prefecture, Issa (then called Nobuyuki) led a desperately sad life. His mother died when he was three years old, and the young Issa wasn't liked by his stepmother.

His father died when Issa was in his late twenties. Legal battles over his inheritance would continue for decades, and as far as we know he lived in poverty with no true home until he was nearly 50.

In the next 10 years, he would suffer the deaths of three of his young children and his first wife. The latter incident caused him to write:

生き残り生き残りたる寒さかな — 小林一茶 Outliving them, Outliving them all, Ah, the cold! — Kobayashi Issa (Trans. R. H. Blyth)

In 1827, the year of his death, a massive fire swept through the village of Kashiwabara, destroying Issa's home and forcing him to live out his final days in his storehouse.

Despite the constant tragedy of Issa's life, he wrote over 20,000 haiku—ten times more than Bashō. His capacity for feeling was enormous, especially compared to the sometimes-distant Bashō or overly-artful Buson. But this can manifest itself in a break from the objectivity we expect from haiku:

庵の蚤不便やいつか痩せる也 — 小林一茶 Fleas of my hut,— I'm sorry for them; They became emaciated soon enough. — Kobayashi Issa (Trans. R. H. Blyth)

This is one of his most famous poems, and demonstrates his capacity for feeling. How many people would write a poem about fleas, let alone one that shows so much empathy for them. Issa wrote about 1,000 verses on small creatures, from flies to frogs to snails, and often feels a great kinship with them.

Issa isn't always sad, though. He shows a great sense of delicate beauty:

芥子さげて群集の中を通りけり — 小林一茶 Making his way through the crowd In his hand A poppy. — Kobayashi Issa (Trans. R. H. Blyth)

And humor too:

人來たら蛙となれよ冷し瓜 — 小林一茶 If anyone comes, Turn into frogs, O cooling melons! — Kobayashi Issa (Trans. R. H. Blyth)

Issa is in many ways more accessible than the others, and allows his feelings to shine through.

Here the sight of melons floating in the water reminds Issa of frogs. Understandably, he's wary of leaving them unguarded, and in this moment the humorous link is born.

Issa is one of the best-loved haiku poets, and the scholarship on him rivals that of Bashō. He is in many ways more accessible than the others, and allows (for better or worse) his feelings to shine through.

He isn't considered as technically proficient as the two before him, and out of his 20,000 poems only a few hundred are really considered excellent.

But he is praised for going his own way rather than imitating. Buson followed Bashō, and Shiki followed Buson, all leaving behind disciples and schools. But Issa was something unique among the Four.

Masaoka Shiki (正岡子規) occupies an interesting place in the Great Four. He is known more as a critic than a poet, although he did plenty of both.

Shiki was born in Matsuyama in what is now Ehime Prefecture in 1867, at the start of the Meiji Restoration . By age 15 he'd been banned from public speaking by the principal of his middle school, and was shaping up to be an opinionated young man.

He moved to Tokyo in 1883 and took a scholarship at Tokyo Imperial University in 1890. He dropped out two years later because he was too focused on writing haiku. But around this time he developed tuberculosis, which would dominate the rest of his life.

He took the pen name Shiki as an alternate reading of 子規 (the hototogisu cuckoo). It was believed cuckoos cough blood when they sing—a reference to his continued illness.

Shiki got work as a correspondent in the Sino-Japanese War, but because of his poor health the experience ended in hospitalization. After being discharged, he moved back to Matsuyama and founded a haiku school.

In 1897, the journal Hototogisu was founded by one of his disciples. Today it's the oldest and most prestigious haiku journals in Japan. By this time, Shiki was bedridden and suffering from an addiction to painkillers. He died in 1902 at the age of 34.

Shiki started writing haiku despite the prevailing sense that it, along with other classical poetic forms, was outdated. After leaving university he started advocating reform, and was quickly offered a position as a haiku editor. His essay A Criticism of Bashō was sacrilegious in its indictment of the master, and caused great controversy.

He claimed that the Bashō school treated Bashō as a saint and all his writing as scripture. Shiki himself believed one hundred or so of Bashō's thousands of verses were great. The rest he dismissed as failures.

Shiki later revised his position, but the essay still showed he was against the reverence of old things just because they are old.

He also stood strongly against linked verse, arguing that only hokku (or as he called them, haiku) were literature. By the Meiji period , linked verse had all but disappeared in favor of standalone haiku, but the practice reinforced the work of almost every haiku poet before this time.

Shiki later revised his position, but the essay still showed he was against reverence of old things just because they are old.

In his other works, he broke with tradition by arguing haiku should be considered alongside other forms of Japanese literature .

Also, Shiki was in favor of realism and observation of nature, rather than what he called, "the puns or fantasies often relied on by the old school." He and his school focused on all feelings, so long as they were genuine, and borrowed a lot from Western realism.

船着きの小き廓や綿の花 — 正岡子規 Near the boat-landing A small licensed enclosure; [i.e. for prostitutes] Cotton-plant flowers — Masaoka Shiki (Trans. R. H. Blyth)

説教に穢れた耳を不如帰 — 正岡子規 The sermon, stale Defiled my ears; but now— The nightingale! — Masaoka Shiki (Trans. Henderson)

翡翠や水澄んで池の魚深し — 正岡子規 The kingfisher: In the clear water of the pond Fishes are deep — Masaoka Shiki (Trans. R. H. Blyth)

And, of course, Shiki was the one to define haiku as its own form: a standalone hokku verse. In doing so, he separated it from its collaborative origins. As an agnostic, his criticism also separated haiku from Buddhism, freeing it up for greater experimentation in the future.

Haiku exploded in popularity after Shiki. Around the time of his death, Japanese poetry was translated into English for the first time, and waves of European writers experimented with the form. In Japan, poets began ignoring the rules that cemented the haiku tradition. Haiku without kigo that entirely ignore the 5-7-5 structure are now common (kireji, or at least juxtaposition, is still mostly respected). Nature is no longer essential in haiku either.

Some examples of these more experimental haiku are:

咳をしても 一人 — 尾崎放哉 Even if I cough, I am alone — Ozaki Hōsai (Trans. Ueda)

戦死者が青き数学より出たり — 杉村聖林子 war dead exit out of a blue mathematics — Sugimura Seirinshi (Trans. Itō Yūki)

ある日笑ひはじめし名なき山 — 鈴木六林男 One day a nameless spring mountain began to smile — Suzuki Murio (Trans. Ban'ya Natsuishi)

暗闇の眼玉濡らさず泳ぐなり — 桂信子 I'm swimming in darkness keeping eyeballs clear — Katsura Nobuko (Trans. Natsuishi)

Haiku is one of the oldest forms of poetry in the world. It's undergone enormous change and revolution over the centuries, and in the last one hundred years has expanded into hundreds of other languages.

The best haiku have always pushed boundaries and reached for something deeper than words themselves. Despite this, they're easy to start writing and enjoyable to read. Why not try writing haiku yourself? Head outside, open your eyes, and write. If you like it, try to incorporate more of the rules. Think of the season. Try to include a cut. Pull yourself out of the scene. And be true to what you feel in the moment.

Translations are the author's unless specified. ↩

"Classical" is generally used to refer to haiku up to Shiki (1867–1902), but might not include Shiki himself depending on who you ask. ↩

- A Guide To Japanese Poetry...

A Guide To Japanese Poetry Forms From Haiku To Waka

Tokyo Writer

In Japan , written poetry can be traced back to the era of the Chinese Tang Dynasty (618–907), and for centuries was the sole prerogative of courtiers and nobles. From then, it evolved into a diverse range of unique styles, invented and standardized throughout the next hundreds of years. Below you’ll find a guide to the most common Japanese poetry forms known today.

Haiku is the quintessential form of Japanese poetry. Haiku was originally referred to as hokku , and was used as the opening stanza of a poem. Eventually, these hokku began to appear as poems in their own right, and were renamed haiku by Masaoka Shiki — a man widely regarded as one of the four great haiku masters — in the late 19th century. A haiku consists of 17 ‘ on ’, or syllables, in a 5-7-5 pattern. A traditional Japanese haiku is printed in one long vertical line, while in English it is split into three horizontal lines.

Kanshi refers to Chinese poetry in general, as well as poetry written in Chinese by Japanese poets. In the Heian Period (794-1185), Chinese was the language of the law and the courts. The kanshi was one of the most popular forms of poetry at the time. Its most pattern was composed of five to seven syllables divided into four or eight lines. The rhyming scheme of the poem was intended to balance the four (plus neutral) Mandarin tones.

Renga is collaborative poetry, meaning it is usually written by at least two authors. It includes at least two stanzas, the opening being the precursor to the modern haiku . As such, the original renga can be simplified as being a haiku , plus a second stanza with a seven and seven syllable count. This is known as the short renga , or tan-renga . Later, during the Edo Period (1603-1868), the rules surrounding renga poetry were relaxed, and a version with 36 verses became the norm, known as a kasen . Classical form did however require a kasen to refer to flowers twice, and the moon three times!

Renku is another form of collaborative poetry. It was a group activity, very casual and sometimes even comically vulgar. The idea of working together to finish an artistic work was very appealing in pre-modern Japan, when many aristocrats and noblemen would exchange poetry with each other as a form of entertainment. At a traditional renku gathering, poets would take turns providing alternating verses consisting of 17 and 14 morae. A mora is a linguistic unit. A long syllable consists of two, and a short syllable consists of one.

Tanka and Waka

Long ago, waka referred to any poetry written in Japanese. During the Heian Period, it was mostly written by women, since the men wrote in Chinese. Tanka simply means short poem, and it falls under the category of waka . It is the most commonly composed type of waka throughout history — other forms of waka , such as the katauta , ceased to be used at the beginning of the Heian Period over one thousand years ago. As a result, waka and tanka have now become synonymous with one another. A tanka consists of five syllable groups, or ‘ on ’, in a 5-7-5-7-7 pattern.

Become a Culture Tripper!

Sign up to our newsletter to save up to $1,656 on our unique trips..

See privacy policy .

Culture Trips launched in 2011 with a simple yet passionate mission: to inspire people to go beyond their boundaries and experience what makes a place, its people and its culture special and meaningful. We are proud that, for more than a decade, millions like you have trusted our award-winning recommendations by people who deeply understand what makes places and communities so special.

Our immersive trips , led by Local Insiders, are once-in-a-lifetime experiences and an invitation to travel the world with like-minded explorers. Our Travel Experts are on hand to help you make perfect memories. All our Trips are suitable for both solo travelers, couples and friends who want to explore the world together.

All our travel guides are curated by the Culture Trip team working in tandem with local experts. From unique experiences to essential tips on how to make the most of your future travels, we’ve got you covered.

Guides & Tips

The best solo trips to take in your 30s.

How to Experience Off-the-Beaten-Track Japan by Bullet Train

The Best Rail Trips to Book this Year

See & Do

The best places to visit with culture trip this autumn.

Introducing Culture Trip's Rail Trips

Film & TV

The best japanese movies to watch on the bullet train.

Rediscover Japan with its Borders Fully Open

Top Tips for Travelling in Japan

How modern art revitalised the city of Towada, Japan

How Much Does a Trip to Japan Cost?

The Ultimate Guide to Getting around Japan

Tomamu: a secret skiing spot in the heart of Hokkaido

Culture trip spring sale, save up to $1,656 on our unique small-group trips limited spots..

- Post ID: 810105

- Sponsored? No

- View Payload

A Guide to Japanese Poetry Forms

Chris M. Arnone

The son of a librarian, Chris M. Arnone's love of books was as inevitable as gravity. He holds an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Missouri - Kansas City. His novel, The Hermes Protocol, was published by Castle Bridge Media in 2023 and the next book in that series is due out in winter 2024. His work can also be found in Adelaide Literary Magazine and FEED Lit Mag. You can find him writing more books, poetry, and acting in Kansas City. You can also follow him on social media ( Facebook , Goodreads , Instagram , Twitter , website ).

View All posts by Chris M. Arnone

We’ve all heard of haiku , but that’s far from the only Japanese poetry form. On the contrary, it’s only one in a long line of poetic forms that predate many English forms of poetry. Japanese poetry forms, in particular, have always fascinated me not only for its brevity but for a different approach to content. While this isn’t a comprehensive text, this guide to Japanese poetry forms is a good place to start.

The earliest Japanese poetry has its roots in Chinese poetry and the Chinese language. While the earliest Japanese poems written in Chinese were called kanshi, the first Japanese poems written in Japanese were called waka. Waka are less a form than a broad term for classical Japanese poetry.

These classic Japanese poetry forms are still in use today, not only by Japanese poets, but poets around the world. In Victoria Chang’s recent book, OBIT , she largely used poems shaped like obituaries to mourn her parents. Interspersed in these mournful pages were small poems about her children, all of which were in the tanka form.

Of all the classic, waka poetry forms, tanka were the most popular. They were so popular, in fact, that poets started using them to communicate. One poet would write the first three lines, and then another poet would complete the six-line stanza. Six lines wasn’t enough to foster a conversation, however, and so the renga was born.

Renga use the tanka form of 5/7/5/7/7, but use that as a stanza. A renga must have at least 100 stanzas. Between the 12th and 15th centuries, renga were a favorite pastime not only of Japanese poets, but everyone in Japan from aristocrats on down. Renga were initially based on light, comic topics. As time went on and the form stayed popular, however, more serious renga were written. Thus a distinction between mushin (comic) and ushin (serious) renga was drawn.

Look again at the tanka or renga form. Pay close attention to those first three lines. Five syllables, seven syllable, five syllables. Sound familiar? Spinning out of the 100-stanza renga and six-line tanka was the most famous Japanese poetry form: haiku. Even at a fairly young age, I remember English teachers assigning the haiku form because of the small size and lack of rhyme. The form consists of three lines: five syllables, seven syllables, and five syllables. Only 17 total syllable. Simple, yes?

Well, maybe not so simple. Haiku generally focus on nature. With so few syllables available, every image needs to pack as much punch as possible. Rather than simply describing a pastoral setting, haiku seek to explore nature as a metaphor for emotion and the emotions evokes by nature.

One of the most famous haiku is by Matsuo Bashō, titled “The Old Pond,” which can be found in Basho: The Complete Haiku .

Despite its popularity, haiku is actually a newer Japanese poetry form. It started to be written in the 17th century, and the term haiku only came into use in the 19th century. Karai Senryu created a variation (the Senryu, named after him) that changed its focus from nature and emotion to human foibles and the irony of life. These variants are often far less serious and more satirical than their older cousin. Haiku was popularized in English in the early 20th century by the imagist poets such as Ezra Pound, H.D., and T.E. Hulme.

Haiga is not actually a form of poetry, but rather a different way of delivering that poetry. Japan, like China, has a storied history with calligraphy. Not only are the words important, but way in which these words are placed upon a page can be things of beauty and art.

As early as the 7th century in China and the 17th century in Japan, poems were laid over a painting using calligraphy. During Japan’s Edo period, the haiku and senryu forms became the chosen forms for this particular artistic treatment, and so the haiga was born. Haiga were frequently painted on wood blocks, cloth, or paper, and used as room decorations.

In Zen Buddhism, creating a haiga is one way of meditating, focusing on the words of the poem, the pastoral painted image, and the calligraphy all at once. In modern day, haiga seems to have found a twisted home with Instagram. Just search for poetry to find hundreds of images with stanzas floating in front of them. Okay, maybe that’s pushing the form too much.

Thank you for signing up! Keep an eye on your inbox. By signing up you agree to our terms of use