- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

- 30 May 2024

- Research & Ideas

Racial Bias Might Be Infecting Patient Portals. Can AI Help?

Doctors and patients turned to virtual communication when the pandemic made in-person appointments risky. But research by Ariel Stern and Mitchell Tang finds that providers' responses can vary depending on a patient's race. Could technology bring more equity to portals?

- 26 Apr 2024

Deion Sanders' Prime Lessons for Leading a Team to Victory

The former star athlete known for flash uses unglamorous command-and-control methods to get results as a college football coach. Business leaders can learn 10 key lessons from the way 'Coach Prime' builds a culture of respect and discipline without micromanaging, says Hise Gibson.

- 04 Mar 2024

Want to Make Diversity Stick? Break the Cycle of Sameness

Whether on judicial benches or in corporate boardrooms, white men are more likely to step into roles that other white men vacate, says research by Edward Chang. But when people from historically marginalized groups land those positions, workforce diversification tends to last. Chang offers three pieces of advice for leaders striving for diversity.

- 02 Jan 2024

- Cold Call Podcast

Should Businesses Take a Stand on Societal Issues?

Should businesses take a stand for or against particular societal issues? And how should leaders determine when and how to engage on these sensitive matters? Harvard Business School Senior Lecturer Hubert Joly, who led the electronics retailer Best Buy for almost a decade, discusses examples of corporate leaders who had to determine whether and how to engage with humanitarian crises, geopolitical conflict, racial justice, climate change, and more in the case, “Deciding When to Engage on Societal Issues.”

- 21 Nov 2023

Cold Call: Building a More Equitable Culture at Delta Air Lines

In December 2020 Delta Air Lines CEO Ed Bastian and his leadership team were reviewing the decision to join the OneTen coalition, where he and 36 other CEOs committed to recruiting, hiring, training, and advancing one million Black Americans over the next ten years into family-sustaining jobs. But, how do you ensure everyone has equal access to opportunity within an organization? Professor Linda Hill discusses Delta’s decision and its progress in embedding a culture of diversity, equity, and inclusion in her case, “OneTen at Delta Air Lines: Catalyzing Family-Sustaining Careers for Black Talent.”

- 31 Oct 2023

Beyond the 'Business Case' in DEI: 6 Steps Toward Meaningful Change

Diversity and inclusion efforts that focus on business outcomes alone rarely address root causes. Jamillah Bowman Williams, a visiting fellow at the Institute for the Study of Business in Global Society, offers tips for companies navigating their next stage of the DEI journey.

- 24 Oct 2023

When Tech Platforms Identify Black-Owned Businesses, White Customers Buy

Demand for Black-owned restaurants rises when they're easier to find on Yelp. Research by Michael Luca shows how companies can mobilize their own technology to advance racial equity.

- 16 Oct 2023

Advancing Black Talent: From the Flight Ramp to 'Family-Sustaining' Careers at Delta

By emphasizing skills and expanding professional development opportunities, the airline is making strides toward recruiting and advancing Black employees. Case studies by Linda Hill offer an inside look at how Delta CEO Ed Bastian is creating a more equitable company and a stronger talent pipeline.

.jpg)

- 10 Oct 2023

In Empowering Black Voters, Did a Landmark Law Stir White Angst?

The Voting Rights Act dramatically increased Black participation in US elections—until worried white Americans mobilized in response. Research by Marco Tabellini illustrates the power of a political backlash.

- 26 Sep 2023

Unpacking That Icky Feeling of 'Shopping' for Diverse Job Candidates

Many companies want to bring a wider variety of lived experiences to their workforces. However, research by Summer Jackson shows how hiring managers' fears of seeming transactional can ultimately undermine their diversity goals.

- 08 Aug 2023

Black Employees Not Only Earn Less, But Deal with Bad Bosses and Poor Conditions

More than 900,000 reviews highlight broad racial disparities in the American working experience. Beyond pay inequities, research by Letian Zhang shows how Black employees are less likely to work at companies known for positive cultures or work-life balance.

- 18 Jul 2023

Diversity and Inclusion at Mars Petcare: Translating Awareness into Action

In 2020, the Mars Petcare leadership team found themselves facing critically important inclusion and diversity issues. Unprecedented protests for racial justice in the U.S. and across the globe generated demand for substantive change, and Mars Petcare's 100,000 employees across six continents were ready for visible signs of progress. How should Mars’ leadership build on their existing diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts and effectively capitalize on the new energy for change? Harvard Business School associate professor Katherine Coffman is joined by Erica Coletta, Mars Petcare’s chief people officer, and Ibtehal Fathy, global inclusion and diversity officer at Mars Inc., to discuss the case, “Inclusion and Diversity at Mars Petcare.”

- 01 Jun 2023

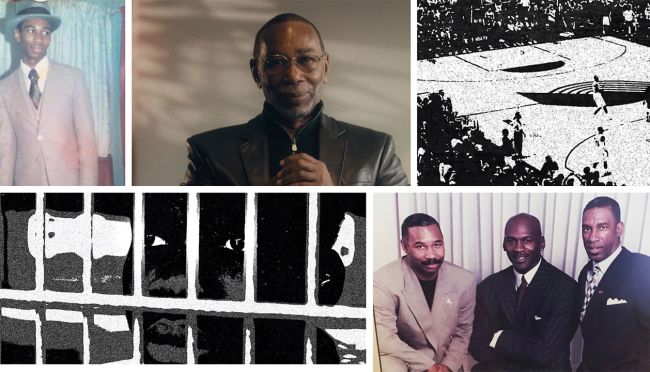

A Nike Executive Hid His Criminal Past to Turn His Life Around. What If He Didn't Have To?

Larry Miller committed murder as a teenager, but earned a college degree while serving time and set out to start a new life. Still, he had to conceal his record to get a job that would ultimately take him to the heights of sports marketing. A case study by Francesca Gino, Hise Gibson, and Frances Frei shows the barriers that formerly incarcerated Black men are up against and the potential talent they could bring to business.

- 31 May 2023

Why Business Leaders Need to Hear Larry Miller's Story

VIDEO: Nike executive Larry Miller concealed his criminal past to get a job. What if more companies were willing to hire people with blemishes on their records? Hise Gibson explores why business leaders should give the formerly incarcerated a second chance.

From Prison Cell to Nike’s C-Suite: The Journey of Larry Miller

VIDEO: Before leading one of the world’s largest brands, Nike executive Larry Miller served time in prison for murder. In this interview, Miller shares how education helped him escape a life of crime and why employers should give the formerly incarcerated a second chance. Inspired by a Harvard Business School case study.

- 08 May 2023

How Trump’s Anti-Immigrant Rhetoric Crushed Crowdfunding for Minority Entrepreneurs

When public anxiety about immigration surges, Black, Asian, and Hispanic inventors have a harder time raising funds for new ideas on Kickstarter, says research by William Kerr. What can platforms do to confront bias in entrepreneurial finance?

- 03 May 2023

Why Confronting Racism in AI 'Creates a Better Future for All of Us'

Rather than build on biased data and technology from the past, artificial intelligence has an opportunity to do better, says Business in Global Society Fellow Broderick Turner. He highlights three myths that prevent business leaders from breaking down racial inequality.

- 21 Feb 2023

What's Missing from the Racial Equity Dialogue?

Fellows visiting the Institute for the Study of Business in Global Society (BiGS) at Harvard Business School talk about how racism harms everyone and why it’s important to find new ways to support formerly incarcerated people.

- 31 Jan 2023

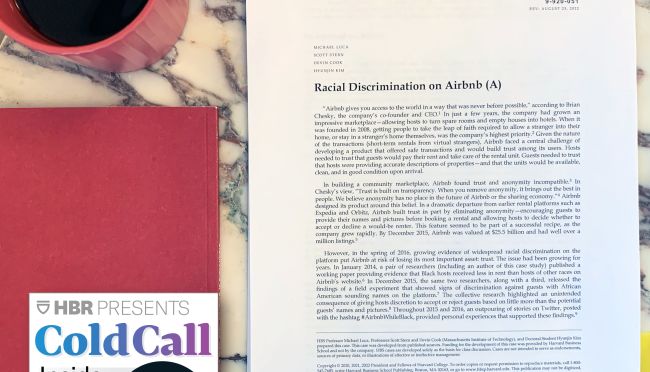

Addressing Racial Discrimination on Airbnb

For years, Airbnb gave hosts extensive discretion to accept or reject a guest after seeing little more than a name and a picture, believing that eliminating anonymity was the best way for the company to build trust. However, the apartment rental platform failed to track or account for the possibility that this could facilitate discrimination. After research published by Professor Michael Luca and others provided evidence that Black hosts received less in rent than hosts of other races and showed signs of discrimination against guests with African American sounding names, the company had to decide what to do. In the case, “Racial Discrimination on Airbnb,” Luca discusses his research and explores the implication for Airbnb and other platform companies. Should they change the design of the platform to reduce discrimination? And what’s the best way to measure the success of any changes?

- 03 Jan 2023

Confront Workplace Inequity in 2023: Dig Deep, Build Bridges, Take Collective Action

Power dynamics tied up with race and gender underlie almost every workplace interaction, says Tina Opie. In her book Shared Sisterhood, she offers three practical steps for dismantling workplace inequities that hold back innovation.

Accessibility tools

- Skip to main content

- Accessibility

You are here:

- Case studies

Main site sub navigation

In this section:

- The top level navigation links

- Legislation

- Leading Authorities

- Judicial review decisions

- Case notes - discrimination

- Case notes - human rights

- Reports on unresolved human rights complaints

- Tribunal exemptions

- Intervention guidelines

- Interventions

- Call for case studies

- Submissions

- Health equity

- Age case studies

- Breastfeeding case studies

- Family responsibilities case studies

- Gender identity case studies

- Impairment case studies

- Lawful sexual activity case studies

- Parental status case studies

- Political belief or activity case studies

- Pregnancy case studies

Race case studies

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander case studies

- Relationship status case studies

- Religious belief or religious activity case studies

- Sex discrimination case studies

- Sexuality case studies

- Trade union activity case studies

- Association case studies

- Sexual harassment case studies

- Unlawful requests for information case studies

- Victimisation case studies

- Vilification case studies

- Human rights case studies

- Guides and toolkits

- Fact sheets

- Human Rights Month 2019 Speaker Series: Right to education

- Human Rights Month 2019 Speaker Series: Understanding the impact of Queensland's Human Rights Act

- Working it Through

- A Human Rights Act for Queensland

- 2023 theme: Universal means everyone

- Events and training

- Human Rights Week in your workplace

- Posters and supporter resources

- Why the hummingbird?

- Queensland human rights timeline

The race case summaries are grouped into two categories: court and tribunal decisions, and conciliated outcomes.

- Race discrimination: summaries of court and tribunal decisions

- Race discrimination: summaries of conciliated outcomes

Court and tribunal decisions are made after all the evidence is heard, including details of loss and damage. The full text of court and tribunal decisions is available from:

- AustLII website

- Queensland Supreme Court Library website

Conciliated outcomes are where the parties have reached an agreement through conciliation at the Queensland Human Rights Commission.

Court and tribunal decisions

Respecting cultural practices.

Back to top

Language ability a characteristic of race

Comments to be taken in context, derogatory racial descriptions of workers, conciliated outcomes, demeaning racial comments ignored, racist comments and sexual harassment leads to resignation, different pay rate based on race, entertainment venue excluded asian customers, worker called offensive racist names, racial abuse and threats at work.

Studies find evidence of systemic racial discrimination across multiple domains in the United States

Harvard Pop Center faculty member Sara Bleich and her colleagues have published two studies examining experiences of racial discrimination in the United States.

One study found substantial black-white disparities in experiences of discrimination in the U.S. spanning multiple domains including health care, employment, and law enforcement, while a separate study found similar discrimination among Latinos in the United States. Given the connection between racial discrimination and poor health outcomes in both groups of Americans, the study calls for more interventions to address broad racial discrimination.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Who Discriminates in Hiring? A New Study Can Tell.

Applications seemingly from Black candidates got fewer replies than those evidently from white candidates. The method could point to specific companies.

By Eduardo Porter

Twenty years ago, Kalisha White performed an experiment. A Marquette University graduate who is Black, she suspected that her application for a job as executive team leader at a Target in Wisconsin was being ignored because of her race. So she sent in another one, with a name (Sarah Brucker) more likely to make the candidate appear white.

Though the fake résumé was not quite as accomplished as Ms. White’s, the alter ego scored an interview. Target ultimately paid over half a million dollars to settle a class-action lawsuit brought by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission on behalf of Ms. White and a handful of other Black job applicants.

Now a variation on her strategy could help expose racial discrimination in employment across the corporate landscape.

Economists at the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of Chicago this week unveiled a vast discrimination audit of some of the largest U.S. companies. Starting in late 2019, they sent 83,000 fake job applications for entry-level positions at 108 companies — most of them in the top 100 of the Fortune 500 list, and some of their subsidiaries.

Their insights can provide valuable evidence about violations of Black workers’ civil rights.

The researchers — Patrick Kline and Christopher Walters of Berkeley and Evan K. Rose of Chicago — are not ready to reveal the names of companies on their list. But they plan to, once they expose the data to more statistical tests. Labor lawyers, the E.E.O.C. and maybe the companies themselves could do a lot with this information. (Dr. Kline said they had briefed the U.S. Labor Department on the general findings.)

In the study, applicants’ characteristics — like age, sexual orientation, or work and school experience — varied at random. Names, however, were chosen purposefully to ensure applications came in pairs: one with a more distinctive white name — Jake or Molly, say — and the other with a similar background but a more distinctive Black name, like DeShawn or Imani.

What the researchers found would probably not surprise Ms. White: On average, applications from candidates with a “Black name” get fewer callbacks than similar applications bearing a “white name.”

This aligns with a paper published by two economists from the University of Chicago a couple of years after Ms. White’s tussle with Target: Respondents to help-wanted ads in Boston and Chicago had much better luck if their name was Emily or Greg than if it was Lakisha or Jamal. (Marianne Bertrand, one of the authors, testified as an expert witness in the trial over Ms. White’s discrimination claim.)

This experimental approach with paired applications, some economists argue, offers a closer representation of racial discrimination in the work force than studies that seek to relate employment and wage gaps to other characteristics — such as educational attainment and skill — and treat discrimination as a residual, or what’s left after other differences are accounted for.

The Berkeley and Chicago researchers found that discrimination isn’t uniform across the corporate landscape. Some companies discriminate little, responding similarly to applications by Molly and Latifa. Others show a measurable bias.

All told, for every 1,000 applications received, the researchers found, white candidates got about 250 responses, compared with about 230 for Black candidates. But among one-fifth of companies, the average gap grew to 50 callbacks. Even allowing that some patterns of discrimination could be random, rather than the result of racism, they concluded that 23 companies from their selection were “very likely to be engaged in systemic discrimination against Black applicants.”

There are 13 companies in automotive retailing and services in the Fortune 500 list. Five are among the 10 most discriminatory companies on the researchers’ list. Of the companies very likely to discriminate based on race, according to the findings, eight are federal contractors, which are bound by particularly stringent anti-discrimination rules and could lose their government contracts as a consequence.

“Discriminatory behavior is clustered in particular firms,” the researchers wrote. “The identity of many of these firms can be deduced with high confidence.”

The researchers also identified some overall patterns. For starters, discriminating companies tend to be less profitable, a finding consistent with the proposition by Gary Becker, who first studied discrimination in the workplace in the 1950s, that it is costly for firms to discriminate against productive workers.

The study found no strong link between discrimination and geography: Applications for jobs in the South fared no worse than anywhere else. Retailers and restaurants and bars discriminate more than average. And employers with more centralized personnel operations handling job applications tend to discriminate less, suggesting that uniform rules and procedures across a company can help reduce racial biases.

An early precedent for the paper published this week is a 1978 study that sent pairs of fake applications with similar qualifications but different photos, showing a white or a Black applicant. Interestingly, that study found some evidence of “reverse” discrimination against white applicants.

More fake-résumé studies have followed in recent years. One found that recent Black college graduates get fewer callbacks from potential employers than white candidates with identical resumes. Another found that prospective employers treat Black graduates from elite universities about the same as white graduates of less selective institutions.

One study reported that when employers in New York and New Jersey were barred from asking about job candidates’ criminal records , callbacks to Black candidates dropped significantly, relative to white job seekers, suggesting employers assumed Black candidates were more likely to have a record.

What makes the new research valuable is that it shows regulators, courts and labor lawyers how large-scale auditing of hiring practices offers a method to monitor and police bias. “Our findings demonstrate that it is possible to identify individual firms responsible for a substantial share of racial discrimination while maintaining a tight limit on the expected number of false positives encountered,” the researchers wrote.

Individual companies might even use the findings to reform their hiring practices.

Dr. Kline of Berkeley said Jenny R. Yang, a former chief commissioner of the E.E.O.C. and the current director of the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs, which has jurisdiction over federal contractors, had been apprised of the findings and had expressed interest in the researchers’ technique. (A representative of the agency declined to comment or to make Ms. Yang available.)

Similar tests have been performed since the 1980s to detect discrimination in housing by real estate agents and rental property owners. Tests in which white and nonwhite people inquire about the availability of housing suggest discrimination remains rampant.

Deploying this approach in the labor market has proved a bit tougher. Last year, the New York City Commission on Human Rights performed tests to detect employment discrimination — whether by race, gender, age or any other protected class — at 2,356 shops. Still, “employment is always harder than housing,” said Sapna Raj, deputy commissioner of the law enforcement bureau at the agency, which enforces anti-discrimination regulations.

“This could give us a deeper understanding,” Ms. Raj said of the study by the Berkeley and Chicago researchers. “What we would do is evaluate the information and look proactively at ways to address it.”

The commission, she noted, could not take action based on the kind of statistics in the new study on their own. “There are so many things you have to look at before you can determine that it is discrimination,” she argued. Still, she suggested, statistical analysis could alert her to which employers it makes sense to look at.

And that could ultimately convince corporations that discrimination is costly. “This is actionable evidence of illegal behavior by huge firms,” Dr. Walters of Berkeley said on Twitter in connection with the study’s release. “Modern statistical methods have the potential to help detect and redress civil rights violations.”

Eduardo Porter joined The Times in 2004 from The Wall Street Journal. He has reported about economics and other matters from Mexico City, Tokyo, London and São Paulo. More about Eduardo Porter

Explore Our Business Coverage

Dive deeper into the people, issues and trends shaping the world of business..

What Happened to Ad-Free TV?: Not long ago, streaming TV came with a promise: Sign up, and commercials will be a thing of the past. Here’s why ads are almost everywhere on streaming services now .

London Moves to Revive Its Reputation: As fears have grown that the city is losing its attractiveness for publicly traded businesses, Britain’s government is making changes to bring them back.

What Do Elite Students Want?: An increasing number of students desire “making a bag” (slang for a sack of money) as quickly as possible. Many of Harvard’s Generation Z say “sellout” is not an insult, appearing to be strikingly corporate-minded .

D.C.’s Empty Offices: Workers in Washington have returned to the office slowly , with a pervasive and pronounced effect on the local economy.

Trump’s Financial Future: Donald Trump has treated Trump Media, which runs his social network Truth Social, as a low-cost sideshow. Now a big portion of his wealth hinges on its success .

Race, ethnicity, and discrimination at work: a new analysis of legal protections and gaps in all 193 UN countries

Equality, Diversity and Inclusion

ISSN : 2040-7149

Article publication date: 1 February 2023

Issue publication date: 18 December 2023

While only one aspect of fulfilling equal rights, effectively addressing workplace discrimination is integral to creating economies, and countries, that allow for everyone's full and equal participation.

Design/methodology/approach

Labor, anti-discrimination, and other relevant pieces of legislation were identified through the International Labor Organization's NATLEX database, supplemented with legislation identified through country websites. For each country, two researchers independently coded legislation and answered questions about key policy features. Systematic quality checks and outlier verifications were conducted.

More than 1 in 5 countries do not explicitly prohibit racial discrimination in employment. 54 countries fail to prohibit unequal pay based on race. 107 countries prohibit racial and/or ethnic discrimination but do not explicitly require employers to take preventive measures against discrimination. The gaps are even larger with respect to multiple and intersectional discrimination. 112 countries fail to prohibit discrimination based on both migration status and race and/or ethnicity; 103 fail to do so for foreign national origin and race and/or ethnicity.

Practical implications

Both recent and decades-old international treaties and agreements require every country globally to uphold equal rights regardless of race. However, specific national legislation that operationalizes these commitments and prohibits discrimination in the workplace is essential to their impact. This research highlights progress and gaps that must be addressed.

Originality/value

This is the first study to measure legal protections against employment discrimination based on race and ethnicity in all 193 UN countries. This study also examines protection in all countries from discrimination on the basis of characteristics that have been used in a number of settings as a proxy for racial/ethnic discrimination and exclusion, including SES, migration status, and religion.

- Discrimination

- Migration status

Heymann, J. , Varvaro-Toney, S. , Raub, A. , Kabir, F. and Sprague, A. (2023), "Race, ethnicity, and discrimination at work: a new analysis of legal protections and gaps in all 193 UN countries", Equality, Diversity and Inclusion , Vol. 42 No. 9, pp. 16-34. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-01-2022-0027

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2023, Jody Heymann, Sheleana Varvaro-Toney, Amy Raub, Firooz Kabir and Aleta Sprague

Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

Introduction

Work plays a fundamental role in shaping the conditions of people's lives. Earnings from employment are the predominant source of income for most people; income in turn shapes access to a wide range of necessities including housing, transportation, and food, as well as non-essentials that impact quality of life and access to opportunities. In many countries where health insurance is partial or incomplete, work shapes access to healthcare. And by affecting where families live and whether caregivers can take time off to meet the developmental needs of children, the availability and conditions of work can have profound impacts on child development and education. Likewise, as adults age, as well as at the end of life, work histories can and do shape retirement income in most countries, and working conditions influence the ability of adults to care for aging family members.

As a result, when discrimination impedes work opportunities or results in loss of income, the consequences affect not only the quality and equality of work lives, but also of many other spheres of life. Moreover, when certain groups of workers routinely face bias in the workplace, this discrimination widens other inequalities in the economy, with ripple effects that have impacts on health, housing, children's access to quality education, and equal rights more broadly.

Given these vast and intergenerational impacts, the extent and persistence of workplace discrimination on the basis of race and ethnicity worldwide—which occurs at each stage of employment, including hiring, promotions, demotions, pay, working conditions, and terminations—represents a significant threat to both individual households and societies as a whole, as well as a clear violation of fundamental human rights. Moreover, studies in countries around the world have documented how employment discrimination on the basis of race/ethnicity commonly intersects with discrimination based on migration status, socioeconomic status, gender, and other characteristics, compounding other forms of inequality. While only one aspect of fulfilling equal rights, effectively addressing workplace discrimination is integral to creating economies, and countries, that allow for everyone's full and equal participation.

In this article, we review the research evidence on employment discrimination based on race and on the impact of anti-discrimination legislation, and then present the methods and results of the first study of anti-discrimination protections in all 193 UN countries.

Discrimination in hiring

A wide range of studies have demonstrated racial and ethnic discrimination in hiring, including studies in which researchers submit fictitious CVs and applications that reflect similar credentials and experience, but that vary with respect to photos, names, and/or experiences suggestive of different racial or ethnic identities. These “correspondence studies,” which improved on prior methods of testing for racial discrimination by making candidates substantively identical except for markers of race/ethnicity ( Bertrand and Duflo, 2017 ), find that presumed race/ethnicity influences the likelihood that a particular candidate receives an invitation to interview, with those representing historically marginalized racial or ethnic groups consistently receiving fewer callbacks ( Baert, 2018 ).

Other research approaches include direct interviews with hiring managers and simulations in which study participants rate the strength of hypothetical job candidates based on their photos and descriptions of their experience and characteristics where, again, the principal aspect varied is race/ethnicity, either on its own or together with intersectional characteristics like migration status or gender.

These research approaches also document the persistence of discrimination in hiring across jobs and geographies. For example, research in Nigeria found that managers of both public and private organizations were more likely to hire applicants from their own ethnic group ( Adisa et al. , 2017 ). A study spanning five European countries—Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, and the United Kingdom—demonstrated discrimination in the hiring of Black and Middle Eastern men ( Di Stasio and Larsen, 2020 ).

Discrimination based on common proxies for race or ethnicity can likewise shape job prospects. In Canada, for example, migrants from sub-Saharan Africa report that their accents can be a barrier to becoming employed and having career mobility ( Creese, 2010 ), while in the US, numerous court cases have illustrated how Black women commonly face barriers to employment because their natural hairstyles are found to violate “neutral” grooming codes ( Greene, 2017 ).

Discrimination is also often intersectional. In Germany, a 2020 study found that women with Turkish names were less likely than those with German names to receive interview invitations, and this gap widened further for women wearing headscarves ( Weichselbaumer, 2020 ). Similarly, in a Mexico study, both marital status and skin color affected women's chance of receiving an interview ( Arceo-Gomez and Campos-Vasquez, 2014 ). In Belgium, women from minority ethnic groups were less likely to be considered for a “high-cognitive demanding job” than either native women or minority ethnic men ( Derous and Pepermans, 2019 ).

Discrimination in promotions

Studies have also documented racial and ethnic discrimination in promotions across professions, from police forces to law firms to universities ( Tomlinson, 2019 ; Zempi, 2020 ). From Finland to South Africa to the United Kingdom and the United States, workers from marginalized racial and ethnic groups report discrimination in promotion, consistent with the research evidence based on multilevel multivariate studies of discrimination, as well as based on implicit bias testing of supervisors ( Hatch et al. , 2016 ; Mayiya et al. , 2019 ; Stalker, 1994 ; Yu, 2020 ; Zempi, 2020 ). In Canada, research has documented that visible minorities have less upward mobility even after controlling for education, work experience, time with the employer, and other factors ( Javdani, 2020 ), including both supply- and demand-side factors ( Javdani and McGee, 2018 ; Yap, 2010 ; Yap and Konrad, 2009 ).

Aside from direct discrimination in promotions, employer practices that evaluate employee conduct differently or otherwise deny opportunities for professional advancement based on race or ethnicity can affect opportunities within the workplace. For example, a study that experimentally changed the race/ethnicity of an employee in a photo while asking study participants to evaluate their performance demonstrated that simple acts such as being late for work led to a significantly greater negative impact on the appraisal of hypothetical employees when the photo showed a Black or Latinx employee than when the photo showed a white employee ( Luksyte et al. , 2013 ). Visible minorities are also less likely to receive training opportunities that can influence upward mobility in the labor force ( Dostie and Javdani, 2020 ).

Discrimination in terminations

Both direct discrimination by employers and structural discrimination that cuts across economies can make workers from marginalized racial and ethnic groups more vulnerable to terminations. For example, studies have found that during economic downturns, immigrants and workers from historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups face heightened risks of labor market discrimination and job loss ( Couch and Fairlie, 2010 ; Lessem and Nakajima, 2019 ). Moreover, the consequences of past discrimination and exclusion from economic opportunities mean that workers from underrepresented groups are less likely to have seniority within a given organization or company. As a result, in addition to direct racial/ethnic discrimination that may lead to higher rates of termination, “last hired, first fired” policies can result in indirect discrimination against workers from historically excluded groups.

Impacts of discrimination in hiring, job positions, and promotions on pay inequality

Discrimination in hiring can impact initial salaries and level and type of starting position. When individuals are hired into jobs below their skill level because of bias based on race and ethnicity, they earn less than they would have earned had there been no discrimination ( Coleman, 2003 ). Likewise, when discrimination results in the overrepresentation of workers from historically marginalized racial/ethnic groups in limited employment capacities, including temporary or seasonal jobs, gaps in both pay and benefits further widen. Survey research across 30 European countries showed that even after controlling for education, experience, occupation, and other categories, racial and ethnic minorities were more likely to end up in jobs where their skills were underutilized, leading to lower wages than if they were in a position more matched to their skills and offering reduced pathways for advancement ( Rafferty, 2020 ). In Chile, qualitative research has found that Peruvian migrants simultaneously experience limited employment trajectory due to their external migrant status alongside racialization by local Chileans who perceive them to be more fit for low-status and low-income positions due to assumptions about their physical and cultural traits ( Mora and Undurraga, 2013 ).

Direct pay discrimination

Even for the same job position, the “unexplained” wage differential after taking experience into account gives an indication of the amount of the wage differential that could be due to discrimination and bias. One-half to two-thirds of wage differences across racial and ethnic groups in some studies have been estimated to be due to bias ( Drydakis, 2012 ; Piazzalunga, 2015 ). While the data clearly demonstrates the existence of bias and discrimination in pay against specific groups in a range of countries, there has not been a comprehensive look across countries and racial/ethnic groups to document in detail when and where the wage gaps are greatest and lowest, before and after taking into account the impact of bias throughout the work lifecourse.

The documented and potential impacts of national laws addressing discrimination

Individual countries that have passed antidiscrimination laws have seen improvements including greater equality in hiring and lowering of wage disparities ( Leck et al. , 1995 ). While antidiscrimination laws alone do not eliminate discrimination in hiring, pay, promotions, or terminations, studies both across countries and across populations have demonstrated that antidiscrimination laws can make a difference. In Canada, for example, studies of the Employment Equity Act found that the share of visible minorities who were employed in the private sector increased to much closer to the percentage of the population following the law's adoption ( Agocs, 2002 ; Leck and Saunders, 1992 ). In the United States, studies have found that antidiscrimination laws contributed to wage and income increases for Black workers ( Collins, 2003 ; Donohue and Heckman, 1991 ) and a narrowing of the racial/ethnic pay gap ( Chay, 1998 ).

These findings on laws' impacts on employment outcomes by race parallel those observed for other groups of marginalized workers. For example, one study of 141 countries found that laws prohibiting gender discrimination in employment increased women's labor force participation in formal jobs ( del Mar Alonso-Almeida, 2014 ), while in the UK, legislation guaranteeing equal pay and non-discrimination in employment on the basis of sex resulted in a 19.4% increase in women's earnings and a 17% increase in women's employment rates relative to men's ( Zabalza and Zafiris, 1985 ). Moreover, explicitly prohibiting all forms of workplace discrimination matters to norms. In addition to their practical or applied value, laws prohibiting discrimination have important expressive value that can shape workplace expectations as well as societal views of equality more broadly, with the potential to affect rates of both explicit and implicit bias ( Sunstein, 1996 ). At the same time, the past several decades of antidiscrimination law have revealed important gaps to address. First, as many of the studies cited in the previous section illustrated, racial and ethnic discrimination commonly co-occurs with discrimination based on migration status, foreign national origin, social class, and other characteristics, highlighting the cumulative and often intersectional impacts of key facets of identity on work-related experiences around the world. Clearly banning all common grounds of discrimination, including those used as proxies for race or ethnicity or that commonly intersect with race or ethnicity, is a critical first step.

Second, prohibitions of indirect discrimination can offer important protection against racial/ethnic discrimination, including in instances where discrimination based on an unprotected ground has disparate impacts on the basis of race or ethnicity. This is true both for common grounds of discrimination that would ideally be explicitly covered by domestic labor laws (as they are by international treaties, e.g. national origin) ( Demetriou, 2016 ), as well as proxies for racial/ethnic discrimination that are not generally addressed on their own (e.g. accents and hairstyles) ( Justesen, 2016 ). In contrast, when discrimination laws take an overly formal approach to discrimination that only covers acts that were direct or intentional, they fail to account for the extensive evidence demonstrating that policies and practices that are racially neutral on their face may have disproportionate consequences for workers from historically marginalized groups.

Third and finally, while protections against employment discrimination are essential, more attention must be paid to implementation. While a range of actions are needed, evidence shows that having legal protections in place against retaliation may increase reporting rates by reassuring workers that their careers will be protected if they report discrimination ( Bergman et al. , 2002 ; Gorod, 2007 ; Keenan, 1990 ; Pillay et al. , 2018 ).

This is the first study to examine legislation in all 193 UN countries to map the extent to which each country in the world has protections against racial and ethnic discrimination in hiring, promotions, training, demotions, and terminations, as well as whether they proactively support implementation through clear legislative prohibitions of retaliation for reporting. Further, we examine to what extent countries not only address direct discrimination based on race/ethnicity, but also indirect racial/ethnic discrimination and/or direct discrimination based on grounds that can serve as proxies depending on the historical and societal context for racial discrimination, including religion, migration status, and socioeconomic status. Further, we highlight examples where countries explicitly address intersectionality. Finally, we examine whether there were gains over the past five years in the number of countries that are prohibiting each type of discrimination.

Methodology

Data source.

We constructed a database of prohibitions against discrimination in private sector labor in all 193 UN member states as of January 2021. Labor, anti-discrimination, and other relevant pieces of legislation were identified through the International Labor Organization's NATLEX database, supplemented with legislation identified through country websites. A coding framework was developed to systematically capture key policy features. This coding framework was reviewed by researchers, lawyers, and other leaders working on employment discrimination and tested on a subset of countries before database coding commenced.

For each country and protected characteristic studied, two researchers independently read legislation in its original language or a translation and used the coding framework to assess whether legislation specifically prohibited discrimination in each aspect of work or broadly, whether there were any exceptions to prohibitions of discrimination based on employer characteristics, and whether there were specific provisions in place to support effective implementation. In countries where anti-discrimination protections are legislated subnationally, the lowest level of protection across states or provinces was captured. Answers were then reconciled to minimize human error. When the two researchers could not arrive at an agreement based on the codebook framework, the full coding team met to discuss, and the coding framework was updated to reflect the decision. When updates were made, countries that had already been coded were checked for consistency with the update.

Once coding was complete, systematic quality checks were conducted of variables that proved challenging for researchers during the coding process. Randomized quality checks were conducted of variables that were more straightforward, checking first twenty countries to ensure no errors were identified and a larger subset of countries if there were errors. Finally, outlier verifications globally and by region or country income level were conducted for all variables. In order to assess whether legislative provisions have strengthened over time, similar methods were used to construct measures of laws in place as of August 2016.

Strength of prohibitions of discrimination

We examined legislation across six areas: hiring, pay, training, promotions and/or demotions, termination, and harassment. For each area, we assessed the strength of protection against racial and ethnic discrimination. We classified countries as having a “specific prohibition of racial or ethnic discrimination” if legislation either: 1) explicitly addressed racial and ethnic discrimination in that aspect of work (“racial discrimination in hiring is prohibited”); or 2) broadly prohibited racial discrimination at work (“there shall be no discrimination at work based on race”) and guaranteed equality in the specific area (“no one shall be discriminated against in hiring decisions”). For equal pay, we further distinguished between countries that guaranteed equal pay for equal work and those that had a stronger provision guaranteeing equal pay for work of equal value which would prohibit differences in pay when there is occupational segregation.

Countries were classified as having a “broad prohibition of racial or ethnic discrimination” if legislation broadly prohibited discrimination based on race or ethnicity, but did not address specific aspects of work. Countries were coded as having a “general prohibition of discrimination” if legislation did not explicitly address race or ethnicity but banned discrimination in an aspect of work for all workers. “No explicit prohibition” denotes when legislation did not take any of the approaches above. We separately analyzed whether prohibitions of discrimination included indirect discrimination, which would protect against seemingly neutral practices or criteria that have disparate impacts across race and/or ethnicity.

Intersecting characteristics

In many countries racial and/or ethnic discrimination is deeply intertwined with other characteristics, including social class, migration status, foreign national origin, and religion. Accordingly, we assessed whether laws prohibit discrimination based on both race and/or ethnicity and these intersecting characteristics.

Employer responsibilities

We assessed whether legislation required employers to take measures to prevent racial or ethnic discrimination in the workplace. In doing so, we distinguished between legislation that made it a general responsibility and legislation that outlined specific steps for employers to take. These specific prevention steps included requirements to create a code of conduct to prevent racial discrimination, establish disciplinary procedures, raise awareness of anti-discrimination laws, or conduct trainings to prevent discrimination.

Prohibitions of retaliation

To capture the extent to which provisions effectively covered the range of forms that retaliation can take, we coded the protections for individuals who reported discrimination, filed a complaint, or initiated litigation (any adverse action, disciplinary action, or retaliatory dismissal only) and whether prohibitions of retaliation covered all workers participating in the investigation.

Firm-based exceptions

In some countries, prohibitions of discrimination are weakened by provisions that exempt certain employers. We captured exceptions that broadly applied to prohibitions of discrimination or specifically in different aspects of work based on firm type for small businesses, charities and non-profits, and religious organizations.

All analyses were conducted using Stata MP 14.2. Differences were assessed by region using the Pearson's chi-square statistics. Region was categorized according to the World Bank's country and lending groups as of 2020 [ 1 ].

Globally, 153 countries prohibited at least some form of racial and/or ethnic discrimination at work in 2021, a modest increase from 148 countries in 2016 ( Figure 1 ). Three of the countries introducing these new prohibitions were in Sub-Saharan Africa (Mali, South Sudan, and Zambia), one in Europe (Iceland), and one in the South Pacific (Tuvalu). An additional five countries expanded existing prohibitions of racial and/or ethnic discrimination either to broadly prohibit discrimination at work in addition to specific prohibitions in certain areas (Barbados and Honduras) or to comprehensively cover discrimination at work in all areas, as well as indirect racial and/or ethnic discrimination (Andorra, Burundi, and Sao Tome and Principe).

Gaps in prohibitions are found in every region of the world. Countries in the Americas were the most likely to prohibit at least some form of racial discrimination at work, followed closely by Europe and Central Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. In each of these regions, only ten percent or fewer of countries lacked at least some form of prohibition. In contrast, a majority of countries lack prohibitions of racial discrimination in East Asia and Pacific and South Asia ( Figure 2 ). Differences were statistically significant between these two regions and the three regions with the highest levels of prohibitions ( p < 0.01).

In 2016, 107 countries had a law that explicitly prohibited race-based discrimination in hiring. That number increased to 115 countries in 2021 (see Figure 2 ). An additional 27 countries in 2016 and 29 countries in 2021 had either a broad prohibition of race discrimination or a general prohibition of discrimination in hiring. Prohibitions of racial/ethnic discrimination in hiring were most common in Europe and Central Asia (91%) followed by sub-Saharan Africa (62%). In all other regions, fewer than half of countries prohibited racial discrimination in hiring ( Figure 3 ).

Training and promotions/demotions

Eighty countries in 2016 and 88 countries in 2021 prohibited discrimination based on race in training. Eighty-three countries in 2016 prohibited discrimination in promotions and demotions. In 2021, this number increased to 90 countries.

While less than three-quarters of countries prohibited racial discrimination in training in Europe and Central Asia (74%), these prohibitions were still more common than in every other region. Similar trends were found for promotions and/or demotions.

The number of countries guaranteeing equal pay for work of equal value, increased from 34 in 2016 to 41 in 2021. Overall, including guarantees both of equal pay for work of equal value and equal pay for equal work, 91 countries in 2016 and 96 countries in 2021 guaranteed equal pay across racial and ethnic groups. More countries in Europe and Central Asia (77%) prohibited racial discrimination in pay than those in sub-Saharan Africa (56%), the Middle East and North Africa (27%), and South Asia (27%).

Terminations

In 2016, 106 countries prohibited racial discrimination in terminating employment. That number increased to 112 countries in 2021. Prohibitions of racial/ethnic discrimination in terminations were most common in Europe and Central Asia (74%), Sub-Saharan Africa (71%), and the Americas (60%). In contrast, less than a third of countries prohibited racial discrimination in terminations in East Asia and Pacific (30%) and South Asia (25%).

Only 66 countries explicitly prohibited workplace harassment based on race/ethnicity in 2016. By 2021, that number had increased to 72. Only a minority of countries prohibited racial and/or ethnic harassment in all regions except Europe and Central Asia.

Indirect discrimination

Sixty-three countries prohibited indirect discrimination based on race and/or ethnicity in 2016, increasing to 71 countries in 2021. Only a third of countries in sub-Saharan Africa, a fifth of those in East Asia and Pacific and the Americas, and an eighth of those in South Asia explicitly addressed indirect racial/ethnic discrimination. No countries in the Middle East and North Africa did so.

Intertwined, multiple and intersectional discrimination

Prohibitions of discrimination based on both race and/or ethnicity and religion were widespread: 151 countries prohibited at least some aspect of workplace discrimination based on both characteristics in 2021. However, only 117 countries prohibited at least some aspect of workplace discrimination based on both race and/or ethnicity and social class. Even fewer prohibited discrimination based on both race and/or ethnicity and foreign national origin (90 countries) or migration status (81 countries).

Countries in sub-Saharan Africa were most likely to prohibit discrimination based on race and social class, as well as discrimination based on race and foreign national origin. While prohibitions of racial discrimination and religion, social class, or foreign national origin were comparatively high in the Americas, prohibitions of discrimination based on migration status were markedly lower. While nearly two-thirds of countries in Europe and Central Asia addressed migration status alongside race, only half prohibited discrimination based on foreign national origin ( Figure 4 ).

Finally, a minority of countries explicitly addressed the concepts of intersectionality or multiple discrimination in their discrimination legislation. Kenya's National Gender and Equality Commission Act recognizes intersectionality in defining marginalized groups to be people “disadvantaged by discrimination on one or more of the grounds in Article 27(4) of the Constitution” which includes “race, sex, pregnancy, marital status, health status, ethnic or social origin, colour, age, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, dress, language or birth” ( 2012 ). Australia's Racial Discrimination Act prohibits “acts done for 2 or more reasons” where “one of the reasons is the race, colour, descent or national or ethnic origin of a person” ( 1975 ). In Macedonia, the Law on Prevention of and Protection Against Discrimination defines multiple discrimination to be a severe form of discrimination ( 2010 ).

Only a smaller minority of countries (38) took the additional step of requiring employers to take one or more specific measures to prevent racial discrimination. An additional 8 countries had general language requiring employers to take preventative steps, without specifying what those steps would look like.

Protections in the event of discrimination

In the event that discrimination occurred and employees filed a report or initiated litigation, a modest majority of countries took the important step of prohibiting retaliation against the employee who filed the complaint. Seventy-eight countries prohibited employers from retaliating in any way, an additional 7 prohibited harassment or any disciplinary action, and 26 only prohibited dismissing the employee ( Table 1 ). A similar number of countries (76) protected employees who participated in investigations from being retaliated against.

Are any employers exempt?

When countries had laws in place prohibiting discrimination, they overwhelmingly applied to all employers. In rare cases small businesses were exempt, including in 5 countries in the case of hiring, 4 countries in the case of training and terminations, and 3 countries in the case of pay and promotions and demotions ( Table 2 ). Charities and nonprofits had similarly uncommon exemptions. The group that was most frequently exempted from these prohibitions of racial discrimination were religious organizations. Fourteen countries exempted religious organizations from bans on discriminations based on race in hiring, training, and terminations, 13 exempted religious organizations in terms of racial discrimination in promotions and demotions, and 9 in the case of pay.

Around the world there has been an explosion of demonstrations and attention to the critical issue of racial discrimination over the past two years, building on the many decades of activism urging action on racial injustices that came before. And while catalyzed by state violence, these recent demonstrations also clearly took aim at the deeply entrenched economic disparities across race that persist across countries, which were on full display as workers from marginalized racial and ethnic groups lost jobs in historic numbers two months into the pandemic.

In response, governments and companies worldwide pledged action. Ensuring that discrimination is clearly prohibited in every country is an essential first step both for changing norms and attitudes and for giving people who are discriminated against more tools to combat the discrimination. Modest progress has been made over the past five years in increasing guarantees of equality, regardless of race and ethnicity, around the world. Between 2016 and 2021, the number of countries legally prohibiting racial and ethnic discrimination in the workplace increased and the strength of provisions improved. Eight more countries prohibited discrimination in hiring and 6 more in terminations. Seven more countries guaranteed equal pay for work of equal value based on race. Moreover, 8 more countries prohibited indirect discrimination based on race and ethnicity.

Yet unconscionable gaps remain. More than 1 in 5 countries have no prohibition of workplace discrimination based on race. Moreover, more than 1 in 4 countries, 54 in total, have no prohibition against racial discrimination in pay. Furthermore, more than a dozen countries provide for exceptions to the prohibition of racial discrimination for religious organizations.

Many countries also fail to offer adequate legal protection against both direct racial discrimination and other forms of discrimination that often occur simultaneously, have disparate impacts on the basis of race, and/or serve as proxies for racial discrimination. For example, in many countries around the world, marginalized racial and ethnic groups are also disproportionately poor due to historic and ongoing economic exclusion. In settings where racial and ethnic discrimination is prohibited but social class-based discrimination remains allowed, class-based discrimination can be used to practically discriminate based on race and ethnicity, particularly if indirect discrimination is likewise unaddressed in the law. Yet 76 countries fail to prohibit discrimination based on both social class and race and/or ethnicity; 121 lack protections against indirect discrimination; and 58 countries lack either protection.

Similarly, while discrimination based both on race/ethnicity and migration status is pervasive, many countries lack comprehensive protections addressing these and related grounds. The evidence illustrating why stronger laws are needed is compelling. For example, a study on labor force participation in Western Europe found that migrants from sub-Saharan Africa, North Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia earned over 20% less income than Western European internal migrants. Compared to internal Western European migrants, external migrants from MENA and sub-Saharan Africa regions were also less likely to be employed and part of the labor force in Europe ( Kislev, 2017 ). National laws that formally and explicitly prohibit multiple forms of discrimination may help protect more individuals and reduce inequalities in employment opportunities. Yet, 112 countries fail to prohibit discrimination based on both migration status and race and/or ethnicity and 103 fail to do so for foreign national origin and race and/or ethnicity.

Finally, even when legal protections are in place, it is crucial that there are both prevention and enforcement mechanisms. 107 countries prohibited racial and ethnic discrimination but did not place any explicit requirements on employers to try to prevent discrimination. Only 38 countries required employers to take specific steps and only an additional 8 required employers generally to work towards prevention.

The critical need to accelerate progress

The significant overall gaps in protections, alongside the findings that the expansion over the past five years of laws prohibiting racial discrimination at work has been slow, underscores the need to accelerate the pace of change on legal reforms—as a matter of human rights, an important determinant of individual and household incomes, and a prerequisite for countries to reach their full potential. Ensuring equal opportunities in employment on the basis of race and ethnicity has vast implications for individuals, families, and their broader communities. A significant body of literature has documented how access to employment, job quality, and adequate income shape mental and physical health, overall life satisfaction, and the ability to meet material needs ( Calvo et al ., 2015 ; Murphy and Athansou, 1999 ). When work opportunities are unevenly distributed by race due to both individual and structural discrimination, these disparities drive broader inequalities.

Moreover, all countries have agreed to do so. The Sustainable Development Goals, adopted by all UN member states in 2015, commit governments to “empower and promote the social, economic and political inclusion of all, irrespective of age, sex, disability, race, ethnicity, origin, religion or economic or other status” and “[e]nsure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome, including by eliminating discriminatory laws, policies and practices and promoting appropriate legislation, policies and action in this regard” ( United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2015 ). By adopting the SDGs, countries worldwide agreed to realize these commitments by 2030. To meet that timeline, accelerating the pace of change on fundamental anti-discrimination protections is essential.

This builds on a long history of international agreements guaranteeing equal rights regardless of race or ethnicity, including in the field of employment. Many of these have been in place for decades. Foremost among them is the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination ( United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, 1965 ), which has been ratified by 182 countries ( United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2021c ), declares that States Parties have a duty to “prohibit and to eliminate racial discrimination in all its forms and to guarantee the right of everyone, without distinction as to race, colour, or national or ethnic origin, to equality before the law, notably in the enjoyment of (…) The rights to work, to free choice of employment, to just and favourable conditions of work, to protection against unemployment, to equal pay for equal work, to just and favourable remuneration” ( United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, 1965 ).

In fact, nearly every major global human rights agreement commits countries to treating all people equally regardless of race or ethnicity. These include, among others, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted as the first global agreement of the United Nations and considered binding on all countries ( United Nations General Assembly, 1948 ), the International Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural Rights, a binding treaty ratified by 171 countries ( United Nations General Assembly, 1966 ; United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2021b ), and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, ratified by 173 countries ( United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, 1966 , 2021a ).

Finally, beyond its importance to individuals, families, and communities and deep intrinsic value as a matter of human rights, ending racial discrimination in the labor market has significant implications for economies and companies. For example, in the US alone, estimates from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco find that closing the racial gaps in employment-to-population ratios between 1990 and 2019 would have boosted 2019 GDP by over $150 billion ( Buckman et al. , 2021 ), while other research has forecast that closing the racial earnings gap by 2050 would boost GDP by 22% ( Turner, 2018 ). Likewise, a significant body of evidence demonstrates that greater racial and ethnic diversity within companies, including on boards, improves their financial performance and degree of innovation ( Erhardt et al. , 2003 ; Herring, 2009 ; Cheong and Sinnakkannu, 2014 ; Thomas et al. , 2016 ; Hunt et al. , 2018 ). For example, a study of 492 firms found a strong relationship between ethnic and linguistic diversity and total revenue, dividends, sales and productivity ( Churchill, 2019 ). Particularly as more companies work and hire trans-nationally, the extent to which laws in all countries prohibit racial and ethnic discrimination at work matters to overall performance.

Research limitations and the need for a broader research agenda on policies and outcomes

While this study provides an important first look at prohibitions against racial and ethnic discrimination at work in all the world's countries, it has important limitations. This study did not quantify laws related to intersectional discrimination, including, among others, gender, age, disability, sexual orientation, and gender identity. Yet as past scholarship and case law have shown, addressing each individual basis for discrimination still may not be enough to reach the unique forms of discrimination that arise when multiple grounds of discrimination intersect, particularly if workers are required to prove each of their discrimination claims discretely and sequentially. Explicit protections against intersectional discrimination, and judiciaries willing and trained to apply them, may be needed ( Crenshaw, 1989 ; Fredman, 2016 ).

Future research should also examine prohibitions of discrimination in working conditions, given the evidence of inequalities. For example, research has shown that non-Hispanic Black workers and foreign-born Hispanic workers are disproportionately hired into jobs with the higher injury risk and increased prevalence of work-related disability ( Seabury et al. , 2017 ). Another study on COVID-19 job exposures found that Latinx and Black frontline workers were overrepresented in lower status occupations associated with higher risk and less adequate COVID-19 protections, contributing to the higher prevalence of infection in these populations ( Goldman et al. , 2021 ).

Further, we need to measure laws that reduce bias in informal as well as formal mechanisms that play a large role in the recruitment, hiring, and promotion processes, as well as in determining working conditions. Evidence has shown social networks and informal relationships can not only impact recruitment, but also can contribute to inequities in salary negotiations and mentorship at the hiring stage ( Seidel et al. , 2000 ; Spafford et al. , 2006 ).

These expansions on the law and policy data presented here should be part of a broader research agenda on racial equity in the global labor market that examines not only which laws and policies are in place but what impacts they are having. As with other policy areas, developing longitudinal quantitative, globally comparative measures of anti-discrimination laws helps make it possible for researchers to rigorously analyze the relationship between policy change and outcomes, producing actionable evidence about “what works” across countries ( Raub et al. , 2022 ). However, even with the new policy data we have developed, improvements in outcomes data will be essential to measure the impact globally of advances and legal gaps. Globally comparative data on experiences of racial discrimination across countries which is essential for measuring the impact of legal change globally has been limited to date for several reasons including the wide range across countries of who suffers racial and ethnic discrimination and the variability of country willingness to collect data.

Addressing discrimination: a global responsibility

While the workplace is only one location where racial and ethnic discrimination occurs, it is a crucial one. Ensuring equal opportunity to be hired and equal treatment in pay, working conditions, and promotions together influences whether individuals can lead full work lives, contribute to household income, and not only meet basic needs but also invest in the future of their families and communities. Moreover, global agreements have committed countries around the world to combatting discrimination based on race and ethnicity, including in the specific context of employment.

For these international instruments to have full impact, however, specific country-level legislation that operationalizes their commitments and prohibits discrimination in the workplace is essential. To accelerate progress toward ending racial and ethnic discrimination in employment worldwide—a basic human right—we need to monitor the steps countries are taking to address and eliminate discrimination in all aspects of work, including hiring, promotion, pay, and terminations. While legal guarantees are not enough—and norm change, leadership, and social movements are likewise critical to successfully eliminating discrimination both at work and more broadly—clear stipulations that companies are not allowed to discriminate are essential, as are strong and regularly updated accountability mechanisms.

Do countries prohibit racial and/or ethnic discrimination in all aspects of work?

Number of countries prohibiting racial and/or ethnic discrimination at work by aspect of work and year

Percentage of countries prohibiting racial and/or ethnic discrimination at work by region and aspect of work

Number of countries prohibiting at least some discrimination at work based on race and/or ethnicity and intersecting characteristics by region

Countries with prohibitions of retaliation against those reporting discrimination

Countries with exceptions to prohibitions of racial and/or ethnic discrimination

The World Bank's (WB) regional classifications can be found here: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups . While Malta is classified as part of the Middle East and North Africa by the WB, it is also a member of the European Union (EU) and therefore more likely to have legislation reflecting the EU's principles and directives. Thus, we classified Malta as a part of Europe and Central Asia. All other countries retained their WB classifications.

Adisa , T.A. , Osabutey , E.L.C. , Gbadamosi , G. and Mordi , C. ( 2017 ), “ The challenges of employee resourcing: the perceptions of managers in Nigeria ”, The Career Development International , Vol. 22 No. 6 , pp. 703 - 723 .

Agocs , C. ( 2002 ), “ Canada's employment equity legislation and policy, 1987-2000: the gap between policy and practice ”, International Journal of Manpower , Vol. 23 No. 3 , pp. 256 - 276 .

Arceo-Gomez , E. and Campos-Vazquez , R. ( 2014 ), “ Race and marriage in the labor market: a discrimination correspondence study in a developing country ”, American Economic Review , Vol. 104 No. 5 , pp. 376 - 380 .

Baert , S. ( 2018 ), “ Hiring discrimination: an overview of (almost) all correspondence experiments since 2005 ”, Audit Studies: Behind the Scenes with Theory, Method, and Nuance , pp. 63 - 77 .

Bergman , M.E. , Langhout , R.D. , Palmieri , P.A. , Cortina , L.M. and Fitzgerald , L.F. ( 2002 ), “ The (un)reasonableness of reporting: antecedents and consequences of reporting sexual harassment ”, Journal of Applied Psychology , Vol. 87 No. 2 , pp. 230 - 242 .

Bertrand , M. and Duflo , E. ( 2017 ), “ Field experiments on discrimination ”, in Banerjee , A.V. and Duflo , E. (Eds), Handbook of Economic Field Experiments , Elsevier , Amsterdam , Vol. 1 , pp. 309 - 393 .

Buckman , S.R. , Choi , L.Y. , Daly , M.C. and Seitelman , L.M. ( 2021 ), The Economic Gains from Equity , Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Working Paper , San Francisco .

Calvo , E. , Mair , C. and Sarkisian , N. ( 2015 ), “ Individual troubles, shared troubles: the multiplicative effect of individual and country-level unemployment on life satisfaction in 95 Nations (1981-2009) ”, Social Forces , Vol. 93 No. 4 , pp. 1625 - 1653 .

Chay , K.Y. ( 1998 ), “ The impact of federal civil rights policy on black economic progress: evidence from the equal employment opportunity act of 1972 ”, Industrial and Labor Relations Review , Vol. 51 No. 4 , pp. 608 - 632 .

Cheong , C.W.H. and Sinnakkannu , J. ( 2014 ), “ Ethnic diversity and firm financial performance: evidence from Malaysia ”, Journal of Asia-Pacific Business , Vol. 15 No. 1 , pp. 73 - 100 , doi: 10.1080/10599231.2014.872973 .

Churchill , S.A. ( 2019 ), “ Firm financial performance in sub-Saharan Africa: the role of ethnic diversity ”, Empirical Economics , Vol. 57 No. 3 , pp. 1 - 14 .

Coleman , M.G. ( 2003 ), “ Job skill and Black male wage discrimination ”, Social Science Quarterly , Vol. 84 , pp. 892 - 906 .

Collins , W.J. ( 2003 ), “ The labor market impact of state-level anti-discrimination laws, 1940-1960 ”, Industrial and Labor Relations Review , Vol. 56 No. 2 , pp. 244 - 272 .

Couch , K.A. and Fairlie , R. ( 2010 ), “ Last hired, first fired? Black-white unemployment and the business cycle ”, Demography , Vol. 47 No. 1 , pp. 227 - 247 .

Creese , G. ( 2010 ), “ Erasing English language competency: African migrants in Vancouver, Canada ”, International Migration and Integration , Vol. 11 No. 3 , pp. 295 - 313 , doi: 10.1007/s12134-010-0139-3 .

Crenshaw , K. ( 1989 ), “ Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics ”, The University of Chicago Legal Forum , p. 139 .

del Mar Alonso-Almeida , M. ( 2014 ), “ Women (and mothers) in the workforce: worldwide factors ”, Women's Studies International Forum , Vol. 44 , pp. 164 - 171 .

Demetriou , C. ( 2016 ), “ The equality body finds that restrictions in access to self-employment for third country nationals amount to unlawful discrimination, Cyprus ”, European Commission , available at: https://www.equalitylaw.eu/downloads/3840-cyprus-the-equality-body-finds-that-restrictions-in-access-to-self-employment-for-third-country-nationals-amount-to-unlawful-discrimination-pdf-95-kb ( accessed 7 January 2022 ).

Derous , E. and Pepermans , R. ( 2019 ), “ Gender discrimination in hiring: intersectional effects with ethnicity and cognitive job demands ”, Archives of Scientific Psychology , Vol. 7 No. 1 , pp. 40 - 49 .

Di Stasio , V. and Larsen , E.N. ( 2020 ), “ The racialized and gendered workplace: applying an intersectional lens to a field experiment on hiring discrimination in five european labor markets ”, Social Psychology Quarterly , Vol. 83 No. 3 , pp. 229 - 250 .

Donohue , J.J. and Heckman , J. ( 1991 ), “ Continuous versus episodic change: the impact of civil rights policy on the economic status of blacks ”, Journal of Economic Literature , Vol. 29 No. 4 , p. 1603 .

Dostie , B. and Javdani , M. ( 2020 ), “ Immigrants and workplace training: evidence from Canadian linked employer–employee data ”, Industrial Relations , Vol. 59 No. 2 , pp. 275 - 315 .

Drydakis , N. ( 2012 ), “ Roma women in Athenian firms: do they face wage bias? ”, Ethnic and Racial Studies , Vol. 35 No. 12 , pp. 2054 - 2074 .

Erhardt , N.L. , Werbel , J.D. and Shrader , C.B. ( 2003 ), “ Board of director diversity and firm financial performance ”, Corporate Governance , Vol. 11 No. 2 , pp. 102 - 111 , doi: 10.1111/1467-8683.00011 .

Fredman , S. ( 2016 ), “ Intersectional discrimination in EU gender equality and non-discrimination law ”, European Commission .

Goldman , N. , Pebley , A.R. , Lee , K. , Andrasfay , T. and Pratt , B. ( 2021 ), “ Racial and ethnic differentials in COVID-19-related job exposures by occupational standing in the US ”, PLoS One , Vol. 16 No. 9 .

Gorod , B.J. ( 2007 ), “ Rejecting reasonableness: a new look at title VII's anti-retaliation provision ”, American University Law Review , Vol. 56 No. 6 , pp. 1469 - 1524 .

Greene , D.W. ( 2017 ), “ Splitting hairs: the Eleventh Circuit’s take on workplace bans against Black women’s natural hair in EEOC v. Catastrophe Management Solutions ”, University of Miami Law Review , Vol. 71 , p. 987 .

Hatch , S.L. , Gazard , B. , Williams , D.R. , Frissa , S. , Goodwin , L. , SelcoH , S.T. and Hotopf , M. ( 2016 ), “ Discrimination and common mental disorder among migrant and ethnic groups: findings from a South East London Community sample ”, Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology , Vol. 51 No. 5 , pp. 689 - 701 .

Herring , C. ( 2009 ), “ Does diversity pay?: race, gender, and the business case for diversity ”, American Sociological Review , Vol. 74 No. 2 , pp. 208 - 224 , doi: 10.1177/000312240907400203 .

Hunt , V. , Prince , S. , Dixon-Fyle , S. and Yee , L. ( 2018 ), Delivering Through Diversity , McKinsey & Company , Los Angeles .

Javdani , M. ( 2020 ), “ Visible minorities and job mobility: evidence from a workplace panel survey ”, The Journal of Economic Inequality , Vol. 18 , pp. 491 - 524 .

Javdani , M. and McGee , A. ( 2018 ), “ Labor market mobility and the early-career outcomes of immigrant men ”, IZA Journal of Development and Migration , Vol. 8 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 28 .

Justesen , P. ( 2016 ), “ Board of Equal Treatment ruling on so-called ‘language barrier’, Denmark ”, European Commission , available at: https://www.equalitylaw.eu/downloads/3920-denmark-board-of-equal-treatment-ruling-on-so-called-language-barrier-pdf-131-kb ( accessed 7 January 2022 ).

Keenan , J.P. ( 1990 ), “ Upper-level managers and whistleblowing: determinants of perceptions of company encouragement and information about where to blow the whistle ”, Journal of Business and Psychology , Vol. 5 No. 2 , pp. 223 - 235 .

Kislev , E. ( 2017 ), “ Deciphering the ‘ethnic penalty’ of immigrants in Western Europe: a cross-classified multilevel analysis ”, Social Indicators Research , Vol. 134 No. 2 , pp. 725 - 745 , doi: 10.1007/s11205-016-1451-x .

Law on Prevention of and Protection Against Discrimination ( 2010 ), “ Skopje: constitutional court of the republic of Macedonia ”, No. 82 , available at: https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/5aa12ad47.pdf .

Leck , J.D. and Saunders , D.M. ( 1992 ), “ Canada's employment equity act: effects on employee selection ”, Population Research and Policy Review , Vol. 11 No. 1 , p. 21 .

Leck , J.D. , St. Onge, S. and Lalancette , I. ( 1995 ), “ Wage gap changes among organizations subject to the employment equity act ”, Canadian Public Policy , Vol. 21 No. 4 , pp. 387 - 400 .

Lessem , R. and Nakajima , K. ( 2019 ), “ Immigrant wages and recessions: evidence from undocumented Mexicans ”, European Economic Review , Vol. 114 , pp. 92 - 115 .

Luksyte , A. , Waite , E. , Avery , D.R. and Roy , R. ( 2013 ), “ Held to a different standard: racial differences in the impact of lateness on advancement opportunity ”, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology , Vol. 86 No. 2 , pp. 142 - 165 .

Mayiya , S. , Schachtebeck , C. and Diniso , C. ( 2019 ), “ Barriers to career progression of Black African middle managers: the South African perspective ”, Acta Universitatis Danubius Oeconomica , Vol. 15 No. 2 .

Mora , C. and Undurraga , E.A. ( 2013 ), “ Racialisation of immigrants at work: labour mobility and segmentation of Peruvian migrants in Chile ”, Bulletin of Latin American Research , Vol. 32 No. 3 , pp. 294 - 310 , doi: 10.1111/blar.12002 .