- University of Texas Libraries

Literature Reviews

Steps in the literature review process.

- What is a literature review?

- Define your research question

- Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Choose databases and search

- Review Results

- Synthesize Results

- Analyze Results

- Librarian Support

- You may need to some exploratory searching of the literature to get a sense of scope, to determine whether you need to narrow or broaden your focus

- Identify databases that provide the most relevant sources, and identify relevant terms (controlled vocabularies) to add to your search strategy

- Finalize your research question

- Think about relevant dates, geographies (and languages), methods, and conflicting points of view

- Conduct searches in the published literature via the identified databases

- Check to see if this topic has been covered in other discipline's databases

- Examine the citations of on-point articles for keywords, authors, and previous research (via references) and cited reference searching.

- Save your search results in a citation management tool (such as Zotero, Mendeley or EndNote)

- De-duplicate your search results

- Make sure that you've found the seminal pieces -- they have been cited many times, and their work is considered foundational

- Check with your professor or a librarian to make sure your search has been comprehensive

- Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of individual sources and evaluate for bias, methodologies, and thoroughness

- Group your results in to an organizational structure that will support why your research needs to be done, or that provides the answer to your research question

- Develop your conclusions

- Are there gaps in the literature?

- Where has significant research taken place, and who has done it?

- Is there consensus or debate on this topic?

- Which methodological approaches work best?

- For example: Background, Current Practices, Critics and Proponents, Where/How this study will fit in

- Organize your citations and focus on your research question and pertinent studies

- Compile your bibliography

Note: The first four steps are the best points at which to contact a librarian. Your librarian can help you determine the best databases to use for your topic, assess scope, and formulate a search strategy.

Videos Tutorials about Literature Reviews

This 4.5 minute video from Academic Education Materials has a Creative Commons License and a British narrator.

Recommended Reading

- Last Updated: Oct 26, 2022 2:49 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/literaturereviews

- Open access

- Published: 05 March 2013

Activity-based costing in services: literature bibliometric review

- Nara Medianeira Stefano 1 &

- Nelson Casarotto Filho 1

SpringerPlus volume 2 , Article number: 80 ( 2013 ) Cite this article

20k Accesses

9 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

This article is aimed at structuring a bibliography portfolio to treat the application of the ABC method in service and contribute to discussions within the scientific community. The methodology followed a three-stage procedure: Planning, execution and Synthesis. Also, the process ProKnow-C (Knowledge Process Development - Constructivist) was used in the execution stage. International databases were used to collect information (ISI Web of Knowledge and Scopus). As a result, we obtained a bibliography portfolio of 21 articles (with scientific recognition) dealing with the proposed theme.

Introduction

Managers need certain information to improve the efficiency of their management. They also lack answers to two very important questions: what are the sources of profitability, and how can the organization's performance be improved? Managers cannot make decisions without reliable information about costs, so the need to calculate product costs or services through the Activity-Based Costing (ABC) is emphasized.

The ABC method has the fundamental characteristic to seek to reduce distortions caused by arbitrary allotment of indirect costs acquired in traditional systems. Indeed, ABC is one of the methods made and published about the application of this method (Gunasekaran et al., 1999 ; Hussain and Guanasekaran 2001 ; Cotton et al., 2003 ; Kellermanns and Islam, 2004 ; Kallunki and Silvola, 2008 ; Duh et al., 2009 ; Dugel and Bianchini, 2011 ; Stefano, 2011 ; Lutilsky and Dragija, 2012 ; Jänkälä and Silvola, 2012 ; Schulze et al., 2012 ).

The ABC approach treats the client as the object of cost analysis, in parallel with the analysis of ownership costs for suppliers (Niraj et al., 2001 ; Narayanan and Sarkar, 2002 ; Anderson, 2005 ; Salem-Mhamdia and Ghadhab 2012 ). The emphasis is on getting a better understanding of the behavior of indirect costs. The ABC system is designed and implemented on the premise that products consume activities, activities consume resources and resources consume costs. Thus, the terms activities, drivers and resources are important for understanding ABC.

An activity is the result of the combination of technological and financial material and human resources used to produce goods and services. The cost driver is the way in which costs are assigned to activities, they form the basis of ABC, and seek to trace the origin of the cost and establish a relationship of cause/effect (Stefano et al., 2010 ). Resources or inputs are necessary expenses, arising from regular operations of the organization, such as depreciation, water, wages and electricity. The amount of each driver that is associated with the activity that you want to cover is called a factor of resource consumption.

With economic development and increased competitiveness, the services sector began to look for new concepts in management, so it could monitor the market, increasingly demanding. Despite the different characteristics in relation to the manufacturing (Gunasekaran and Sarhadi, 1998 ) sector, it has been seeking and adapting concepts used successfully in the cost area.

The current economic climate meant that the service organizations feel the need to know, control and manage their costs effectively. Hence, the importance of investing in programs aimed at reducing production costs. Expenses that with some care, could often be easily prevented or at least reduced, often turn out to link the final cost of products and/or services. In general, the cost controls in service organizations have some points in common with those practiced in the industry. Such issues are production order (Lins and Silva, 2005 ), contribution margin and balance point, and can be applied in many service organizations.

Therefore, within this context, the aim of this article is to structure a bibliography portfolio to check the use of the ABC method in service (Susskind, 2010 ; Büyüközkan et al. 2011 ; Büyüközkan and Çifçi 2012 ; Grissemann and Stokburger-Sauer, 2012 ; Gunasekaran and Spalanzani 2012 ; Calabrese, 2012 ) and contribute to discussions within the scientific community. The methodological approach used was a literature review based on bibliometrics (Førsund and Sarafoglou 2005 ; Tsai, 2011 ; Tan et al., 2010 ; Tsay and Zhu-yee 2011 ; Gumpenberger et al., 2012 ; Van Raan, 2012 ) and qualitative and quantitative analysis of the articles. The databases chosen to select the publications was portal ISI Web of Knowledge e Scopus for being comprehensive and multidisciplinary (and can be accessed via the portal Capes), and period of searches comprises 1990–2011. The methodology followed a three-stage procedure: planning, execution and reporting. Process ProKnow -C ( Knowledge Process Development - Constructivist ) was also used in the stage of execution.

Besides this introduction, the paper presents: (i) research methodology, (ii) results; (iii) the results and (iv) final considerations; and, finally, (v) references used.

Research methodology

This section discusses choice procedures and methodology description.

Methodology choice

An analytical review is necessary to systematically assess the contribution of a particular literature topic. Generally, the review process consists of three parts: data collection, data analysis and data synthesis. The scientific rigor in the conduct of each of these steps is critical to an analysis of its quality. Data collection can be done in different ways. As an example, using existing knowledge in the literature to select articles and search various databases using keywords.

Once items are selected for review, data analysis can proceed in different ways, depending on the objectives of the revision (Crossan and Apaydin, 2010 ). A review to consolidate the results of several empirical studies may depend on either qualitative or quantitative analysis of the results. Data synthesis is the main product of the research as it produces new knowledge based on complete data collection.

This research is exploratory and descriptive (Richardson 2008 ). It is exploratory because it follows a process to build a bibliographic portfolio of articles in a given topic. It is descriptive because it seeks to describe the characteristics of scientific publications of this portfolio and its references, in case, the application of ABC method of costs in services.

Methodology description

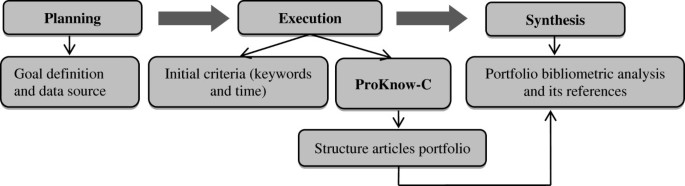

For this paper a three-stage procedure was followed: Planning, Implementation and Synthesis (Figure 1 ). During the planning phase, the research objectives were defined and the sources of data were identified. The second stage, implementation, consists of two sub-steps: identifying the initial selection criteria (time, databases and keywords) and using the ProKnow -C ( Knowledge Development Process–Constructivist ).

Proposed structure for the paper. Source: Authors.

ProKnow-C is proposed by Ensslin et al. ( 2010 ) to build knowledge based on a researcher’s interests and boundaries, according to the constructivist view. This instrument (Bortoluzzi et al., 2011 ), provides the steps to be followed for the construction of a Bibliographic Portfolio selection representing the topic that you want to search. This phase is divided into two steps: (a) Selection of gross articles stock (2) filtering the stock items, which is secreted into five sub-steps: (a) gross articles stock filter regarding redundancy; (b) non-recurrent gross articles stock filter regarding title alignment, (c) non-recurrent gross articles stock filter with title alignment regarding scientific recognition, and (d) article reanalysis process that do not have science recognition, (e) filter regarding complete article alignment.

The third and last step concerns the synthesis that is the portfolio bibliometric analysis and its references. It was chosen to be limited only to journals as data sources because they can be considered validated knowledge and are likely to have greater impact. Articles published in conferences and seminars were not considered, as well as books, dissertations and theses. ISI “Web of Knowledge” and Scopus databases were chosen because the databases are comprehensive and multidisciplinary. Interesting, the characteristic of these bases is that they have the scores of citations of articles, and this allows a screening of a series of articles based on this criterion.

The number of times an article is cited in Google Scholar was considered, for in ISI Web of Knowledge and Scopus only the journals or databases within it counted and not all the bases where this article is. For example, the article Improving hospital cost accounting with activity-based costing on 13/03/2012, shows that its citation number is 59, in Scopus. Now, when we use the same article and check it on Google Scholar , the number of citations shown is 119, this means that all bases where this article appears are counted. The time used for the search was 1990 to 2011.

Section 2 of the work presents the analysis relating to research data.

Portfolio building

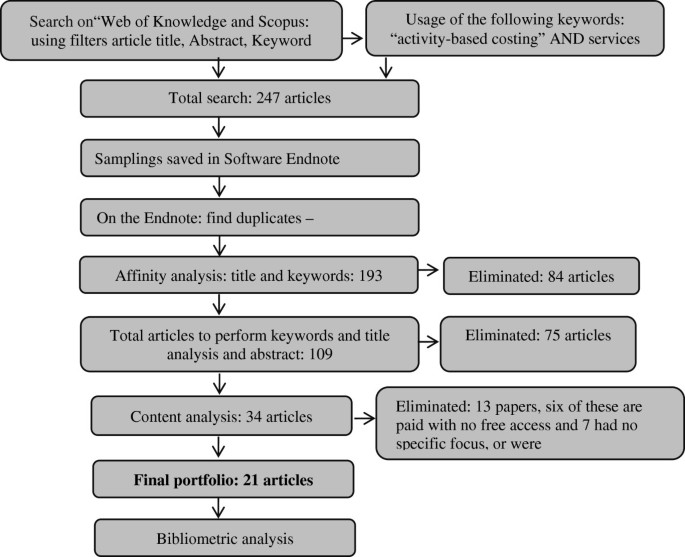

The phase selection of gross articles stock was completed with 247 articles found (Figure 2 ), according to the search criteria provided.

Results of the steps of building an article portfolio. Source: Authors.

For the next step, article stock filtration was performed, then stored in the management software bibliographic references EndNote version Web . This second stage was divided into three separation stages as to: (i) title alignment (ii) scientific recognition (citation number) of the articles and abstracts reading and, (iii) complete reading of the articles. Figure 2 shows a summary of the steps.

The review stage was performed with 34 articles, with proven scientific recognition, from these: 13 were eliminated (six bases were paid without access via portal Capes, and 7 had no specific focus of ABC method of costs in services, because they addressed only services or only ABC). At the end, there were 21 remaining articles, which build the portfolio on the topic in question (Table 1 ).

In the next subsection, the results of the portfolio profile will be presented, constructed as: recognition of scientific articles, journals that most stand out; featured authors and keywords used.

Bibliographic portfolio of articles analysis

Performed the entire procedure to build a representative bibliographic portfolio to discuss the use of the ABC method in services, the next step was to treat these articles through bibliometric analysis.

Bibliometrics (Dorban and Vandevenne, 1992 ; Macias-Chapula, 1998 ; Mukherjee, 2009 ; Tasca et al., 2010 ) is a technique that allows situating the research through various indicators and relationships. As the indicators can be used, the number of citations, co-authorship, number of patents, as well as maps can be made of scientific fields and countries. Table 2 shows the scientific recognition indicator held in the article portfolio.

Table 3 shows the indicator journals titles (Hassini et al., 2012 ) presents in articles of the bibliographic portfolio.

In Table 3 , one can find that the journals are of different areas, i.e., the ABC method of cost is applied to different types of services, whether health, libraries, transportation, security, financial institutions, logistics and others.

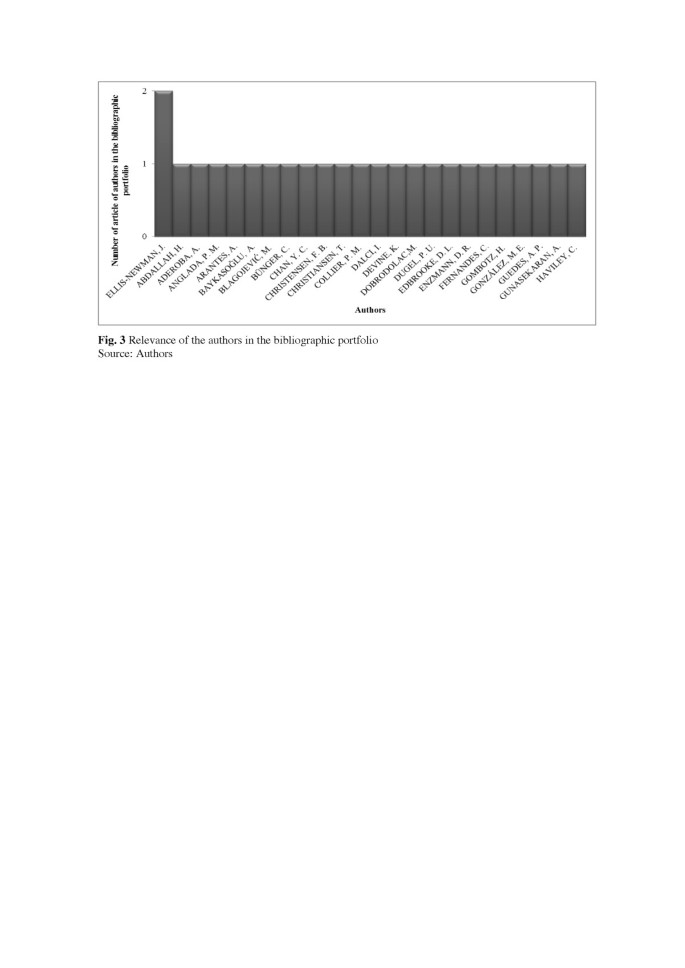

Another indicator used was the number of articles per author in the portfolio, as shown in Figure 3 . Altogether 59 authors were identified in the portfolio; none of the authors had a higher participation. The only author with two articles in the portfolio was Ellis-Newman, J.

Relevance of the authors in the bibliographic portfolio. Source: Authors.

The keywords index found in the portfolio was also analyzed. The highlight is the keyword activity-based costing the search root word, followed by health services, economics, hotels. This may imply that the ABC method is used in service organizations with the intention of reducing costs and improving productivity. For articles on health, there is a reservation: they focus their application of the ABC method in restricted areas or department of a health organization.

Bibliometric analysis of the portfolio references

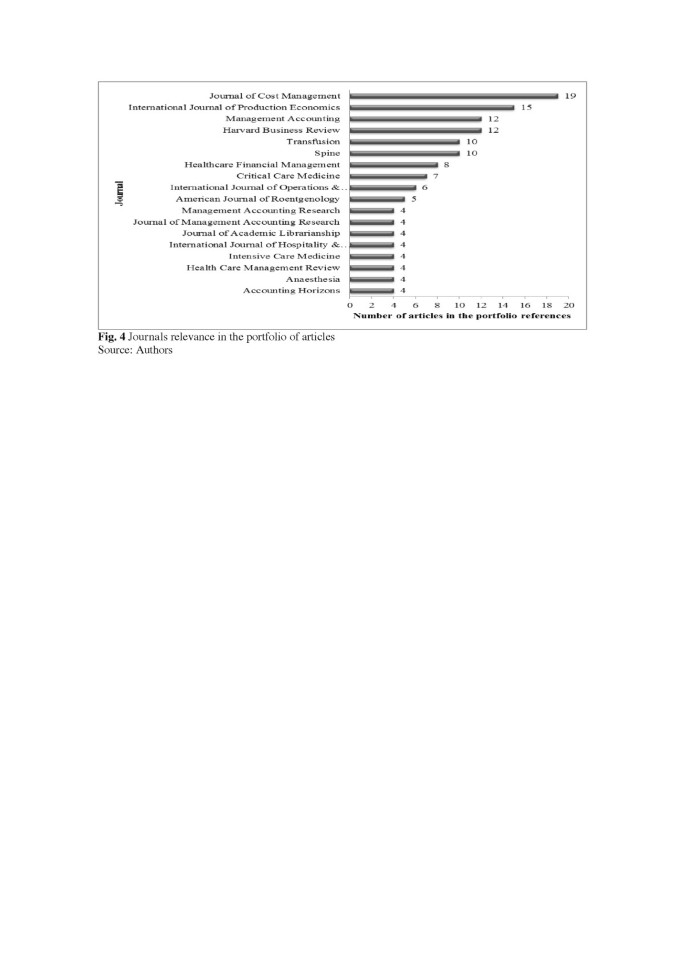

This subsection deals with the bibliometric analysis of the articles portfolio references. In total 305 references from 21 articles were recorded, pointing out that this result considers, only journal articles. It was found that 149 titles of journals or scientific journals were cited. Regarding the most relevant journals in the portfolio references, Journal of Cost Management and International Journal of Production Economics. Figure 4 illustrates the journals that had four or more articles in the portfolio reference.

J ournals relevance in the portfolio of articles. Source: Authors.

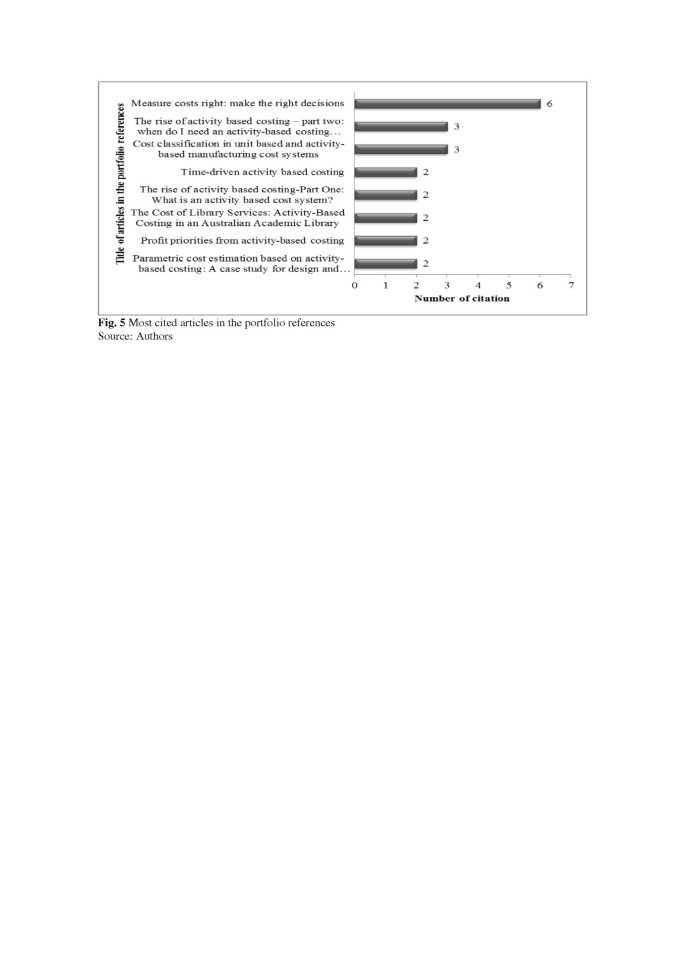

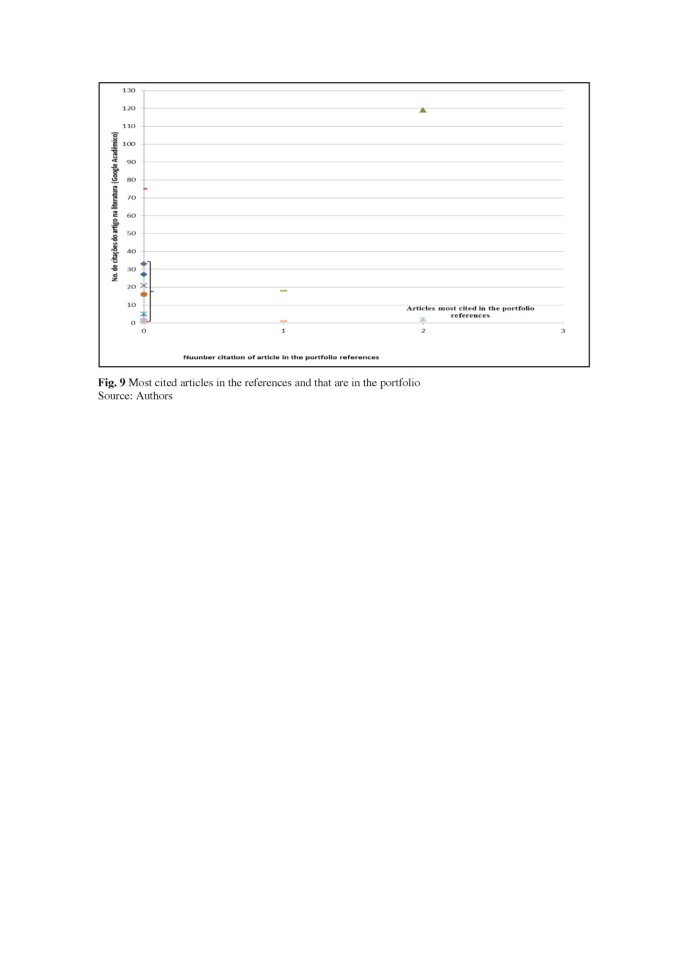

The next indicator analyzed was the most cited articles (Figure 5 ) in the portfolio references, for such the number of times it was cited was counted.

Most cited articles in the portfolio references. Source: Authors.

By means of Figure 5 , it can be seen that the most cited article in the portfolio references was: Measure costs right: make the right decisions written by Robin Cooper and Robert S. Kaplan published in Harvard Business Review in 1988. And with three citations, the articles by Robin Cooper are shown: The rise of activity based costing – part two: when do I need an activity-based costing system published in the Journal of Cost Management in 1988 and, Cost classification in unit-based and activity-based manufacturing cost systems, also published in the Journal of cost Management in 1990.

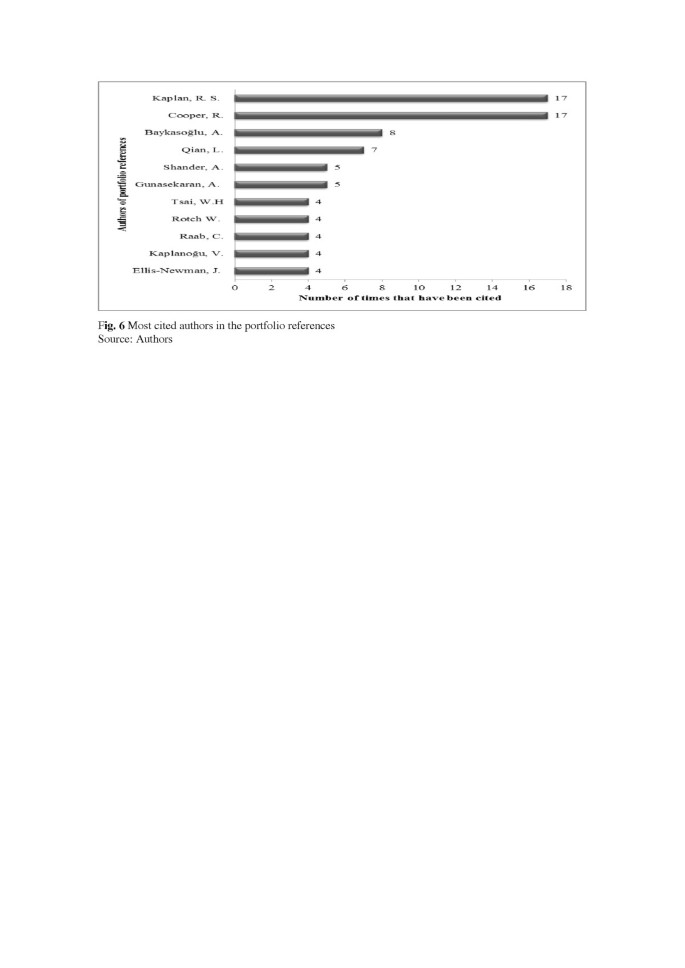

Finally, the most cited author was investigated in the portfolio references. The highlighted authors are shown in Figure 6 .

Most cited authors in the portfolio references. Source: Authors.

So this section held bibliometric analysis of the articles portfolio references built on the application of the ABC method of costs in service.

Analysis: portfolio versus portfolio references

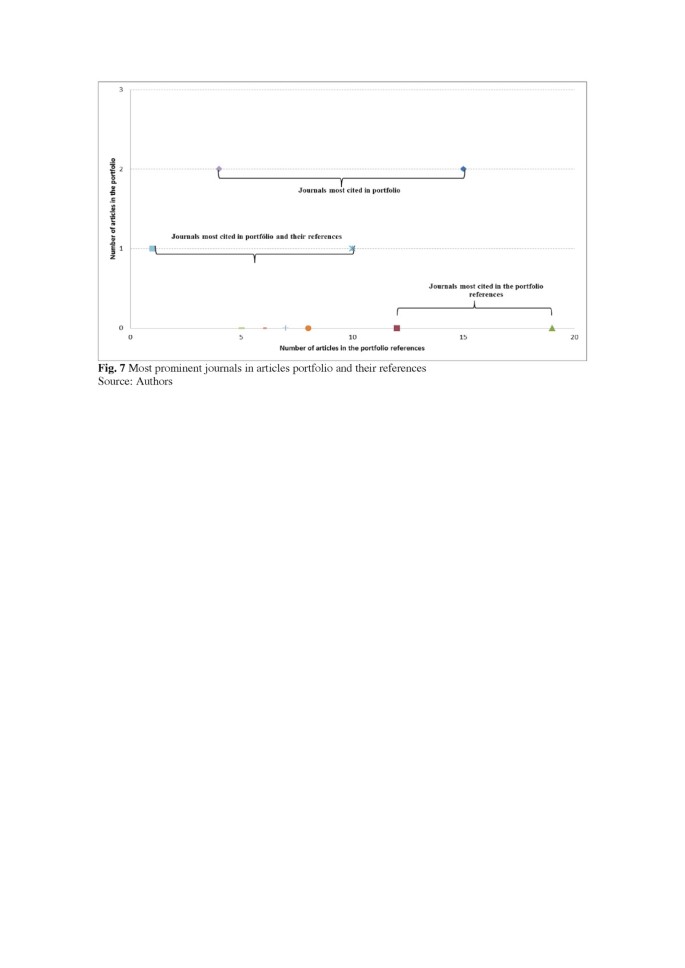

Having the portfolio built with 21 representative articles on the subject using the ABC method in services, it was identified: the most prominent journals, titles of highlighted articles; authors who have excelled. Figure 7 shows the most prominent journals in portfolio and in its references.

Most prominent journals in articles portfolio and their references. Source: Authors.

The most cited article in the portfolio references was the Journal of Cost Management (cited 19 times in portfolio references), but no article was accounted for in the portfolio itself with this journal. This might be due to the fact that the research topic is very specific in application in services and thus causing many articles, for example, applied in industry have been left out. The second prominent journal in the portfolio as well as in its references was the International Journal of Production Economics (cited 15 times in references, and two in the portfolio). Another prominent journal in the portfolio was Journal of Academic Librarianship presenting two citations in the portfolio and only four in its references.

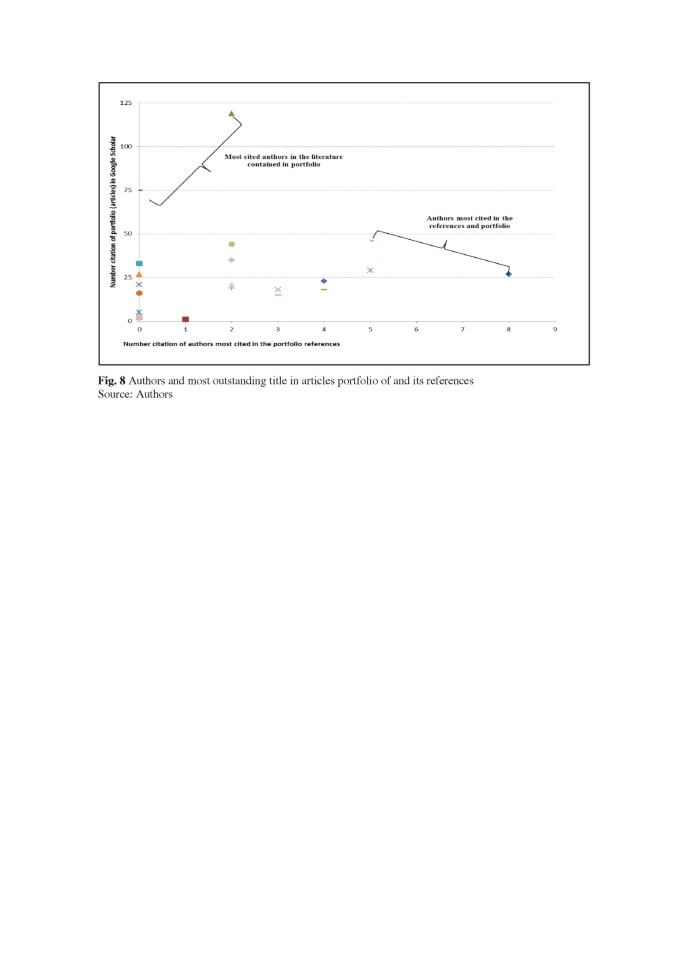

The following analysis refers to the authors featured in the portfolio and its references (Figure 8 ). The most cited author in the literature is Chan, Yee-Ching Lilian with article Improving hospital cost accounting with activity-based costing, published in Health Care Management Review in 1993. This article was checked in Google Scholar and had 119 citations on 13/03/2012, and this number tends to increase every day that it is checked due the fact, that this or any other article is being cited in research and studies. References in the article portfolio have been cited 2 times. The second most cited paper in the literature (75 citations in Google Scholar and not once in the portfolio references) and present the articles portfolio is A new method of accurately Identifying costs of individual Patients in intensive care: the initial results of Edbrooke, D. L.; Stevens, V. G., Hibbert, C. L., published in Intensive Care Medicine in 1997.

Authors and most outstanding title in articles portfolio of and its references. Source: Authors.

Also in Figure 8 , the most cited authors in the references were Baykasoǧlu, A. and Gunasekaran, A., with 8 and 5 citations respectively. It is important to note that the citations of these authors do not relate to those contained in the portfolio, but to other works by them. The next and final analysis relates to the most outstanding items in the portfolio and its references, as shown in Figure 9 . The articles present in the portfolio and the most cited in the references are: Improving hospital cost accounting with activity-based costing (Chan, Yee-Ching Lilian); Logistic costs case study - an ABC approach (Themido, I., Arantes, A., Fernandes C., Guedes, A.P.); and Application of activity-based costing (ABC) is a Peruvian NGO healthcare provider (Waters, H., Abdallah, H.; Santillán, D.), each with two citations.

Most cited articles in the references and that are in the portfolio. Source: Authors.

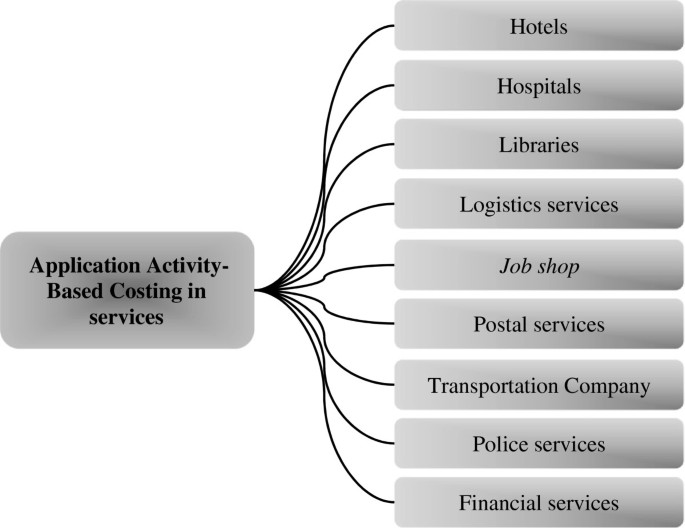

Therefore, with this research it was possible to the researcher knowledge needed to start a study on the subject application of the ABC method in services and also classify the types of services where they were applied (Figure 10 ).

Application of the ABC method in different types of service found in the bibliographic portfolio. Source: Authors.

In general, the characteristics of the built portfolio were:

The majority (8 articles) of the applications of the ABC method is in organizations that provide health services.

The ABC method is used in its traditional or adapted form, sometimes it is integrated into some kind of tool such as QFD and AHP.

Most of these researches use the method to identify activities that add value and those that cause injury, in order to improve their productivity and competitiveness.

Therefore, using the ABC method of cost requires a detailed study of organizations so that they can conduct an analysis to identify activities which consume resources. An organization wishing to implement the ABC method should provide sufficient resources, but also those involved in the project should carefully observe which the cost drivers are to be used. If the organization does not provide the necessary resources, the results are disastrous.

Conclusions

Organizations have a constant need to be prepared to continue competing, which shows the search for alternatives for their stay in the market. It has become a common goal in today's business environment, to improve efficiency and restructure organization, turning it effective. In this context, information about costs has become increasingly important to support and justify the process of decision-making. For the implementation of ABC to be successful, top management commitment will be needed, so that all objectives are in accordance with: strategy, quality and performance assessment, awareness of time that is required for this implementation and experience in media.

This article aims to build an article portfolio about the application of the ABC method in services to contribute to research on this subject. For this purpose, a three-stage procedure was performed, Planning, Implementation and Synthesis for the preparation of this portfolio. Searches carried form via journal portal Capes (in the databases ISI Web of Knowledge and Scopus ), comprising the period 1990–2011.

The formation of the bibliographic portfolio on the ABC method in service firms resulted in the identification of 21 articles presented in Frame 1. A bibliometric analysis of the portfolio and its references was subsequently held. Finally a general analysis of what is each of these articles. And, by analyzing the content of each article it was possible to classify in what types of service they were applied. The majority (8 articles) of the applications of the ABC method is in organizations that provide health services.

Some limitations in the research can be highlighted: (i) only articles published in international journals were considered, (ii) research sources such as books, dissertations, theses, proceedings of conferences, events were excluded, (iii) the time period considered for the search was 1990–2011, (iv) only two databases were considered, and (v) only databases freely accessible via the portal Capes were considered. This work, besides contributes to fostering discussions in academic science, also contributes to the business environment. For the survival of small organizations depends on their ability to generate profits. However, the generation of profits does not occur randomly, it requires careful planning, several management analyzes for decision-making.

Therefore, it is important to note that a well-structured costing method according to the needs of the organization supports consistent decision-making and is an efficient management tool. An organized cost analyzes and control system, appropriate to the aims of the organization, outlines what is happening, how best to allocate resources and therefore optimize the results.

Aderoba A: A generalised cost-estimation model for job shops. Int J Prod Econ 1997, 53(3):257-263. 10.1016/S0925-5273(97)00120-5

Article Google Scholar

Anderson SW: Managing costs and cost structure throughout the value chain: research on strategic cost management. Working paper, University of Melbourne, Department of Accounting and Business Information Systems, Forthcoming in: Chapman, C, Hopwood, A, Shields, M. Handbook of Management Accounting Research, v. 2 . Oxford: Elsevier; 2005.

Google Scholar

Baykasoǧ lu A, Kaplanoǧ lu V: Application of activity-based costing to a land transportation company: a case study. Int J Prod Econ 2008, 116(2):308-324. 10.1016/j.ijpe.2008.08.049

Blagojević M, Marković D, Kujačić M, Dobrodolac M: Applying activity based costing model on cost accounting of provider of universal postal services in developing countries. Afr J Bus Manag 2010, 4(8):1605-1613.

Bortoluzzi SC, Ensslin SR, Ensslin L, Valmorbida SMI: Avaliação de desempenho em redes de pequenas e médias empresas: estado da arte para as delimitações postas pelo pesquisador. Revista Eletrônica Estratégia & Negócios, Florianópolis 2011, 4(2):202-222.

Büyüközkan G, Çifçi G: A combined fuzzy AHP and fuzzy TOPSIS based strategic analysis of electronic service quality in healthcare industry. Expert Syst Appl 2012, 39(8):2341-2354.

Büyüközkan G, Çifçi G, Güleryüz S: Strategic analysis of healthcare service quality using fuzzy AHP methodology. Expert Syst Appl 2011, 38(8):9407-9424. 10.1016/j.eswa.2011.01.103

Calabrese A: Service productivity and service quality: a necessary trade-off? Int J Prod Econ 2012, 135(2):800-812. 10.1016/j.ijpe.2011.10.014

Chan YC: Improving hospital cost accounting with activity-based costing. Health Care Manage Rev 1993, 18(1):71-77.

Collier PM: Costing police services: the politicization of accounting. Crit Perspect Account 2006, 17(1):57-86. 10.1016/j.cpa.2004.02.008

Cotton WDJ, Jackman SM, Brown RA: Note on a New Zealand replication of the Innes et al. UK activity-based costing survey. Manage Account Res 2003, 14(1):67-72. 10.1016/S1044-5005(02)00057-4

Crossan MM, Apaydin M: A multi-dimensional framework of organizational innovation: a systematic review of the literature. J Manage Stud 2010, 47(6):1154-1191. 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00880.x

Dalci I, Tanis V, Kosan L: Customer profitability analysis with time-driven activity-based costing: a case study in a hotel. Int J Contemp Hospitality Manage 2010, 22(5):609-637. 10.1108/09596111011053774

Devine K, O'clock P, Lyons D: Health-care financial management in a changing environment. J BuS Res 2000, 48(3):183-191. 10.1016/S0148-2963(98)00083-6

Dorban M, Vandevenne AF: Bibliometric analysis of bibliographic behaviours in economic sciences. Scientometrics 1992, 25(1):149-165. 10.1007/BF02016852

Dugel PU, Bianchini K: Development of an activity-based costing model to evaluate physician office practice profitability. Ophthalmology 2011, 118(1):203-231. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.04.035

Duh R-R, Lin TW, Wang W-Y, Huang C-H: The design and implementation of activity-based costing: a case study of a Taiwanese textile company. Int J Account Inf Manage 2009, 17(1):27-52.

Edbrooke DL, Stevens VG, Hibbert CL: A new method of accurately identifying costs of individual patients in intensive care: the initial results. Intensive Care Med 1997, 23(6):645-650. 10.1007/s001340050388

Ellis-Newman J: Activity-based costing in user services of an academic library. Libr Trends 2003, 51(3):333-348.

Ellis-Newman J, Robinson P: The cost of library services: activity-based costing in an Australian academic library. J Acad Librarianship 1998, 24(5):373-379. 10.1016/S0099-1333(98)90074-X

Ensslin L, Ensslin SR, Lacerda RT, Tasca JE: ProKnow-C, Knowledge Development Process – Constructivist . Brasil: Processo Técnico com patente de registro pendente junto ao INPI; 2010.

Enzmann DR, Anglada PM, Haviley C, Venta LA: Providingprofessional mammography services: financial analysis. Radiology 2001, 219(2):467-473.

Førsund FR, Sarafoglou N: The tale of two research communities: the diffusion of research on productive efficiency. Int J Prod Econ 2005, 98(1):17-40. 10.1016/j.ijpe.2004.09.007

González ME, Quesada G, Mack R, Urritia I: Building an activity-based costing hospital model using quality function deployment and benchmarking. Benchmarking 2005, 12(4):310-329. 10.1108/14635770510609006

Grissemann US, Stokburger-Sauer NE: Customer co-creation of travel services: the role of company support and customer satisfaction with the co-creation performance. Tour Manage 2012, 33(6):1483-1492. 10.1016/j.tourman.2012.02.002

Gumpenberger C, Wieland M, Gorraiz J: Bibliometric practices and activities at the University of Vienna. Libr Management 2012, 33(3):174-183. 10.1108/01435121211217199

Gunasekaran A, Marri HB, Grieve JR: Justification and implementation of activity based costing in small and medium-sized enterprises. Logistics Inf Manage 1999, 12(5):386-394. 10.1108/09576059910295869

Gunasekaran A, Sarhadi M: Implementation of activity-based costing in manufacturing. Int J Prod Econ 1998, 56–57: 231-242.

Gunasekaran A, Spalanzani A: Sustainability of manufacturing and services: Investigations for research and applications. Int J Prod Econ 2012. In Press, Corrected Proof, Available online 19 May 2011

Hassini E, Surti C, Searcy C: A literature review and a case study of sustainable supply chains with a focus on metrics. Int J Prod Econ 2012. In Press, Corrected Proof, Available online 8 February 2012

Hussain M, Guanasekaran A: Activity-based cost management in financial services industry. Manag Service Qual 2001, 11(3):213-223. 10.1108/09604520110391324

Hussain MM, Gunasekaran A, Laitinen EK: Management accounting systems in Finnish service firms. Technovation 1998, 18(1):57-67. 10.1016/S0166-4972(97)00062-X

Innes J, Falconer M: The application of activity-based costing in the United Kingdom’s largest financial institutions. Serv Ind J 1997, 17(1):190-203. 10.1080/02642069700000010

Jänkälä S, Silvola H: Lagging effects of the use of activity-based costing on the financial performance of small firms. J Small Bus Manage 2012, 50(3):498-523. 10.1111/j.1540-627X.2012.00364.x

Kallunki JP, Silvola H: The effect of organizational life cycle stage on the use of activity-based costing. Manage Account Res 2008, 19(1):62-79. 10.1016/j.mar.2007.08.002

Kellermanns FW, Islam M: US and German activity-based costing: a critical comparison and system acceptability propositions. Benchmarking An Int J 2004, 11(1):31-51. 10.1108/14635770410520294

Lins LS, Silva RNS: Gestão empresarial com ênfase em custos: uma abordagem prática . São Paulo: Pioneira Thomson Learning; 2005.

Lutilsky ID, Dragija M: Activity based costing as a means to full costing: possibilities and constraints for European universities. Manage (Croatia) 2012, 17(1):33-57.

Macias-Chapula CA: O papel da informetria e da cienciometria e sua perspectiva nacional e internacional. Ciência da Informação 1998, 27(2):134-140.

Mukherjee B: Scholarly research in LIS open access electronic journals: a bibliometric study. Scientometrics 2009, 80(1):169-196.

Narayanan VG, Sarkar RG: The impact of activity-based costing on managerial decisions at Insteel Industries: a field study. J Econ Manage Strat 2002, 11(2):257-288. 10.1162/105864002317474567

Niraj R, Gupta M, Narasimhan C: Customer profitability in a supply chain. J Marketing 2001, 65(3):1-16. 10.1509/jmkg.65.3.1.18332

Pernot E, Roodhooft F, Van Den Abbeele A: Time-driven activity-based costing for inter-library services: a case study in a university. J Acad Libr 2007, 33(5):551-560. Sep 10.1016/j.acalib.2007.06.001

Richardson RJ: Pesquisa social: métodos e técnicas . 3rd edition. São Paulo: Atlas; 2008.

Salem-Mhamdia ABH, Ghadhab BB: Value management and activity based costing model in the Tunisian restaurant. Int J Contemp Hospitality Manage 2012, 24(2):269-288. 10.1108/09596111211206178

Schulze M, Seuring S, Ewering C: Applying activity-based costing in a supply chain environment. Int J Prod Econ 2012, 135: 716-725. 10.1016/j.ijpe.2011.10.005

Shander A, Hofmann A, Ozawa S, Theusinger OM, Gombotz H, Spahn DR: Activity-based costs of blood transfusions in surgical patients at four hospitals. Transfusion 2010, 50(4):753-765. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02518.x

Soegaard R, Christensen FB, Christiansen T, Bünger C: Costs and effects in lumbar spinal fusion. A follow-up study in 136 consecutive patients with chronic low back pain. Eur Spine J 2007, 16(5):657-668. 10.1007/s00586-006-0179-8

Stefano NM: Gerenciamento de custos em pequenas empresas prestadoras de serviço utilizando o Activity Based Costing (ABC). Estudios Gerenciales 2011, 27(121):13-35.

Stefano NM, Godoy LP, Casarotto Filho N, Santa CA: Uma proposta de gerenciamento de custos em pequenas organizações de serviço utilizando o Activity Based Costing. Revista ABCustos 2010, 5(2):01-28.

Susskind AM: Guest service management and processes in restaurants: what we have learned in fifty years. Cornell Hosp Q 2010, 51(4):479-482. 10.1177/1938965510375028

Tan KC, Goudarzlou A, Chakrabarty A: A bibliometric analysis of service research from Asia. Manag Service Qual 2010, 20(1):89-101. 10.1108/09604521011011649

Tasca JE, Ensslin L, Ensslin SR, Alves MBM: An approach for selecting a theoretical framework for the evaluation of training programs. J Eur Ind Train 2010, 34(7):631-655. 10.1108/03090591011070761

Themido I, Arantes A, Fernandes C, Guedes AP: Logistic costs case study - an ABC approach. J Oper Res Soc 2000, 51(10):1148-1157.

TSAI H-H: Research trends analysis by comparing data mining and customer relationship management through bibliometric methodology. Scientometrics 2011, 87: 425-450. 10.1007/s11192-011-0353-6

Tsay M-y, Zhu-yee S: Journal bibliometric analysis: a case study on the Journal of Documentation. J Doc 2011, 67(5):806-822. 10.1108/00220411111164682

Van Raan AFJ: Properties of journal impact in relation to bibliometric research group performance indicators. Scientometrics 2012, 92(2):457-469. 10.1007/s11192-012-0747-0

Vazakidis A, Karagiannis I: Activity-based management and traditional costing in tourist enterprises (a hotel implementation model). Oper Res 2011, 11(2):123-147.

Waters H, Abdallah H, Santillán D: Application of activity-based costing (ABC) for a Peruvian NGO healthcare provider. Int J Health Plann Manage 2001, 16(1):3-18. 10.1002/hpm.606

Download references

Acknowledgement

We thank: CNPq - National Council for Scientific and Technological Development and Program in Production Engineering, Federal University of Santa Catarina, Brazil.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Program in Production Engineering, Federal University of Santa Catarina,, Florianopolis, Santa Catarina, Brazil

Nara Medianeira Stefano & Nelson Casarotto Filho

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Nara Medianeira Stefano .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

The authors participated in the preparation of the manuscript, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Authors’ original file for figure 1

Authors’ original file for figure 2, authors’ original file for figure 3, authors’ original file for figure 4, authors’ original file for figure 5, authors’ original file for figure 6, authors’ original file for figure 7, authors’ original file for figure 8, authors’ original file for figure 9, authors’ original file for figure 10, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Stefano, N.M., Filho, N.C. Activity-based costing in services: literature bibliometric review. SpringerPlus 2 , 80 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-2-80

Download citation

Received : 23 October 2012

Accepted : 31 January 2013

Published : 05 March 2013

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-2-80

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Bibliometrics

- Bibliography portfolio

A longitudinal literature review of life cycle costing applied to urban agriculture

- ENVIRONMENTAL LCC

- Open access

- Published: 02 June 2020

- Volume 25 , pages 1418–1435, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Alexandra Peña ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6774-5718 1 &

- M. Rosa Rovira-Val 1 , 2

4537 Accesses

18 Citations

Explore all metrics

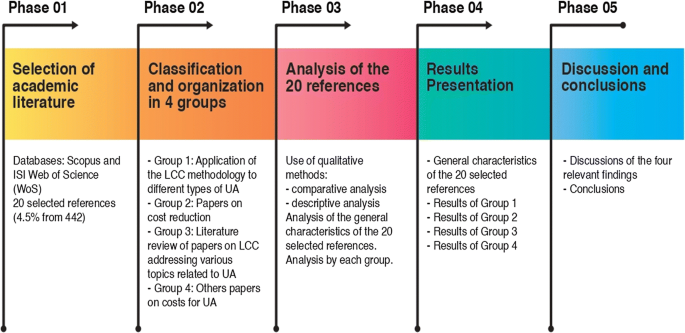

The aim of this research is to carry out a literature review of the use of life cycle costing (LCC) in the urban agriculture (UA) sector by analysing its evolution over a 22-year period from its beginning in 1996 to July 2018.

A total of 442 references were obtained from two principal databases, Scopus and Web of Science (WoS). After a long refining process, 20 (4.5%) references containing the keywords LCC and UA were selected for analysis. Then, we classified and organized the selected references in 4 groups. Qualitative methods were used for analysis, and results on general characteristics of the 20 references and by each group were elaborated. Lastly, we discussed and concluded the most significant findings. Limitations and future research were also included.

Results and discussion

Our major findings were as follows: (i) urban horticulture was the most studied urban agriculture practice among studies that used LCC for UA; (ii) LCC plays a secondary role in its integration with LCA; (iii) only 4 of the10 papers in group 1 used additional financial tools; (iv) very few (3) papers appropriately applied the four main LCC stages; and on the other side, essential costs like infrastructure, labour, maintenance, and end-of-life were frequently not included.

Conclusions

Since we found that life cycle assessment (LCA) was the predominant methodology, we suggest that future research apply both LCA and LCC analyses at the same level. The LCC analysis was quite incomplete in terms of the costs included in each LCC stage. We recommend that the costs at the initial or construction stage be considered a necessity in future studies in order to implement these new systems on a large scale. Due to the limited use of labour cost at the operation stage, we also suggest that labour be included as an essential part of the urban production process. Finally, for more complete LCC analysis for UA, we recommend (i) that all LCC stages be considered and (ii) that additional financial tools, such as net present value (NPV), internal rate of return (IRR) and payback period (PBP), be used to complement the LCC analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Review: life cycle assessments in nigeria, ghana, and ivory coast, current trends and limitations of life cycle assessment applied to the urban scale: critical analysis and review of selected literature.

Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment: What Is It and What Are Its Challenges?

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Nowadays, more than half of the world’s population lives in urban areas, and this tendency is expected to increase to 68% by 2050 (UN DESA 2018 ). For example, in the European Union alone, 75% of the population lives in cities, and this number is estimated to reach 80% by 2020.

As a result, rapid urbanization can bring an extensive range of undesirable consequences, such as a reduction in fertile lands, deforestation, water and air pollution, reduced drainage of rainfall, poverty and problems in the supply of fresh food (Baud 2000 ). In this sense, some experts are concerned about the capacity of the biosphere to provide enough food for the increased human population in urban areas (Gilland 2006 ).

To find a solution to cities’ fresh food problems, Nadal et al. ( 2015 ) suggested that new forms of agriculture should be found to guarantee food security for the population at a lower cost within the framework of sustainable development. Urban agriculture (UA) would be a good example of this.

In the literature, there are many definitions of UA, but in general, it can be defined as “an industry located within (intra-urban) or on the fringe (peri-urban) of a town, city or metropolis, which grows or raises, processes and distributes a diversity of food and non-food products…” (Mougeot, 2000 , p.11). UA is a broad term and includes not only plant cultivation and animal rearing but also other related activities such as the production and selling of agricultural inputs, post-harvesting, marketing and commercialization.

According to many authors, UA, which provides fresh food in urban settlements, may alleviate cities’ food problems and simultaneously contribute to their sustainability (Sanyé-Mengual et al. 2017 ; Specht et al. 2014 ; Benis and Ferrão 2018 ; Ackerman et al. 2014 ; Goldstein et al. 2016 ; Opitz et al. 2016 ). In this regard, various authors found a strong relationship between UA and the three pillars of sustainability: environment, economy and society.

To assess the different levels of sustainability of UA, the use of an appropriate methodology is needed. Pieces of evidence from the scientific literature show that life cycle sustainability assessment (LCSA) is the main methodology used for this purpose in many studies (Sanyé-Mengual et al. 2015a ; Liaros et al. 2016 ; Sanyé-Mengual et al. 2018 ; Kim and Zhang, 2018 ; Dorr et al. 2017 ; Benis et al. 2018 ). Three distinct analyses are available in the framework of LCSA: life cycle assessment (E-LCA or LCA), which is used for the evaluation of environmental aspects; life cycle costing (LCC), which is used for the evaluation of economic aspects and social life cycle assessment (S-LCA), which is used for the evaluation of the social aspects of sustainability (Kloepffer 2008 ; Swarr et al. 2011 ).

As far as we know, most UA studies focus mainly on the environmental aspects of UA by using LCA. In this sense, LCA is the most widely used life cycle methodology based on its implementation and the interpretation of its results (Orsini et al. 2014 ; Goldstein et al. 2016 ; Sanjuan-Delmás et al. 2018 ). While the environmental aspects of UA are extensively studied in the literature, an evaluation of the economic aspects of UA through LCC is still missing (Sanyé-Mengual et al. 2017 ). Some authors have used combined LCA and LCC analyses, but the results are not relevant because LCA and LCC can be correlated negatively and positively; i.e. financial feasibility does not always mean environmental viability and vice versa (European Commission 2010 ).

The aim of LCC is to quantify the total cost over the life cycle of a project to identify the cost-effectiveness of alternative projects for input into a decision-making or evaluation process (Norris 2001 ; ISO 2008 ). LCC, also known as life cycle cost analysis (LCCA), is an economic evaluation technique that takes into consideration all costs and cash flows that appear during the life cycle of a project, product or service (Ammar et al.2013) from the costs of design and acquisition through to operation, maintenance and disposal (Wu and Longhurst 2011 ; ISO 2008 ).

There are other popular methods for assessing the economic performance of a project or product, such as the cost-benefit analysis (CBA) (Carter and Keeler 2008 ; Sanyé-Mengual et al. 2015a ; Benis et al. 2018 ) and whole life costing (WLC) (ISO 2008 ). The characteristics and procedures of CBA and WLC however are very similar to those of LCC and most of the time that authors refer to their methods as CBA or WLC while the methodology that they have used is LCC.

This methodology became popular in the mid-1960s, but 1996 is considered the starting point because in this year, the first official document describing the theoretical framework for LCC, the handbook entitled Life Cycle Costing Manual for the US Federal Management Program (Fuller and Petersen, 1996 ), was published. Currently, LCC is spread worldwide and is one of the most commonly used procedures for economic assessment in different industries. Evidence from the scientific literature shows the growing interest in this methodology in industry, infrastructure, construction and building sectors (Naves et al. 2018 ).

As far as we know, there is no evidence of a literature review on LCC applied to UA because the only LCC review papers that we found were for the aforementioned sectors. The purpose of this paper is fill this gap by studying the evolution of LCC analysis in a UA context from 1996 to July 2018 by conducting a literature review.

This study is the first attempt to systematize the existing academic literature on the use of LCC for the growing UA sector. The results will be helpful in identifiying common problems in LCC calculation, analysis and interpretation. The findings will also serve as a guide for future researchers by promoting a greater application of LCC in the UA sector.

We have organized the paper as follows:

Part 1: Introduction,

Part 2: Methods,

Part 3: Results,

Part 4: Discussion, and

Part 5: Conclusions.

This study is a longitudinal analysis of a 22-year period, from 1996 to July 2018. The year 1996 is the starting point of our investigation because it is the year of the publication of the first official paper containing a theoretical framework for LCC (Fuller and Petersen, 1996 ).

Figure 1 shows the methodology used for this research including five phases which we explain below.

Research methodology process

The first phase was to select the academic papers for our review. Therefore, we had to find the most appropriate keywords to successfully describe the relationship between LCC and UA. For LCC, we chose the 4 most popular words: LCC, life cycle cost, life cycle costing and life cycle cost analysis. As for UA, we found a greater number of different terms, but the most popular were urban agriculture (Orsini et al. 2013 ; Goldstein et al. 2016 ; Sanyé-Mengual et al. 2017 ; Hamilton et al. 2014 ; Specht et al. 2014 ); urban gardening/gardens (Orsini et al. 2013 ; Grewal and Grewal 2012 ); urban farming/farms (Orsini et al. 2013 ; Specht et al. 2014 ) and rooftop greenhouse/garden/farms (Cerón-Palma et al. 2012 ; Orsini et al.2014; Sanyé-Mengual et al. 2015b ; Sanyé-Mengual et al. 2015c ; Dorr et al. 2017 ; Sanyé-Mengual et al. 2017 ; Zinia and McShane 2018 ; Artmann and Sartison, 2018 ). To organize our database, we classified all the different words and terms regarding UA into five groups (see Table 1 ). After that, we created different combinations of the keywords for both LCC and UA.

Scopus and ISI Web of Science (WoS) online databases were selected because they are the most widespread and are used by several authors in the field (Petit-Boix et al. 2017 ; Ilg et al. 2017 ; Kambanou and Lindahl 2016 ; Scope et al. 2016 ). As a result, we obtained 442 references, 223 were from WoS and 219 from Scopus, which then had to be refined. Given that the abbreviation LCC can be linked to other expressions and concepts, we had to remove the results which were not associated with LCC. Moreover, the focus of our research was on UA only; therefore, we also excluded papers on conventional agriculture from the analysis. Consequently, the remaining references included both LCC and UA. Finally, we removed all the repeated references. The final result was 20 references for analysis (4.5% of the initial 442) containing both terms LCC and UA.

Then, the second phase was to classify the selected references into 4 groups. The underlying criteria for classification were similarity of the topic and type of the study (empirical or literature review).

Group 1: Application of the LCC methodology to different types of UA consisted of 10 papers describing the use of LCC methodology in different types of UA, e.g. home gardens, rooftop greenhouses and aquaponics systems. In Group 2: Papers on cost reduction were made up of 3 papers on cost reduction. Group 3: Literature review of papers on life cycle costs addressing various topics related to UA included 4 literature reviews. Group 4: Other papers on costs for UA were composed of 3 research papers on costs of UA which did not specify the methodology used.

The third phase was to analyse both the characteristics of the set of 20 selected references as a whole and the distinctive aforementioned groups using qualitative methods (Saldaña 2003 ; Ragazzi 2017 ). We mainly used comparative analysis, but in some cases, a descriptive analysis was applied when it was not possible to compare.The next stage (phase 4) was to present the results on general characteristics of the 20 selected references and the results group by group.

The last step of the methodological process (phase 5) was to discuss and conclude the most relevant findings. Limitations and suggestions for future research were also presented.

In this section, we present the results on the general characteristics of the 20 references in terms of the number of publications by year, type of paper and source, leading regions and countries to show the evolution of the use of LCC for UA. After that, the results by groups are presented.

3.1 General characteristics

In this section, we present the general characteristics of the 20 papers selected.

We found that the first scientific paper on LCC applied to UA was published in 2008 (Nguyen and Weiss 2008 ) just after the publication of the first standard: ISO ( 2008 ) containing the theoretical basis of this methodology. Most of the papers (6 publications or 30%) were published in 2018, followed by 2015 (5 publications or 25%) and 2017, which had 3 publications or 15%. In 2014 and 2016, 2 papers were published for each year, while in 2008 and 2009, we only found one paper per year. During the next four years (2010-2011-2012-2013), we did not find any publication.

According to the results, the most important year was 2015 because of the substantial increase in the publications, e.g. from zero, one or two papers in the first seven years to 5 in 2015. In 2016, we noticed a small decrease, but over the next two years (2017 and 2018), the number of publications increased notably; e.g. in 2018, the growth was 15% compared with that of the previous year. From these results, we can conclude that the interest in using LCC for UA is increasing and that this tendency will probably continue in the coming years (Fig. 2 ).

Number of publications by year

Regarding the types of papers and their sources, we found that all the references were articles. Of the articles, 16 or 80% were original papers and 4 or 20% were review papers. Peer-reviewed journals were the main source, accounting for 85% of the total number of references, while the remaining 15% were conference proceedings (Fig. 3 ).

Type of source and type of paper

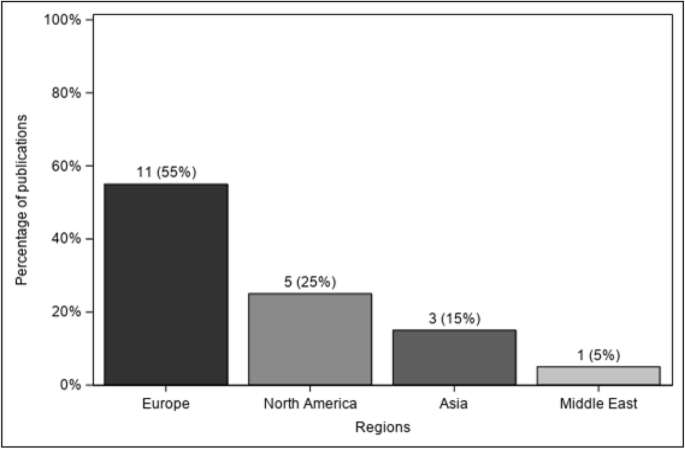

By regions, Europe was the leading region with 11 articles or 55% of the total, followed by North America (Canada and USA) with 5 publications or 25%. Asia had 3 papers (15%), while the Middle East (Israel) had only one (Fig. 4 ).

LCC for UA papers by regions

Within the European region, Spain with 4 publications and Italy with 2 had a preeminent position over the rest of the countries which had only 1 publication (Fig. 5 ).

LCC for UA papers by countries in the European region

3.2 Group 1: application of the LCC methodology to different types of UA

This first group included 10 papers (50% of total selected) describing the application of LCC to different types of UA, e.g. home gardens, rooftop greenhouses and aquaponics systems. We analysed the papers in relation to 10 different comparison criteria that we grouped into three parts: (i) type of urban agricultural practice, research topic; LCC integration with LCA or S-LCA and LCC guildelines followed; (ii) system boundaries, functional unit, use of financial tools and additional analyses for assessment; (iii) type of LCC (conventional, environmental and societal) and costs used according to the life cycle stage.

3.2.1 Type of urban agricultural practice, research topic, LCC integration with LCA/S-LCA and LCC guidelines followed

Table 2 presents a summary of the results by type of urban agricultural practice, research topic, LCC integration with LCA/S-LCA and LCC guidelines followed.

In the literature, there are several basic urban agricultural practices: horticulture, aquaculture, livestock raising, forestry and other farming activities (Baumgartner and Belevi 2001 ).

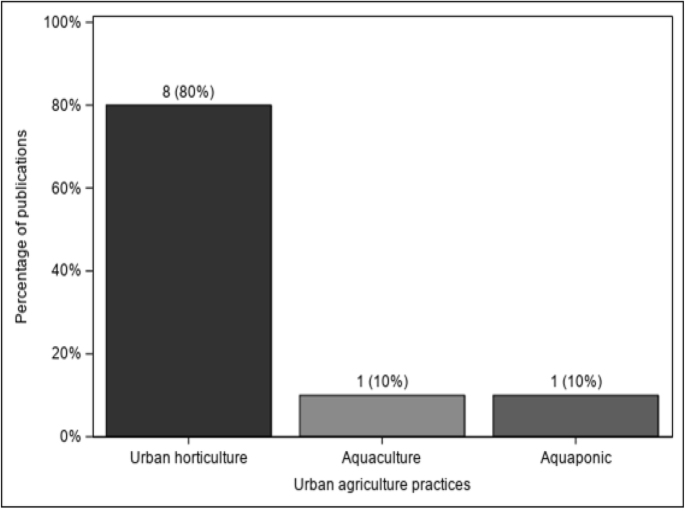

Urban horticulture related to the growth of vegetables or fruits was the most studied urban agricultural practice in 8 of the 10 papers in this group, while Kim and Zhang ( 2018 ) studied aquaculture (fish production), and Forchino et al. ( 2018 ) analysed an aquaponics system (fish and plants co-production). Figure 6 displays these findings graphically.

Type of urban agricultural practices

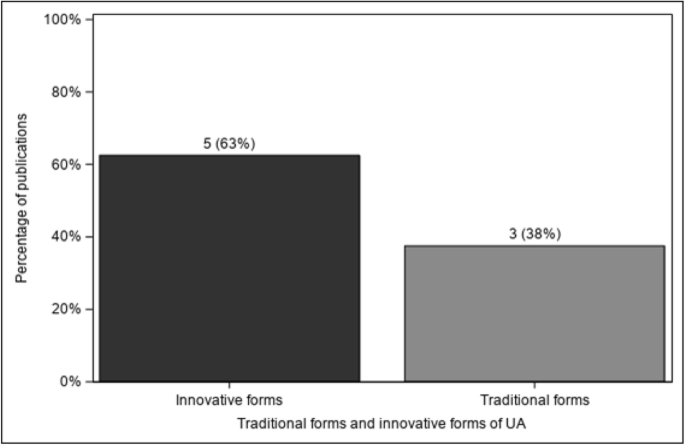

To better illustrate these results, we classified the urban horticulture papers into two subgroups. In the first subgroup, 3 papers on traditional forms of UA, such as home gardens (Opher et al. 2018 ; Sanyé-Mengual et al. 2018 ) and multi-channel greenhouses (Llorach-Massana et al. 2016 ), were included. The second subgroup comprised 5 papers on some innovative forms of UA, such as indoor farms (Liaros et al. 2016 ), rooftop greenhouses for open-air production (Benis et al. 2018 ), rooftop greenhouses (Sanyé-Mengual et al. 2015a ) and rooftop gardens (Dorr et al. 2017 ; Sanyé-Mengual et al. 2015c ). All of these innovative forms are part of the building-integrated forms of UA, such as vertical farming or ZFarming and urban rooftop agriculture (URA). We placed 5 of the urban horticulture papers in the second group, while the remaining 3 were included in the first group. Figure 7 shows the proportion between papers on traditional forms and innovative forms of UA.

Proportion between papers on the traditional forms and innovative forms of UA

From this, we can state that the focus of the authors using LCC for UA in the studied period of 22 years (1996–2018) was mainly on the building-integrated forms of UA (indoor farms, rooftop greenhouses, rooftop gardens) rather than on the traditional ones (home gardens and multi-channel greenhouses).

We found different research topics in the 10 papers of group 1.

From the 8 papers on urban horticulture practice, Liaros et al. ( 2016 ) evaluated the economic efficiency of urban indoor plant factories with artificial lighting as a business model, while Benis et al. ( 2018 ) compared two of the main uses of rooftops: urban food production and energy generation. Llorach-Massana et al. ( 2016 ) analysed the environmental and economic performance of the use of phase-change materials for a solar energy storage system used in a root zone to replace conventional root zone systems that depend on gas, oil or biomass. More specifically, they studied its application for improving the productivity of a multi-channel greenhouse. Opher et al. ( 2018 ) assessed the sustainability of four water reuse approaches for toilet flushing and garden irrigation in urban dwellings. The commonality among the 4 remaining papers was the analysis of the economic sustainability of urban food production (Sanyé-Mengual et al. 2018 ; Dorr et al. 2017 ; Sanyé-Mengual et al. 2015a , c ). Sanyé-Mengual et al. ( 2018 ) investigated the environmental impacts and the economic costs of vegetables produced in a home garden in Padua (Italy), while Dorr et al. ( 2017 ) assessed the environmental and economic impacts of rooftop gardening practices on crop and substrate selection. Sanyé-Mengual et al. ( 2015a ) estimated the environmental and economic performance of a rooftop greenhouse (RTG) in Barcelona in comparison with a multi-channel greenhouse in Almeria. Finally, Sanyé-Mengual et al. ( 2015c ) compared different cultivation techniques and crops. Regarding the papers on fish production, Kim and Zhang ( 2018 ) investigated solar water heaters for the improvement of fish production (aquaculture), whereas Forchino et al. ( 2018 ) quantified the environmental and economic impacts of the design of an indoor aquaponics system.

On the other hand, we noted that, of the 10 papers that formed the first group, only Liaros et al. ( 2016 ) and Benis et al. ( 2018 ) applied LCC in isolation from the other life cycle analyses. This means in general the authors preferred to combine the LCC analysis with LCA or S-LCA. The reason for this was perhaps that they wanted to illustrate the full picture of sustainability including the environment, economy and society. LCA and LCC analyses must be executed in the same way, e.g. the same system boundaries, functional units and allocation methods (Hunkeler et al. 2008 ). However, LCA and LCC can be correlated negatively or positively; i.e. financial feasibility does not mean environmental viability and vice versa (European Commission 2010 ).

With reference to the LCC guidelines followed, ISO ( 2008 ) was the most commonly used in 5 of the 10 papers (Dorr et al. 2017 ; Llorach-Massana et al. 2016 ; Sanyé-Mengual et al., 2015a and 2015c ; Sanyé-Mengual et al. 2018 ), and the updated version, ISO ( 2017 ), was found in the publication by Kim and Zhang ( 2018 ). Other LCC guidelines, such as those by Ciroth and Franze ( 2009 ), were applied in the study by Forchino et al. ( 2018 ), while Liaros et al. ( 2016 ) used the following paper for this purpose: Whole life costing in construction: a state of the art review (Kishk et al. 2003 ). Finally, only the guideline ISO ( 2006 ) was used for both LCA and LCC analyses in Sanyé-Mengual et al. ( 2018 ).

3.2.2 System boundaries, functional unit, financial tools and additional analyses for assessment

Table 3 shows a summary of the findings by system boundaries and functional unit.

We found three different approaches for assessment in relation to the system boundaries: cradle-to-grave, cradle-to-farm gate and cradle-to-consumer. Only Sanyé-Mengual et al. ( 2015a ) applied all three assessment approaches. For example, they used a cradle-to-grave approach to estimate the cost of a greenhouse structure, while a cradle-to-farm gate analysis was carried out at the production stage, and finally, they applied a cradle-to-consumer approach at the consumption point. According to our results, the most widley procedure was a cradle-to-farm gate, which was found in five of the papers (Dorr et al. 2017 ; Forchino et al. 2018 ; Llorach-Massana et al. 2016 ; Sanyé-Mengual et al. 2015a and 2015c). In contrast, Sanyé-Mengual et al. ( 2018 ) used a cradle-to-consumer or cradle-to-fork approach, and Kim and Zhang ( 2018 ) applied a cradle-to-grave approach. The only exceptions were the publications by Liaros et al. ( 2016 ), Benis et al. ( 2018 ) and Opher et al. ( 2018 ), in which the system boundaries were not described but were considered to be a cradle-to-consumer approach.

Regarding the functional unit in urban horticulture papers, the most commonly used was 1 kg, which was applied to harvested vegetables such as sweet basil (Liaros et al. 2016 ); leafy vegetables and fruits (Sanyé-Mengual et al. 2018 ); tomatoes (Llorach-Massana et al. 2016 ; Sanyé-Mengual et al. 2015a ); tomatoes and lettuce (Dorr et al. 2017 ) and lettuce, tomatoes, chilli peppers, eggplants, melons and watermelons (Sanyé-Mengual et al. 2015c ). In aquaculture, the functional unit in the study of Kim and Zhang ( 2018 , p.47) is a special case expressed as an additional 1000 kg fish production (as a result of using hot water) per year over the course of 10 years. While in aquaponics, Forchino et al. ( 2018 ) used as a functional unit, 1 kg of produced lettuce and fish (tilapia) considered as a co-product. We also found functional units not related to vegetables or fish production. For example, in Benis et al. ( 2018 ), the functional unit was 1 m 2 of rooftop used for food production or energy generation, whereas in Opher et al. ( 2018 ), it was the annual supply, reclamation and reuse of water consumed by a hypothetical city.

Various authors recommend the use of different financial tools to complement LCC analysis, such as net present value (NPV) (ISO 2008 , Kim et al. 2015 ; Assad et al. 2015 ; Carter and Keeler 2008 , Ammar et al. 2013 ; Vargas-Parra et al. 2014 ), internal rate of return (IRR) or return on investment (ROI) (Wong et al. 2003 , Fuller and Petersen, 1996 ), payback period (PBP) (Farreny et al. 2011 ; ISO 2008 ; Koroneos and Nanaki 2012 ), inflation rate (Wong et al. 2003 ; Fuller and Petersen, 1996 ), break-event point (BEP) (Jeong et al. 2015 ) and savings-to-investment ratio (SIR) (Jeong et al. 2015 ; Wong et al. 2003 ; ISO 2008 ). Because of its importance, in this section, we present some of the examples we detected for the use of financial tools. We found that 4 of 10 papers applied additional financial tools. Table 4 presents a summary of these results.

For example, Liaros et al. ( 2016 ) used the following financial tools: simple payback period (SPBP), complete payback period (CPBP), NPV, simple net present value (sNPV), benefit-to-cost ratio (BCR) and return on investment (ROI). Benis et al. ( 2018 ) estimated a 50-year discounted cash flow (DCF) for rooftop systems through NPV, IRR and PBP. Discount rate (%) and annual inflation (%) were also included in their analysis. The inflation rate was also considered in Llorach-Massana et al. ( 2016 ). Finally, Kim and Zhang ( 2018 ) analysed the economic feasibility of solar heating. The financial tools used for this purpose were escalation rate (e) and interest/discount rate (i).

In many LCC studies, a sensitivity analysis was applied as an additional analysis for assessment (Carter and Keeler 2008 ; Assad et al.2015, European Commission 2010 ). Its main purpose of this analysis is to show the effects of changing key assumptions in order to consider different possible results as a way of reducing uncertainty (ISO 2008 ). A sensitivity analysis was also used in 6 of the 10 examined papers (Kim and Zhang 2018 ; Liaros et al.2016, Sanyé-Mengual et al. 2015a , c ; Llorach-Massana et al. 2016 , Dorr et al. 2017 ). For example, in the study by Kim and Zhang ( 2018 ), a sensitivity analysis was used to evaluate various inputs, such as electricity costs, the cost of thermal solar collectors, collector efficiency, retail fish price, number of initial fish stocks and choice of species. Liaros et al. ( 2016 ) used this analysis to identify which economic factors affected the performance of a plant factory as an investment option. Sensitivity analysis was also applied in the work of Sanyé-Mengual et al. ( 2015a ) to illustrate how their results depended on crop yield and distance, while Llorach-Massana et al. ( 2016 ) and Dorr et al. ( 2017 ) used this analysis to assess the type of scenario analysed. Finally, Sanyé-Mengual et al. ( 2015c ) assessed the availability of re-used elements and the use intensity of a rooftop garden through sensitivity analysis.

Other types of additional analyses for assessment were found in the publication by Sanyé-Mengual et al. ( 2018 ). They applied an eco-efficiency analysis to study the relationship between environmental impact and economic costs.

3.2.3 Type of LCC and type of costs used by life cycle stage

Three different types of LCC analyses exist: conventional, environmental and social (Hunkeler et al.2008; UNEP/SETAC 2011 ). Conventional LCC covers all costs internal to the organization, while external costs are included in both environmental and societal LCC. Environmental LCC addresses external environmental costs that are likely to be internalized for decisions in the near future (e.g. through carbon prices or taxes). Finally, societal LCC includes all further external costs related to specific scenarios on a societal level (Skovgaard et al. 2007 ) to examine welfare losses and gains associated with the re-allocation of resources (Møller et al. 2014 ). Our results indicated that only Benis et al. ( 2018 ) applied all three types of LCC.

Since LCC takes into consideration the costs and cash flows arising from design and acquisition from operation and maintenance through to disposal (ISO 2008 , Wu and Longhurst 2011 ), four main stages should be included in the LCC analysis (Fuller and Petersen, 1996 , Jeong et al. 2015 , Kim et al. 2015 , Koroneos and Nanaki 2012 , Sanyé-Mengual et al. 2015a , Vargas-Parra et al. 2014 ).

Initial or construction stage, where initial investment costs are included

Operation stage, involving all costs accrued during the usage of the asset

Maintenance stage, which consists of the costs of repair and replacement and

End-of-life (EoL) stage, comprising the decommissioning/dismantling, demolition, disposal and recycling costs.

Table 5 shows the results of type costs used by each life cycle stage. This table also shows (in the last column) those costs that were not included in the LCC analysis:

Initial or construction stage: rooftop garden installation

Operation stage: labour costs

Maintenance stage: infrastructure maintenance, replacement costs

End-of-life (EoL) stage: recycling costs

These results are especially significant because for the first time they reveal that essential costs, like labour or the initial investment, are frequently not included. As we discuss later (see “ Discussion ” section), this is a weakness on the LCC application to UA.

3.3 Group 2: papers on cost reduction

In this section, we present the results from 3 other research papers that have optimized costs. They also used LCC for this purpose (Table 6 ).

The objective of Zidar et al. ( 2017 ) was to present a decision-support tool for green infrastructure (GI) systems to improve urban ecosystem services in Camden, USA. The authors analysed the possibility for expansion of UA through community gardens. They examined the possibility of life cycle cost reduction by looking for new funding sources for the vacant lots located at the intersection of Vine and Willard in North Camden, USA. The authors confirmed that local people involved in various green garden programmes could reduce the operation and maintenance life cycle costs.

Zhao and Meng ( 2014 ) analysed the operation costs, including the running maintenance costs, of the construction of agricultural water-saving facilities in Tianjin, China. Based on the life cycle cost theory, they found that designing innovation is the key to controlling the complex operation costs. Additionally, they investigated the effect of the investment and financing model on the design innovation process because, on the one hand, the manner of investment and financing can help to solve the construction-funding gap, whereas on the other hand, it will alter water-saving costs.

The last paper in this group, Halwatura and Jayasigne ( 2009 ), aimed to determine the ways in which an insulated roof slab could affect the energy needs for air conditioning in Sri Lanka and considered its influence on the life cycle costs. Despite the fact that this paper was related more to the construction and building sector, it was strongly connected with UA because of the opportunity for the creation of rooftop gardens to minimize the initial capital cost of the insulated roof slabs. The insulated roof slabs were expected to have additional benefits in comparison with those of a conventional roofing system, such as better cyclone resistance, low maintenance and the ability to create a greener environment with a rooftop garden. According to the authors, there was a significant reduction in the slab top temperature, with the presence of rooftop vegetation leading to energy savings, which was considered in the life cycle analysis.

3.4 Group 3: literature review of papers on LCC addresing various topic related to UA

In this section, we analysed 4 other papers that were literature reviews addressing various topics related to UA, including life cycle costs (Benis and Ferrão, 2018 ; Nguyen and Weiss 2008 ; Sanyé-Mengual et al. 2017 ; Sanyé-Mengual et al.2015 b ) (Table 7 ).

The first paper aimed to analyse the environmental, economic and social aspects of urban commercial farming as a part of urban horticulture based on case studies in northern Europe (Benis and Ferrão 2018 ). The authors examined two main points regarding the economic aspects of urban commercial farming: the level of investment and operation costs versus productivity. They confirmed that the capital expenditures of commercial farms are higher in comparison with those of conventional and rural farms and that the existence of prohibitive rents and high construction costs also reflect these results. According to the authors, the reason for the elevated operating costs was their high-energy needs and the lack of municipal subsidies (e.g. energy and water subsidies). Despite the higher costs, they demonstrated that the benefits of urban commercial farms could be found in the shortened supply chain where the logistics costs were reduced and the added value of the fresher product may have justified a higher selling price.

Nguyen and Weiss ( 2008 ) analysed vertical urban farms’ systems considering life cycle costs, design, construction, operation and infrastructure integration for environmental management and residences. The authors explained that construction and operation costs and revenues varied tremendously depending on location, market, season, demand, supply, energy costs and many other factors. According to the authors, waste reduction in construction and rationalized use of construction resources can decrease the construction time and thus decrease the overall costs. The selection of an appropriate design for the end-of-life stage could also lead to construction techniques for reducing the whole life cycle costs.

The literature review of Sanyé-Mengual et al. ( 2017 ) was based on an updated version of their previous work presented during the 7th International Aesop Sustainable Food Planning Conference in Torino, Italy (Sanyé-Mengual et al. 2015b ). Sanyé-Mengual et al. ( 2017 ) used an interdisciplinary approach to evaluate different topics related to the sustainability of URA, including its environmental impacts and economic costs. The environmental impacts were evaluated by LCA, and the economic costs were evaluated through LCC. They analysed three case studies for this purpose: a rooftop greenhouse (RTG) in Bellaterra, Spain; a community rooftop garden (CRG) in Bologna, Italy and a private rooftop garden (PRG) in Barcelona, Spain. In comparison with the rooftop greenhouses, for open-air rooftop gardens, they found lower environmental impacts and economic costs. As for the design phase of URA, the LCC and LCA results accentuated the possible contribution of URA products in improving both economic and environmental sustainability. The LCA and LCC results also highlighted the importance of the decisions made in the design phase in relation to the cultivation technique, crop choice and management.

3.5 Group 4: other papers on costs for UA

The last group is formed of 3 research papers that calculated costs for UA without specification of the methodology used. Table 8 presents a summary of the results by type of urban agricultural practice, limitations and costs included.

In the first paper, Love et al. ( 2015 ) analysed a small-scale raft aquaponics system in Baltimore (USA) to explain the operating conditions as production inputs (energy, water, and fish feed) and outputs (edible crops and fish) and their relationship. The main limitation of the study was that the authors did not consider the infrastructure/capital and the labour costs for the analysis. Other operation/production costs, such as the costs of energy, water, and fish feed, were included. The results show that raising fish created a net loss, while crop cultivation presented a net gain when comparing market prices to energy costs.Accordingly, the authors suggested that new approaches for minimizing heating for fish should be found or that new species able to survive at lower water temperatures should be used.

Algert et al. ( 2014 ) investigated the capacity of community gardens to affect food affordability in an urban setting by documenting the vegetable outputs and cost savings of community gardens in the city of San Jose, California (US). The system boundaries were limited to the production stage, excluding labour and infrastructure/capital costs. The authors calculated the economic cost by quantifying the following inputs needed for production: seeds, fertilizers, tools and soil amendments. The results of the study revealed that the vertical growth of high-yield, higher-value vegetables such as tomatoes, cucumbers, and peppers, can provide greater cost savings relative to the cost of purchasing the same amount of vegetables in a retail setting.

Finally, in the last paper, CoDyre et al. ( 2015 ) presented the results of a preliminary survey aimed at evaluating the productivity of urban gardens in the medium-sized Canadian city of Guelph. All gardens analysed were home gardens in private yards that included backyard plots and community garden spaces. The main limitation of the study was that only one city was investigated. Moreover, the analysed gardening season was subject to drought and above-average temperatures, which affected productivity. The survey aimed to assess the productivity of urban gardens in terms of land, labour and capital. Different policy outcomes were also evaluated to promote the potential of urban gardening. The results showed that, on average, tomatoes represented 37% of all harvests, followed by potatoes at 12% and squash at 7%. The authors found that the level of production and input costs varied widely across gardeners and that there was great potential in urban self-provisioning. They suggested two main methods for improving self-provisioning among the gardeners: putting more land into production and improving the gardener’s skills.

4 Discussion

In this section, we discuss the 4 most relevant findings from the “ Results ” section: (i) type of urban agriculture practice from group 1 and group 3; (ii) LCC integration with LCA/S-LCA from group 1; (iii) use of financial tools from group 1 and (iv) type of costs used at each life cycle stage from group 1, group 2 and group 4. We considered these findings the most important for the following reasons: (i) all of them are part of group 1, the major group consisting of 10 papers or 50% of 20 selected references; (ii) the most studied type of urban agriculture practice (horticulture) is important because it provides information for future directions of research of LCC in UA and finally, (iii) the life cycle stages are a fundamental part of the LCC methodology (ISO 2008 ); in this respect, the discussion on the type of costs used by life cycle stage is relevant.

Taking into account the importance of these findings, we present a discussion of each of them as follows:

Type of urban agriculture practice

LCC integration with LCA/S-LCA

Use of financial tools

Type of costs used by life cycle stage

4.1 Type of urban agricultural practice

The results of “ 3.2.1. Type of urban agricultural practice, research topic, LCC integration with LCA/S-LCA and LCC guidelines followed ” (group 1) indicated that the most studied urban agricultural practice related to LCC was urban horticulture in 8 of the 10 papers. Urban horticulture was also analysed by all the authors in “ Group 3: literature review papers on life cycle cost addresing various topics related to UA ” (see Table 7 ). This result was not surprising because Parece et al. ( 2016 ) stated that, among plant and animals used for food, the plant production represented by urban horticulture was predominant.

Within urban horticulture studies, the building-integrated forms of UA such as vertical farming or zero-acreage farming (ZFarming), including indoor farms, rooftop greenhouses, rooftop gardens and further innovative forms, are becoming more popular. The main reason for this is the insufficient space for traditional ground agriculture in many urban cities and the lack of resources needed for production, such as water and energy (Specht et al.2014; Thomaier et al. 2015 ). We found clear examples of some innovative forms of UA that use advanced technology for resource optimization in Sanyé-Mengual et al. ( 2015a ) and Benis et al. ( 2018 ). For example, Sanyé-Mengual et al. ( 2015a ) analysed the environmental and economic performances of a rooftop greenhouse (RTG) that took advantage of its integration into a sustainable building for optimizing water and energy consumption. Benis et al. ( 2018 ) evaluated the economic sustainability of high-tech rooftop greenhouse (RG) farms. Based on these results, we expect that the growing interest in innovative building-integrated forms of UA will continue in the future since the urbanization process is unavoidable (UN DESA, 2004 ). In light of this, we determined that more use and LCC research for UA is needed to evaluate the economic sustainability of these increasing building-integrated forms of UA.

4.2 LCC integration with LCA/S-LCA

One of the major findings of our study is the secondary role of LCC in its integration with LCA. Our results show that 9 of the 10 analysed papers in group 1 included both LCA and LCC analyses.