- Career Center

- Digital Events

- Member Benefits

- Membership Types

- My Account & Profile

- Chapters & Affiliates

- Awards & Recognition

- Write or Review for ILA

- Volunteer & Lead

- Children's Rights to Read

- Position Statements

- Literacy Glossary

- Literacy Today Magazine

- Literacy Now Blog

- Resource Collections

- Resources by Topic

- School-Based Solutions

- ILA Digital Events

- In-Person Events

- Our Mission

- Our Leadership

- Press & Media

Literacy Now

- ILA Network

- Conferences & Events

- Literacy Leadership

- Teaching With Tech

- Purposeful Tech

- Book Reviews

- 5 Questions With...

- Anita's Picks

- Check It Out

- Teaching Tips

- In Other Words

- Putting Books to Work

- Tales Out of School

- Teaching Strategies

- Digital Literacies

- Foundational Skills

- ~7 years old (Grade 2)

- Innovating With Technology

- Administrator

- Digital Literacy

- 21st Century Skills

- Content Types

- Student Level

- Teacher Educator

- Special Education Teacher

- Reading Specialist

- Literacy Education Student

- Literacy Coach

- Classroom Teacher

- Job Functions

Reimagining Writing Instruction With Digital Tools

Often educators are advised to first consider their instructional goals and then find a digital tool that will help them in satisfying their teaching needs. However, we’ve found that by exploring digital tools and apps, teachers can see new possibilities for writing instruction. Therefore, learning about digital tools can act as an impetus for considering alternative approaches for strengthening writing skills.

At Kent State’s Research Center for Educational Technology , we have the privilege of collaborating with local teachers and students to integrate technology into their education and learning. Teacher and student cohorts visit our technologically advanced classroom for six weeks, five days a week, for two hours each day. This spring, we observed a second-grade teacher as she received situated professional development for integrating technology into her literacy instruction while her students had opportunities to explore digital tools for writing. On the basis of that implementation, we offer suggestions for programs and mobile applications that might best help educators facilitate writing activities and assignments in their classrooms.

Preparing students for writing

- Why It’s Important : Although the writing process is not a lockstep, there is strong evidence to support that students are more successful as writers when they understand it. Therefore, engaging students in prewriting and organizing activities before they start the first draft improves the quality of their writing.

- Digital Tools : Digital notebooks, such as Penzu , can serve as writing journals for students to generate ideas. In addition, applications like Popplet and Padlet can provide a space where students may independently or collaboratively brainstorm about topics or genre elements. By using these digital tools, students can make their planning visible as they can easily organize and reorganize ideas.

Multimodal compositions

- Why It’s Important : Technology is changing how people write. By composing with images, audio, and video, students learn to use multiple modes to convey meaning. For students who might be considered struggling writers, composing with a variety of modes can also help students be more strategic in their rhetorical decision making.

- Digital Tools : There are a number of apps and digital tools that allow students to produce multimodal compositions. Haiku Deck , Buncee , and Adobe Spark are a few tools we routinely use with teachers and students. However, we would also encourage teachers to think about how programming and coding with apps such as Daisy the Dinosaur and Scratch Junior might also help their students engage in digital storytelling.

Publishing students’ writing

- Why It’s Important : When students publish their writing for a wide audience, they have opportunities to receive authentic feedback. This process develops their writerly voice: They become more aware of who will be reading their composition and tailor their voice according to the purpose, the context, and the audience.

- Digital Tools : Digital platforms, such as Edmodo and Seesaw , are spaces for students to share their writing and then receive feedback.

Apps should align with pedagogy; however, teachers can reimagine how they can implement engaging, research-based writing instruction by exploring digital tools. This reimagination can also be facilitated through conversations with others; teachers grow by seeing the best practices of others. In addition to providing some examples in this blog, we also developed and have now opened access to SpedApps , a database with over 400 apps. This resource is not only a collection of mobile apps for content instruction (e.g., literacy) but is also a community where teachers can share the promise and pitfalls of mobile-based instruction as well as add their own favorite apps.

Kristine E. Pytash is an associate professor at Kent State University. Richard E. Ferdig is the Summit Professor of Learning Technologies and Professor, IT, Research Center for Educational Technologies. Enrico Gandolfi is a research fellow at Kent State University. Rachel Mathews is a doctoral student at Kent State University. This work was funded, in part, by a corporate gift from AT&T.

This article is part of a series from the Technology in Literacy Education Special Interest Group (TILE-SIG).

Ways That Digital Tools Can Help Students to Read Their Worlds

- Conferences & Events

- Anita's Picks

Recent Posts

- Going Beyond Appreciation This Teacher Appreciation Week: Celebrating Empathy, Gratitude, and Inspiration

- The Double Helix of Reading and Writing: Fostering Integrated Literacy

- Uplifting Student Voices: Reflections on the AERA/ILA Writing Project

- ILA & AERA Amplify Student Voices on Equity

- Member Spotlight: Tihesha Morgan Porter

- For Network Leaders

- For Advertisers

- Privacy & Security

- Terms of Use

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- The Impact of Digital Tools on Student Writing and How Writing is Taught in Schools

Table of Contents

- Part I: Introduction

- Part II: How Much, and What, do Today’s Middle and High School Students Write?

- Part III: Teachers See Digital Tools Affecting Student Writing in Myriad Ways

- Part IV: Teachers Assess Students on Specific Writing Skills

- Part V: Teaching Writing in the Digital Age

A survey of 2,462 Advanced Placement (AP) and National Writing Project (NWP) teachers finds that digital technologies are shaping student writing in myriad ways and have also become helpful tools for teaching writing to middle and high school students. These teachers see the internet and digital technologies such as social networking sites, cell phones and texting, generally facilitating teens’ personal expression and creativity, broadening the audience for their written material, and encouraging teens to write more often in more formats than may have been the case in prior generations. At the same time, they describe the unique challenges of teaching writing in the digital age, including the “creep” of informal style into formal writing assignments and the need to better educate students about issues such as plagiarism and fair use.

The AP and NWP teachers surveyed see today’s digital tools having tangible, beneficial impacts on student writing

Overall, these AP and NWP teachers see digital technologies benefitting student writing in several ways:

- 96% agree (including 52% who strongly agree) that digital technologies “allow students to share their work with a wider and more varied audience”

- 79% agree (23% strongly agree) that these tools “encourage greater collaboration among students”

- 78% agree (26% strongly agree) that digital technologies “encourage student creativity and personal expression”

The combined effect of these impacts, according to this group of AP and NWP teachers, is a greater investment among students in what they write and greater engagement in the writing process.

At the same time, they worry that students’ use of digital tools is having some undesirable effects on their writing, including the “creep” of informal language and style into formal writing

In focus groups, these AP and NWP teachers shared some concerns and challenges they face teaching writing in today’s digital environment. Among them are:

- an increasingly ambiguous line between “formal” and “informal” writing and the tendency of some students to use informal language and style in formal writing assignments

- the increasing need to educate students about writing for different audiences using different “voices” and “registers”

- the general cultural emphasis on truncated forms of expression, which some feel are hindering students willingness and ability to write longer texts and to think critically about complicated topics

- disparate access to and skill with digital tools among their students

- challenging the “digital tool as toy” approach many students develop in their introduction to digital tools as young children

Survey results reflect many of these concerns, though teachers are sometimes divided on the role digital tools play in these trends. Specifically:

- 68% say that digital tools make students more likely—as opposed to less likely or having no impact—to take shortcuts and not put effort into their writing

- 46% say these tools make students more likely to “write too fast and be careless”

- Yet, while 40% say today’s digital technologies make students more likely to “use poor spelling and grammar” another 38% say they make students LESS likely to do this

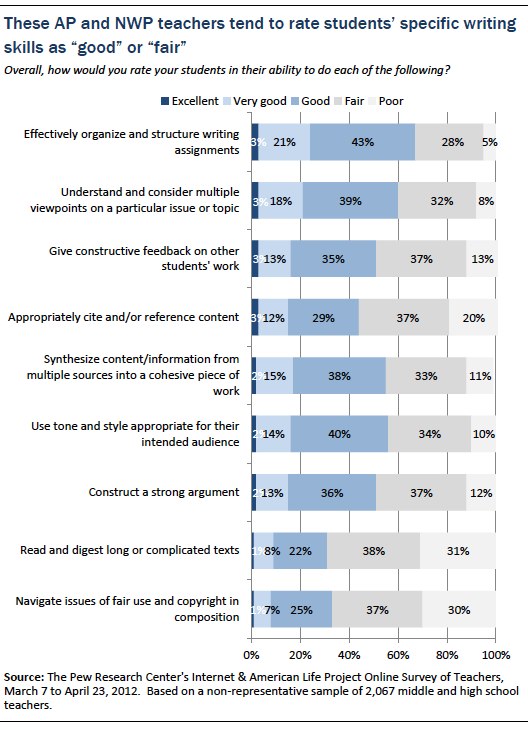

Overall, these AP and NWP teachers give their students’ writing skills modest marks, and see areas that need attention

Asked to assess their students’ performance on nine specific writing skills, AP and NWP tended to rate their students “good” or “fair” as opposed to “excellent” or “very good.” Students were given the best ratings on their ability to “effectively organize and structure writing assignments” with 24% of teachers describing their students as “excellent” or “very good” in this area. Students received similar ratings on their ability to “understand and consider multiple viewpoints on a particular topic or issue.” But ratings were less positive for synthesizing material into a cohesive piece of work, using appropriate tone and style, and constructing a strong argument.

These AP and NWP teachers gave students the lowest ratings when it comes to “navigating issues of fair use and copyright in composition” and “reading and digesting long or complicated texts.” On both measures, more than two-thirds of these teachers rated students “fair” or “poor.”

Majorities of these teachers incorporate lessons about fair use, copyright, plagiarism, and citation in their teaching to address students’ deficiencies in these areas

In addition to giving students low ratings on their understanding of fair use and copyright, a majority of AP and NWP teachers also say students are not performing well when it comes to “appropriately citing and/or referencing content” in their work. This is fairly common concern among the teachers in the study, who note how easy it is for students today to copy and paste others’ work into their own and how difficult it often is to determine the actual source of much of the content they find online. Reflecting how critical these teachers view these skills:

- 88% (across all subjects) spend class time “discussing with students the concepts of citation and plagiarism”

- 75% (across all subjects) spend class time “discussing with students the concepts of fair use and copyright”

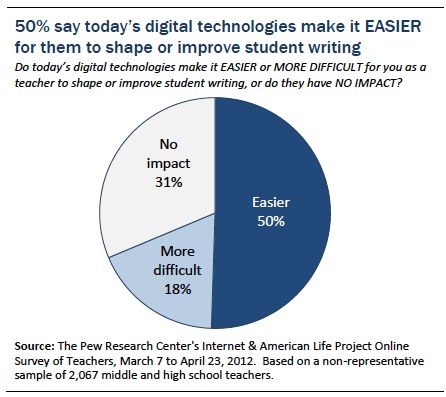

A plurality of AP and NWP teachers across all subjects say digital tools make teaching writing easier

Despite some challenges, 50% of these teachers (across all subjects) say the internet and digital tools make it easier for them to teach writing, while just 18% say digital technologies make teaching writing more difficult. The remaining 31% see no real impact.

Positive perceptions of the potential for digital tools to aid educators in teaching writing are reflected in practice:

- 52% of AP and NWP teachers say they or their students use interactive whiteboards in their classes

- 40% have students share their work on wikis, websites or blogs

- 36% have students edit or revise their own work and 29% have students edit others’ work using collaborative web-based tools such as GoogleDocs

In focus groups, teachers gave a multitude of examples of the value of these collaborative tools, not only in teaching more technical aspects of writing but also in being able to “see their students thinking” and work alongside students in the writing process. Moreover, 56% say digital tools make their students more likely to write well because they can revise their work easily.

These middle and high school teachers continue to place tremendous value on “formal writing”

While they see writing forms and styles expanding in the digital world, AP and NWP teachers continue to place tremendous value on “formal writing” and try to use digital tools to impart fundamental writing skills they feel students need. Nine in ten (92%) describe formal writing assignments as an ��essential” part of the learning process, and 91% say that “writing effectively” is an “essential” skill students need for future success.

More than half (58%) have students write short essays or responses on a weekly basis, and 77% assigned at least one research paper during the 2011-2012 academic year. In addition, 41% of AP and NWP teachers have students write weekly journal entries, and 78% had their students create a multimedia or mixed media piece in the academic year prior to the survey.

Almost all AP and NWP teachers surveyed (94%) encourage students to do some of their writing by hand

Alongside the use of digital tools to promote better writing, almost all AP and NWP teachers surveyed say they encourage their students to do at least some writing by hand. Their reasons are varied, but many teachers noted that because students are required to write by hand on standardized tests, it is a critical skill for them to have. This is particularly true for AP teachers, who must prepare students to take AP exams with pencil and paper. Other teachers say they feel students do more active thinking, synthesizing, and editing when writing by hand, and writing by hand discourages any temptation to copy and paste others’ work.

About this Study

The basics of the survey.

These are among the main findings of an online survey of a non-probability sample of 2,462 middle and high school teachers currently teaching in the U.S., Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, conducted between March 7 and April 23, 2012. Some 1,750 of the teachers are drawn from a sample of advanced placement (AP) high school teachers, while the remaining 712 are from a sample of National Writing Project teachers. Survey findings are complemented by insights from a series of online and in-person focus groups with middle and high school teachers and students in grades 9-12, conducted between November, 2011 and February, 2012.

This particular sample is quite diverse geographically, by subject matter taught, and by school size and community characteristics. But it skews towards educators who teach some of the most academically successful students in the country. Thus, the findings reported here reflect the realities of their special place in American education, and are not necessarily representative of all teachers in all schools. At the same time, these findings are especially powerful given that these teachers’ observations and judgments emerge from some of the nation’s most advanced classrooms.

In addition to the survey, Pew Internet conducted a series of online and offline focus groups with middle and high school teachers and some of their students and their voices are included in this report.

The study was designed to explore teachers’ views of the ways today’s digital environment is shaping the research and writing habits of middle and high school students, as well as teachers’ own technology use and their efforts to incorporate new digital tools into their classrooms.

About the data collection

Data collection was conducted in two phases. In phase one, Pew Internet conducted two online and one in-person focus group with middle and high school teachers; focus group participants included Advanced Placement (AP) teachers, teachers who had participated in the National Writing Project’s Summer Institute (NWP), as well as teachers at a College Board school in the Northeast U.S. Two in-person focus groups were also conducted with students in grades 9-12 from the same College Board school. The goal of these discussions was to hear teachers and students talk about, in their own words, the different ways they feel digital technologies such as the internet, search engines, social media, and cell phones are shaping students’ research and writing habits and skills. Teachers were asked to speak in depth about teaching research and writing to middle and high school students today, the challenges they encounter, and how they incorporate digital technologies into their classrooms and assignments.

Focus group discussions were instrumental in developing a 30-minute online survey, which was administered in phase two of the research to a national sample of middle and high school teachers. The survey results reported here are based on a non-probability sample of 2,462 middle and high school teachers currently teaching in the U.S., Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Of these 2,462 teachers, 2,067 completed the entire survey; all percentages reported are based on those answering each question. The sample is not a probability sample of all teachers because it was not practical to assemble a sampling frame of this population. Instead, two large lists of teachers were assembled: one included 42,879 AP teachers who had agreed to allow the College Board to contact them (about one-third of all AP teachers), while the other was a list of 5,869 teachers who participated in the National Writing Project’s Summer Institute during 2007-2011 and who were not already part of the AP sample. A stratified random sample of 16,721 AP teachers was drawn from the AP teacher list, based on subject taught, state, and grade level, while all members of the NWP list were included in the final sample.

The online survey was conducted from March 7–April 23, 2012. More details on how the survey and focus groups were conducted are included in the Methodology section at the end of this report, along with focus group discussion guides and the survey instrument.

There are several important ways the teachers who participated in the survey are unique, which should be considered when interpreting the results reported here. First, 95% of the teachers who participated in the survey teach in public schools, thus the findings reported here reflect that environment almost exclusively. In addition, almost one-third of the sample (NWP Summer Institute teachers) has received extensive training in how to effectively teach writing in today’s digital environment. The National Writing Project’s mission is to provide professional development, resources and support to teachers to improve the teaching of writing in today’s schools. The NWP teachers included here are what the organization terms “teacher-consultants” who have attended the Summer Institute and provide local leadership to other teachers. Research has shown significant gains in the writing performance of students who are taught by these teachers. 1

Moreover, the majority of teachers participating in the survey (56%) currently teach AP, honors, and/or accelerated courses, thus the population of middle and high school students they work with skews heavily toward the highest achievers. These teachers and their students may have resources and support available to them—particularly in terms of specialized training and access to digital tools—that are not available in all educational settings. Thus, the population of teachers participating in this research might best be considered “leading edge teachers” who are actively involved with the College Board and/or the National Writing Project and are therefore beneficiaries of resources and training not common to all teachers. It is likely that teachers in this study are developing some of the more innovative pedagogical approaches to teaching research and writing in today’s digital environment, and are incorporating classroom technology in ways that are not typical of the entire population of middle and high school teachers in the U.S. Survey findings represent the attitudes and behaviors of this particular group of teachers only, and are not representative of the entire population of U.S. middle and high school teachers.

Every effort was made to administer the survey to as broad a group of educators as possible from the sample files being used. As a group, the 2,462 teachers participating in the survey comprise a wide range of subject areas, experience levels, geographic regions, school type and socioeconomic level, and community type (detailed sample characteristics are available in the Methods section of this report). The sample includes teachers from all 50 states, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. All teachers who participated in the survey teach in physical schools and classrooms, as opposed to teaching online or virtual courses.

English/language arts teachers make up a significant portion of the sample (36%), reflecting the intentional design of the study, but history, social science, math, science, foreign language, art, and music teachers are also represented. About one in ten teachers participating in the survey are middle school teachers, while 91% currently teach grades 9-12. There is wide distribution across school size and students’ socioeconomic status, though half of the teachers participating in the survey report teaching in a small city or suburb. There is also a wide distribution in the age and experience levels of participating teachers. The survey sample is 71% female.

About the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project

The Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project is one of seven projects that make up the Pew Research Center, a nonpartisan, nonprofit “fact tank” that provides information on the issues, attitudes and trends shaping America and the world. The Project produces reports exploring the impact of the internet on families, communities, work and home, daily life, education, health care, and civic and political life. The Pew Internet Project takes no positions on policy issues related to the internet or other communications technologies. It does not endorse technologies, industry sectors, companies, nonprofit organizations, or individuals. While we thank our research partners for their helpful guidance, the Pew Internet Project had full control over the design, implementation, analysis and writing of this survey and report.

About the National Writing Project

The National Writing Project (NWP) is a nationwide network of educators working together to improve the teaching of writing in the nation’s schools and in other settings. NWP provides high-quality professional development programs to teachers in a variety of disciplines and at all levels, from early childhood through university. Through its nearly 200 university-based sites serving all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, NWP develops the leadership, programs and research needed for teachers to help students become successful writers and learners. For more information, visit www.nwp.org .

- More specific information on this population of teachers, the training they receive, and the outcomes of their students are available at the National Writing Project website at www.nwp.org . ↩

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Age & Generations

- Digital Divide

- Education & Learning Online

- Online Search

- Platforms & Services

- Teens & Tech

- Teens & Youth

Teens and Video Games Today

As biden and trump seek reelection, who are the oldest – and youngest – current world leaders, how teens and parents approach screen time, who are you the art and science of measuring identity, u.s. centenarian population is projected to quadruple over the next 30 years, most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Writing Instruction to Support Literacy Success: Volume 7

Table of contents, rethinking writing products and processes in a digital age.

Writing as a hot topic in literacy has recently gained a foothold in terms of importance to academic and career success, finally receiving the attention it warrants and thus, this chapter provides timely information about how to teach writing products and processes in the 21st century.

Design/methodology/approach

Through a historical examination of writing instruction, this chapter provides a contextual lens for how writing has not always been a priority in the field of literacy; how writing and reading are interconnected; and how differing theories aim to explain writing development.

Writing has taken on a balanced approach between writing for product and writing as a practice. Teacher pedagogy has been heavily influenced by the advent of high-stakes assessments. Other factors such as maintaining motivation and engagement for writing affect student performance. Writing and reading benefit from an integrated instructional approach.

Practical implications

Elements of writing instruction are deconstructed to provide information for teachers to support students’ confidence in their writing abilities, build their identity as writers, and promote individualization and creativity to flourish through independence.

Turning around the Progress of Struggling Writers: Key Findings from Recent Research

To identify features of teacher support associated with children who made accelerated progress in writing in an early literacy intervention.

Mixed methods were used to describe the paths, rates, variability, and potential sources of change in the writing development of 24 first grade students who participated in an early literacy intervention for 20 weeks. To describe the breadth and variability of change in children’s writing within a co-constructed setting, two groups who made high and low progress were identified.

We focus on one child, Paul, who made high progress (became more independent in the writing of linguistically complex messages) and the features of teacher support that this child received compared to those who made lower progress. We compare him to another child, Emma, who made low progress. Teacher support associated with high progress included a conversational style and flexibility to adapt to the child’s message intent as the student composed, supporting students to write linguistically more complex and legible messages, and supporting students to orchestrate a broad range of problem-solving behaviors while writing.

We describe how teachers can support children to gradually take control of the composition process, how they can recognize complexity in early written messages and we provide suggestions as to how teachers can systematically assess, observe, and support children’s self-regulation of the writing process.

Accelerating Student Progress in Writing: Examining Practices Effective in New Zealand Primary School Classrooms

Writing performance is an international issue and, while the quality of instruction is key, features of the context shape classroom practice. The issues and solutions in terms of teacher practice to address underachievement need to be considered within such a context and the purpose of the chapter is to undertake such an analysis.

Data from five different research projects (national and regional) of the author and colleagues, and two studies of the author’s doctoral students, are synthesized to identify both common and specific elements of primary/elementary (years 1–8, ages 5–13) teacher practice in writing. These data provide an indication of the practices which appear to be the most powerful levers for developing writing and for accelerating student progress in the context in which the teachers work. These practices are discussed.

The identified practices are: (1) acquiring and applying deep knowledge of your writers; (2) making connections with, and validating, relevant cultural and linguistic funds of knowledge; (3) aligning learning goals in writing with appropriately designed writing tasks and ensuring that students understand what they are learning and why; (4) providing quality feedback; (5) scaffolding self-regulation in writers; (6) differentiating instruction (while maintaining high expectations) and (7) providing targeted and direct instruction at the point of need. A discussion and a description of writing-specific instantiations of these help to illustrate their nature and the overlaps and interconnections.

As much of the data are drawn from the practices of teachers deemed to be highly effective, classroom practices associated with these teachers can be targeted as a means to improve the quality of instruction more widely in the particular context.

Ideas as a Springboard for Writing in K-8 Classrooms

To review and synthesize findings from peer-reviewed research related to students’ sources of ideas for writing, and instructional dimensions that affect students’ development of ideas for composition in grades K-8.

The ideas or content expressed in written composition are considered critical to ratings of writing quality. We utilized a Systematic Mixed Studies Review (SMSR) methodological framework (Heyvaert, Maes, & Onghena, 2011) to explore K-8 students’ ideas and writing from a range of theoretical and methodological perspectives.

Students’ ideas for writing originate from a range of sources, including teachers, peers, literature, content area curriculum, autobiographical/life experiences, popular culture/media, drawing, and play. Intertextuality, copying, social dialogue, and playful peer interactions are productive strategies K-8 writers use to generate ideas for composing, in addition to strategies introduced through planned instruction. Relevant dimensions of instruction include motivation to write, idea planning and organization, as well as specific instructional strategies, techniques, and tools to facilitate idea generation and selection within the composition process.

A permeable curriculum and effective instructional practices are crucial to support students’ access to a full range of ideas and knowledge-based resources, and help them translate these into written composition. Instructional practices for idea development and writing: (a) connect reading and writing for authentic purposes; (b) include explicit modeling of strategies for planning and “online” generation of ideas throughout the writing process across genre; (c) align instructional focus across reading, writing, and other curricular activities; (d) allow for extended time to write; and (e) incorporate varied, flexible participation structures through which students can share ideas and receive teacher/peer feedback on writing.

Process with a Purpose: Low-Stakes Writing in the Secondary English Classroom

To describe how low-stakes writing can assist teachers in eliciting greater student engagement and involvement in their own writing by focusing the stages of the writing process more on student thinking than on the surface structure of their writing.

This chapter examines some of the important research literature addressing process writing in general and low-stakes writing in particular. The authors’ experiences with teaching English in the secondary classroom inform their analysis of implementing low-stakes writing assignments as part of the writing process.

The authors describe how using non-judgmental feedback on low-stakes writing assignments allows the teacher and students to have conversations on paper which are intended to help students explore, expand, and clarify their own thinking about a topic. By establishing a continuing conversation on paper with the students about their writing, the teacher takes on the role of “trusted ally” in the writing process, rather than the more traditional role of an arbiter of writing conventions.

Although the presumptive focus of writing instruction for the last two decades has been on the writing process, the tendency to turn the individual steps of the writing process into discrete writing products in a formulaic manner can cause many important parts of the writing process itself to be either overlooked or given short shrift. This chapter provides useful descriptions of ways in which low-stakes writing assignments can afford teachers the means by which to focus their students’ attention on key portions of the writing process so that their writing products are ultimately improved.

Learning Language and Vocabulary in Dialogue with the Real Audience: Exploring Young Writers’ Authentic Writing and Language Learning Experiences

To explore the potential of conversations with an authentic audience through blogging for enriching in young writers the understanding of the communicative function of writing, specifically language and vocabulary use.

We situate our work in the language acquisition model of language learning, in which learners develop linguistic competence in the process of speaking and using language (Krashen, 1988; Tomasello, 2005). We also believe that language learning benefits from formal instruction (Krashen, 1988). As such, in our work, we likened engaging in blogging to learning a language (here, more broadly conceived as learning to write) through both natural communication (acquisition) and prescription (instruction), and we looked at these forms of learning in our study.

We were interested in the communicative function of language learning (Halliday, 1973; 1975; Penrod, 2005) among young blog writers, because we see language learning as socially constructed through interaction with other speakers of a language (Tomasello, 2005; Vygotsky, 1978).

The readers and commenters in this study supported young writers in their language study by modeling good writing and effective language use in their communication with these writers. Young writers also benefited from direct instruction through interactions with adults beyond classroom teachers, in our case some of the readers and commenters.

Blogging can extend conversations to audiences far beyond the classroom and make writing a more authentic endeavor for young writers. Teachers should take advantage of such a powerful tool in their writing classrooms to support their students’ language study and vocabulary development.

Understanding a Digital Writing Cycle: Barriers, Bridges, and Outcomes in Two Second-Grade Classrooms

To describe how the digital writing experiences of two collaborating second-grade classrooms are representative of a digital writing cycle that includes barriers, bridges, and outcomes. Additionally, this chapter aims to link theory and practice for teachers working with an increasingly younger generation of multimodal learners by connecting teacher reflections to New Literacies perspectives.

The current study is informed by multiple perspectives contributing to New Literacies research. These perspectives blend the traditional disciplines of literacy and technology while recognizing both the growing use of digital tools and the new skills and dispositions required for writing. This chapter uses multiple data points to present (1) how the teachers approached implementation of digital writing tools, (2) how students responded to the use of digital writing tools, and (3) how the digital-related writing experiences aligned with key tenets of New Literacies research.

The authors present student barriers for full participation with corresponding bridges implemented by teachers to help students navigate in the digital writing classroom. Each finding is supported with examples from student and teacher interviews as well as classroom observations and artifacts. The chapter concludes with a “lessons learned” section from the perspective of the teachers in the study with each tenet supporting a New Literacies perspective by addressing key considerations of multimodal environments such as the importance of early opportunities for teaching and learning with new literacies, the need to help inexperienced students bridge technical skill gaps, and the benefit of social relationships in the digital community.

By adapting findings of the study to a digital writing cycle, this chapter discusses how guiding principles of New Literacies research reflects classroom practice, thereby granting current and future teachers a practical guide for bridging theory and practice for implementing digital writing experiences for elementary students in multimodal environments.

Classroom Writing Community as Authentic Audience: The Development of Ninth-Graders’ Analytical Writing and Academic Writing Identities

To describe the role one classroom writing community played in shaping students’ understandings of the analytical writing genre; and to discuss the impact the community had on students’ developing academic writing identities.

While research has demonstrated the impact of classroom writing communities on student writing practices and identities at the elementary level (Dyson, 1997) and for secondary students engaged in fiction writing (Halverson, 2005), less is known about the role classroom writing communities may play for secondary students who are learning to write in academic discourses. This chapter explores the practices of one such classroom community and discusses the ways the community facilitated students’ introduction to the discourse of analytical writing.

The teacher turned the classroom writing community into an authentic audience, and in so doing, he developed students’ understandings of the analytical writing genre and their growing identities as academic writers. First, he used the concept of immediate audience (i.e., writing to persuade real readers) as the primary rationale for students to follow the outlined expectations for analytical writing. Second, he used inquiry discussions around student work (i.e., interacting with other members of the writing community) to prepare students for a future audience of prospective independent school English classrooms.

By turning the classroom writing community into an authentic audience through inquiry discussions, teachers can develop students’ deep and flexible understandings of a potentially unfamiliar writing genre. Furthermore, by employing the classroom writing community as a support for moving students through moments of struggle, teachers implicate students’ expertise as academic writers, thereby facilitating their willingness to take on academic writing identities.

Engaging Students in Multimodal Arguments: Infographics and Public Service Announcements

To present the instructional activities of an intervention enacted in two formative experiment studies. The goal of these studies was to improve students’ argumentative writing, both conventional and digital, multimodal.

This chapter provides the instructional steps taken by high-school teachers as they integrated multimodal argument projects into their classroom, describing the planning and instructional activities needed to teach students both the elements of argument and the practice of digital, multimodal design.

The author discusses the practical pedagogical steps and considerations needed to have students create digital, multimodal arguments in the form of infographics and public service announcements. Students were engaged in the creation of these arguments; however, practical considerations are discussed for both task complexity and the merger between digital and conventional writing.

Research suggests that integrating digital tools and multimodality into classrooms may be needed and valued, but practical suggestions for this integration are lacking. This chapter provides the needed pedagogical application of digital tools and multimodality to academic instruction.

The Use of Google Docs Technology to Support Peer Revision

To investigate sixth-grade students with learning disabilities and their use of Google Docs to facilitate peer revision for informational writing.

A qualitative case study is used to examine how students used Google Docs to support peer revision. Constant comparative analysis with a separate deductive revision and overall writing quality analysis was used.

The findings indicate that students used key features in Google Docs to foster collaboration during revision, they made improvements in overall writing quality, their revisions focused on adding informational elements to support organization of their writing and revisions were mostly made at the sentence level, and students were engaged while using the technology.

We postulate that the use of peer revision coupled with Google Docs technology can be a powerful tool for improving student writing quality and for changing the role of the writing teacher during revision. The use of peer revision should be accompanied with strong explicit instruction using the gradual release of responsibility model so that peer tutors are well-trained. Writing teachers can use Google Docs to monitor and assess writing and peer collaboration and then use this knowledge to guide whole and small-group instruction or individual conferences.

A Framework for Literacy: A Teacher–Researcher Partnership Considers the “C-S-C Paragraph” and Literacy Outcomes

To describe the role of teaching “the paragraph” in furthering literacy goals. The study considers one concept, the Claim-Support-Conclusion Paragraph (CSC) as a curricular and pedagogic intervention supporting writing and academic success for the marginalized students in two classrooms.

While this study corresponds to a gap in the literature of writing instruction (and paragraphing), it takes as its model the development of comprehensive collaborations where researcher-scholars embed themselves in the real practices of school classrooms. A fully-fledged partnership between researcher, practitioners, is characteristic of “practice embedded educational research,” or PEER (Snow, 2015), with analysis of data following qualitative and case study methodology.

Practice-embedded research in this partnership consistently revealed several important themes, including the effective use of the CSC paragraph functions as a critical common denominator across rich curricular choices. Extensive use of writing practice drives increased literacy fluency for struggling students, and writing practice can be highly integrated with reading practice. Effective writing instruction likely includes analytic and interpretive purposes, as well as personal, aesthetic writing, and teaching good paragraphing is intertwined with all of these genres in a community that values writing routines.

Greater academic success for the marginalized students in their classroom necessitates the use of a variety of scaffolds, and writing instruction can include the CSC paragraph as a means to develop academic literacies, including argumentation. Collaborative and innovative work with curriculum within a PEER model may have affordances for developing practitioner and researcher knowledge about writing instruction.

Powerful Writing Instruction: Seeing, Understanding, and Influencing Patterns

Our purpose in this chapter is to examine the implementation of a set of lesson frameworks to set conditions for teachers to deal with the complex challenges related to writing instruction in a high-stakes testing environment. These lessons provided a flexible framework for teachers to use in tutorials and in summer writing camps for students who struggle to pass the state-mandated tests, but they also build shared understandings about writing as a complex adaptive system.

We look to two sources for our theoretical framework: the study of complex adaptive systems and research-based writing instruction. In the chapter we summarize insights from these sources as a list of patterns that we want to see in powerful writing instruction. The analysis presented here is based on open-ended interviews of 17 teachers in one of the partner districts. The results of an inductive analysis of these transcripts is combined with a summary of 9th and 10th grade test results to inform the next iteration of this work.

Our findings suggest a shift toward patterns that imply shared understandings that writing and writing instruction require dialogue, inquiry, adaptability, and authenticity. These lesson frameworks, rather than limiting teacher’s flexibility and responsiveness, provide just enough structure to encourage flexibility in writing instruction. Using these frameworks, teachers can respond to their students’ needs to support powerful writing.

This set of lesson frameworks and the accompanying professional development hold the potential to build coherence in writing instruction across a campus or district, as it builds shared understandings and practices. We look forward to further implementation, adaptation, and documentation in diverse contexts.

Fourth Graders as Researchers: Authors and Self-Illustrators of Informational Books

To facilitate teacher–researcher collaboration in order to implement an informational writing research project using the framework of Browse, Collect, Collate, and Compose embedded within the writing workshop.

This study was conducted using a qualitative (Merriam, 1998) method of inquiry, more specifically, case study research design. A researcher and a practitioner came together to explore problems related to authentic use of expository genre and collaborated to help fourth graders write informational books.

The development of an authentic informational book was in contrast to the inauthentic purposes whereby students studied expository writing as preparation for statewide testing of student writing achievement. The study advocates the usage of authentic literacy contexts where students can enjoy writing for personal purposes.

Collaboration between classroom teachers of writing and researchers contributes to the theoretical and practical knowledge base of the teacher and researcher. Overall literacy development is enhanced when students read and write out of their own interest. Students use trade books as mentor texts to compose and create their informational books. The value of seeing fourth graders as researchers and making an informational book serves the authentic purpose of writing.

Seniors, Scholars, Researchers: Using an Inquiry Approach to Writing the Research Paper

This chapter presents a description of a pilot course for 12th-grade students in research methods and writing, using Guided Inquiry Design to develop students’ critical literacy and information literacy skills.

Using a practitioner inquiry methodology, this teacher research study makes use of qualitative data to examine student perspectives and experiences, teaching artifacts and student work samples. The research seeks to identify ways students practice critical literacies when engaged with inquiry learning, as well as the characteristics of a classroom learning community designed to support students’ experiences in inquiry learning.

Teachers of research-based writing are encouraged to adopt a guided inquiry approach to their instruction in which they flip the script on the thesis statement, allow for an almost uncomfortable amount of exploratory reading, put the focus on the process instead of the product, and form a guided inquiry team with the school librarian.

This chapter serves as a resource for practicing teachers, teacher researchers, and teacher educators assisting new teachers in embedding critical inquiry skill development in student writing.

Augmenting Academic Writing Achievement for All Students

Writing is an act of expressive communication achieved through the medium of print. It is but one of three modes of linguistic communication. The other expressive mode is speaking, while listening and reading comprise the two receptive modes. The purpose of this chapter is to present the impact of a study in which students read and discussed expository poetry. Then they exchanged ideas relating to scientific concepts in the poems with students in a different group via pen pal letters. We analyzed these pen pal letters over four weeks to determine the influence of writing opportunities in an atmosphere rich in all four aspects of linguistic communication, involving authentic communication between students and within a community of learners.

Design/methodology/Approach

Six of Brod Bagert’s unpublished poems concerned with science concepts were read by students in Collaborative Discover Groups (CDG) in two third-grade classes. After the groups discussed the poems, a mini-lesson on one of the Six Traits of Writing followed, and the students responded individually to a teacher-generated prompt related to the specific poem. The responses were in the form of pen pal letters to students in another class who had just read the same poem, received the same teacher-directed mini-lesson, and had had a similar discussion in their respective CDG. The data gleaned from these letters provide information demonstrating the effect of emphasizing all linguistic facets synergistically in a social, communicative setting. Both the processes and the findings will be discussed.

Analysis of the pen pal letters third-grade students wrote over four weeks showed the following patterns. (1) There was an increase in the discursive nature of the writing. (2) The incidence of rhetorical questioning, using A + B = C reasoning, and evaluative thinking was present in the fifth set of letters, and not in the first. Additionally, the number of sentences per letter increased from the first to the fifth, and the number of words per letter increased from approximately 50 words per letter to 75 words per letter. It appears that the linguistically synergistic communicative processes employed in this study are reflected in the increased sophistication and communicative nature of these writings.

The data revealed the importance of including the sociocultural tenants in the classroom, emphasizing that reading, writing, speaking, and listening are all a part of the same phenomenon. Together they strengthen and support each other.

- Evan Ortlieb

- Earl H. Cheek, Jr.

- Wolfram Verlaan

We’re listening — tell us what you think

Something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

- Our Mission

Why Digital Writing Matters in Education

Writing teachers like me (and perhaps like you) have been caught in a tight spot for some time now. On the one hand, computing technologies have radically transformed the meaning of "writing." On the other hand, high stakes assessments and their impact on teaching have limited what counts as writing in school.

As a teacher, I feel pulled in different directions. Thankfully, there are some good educational resources available. The National Writing Project recently published Because Digital Writing Matters: Improving Student Writing in Online and Multimedia Environments by Danielle Nicole DeVoss, Elyse Eidman-Aadahl and Troy Hicks. Their book is a good resource for teachers interested in thoughtfully incorporating digital writing into their teaching, and it also will point readers toward other high-quality resources. In the spirit of their book, I am going to take up the issue of why digital writing matters, focusing on two issues:

- Digital writing challenges what counts as writing and reveals the gap between how writing works in the world and how we teach it in schools.

- Digital writing platforms and services are ways to innovate instruction and learning.

Why Writing Matters

I always find it worth starting with why writing matters in education and in life. In school, writing is a key language skill (if not a subject) and also supports learning in other content areas. In a knowledge society, written expression shapes success for individuals and groups. Because of computer networks, youth now in school will write more than any prior generation in human history. Yet we pay relatively little attention to writing in school, which is why the National Commission on Writing has called writing the " forgotten R ."

A second Commission report concluded that writing is a "threshold skill" for hiring and promotion among professional employees. Those who cannot write and communicate clearly will have difficulty landing a job and little chance of promotion. Leadership positions are out of the question.

The "Digital" in Digital Writing

What distinguishes "digital" writing? Yes, technologies matter, particularly networks, which really are the big change agent in the last twenty years. But the most powerful changes are cultural. Digital writing is networked, and because of this, often deeply collaborative or coordinated. Wikipedia, for instance, is not possible without a computer network. But it is the cultural changes in how we write that an example like Wikipedia makes clear. Or consider Facebook, which is perhaps the most pervasive and commonplace collaborative writing platform in human history.

But digital technologies also have made it easy to "write" in all sorts of new ways. We can use more modes and resources, such as image, sound and video. We can remix the work of others -- with and without permission -- and share what we create more easily than ever before. And people do, all the time, and for all sorts of compelling reasons. Many of these people are our students.

It is often said that technologies don't get interesting until they become culturally meaningful. I think this is the case with the technologies of digital writing, and I can't help but contrast the dynamic ways that writing is changing in the world with what happens too often in my school. According to a recent Pew Internet and American Life survey , 86 percent of teenagers believe that writing well is important to success in life. But they don't see most of the writing that they do in their lives as "real" writing. Yet, ironically, it is the writing in which they find the most pleasure, that they do most eagerly and, arguably, that they do most successfully.

Making "the Digital" Work for Teaching and Learning

One of the problems worth solving is how to scale high quality writing instruction in ways that enrich the lives of teachers and students. We know what works in writing instruction:

- Engaged teachers and engaging environments

- Direct writing instruction and practice

- Revision focused on higher order concerns, guided by review feedback and informed by shared criteria

High quality writing instruction can also be expensive and time consuming, and often schools feel as if they can't do it. Or, as a cost-saving measure, technologies like machine grading are seen as a substitute for teaching.

But the same digital technologies that enable communication and collaboration might help teachers design technologies that make their teaching lives richer and their students more productive. We have been inventing technologies like this out of our own teaching, such as Eli , a service that supports peer learning in writing. Increasingly, there are other services available that extend the ability of computer networks to be tools for learning in writing (see, for example, Crocodoc ). We need many more efforts to support and share the innovations of teachers wrestling with how to teach digital writing in their schools.

There is no question that we have been witnessing an explosion of digital writing for some time now. We are living through a period of particularly rapid changes in how we write. Digital writing matters, and our challenge is to figure out how to be useful to those interested in leveraging these new writing platforms with thoughtfulness and power.

5 ways to integrate digital content into literacy instruction today

- March 26, 2019

- eSchool Media Contributors

As Discovery Education’s senior vice president of teaching and learning, I am constantly in communication with superintendents, principals, teachers and other educators about how to improve student literacy. This conversation often emanates from a discussion on the most effective way to “go digital” while simultaneously improving the reading, writing, speaking, and listening skills of all students. During these conversations, I’ve found that while there is unanimous agreement that instruction has evolved significantly (and positively) over the last few years, technology’s influence on literacy instruction has not changed significantly.

However, it’s a fact that today’s world is a digital world and we need to ensure that we are teaching students not only the traditional comprehension and composition skills associated with paper and pencil, but also the new skills of reading and writing digital texts. After all, there are definite differences between reading a book and reading a website or writing a blog and writing a literary essay.

The effective and intentional use of digital content in literacy instruction will not only engage students, but it may also strengthen and increase their literacy development. Take, for example, Ted Hasselbring’s research on using technology to increase the achievement of struggling readers. He reminds us that we know what good reading instruction looks like; we need to find technology to support that.

At Discovery Education we have a wide variety of digital curriculum resources, including our digital textbook series, or Techbooks, that include important and useful features like changing Lexiles or reading text aloud to support students as they transact with content area text. But, those digital curriculum resources, as Hasselbring states, must be used in conjunction with good reading instruction, and for that matter, all literacy instruction.

Here are five ways that you can integrate digital content into your reading and writing instruction to foster, build and ultimately, increase the literacy skills of all of your students:

- Use video to build the background knowledge of your students as a scaffold into complex texts or complex content. Think about some of the great novels that you read with students in your classrooms. As I reflect back on my experiences as a teacher, I’ll never forget reading aloud Esperanza Rising with my fifth graders or walking into a high school classroom where the teacher was reading the picture book Unspoken: A Story From the Underground Railroad to her students. These books have amazing stories with amazing words. Students learn a lot of history from these types of stories. However, using video clips to build their knowledge and understanding of the time periods when these stories occurred will make the literary experience richer and increase their ability to apply comprehension strategies like visualization and inferencing. Resources like Discovery Education Streaming provides teachers with thousands of video clips to pair with texts; consider using these types of curricular resources prior to reading texts or before introducing complex content to scaffold your students’ understanding. Think of it as giving your students a picture in their head on which to hang the words they are reading or hearing.

- Develop domain-specific vocabulary through a multimodal approach. Everyone loves a good glossary! It’s one of the early skills that we teach young readers as they read informational texts. Look at the bold-faced word. What do we do with that word? I’m sure this sounds familiar. I’m also pretty sure that the experience of going to the glossary, finding the word, reading the definition and still not understanding it, is also familiar. What if, however, along with the definition, there was an image, and a video clip and an animation, or other types of media to help you understand? Vocabulary is critical to reading and writing success. As you introduce new vocabulary to your students, particularly domain-specific words like photosynthesis or peninsula, integrate different types of digital content into your instruction or consider having your students build their own digital glossaries.

- Incorporate digital content into explicit reading instruction. In planning your next small group reading lesson, model for students how to read a digital text. How does the right navigation of a digital text help your comprehension? When do you click the hyperlink? Do you read the text first and then watch the video? These are different types of skills that teachers need to model for students and then, engage them in guided practice. However, reading a digital text is only one example of using digital content during explicit instruction. Think about teaching your students how to read a digital image or how to “read” an animation. While the skills and strategies for reading printed and digital content might be the same, how and when they are used looks different.

- Cultivate different types of writing with digital content. Turn off the sound of a short video clip and have students write the narration. Show an animation of the water cycle and have students write the process in step-by-step format. Watch a video on how to take care of a cat and another one on how to take care of a dog, then have students write a compare and contrast piece. Literacy standards across various states require students to write narrative, informative and argumentative pieces. Digital content not only fosters these types of writing, it provides the opportunity to write in a variety of formats while differentiating the domains of focus, content, organization and style.

- Turn students into content creators by mashing digital content with reading, writing, speaking and listening. Good readers write; good writers read. In the real world, reading, writing, speaking and listening are integrated. How do we help students learn this? Engage them in creating projects that use published digital content that is integrated with pieces they write, pictures they draw, audio or video recordings they make, etc. Troy Hicks, author of Digital Writing, Digital Teaching , calls this a “Mash-up.” These types of student content creations use all kinds of traditional literacies, but also a variety of new literacies like visual literacy, digital literacy, and information literacy.

No matter how much our technology changes our world, teaching our students to read and write will always be paramount to their future success. Processes will change; tools will change; and yes, even books will change. However, students will always need to read, write, speak, and listen. So, I encourage educators everywhere to begin to use digital content to prepare students for “new” literacies. Our students are depending on you to do so!

eSchool Media uses cookies to improve your experience. Visit our Privacy Policy for more information.

How Does Writing Fit Into the ‘Science of Reading’?

- Share article

In one sense, the national conversation about what it will take to make sure all children become strong readers has been wildly successful: States are passing legislation supporting evidence-based teaching approaches , and school districts are rushing to supply training. Publishers are under pressure to drop older materials . And for the first time in years, an instructional issue—reading—is headlining education media coverage.

In the middle of all that, though, the focus on the “science of reading” has elided its twin component in literacy instruction: writing.

Writing is intrinsically important for all students to learn—after all, it is the primary way beyond speech that humans communicate. But more than that, research suggests that teaching students to write in an integrated fashion with reading is not only efficient, it’s effective.

Yet writing is often underplayed in the elementary grades. Too often, it is separated from schools’ reading block. Writing is not assessed as frequently as reading, and principals, worried about reading-exam scores, direct teachers to focus on one often at the expense of the other. Finally, beyond the English/language arts block, kids often aren’t asked to do much writing in early grades.

“Sometimes, in an early-literacy classroom, you’ll hear a teacher say, ‘It’s time to pick up your pencils,’” said Wiley Blevins, an author and literacy consultant who provides training in schools. “But your pencils should be in your hand almost the entire morning.”

Strikingly, many of the critiques that reading researchers have made against the “balanced literacy” approach that has held sway in schools for decades could equally apply to writing instruction: Foundational writing skills—like phonics and language structure—have not generally been taught systematically or explicitly.

And like the “find the main idea” strategies commonly taught in reading comprehension, writing instruction has tended to focus on content-neutral tasks, rather than deepening students’ connections to the content they learn.

Education Week wants to bring more attention to these connections in the stories that make up this special collection . But first, we want to delve deeper into the case for including writing in every step of the elementary curriculum.

Why has writing been missing from the reading conversation?

Much like the body of knowledge on how children learn to read words, it is also settled science that reading and writing draw on shared knowledge, even though they have traditionally been segmented in instruction.

“The body of research is substantial in both number of studies and quality of studies. There’s no question that reading and writing share a lot of real estate, they depend on a lot of the same knowledge and skills,” said Timothy Shanahan, an emeritus professor of education at the University of Illinois Chicago. “Pick your spot: text structure, vocabulary, sound-symbol relationships, ‘world knowledge.’”

The reasons for the bifurcation in reading and writing are legion. One is that the two fields have typically been studied separately. (Researchers studying writing usually didn’t examine whether a writing intervention, for instance, also aided students’ reading abilities—and vice versa.)

Some scholars also finger the dominance of the federally commissioned National Reading Panel report, which in 2000 outlined key instructional components of learning to read. The review didn’t examine the connection of writing to reading.

Looking even further back yields insights, too. Penmanship and spelling were historically the only parts of writing that were taught, and when writing reappeared in the latter half of the 20th century, it tended to focus on “process writing,” emphasizing personal experience and story generation over other genres. Only when the Common Core State Standards appeared in 2010 did the emphasis shift to writing about nonfiction texts and across subjects—the idea that students should be writing about what they’ve learned.

And finally, teaching writing is hard. Few studies document what preparation teachers receive to teach writing, but in surveys, many teachers say they received little training in their college education courses. That’s probably why only a little over half of teachers, in one 2016 survey, said that they enjoyed teaching writing.

Writing should begin in the early grades

These factors all work against what is probably the most important conclusion from the research over the last few decades: Students in the early-elementary grades need lots of varied opportunities to write.

“Students need support in their writing,” said Dana Robertson, an associate professor of reading and literacy education at the school of education at Virginia Tech who also studies how instructional change takes root in schools. “They need to be taught explicitly the skills and strategies of writing and they need to see the connections of reading, writing, and knowledge development.”

While research supports some fundamental tenets of writing instruction—that it should be structured, for instance, and involve drafting and revising—it hasn’t yet pointed to a specific teaching recipe that works best.

One of the challenges, the researchers note, is that while reading curricula have improved over the years, they still don’t typically provide many supports for students—or teachers, for that matter—for writing. Teachers often have to supplement with additions that don’t always mesh well with their core, grade-level content instruction.

“We have a lot of activities in writing we know are good,” Shanahan said. “We don’t really have a yearlong elementary-school-level curriculum in writing. That just doesn’t exist the way it does in reading.”

Nevertheless, practitioners like Blevins work writing into every reading lesson, even in the earliest grades. And all the components that make up a solid reading program can be enhanced through writing activities.

4 Key Things to Know About How Reading and Writing Interlock

Want a quick summary of what research tells us about the instructional connections between reading and writing?

1. Reading and writing are intimately connected.

Research on the connections began in the early 1980s and has grown more robust with time.

Among the newest and most important additions are three research syntheses conducted by Steve Graham, a professor at the University of Arizona, and his research partners. One of them examined whether writing instruction also led to improvements in students’ reading ability; a second examined the inverse question. Both found significant positive effects for reading and writing.

A third meta-analysis gets one step closer to classroom instruction. Graham and partners examined 47 studies of instructional programs that balanced both reading and writing—no program could feature more than 60 percent of one or the other. The results showed generally positive effects on both reading and writing measures.

2. Writing matters even at the earliest grades, when students are learning to read.

Studies show that the prewriting students do in early education carries meaningful signals about their decoding, spelling, and reading comprehension later on. Reading experts say that students should be supported in writing almost as soon as they begin reading, and evidence suggests that both spelling and handwriting are connected to the ability to connect speech to print and to oral language development.

3. Like reading, writing must be taught explicitly.

Writing is a complex task that demands much of students’ cognitive resources. Researchers generally agree that writing must be explicitly taught—rather than left up to students to “figure out” the rules on their own.

There isn’t as much research about how precisely to do this. One 2019 review, in fact, found significant overlap among the dozen writing programs studied, and concluded that all showed signs of boosting learning. Debates abound about the amount of structure students need and in what sequence, such as whether they need to master sentence construction before moving onto paragraphs and lengthier texts.

But in general, students should be guided on how to construct sentences and paragraphs, and they should have access to models and exemplars, the research suggests. They also need to understand the iterative nature of writing, including how to draft and revise.

A number of different writing frameworks incorporating various degrees of structure and modeling are available, though most of them have not been studied empirically.

4. Writing can help students learn content—and make sense of it.

Much of reading comprehension depends on helping students absorb “world knowledge”—think arts, ancient cultures, literature, and science—so that they can make sense of increasingly sophisticated texts and ideas as their reading improves. Writing can enhance students’ content learning, too, and should be emphasized rather than taking a back seat to the more commonly taught stories and personal reflections.

Graham and colleagues conducted another meta-analysis of nearly 60 studies looking at this idea of “writing to learn” in mathematics, science, and social studies. The studies included a mix of higher-order assignments, like analyses and argumentative writing, and lower-level ones, like summarizing and explaining. The study found that across all three disciplines, writing about the content improved student learning.

If students are doing work on phonemic awareness—the ability to recognize sounds—they shouldn’t merely manipulate sounds orally; they can put them on the page using letters. If students are learning how to decode, they can also encode—record written letters and words while they say the sounds out loud.

And students can write as they begin learning about language structure. When Blevins’ students are mainly working with decodable texts with controlled vocabularies, writing can support their knowledge about how texts and narratives work: how sentences are put together and how they can be pulled apart and reconstructed. Teachers can prompt them in these tasks, asking them to rephrase a sentence as a question, split up two sentences, or combine them.

“Young kids are writing these mile-long sentences that become second nature. We set a higher bar, and they are fully capable of doing it. We can demystify a bit some of that complex text if we develop early on how to talk about sentences—how they’re created, how they’re joined,” Blevins said. “There are all these things you can do that are helpful to develop an understanding of how sentences work and to get lots of practice.”

As students progress through the elementary grades, this structured work grows more sophisticated. They need to be taught both sentence and paragraph structure , and they need to learn how different writing purposes and genres—narrative, persuasive, analytical—demand different approaches. Most of all, the research indicates, students need opportunities to write at length often.

Using writing to support students’ exploration of content

Reading is far more than foundational skills, of course. It means introducing students to rich content and the specialized vocabulary in each discipline and then ensuring that they read, discuss, analyze, and write about those ideas. The work to systematically build students’ knowledge begins in the early grades and progresses throughout their K-12 experience.

Here again, available evidence suggests that writing can be a useful tool to help students explore, deepen, and draw connections in this content. With the proper supports, writing can be a method for students to retell and analyze what they’ve learned in discussions of content and literature throughout the school day —in addition to their creative writing.

This “writing to learn” approach need not wait for students to master foundational skills. In the K-2 grades especially, much content is learned through teacher read-alouds and conversation that include more complex vocabulary and ideas than the texts students are capable of reading. But that should not preclude students from writing about this content, experts say.

“We do a read-aloud or a media piece and we write about what we learned. It’s just a part of how you’re responding, or sharing, what you’ve learned across texts; it’s not a separate thing from reading,” Blevins said. “If I am doing read-alouds on a concept—on animal habitats, for example—my decodable texts will be on animals. And students are able to include some of these more sophisticated ideas and language in their writing, because we’ve elevated the conversations around these texts.”

In this set of stories , Education Week examines the connections between elementary-level reading and writing in three areas— encoding , language and text structure , and content-area learning . But there are so many more examples.

Please write us to share yours when you’ve finished.

Want to read more about the research that informed this story? Here’s a bibliography to start you off.