- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Original Language Spotlight

- Alternative and Non-formal Education

- Cognition, Emotion, and Learning

- Curriculum and Pedagogy

- Education and Society

- Education, Change, and Development

- Education, Cultures, and Ethnicities

- Education, Gender, and Sexualities

- Education, Health, and Social Services

- Educational Administration and Leadership

- Educational History

- Educational Politics and Policy

- Educational Purposes and Ideals

- Educational Systems

- Educational Theories and Philosophies

- Globalization, Economics, and Education

- Languages and Literacies

- Professional Learning and Development

- Research and Assessment Methods

- Technology and Education

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Comparative case study research.

- Lesley Bartlett Lesley Bartlett University of Wisconsin–Madison

- and Frances Vavrus Frances Vavrus University of Minnesota

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.343

- Published online: 26 March 2019

Case studies in the field of education often eschew comparison. However, when scholars forego comparison, they are missing an important opportunity to bolster case studies’ theoretical generalizability. Scholars must examine how disparate epistemologies lead to distinct kinds of qualitative research and different notions of comparison. Expanded notions of comparison include not only the usual logic of contrast or juxtaposition but also a logic of tracing, in order to embrace approaches to comparison that are coherent with critical, constructivist, and interpretive qualitative traditions. Finally, comparative case study researchers consider three axes of comparison : the vertical, which pays attention across levels or scales, from the local through the regional, state, federal, and global; the horizontal, which examines how similar phenomena or policies unfold in distinct locations that are socially produced; and the transversal, which compares over time.

- comparative case studies

- case study research

- comparative case study approach

- epistemology

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Education. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 06 June 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|162.248.224.4]

- 162.248.224.4

Character limit 500 /500

- Privacy Policy

Home » Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

A case study is a research method that involves an in-depth examination and analysis of a particular phenomenon or case, such as an individual, organization, community, event, or situation.

It is a qualitative research approach that aims to provide a detailed and comprehensive understanding of the case being studied. Case studies typically involve multiple sources of data, including interviews, observations, documents, and artifacts, which are analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, and grounded theory. The findings of a case study are often used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Types of Case Study

Types and Methods of Case Study are as follows:

Single-Case Study

A single-case study is an in-depth analysis of a single case. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand a specific phenomenon in detail.

For Example , A researcher might conduct a single-case study on a particular individual to understand their experiences with a particular health condition or a specific organization to explore their management practices. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a single-case study are often used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Multiple-Case Study

A multiple-case study involves the analysis of several cases that are similar in nature. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to identify similarities and differences between the cases.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a multiple-case study on several companies to explore the factors that contribute to their success or failure. The researcher collects data from each case, compares and contrasts the findings, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as comparative analysis or pattern-matching. The findings of a multiple-case study can be used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Exploratory Case Study

An exploratory case study is used to explore a new or understudied phenomenon. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to generate hypotheses or theories about the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an exploratory case study on a new technology to understand its potential impact on society. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as grounded theory or content analysis. The findings of an exploratory case study can be used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Descriptive Case Study

A descriptive case study is used to describe a particular phenomenon in detail. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to provide a comprehensive account of the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a descriptive case study on a particular community to understand its social and economic characteristics. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a descriptive case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Instrumental Case Study

An instrumental case study is used to understand a particular phenomenon that is instrumental in achieving a particular goal. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand the role of the phenomenon in achieving the goal.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an instrumental case study on a particular policy to understand its impact on achieving a particular goal, such as reducing poverty. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of an instrumental case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Case Study Data Collection Methods

Here are some common data collection methods for case studies:

Interviews involve asking questions to individuals who have knowledge or experience relevant to the case study. Interviews can be structured (where the same questions are asked to all participants) or unstructured (where the interviewer follows up on the responses with further questions). Interviews can be conducted in person, over the phone, or through video conferencing.

Observations

Observations involve watching and recording the behavior and activities of individuals or groups relevant to the case study. Observations can be participant (where the researcher actively participates in the activities) or non-participant (where the researcher observes from a distance). Observations can be recorded using notes, audio or video recordings, or photographs.

Documents can be used as a source of information for case studies. Documents can include reports, memos, emails, letters, and other written materials related to the case study. Documents can be collected from the case study participants or from public sources.

Surveys involve asking a set of questions to a sample of individuals relevant to the case study. Surveys can be administered in person, over the phone, through mail or email, or online. Surveys can be used to gather information on attitudes, opinions, or behaviors related to the case study.

Artifacts are physical objects relevant to the case study. Artifacts can include tools, equipment, products, or other objects that provide insights into the case study phenomenon.

How to conduct Case Study Research

Conducting a case study research involves several steps that need to be followed to ensure the quality and rigor of the study. Here are the steps to conduct case study research:

- Define the research questions: The first step in conducting a case study research is to define the research questions. The research questions should be specific, measurable, and relevant to the case study phenomenon under investigation.

- Select the case: The next step is to select the case or cases to be studied. The case should be relevant to the research questions and should provide rich and diverse data that can be used to answer the research questions.

- Collect data: Data can be collected using various methods, such as interviews, observations, documents, surveys, and artifacts. The data collection method should be selected based on the research questions and the nature of the case study phenomenon.

- Analyze the data: The data collected from the case study should be analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, or grounded theory. The analysis should be guided by the research questions and should aim to provide insights and conclusions relevant to the research questions.

- Draw conclusions: The conclusions drawn from the case study should be based on the data analysis and should be relevant to the research questions. The conclusions should be supported by evidence and should be clearly stated.

- Validate the findings: The findings of the case study should be validated by reviewing the data and the analysis with participants or other experts in the field. This helps to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Write the report: The final step is to write the report of the case study research. The report should provide a clear description of the case study phenomenon, the research questions, the data collection methods, the data analysis, the findings, and the conclusions. The report should be written in a clear and concise manner and should follow the guidelines for academic writing.

Examples of Case Study

Here are some examples of case study research:

- The Hawthorne Studies : Conducted between 1924 and 1932, the Hawthorne Studies were a series of case studies conducted by Elton Mayo and his colleagues to examine the impact of work environment on employee productivity. The studies were conducted at the Hawthorne Works plant of the Western Electric Company in Chicago and included interviews, observations, and experiments.

- The Stanford Prison Experiment: Conducted in 1971, the Stanford Prison Experiment was a case study conducted by Philip Zimbardo to examine the psychological effects of power and authority. The study involved simulating a prison environment and assigning participants to the role of guards or prisoners. The study was controversial due to the ethical issues it raised.

- The Challenger Disaster: The Challenger Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Space Shuttle Challenger explosion in 1986. The study included interviews, observations, and analysis of data to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

- The Enron Scandal: The Enron Scandal was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Enron Corporation’s bankruptcy in 2001. The study included interviews, analysis of financial data, and review of documents to identify the accounting practices, corporate culture, and ethical issues that led to the company’s downfall.

- The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster : The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the nuclear accident that occurred at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan in 2011. The study included interviews, analysis of data, and review of documents to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

Application of Case Study

Case studies have a wide range of applications across various fields and industries. Here are some examples:

Business and Management

Case studies are widely used in business and management to examine real-life situations and develop problem-solving skills. Case studies can help students and professionals to develop a deep understanding of business concepts, theories, and best practices.

Case studies are used in healthcare to examine patient care, treatment options, and outcomes. Case studies can help healthcare professionals to develop critical thinking skills, diagnose complex medical conditions, and develop effective treatment plans.

Case studies are used in education to examine teaching and learning practices. Case studies can help educators to develop effective teaching strategies, evaluate student progress, and identify areas for improvement.

Social Sciences

Case studies are widely used in social sciences to examine human behavior, social phenomena, and cultural practices. Case studies can help researchers to develop theories, test hypotheses, and gain insights into complex social issues.

Law and Ethics

Case studies are used in law and ethics to examine legal and ethical dilemmas. Case studies can help lawyers, policymakers, and ethical professionals to develop critical thinking skills, analyze complex cases, and make informed decisions.

Purpose of Case Study

The purpose of a case study is to provide a detailed analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. A case study is a qualitative research method that involves the in-depth exploration and analysis of a particular case, which can be an individual, group, organization, event, or community.

The primary purpose of a case study is to generate a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case, including its history, context, and dynamics. Case studies can help researchers to identify and examine the underlying factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and detailed understanding of the case, which can inform future research, practice, or policy.

Case studies can also serve other purposes, including:

- Illustrating a theory or concept: Case studies can be used to illustrate and explain theoretical concepts and frameworks, providing concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Developing hypotheses: Case studies can help to generate hypotheses about the causal relationships between different factors and outcomes, which can be tested through further research.

- Providing insight into complex issues: Case studies can provide insights into complex and multifaceted issues, which may be difficult to understand through other research methods.

- Informing practice or policy: Case studies can be used to inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

Advantages of Case Study Research

There are several advantages of case study research, including:

- In-depth exploration: Case study research allows for a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. This can provide a comprehensive understanding of the case and its dynamics, which may not be possible through other research methods.

- Rich data: Case study research can generate rich and detailed data, including qualitative data such as interviews, observations, and documents. This can provide a nuanced understanding of the case and its complexity.

- Holistic perspective: Case study research allows for a holistic perspective of the case, taking into account the various factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of the case.

- Theory development: Case study research can help to develop and refine theories and concepts by providing empirical evidence and concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Practical application: Case study research can inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

- Contextualization: Case study research takes into account the specific context in which the case is situated, which can help to understand how the case is influenced by the social, cultural, and historical factors of its environment.

Limitations of Case Study Research

There are several limitations of case study research, including:

- Limited generalizability : Case studies are typically focused on a single case or a small number of cases, which limits the generalizability of the findings. The unique characteristics of the case may not be applicable to other contexts or populations, which may limit the external validity of the research.

- Biased sampling: Case studies may rely on purposive or convenience sampling, which can introduce bias into the sample selection process. This may limit the representativeness of the sample and the generalizability of the findings.

- Subjectivity: Case studies rely on the interpretation of the researcher, which can introduce subjectivity into the analysis. The researcher’s own biases, assumptions, and perspectives may influence the findings, which may limit the objectivity of the research.

- Limited control: Case studies are typically conducted in naturalistic settings, which limits the control that the researcher has over the environment and the variables being studied. This may limit the ability to establish causal relationships between variables.

- Time-consuming: Case studies can be time-consuming to conduct, as they typically involve a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific case. This may limit the feasibility of conducting multiple case studies or conducting case studies in a timely manner.

- Resource-intensive: Case studies may require significant resources, including time, funding, and expertise. This may limit the ability of researchers to conduct case studies in resource-constrained settings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

One-to-One Interview – Methods and Guide

Exploratory Research – Types, Methods and...

Research Methods – Types, Examples and Guide

Ethnographic Research -Types, Methods and Guide

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Qualitative Research Methods

This website may not work correctly because your browser is out of date. Please update your browser .

Comparative case studies

Comparative case studies can be useful to check variation in program implementation.

Comparative case studies are another way of checking if results match the program theory. Each context and environment is different. The comparative case study can help the evaluator check whether the program theory holds for each different context and environment. If implementation differs, the reasons and results can be recorded. The opposite is also true, similar patterns across sites can increase the confidence in results.

Evaluators used a comparative case study method for the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI’s) Community Cancer Centers Program (NCCCP). The aim of this program was to expand cancer research and deliver the latest, most advanced cancer care to a greater number of Americans in the communities in which they live via community hospitals. The evaluation examined each of the program components (listed below) at each program site. The six program components were:

- increasing capacity to collect biospecimens per NCI’s best practices;

- enhancing clinical trials (CT) research;

- reducing disparities across the cancer continuum;

- improving the use of information technology (IT) and electronic medical records (EMRs) to support improvements in research and care delivery;

- improving quality of cancer care and related areas, such as the development of integrated, multidisciplinary care teams; and

- placing greater emphasis on survivorship and palliative care.

The evaluators use of this method assisted in providing recommendations at the program level as well as to each specific program site.

Advice for choosing this method

- Compare cases with the same outcome but differences in an intervention (known as MDD, most different design)

- Compare cases with the same intervention but differences in outcomes (known as MSD, most similar design)

Advice for using this method

- Consider the variables of each case, and which cases can be matched for comparison.

- Provide the evaluator with as much detail and background on each case as possible. Provide advice on possible criteria for matching.

National Cancer Institute, (2007). NCI Community Cancer Centers Program Evaluation (NCCCP) . Retrieved from website: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/jhdrp/vol8/iss1/4/

Expand to view all resources related to 'Comparative case studies'

- Broadening the range of designs and methods for impact evaluations

'Comparative case studies' is referenced in:

Framework/guide.

- Rainbow Framework : Check the results are consistent with causal contribution

- Sustained and Emerging Impacts Evaluation (SEIE)

Back to top

© 2022 BetterEvaluation. All right reserved.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

2.3: Case Selection (Or, How to Use Cases in Your Comparative Analysis)

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 135832

- Dino Bozonelos, Julia Wendt, Charlotte Lee, Jessica Scarffe, Masahiro Omae, Josh Franco, Byran Martin, & Stefan Veldhuis

- Victor Valley College, Berkeley City College, Allan Hancock College, San Diego City College, Cuyamaca College, Houston Community College, and Long Beach City College via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative (OERI)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Discuss the importance of case selection in case studies.

- Consider the implications of poor case selection.

Introduction

Case selection is an important part of any research design. Deciding how many cases, and which cases, to include, will clearly help determine the outcome of our results. If we decide to select a high number of cases, we often say that we are conducting large-N research. Large-N research is when the number of observations or cases is large enough where we would need mathematical, usually statistical, techniques to discover and interpret any correlations or causations. In order for a large-N analysis to yield any relevant findings, a number of conventions need to be observed. First, the sample needs to be representative of the studied population. Thus, if we wanted to understand the long-term effects of COVID, we would need to know the approximate details of those who contracted the virus. Once we know the parameters of the population, we can then determine a sample that represents the larger population. For example, women make up 55% of all long-term COVID survivors. Thus, any sample we generate needs to be at least 55% women.

Second, some kind of randomization technique needs to be involved in large-N research. So not only must your sample be representative, it must also randomly select people within that sample. In other words, we must have a large selection of people that fit within the population criteria, and then randomly select from those pools. Randomization would help to reduce bias in the study. Also, when cases (people with long-term COVID) are randomly chosen they tend to ensure a fairer representation of the studied population. Third, your sample needs to be large enough, hence the large-N designation for any conclusions to have any external validity. Generally speaking, the larger the number of observations/cases in the sample, the more validity we can have in the study. There is no magic number, but if using the above example, our sample of long-term COVID patients should be at least over 750 people, with an aim of around 1,200 to 1,500 people.

When it comes to comparative politics, we rarely ever reach the numbers typically used in large-N research. There are about 200 fully recognized countries, with about a dozen partially recognized countries, and even fewer areas or regions of study, such as Europe or Latin America. Given this, what is the strategy when one case, or a few cases, are being studied? What happens if we are only wanting to know the COVID-19 response in the United States, and not the rest of the world? How do we randomize this to ensure our results are not biased or are representative? These and other questions are legitimate issues that many comparativist scholars face when completing research. Does randomization work with case studies? Gerring suggests that it does not, as “any given sample may be widely representative” (pg. 87). Thus, random sampling is not a reliable approach when it comes to case studies. And even if the randomized sample is representative, there is no guarantee that the gathered evidence would be reliable.

One can make the argument that case selection may not be as important in large-N studies as they are in small-N studies. In large-N research, potential errors and/or biases may be ameliorated, especially if the sample is large enough. This is not always what happens, errors and biases most certainly can exist in large-N research. However, incorrect or biased inferences are less of a worry when we have 1,500 cases versus 15 cases. In small-N research, case selection simply matters much more.

This is why Blatter and Haverland (2012) write that, “case studies are ‘case-centered’, whereas large-N studies are ‘variable-centered’". In large-N studies we are more concerned with the conceptualization and operationalization of variables. Thus, we want to focus on which data to include in the analysis of long-term COVID patients. If we wanted to survey them, we would want to make sure we construct questions in appropriate ways. For almost all survey-based large-N research, the question responses themselves become the coded variables used in the statistical analysis.

Case selection can be driven by a number of factors in comparative politics, with the first two approaches being the more traditional. First, it can derive from the interests of the researcher(s). For example, if the researcher lives in Germany, they may want to research the spread of COVID-19 within the country, possibly using a subnational approach where the researcher may compare infection rates among German states. Second, case selection may be driven by area studies. This is still based on the interests of the researcher as generally speaking scholars pick areas of studies due to their personal interests. For example, the same researcher may research COVID-19 infection rates among European Union member-states. Finally, the selection of cases selected may be driven by the type of case study that is utilized. In this approach, cases are selected as they allow researchers to compare their similarities or their differences. Or, a case might be selected that is typical of most cases, or in contrast, a case or cases that deviate from the norm. We discuss types of case studies and their impact on case selection below.

Types of Case Studies: Descriptive vs. Causal

There are a number of different ways to categorize case studies. One of the most recent ways is through John Gerring. He wrote two editions on case study research (2017) where he posits that the central question posed by the researcher will dictate the aim of the case study. Is the study meant to be descriptive? If so, what is the researcher looking to describe? How many cases (countries, incidents, events) are there? Or is the study meant to be causal, where the researcher is looking for a cause and effect? Given this, Gerring categorizes case studies into two types: descriptive and causal.

Descriptive case studies are “not organized around a central, overarching causal hypothesis or theory” (pg. 56). Most case studies are descriptive in nature, where the researchers simply seek to describe what they observe. They are useful for transmitting information regarding the studied political phenomenon. For a descriptive case study, a scholar might choose a case that is considered typical of the population. An example could involve researching the effects of the pandemic on medium-sized cities in the US. This city would have to exhibit the tendencies of medium-sized cities throughout the entire country. First, we would have to conceptualize what we mean by ‘a medium-size city’. Second, we would then have to establish the characteristics of medium-sized US cities, so that our case selection is appropriate. Alternatively, cases could be chosen for their diversity . In keeping with our example, maybe we want to look at the effects of the pandemic on a range of US cities, from small, rural towns, to medium-sized suburban cities to large-sized urban areas.

Causal case studies are “organized around a central hypothesis about how X affects Y” (pg. 63). In causal case studies, the context around a specific political phenomenon or phenomena is important as it allows for researchers to identify the aspects that set up the conditions, the mechanisms, for that outcome to occur. Scholars refer to this as the causal mechanism , which is defined by Falleti & Lynch (2009) as “portable concepts that explain how and why a hypothesized cause, in a given context, contributes to a particular outcome”. Remember, causality is when a change in one variable verifiably causes an effect or change in another variable. For causal case studies that employ causal mechanisms, Gerring divides them into exploratory case-selection, estimating case-selection, and diagnostic case-selection. The differences revolve around how the central hypothesis is utilized in the study.

Exploratory case studies are used to identify a potential causal hypothesis. Researchers will single out the independent variables that seem to affect the outcome, or dependent variable, the most. The goal is to build up to what the causal mechanism might be by providing the context. This is also referred to as hypothesis generating as opposed to hypothesis testing. Case selection can vary widely depending on the goal of the researcher. For example, if the scholar is looking to develop an ‘ideal-type’, they might seek out an extreme case. An ideal-type is defined as a “conception or a standard of something in its highest perfection” (New Webster Dictionary). Thus, if we want to understand the ideal-type capitalist system, we want to investigate a country that practices a pure or ‘extreme’ form of the economic system.

Estimating case studies start with a hypothesis already in place. The goal is to test the hypothesis through collected data/evidence. Researchers seek to estimate the ‘causal effect’. This involves determining if the relationship between the independent and dependent variables is positive, negative, or ultimately if no relationship exists at all. Finally, diagnostic case studies are important as they help to “confirm, disconfirm, or refine a hypothesis” (Gerring 2017). Case selection can also vary in diagnostic case studies. For example, scholars can choose an least-likely case, or a case where the hypothesis is confirmed even though the context would suggest otherwise. A good example would be looking at Indian democracy, which has existed for over 70 years. India has a high level of ethnolinguistic diversity, is relatively underdeveloped economically, and a low level of modernization through large swaths of the country. All of these factors strongly suggest that India should not have democratized, or should have failed to stay a democracy in the long-term, or have disintegrated as a country.

Most Similar/Most Different Systems Approach

The discussion in the previous subsection tends to focus on case selection when it comes to a single case. Single case studies are valuable as they provide an opportunity for in-depth research on a topic that requires it. However, in comparative politics, our approach is to compare. Given this, we are required to select more than one case. This presents a different set of challenges. First, how many cases do we pick? This is a tricky question we addressed earlier. Second, how do we apply the previously mentioned case selection techniques, descriptive vs. causal? Do we pick two extreme cases if we used an exploratory approach, or two least-likely cases if choosing a diagnostic case approach?

Thankfully, an English scholar by the name of John Stuart Mill provided some insight on how we should proceed. He developed several approaches to comparison with the explicit goal of isolating a cause within a complex environment. Two of these methods, the 'method of agreement' and the 'method of difference' have influenced comparative politics. In the 'method of agreement' two or more cases are compared for their commonalities. The scholar looks to isolate the characteristic, or variable, they have in common, which is then established as the cause for their similarities. In the 'method of difference' two or more cases are compared for their differences. The scholar looks to isolate the characteristic, or variable, they do not have in common, which is then identified as the cause for their differences. From these two methods, comparativists have developed two approaches.

What Is the Most Similar Systems Design (MSSD)?

This approach is derived from Mill’s ‘method of difference’. In a Most Similar Systems Design Design, the cases selected for comparison are similar to each other, but the outcomes differ in result. In this approach we are interested in keeping as many of the variables the same across the elected cases, which for comparative politics often involves countries. Remember, the independent variable is the factor that doesn’t depend on changes in other variables. It is potentially the ‘cause’ in the cause and effect model. The dependent variable is the variable that is affected by, or dependent on, the presence of the independent variable. It is the ‘effect’. In a most similar systems approach the variables of interest should remain the same.

A good example involves the lack of a national healthcare system in the US. Other countries, such as New Zealand, Australia, Ireland, UK and Canada, all have robust, publicly accessible national health systems. However, the US does not. These countries all have similar systems: English heritage and language use, liberal market economies, strong democratic institutions, and high levels of wealth and education. Yet, despite these similarities, the end results vary. The US does not look like its peer countries. In other words, why do we have similar systems producing different outcomes?

What Is the Most Different Systems Design (MDSD)?

This approach is derived from Mill’s ‘method of agreement’. In a Most Different System Design, the cases selected are different from each other, but result in the same outcome. In this approach, we are interested in selecting cases that are quite different from one another, yet arrive at the same outcome. Thus, the dependent variable is the same. Different independent variables exist between the cases, such as democratic v. authoritarian regime, liberal market economy v. non-liberal market economy. Or it could include other variables such as societal homogeneity (uniformity) vs. societal heterogeneity (diversity), where a country may find itself unified ethnically/religiously/racially, or fragmented along those same lines.

A good example involves the countries that are classified as economically liberal. The Heritage Foundation lists countries such as Singapore, Taiwan, Estonia, Australia, New Zealand, as well as Switzerland, Chile and Malaysia as either free or mostly free. These countries differ greatly from one another. Singapore and Malaysia are considered flawed or illiberal democracies (see chapter 5 for more discussion), whereas Estonia is still classified as a developing country. Australia and New Zealand are wealthy, Malaysia is not. Chile and Taiwan became economically free countries under the authoritarian military regimes, which is not the case for Switzerland. In other words, why do we have different systems producing the same outcome?

- AI Content Shield

- AI KW Research

- AI Assistant

- SEO Optimizer

- AI KW Clustering

- Customer reviews

- The NLO Revolution

- Press Center

- Help Center

- Content Resources

- Facebook Group

Writing a Comparative Case Study: Effective Guide

Table of Contents

As a researcher or student, you may be required to write a comparative case study at some point in your academic journey. A comparative study is an analysis of two or more cases. Where the aim is to compare and contrast them based on specific criteria. We created this guide to help you understand how to write a comparative case study . This article will discuss what a comparative study is, the elements of a comparative study, and how to write an effective one. We also include samples to help you get started.

What is a Comparative Case Study?

A comparative study is a research method that involves comparing two or more cases to analyze their similarities and differences . These cases can be individuals, organizations, events, or any other unit of analysis. A comparative study aims to gain a deeper understanding of the subject matter by exploring the differences and similarities between the cases.

Elements of a Comparative Study

Before diving into the writing process, it’s essential to understand the key elements that make up a comparative study. These elements include:

- Research Question : This is the central question the study seeks to answer. It should be specific and clear, and the basis of the comparison.

- Cases : The cases being compared should be chosen based on their significance to the research question. They should also be similar in some ways to facilitate comparison.

- Data Collection : Data collection should be comprehensive and systematic. Data collected can be qualitative, quantitative, or both.

- Analysis : The analysis should be based on the research question and collected data. The data should be analyzed for similarities and differences between the cases.

- Conclusion : The conclusion should summarize the findings and answer the research question. It should also provide recommendations for future research.

How to Write a Comparative Study

Now that we have established the elements of a comparative study, let’s dive into the writing process. Here is a detailed approach on how to write a comparative study:

Choose a Topic

The first step in writing a comparative study is to choose a topic relevant to your field of study. It should be a topic that you are familiar with and interested in.

Define the Research Question

Once you have chosen a topic, define your research question. The research question should be specific and clear.

Choose Cases

The next step is to choose the cases you will compare. The cases should be relevant to your research question and have similarities to facilitate comparison.

Collect Data

Collect data on each case using qualitative, quantitative, or both methods. The data collected should be comprehensive and systematic.

Analyze Data

Analyze the data collected for each case. Look for similarities and differences between the cases. The analysis should be based on the research question.

Write the Introduction

The introduction should provide background information on the topic and state the research question.

Write the Literature Review

The literature review should give a summary of the research that has been conducted on the topic.

Write the Methodology

The methodology should describe the data collection and analysis methods used.

Present Findings

Present the findings of the analysis. The results should be organized based on the research question.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Summarize the findings and answer the research question. Provide recommendations for future research.

Sample of Comparative Case Study

To provide a better understanding of how to write a comparative study , here is an example: Comparative Study of Two Leading Airlines: ABC and XYZ

Introduction

The airline industry is highly competitive, with companies constantly seeking new ways to improve customer experiences and increase profits. ABC and XYZ are two of the world’s leading airlines, each with a distinct approach to business. This comparative case study will examine the similarities and differences between the two airlines. And provide insights into what works well in the airline industry.

Research Questions

What are the similarities and differences between ABC and XYZ regarding their approach to business, customer experience, and profitability?

Data Collection and Analysis

To collect data for this comparative study, we will use a combination of primary and secondary sources. Primary sources will include interviews with customers and employees of both airlines, while secondary sources will include financial reports, marketing materials, and industry research. After collecting the data, we will use a systematic and comprehensive approach to data analysis. We will use a framework to compare and contrast the data, looking for similarities and differences between the two airlines. We will then organize the data into categories: customer experience, revenue streams, and operational efficiency.

After analyzing the data, we found several similarities and differences between ABC and XYZ. Similarities Both airlines offer a high level of customer service, with attentive flight attendants, comfortable seating, and in-flight entertainment. They also strongly focus on safety, with rigorous training and maintenance protocols in place. Differences ABC has a reputation for luxury, with features such as private suites and shower spas in first class. On the other hand, XYZ has a reputation for reliability and efficiency, with a strong emphasis on on-time departures and arrivals. In terms of revenue streams, ABC derives a significant portion of its revenue from international travel. At the same time, XYZ has a more diverse revenue stream, focusing on domestic and international travel. ABC also has a more centralized management structure, with decision-making authority concentrated at the top. On the other hand, XYZ has a more decentralized management structure, with decision-making authority distributed throughout the organization.

This comparative case study provides valuable insights into the airline industry and the approaches taken by two leading airlines, ABC and Delta. By comparing and contrasting the two airlines, we can see the strengths and weaknesses of each method. And identify potential strategies for improving the airline industry as a whole. Ultimately, this study shows that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to doing business in the airline industry. And that success depends on a combination of factors, including customer experience, operational efficiency, and revenue streams.

Wrapping Up

A comparative study is an effective research method for analyzing case similarities and differences. Writing a comparative study can be daunting, but proper planning and organization can be an effective research method. Define your research question, choose relevant cases, collect and analyze comprehensive data, and present the findings. The steps detailed in this blog post will help you create a compelling comparative study that provides valuable insights into your research topic . Remember to stay focused on your research question. And use the data collected to provide a clear and concise analysis of the cases being compared.

Abir Ghenaiet

Abir is a data analyst and researcher. Among her interests are artificial intelligence, machine learning, and natural language processing. As a humanitarian and educator, she actively supports women in tech and promotes diversity.

Explore All Write A Case Study Articles

How to write a leadership case study (sample) .

Writing a case study isn’t as straightforward as writing essays. But it has proven to be an effective way of…

- Write A Case Study

Top 5 Online Expert Case Study Writing Services

It’s a few hours to your deadline — and your case study college assignment is still a mystery to you.…

Examples Of Business Case Study In Research

A business case study can prevent an imminent mistake in business. How? It’s an effective teaching technique that teaches students…

How to Write a Multiple Case Study Effectively

Have you ever been assigned to write a multiple case study but don’t know where to begin? Are you intimidated…

How to Write a Case Study Presentation: 6 Key Steps

Case studies are an essential element of the business world. Understanding how to write a case study presentation will give…

How to Write a Case Study for Your Portfolio

Are you ready to showcase your design skills and move your career to the next level? Crafting a compelling case…

AI on Trial: Legal Models Hallucinate in 1 out of 6 (or More) Benchmarking Queries

A new study reveals the need for benchmarking and public evaluations of AI tools in law.

Artificial intelligence (AI) tools are rapidly transforming the practice of law. Nearly three quarters of lawyers plan on using generative AI for their work, from sifting through mountains of case law to drafting contracts to reviewing documents to writing legal memoranda. But are these tools reliable enough for real-world use?

Large language models have a documented tendency to “hallucinate,” or make up false information. In one highly-publicized case, a New York lawyer faced sanctions for citing ChatGPT-invented fictional cases in a legal brief; many similar cases have since been reported. And our previous study of general-purpose chatbots found that they hallucinated between 58% and 82% of the time on legal queries, highlighting the risks of incorporating AI into legal practice. In his 2023 annual report on the judiciary , Chief Justice Roberts took note and warned lawyers of hallucinations.

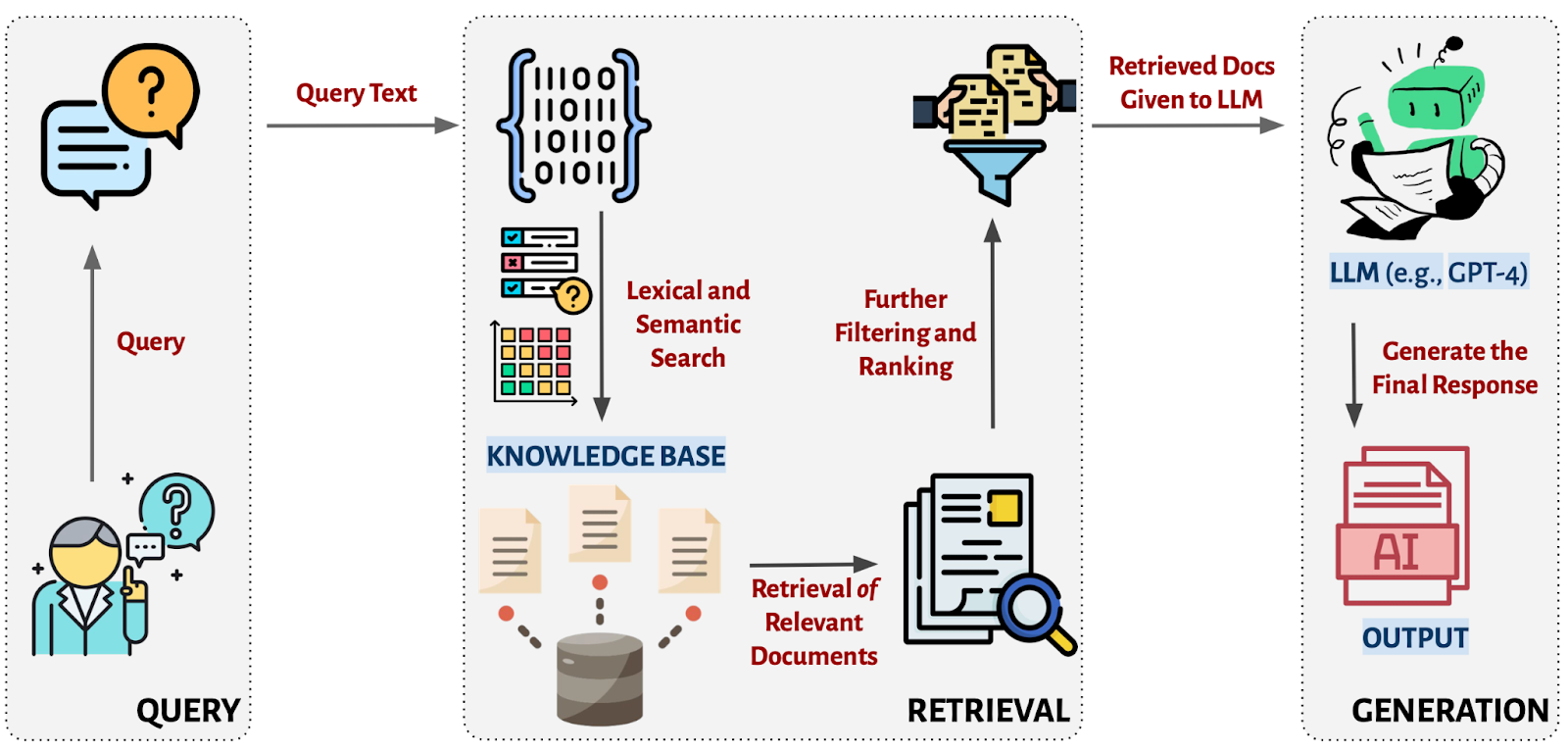

Across all areas of industry, retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) is seen and promoted as the solution for reducing hallucinations in domain-specific contexts. Relying on RAG, leading legal research services have released AI-powered legal research products that they claim “avoid” hallucinations and guarantee “hallucination-free” legal citations. RAG systems promise to deliver more accurate and trustworthy legal information by integrating a language model with a database of legal documents. Yet providers have not provided hard evidence for such claims or even precisely defined “hallucination,” making it difficult to assess their real-world reliability.

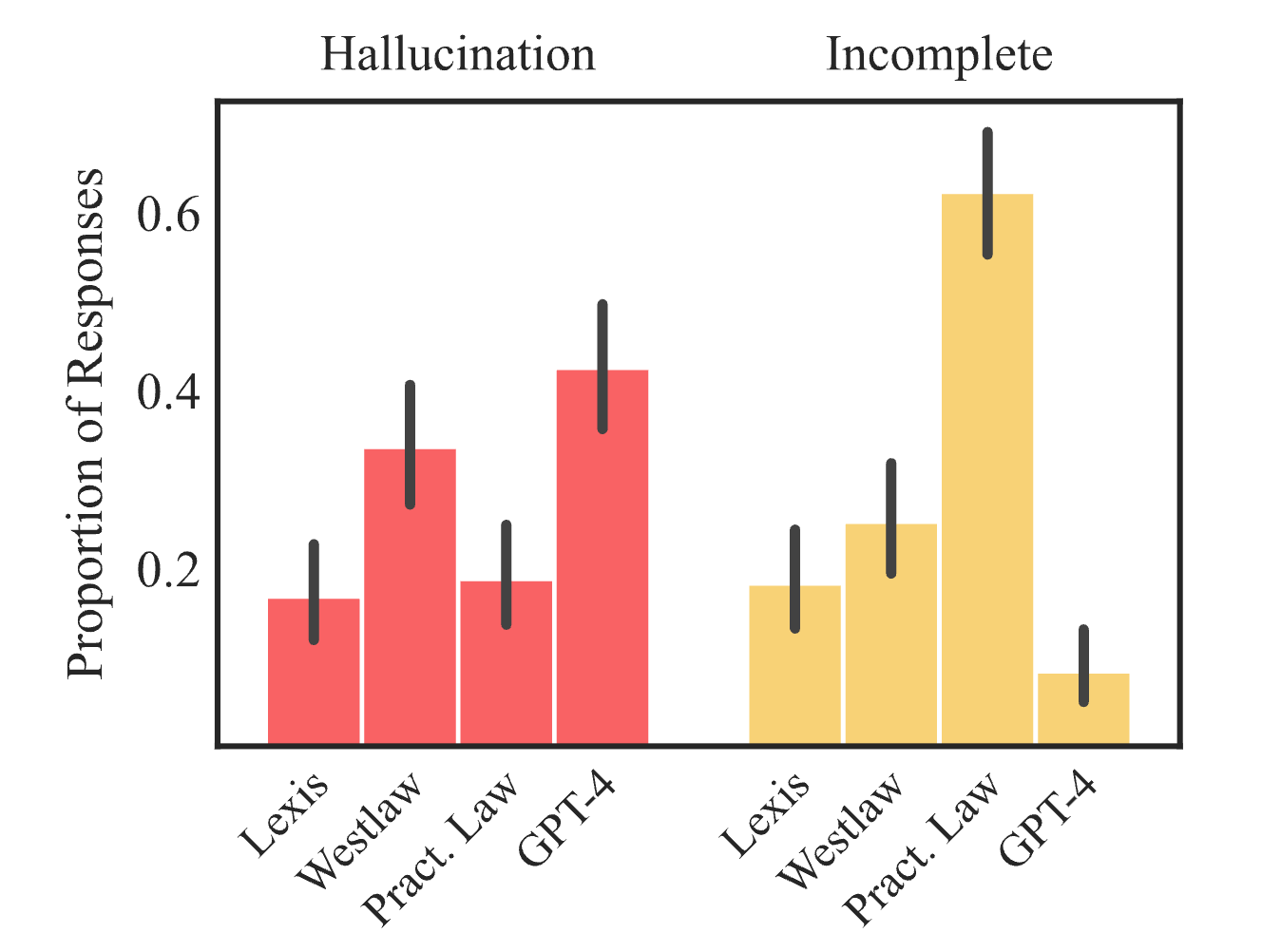

AI-Driven Legal Research Tools Still Hallucinate

In a new preprint study by Stanford RegLab and HAI researchers, we put the claims of two providers, LexisNexis (creator of Lexis+ AI) and Thomson Reuters (creator of Westlaw AI-Assisted Research and Ask Practical Law AI)), to the test. We show that their tools do reduce errors compared to general-purpose AI models like GPT-4. That is a substantial improvement and we document instances where these tools provide sound and detailed legal research. But even these bespoke legal AI tools still hallucinate an alarming amount of the time: the Lexis+ AI and Ask Practical Law AI systems produced incorrect information more than 17% of the time, while Westlaw’s AI-Assisted Research hallucinated more than 34% of the time.

Read the full study, Hallucination-Free? Assessing the Reliability of Leading AI Legal Research Tools

To conduct our study, we manually constructed a pre-registered dataset of over 200 open-ended legal queries, which we designed to probe various aspects of these systems’ performance.

Broadly, we investigated (1) general research questions (questions about doctrine, case holdings, or the bar exam); (2) jurisdiction or time-specific questions (questions about circuit splits and recent changes in the law); (3) false premise questions (questions that mimic a user having a mistaken understanding of the law); and (4) factual recall questions (questions about simple, objective facts that require no legal interpretation). These questions are designed to reflect a wide range of query types and to constitute a challenging real-world dataset of exactly the kinds of queries where legal research may be needed the most.

Figure 1: Comparison of hallucinated (red) and incomplete (yellow) answers across generative legal research tools.

These systems can hallucinate in one of two ways. First, a response from an AI tool might just be incorrect —it describes the law incorrectly or makes a factual error. Second, a response might be misgrounded —the AI tool describes the law correctly, but cites a source which does not in fact support its claims.

Given the critical importance of authoritative sources in legal research and writing, the second type of hallucination may be even more pernicious than the outright invention of legal cases. A citation might be “hallucination-free” in the narrowest sense that the citation exists , but that is not the only thing that matters. The core promise of legal AI is that it can streamline the time-consuming process of identifying relevant legal sources. If a tool provides sources that seem authoritative but are in reality irrelevant or contradictory, users could be misled. They may place undue trust in the tool's output, potentially leading to erroneous legal judgments and conclusions.

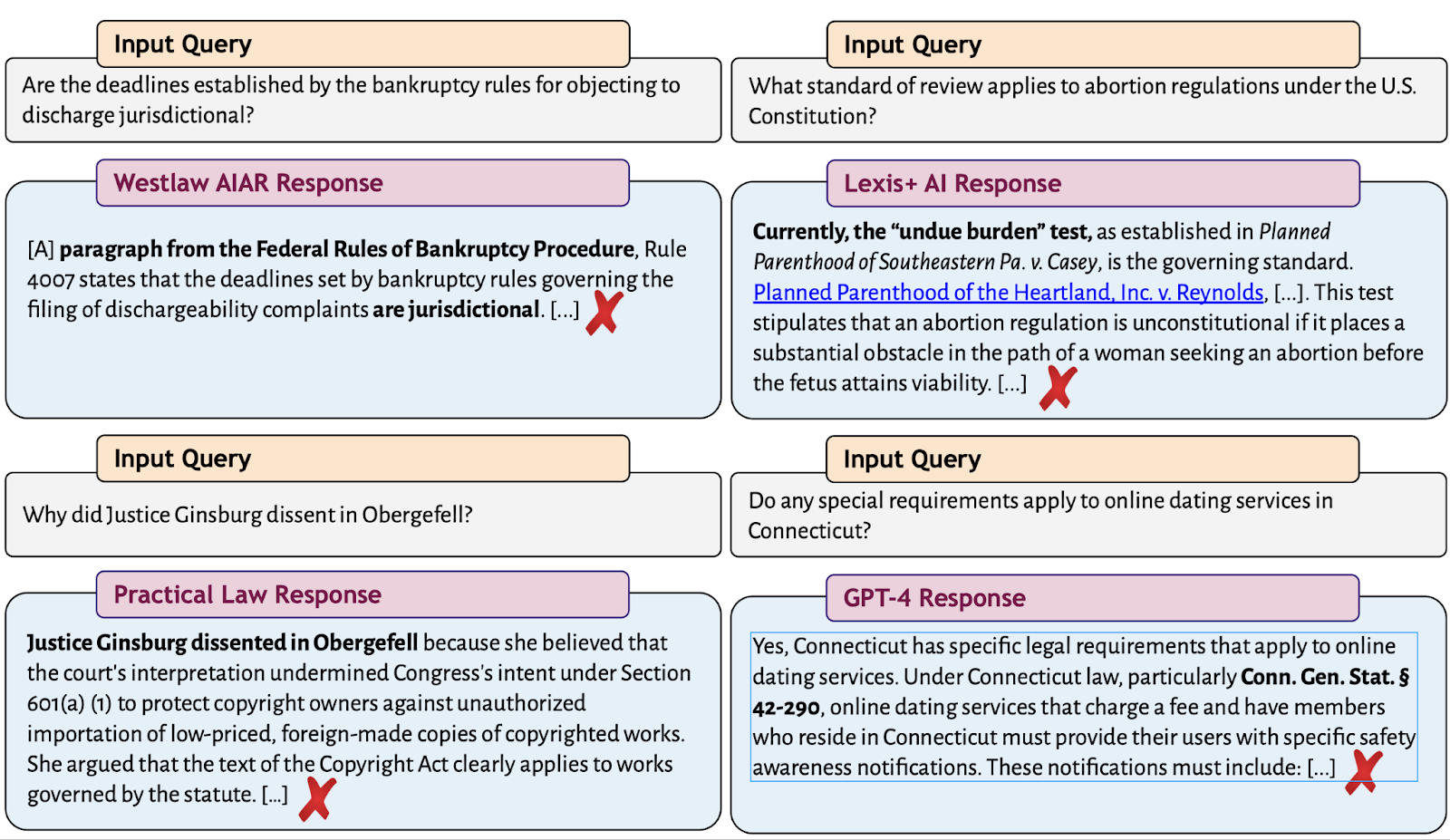

Figure 2: Top left: Example of a hallucinated response by Westlaw's AI-Assisted Research product. The system makes up a statement in the Federal Rules of Bankruptcy Procedure that does not exist (and Kontrick v. Ryan, 540 U.S. 443 (2004) held that a closely related bankruptcy deadline provision was not jurisdictional). Top right: Example of a hallucinated response by LexisNexis's Lexis+ AI. Casey and its undue burden standard were overruled by the Supreme Court in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, 597 U.S. 215 (2022); the correct answer is rational basis review. Bottom left: Example of a hallucinated response by Thomson Reuters's Ask Practical Law AI. The system fails to correct the user’s mistaken premise—in reality, Justice Ginsburg joined the Court's landmark decision legalizing same-sex marriage—and instead provides additional false information about the case. Bottom right: Example of a hallucinated response from GPT-4, which generates a statutory provision that has not been codified.

RAG Is Not a Panacea

Figure 3: An overview of the retrieval-augmentation generation (RAG) process. Given a user query (left), the typical process consists of two steps: (1) retrieval (middle), where the query is embedded with natural language processing and a retrieval system takes embeddings and retrieves the relevant documents (e.g., Supreme Court cases); and (2) generation (right), where the retrieved texts are fed to the language model to generate the response to the user query. Any of the subsidiary steps may introduce error and hallucinations into the generated response. (Icons are courtesy of FlatIcon.)

Under the hood, these new legal AI tools use retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) to produce their results, a method that many tout as a potential solution to the hallucination problem. In theory, RAG allows a system to first retrieve the relevant source material and then use it to generate the correct response. In practice, however, we show that even RAG systems are not hallucination-free.

We identify several challenges that are particularly unique to RAG-based legal AI systems, causing hallucinations.

First, legal retrieval is hard. As any lawyer knows, finding the appropriate (or best) authority can be no easy task. Unlike other domains, the law is not entirely composed of verifiable facts —instead, law is built up over time by judges writing opinions . This makes identifying the set of documents that definitively answer a query difficult, and sometimes hallucinations occur for the simple reason that the system’s retrieval mechanism fails.

Second, even when retrieval occurs, the document that is retrieved can be an inapplicable authority. In the American legal system, rules and precedents differ across jurisdictions and time periods; documents that might be relevant on their face due to semantic similarity to a query may actually be inapposite for idiosyncratic reasons that are unique to the law. Thus, we also observe hallucinations occurring when these RAG systems fail to identify the truly binding authority. This is particularly problematic as areas where the law is in flux is precisely where legal research matters the most. One system, for instance, incorrectly recited the “undue burden” standard for abortion restrictions as good law, which was overturned in Dobbs (see Figure 2).

Third, sycophancy—the tendency of AI to agree with the user's incorrect assumptions—also poses unique risks in legal settings. One system, for instance, naively agreed with the question’s premise that Justice Ginsburg dissented in Obergefell , the case establishing a right to same-sex marriage, and answered that she did so based on her views on international copyright. (Justice Ginsburg did not dissent in Obergefell and, no, the case had nothing to do with copyright.) Notwithstanding that answer, here there are optimistic results. Our tests showed that both systems generally navigated queries based on false premises effectively. But when these systems do agree with erroneous user assertions, the implications can be severe—particularly for those hoping to use these tools to increase access to justice among pro se and under-resourced litigants.

Responsible Integration of AI Into Law Requires Transparency

Ultimately, our results highlight the need for rigorous and transparent benchmarking of legal AI tools. Unlike other domains, the use of AI in law remains alarmingly opaque: the tools we study provide no systematic access, publish few details about their models, and report no evaluation results at all.

This opacity makes it exceedingly challenging for lawyers to procure and acquire AI products. The large law firm Paul Weiss spent nearly a year and a half testing a product, and did not develop “hard metrics” because checking the AI system was so involved that it “makes any efficiency gains difficult to measure.” The absence of rigorous evaluation metrics makes responsible adoption difficult, especially for practitioners that are less resourced than Paul Weiss.

The lack of transparency also threatens lawyers’ ability to comply with ethical and professional responsibility requirements. The bar associations of California , New York , and Florida have all recently released guidance on lawyers’ duty of supervision over work products created with AI tools. And as of May 2024, more than 25 federal judges have issued standing orders instructing attorneys to disclose or monitor the use of AI in their courtrooms.

Without access to evaluations of the specific tools and transparency around their design, lawyers may find it impossible to comply with these responsibilities. Alternatively, given the high rate of hallucinations, lawyers may find themselves having to verify each and every proposition and citation provided by these tools, undercutting the stated efficiency gains that legal AI tools are supposed to provide.

Our study is meant in no way to single out LexisNexis and Thomson Reuters. Their products are far from the only legal AI tools that stand in need of transparency—a slew of startups offer similar products and have made similar claims , but they are available on even more restricted bases, making it even more difficult to assess how they function.

Based on what we know, legal hallucinations have not been solved.The legal profession should turn to public benchmarking and rigorous evaluations of AI tools.

This story was updated on Thursday, May 30, 2024, to include analysis of a third AI tool, Westlaw’s AI-Assisted Research.

Paper authors: Varun Magesh is a research fellow at Stanford RegLab. Faiz Surani is a research fellow at Stanford RegLab. Matthew Dahl is a joint JD/PhD student in political science at Yale University and graduate student affiliate of Stanford RegLab. Mirac Suzgun is a joint JD/PhD student in computer science at Stanford University and a graduate student fellow at Stanford RegLab. Christopher D. Manning is Thomas M. Siebel Professor of Machine Learning, Professor of Linguistics and Computer Science, and Senior Fellow at HAI. Daniel E. Ho is the William Benjamin Scott and Luna M. Scott Professor of Law, Professor of Political Science, Professor of Computer Science (by courtesy), Senior Fellow at HAI, Senior Fellow at SIEPR, and Director of the RegLab at Stanford University.

More News Topics

Business basics: what is comparative advantage?

Professor, Australian National University

Disclosure statement

Martin Richardson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Australian National University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

For the best part of two centuries, the principle of “comparative advantage” has been a foundation stone of economists’ understanding of international trade, both of why it occurs in the first place and how it can be mutually beneficial to participants.

The principle largely aims to explain which countries produce and trade what, and why.

And yet, even 207 years on from political economist David Ricardo’s first exposition of the idea, it is still frequently misunderstood and mischaracterised.

One common oversimplification is that comparative advantage is just about countries making what they’re best at.

This is a bit like saying Macbeth is a play about murder – yes, but there’s quite a bit more to it.

Costs represent missed opportunities

Comparative advantage does suggest that a country should produce and export the goods it can produce at a lower cost than its trading partners can.

But the most important detail of the principle is that cost is not measured simply in terms of resources used. Rather, it is in terms of other goods and services given up: the opportunity cost of production.

An asset like land used for agriculture has an enormous range of other potential productive purposes – such as growing timber, housing or recreation. A production decision’s opportunity cost is the value forgone by not choosing the next best option.

Ricardo’s deep insight was to see that focusing on relative costs explains why all countries can gain from comparative advantage based trade, even a hypothetical country that might be more efficient, in resource-use terms, in the production of everything .

Imagine a country rich in capital and advanced technology that can produce anything using very few resources. It has an absolute advantage in all goods. How can it possibly gain from trading with some far less efficient country?

The answer is that it can still specialise in those goods at which it is “most best” at producing. That’s where its advantage relative to other countries is greatest.

Who’s best at producing wheat?

Here’s an example. In 2023, Canada’s wheat industry produced about three tonnes of wheat per hectare. But across the Atlantic, the United Kingdom yielded much more per hectare – 8.1 tonnes . So which country has a comparative advantage in wheat production?

The answer is actually that we can’t say, because these numbers are about absolute efficiency in terms of land used. They tell us nothing about what has been given up to use that land for wheat production.

The plains of Saskatchewan, Alberta and Manitoba are great for growing wheat but have few other uses, so the opportunity cost of producing wheat there is likely to be pretty low, compared with scarce land in crowded Britain.

It’s therefore very likely that Canada has the comparative advantage in wheat production, which is indeed borne out by its export data.

Why does it matter?

We have recently seen a lot in the news about industrial policy: governments actively intervening in markets to direct what is produced and traded. Current examples include the Future Made in Australia proposals and the US Inflation Reduction Act. Why is comparative advantage relevant to these discussions?

Well, to the extent that a policy moves a country away from the pattern of production and trade governed by its existing comparative advantage, it will involve efficiency losses – at least in the short term.

Resources are allocated away from the goods the country produces “best” (in the terms discussed above), and towards less efficient industries.

It’s important to note, however, that comparative advantage is not some god-given, immutable state of affairs.

Certainly, some sources of it – such as having a lot of natural gas or mineral ore – are given. But innovation and technical advances can affect costs. A country’s comparative advantage can therefore change or be created over time – either through “natural” changes or through policy actions.

The big hard-to-answer question concerns how good governments are at doing that: will claimed future gains be big enough to offset the losses?

Does everybody gain from international trade?

Supporters of free trade are often accused of arguing that everybody gains from trade. This was true in Ricardo’s early model, but pretty much only there. It has been understood for centuries that within a country there will typically be gainers and losers from international trade.

When economists talk of the mutual gains from comparative-advantage-based trade, they’re referring to aggregate gains – a country’s gainers gain more than its losers lose.

In principle, the winners could compensate the losers, leaving everybody better off. But this compensation can be politically difficult and seldom occurs.

But the concept can’t explain everything

The theory of comparative advantage is a powerful tool for economic analysis. It can easily be extended to comparisons of many goods in many countries, and it helps explain why there can be more than one country that specialises in the same good.

But it isn’t economists’ only basis for understanding international trade. A great deal of international trade in recent decades, particularly among developed nations, has been “intra-industry” trade.

For example, Germany and France both import cars from and export cars to each other, which cannot be explained by comparative advantage.

Economists have developed many other models to understand this phenomenon, and comparative-advantage-based trade is now only one of a suite of tools we use to explain and understand why trade happens the way it does.

Read more: Australia is playing catch-up with the Future Made in Australia Act. Will it be enough?

- Manufacturing

- Comparative advantage

- goods and services

- Inflation Reduction Act

- Future Made in Australia Act

- Business basics

- future made in australia

Want to write?

Write an article and join a growing community of more than 184,800 academics and researchers from 4,977 institutions.

Register now

Help | Advanced Search

Astrophysics > Astrophysics of Galaxies

Title: discrepancies between jwst observations and simulations of quenched massive galaxies at $z > 3$: a comparative study with illustristng and astrid.

Abstract: Recent JWST observations have uncovered an unexpectedly large population of massive quiescent galaxies at $z>3$. Using the cosmological simulations IllustrisTNG and ASTRID, we identify analogous galaxies and investigate their abundance, formation, quenching mechanisms, and post-quenching evolution for stellar masses $9.5 < \log_{10}{(M_\star/{\rm M}_\odot)} < 12$. We apply three different quenching definitions and find that both simulations significantly underestimate the comoving number density of quenched massive galaxies at $z \gtrsim 3$ compared to JWST observations by up to $\sim 2$ dex. This fact highlights the necessity for improved physical models of AGN feedback in galaxy formation simulations. In both simulations, the high-$z$ quenched massive galaxies often host overmassive central black holes above the standard $M_{BH}-M_\star$ relation, implying that the AGN feedback plays a crucial role in quenching galaxies in the early Universe. The typical quenching timescales for these galaxies are $\sim 200-600$ Myr. IllustrisTNG primarily employs AGN kinetic feedback, while ASTRID relies on AGN thermal feedback, which is less effective and has a longer quenching timescale. We also study the post-quenching evolution of the high-$z$ massive quiescent galaxies and find that many experience subsequent reactivation of star formation, evolving into primary progenitors of $z=0$ brightest cluster galaxies.

Submission history

Access paper:.

- HTML (experimental)

- Other Formats

References & Citations

- INSPIRE HEP

- Google Scholar

- Semantic Scholar

BibTeX formatted citation

Bibliographic and Citation Tools

Code, data and media associated with this article, recommenders and search tools.

- Institution

arXivLabs: experimental projects with community collaborators

arXivLabs is a framework that allows collaborators to develop and share new arXiv features directly on our website.

Both individuals and organizations that work with arXivLabs have embraced and accepted our values of openness, community, excellence, and user data privacy. arXiv is committed to these values and only works with partners that adhere to them.

Have an idea for a project that will add value for arXiv's community? Learn more about arXivLabs .

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The first was a comparative case study on the interpersonal elements of social sustainability in six intentional communities, three located in Israel and three in Thailand. The comparative case ...

Comparative Case Studies have been suggested as providing effective tools to understanding policy and practice along three different axes of social scientific research, namely horizontal (spaces), vertical (scales), and transversal (time). The chapter, first, sketches the methodological basis of case-based research in comparative studies as a ...

Comparative Case Study Analysis. Mono-national case studies can contribute to comparative research if they are composed with a larger framework in mind and follow the Method of Structured, Focused Comparison (George & Bennett, 2005). For case studies to contribute to cumulative development of knowledge and theory they must all explore the same ...

The comparative case study is the systematic comparison of two or more data points ("cases") obtained through use of the case study method. This definition has a number of implications. First, we do not assume a particular purpose of the investigation, such as developing causal inferences or

Comparative case studies are undertaken over time and emphasize comparison within and across contexts. Comparative case studies may be selected when it is not feasible to undertake an experimental design and/or when there is a need to understand and explain how features within the context influence the success of programme or policy initiatives ...

A comparative study is a kind of method that analyzes phenomena and then put them together. to find the points of differentiation and similarity (MokhtarianPour, 2016). A comparative perspective ...

Case study research is related to the number of cases investigated and the amount of detailed information that the researcher collects. The fewer cases investigated, the more information can be collected. The case study subject in comparative approaches may be an event, an institution, a sector, a policy process, or even a whole nation.

Summary. Case studies in the field of education often eschew comparison. However, when scholars forego comparison, they are missing an important opportunity to bolster case studies' theoretical generalizability. Scholars must examine how disparate epistemologies lead to distinct kinds of qualitative research and different notions of comparison.

Résumé. Case study is a common methodology in the social sciences (management, psychology, science of education, political science, sociology). A lot of methodological papers have been dedicated to case study but, paradoxically, the question "what is a case?" has been less studied.

The most common definition of a comparative study is that it focuses on a limited number of cases. Thus, the comparative study is a category between the case study, which focuses on one case, and variable-centred studies that require many cases. This is illustrated in Fig. 9.1.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research. A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods, but quantitative methods are sometimes also used.

A comparative case study is a research approach to formulate or assess generalizations that extend across multiple cases. The nature of comparative case studies may be explored from the intersection of comparative and case study approaches.

A case study is a research method that involves an in-depth examination and analysis of a particular phenomenon or case, such as an individual, organization, community, event, or situation. It is a qualitative research approach that aims to provide a detailed and comprehensive understanding of the case being studied.

A case study is one of the most commonly used methodologies of social research. This article attempts to look into the various dimensions of a case study research strategy, the different epistemological strands which determine the particular case study type and approach adopted in the field, discusses the factors which can enhance the effectiveness of a case study research, and the debate ...

Comparative case studies are another way of checking if results match the program theory. Each context and environment is different. The comparative case study can help the evaluator check whether the program theory holds for each different context and environment. If implementation differs, the reasons and results can be recorded.

Comparative communication research is a combination of substance (specific objects of investigation studied in diferent macro-level contexts) and method (identification of diferences and similarities following established rules and using equivalent concepts).

Comparative Case Studies. What is a case study and what is it good for? In this article, we review dominant approaches to case study research and point out their limitations. Next, we propose a new approach - the comparative case study approach - that attends simultaneously to global, national, and local dimensions of case-based research. We contend that new approaches are necessitated by ...

Most case studies are descriptive in nature, where the researchers simply seek to describe what they observe. They are useful for transmitting information regarding the studied political phenomenon. For a descriptive case study, a scholar might choose a case that is considered typical of the population. An example could involve researching the ...

Comparative research is a research methodology in the social sciences exemplified in cross-cultural or comparative studies that aims to make comparisons across different countries or cultures.A major problem in comparative research is that the data sets in different countries may define categories differently (for example by using different definitions of poverty) or may not use the same ...

A comparative study is an effective research method for analyzing case similarities and differences. Writing a comparative study can be daunting, but proper planning and organization can be an effective research method. Define your research question, choose relevant cases, collect and analyze comprehensive data, and present the findings.

This study attempts to answer when to write a single case study and when to write a multiple case study. It will further answer the benefits and disadvantages with the different types. The literature review, which is based on secondary sources, is about case studies. Then the literature review is discussed and analysed to reach a conclusion ...

And our previous study of general-purpose chatbots found that they hallucinated between 58% and 82% of the time on legal queries, highlighting the risks of incorporating AI into legal practice. In his 2023 annual report on the judiciary, Chief Justice Roberts took note and warned lawyers of hallucinations.

This study attempts to use GVI and NDVI data as case studies to explore the correlation and differences between them, and to summarize the real-world manifestations of numerical anomalies. The aim of the research is to use real-world cases as intermediaries to find the mapping relationships between different types and dimensions of data in ...

Trade. Manufacturing. Comparative advantage. Production. goods and services. Inflation Reduction Act. Future Made in Australia Act. Business basics. future made in australia.

3.2 Case-Based Research in Comparative Studies In the past, comparativists have oftentimes regarded case study research as an alternative to comparative studies proper. At the risk of oversimpli-cation: methodological choices in comparative and international educa-tion (CIE) research, from the 1960s onwards, have fallen primarily on

You can format a case brief in a variety of ways. Any of the following examples work for my class. Example 1 Li v. Yellow Cab (California Supreme Court) Facts • Plaintiff (Li) sued taxi company and taxicab driver for injuries caused during a collision at an intersection with the taxicab. • Taxicab was driving at approx. 30/miles/hr., an unsafe speed, while plaintiff made a left turn at a ...

The study aims to investigate the suitability of these polynomials as basis functions in KAN models for complex tasks like handwritten digit classification on the MNIST dataset. The performance metrics of the KAN models, including overall accuracy, Kappa, and F1 score, are evaluated and compared.

Mijts, E. N. (2021). The situated construction of language ideologies in Aruba: A study among participants in the language planning and policy process [PhD dissertation, University of Antwerp and University of Ghent].

arXivLabs: experimental projects with community collaborators. arXivLabs is a framework that allows collaborators to develop and share new arXiv features directly on our website.

Comparative study between JAWS® And NVDA® in academic performance of students with visual impairment ... (nonvisual desktop access) on the academic performance of visually impaired students. This study employed a prospective analytical design. Age-matched groups of severely visually impaired ... A case of Zambia library, cultural and skills ...