How to Write a Poem, Step-by-Step

Sean Glatch | May 2, 2024 | 37 Comments

To learn how to write a poem step-by-step, let’s start where all poets start: the basics.

This article is an in-depth introduction to how to write a poem. We first answer the question, “What is poetry?” We then discuss the literary elements of poetry, and showcase some different approaches to the writing process—including our own seven-step process on how to write a poem step by step.

So, how do you write a poem? Let’s start with what poetry is.

How to Write a Poem: Contents

What Poetry Is

- Literary Devices

How to Write a Poem, in 7 Steps

How to write a poem: different approaches and philosophies.

- Okay, I Know How to Write a Good Poem. What Next?

It’s important to know what poetry is—and isn’t—before we discuss how to write a poem. The following quote defines poetry nicely:

“Poetry is language at its most distilled and most powerful.” —Former US Poet Laureate Rita Dove

Poetry Conveys Feeling

People sometimes imagine poetry as stuffy, abstract, and difficult to understand. Some poetry may be this way, but in reality poetry isn’t about being obscure or confusing. Poetry is a lyrical, emotive method of self-expression, using the elements of poetry to highlight feelings and ideas.

A poem should make the reader feel something.

In other words, a poem should make the reader feel something—not by telling them what to feel, but by evoking feeling directly.

Here’s a contemporary poem that, despite its simplicity (or perhaps because of its simplicity), conveys heartfelt emotion.

Poem by Langston Hughes

I loved my friend. He went away from me. There’s nothing more to say. The poem ends, Soft as it began— I loved my friend.

Poetry is Language at its Richest and Most Condensed

Unlike longer prose writing (such as a short story, memoir, or novel), poetry needs to impact the reader in the richest and most condensed way possible. Here’s a famous quote that enforces that distinction:

“Prose: words in their best order; poetry: the best words in the best order.” —Samuel Taylor Coleridge

So poetry isn’t the place to be filling in long backstories or doing leisurely scene-setting. In poetry, every single word carries maximum impact.

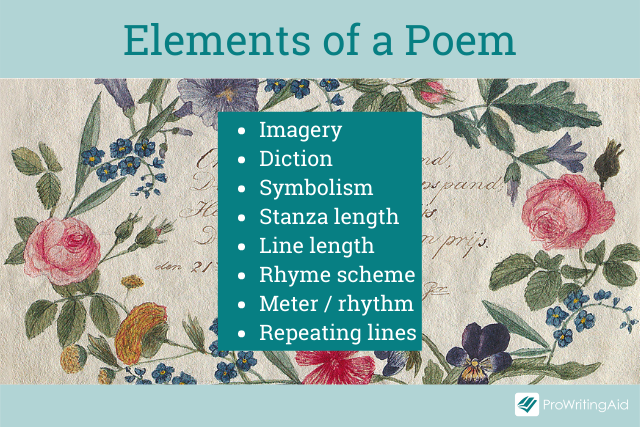

Poetry Uses Unique Elements

Poetry is not like other kinds of writing: it has its own unique forms, tools, and principles. Together, these elements of poetry help it to powerfully impact the reader in only a few words.

The elements of poetry help it to powerfully impact the reader in only a few words.

Most poetry is written in verse , rather than prose . This means that it uses line breaks, alongside rhythm or meter, to convey something to the reader. Rather than letting the text break at the end of the page (as prose does), verse emphasizes language through line breaks.

Poetry further accentuates its use of language through rhyme and meter. Poetry has a heightened emphasis on the musicality of language itself: its sounds and rhythms, and the feelings they carry.

These devices—rhyme, meter, and line breaks—are just a few of the essential elements of poetry, which we’ll explore in more depth now.

Understanding the Elements of Poetry

As we explore how to write a poem step by step, these three major literary elements of poetry should sit in the back of your mind:

- Rhythm (Sound, Rhyme, and Meter)

1. Elements of Poetry: Rhythm

“Rhythm” refers to the lyrical, sonic qualities of the poem. How does the poem move and breathe; how does it feel on the tongue?

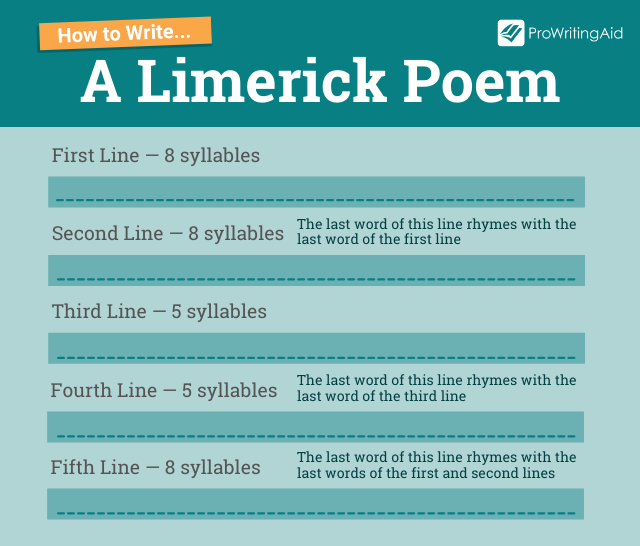

Traditionally, poets relied on rhyme and meter to accomplish a rhythmically sound poem. Free verse poems —which are poems that don’t require a specific length, rhyme scheme, or meter—only became popular in the West in the 20th century, so while rhyme and meter aren’t requirements of modern poetry, they are required of certain poetry forms.

Poetry is capable of evoking certain emotions based solely on the sounds it uses. Words can sound sinister, percussive, fluid, cheerful, dour, or any other noise/emotion in the complex tapestry of human feeling.

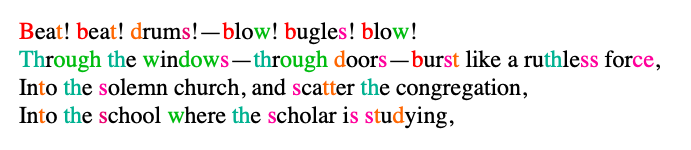

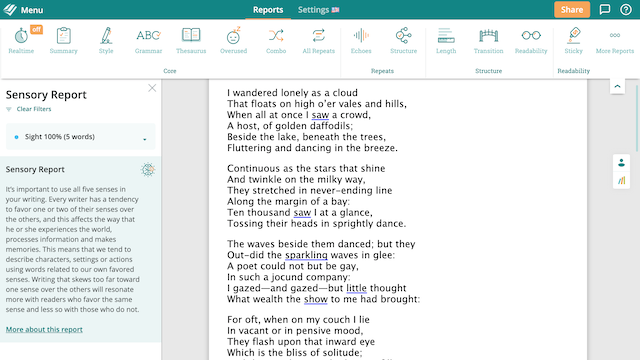

Take, for example, this excerpt from the poem “Beat! Beat! Drums!” by Walt Whitman:

Red — “b” sounds

Blue — “th” sounds

Green — “w” and “ew” sounds

Purple — “s” sounds

Orange — “d” and “t” sounds

This poem has a lot of percussive, disruptive sounds that reinforce the beating of the drums. The “b,” “d,” “w,” and “t” sounds resemble these drum beats, while the “th” and “s” sounds are sneakier, penetrating a deeper part of the ear. The cacophony of this excerpt might not sound “lyrical,” but it does manage to command your attention, much like drums beating through a city might sound.

To learn more about consonance and assonance, euphony and cacophony, onomatopoeia , and the other uses of sound, take a look at our article “12 Literary Devices in Poetry.”

https://writers.com/literary-devices-in-poetry

It would be a crime if you weren’t primed on the ins and outs of rhymes. “Rhyme” refers to words that have similar pronunciations, like this set of words: sound, hound, browned, pound, found, around.

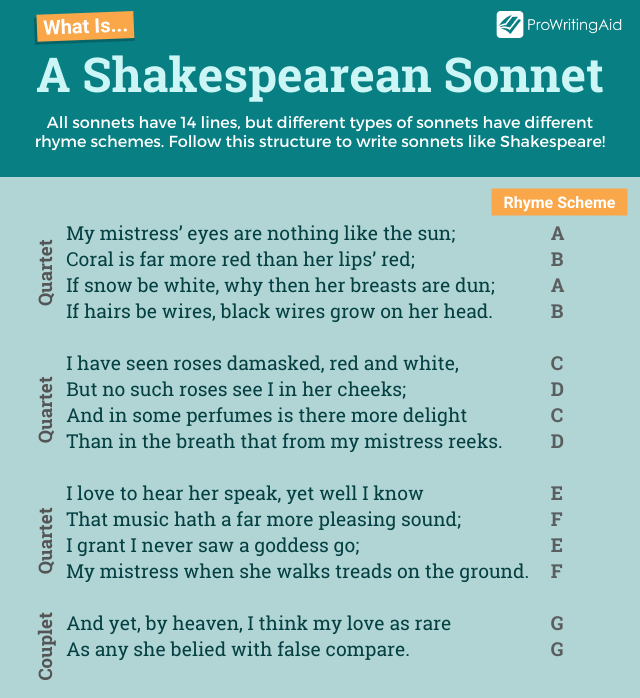

Many poets assume that their poetry has to rhyme, and it’s true that some poems require a complex rhyme scheme. However, rhyme isn’t nearly as important to poetry as it used to be. Most traditional poetry forms—sonnets, villanelles , rimes royal, etc.—rely on rhyme, but contemporary poetry has largely strayed from the strict rhyme schemes of yesterday.

There are three types of rhymes:

- Homophony: Homophones are words that are spelled differently but sound the same, like “tail” and “tale.” Homophones often lead to commonly misspelled words .

- Perfect Rhyme: Perfect rhymes are word pairs that are identical in sound except for one minor difference. Examples include “slant and pant,” “great and fate,” and “shower and power.”

- Slant Rhyme: Slant rhymes are word pairs that use the same sounds, but their final vowels have different pronunciations. For example, “abut” and “about” are nearly-identical in sound, but are pronounced differently enough that they don’t completely rhyme. This is also known as an oblique rhyme or imperfect rhyme.

Meter refers to the stress patterns of words. Certain poetry forms require that the words in the poem follow a certain stress pattern, meaning some syllables are stressed and others are unstressed.

What is “stressed” and “unstressed”? A stressed syllable is the sound that you emphasize in a word. The bolded syllables in the following words are stressed, and the unbolded syllables are unstressed:

- Un• stressed

- Plat• i• tud• i•nous

- De •act•i• vate

- Con• sti •tu• tion•al

The pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables is important to traditional poetry forms. This chart, copied from our article on form in poetry , summarizes the different stress patterns of poetry.

| Meter | Pattern | Example |

| Iamb | Unstressed–stressed | Ex |

| Trochee | Stressed–unstressed | ple |

| Pyrrh | Equally unstressed | Pyrrhic |

| Spondee | Equally stressed | |

| Dactyl | Stressed–unstressed–unstressed | ener |

| Anapest | Unstressed–unstressed–stressed | Compre |

| Amphibrach (rare) | Unstressed–stressed–unstressed | Fla go |

2. Elements of Poetry: Form

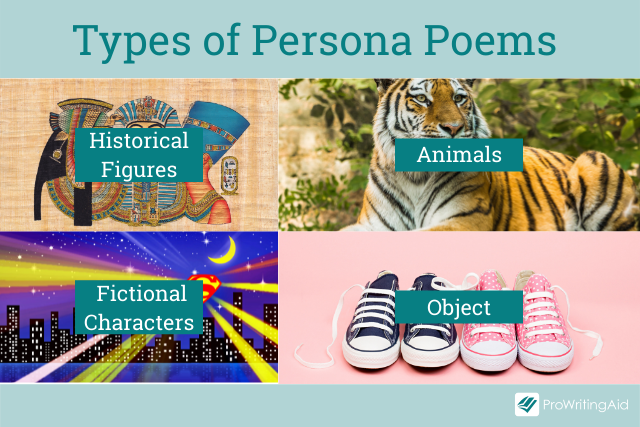

“Form” refers to the structure of the poem. Is the poem a sonnet , a villanelle, a free verse piece, a slam poem, a contrapuntal, a ghazal , a blackout poem , or something new and experimental?

Form also refers to the line breaks and stanza breaks in a poem. Unlike prose, where the end of the page decides the line breaks, poets have control over when one line ends and a new one begins. The words that begin and end each line will emphasize the sounds, images, and ideas that are important to the poet.

To learn more about rhyme, meter, and poetry forms, read our full article on the topic:

https://writers.com/what-is-form-in-poetry

3. Elements of Poetry: Literary Devices

“Poetry: the best words in the best order.” — Samuel Taylor Coleridge

How does poetry express complex ideas in concise, lyrical language? Literary devices—like metaphor, symbolism , juxtaposition , irony , and hyperbole—help make poetry possible. Learn how to write and master these devices here:

https://writers.com/common-literary-devices

To condense the elements of poetry into an actual poem, we’re going to follow a seven-step approach. However, it’s important to know that every poet’s process is different. While the steps presented here are a logical path to get from idea to finished poem, they’re not the only tried-and-true method of poetry writing. Poets can—and should!—modify these steps and generate their own writing process.

Nonetheless, if you’re new to writing poetry or want to explore a different writing process, try your hand at our approach. Here’s how to write a poem step by step!

1. Devise a Topic

The easiest way to start writing a poem is to begin with a topic.

However, devising a topic is often the hardest part. What should your poem be about? And where can you find ideas?

Here are a few places to search for inspiration:

- Other Works of Literature: Poetry doesn’t exist in a vacuum—it’s part of a larger literary tapestry, and can absolutely be influenced by other works. For example, read “The Golden Shovel” by Terrance Hayes , a poem that was inspired by Gwendolyn Brooks’ “We Real Cool.”

- Real-World Events: Poetry, especially contemporary poetry, has the power to convey new and transformative ideas about the world. Take the poem “A Cigarette” by Ilya Kaminsky , which finds community in a warzone like the eye of a hurricane.

- Your Life: What would poetry be if not a form of memoir? Many contemporary poets have documented their lives in verse. Take Sylvia Plath’s poem “Full Fathom Five” —a daring poem for its time, as few writers so boldly criticized their family as Plath did.

- The Everyday and Mundane: Poetry isn’t just about big, earth-shattering events: much can be said about mundane events, too. Take “Ode to Shea Butter” by Angel Nafis , a poem that celebrates the beautiful “everydayness” of moisturizing.

- Nature: The Earth has always been a source of inspiration for poets, both today and in antiquity. Take “Wild Geese” by Mary Oliver , which finds meaning in nature’s quiet rituals.

- Writing Exercises: Prompts and exercises can help spark your creativity, even if the poem you write has nothing to do with the prompt! Here’s 24 writing exercises to get you started.

At this point, you’ve got a topic for your poem. Maybe it’s a topic you’re passionate about, and the words pour from your pen and align themselves into a perfect sonnet! It’s not impossible—most poets have a couple of poems that seemed to write themselves.

However, it’s far more likely you’re searching for the words to talk about this topic. This is where journaling comes in.

Sit in front of a blank piece of paper, with nothing but the topic written on the top. Set a timer for 15-30 minutes and put down all of your thoughts related to the topic. Don’t stop and think for too long, and try not to obsess over finding the right words: what matters here is emotion, the way your subconscious grapples with the topic.

At the end of this journaling session, go back through everything you wrote, and highlight whatever seems important to you: well-written phrases, poignant moments of emotion, even specific words that you want to use in your poem.

Journaling is a low-risk way of exploring your topic without feeling pressured to make it sound poetic. “Sounding poetic” will only leave you with empty language: your journal allows you to speak from the heart. Everything you need for your poem is already inside of you, the journaling process just helps bring it out!

Learn more about keeping a daily journal here:

How to Start Journaling: Practical Advice on How to Journal Daily

3. Think About Form

As one of the elements of poetry, form plays a crucial role in how the poem is both written and read. Have you ever wanted to write a sestina ? How about a contrapuntal, or a double cinquain, or a series of tanka? Your poem can take a multitude of forms, including the beautifully unstructured free verse form; while form can be decided in the editing process, it doesn’t hurt to think about it now.

4. Write the First Line

After a productive journaling session, you’ll be much more acquainted with the state of your heart. You might have a line in your journal that you really want to begin with, or you might want to start fresh and refer back to your journal when you need to! Either way, it’s time to begin.

What should the first line of your poem be? There’s no strict rule here—you don’t have to start your poem with a certain image or literary device. However, here’s a few ways that poets often begin their work:

- Set the Scene: Poetry can tell stories just like prose does. Anne Carson does just this in her poem “Lines,” situating the scene in a conversation with the speaker’s mother.

- Start at the Conflict : Right away, tell the reader where it hurts most. Margaret Atwood does this in “Ghost Cat,” a poem about aging.

- Start With a Contradiction: Juxtaposition and contrast are two powerful tools in the poet’s toolkit. Joan Larkin’s poem “Want” begins and ends with these devices. Carlos Gimenez Smith also begins his poem “Entanglement” with a juxtaposition.

- Start With Your Title: Some poets will use the title as their first line, like Ron Padgett’s poem “Ladies and Gentlemen in Outer Space.”

There are many other ways to begin poems, so play around with different literary devices, and when you’re stuck, turn to other poetry for inspiration.

5. Develop Ideas and Devices

You might not know where your poem is going until you finish writing it. In the meantime, stick to your literary devices. Avoid using too many abstract nouns, develop striking images, use metaphors and similes to strike interesting comparisons, and above all, speak from the heart.

6. Write the Closing Line

Some poems end “full circle,” meaning that the images the poet used in the beginning are reintroduced at the end. Gwendolyn Brooks does this in her poem “my dreams, my work, must wait till after hell.”

Yet, many poets don’t realize what their poems are about until they write the ending line . Poetry is a search for truth, especially the hard truths that aren’t easily explained in casual speech. Your poem, too, might not be finished until it comes across a necessary truth, so write until you strike the heart of what you feel, and the poem will come to its own conclusion.

7. Edit, Edit, Edit!

Do you have a working first draft of your poem? Congratulations! Getting your feelings onto the page is a feat in itself.

Yet, no guide on how to write a poem is complete without a note on editing. If you plan on sharing or publishing your work, or if you simply want to edit your poem to near-perfection, keep these tips in mind.

- Adjectives and Adverbs: Use these parts of speech sparingly. Most imagery shouldn’t rely on adjectives and adverbs, because the image should be striking and vivid on its own, without too much help from excess language.

- Concrete Line Breaks: Line breaks help emphasize important words, making certain images and themes clearer to the reader. As a general rule, most of your lines should start and end with concrete words—nouns and verbs especially.

- Stanza Breaks: Stanzas are like paragraphs to poetry. A stanza can develop a new idea, contrast an existing idea, or signal a transition in the poem’s tone. Make sure each stanza clearly stands for something as a unit of the poem.

- Mixed Metaphors: A mixed metaphor is when two metaphors occupy the same idea, making the poem unnecessarily difficult to understand. Here’s an example of a mixed metaphor: “a watched clock never boils.” The meaning can be discerned, but the image remains unclear. Be wary of mixed metaphors—though some poets (like Shakespeare) make them work, they’re tricky and often disruptive.

- Abstractions: Above all, avoid using excessively abstract language. It’s fine to use the word “love” 2 or 3 times in a poem, but don’t use it twice in every stanza. Let the imagery in your poem express your feelings and ideas, and only use abstractions as brief connective tissue in otherwise-concrete writing.

Lastly, don’t feel pressured to “do something” with your poem. Not all poems need to be shared and edited. Poetry doesn’t have to be “good,” either—it can simply be a statement of emotions by the poet, for the poet. Publishing is an admirable goal, but also, give yourself permission to write bad poems, unedited poems, abstract poems, and poems with an audience of one. Write for yourself—editing is for the other readers.

Poetry is the oldest literary form, pre-dating prose, theater, and the written word itself. As such, there are many different schools of thought when it comes to writing poetry. You might be wondering how to write a poem through different methods and approaches: here’s four philosophies to get you started.

How to Write a Poem: Poetry as Emotion

If you asked a Romantic Poet “what is poetry?”, they would tell you that poetry is the spontaneous emotion of the soul.

The Romantic Era viewed poetry as an extension of human emotion—a way of perceiving the world through unbridled creativity, centered around the human soul. While many Romantic poets used traditional forms in their poetry, the Romantics weren’t afraid to break from tradition, either.

To write like a Romantic, feel—and feel intensely. The words will follow the emotions, as long as a blank page sits in front of you.

How to Write a Poem: Poetry as Stream of Consciousness

If you asked a Modernist poet, “What is poetry?” they would tell you that poetry is the search for complex truths.

Modernist Poets were keen on the use of poetry as a window into the mind. A common technique of the time was “Stream of Consciousness,” which is unfiltered writing that flows directly from the poet’s inner dialogue. By tapping into one’s subconscious, the poet might uncover deeper truths and emotions they were initially unaware of.

Depending on who you are as a writer, Stream of Consciousness can be tricky to master, but this guide covers the basics of how to write using this technique.

How to Write a Poem: Mindfulness

Mindfulness is a practice of documenting the mind, rather than trying to control or edit what it produces. This practice was popularized by the Beat Poets , who in turn were inspired by Eastern philosophies and Buddhist teachings. If you asked a Beat Poet “what is poetry?”, they would tell you that poetry is the human consciousness, unadulterated.

To learn more about the art of leaving your mind alone , take a look at our guide on Mindfulness, from instructor Marc Olmsted.

https://writers.com/mindful-writing

How to Write a Poem: Poem as Camera Lens

Many contemporary poets use poetry as a camera lens, documenting global events and commenting on both politics and injustice. If you find yourself itching to write poetry about the modern day, press your thumb against the pulse of the world and write what you feel.

Additionally, check out these two essays by Electric Literature on the politics of poetry:

- What Can Poetry Do That Politics Can’t?

- Why All Poems Are Political (TL;DR: Poetry is an urgent expression of freedom).

Okay, I Know How to Write a Poem. What Next?

Poetry, like all art forms, takes practice and dedication. You might write a poem you enjoy now, and think it’s awfully written 3 years from now; you might also write some of your best work after reading this guide. Poetry is fickle, but the pen lasts forever, so write poems as long as you can!

Once you understand how to write a poem, and after you’ve drafted some pieces that you’re proud of and ready to share, here are some next steps you can take.

Publish in Literary Journals

Want to see your name in print? These literary journals house some of the best poetry being published today.

https://writers.com/best-places-submit-poetry-online

Assemble and Publish a Manuscript

A poem can tell a story. So can a collection of poems. If you’re interested in publishing a poetry book, learn how to compose and format one here:

https://writers.com/poetry-manuscript-format

How to Write a Poem: Join a Writing Community

Writers.com is an online community of writers, and we’d love it if you shared your poetry with us! Join us on Facebook and check out our upcoming poetry courses .

Poetry doesn’t exist in a vacuum, it exists to educate and uplift society. The world is waiting for your voice, so find a group and share your work!

Sean Glatch

37 comments.

super useful! love these articles 💕

Finally found a helpful guide on Poetry’. For many year, I have written and filed numerous inspired pieces from experiences and moment’s of epiphany. Finally, looking forward to convertinb to ‘poetry format’. THANK YOU, KINDLY. 🙏🏾

Indeed, very helpful, consize. I could not say more than thank you.

I’ve never read a better guide on how to write poetry step by step. Not only does it give great tips, but it also provides helpful links! Thank you so much.

Thank you very much, Hamna! I’m so glad this guide was helpful for you.

Best guide so far

Very inspirational and marvelous tips

Thank you super tips very helpful.

I have never gone through the steps of writing poetry like this, I will take a closer look at your post.

Beautiful! Thank you! I’m really excited to try journaling as a starter step x

[…] How to Write a Poem, Step-by-Step […]

This is really helpful, thanks so much

Extremely thorough! Nice job.

Thank you so much for sharing your awesome tips for beginner writers!

People must reboot this and bookmark it. Your writing and explanation is detailed to the core. Thanks for helping me understand different poetic elements. While reading, actually, I start thinking about how my husband construct his songs and why other artists lack that organization (or desire to be better). Anyway, this gave me clarity.

I’m starting to use poetry as an outlet for my blogs, but I also have to keep in mind I’m transitioning from a blogger to a poetic sweet kitty potato (ha). It’s a unique transition, but I’m so used to writing a lot, it’s strange to see an open blog post with a lot of lines and few paragraphs.

Anyway, thanks again!

I’m happy this article was so helpful, Eternity! Thanks for commenting, and best of luck with your poetry blog.

Yours in verse, Sean

One of the best articles I read on how to write poems. And it is totally step by step process which is easy to read and understand.

Thanks for the step step explanation in how to write poems it’s a very helpful to me and also for everyone one. THANKYOU

Totally detailed and in a simple language told the best way how to write poems. It is a guide that one should read and follow. It gives the detailed guidance about how to write poems. One of the best articles written on how to write poems.

what a guidance thank you so much now i can write a poem thank you again again and again

The most inspirational and informative article I have ever read in the 21st century.It gives the most relevent,practical, comprehensive and effective insights and guides to aspiring writers.

Thank you so much. This is so useful to me a poetry

[…] Write a short story/poem (Here are some tips) […]

It was very helpful and am willing to try it out for my writing Thanks ❤️

Thank you so much. This is so helpful to me, and am willing to try it out for my writing .

Absolutely constructive, direct, and so useful as I’m striving to develop a recent piece. Thank you!

thank you for your explanation……,love it

Really great. Nothing less.

I can’t thank you enough for this, it touched my heart, this was such an encouraging article and I thank you deeply from my heart, I needed to read this.

great teaching Did not know all that in poetry writing

This was very useful! Thank you for writing this.

After reading a Charles Bukowski poem, “My Cats,” I found you piece here after doing a search on poetry writing format. Your article is wonderful as is your side article on journaling. I want to dig into both and give it another go another after writing poetry when I was at university. Thank you!

Thanks for reading, Vicki! Let us know how we can support your writing journey. 🙂

Thank you for the nice and informative post. This article truly offers a lot more details about this topic.

Very useful information. I’m glad to see you discussed rhyming, too. I was in the perhaps mistaken idea that rhyming is frowned upon in contemporary poems.

Thanks alot this highly needed for a starter like me

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

VIDEO COURSE

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Sign up now to watch a free lesson!

Learn How to Write a Novel

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Enroll now for daily lessons, weekly critique, and live events. Your first lesson is free!

Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Nov 23, 2022

How to Write a Poem: Get Tips from a Published Poet

Ever wondered how to write a poem? For writers who want to dig deep, composing verse lets you sift the sand of your experience for new glimmers of insight. And if you’re in it for less lofty reasons, shaping a stanza from start to finish can teach you to have fun with language in totally new ways.

To help demystify the subtle art of writing verse, we chatted with Reedsy editor (and published poet) Lauren Stroh . In 8 simple steps, here's how to write a poem:

1. Brainstorm your starting point

2. free-write in prose first, 3. choose your poem’s form and style, 4. read for inspiration, 5. write for an audience of one — you, 6. read your poem out loud, 7. take a break to refresh your mind, 8. have fun revising your poem.

If you’re struggling to write your poem in order from the first line to the last, a good trick is opening with whichever starting point your brain can latch onto as it learns to think in verse.

Your starting point can be a line or a phrase you want to work into your poem, though it doesn’t have to take the form of language at all. It might be a picture in your head, as particular as the curl of hair over your daughter’s ear as she sleeps, or as capacious as the sea. It can even be a complicated feeling you want to render with precision — or maybe it's a memory you return to again and again. Think of this starting point as the "why" behind your poem, your impetus for writing it in the first place.

If you’re worried your starting point isn’t grand enough to merit an entire poem, stop right there. After all, literary giants have wrung verse out of every topic under the sun, from the disappointments of a post- Odyssey Odysseus to illicitly eaten refrigerated plums .

As Lauren Stroh sees it, your experience is more than worthy of being immortalized in verse.

"I think the most successful poems articulate something true about the human experience and help us look at the everyday world in new and exciting ways."

It may seem counterintuitive but if you struggle to write down lines that resonate, perhaps start with some prose writing first. Take this time to delve into the image, feeling, or theme at the heart of your poem, and learn to pin it down with language. Give yourself a chance to mull things over before actually writing the poem.

Take 10 minutes and jot down anything that comes to mind when you think of your starting point. You can write in paragraphs, dash off bullet points, or even sketch out a mind map . The purpose of this exercise isn’t to produce an outline: it’s to generate a trove of raw material, a repertoire of loosely connected fragments to draw upon as you draft your poem in earnest.

Silence your inner critic for now

And since this is raw material, the last thing you should do is censor yourself. Catch yourself scoffing at a turn of phrase, overthinking a rhetorical device , or mentally grousing, “This metaphor will never make it into the final draft”? Tell that inner critic to hush for now and jot it down anyway. You just might be able to refine that slapdash, off-the-cuff idea into a sharp and poignant line.

Whether you’ve free-written your way to a beginning or you’ve got a couple of lines jotted down, before you complete a whole first draft of your poem, take some time to think about form and style.

The form of a poem often carries a lot of meaning beyond the structural "rules" that it offers the writer. The rhyme patterns of sonnets — and the Shakespearean influence over the form — usually lend themselves to passionate pronouncements of love, whether merry or bleak. On the other hand, acrostic poems are often more cheeky because of the secret meaning that it hides in plain sight.

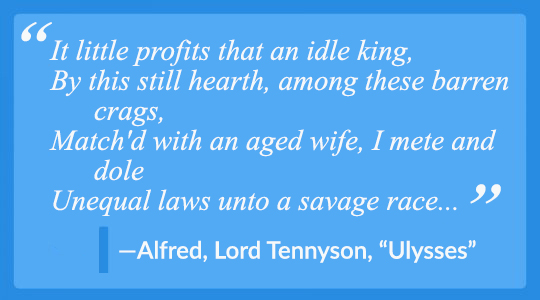

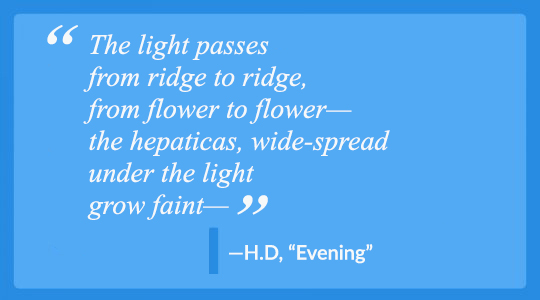

Even if your material begs for a poem without formal restrictions, you’ll still have to decide on the texture and tone of your language. Free verse, after all, is as diverse a form as the novel, ranging from the breathless maximalism of Walt Whitman to the cool austerity of H.D . Where, on this spectrum, will your poem fall?

Choosing a form and tone for your poem early on can help you work with some kind of structure to imbue more meanings to your lines. And if you’ve used free-writing to generate some raw material for yourself, a structure can give you the guidance you need to organize your notes into a poem.

A poem isn’t a nonfiction book or a historical novel: you don’t have to accumulate reams of research to write a good one. That said, a little bit of outside reading can stave off writer’s block and keep you inspired throughout the writing process.

Build a short, personalized syllabus around your poem’s form and subject. Say you’re writing a sensorily rich, linguistically spare bit of free verse about a relationship of mutual jealousy between mother and daughter. In that case, you’ll want to read some key Imagist poems , alongside some poems that sketch out complicated visions of parenthood in unsentimental terms.

And if you don’t want to limit yourself to poems similar in form and style to your own, Lauren has you covered with an all-purpose reading list:

- The Dream of a Common Languag e by Adrienne Rich

- Anything you can get your hands on by Mary Oliver

- The poems “ Failures in Infinitives ” and “ Fish & Chips ” by Bernadette Mayer.

- I often gift Lunch Poems by Frank O’Hara to friends who write.

- Everyone should read the interviews from the Paris Review’s archives . It’s just nice to observe how people familiar with language talk when they’re not performing, working, or warming up to write.

Even with preparation, the pressure of actually producing verse can still awaken your inner metrophobe (or poetry-fearer). What if people don’t understand — or even misinterpret — what you’re trying to say? What if they don’t feel drawn to your work? To keep the anxiety at bay, Lauren suggests writing for yourself, not for an external audience.

"I absolutely believe that poets can determine the validity of their own success if they are changed by the work they are producing themselves; if they are challenged by it; or if it calls into question their ethics, their habits, or their relationship to the living world. And personally, my life has certainly been changed by certain lines I’ve had the bravery to think and then write — and those moments are when I’ve felt most like I’ve made it."

You might eventually polish your work if you decide to publish your poetry down the line. (If you do, definitely check out the rest of this guide for tips and a list of magazines to submit to.) But as your first draft comes together, treat it like it’s meant for your eyes only.

A good poem doesn’t have to be pretty: maybe an easy, melodic loveliness isn’t your aim. It should, however, come alive on the page with a consciously crafted rhythm, whether hymn-like or discordant. To achieve that, read your poem out loud — at first, line by line, and then all together, as a complete text.

Trying out every line against your ear can help you weigh out a choice between synonyms — getting you to notice, say, the watery sound of “glacial”, the brittleness of “icy,” the solidity of “cold”.

Reading out loud can also help you troubleshoot line breaks that just don't feel right. Is the line unnaturally long, forcing you to rush through it or pause in the middle for a hurried inhale? If so, do you like that destabilizing effect, or do you want to literally give the reader some room to breathe? Testing these variations aloud is perhaps the only way to answer questions like these.

While it’s incredibly exciting to complete a draft of your poem, and you might be itching to dive back in and edit it, it’s always advisable to take a break first. You don’t have to turn completely away from writing if you don’t want to. Take a week to chip away at your novel or even muse idly on your next poetic project — so long as you distance yourself from this poem a little while.

This is because, by this point, you’ve probably read out every line so many times the meaning has leached out of the syllables. With the time away, you let your mind refresh so that you can approach the piece with sharper attention and more ideas to refine it.

At the end of the day, even if you write in a well-established form, poetry is about experimenting with language, both written and spoken. Lauren emphasizes that revising a poem is thus an open-ended process that requires patience — and a sense of play.

"Have fun. Play. Be patient. Don’t take it seriously, or do. Though poems may look shorter than what you’re used to writing, they often take years to be what they really are. They change and evolve. The most important thing is to find a quiet place where you can be with yourself and really listen."

Is it time to get other people involved?

Want another pair of eyes on your poem during this process? You have options. You can swap pieces with a beta reader , workshop it with a critique group , or even engage a professional poetry editor like Lauren to refine your work — a strong option if you plan to submit it to a journal or turn it into the foundation for a chapbook .

Want a poetry expert to polish up your verse?

Professional poetry editors are on Reedsy. Sign up for free to meet them!

Learn how Reedsy can help you craft a beautiful book.

The working poet's checklist

If you decide to fly solo, here’s a checklist to work through as you revise:

✅ Hunt for clichés. Did you find yourself reaching for ready-made idioms at any point? Go back to the sentiment you were grappling with and try to capture it in stronger, more vivid terms.

✅ See if your poem begins where it should. Did you take a few lines of throat-clearing to get to the actual point? Try starting your poem further down.

✅ Make sure every line belongs. As you read each line, ask yourself: how does this contribute to the poem as a whole? Does it advance the theme, clarify the imagery, set or subvert the reader’s expectations? If you answer with something like, “It makes the poem sound nice,” consider cutting it.

Once you’ve worked your way through this checklist, feel free to brew yourself a cup of tea and sit quietly for a while, reflecting on your literary triumphs.

Whether these poetry writing tips have awakened your inner Wordsworth, or sent you happily gamboling back to prose, we hope you enjoyed playing with poetry — and that you learned something new about your approach to language.

And if you are looking to share your poetry with the world, the next post in this guide can show the ropes regarding how to publish your poems!

Anna Clarke says:

29/03/2020 – 04:37

I entered a short story competition and though I did not medal, one of the judges told me that some of my prose is very poetic. The following year I entered a poetry competition and won a bronze medal. That was my first attempt at writing poetry. I am more aware of figurative language in writing prose now. I am learning to marry the two. I don't have any poems online.

Comments are currently closed.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

Free Course: Spark Creativity With Poetry

Learn to harness the magic of poetry and enhance your writing.

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

Promising Poetry

Find solace in reading, writing & gifting poetry

Starting from Scratch: A Beginner’s Guide to Writing Poetry

- 3 February 2023

Why poetry?

Where did i start, a path of creative self-expression, forget editing & go with the flow, show, not tell, write for one person, make it relatable, read it aloud, edit and evolve, trust the process.

I’m sure if you are reading this, at least for once you would have written poetry or attempted to write one. Whether a student, teacher, parent, someone from a literary background, homemaker or an uneducated person, everyone makes an effort to write a poem at some point in their lifetime. The simple reason behind this is that poetry is a means of self-expression, to capture emotions, thoughts, and experiences in a creative and imaginative way. Here’s a beginner’s guide to writing poetry from scratch.

Poetry can be used to tell a story, convey a message, evoke a feeling, or simply play with language. Writing poetry can also be a form of therapy, allowing people to work through difficult emotions and explore their inner selves. Additionally, poetry has been a significant part of human culture for thousands of years, passing down stories, beliefs, and traditions from one generation to the next.

So whatever your reason for writing poetry be, know that you are not alone and every expression matters. You don’t need a degree in literature or great writing skills to pen poetry. If you don’t believe me, let me tell you how I started writing one. It is a little embarrassing for me to put it here but then if it could help you see a possibility for your own poetry-writing journey, then why not, right?

When I was around 11 years old (that’s 23 years back) I started writing and my very first fascination was nature and it still remains to be so. My ‘idea’ of poetry at that time was just about lines ending with rhymes. This is how my very first poem, started (don’t laugh at it; it was a kid’s expression then!):

Do you see that? At this age, after years of writing experience, I can see so many things flawed in the above stanza. For one, it has to be God’s ‘creation’ & not ‘creature’ and the whole thing looks like a ‘forced rhyming’ just to call it poetry. Don’t even ask me about the rest of the stanzas. But wait, does it matter that it was flawed? Absolutely no; because I see it as a ‘start’.

Yes, that day, a small kid started her journey towards self-expression and all that mattered to her were words that helped her make sense of what was happening around her and also inside her mind. And my dear friend, that’s all that should matter to you too when you are starting to pen poetry.

Writing poetry is a path of creative self-expression.

Choose a theme that talks to you

Now that you know what really matters, let’s get to the act of writing. All you need is an intention to write one. Firstly, choose a theme that talks to you or tap into an emotion that you are currently experiencing. That way you can easily get into the flow of writing instead of getting about it mechanically. Start somewhere, anywhere but just start. It really doesn’t matter if you write a great starting line or not, trust me!

If you are still stuck wondering where to start, then simply borrow a line/phrase from any book you read or a poem you liked. You can later replace the first line with something of your own; it really works. And yeah, it is not copying, it’s simply taking inspiration.

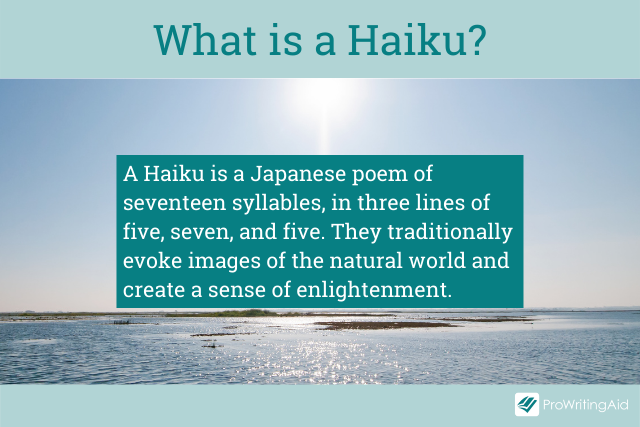

If you ask any of the writers or poets, they will tell you how most times their first drafts end up nothing but crap. So fret not about perfection and simply add one word after the other. Remember, just one word after the other. Easy, right? For beginners, free verse is the best bet but if you are in the mood for experimentation with different forms like haiku, lyrical poems, etc, then go for it. Just don’t let the structure restrict the flow of your ideas.

How To Write Better Poetry

Poetry is enriched with vivid imagery (descriptions). Showing and not telling is a writing technique used to create vivid and engaging descriptions by allowing readers to experience and interpret events and emotions, rather than just being told about them. All you need to do is to tap a little deeper into your sense of touch, vision, hearing, smell or taste. Here are some examples of showing and not telling:

- Telling: The food was delicious. Showing: The flavors exploded in his mouth as he savored each bite of the perfectly cooked biriyani.

- Telling: She was sad. Showing: Tears streamed down her cheeks as she sat alone, staring blankly out the window.

- Telling: The view was breathtaking. Showing: The sun set over the mountains, painting the sky in shades of pink and orange and taking his breath away.

Every individual has different perspectives and it’s the ability to put our perspectives out loud and clear that matters. So, loosen up, leave your hesitations and write for one person-yourself. Even if you plan to publish, it’s just you and the other person who is reading that is involved in this equation. So write for either yourself or just one reader. That way, the connection between you and the reader is easily established.

Have you noticed that a song lyrics appeals to you so much that it feels it was written just for you? Well, that’s where relatability comes into the picture. Even while you are writing your personal experiences, try and make it relatable to the reader.

To make a poem written from personal experience relatable to the reader, you can focus on universal themes and emotions that are common to many people. This can include topics such as love, loss, joy, fear, hope, etc. Additionally, you can use concrete and specific details that paint a vivid picture of your experiences and help the reader connect with them on an emotional level.

Avoid using jargon or uncommon terminology that may confuse or alienate the reader. Finally, you can use literary devices such as imagery, metaphor, and simile to enhance the emotional impact of the poem.

Reading your poem aloud can help you to identify and correct any issues in your writing, and to gain a better understanding of how the poem will be received by an audience. This is when you will get an idea of how the usage of words complement each other or not, whether is there a rhythmic flow to the poem, is the tone and theme of the poem are conveyed or not, etc.

So, own your poem and read it aloud to help you understand the nuances intuitively. It may sound difficult but try and see. You will get better at it with every poem.

Now that you know how your poetry has turned out and how it sounds while reading, it’s time that you make the edits and polish your poem. Though editing may take time to learn, it’s still your poem to experiment and evolve. Take charge of it and check the tone and mood of the poem. Make sure they match the content and the emotional impact you want to convey.

Read the poem several times, paying attention to each line and stanza. Look for areas that could be improved, such as awkward phrasing or unclear meaning. Consider using synonyms, metaphors, and similes to add depth and impact. Check the structure of the poem. Make sure each stanza and line break serves a purpose, and that the poem has a clear beginning, middle, and end. Finally, have someone else read the poem and provide feedback. This can give you a fresh perspective and help you to identify areas that could be improved.

Poetry is a creative form of self-expression. So, trust the process and evolve with each piece of writing. Also, poetry gives you the liberty to break the rules and simply have fun. So what stops you from writing a poetry, today? Get creative. Get bold. Get writing!

P.S. At the start of this post you read the childish poetry that I started with. To know how my writing has evolved over years, you can check these two poems (click on the below images) that are inspired by my all-time fascination with nature. You will see that with years, the experiences and perspectives have evolved. And, that is all that I wish for you to know, so you honour your expressions and emotions in verses without any hesitation.

How I Fell in Love With Her

If Only You Wake Up To Become the Sunlight

Hope this post helps. If you are just beginning to pen poetry, feel free to post it in the comments or share it on Twitter and tag me @PoetryPromising .

If you are an established poet, do share your very first piece of poetry. Let others be inspired.

Happy Poetrying!

2 Comments on Starting from Scratch: A Beginner’s Guide to Writing Poetry

- Pingback: #BlogchatterA2Z Theme Reveal: The Poet's Alphabet - Promising Poetry

- Pingback: Let's Create Poetry Together - #The100DayProject #CollaborativePoetry - Promising Poetry

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Yes, add me to your mailing list.

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

36 Poetry Writing Tips

by Melissa Donovan | Aug 10, 2023 | Poetry Writing | 72 comments

Poetry writing tips.

Poetry is the most artistic and liberating form of creative writing. You can write in the abstract or the concrete. Images can be vague or subtle, brilliant or dull. Write in form, using patterns, or write freely, letting your conscience (or subconscious) be your guide.

You can do just about anything in a poem. That’s why poetry writing is so wild and free; there are no rules. Poets have complete liberty to build something out of nothing simply by stringing words together.

All of this makes poetry writing alluring to writers who are burning with creativity. A poet’s process is magical and mesmerizing. But all that freedom and creativity can be a little overwhelming. If you can travel in any direction, which way should you go? Where are the guideposts?

Today’s writing tips include various tools and techniques that a poet can use. But these tips aren’t just for poets. All writers benefit from dabbling in poetry. Read a little poetry, write a few poems, study some basic concepts in poetry, and your other writing (fiction, creative nonfiction, even blogging) will soar.

Below, you’ll find thirty-six writing tips that take you on a little journey through the craft of poetry writing. See which ones appeal to you, give them a whirl, and they will lead you on a fantastic adventure.

- Read lots of poetry. In fact, read a lot of anything if you want to produce better writing.

- Write poetry as often as you can.

- Designate a special notebook (or space in your notebook) for poetry writing.

- Try writing in form (sonnets, haiku, etc.).

- Use imagery.

- Embrace metaphors, but stay away from clichés.

- Sign up for a poetry writing workshop.

- Expand your vocabulary.

- Read poems over and over (and aloud). Consider and analyze them.

- Join a poetry forum or poetry writing group online.

- Study musicality in writing (rhythm and meter).

- Use poetry prompts when you’re stuck.

- Be funny. Make a funny poem.

- Notice what makes others’ poetry memorable. Capture it, mix it up, and make it your own.

- Try poetry writing exercises when you’ve got writer’s block.

- Study biographies of famous (or not-so-famous) poets.

- Memorize a poem (or two, or three, or more).

- Revise and rewrite your poems to make them stronger and more compelling.

- Have fun with puns.

- Don’t be afraid to write a bad poem. You can write a better one later.

- Find unusual subject matter — a teapot, a shelf, a wall.

- Use language that people can understand.

- Meditate or listen to inspirational music before writing poetry to clear your mind and gain focus.

- Keep a notebook with you at all times so you can write whenever (and wherever) inspiration strikes.

- Submit your poetry to literary magazines and journals.

- When you submit work, accept rejection and try again and again. You can do it and you will.

- Get a website or blog and publish your own poetry.

- Connect with other poets to share and discuss the craft that is poetry writing.

- Attend a poetry reading or slam poetry event.

- Subscribe to a poetry podcast and listen to poetry.

- Support poets and poetry by buying books and magazines that feature poetry.

- Write with honesty. Don’t back away from your thoughts or feelings. Express them!

- Don’t be afraid to experiment. Mix art and music with your poetry. Perform it and publish it.

- Eliminate all unnecessary words, phrases, and lines. Make every word count.

- Write a poem every single day.

- Read a poem every single day.

Have You Written a Poem Lately?

I believe that poetry is the most exquisite form of writing. And anyone can write a poem if they want to. In today’s world of fast-moving images, poetry has lost much of its appeal to the masses. But there are those of us who thrive on language and who still appreciate a poem and its power to move us emotionally. It’s our job to keep great poetry writing alive. And it’s our job to keep writing poetry.

What are some of your favorite writing tips from today’s list? How can you apply poetry writing techniques to other forms of writing? Do you have any tips to add? Leave a comment!

72 Comments

Interesting article! 🙂 Thank you for writing this, Melissa!

Thank you for reading it, Maria!

I find this very helpful in my search to write poetry with some help. I am finding lots of things on the internet. This is my favorite so far.

Thanks for your kind words, Sandy. I’m glad you found this article helpful!

Nice article~ I started writing poetry on a regular basis back in November. Gave myself permission to write really bad stuff without hitting the delete key 🙂

I’d like to see recommendations for poetry blogs ands sites if you don’t mind sharing.

Hi Connie. In my experience, creative freedom (permission to write bad stuff) is essential in poetry writing. Most of the poetry sites I visit are online literary magazines, but I actually get most of my poetry from books. There are some excellent podcasts too — IndieFeed: Performance Poetry and Poem of the Day come to mind as two favorites.

Poem: Our Promise Kiribaku

You promised You promised me the world You promised You promised me your last name You promised You promised me heaven You promised You promised me Money You promised me freedom But now I am shackled by the pain of our broken promise

I have not written a poem lately. I don’t know why, but I only feel compelled to write poetry when I’m overflowing with emotion of some kind. Anger, passion, remorse, grief, love … the things that are so hard to contain in prose and need the stretchier boundaries of poetry to give them the room they need. Otherwise, I’m a down-to-earth, prose girl, and since, as a rule, I’m pretty even-keeled as emotions go … I don’t do the poetry thing very often. I think about it, though. Does that count?

Do you read a lot of poetry? I too tend to get the urge to write poetry when I’m overflowing with emotion, so I know what you mean. And it’s easy to drift away from poetry writing, especially when you’re blogging and writing copy! I don’t know if thinking about it counts, but I guess if your thoughts eventually lead to a poem, then it does count! Ha!

I really don’t read that much poetry, I like to think of myself as a creative person, but I’m still a prose girl at heart. Also, I have an aversion to things that rhyme (other than song lyrics) because sappy Hallmark cards pretty much ruined that for me when I was in my teens (grin).

Hallmark hasn’t exactly been a positive PR machine for poetry in general, has it? But what about Dr. Seuss-ish rhymes? Nursery rhymes? Rhymes in song lyrics? Can you tell I love rhyming? I know what you mean about sappy rhymes and greeting-card poems. When I’m writing (or reading) I always look for clever and unexpected rhymes. That sort of levels out the cheesiness factor.

Hi Melissa,

Thanks for posting this list!

My illustrious poetry career was cut short around the age of 13, when I became more obsessed with journaling about boys than writing witty epic poems commemorating family members’ birthdays.

I’ve decided that this will be the year that I finally open up to poetry again! I’ll probably start up with writing in my signature “grade 6” style of poetry which is likely to include rhymes like “bee” and “pee” and classic highbrow toilet humour. Hopefully I can grow from there. I’m currently trawling through your previous posts and comments for poetry tips, terms and reading suggestions – the one on meter and musicality looks especially good.

You asked for topic requests in a previous post, so here are a few post suggestions that I’d be interested in reading about:

1. A list of your favourite poets or pieces? (I’m currently asking all my friends for suggested readings as a starting point!) 2. More poetic devices or techniques that you may know about?

Hi zz. I’ll have to think about compiling a list of my favorite poems and poets. Some of my favorites are ee cummings, Maya Angelou, Margaret Atwood, Emily Dickinson, and so many more…

Like you, I started writing poetry when I was 13 years old. Since then, I’ve been in and out of poetry writing over the years. It’s comforting to know that I can always return to it. Good luck this year with your poetry!

All the tips are most useful for anyone who wants to become a poet. But it is not easy to follow each and every step. Concentration and hard work is essential to reach the goal.

True, although it depends on the goal. I’ve known a lot of writers who write poetry solely for personal expression. Their poems are private, much like a journal. You’re right in that it’s not easy to follow every step, and becoming a (published) poet takes concentration and hard work.

I think I never write poems because I don’t know when a poem is a poem and when it’s not. I never figured out any simple criteria for something to be a poem.

Do you ever read poetry? I think that learning through example is the best way to figure out what is a poem, although I have come across a few poems that I would consider prose or fiction — these are often referred to as “prose poems.” If you wanted to try your hand at poetry writing, you could always go the traditional route and compose sonnets or haiku. Those are definitely poems.

Thanks for sharing your insights on poetry.It is a nice article.Surely to improve poetry,one has to keep writing and editing.

That’s true. Improvement comes from practice, so keep on writing.

I made a New Year’s resolution to write a poem a day…so far I have strayed from my resolution hehe…nice post

Aw, but you still shouldn’t give up. You can also double up to catch up. Good luck!

Thank you Melissa, I will catch up by doubling up. The hardest thing to do is to employ various poetical techniques in a hip-hop form and present them to an audience that may be too dense to grab or understand dedication to the craft. I have learned that there is a market for everything though.

Don’t underestimate your audience! One of the reasons I fell in love with hip hop was because of its poetry (Jay-Z in particular). Of course, then there was the dance element!

Hi Melissa! Thanks for this site.It feels nice being with people who loves to write and your tips are really very useful. I am a lover of poems and I have tried writing poems myself. I’ve tried to write poems everyday as suggested and I realized that it is good practice…although most of them are not really even worth sharing, but it gives me time to critic my own work and at the same time improve on them. Oftentimes I dream that someday my poems will entertain others the way some poems entertain me, but many I find my poems very shallow. And much as I would like to say that poetry is just a way of expressing myself and sometimes venting myself of some negative feelings so I have to keep them to myself, most of the time, I have the urge to share it to somebody. Sometimes, the beauty of the poem for me is when you are able to share what it is you want to express and somebody else understands it the way you wanted it to be understood. It may be vain, but I think it is also a great feeling when someone says he/she liked my poem. Is it normal for a writer?

Hi Mary. Yes, I think what you’re experiencing is completely normal for a writer. Often, what seems obvious or ordinary to you is fascinating to someone else. If we, as writers, write what we know, then it’s not necessarily new or exciting, but for someone who hasn’t walked in our shoes or lived inside our heads, our words are fresh and compelling.

Of course it’s a wonderful feeling when someone likes your poem! The trick is to also experience a wonderful feeling when someone likes it enough to offer suggestions for improvements: “I like this poem a lot, but it would be even better if…” That’s a sign that someone believes in your work enough to want to help you grow.

My suggestion is to read tons and tons of poetry. There is plenty of great work online, but be sure to explore the classics and literary journals too. Good luck to you!

i have written a lot of poems. where can one send these for publishing….

Hi Charlan. Your question is really beyond the scope of what I can answer in a blog comment. There are hundreds, if not thousands, of publications that accept submissions. But before you submit to any of them, you should read them. I recommend searching for literary magazines, poetry magazines, literary journals, and poetry journals. That should be a good start.

.35 read a poem every day.

Well, there are lots of great tips here, but I thought I’d share a source of poetry that allows me to read a sacred poem everyday. It’s great–stuff all the way from Rumi to Levertov. And it draws on all spiritual traditions. Here’s the link! http://www.poetry-chaikhana.com/

Thanks for sharing that link, Rose. I’ll have to check it out. Great poetry is a bit hard to find online, so I appreciate your suggestion.

I love poetry. I recently got the word tattooed on my right arm. 🙂 Now that I’ve read this, I’m inspired to write a sonnet! Thank you!

Thank you, Lauren. Good luck with your sonnet.

Though I write youth fiction now, I can’t get away from poetry and end up scribbling poetic lines down in my journal every now and then. I guess that stems from my teen music writing days, where I had notebooks full of songs, poetry, whatever. Poetry is such a free form of writing, kind of like dancing 🙂

I couldn’t agree more, Alex. My focus these days is more on fiction and creative nonfiction, but the poems still show up at will. When they do, I write them in my journal. It’s definitely like dancing (a magical kind of dancing).

Melissa Donovan, I could disagree with everything you said, but that would make me a fool. And I am no fool no sir re, although I act a bit like one from time to time. Yes Notebooks galore are stored in my little pad.

I don’t read a lot as I am creating a lot and posting and maintaining my Blogs and websites along with all their supporting Bookmakers and Indexers. Forums are great and workshops are better. But the thing I find most supportive is pretending to be your own Publisher your own Boss.

This is what I am doing day in and day out or whenever the spirits move me. I talk about mostly creating as I am not educated enough in the forms of other poetry just free verse and prose. I guess I should try others forms and I may at a latter date.

But right not I am trying to make my poetry work for me, as I am Home bound and disabled to a great extent. Well I enjoyed this write it states much truth for Poets and Poetesses a like, God Bless and may you Keep on Keeping On!

Donnie/ Sinbad the Sailor Man

I believe that reading is essential to good writing. Many writers have reasons for not reading, but I think the reasons to read are far more convincing. In fact, I think spending an hour a day reading and twenty minutes writing will improve your writing faster and more thoroughly than spending an hour and twenty minutes a day writing. Keep at it, Donnie.

hi melissa, i am 14 and i wrote my firt poem a month ago. since then my school had registered my name for a competition. i am not really experienced and i am worried since i have to write a poem on a topic given by thejudges, in an hour. any tips?

My first tip would be this: don’t take the competition too seriously. It’s an honor that you were selected. Most poets aren’t constrained by a one-hour time limit, but this is definitely an opportunity to have a little fun with your creativity and challenge yourself. I say, just go with it. If you can, give yourself about ten minutes to jot down words and images once you’ve been given your subject. Then spend about thirty minutes working that material into a poem. Use the remaining twenty minutes to edit and revise. Good luck to you, Ash!

These are really good advise. I love point 23 especially, to meditate before penning down. I’ve always find poetry writing a way to connect with my own spirituality. I have always been smitten by poems of others with their powerful rhyming and rhythm, which I always have difficulty pulling it off. It always seem to me that they have not one word wasted. What would you suggest to make an improvement on ths aspect?

The best suggestion I can offer you is to edit your poems slowly and thoughtfully. Poems can happen very quickly and many beginning poets are inclined to go over the poem once or twice, sweeping it rather than giving it a deep cleaning. Spend time with the poem. Look for alternative words in a thesaurus. If you’re having trouble with rhyme, use a rhyming dictionary. If the rhythm is off, use a metronome or play music (without lyrics) while you write, or study music on the side to get a sense of rhythm and meter.

Wow!!!! Found it just awesome.. Yeah I have written some poems, but haven’t published anywhere, so, how can I do it to publish on this site.. This made me, to devote myself more and more for my dream Thaanxx for the article

Hi Nibedit. This is not a publishing platform for poetry, but you can do a search for “poetry journals” and “literary magazines” to find a host of sites that accept work for publication. I wish you the best of luck with your writing!

Well-written tips Melissa! Reading a lot definitely helps you to produce better poetry. I always have a small book in my bag, so that I could write whenever I feel to 🙂

Thanks, Summer! I carry a tiny notebook too, plus my phone, which I can use if I’ve forgotten my notebook for some reason.

Hey, Melissa! I’ve read through your article, but I’m still stuck on how I’m supposed to write a poem with deeper meaning. It seems like every other poem I’ve ever written have the same words on it and I’m running out of ideas of how to start. I would’ve considered myself to be fairly good as a learning poet but now i think I’m doubting myself because i used to know more vocabularies and now i can’t seem to think of any witty writings. I would appreciate any suggestions you may offer.

My best suggestion is to read some poetry and read some books on the craft of poetry. I always found those to the best ways to break through a plateau. You can check my Writing Resources page, where I have listed some of my favorite poetry resources.

I’m 13 and I’m trying to put together a poetry book. It’s about being gay and losing friends because of it, people not liking me back, etc. So far the poems I have written are very good (in my opinion), although depressing. I sent one in to a literary agent asking if it was professional material and he said he would gladly help me publish it.

So, what I wanted to say is that I barely ever read poetry and I can still write well. My ideas, rhythm patterns, rhyme schemes, etc. are original, and I like that about them. I’m not going for perfect or a masterpiece. I just want to get my messages and emotions across, so I don’t read the poetry of others. I can see why other poets would, but I just don’t. I just let myself write, and then I edit and revise whatever I come up with. Just stop when it sounds good.

Also, I want to add that you shouldn’t be afraid to write dark or depressing poetry. Just write with the emotions that you feel inside. Almost all of my poems are depressing, but it doesn’t mean that I cut myself or anything. So don’t be afraid to do that. (Writing depressing poetry, not cutting yourself. Lol)

Good luck to all of you aspiring poets out there!

Thanks, Thomas

Thomas, I think it’s wonderful that you’re writing poetry at age thirteen (coincidentally, that’s the age I started writing it, too) and that you’re using poetry to express yourself and address important social issues. I applaud you!

However, I cannot get on board with the notion that one can write great poetry without reading it. You say you write good poems, but how could you possibly know whether your poems are good if you don’t read any other poetry? What, exactly, are you comparing your poems to? You may very well be a born talent, but I can assure you that if you study your craft, your poems will be a thousand times better.

You say “I just want to get my messages and emotions across, so I don’t read the poetry of others.” It sounds to me like you want the world to listen to you but you don’t want to listen to anyone else, which is too bad. I hope that in time, you’ll change your mind and decide to embrace poetry in full, which means reading it as well as writing it.

I do enjoy reading a poem everyday. I subscribed to Academy of American Poets Poem A Day. That way I’m sure to read a different poem each day delivered to my email. The last time I wrote a poem was a week ago. I need to get back into a better routine with writing poetry. I enjoy it very much and I do try to find different journals and contests to submit my poetry to at least a few times a year. Thanks for the motivation with this article.

I’ve always viewed poetry as the most artistic (and sometimes magical!) form of writing. I just wish more people would embrace it.

hi. i’ve been so empty lately. the thought of making poems is that it interests me, at my good times and bad times. i dont know if it is talent or something. they dont even know, my friends and my family. im a little shy and ashame about it. they would say poetry sucks, its not for you, they would never understand the feeling. this is what i really love to do . i want to play with words. they found me. help me understand it. thanks.bye

If you want to make poems, then make poems. Other people don’t get to decide how you spend your free time. Why on earth would you be ashamed about wanting to write poetry? There are always people who want to shame and bully people because they are different. Don’t let them control you. Can you imagine shaming someone because they like soccer or knitting?

Ms Melissa, Also “steal” techniques and then perfect them to your purpose.

Thank you so much for this article Melissa! I wanted to write a book on my life for so many years but decided it would hurt too many people, even though they never thought about their actions. I woke up one morning and wrote poems(literally) based on the way i felt which I felt was less hurtful but more direct and expressive! My poems are free form and I’ve been reading up on writing good poetry. Although I find it difficult to fit to the guidelines. This article really helps! Cheers!

Hi Gayle! I’m so glad you liked this article. I once had an idea for a book based on real life, but like you, it wasn’t worth it to risk upsetting people, and I had plenty of other things that I wanted to write. Actually, it was a good way to eliminate an idea at a time when I had too many of them! And I agree that poetry is the most expressive and cathartic form of writing. Thank you for your comment.

Thank you so much for this fantastic article Melissa. I have just published my first book and working on my next one. I’m always on the outlook for crafted information to help me as a writer. I have developed my own style when writing poetry but it’s always nice to dapple using different ideas and constraints. Thanks…

You’re welcome, David. Congratulations on finishing your first book. May there be many more to follow!

This is encouraging. I’ve written a couple of poems but didn’t think they were good enough. Now I know there are really no limits. Thanks!

I’m glad you found this encouraging, Grace. As long as you stick with it, there are no limits. Keep writing.

Thanks beloved friend & Poetess I appreciate all your tips Everyone is On point, Phenomenal brilliant Food for a, poetry writer & speaker To use.

Lovely! Thanks, Jeffrey.

I’ve been writing poetry for years and have a collection of books on Amazon. When it comes to critique from your audience, it may surprise you! You might find teachers, other poets, writers and artists love your work. However, you will get feedback from people who hate your words. They will be harsh and leave you with a terrible review. This doesn’t mean you should stop and feel terrible, it just means you didn’t resonate with that person. Every type of creative work is open to good and bad feedback. It’s all part of the process. Just keep doing what you love.

This is so true. All art is subjective. I’ve had some interesting debates with people who don’t care for the poetry of ee cummings. Personally, I love his work. Unfortunately, reviewers often lack objectivity. For example, a trained and experienced reviewer can probably acknowledge the merit of a work while expressing their dislike (“it’s good work but not to my taste”). Some say you haven’t really “made it” until you get your first negative review. Writers can use feedback to grow and improve, but we should not let negative reviews impede our progress or determination. Thanks for your comment!

I lost my muse trying to find it again. So I wrote this

consciously asleep

Yellow is the sun Blue is the sky Hot is the desert Blank is the heart

Filled is the store Hungry do we wake

Many are they None is there

Alive we are Dead are we walking

Happy is the face Sad is the heart

Many are friends Lonely is he

Beauty is the body Ugly is the being

Island do we dwell Thirst are we

Kings are we born Shackles around neck

Love do they preach Hate do we see

Blessed are we born Cursed are we

Perfect is the earth made Chaos do we see

Mercy sowth the creator Vengeance ignited the creation

Noises do we hear Yet deaf are we.

Thank you for sharing your poem with us. Lovely.

This list is awesome. The one item on the list that renosontes with me would be supporting your favorite poets, your local poets, and read their marietial. I recently had a poem accepted by Spillwords called “Running with Scissors.” I’d like to attend a poetry slam in the future.

Thanks, Donetta! I too would love to attend a poetry slam. They look so fun!

You have some wonderful tips here. 🤍🌺 I’ve learned so much!

Thanks, Kymber! I love how you use the Sims to illustrate your stories! That’s awesome.

Thanks for this wonderful post. In December last year I committed myself to write one poem a day for a year. So far, I’m on track, but am running out of inspiration. Some of my poems are traditional rhyming poetry, one or two are free verse. I’ve written some Haiku, a few limericks, one or two narrative poems and some on things I feel deeply about, like what we are doing to our lovely planet. I hope to publish in two volumes–January to June and July to December. People will then be able to read one poem each day for a year.

What a fun challenge. I always mean to write a poem a day in April for National Poetry Month, but I keep forgetting! That seems to be a busy time of year for me.

I write a lot of poetry and have published a couple of collections. But with no rules, I wonder if there are more things I should know. I do/have done most of your list, but there are some good additions here. Thanks

You’re welcome!

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Subscribe and get The Writer’s Creed graphic e-booklet, plus a weekly digest with the latest articles on writing, as well as special offers and exclusive content.

Recent Posts

- Should You Write Fast or Write Well?

- Writing Tips: Kill Your Darlings

- Writing Resources: A Poetry Handbook

- 12 Nature-Inspired Creative Writing Prompts

- Poetry Writing Exercises to Engage the Senses

Write on, shine on!

Pin It on Pinterest

9 Essential Poetry Writing Techniques For Beginners: A Complete Guide

Poetry writing techniques.

Diving into poetry can feel like wandering through a beautiful, mysterious forest—exciting but a bit intimidating.

Our guide is your trusty map, showing you how to wield these techniques and craft verses that resonate and captivate. Get ready—your poetic journey awaits!

Key Takeaways

Table of contents, the importance of poetic techniques.

They turn simple phrases into rich experiences and help readers feel emotions and see images in their minds.

Poets use tools like alliteration, assonance, and rhyme to make their work memorable.

These techniques give poems a rhythm that can make you feel like you’re dancing through the verses.

Metaphors take this further by saying something is something else entirely, deepening the meaning.

By mastering poetic devices , writers create worlds that readers can get lost in. They learn how to say more with less and connect deeply with those who read their creations.

Essential Poetic Techniques for Beginners

To craft verses that resonate and captivate, mastering a few essential poetic techniques is critical – these are the tools that will shape your raw thoughts into structured elegance and expressive power.

Rhyming creates a musical rhythm in poetry, making it more memorable and enjoyable to read or listen to.

Think about popular nursery rhymes you heard as a child; they stick with us because of their simple yet effective rhyming patterns.

To master musicality in your poems, mix up your rhyme scheme.

The key is to create flow without sounding forced. Rhyming isn’t just for classic forms like sonnets or ballads— modern free verse can play with partial rhymes to add subtle harmony.

Moving from rhyming to repetition, we dive into another powerful tool in poetry. Repetition hammers home a point or theme.

A repeated word or phrase can echo throughout a poem, tying ideas together and making the message stick.

For beginners, mastering repetition is about knowing why and where it’s effective. Use it to emphasize an emotion , create rhythm , or build tension.

Think of William Shakespeare and his knack for repeating lines that resonate long after you’ve read them – that’s the poetic power of careful repetition at work!

Onomatopoeia

Repetition captures attention, while onomatopoeia brings sounds to life . Imagine reading a poem and hearing the actual noise of what’s happening.

These words create an echo of real-life noises in your mind. Onomatopoeia doesn’t just tell you about the sound; it makes you experience it.

When poets pick these particular words , they paint a vivid picture with audio effects .

Alliteration

Alliteration grabs your attention with the repetition of initial consonant sounds . Think of tongue twisters, like “She sells seashells by the seashore.”

In poetry, it’s a powerful sound device that poets use to add a musical rhythm and make their words memorable.

Using alliteration , poets can create an atmosphere or emphasize essential themes in their poetry.