Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Inclusive Education: Literature Review

The education of disabled children never received such amount of consideration and special efforts by government and non-government agencies in past as in present days. The attitude of the community in general and the attitude of parents in particular towards the education of the disabled have undergone change with the development of society and civilization.

Related Papers

vatika sibal

Executive Summary In India, inclusive education for children with disability has only recently been accepted in policy and in principle. In light of supportive policy and legislation, the present paper argues for individual initiative on part of an institution and colleges to implement programmes of inclusive education for children with disabilities in their classrooms. The paper provides guidelines in a generalized mode that institutions can follow to initiate such programmes. In this context, this paper argues for individual initiative on part of institutions to extend facilities for children with disabilities within their regular school settings. The paper further provides guidelines that institutions can adopt to set up inclusive education practices. The guidelines were derived from an empirical study which entailed examining prevalent practices and introducing inclusion in a regular institution setting. It is suggested that institutions can implement inclusive education programmes if they are adequately prepared, are able to garner support of all stakeholders involved in the process and have basic resources to run the programmes. The guidelines also suggest ways in which curriculum adaptations, teaching methodology and evaluation procedures can be adapted to suit needs of students with special needs. Issues of role allocation and seeking support of parents and peers are also dealt with. The recommendations that intuitions can adopt to implement inclusive education programmes for students with special needs within their regular set ups. The recommendations have been presented in a generalized mode to permit institute to interpret, modify and adapt the guidelines based on their individual needs and characteristics. It is pertinent those institutes that initiate such programmes assess their strengths and weaknesses at the outset and ensure adequate cooperation from the school management as well as the administrative and teaching staff. It is important to state here that an inclusive education programme does not require resource overload or elaborate preparations. With policy support, opportunities for training of teachers and cooperation from parents and the peer group, inclusive practices can be effectively adopted by any school. Clarity of vision, commitment to the goal of inclusion, and a perceptible understanding of the nuances involved in such an initiative are central to the success of the programme. Emotional commitment to inclusion emerges when the intellectual understanding of the concept goes through a democratic visioning process involving all the stakeholders expressing their opinions and feelings.

Inclusive Education: children with disabilities - - Background paper prepared for the 2020 Global Education Monitoring Report Inclusion and education 2020

Paula Frederica Hunt

This paper presents the case for inclusive education for children with disabilities as the entry point for policy development and implementation of inclusive education in the broad sense: inclusive, quality education for ALL children. The paper starts by providing a short historical perspective of the education of children with disabilities and continues with a description of the essential elements of an inclusive legislative framework, with a particular focus on General Comment no4 of Article 24 (CRPD). The benefits of inclusive education, as well as financing mechanisms, and required accountability measures for implementation, are also discussed. Then, the paper discusses the foundational basis of curriculum for inclusion, as well as issues related to a transformative teacher education practice. The final chapters describe what an inclusive school might look like, as well as the role of students, families and communities in creating an inclusive education system. It should be noted that this paper is substantiated with selective literature, with attention payed to an equitable geographic coverage.

ankur madan

Research Anthology on Inclusive Practices for Educators and Administrators in Special Education

Shekh Farid

BRAC, a leading international development organization, has been working to ensure the rights of persons with disabilities to education through its inclusive education program. This article discusses the BRAC approach in Bangladesh and aims to identify its strategies that are effective in facilitating inclusion. It employed a qualitative research approach where data were collected from students with disabilities, their parents, and BRAC's teachers and staffs using qualitative data collection techniques. The results show that the disability-inclusive policy and all other activities are strongly monitored by a separate unit under BRAC Education Program (BEP). It mainly focuses on sensitizing its teachers and staff to the issue through training, discussing the issue in all meetings and ensuring effective use of a working manual developed by the unit. Group-based learning and involving them in income generating activities were also effective. The findings of the study would be usefu...

Shonazar Botirov

This article describes the introduction of inclusive education, what it is, about children with disabilities, as well as the positive and negative aspects of inclusive education.

Ikhfi Imaniah

This paper identifies and discusses major issues and trends in special education in Indonesia, including implications of trends for the future developments. Trends are discussed for the following areas: (1) inclusion and integration, issues will remain unresolved in the near future; (2) early childhood and postsecondary education with disability students, special education will be viewed as lifespan schooling; (3) transitions and life skills, these will receive greater emphasis; and (4) consultation and collaboration, more emphasis but problems remain. Moreover, the participant of the study in this paper was an autism student of twelve years old who lived at Maguwoharjo, Yogyakarta. This study was qualitative with case study as an approach of the research. The researchers conclude the autism that has good academic, communication and emotional skill are able to go to integrated school accompanied by guidance teacher. But in practice, inclusive education in Indonesia is inseparable from stakeholders ranging from government and institutions such as schools, educators, school environment, community and parents to support the goal of inclusive education itself. Adequate infrastructure also needs to be given to the school that organizes inclusive education for an efficient and effective students understanding learning-oriented of inclusive education. In short, every child has the same opportunity in education, yet for special education which is aimed at student with special educational needs.

Rajendra KR

Inclusive Education on Children with Learning Disabilities

Arien Arien

ABSTRACT Name : Zahrien Assyifa Nur Palisma NISN : 0002223086 Title : Analysis of Inclusive Education on Children with Learning Disabilities (Case study on 4th Grade of Mutiara Bunda Elementary School, Cilegon Banten Inclusive Education is an approach that aims to change the education system by translating barriers that can accommodate every student to participate fully in education. That is, every child is entitled to a decent education, not to mention children with learning disabilities. Children with learning disabilities are interpreted as children who find it difficult to receive formal and non-formal learning because of certain psychological "disabilities". This study aims to determine how much the effectiveness of inclusive education for children with learning disabilities in Mutiara Bunda Elementary School, Cilegon. The method used by the author is the field research that is carried out on October 6th, 2017 at Bunda Mutiara Elementary School, Street. Boulevard Raya Block A2 Number.6 Taman Cilegon Indah, Sukmajaya, Cilegon Banten.The results obtained from this study are: a. Inclusive Education is the right solution for children with learning disabilities even for all children with disabilities. b. The curriculum used in inclusive schools is similar to the curriculum in public schools. There is little modification in children with learning disabilities as well as some omissions and curriculum substitutions. Keywords: Inclusive Education, Children with Learning Disabilities

Swati Chakraborty

International Journal of …

Missy Morton

RELATED PAPERS

American Yearbook of International Law – AYIL, Volume 2

Virginia Balafouta

História da Educação

Danilo Romeu Streck

Journal of Surgical Research

Indonesian Journal of Tropical and Infectious Disease

prihartini widiyanti

Ecological Applications

Joseph O'Brien

Marilda Martins Fayad

Engineering in Life Sciences

oluwaseun Adelaja

Jan Pralits

Howard Liddle

Journal of Oral Implantology

Sebastiano Andreana

Koko Warner

Enzyme and Microbial Technology

Dr Rooma Devi

Mats Wiklund

Procedia CIRP

Erik Sundin

Biochemical pharmacology

Education + Training

Bayan Ustwani

Türk Kütüphaneciliği

Mehmet Toplu

Zhenming Wang

hemangi bawane

Mathematics in industry

Rick Janssen

Radiotherapy and Oncology

Cristiana Fodor

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Review of Literature: Inclusive Education

This brief review of relevant literature on inclusive education forms a component of the larger Inclusive School Communities Project: Final Evaluation Report delivered by the Research in Inclusive and Specialised Education (RISE) team to JFA Purple Orange in October, 2020.

Suggested citation for full evaluation report:

Jarvis, J. M., McMillan, J. M., Bissaker, K., Carson, K. L., Davidson, J., & Walker, P. M. (2020). Inclusive School Communities Project: Final Evaluation Report. Research in Inclusive and Specialised Education (RISE), Flinders University.

https://sites.flinders.edu.au/rise

Introduction

Inclusive education has featured prominently in worldwide educational discourse and reform efforts over the past 30 years (Berlach & Chambers, 2011; Forlin, 2006). Inclusive schools are critical to providing a strong foundation for young people with disabilities to access, participate in and contribute to their communities and lead fulfilling lives (Hehir et al., 2016). Schools also represent a key condition for the development of thriving, inclusive communities for all citizens. Yet, as reflected in submissions to the current Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability, and consistent with recent South Australian reports (Parliament of South Australia, 2017; Walker, 2017), many students living with disability (and their families) continue to report negative experiences of education. While progress has been made, traditional educational structures and practices often run counter to inclusive goals (Slee, 2013), and inconsistencies occur between theory and policy and the implementation of inclusive principles and practices in schools (Carrington & Elkins, 2002; Graham & Spandagou, 2011). In addition, both preservice and practicing teachers consistently report feeling underprepared to teach students with disabilities and special educational needs (Jarvis, 2019; OECD, 2019).

Despite legislation and policy imperatives related to inclusive education, there remains a lack of consensus in the field about the definition of inclusion and associated models of inclusive practice (Ainscow & Sandill, 2010; Kinsella, 2020). Multiple conceptualisations of inclusion and theoretical approaches to fostering inclusion in schools may contribute to confusion and uncertainty for educators and policymakers. With schools facing growing accountability and teachers expected to educate an increasingly diverse student population (Anderson & Boyle, 2015), it is vital that the concept of inclusive education is demystified for practitioners. Against this backdrop, initiatives such as the Inclusive School Communities (ISC) project that aim to deepen understandings of inclusion and increase the capacity of school communities to provide an inclusive education, are particularly important.

Inclusive Education

Inclusive education is based on a philosophy that stems from principles of social justice, and is primarily concerned with mitigating educational inequalities, exclusion, and discrimination (Anderson & Boyle, 2015; Booth, 2012; Waitoller & Artiles, 2013). Although inclusion was originally concerned with ‘disability’ and ‘special educational needs’ (Ainscow et al., 2006; Van Mieghem et al., 2020), the term has evolved to embody valuing diversity among all students, regardless of their circumstances (e.g., Carter & Abawi, 2018; Thomas, 2013). Among interpretations of inclusion, common themes include fairness, equality, respect, diversity, participation, community, leadership, commitment, shared vision, and collaboration (Booth, 2012; McMaster, 2015). The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), to which Australia is a signatory, defines inclusive education as:

. . . a process of systemic reform embodying changes and modifications in content, teaching methods, approaches, structures and strategies in education to overcome barriers with a vision serving to provide all students of the relevant age range with an equitable and participatory learning experience and environment that best corresponds to their requirements and preferences. (United Nations, 2016, para 11)

Consistent with this definition, inclusive education now generally refers to the process of addressing the learning needs of all students, through ensuring participation, achievement growth, and a sense of belonging, enabling all students to reach their full potential (Anderson & Boyle, 2015; Booth, 2012; Stegemann & Jaciw, 2018). Inclusion is concerned with identifying and removing potential barriers to presence (attendance, access), meaningful participation, growth from an individual starting point, and feelings of connectedness and belonging for all students and community members, with a focus on those at particular risk of marginalisation or exclusion (Ainscow et al., 2006; Forlin et al., 2013).

Critically, the view of inclusion described above moves beyond considerations of the physical placement of a student in a particular setting or grouping configuration. That is, while physical access to a mainstream school environment is essential to maintain the rights of students living with disabilities to access education “on the same basis” as their peers (consistent with legislation and human rights principles), it is not sufficient to ensure inclusion. Rather, inclusion can be considered a multi-faceted approach involving processes, practices, policies and cultures at all levels of a school and system (Booth & Ainscow, 2011). Inclusive education is responsive to each child and promotes flexibility, rather than expecting the child to change in order to ‘fit’ rigid schooling structures. The latter approach reflects integration, and inclusion is also inconsistent with segregation, in which children with disabilities are routinely educated separately from others.

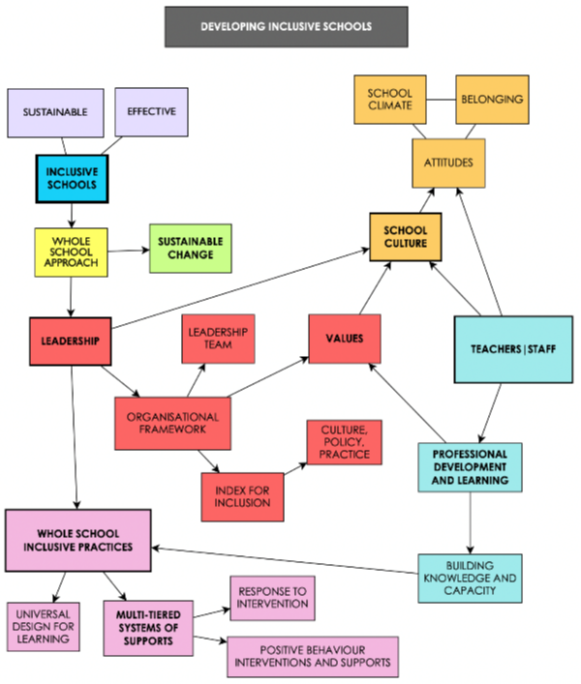

Considerable research has focused on the implementation of inclusive school processes, practices and cultures that are sustainable over time. Although a number of frameworks to achieve sustainable inclusive practice have been proposed, key elements are consistent across approaches and well supported by research (Booth & Ainscow 2011; Azorín & Ainscow, 2020). These interconnected elements are summarised in Figure 1 and considered fundamental to the process of achieving whole-school (and systemic) cultural change towards more inclusive ways of working. Of particular relevance to the Inclusive School Communities project are the concepts of a whole school approach, leadership, school values and culture, building staff capacity, and multi-tiered models of inclusive practice.

Inclusion as a Whole School Approach

Adopting a whole of school approach to inclusive education is fundamental to ensure efficacy and sustainability (Read et al., 2015). The process of developing inclusive schools is complex and multi-faceted, requiring time, commitment, ongoing reflection, and sustained effort. For inclusion to truly take root in schools, changes must be made from the inside out; a strong foundation must be built from inclusive school values, committed leadership, and shared vision amongst staff to support whole school structural reforms to policy, pedagogy, and practice (Ekins & Grimes, 2009). Whilst challenging, “it is necessary to unsettle default modes of operation” in schools (Johnston & Hayes, 2007, p.376), as inclusive education requires new, more efficient and effective ways of supporting student participation and achievement. This is made possible by implementing flexible, planned whole school support structures, such as multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS), where teachers work collaboratively with specialist staff to identify, monitor, and support students requiring varying levels and types of intervention at different times, and for different purposes (Sailor, 2017; Witzel & Clarke, 2015). This contrasts to the more traditional, ‘categorical’ and segregated approach of general educators referring identified students with additional needs to special educators, to devise and administer further education in isolation from the regular classroom (Sailor, 2017).

Figure 1. Interconnected elements in sustainable inclusive education, derived from research.

Even at the classroom level, inclusive planning and teaching practices must be supported by school policies, practices, and culture in order to be sustainable (Sailor, 2017). Barriers to inclusive classroom practice can include lack of effective professional learning and support for teachers; teachers’ lack of willingness to include students with particular needs; attitudes that are inconsistent with inclusive practices; teacher education that fails to address concerns about inclusion; and, a lack of accountability for the implementation of inclusive teaching practices (Forlin & Chambers, 2011; Forlin et al., 2008; van Kraayenoord et al., 2014). Addressing each of these relies on targeted, coordinated support. The complexity of embedding inclusive practices such as differentiated instruction or Universal Design for Learning (UDL) into classroom work is often underestimated, and these practices have the greatest chance of becoming embedded when they are reinforced by a shared vision and collaborative effort (McMaster, 2013; Sailor, 2015; Tomlinson & Murphy, 2017).

Sustainable, whole school change cannot be achieved via focus on a single element of inclusion in isolation, as components do not function in isolation. Rather, the core elements of inclusion including leadership, school culture, building staff capacity, and inclusive practices are parts of an interdependent system. Hence, key elements of inclusion must be considered collectively and accounted for in advanced planning to ensure they function harmoniously and are integrated into the developing inclusive fabric of the school (Alborno & Gaad, 2014).

Leadership for Inclusion

The importance of leadership for determining the success of school reforms or changes to practice is well established in the literature (McMaster & Elliot, 2014; Poon-McBrayer & Wong, 2013). Becoming a more inclusive school often requires significant shifts in school values, culture, practices, and organisational systems; thus, leadership is critical to ensuring sustainable inclusive change in schools (Ainscow & Sandill, 2010; McMaster, 2015; Poon-McBrayer & Wong, 2013). School leaders are highly influential figures whose values, beliefs, and actions directly affect the culture of the school, expectations of staff, and school operations (Slater, 2012; Wong & Cheung, 2009). It is critical that school leaders are committed to embodying inclusive principles, establishing and modelling a standard of behaviour that promotes the development of inclusion within the school community.

Organisational change on the scale often required for inclusion requires leadership across multiple levels (Jarvis et al., 2016; Tomlinson et al., 2008). It is likely to be most effective when facilitated through models of distributed leadership across roles and levels within a school, and when the case for change is underpinned by a broader, shared vision specifically related to student outcomes (Harris, 2013). Research has established the relationship between distributed leadership practices and the implementation of effective, inclusive school practices (Miškolci et al., 2016; Mullick et al., 2013; Robinson et al., 2008; Sharp et al., 2020). Leaders should consider utilising inclusive styles of management, replacing hierarchical structures with leadership teams (Ainscow & Sandill, 2010; McMaster, 2015). Effective school leadership enables shared responsibility, vision, and consistency within the school community, which is vital for the successful implementation of inclusion (Poon- McBrayer & Wong, 2013).

Fostering Inclusive School Cultures

Developing an inclusive school culture is a fundamental component of developing sustainable inclusion in schools (Dyson et al., 2004; McMaster, 2013). The culture of a school is made up of the shared values, attitudes, and beliefs of the school community (Booth, 2012). Transitioning to a truly inclusive culture requires close attention to attitudes and general support of the inclusive values being adopted, particularly by staff, but also by students and the broader school community (Dyson et al., 2004; Forlin & Chambers, 2011).

A whole school approach to inclusion prompts a school to reflect on and embrace values based on inclusive principles, such as equality, diversity, and respect. This process cannot be imposed, but should be a collaborative exercise with school leaders and staff, to ensure any pedagogical philosophies or practices based on outdated ideas or past assumptions are not operating by default (Johnston & Hayes, 2007; Schein, 2004). Evaluating and redefining existing school values also requires professional learning, to facilitate a collective reconceptualisation of inclusion specific to the unique context of the school; the meaning, aims, and expectations of inclusion must be clarified for the school community, to encourage a shared understanding, vision, and responsibility for supporting the inclusive changes unfolding within the school (Horrocks et al., 2008; Symes & Humphrey, 2011). Finally, it is vital that school policies and practices are regularly revised, to ensure that they reinforce the inclusive values and culture of the school; otherwise, they can act as a potential barrier to the development of sustainable whole school inclusion (Dybvik, 2004; McMaster, 2013).

Building Teachers’ Capacity for Inclusive Practice

Building the knowledge and capacity of teachers and other school staff is crucial to developing sustainable inclusion in schools. The evolution of an inclusive school culture depends on aligning the attitudes and behaviour of staff (McMaster, 2015). Teachers must be knowledgeable about how inclusive education has progressed over time, particularly how the meaning of inclusion has changed and what it means in their school context. Understanding the concepts and values behind inclusion can help teachers appreciate its significance, prompting reflection of their own practice and how they see their students (Anderson & Boyle, 2015; Skidmore, 2004). This can allow any unhelpful assumptions or beliefs that may have been unconsciously informing their teaching practice, particularly in relation to students living with disability, to be challenged and revised (Ashby, 2012; Ashton & Arlington, 2019).

While attention to attitudes, values, and broad understandings is fundamental, the goals of inclusion will only be achieved when principles are consistently enacted in daily classroom practice. At the classroom level, inclusion relies on teachers’ willingness and capacity to apply evidence-informed inclusive practices, such as Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and Differentiated Instruction (Van Mieghem et al., 2020). UDL is a planning framework for learning activities designed to maximise curriculum accessibility for all students by offering multiple opportunities for engagement, representation, and action and expression (CAST, 2018; Sailor, 2015). Differentiated Instruction (DI) is a holistic framework of interdependent principles and practices that enables teachers to design learning experiences to address variation in students’ readiness, interests and learning preferences (Tomlinson, 2014). UDL is primarily focused on inclusive task design, although the model has been expanded in recent years to include greater attention to pedagogy. Differentiation encompasses elements of planning (clear, concept-based learning objectives; formative assessment to inform proactive decision-making for diverse students), teaching (strategies to differentiate by readiness, interest and learning preference; ensuring respectful tasks and ‘teaching up’), and learning environment (flexible grouping, classroom management, establishing an inclusive culture) (Jarvis, 2015; Tomlinson, 2014).

The application of UDL and DI principles and practices by skilled teachers enables diverse students to access curriculum content in multiple ways (Kozik et al., 2009; McMaster, 2013), at appropriate levels of challenge and support to ensure learning growth, and in ways that support motivation, engagement, and feelings of connection and belonging (Beecher & Sweeney, 2008; Callahan et al., 2015; van Kraayenoord, 2007; Stegemann & Jaciw, 2018). These complementary frameworks apply to all students and define general, flexible classroom practices that also reduce the need for individualised adjustments for students with identified disabilities and specialised learning needs. However, in inclusive classrooms, teachers must also develop the knowledge and skills to make and implement reasonable adjustments and accommodations that enable students with identified disabilities and more complex needs to engage with curriculum and assessment ‘on the same basis’ as their peers, as defined within the Disability Standards for Education (Davies et al., 2016).

While inclusive teaching and classroom practices are non-negotiable, the challenge for some teachers to master the necessary skills and achieve the significant shift away from traditional teaching practices is often underestimated (Dixon et al., 2014; Tomlinson & Murphy, 2015). It is well-documented that teachers often find it difficult to apprehend both the conceptual and practical tools of DI and to embed differentiated practices into their daily work (Dack, 2019), particularly when they are not adequately resourced or supported to do so (Black-Hawkins & Florian, 2012; Brigandi et al., 2019; Fuchs et al., 2010; Mills et al, 2014). Perhaps related to teachers’ perceived lack of competence and confidence, the past 5-10 years have seen an enormous increase in the employment of teacher aides to work alongside students with disabilities in mainstream classrooms, despite limited evidence for its effectiveness and often in the context of inadequate planning and oversight (e.g., Sharma & Salend, 2016).

Engagement in targeted professional learning (PL) is fundamental to supporting the shift towards inclusive teaching. Yet, traditional approaches to PL have been criticised for a lack of systematic evaluation and inadequate adherence to principles of effectiveness (Avalos, 2011; Merchie et al., 2018). Research on effective professional learning for teachers has established common principles and practices that are associated with changes in practice, and these also align with teachers’ stated preferences (Walker et al., 2018). These include:

- professional learning is embedded in teachers’ own work contexts, and requires teachers to engage with content that is highly relevant to their daily practice, and closely linked to student learning (Desimone, 2009; Easton, 2008; Spencer, 2016; Van den Bergh et al., 2014);

- professional learning enables teachers to learn together with colleagues, such as in communities of practice (Gore et al., 2017; Voelkel & Chrispeels, 2017);

- professional learning activities are supported by robust school leadership and linked to broader school values and goals (Carpenter, 2015; Frankling et al., 2017; Sharp et al., 2020; Tomlinson et al., 2008; Whitworth & Chiu, 2015);

- professional learning is provided over extended periods, is led by facilitators with expert knowledge, and includes timely follow up activities such as mentoring and coaching to embed changes in practice (Desimone & Pak, 2017; Grierson & Woloshyn, 2013; Tomlinson & Murphy, 2015).

Multi-tiered Approaches to Whole School Inclusive Practice

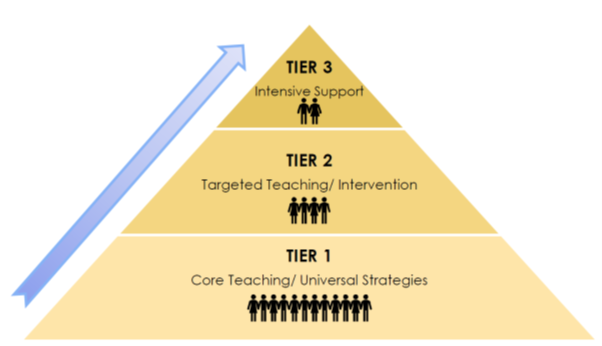

Multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS) is an overarching term for a whole school inclusive framework that can be used to structure the flexible, timely distribution of resources to support students depending on their level of need (Sailor, 2017). As reflected in the generic depiction of MTSS in Figure 2, models generally utilise three tiers of intervention and teaching, where the intensity of the support is increased with each level or tier (McLeskey et al, 2014; Witzel & Clarke, 2015). Tier 1 includes core differentiated instruction and universal, evidence-based strategies for support that all students in the class receive. Tier 2 provides additional, targeted support to certain students for a specified purpose and period of time, usually in a small group format, while Tier 3 represents the most intensive and individualised support (Webster, 2016). The MTSS approach requires assessing all students regularly to assist in the early identification of needs requiring additional support, to enable prompt delivery of targeted interventions (McLeskey et al., 2014). MTSS is concerned with supporting the holistic development of students, by targeting their academic progress, behaviour, and socio-emotional well- being (McMillan & Jarvis, 2017).

When implemented with fidelity, MTSS is an effective whole school inclusive framework as teachers, therapists, and other support staff work collaboratively to assess, monitor, and plan interventions to support students (Sailor, 2017). Student progress is frequently monitored and data are evaluated by the support team to determine whether alternative interventions are required. MTSS additionally encourages the use of evidence-based practices to be implemented across the tiers of support. Some common examples of MTSS include Response to Intervention (RTI) and Positive Behaviour Interventions and Supports (PBIS) (Webster, 2016). RTI is focused on supporting students academically, while PBIS is concerned with emphasising behavioural expectations in a positive manner, naturally supporting the social and emotional development of students. MTSS models have also been applied in whole-school mental health promotion, prevention and intervention (McMillan & Jarvis, 2017) and inclusive approaches to academic talent development for more advanced students (Jarvis, 2017).

MTSS approaches to contemporary inclusive practice stand in contrast to traditional, categorical models whereby students were either ‘in’ or ‘out’ of special education services. The focus is on determining and responding to what students need when they need it, as opposed to focusing on a specific diagnosis or inflexible program options. In the MTSS framework, the tiers do not represent students or their placement, but the flexible suite of supports and interventions that may be provided. The implementation of MTSS approaches fundamentally reconceptualises the role of the classroom teacher, who must work collaboratively with specialist staff and other professionals to define and address individual student needs in ongoing ways, rather than relying on a specialist teacher or even a teacher aide to take responsibility for the education of students with identified special needs. While MTSS requires substantial changes to school operations (and must therefore be supported by leadership and culture in deliberate, coordinated ways), the general framework provides an organisation and structure to support the development of sustainable, contemporary inclusive schools (McLeskey et al., 2014).

Figure 2. Multi-tiered System of Supports (MTSS) framework.

Conclusion

Ultimately, developing sustainable and effective inclusion in schools is a challenging but worthwhile undertaking, requiring shared vision, commitment, ongoing reflection, and patience. Changes in practice, particularly in teachers’ daily planning and pedagogy, take time and will be supported by ongoing, well designed and embedded professional learning in the context of strong leadership and an inclusive school culture. By utilising a whole school approach, key areas including leadership, school values and culture, building staff capacity, and coordinated frameworks for inclusive practice, can be considered collectively and planned for in advance.

References

Ainscow, M., & Sandill, A. (2010). Developing inclusive education systems: The role of organizational cultures and leadership. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 14 (4), 401–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110802504903

Ainscow, M., Booth, T., & Dyson, A. (2006). Improving Schools, Developing Inclusion. Routledge.

Alborno, N., & Gaad, E. (2014). Index for Inclusion: A framework for school review in the United Arab Emirates. British Journal of Special Education, 41 (3), 231–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8578.12073

Anderson, J., & Boyle, C. (2015). Inclusive education in Australia: Rhetoric, reality and the road ahead. Support for Learning, 30 (1), 4–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9604.12074

Ashby, C. (2012). Disability studies and inclusive teacher preparation: A socially just path for teacher education. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 37 (2), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F154079691203700204

Ashton, J. R., & Arlington, H. (2019). My fears were irrational: Transforming conceptions of disability in teacher education through service learning. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 15 (1), 50–81.

Askell-Williams, H., & Koh, G. (2020). Enhancing the sustainability of school improvement initiatives. School Effectiveness and School Improvement. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2020.1767657

Avalos, B. (2011). Teacher professional development in teaching and teacher education over ten years. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27, 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.007

Beecher, M., & Sweeney, S. M. (2008). Closing the achievement gap with curriculum enrichment and differentiation: One school’s story. Journal of Advanced Academics, 19 (3), 502–530. https://doi.org/10.4219/jaa-2008-815

Berlach, R. G., & Chambers, D. J. (2011). Interpreting inclusivity: An endeavour of great proportions. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 15, 529–539. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110903159300

Black-Hawkins, K. & Florian, L. (2012). Classroom teachers’ craft knowledge of their inclusive practice. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 8 (5), 567–584. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2012.709732

Booth, T. (2012). Creating welcoming cultures: The index for inclusion. Race Equality Teaching, 30 (2), 19–21. http://doi.org/10.18546/RET.30.2.07

Booth, T., & Ainscow, M. (2011). Index for Inclusion: developing learning and participation in schools (3rd ed.). Centre for Studies on Inclusive Education. http://www.csie.org.uk/resources/inclusion-index-explained.shtml

Brigandi, C., Gibson, C. M., & Miller, M. (2019). Professional development and differentiated instruction in an elementary school pull-out program: A gifted education case study. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 42 (4), 362–395. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353219874418

Callahan, C. M., Moon, T. R., Oh, S., Azano, A. P., & Hailey, E. P. (2015). What works in gifted education: Documenting the effects of an integrated curricular/instructional model for gifted students. American Education Research Journal, 52, 137–167. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831214549448

Carpenter, D. (2015). School culture and leadership of professional learning communities. International Journal of Educational Management, 29 (5), 682–694. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-04-2014-0046

Carrington, S., & Elkins, J. (2002). Bridging the gap between inclusive policy and inclusive culture in secondary schools. Support for Learning, 17 (2), 51–57.

Carter, S., & Abawi, L. (2018). Leadership, inclusion, and quality education for all. Australasian Journal of Special and Inclusive Education, 42 (1), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.1017/jsi.2018.5

CAST. (2018). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines Version 2.2. http://udlguidelines.cast.org

Davies, M., Elliott, S., & Cumming, J. (2016). Documenting support needs and adjustment gaps for students with disabilities: Teacher practices in Australian classrooms and on national tests. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20 (12), 1252–1269. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2016.1159256

Desimone, L. M. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: Toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educational Researcher, 38 (3),181–199. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X08331140

Desimone, L. M., & Pak, K. (2017). Instructional coaching as high-quality professional development. Theory Into Practice, 56 (1), 312. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2016.1241947

Dixon, F. A., Yssel, N., McConnell, J. A., & Hardin, T. (2014). Differentiated instruction, professional development and teacher efficacy. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 37 (2), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162353214529042

Dybvik, A. C. (2004). Autism and the inclusion mandate: What happens when children with severe disabilities like autism are taught in regular classrooms? Daniel knows. Education Next, 4 (1), 42–49.

Dyson, A., Farrell, P., Polat, F., Hutcheson, G., & Gallanaugh, F. (2004). Inclusion and pupil achievement. Department for Education and Skills.

Easton, L. B. (2008). From professional development to professional learning. Phi Delta Kappan, 89, 755–761. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172170808901014

Ekins, A., & Grimes, P. (2009). Inclusion: Developing an Effective Whole School Approach. McGraw Hill Open University Press.

Forlin, C. (2006). Inclusive education in Australia ten years after Salamanca. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 21 (3), 265–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03173415

Forlin, C., & Chambers, D. (2011). Teacher preparation for inclusive education: Increasing knowledge but raising concerns. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 39 (1), 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2010.540850

Forlin, C., Chambers, D. J., Loreman, T., Deppler, J., & Sharma, U. (2013). Inclusive education for students with disability: A review of the best evidence in relation to theory and practice. The Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth. https://www.aracy.org.au/publicationsresources/command/download_file/id/246/filename/Inclusive_education_for_students_with_disability_-_A_review_of_the_best_evidence_in_relation_to_theory_and_practice.pdf73

Forlin, C., Keen, M., & Barrett. E. (2008). The concerns of mainstream teachers: Coping with inclusivity in an Australian context. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 55 (3), 251–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/10349120802268396

Frankling, T. W., Jarvis, J. M. & Bell. M. R. (2017). Leading secondary teachers’ understandings and practices of differentiation through professional learning. Leading and Managing, 23 (2), 72–86.

Fuchs, D., Fuchs, L. S., & Stecker, P. M. (2010). The ‘blurring’ of special education in a new continuum of general education placements and services. Exceptional Children, 76 (3), 301–323. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440291007600304

Gore, J., Lloyd, A., Smith, M., Bowe, J., Ellis, H., & Lubans, D. (2017). Effects of professional development on the quality of teaching: Results from a randomised controlled trial of Quality Teaching Rounds. Teaching and Teacher Education, 68, 91–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.08.007

Graham, L., & Spandagou, I. (2011). From vision to reality: Views of primary school principals on inclusive education in New South Wales, Australia. Disability & Society, 26 (2), 223–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2011.544062

Grierson, A. L., & Woloshyn, V. E. (2013). Walking the talk: Supporting teachers’ growth with differentiated professional learning. Professional Development in Education, 39 (3), 401–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2012.763143

Guskey, T. R. (2000). Evaluating professional development. Corwin Press

Harris, A. (2013). Distributed leadership: Friend or foe? Educational Management, Administration & Leadership, 4 (5), 545–554. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143213497635

Hehir, T., Pascucci, S., & Pascucci, C. (2016). A summary of the evidence on inclusive education, Instituto Alana, 2. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED596134.pdf

Horrocks, J. L., White, G., & Roberts, L. (2008). Principals' attitudes regarding inclusion of children with autism in Pennsylvania public schools. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 1462–1473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-007-0522-x

Jarvis, J. M. (2015). Inclusive Classrooms and Differentiation. In N. Weatherby-Fell (Ed.), Learning to Teach in the Secondary School (pp. 154–171). Cambridge University Press.

Jarvis, J. M. (2019). Most Australian teachers feel unprepared to teach students with special needs. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/most-australian-teachers-feel-unpreparedto-teach-students-with-special-needs-119227

Jarvis, J. M., (2017). Supporting diverse gifted students. In M. Hyde, L. Carpenter & S. Dole (Eds.), Diversity, Inclusion and Engagement (3rd ed., pp. 308–329). Oxford University Press.

Johnston, K., & Hayes, D. (2007). Supporting students’ success at school through teacher professional learning: The pedagogy of disrupting the default modes of schooling. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 11 (3), 371–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110701240666

Kinsella, W. (2020). Organising inclusive schools. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24 (12), 1340–1356. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1516820

Kozik, P., Cooney, B., Vinciguerra, S., Gradel, K., & Black, J. (2009). Promoting inclusion in secondary schools through appreciative inquiry. American Secondary Education, 38 (1), 77–91.

McLeskey, J., Waldron, N. L., Spooner, F., & Algozzine, B. (Eds.). (2014). Handbook of effective inclusive schools: Research and practice. Taylor & Francis.

McMaster, C. (2013). Building inclusion from the ground up: A review of whole school re-culturing programmes for sustaining inclusive change. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 9 (2), 1–24.

McMaster, C. (2015). Inclusion in New Zealand: The potential and possibilities of sustainable inclusive change through utilising a framework for whole school development. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 50 (2), 239–253.

McMaster, C., & Elliot, W. (2014). Leading inclusive change with the Index for Inclusion: Using a framework to manage sustainable professional development. Journal of Educational Leadership, Policy and Practice, 29 (1), 82–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-015-0010-3

McMillan, J., & Jarvis, J. M. (2017). Supporting mental health and well-being: Promotion, prevention and intervention. In M. Hyde, L. Carpenter & S. Dole (Eds.), Diversity, inclusion and engagement (3rd ed., pp. 65–392). Oxford University Press.

Merchie, E., Tuytens, M., Devos, G., & Vanderlinde, R. (2018). Evaluating teachers’ professional development initiatives: Towards an extended evaluative framework. Research Papers in Education, 33 (2), 143–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2016.1271003

Mills, M., Monk, S., Keddie, A., Renshaw, P., Christie, P., Geelan, D. & C. Gowlett, C. (2014). Differentiated learning: From policy to classroom. Oxford Review of Education, 40 (3), 331–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2014.911725

Miškolci, J., Armstrong, D., & Spandagou, I. (2016). Teachers' perceptions of the relationship between inclusive education and distributed leadership in two primary schools in Slovakia and New South Wales (Australia). Journal of Teacher Education for Sustainability, 18 (2), 53–65. https://doi.org/10.1515/jtes-2016-001

Mullick, J., Sharma, U., & Deppeler, J. (2013). School teachers' perception about distributed leadership practices for inclusive education in primary schools in Bangladesh. School Leadership & Management, 33 (2), 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2012.723615

OECD (2019). TALIS 2018 Results (Volume I): Teachers and School Leaders as Lifelong Learners. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/1d0bc92a-en.

Parliament of South Australia. (2017). Report of the select committee on access to the South Australian Education System for students with a disability. https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2017-05/apo-nid94396.pdf

Poon-McBrayer, K., & Wong, P. (2013). Inclusive education services for children and youth with disabilities: Values, roles and challenges of school leaders. Children and Youth Services Review, 35 (9), 1520–1525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.06.009

Read, K., Aldridge, J., Ala’i, K., Fraser, B., & Fozdar, F. (2015). Creating a climate in which students can flourish: A whole school intercultural approach. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 11 (2), 29–44. https://doi.org/1710-2146

Robinson, V. M. J., Lloyd, C. A., & Rowe, K. J. (2008). The impact of leadership on student outcomes: An analysis of the differential effects of leadership types. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44 (5), 635–674. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X08321509

Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability. (2019). Issues Paper: Education and Learning. https://disability.royalcommission.gov.au/system/files/2020-07/Issues-paper-Education-Learning.pdf

Sailor, W. (2015). Advances in schoolwide inclusive school reform. Remedial and Special Education, 36, 94–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932514555021

Sailor, W. (2017). Equity as a basis for inclusive educational systems change. The Australasian Journal of Special Education, 41 (1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/jse.2016.12

Schein, E. (2004). Organizational culture and leadership (3rd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Sharma, U., & Salend, S. (2016). Teaching assistants in inclusive classrooms: A systematic analysis of the international research. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 41 (8), 118–134.

Sharp, K., Jarvis, J. M., & McMillan, J. M. (2020). Leadership for differentiated instruction: Teachers' engagement with on-site professional learning at an Australian secondary school. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24 (8), 901–920. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1492639

Skidmore, D. (2004). Inclusion: The dynamic of school development. McGraw-Hill Education.

Slater, C. L. (2012). Understanding principal leadership: An international perspective and a narrative approach. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 39 (2), 219–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143210390061

Slee, R. (2013). How do we make inclusive education happen when exclusion is a political predisposition? International Journal of Inclusive Education: Making Inclusive Education Happen: Ideas for Sustainable Change, 17 (8), 895–907. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2011.602534

Spencer, E. J. (2016). Professional learning communities: Keeping the focus on instructional practice. Kappa Delta Pi Record, 52 (2), 83–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/00228958.2016.1156544

Stegemann, K., & Jaciw, A. (2018). Making it logical: Implementation of inclusive education using a logic model framework. Learning Disabilities: A Contemporary Journal, 16 (1), 3–18.

Symes, W., & Humphrey, N. (2011). School factors that facilitate or hinder the ability of teaching assistants to effectively support pupils with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) in mainstream secondary schools. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 11 (3), 153–161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2011.01196.x

Thomas, G. (2013). A review of thinking and research about inclusive education policy, with suggestions for a new kind of inclusive thinking. British Educational Research Journal, 39 (3), 473–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411926.2011.652070

Tomlinson, C. A. (2014). The differentiated classroom: Responding to the needs of all learners (2nd ed.). Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Tomlinson, C. A., & Murphy, M. (2015). Leading for differentiation: Growing teachers who grow kids. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Tomlinson, C.A., Brimijoin, K., & Narvaez, L. (2008). The differentiated school: Making revolutionary changes in teaching and learning. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Van Den Bergh, L., Ros, A., & Beijaard, D. (2014). Improving teacher feedback during active learning: Effects of a professional development program. American Educational Research Journal, 51 (4), 772–809. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831214531322

van Kraayenoord, C. E. (2007). School and classroom practices in inclusive education in Australia. Childhood Education, 83 (6), 390–394, https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.2007.10522957

van Kraayenoord, C. E., Waterworth, D., & Brady. T. (2014). Responding to individual differences in inclusive classrooms in Australia. Journal of International Special Needs Education, 17 (2), 48–59.

Van Mieghem, A., Verschueren, K., Petry, K., & Struyf, E. (2020). An analysis of research on inclusive education: A systematic search and meta review. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 26 (6), 675–689. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1482012

Voelkel, R. H., Jr., & Chrispeels, J. H. (2017). Understanding the link between professional learning communities and teacher collective efficacy. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 28, 505–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2017.1299015

Waitoller, F. R., & Artiles, A. J. (2013). A decade of professional development research for inclusive education: A critical review and notes for a research program. Review of Educational Research, 83 (3), 319–356. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654313483905

Walker, P. M., Carson, K. L., Jarvis, J. M., McMillan, J. M., Noble, A. G., Armstrong, D., . . . Palmer, C. (2018). How do educators of students with disabilities in specialist settings understand and apply the Australian Curriculum framework? Australasian Journal of Special and Inclusive Education, 42 (2), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1017/jsi.2018.13

Webster, A. (2016). Utilising a leadership blueprint to build the capacity of schools to achieve outcomes for students with autism spectrum disorder. In G. Johnson & N. Dempster (Eds.), Leadership in diverse learning contexts (pp. 109–127). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28302-9_6

Whitworth, B. A., & Chiu, J. L. (2015). Professional development and teacher change: The missing leadership link. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 26 (2), 121–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10972-014-9411-2

Inclusive School Communities Project Phone: (08) 8373 8333 Email: [email protected] Address: 104 Greenhill Road, Unley SA 5061

- Open access

- Published: 14 May 2024

Protocol for a scoping review study on learning plan use in undergraduate medical education

- Anna Romanova ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1118-1604 1 ,

- Claire Touchie 1 ,

- Sydney Ruller 2 ,

- Victoria Cole 3 &

- Susan Humphrey-Murto 4

Systematic Reviews volume 13 , Article number: 131 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

The current paradigm of competency-based medical education and learner-centredness requires learners to take an active role in their training. However, deliberate and planned continual assessment and performance improvement is hindered by the fragmented nature of many medical training programs. Attempts to bridge this continuity gap between supervision and feedback through learner handover have been controversial. Learning plans are an alternate educational tool that helps trainees identify their learning needs and facilitate longitudinal assessment by providing supervisors with a roadmap of their goals. Informed by self-regulated learning theory, learning plans may be the answer to track trainees’ progress along their learning trajectory. The purpose of this study is to summarise the literature regarding learning plan use specifically in undergraduate medical education and explore the student’s role in all stages of learning plan development and implementation.

Following Arksey and O’Malley’s framework, a scoping review will be conducted to explore the use of learning plans in undergraduate medical education. Literature searches will be conducted using multiple databases by a librarian with expertise in scoping reviews. Through an iterative process, inclusion and exclusion criteria will be developed and a data extraction form refined. Data will be analysed using quantitative and qualitative content analyses.

By summarising the literature on learning plan use in undergraduate medical education, this study aims to better understand how to support self-regulated learning in undergraduate medical education. The results from this project will inform future scholarly work in competency-based medical education at the undergraduate level and have implications for improving feedback and supporting learners at all levels of competence.

Scoping review registration:

Open Science Framework osf.io/wvzbx.

Peer Review reports

Competency-based medical education (CBME) has transformed the approach to medical education to focus on demonstration of acquired competencies rather than time-based completion of rotations [ 1 ]. As a result, undergraduate and graduate medical training programs worldwide have adopted outcomes-based assessments in the form of entrustable professional activities (EPAs) comprised of competencies to be met [ 2 ]. These assessments are completed longitudinally by multiple different evaluators to generate an overall impression of a learner’s competency.

In CBME, trainees will progress along their learning trajectory at individual speeds and some may excel while others struggle to achieve the required knowledge, skills or attitudes. Therefore, deliberate and planned continual assessment and performance improvement is required. However, due to the fragmented nature of many medical training programs where learners rotate through different rotations and work with many supervisors, longitudinal observation is similarly fragmented. This makes it difficult to determine where trainees are on their learning trajectories and can affect the quality of feedback provided to them, which is a known major influencer of academic achievement [ 3 ]. As a result, struggling learners may not be identified until late in their training and the growth of high-performing learners may be stifled [ 4 , 5 , 6 ].

Bridging this continuity gap between supervision and feedback through some form of learner handover or forward feeding has been debated since the 1970s and continues to this day [ 5 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ]. The goal of learner handover is to improve trainee assessment and feedback by sharing their performance and learning needs between supervisors or across rotations. However, several concerns have been raised about this approach including that it could inappropriately bias subsequent assessments of the learner’s abilities [ 9 , 11 , 12 ]. A different approach to keeping track of trainees’ learning goals and progress along their learning trajectories is required. Learning plans (LPs) informed by self-regulated learning (SRL) theory may be the answer.

SRL has been defined as a cyclical process where learners actively control their thoughts, actions and motivation to achieve their goals [ 13 ]. Several models of SRL exist but all entail that the trainee is responsible for setting, planning, executing, monitoring and reflecting on their learning goals [ 13 ]. According to Zimmerman’s SRL model, this process occurs in three stages: forethought phase before an activity, performance phase during an activity and self-reflection phase after an activity [ 13 ]. Since each trainee leads their own learning process and has an individual trajectory towards competence, this theory relates well to the CBME paradigm which is grounded in learner-centredness [ 1 ]. However, we know that medical students and residents have difficulty identifying their own learning goals and therefore need guidance to effectively partake in SRL [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ]. Motivation has also emerged as a key component of SRL, and numerous studies have explored factors that influence student engagement in learning [ 18 , 19 ]. In addition to meeting their basic psychological needs of autonomy, relatedness and competence, perceived learning relevance through meaningful learning activities has been shown to increase trainee engagement in their learning [ 19 ].

LPs are a well-known tool across many educational fields including CBME that can provide trainees with meaningful learning activities since they help them direct their own learning goals in a guided fashion [ 20 ]. Also known as personal learning plans, learning contracts, personal action plans, personal development plans, and learning goals, LPs are documents that outline the learner’s roadmap to achieve their learning goals. They require the learner to self-identify what they need to learn and why, how they are going to do it, how they will know when they are finished, define the timeframe for goal achievement and assess the impact of their learning [ 20 ]. In so doing, LPs give more autonomy to the learner and facilitate objective and targeted feedback from supervisors. This approach has been described as “most congruent with the assumptions we make about adults as learners” [ 21 ].

LP use has been explored across various clinical settings and at all levels of medical education; however, most of the experience lies in postgraduate medical education [ 22 ]. Medical students are a unique learner population with learning needs that appear to be very well suited for using LPs for two main reasons. First, their education is often divided between classroom and clinical settings. During clinical training, students need to be more independent in setting learning goals to meet desired competencies as their education is no longer outlined for them in a detailed fashion by the medical school curriculum [ 23 ]. SRL in the workplace is also different than in the classroom due to additional complexities of clinical care that can impact students’ ability to self-regulate their learning [ 24 ]. Second, although most medical trainees have difficulty with goal setting, medical students in particular need more guidance compared to residents due to their relative lack of experience upon which they can build within the SRL framework [ 25 ]. LPs can therefore provide much-needed structure to their learning but should be guided by an experienced tutor to be effective [ 15 , 24 ].

LPs fit well within the learner-centred educational framework of CBME by helping trainees identify their learning needs and facilitating longitudinal assessment by providing supervisors with a roadmap of their goals. In so doing, they can address current issues with learner handover and identification as well as remediation of struggling learners. Moreover, they have the potential to help trainees develop lifelong skills with respect to continuing professional development after graduation which is required by many medical licensing bodies.

An initial search of the JBI Database, Cochrane Database, MEDLINE (PubMed) and Google Scholar conducted in July–August 2022 revealed a paucity of research on LP use in undergraduate medical education (UGME). A related systematic review by van Houten–Schat et al. [ 24 ] on SRL in the clinical setting identified three interventions used by medical students and residents in SRL—coaching, LPs and supportive tools. However, only a couple of the included studies looked specifically at medical students’ use of LPs, so this remains an area in need of more exploration. A scoping review would provide an excellent starting point to map the body of literature on this topic.

The objective of this scoping review will therefore be to explore LP use in UGME. In doing so, it will address a gap in knowledge and help determine additional areas for research.

This study will follow Arksey and O’Malley’s [ 26 ] five-step framework for scoping review methodology. It will not include the optional sixth step which entails stakeholder consultation as relevant stakeholders will be intentionally included in the research team (a member of UGME leadership, a medical student and a first-year resident).

Step 1—Identifying the research question

The overarching purpose of this study is to “explore the use of LPs in UGME”. More specifically we seek to achieve the following:

Summarise the literature regarding the use of LPs in UGME (including context, students targeted, frameworks used)

Explore the role of the student in all stages of the LP development and implementation

Determine existing research gaps

Step 2—Identifying relevant studies

An experienced health sciences librarian (VC) will conduct all searches and develop the initial search strategy. The preliminary search strategy is shown in Appendix A (see Additional file 2). Articles will be included if they meet the following criteria [ 27 ]:

Participants

Medical students enrolled at a medical school at the undergraduate level.

Any use of LPs by medical students. LPs are defined as a document, usually presented in a table format, that outlines the learner’s roadmap to achieve their learning goals [ 20 ].

Any stage of UGME in any geographic setting.

Types of evidence sources

We will search existing published and unpublished (grey) literature. This may include research studies, reviews, or expert opinion pieces.

Search strategy

With the assistance of an experienced librarian (VC), a pilot search will be conducted to inform the final search strategy. A search will be conducted in the following electronic databases: MEDLINE, Embase, Education Source, APA PsycInfo and Web of Science. The search terms will be developed in consultation with the research team and librarian. The search strategy will proceed according to the JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis three-step search strategy for reviews [ 27 ]. First, we will conduct a limited search in two appropriate online databases and analyse text words from the title, abstracts and index terms of relevant papers. Next, we will conduct a second search using all identified key words in all databases. Third, we will review reference lists of all included studies to identify further relevant studies to include in the review. We will also contact the authors of relevant papers for further information if required. This will be an iterative process as the research team becomes more familiar with the literature and will be guided by the librarian. Any modifications to the search strategy as it evolves will be described in the scoping review report. As a measure of rigour, the search strategy will be peer-reviewed by another librarian using the PRESS checklist [ 28 ]. No language or date limits will be applied.

Step 3—Study selection

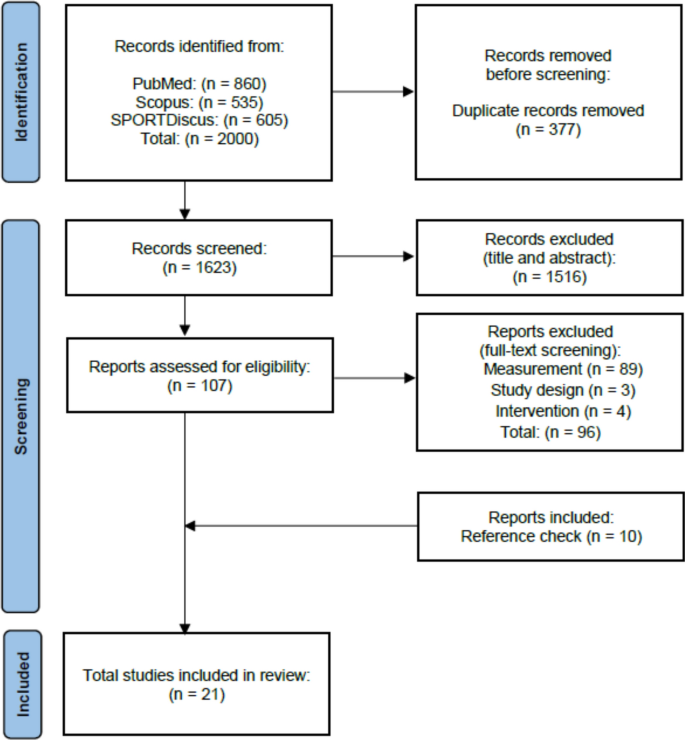

The screening process will consist of a two-step approach: screening titles/abstracts and, if they meet inclusion criteria, this will be followed by a full-text review. All screening will be done by two members of the research team and any disagreements will be resolved by an independent third member of the team. Based on preliminary inclusion criteria, the whole research team will first pilot the screening process by reviewing a random sample of 25 titles/abstracts. The search strategy, eligibility criteria and study objectives will be refined in an iterative process. We anticipate several meetings as the topic is not well described in the literature. A flowchart of the review process will be generated. Any modifications to the study selection process will be described in the scoping review report. The papers will be excluded if a full text is not available. The search results will be managed using Covidence software.

Step 4—Charting the data

A preliminary data extraction tool is shown in Appendix B (see Additional file 3 ). Data will be extracted into Excel and will include demographic information and specific details about the population, concept, context, study methods and outcomes as they relate to the scoping review objectives. The whole research team will pilot the data extraction tool on ten articles selected for full-text review. Through an iterative process, the final data extraction form will be refined. Subsequently, two members of the team will independently extract data from all articles included for full-text review using this tool. Charting disagreements will be resolved by the principal and senior investigators. Google Translate will be used for any included articles that are not in the English language.

Step 5—Collating, summarising and reporting the results

Quantitative and qualitative analyses will be used to summarise the results. Quantitative analysis will capture descriptive statistics with details about the population, concept, context, study methods and outcomes being examined in this scoping review. Qualitative content analysis will enable interpretation of text data through the systematic classification process of coding and identifying themes and patterns [ 29 ]. Several team meetings will be held to review potential themes to ensure an accurate representation of the data. The PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) will be used to guide the reporting of review findings [ 30 ]. Data will be presented in tables and/or diagrams as applicable. A descriptive summary will explain the presented results and how they relate to the scoping review objectives.

By summarising the literature on LP use in UGME, this study will contribute to a better understanding of how to support SRL amongst medical students. The results from this project will also inform future scholarly work in CBME at the undergraduate level and have implications for improving feedback as well as supporting learners at all levels of competence. In doing so, this study may have practical applications by informing learning plan incorporation into CBME-based curricula.

We do not anticipate any practical or operational issues at this time. We assembled a team with the necessary expertise and tools to complete this project.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study will be included in the published scoping review article.

Abbreviations

- Competency-based medical education

Entrustable professional activity

- Learning plan

- Self-regulated learning

- Undergraduate medical education

Frank JR, Snell LS, Cate OT, et al. Competency-based medical education: theory to practice. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):638–45.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Shorey S, Lau TC, Lau ST, Ang E. Entrustable professional activities in health care education: a scoping review. Med Educ. 2019;53(8):766–77.

Hattie J, Timperley H. The power of feedback. Rev Educ Res. 2007;77(1):81–112.

Article Google Scholar

Dudek NL, Marks MB, Regehr G. Failure to fail: the perspectives of clinical supervisors. Acad Med. 2005;80(10 Suppl):S84–7.

Warm EJ, Englander R, Pereira A, Barach P. Improving learner handovers in medical education. Acad Med. 2017;92(7):927–31.

Spooner M, Duane C, Uygur J, et al. Self-regulatory learning theory as a lens on how undergraduate and postgraduate learners respond to feedback: a BEME scoping review : BEME Guide No. 66. Med Teach. 2022;44(1):3–18.

Frellsen SL, Baker EA, Papp KK, Durning SJ. Medical school policies regarding struggling medical students during the internal medicine clerkships: results of a National Survey. Acad Med. 2008;83(9):876–81.

Humphrey-Murto S, LeBlanc A, Touchie C, et al. The influence of prior performance information on ratings of current performance and implications for learner handover: a scoping review. Acad Med. 2019;94(7):1050–7.

Morgan HK, Mejicano GC, Skochelak S, et al. A responsible educational handover: improving communication to improve learning. Acad Med. 2020;95(2):194–9.

Dory V, Danoff D, Plotnick LH, et al. Does educational handover influence subsequent assessment? Acad Med. 2021;96(1):118–25.

Humphrey-Murto S, Lingard L, Varpio L, et al. Learner handover: who is it really for? Acad Med. 2021;96(4):592–8.

Shaw T, Wood TJ, Touchie T, Pugh D, Humphrey-Murto S. How biased are you? The effect of prior performance information on attending physician ratings and implications for learner handover. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2021;26(1):199–214.

Artino AR, Brydges R, Gruppen LD. Chapter 14: Self-regulated learning in health professional education: theoretical perspectives and research methods. In: Cleland J, Duning SJ, editors. Researching Medical Education. 1st ed. John Wiley & Sons; 2015. p. 155–66.

Chapter Google Scholar

Cleland J, Arnold R, Chesser A. Failing finals is often a surprise for the student but not the teacher: identifying difficulties and supporting students with academic difficulties. Med Teach. 2005;27(6):504–8.

Reed S, Lockspeiser TM, Burke A, et al. Practical suggestions for the creation and use of meaningful learning goals in graduate medical education. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(1):20–4.

Wolff M, Stojan J, Cranford J, et al. The impact of informed self-assessment on the development of medical students’ learning goals. Med Teach. 2018;40(3):296–301.

Sawatsky AP, Halvorsen AJ, Daniels PR, et al. Characteristics and quality of rotation-specific resident learning goals: a prospective study. Med Educ Online. 2020;25(1):1714198.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Pintrich PR. Chapter 14: The role of goal orientation in self-regulated learning. In: Boekaerts M, Pintrich PR, Zeidner M, editors. Handbook of self-regulation. 1st ed. Academic Press; 2000. p. 451–502.

Kassab SE, El-Sayed W, Hamdy H. Student engagement in undergraduate medical education: a scoping review. Med Educ. 2022;56(7):703–15.

Challis M. AMEE medical education guide No. 19: Personal learning plans. Med Teach. 2000;22(3):225–36.

Knowles MS. Using learning contracts. 1 st ed. San Francisco: Jossey Bass; 1986.

Parsell G, Bligh J. Contract learning, clinical learning and clinicians. Postgrad Med J. 1996;72(847):284–9.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Teunissen PW, Scheele F, Scherpbier AJJA, et al. How residents learn: qualitative evidence for the pivotal role of clinical activities. Med Educ. 2007;41(8):763–70.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

van Houten-Schat MA, Berkhout JJ, van Dijk N, Endedijk MD, Jaarsma ADC, Diemers AD. Self-regulated learning in the clinical context: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2018;52(10):1008–15.

Taylor DCM, Hamdy H. Adult learning theories: Implications for learning and teaching in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 83. Med Teach. 2013;35(11):e1561–72.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco AC, Khalol H. Chapter 11: Scoping reviews. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, eds. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI; 2020. https://synthesismanual.jbi.global. . Accessed 30 Aug 2022.

McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40–6.

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Venables M, Larocque A, Sikora L, Archibald D, Grudniewicz A. Understanding indigenous health education and exploring indigenous anti-racism approaches in undergraduate medical education: a scoping review protocol. OSF; 2022. https://osf.io/umwgr/ . Accessed 26 Oct 2022.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

This study will be supported through grants from the Department of Medicine at the Ottawa Hospital and the University of Ottawa. The funding bodies had no role in the study design and will not have any role in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data or writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

The Ottawa Hospital – General Campus, 501 Smyth Rd, PO Box 209, Ottawa, ON, K1H 8L6, Canada

Anna Romanova & Claire Touchie

The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada

Sydney Ruller

The University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

Victoria Cole

The Ottawa Hospital – Riverside Campus, Ottawa, Canada

Susan Humphrey-Murto

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

AR designed and drafted the protocol. CT and SH contributed to the refinement of the research question, study methods and editing of the manuscript. VC designed the initial search strategy. All authors reviewed the manuscript for final approval. The review guarantors are CT and SH. The corresponding author is AR.

Authors’ information

AR is a clinician teacher and Assistant Professor with the Division of General Internal Medicine at the University of Ottawa. She is also the Associate Director for the internal medicine clerkship rotation at the General campus of the Ottawa Hospital.

CT is a Professor of Medicine with the Divisions of General Internal Medicine and Infectious Diseases at the University of Ottawa. She is also a member of the UGME Competence Committee at the University of Ottawa and an advisor for the development of a new school of medicine at Toronto Metropolitan University.

SH is an Associate Professor with the Department of Medicine at the University of Ottawa and holds a Tier 2 Research Chair in Medical Education. She is also the Interim Director for the Research Support Unit within the Department of Innovation in Medical Education at the University of Ottawa.

CT and SH have extensive experience with medical education research and have numerous publications in this field.

SR is a Research Assistant with the Division of General Internal Medicine at the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute.

VC is a Health Sciences Research Librarian at the University of Ottawa.

SR and VC have extensive experience in systematic and scoping reviews.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Anna Romanova .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. prisma-p 2015 checklist., 13643_2024_2553_moesm2_esm.docx.

Additional file 2: Appendix A. Preliminary search strategy [ 31 ].

Additional file 3: Appendix B. Preliminary data extraction tool.

Rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Romanova, A., Touchie, C., Ruller, S. et al. Protocol for a scoping review study on learning plan use in undergraduate medical education. Syst Rev 13 , 131 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-024-02553-w

Download citation

Received : 29 November 2022

Accepted : 03 May 2024

Published : 14 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-024-02553-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.