- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Original Language Spotlight

- Alternative and Non-formal Education

- Cognition, Emotion, and Learning

- Curriculum and Pedagogy

- Education and Society

- Education, Change, and Development

- Education, Cultures, and Ethnicities

- Education, Gender, and Sexualities

- Education, Health, and Social Services

- Educational Administration and Leadership

- Educational History

- Educational Politics and Policy

- Educational Purposes and Ideals

- Educational Systems

- Educational Theories and Philosophies

- Globalization, Economics, and Education

- Languages and Literacies

- Professional Learning and Development

- Research and Assessment Methods

- Technology and Education

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Comparative case study research.

- Lesley Bartlett Lesley Bartlett University of Wisconsin–Madison

- and Frances Vavrus Frances Vavrus University of Minnesota

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.343

- Published online: 26 March 2019

Case studies in the field of education often eschew comparison. However, when scholars forego comparison, they are missing an important opportunity to bolster case studies’ theoretical generalizability. Scholars must examine how disparate epistemologies lead to distinct kinds of qualitative research and different notions of comparison. Expanded notions of comparison include not only the usual logic of contrast or juxtaposition but also a logic of tracing, in order to embrace approaches to comparison that are coherent with critical, constructivist, and interpretive qualitative traditions. Finally, comparative case study researchers consider three axes of comparison : the vertical, which pays attention across levels or scales, from the local through the regional, state, federal, and global; the horizontal, which examines how similar phenomena or policies unfold in distinct locations that are socially produced; and the transversal, which compares over time.

- comparative case studies

- case study research

- comparative case study approach

- epistemology

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Education. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 21 May 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|185.80.150.64]

- 185.80.150.64

Character limit 500 /500

Rethinking case study research: A comparative approach

- Organizational Leadership, Policy and Development

Research output : Book/Report › Book

Comparative case studies are an effective qualitative tool for researching the impact of policy and practice in various fields of social research, including education. Developed in response to the inadequacy of traditional case study approaches, comparative case studies are highly effective because of their ability to synthesize information across time and space. In Rethinking Case Study Research: A Comparative Approach, the authors describe, explain, and illustrate the horizontal, vertical, and transversal axes of comparative case studies in order to help readers develop their own comparative case study research designs. In six concise chapters, two experts employ geographically distinct case studies-from Tanzania to Guatemala to the U.S.-to show how this innovative approach applies to the operation of policy and practice across multiple social fields. With examples and activities from anthropology, development studies, and policy studies, this volume is written for researchers, especially graduate students, in the fields of education and the interpretive social sciences.

Bibliographical note

This output contributes to the following UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

Publisher link

- 10.4324/9781315674889

Other files and links

- Link to publication in Scopus

- Link to the citations in Scopus

Fingerprint

- Comparative Case Study Keyphrases 100%

- Case Study Research Keyphrases 100%

- Case Study Social Sciences 100%

- Research Design Economics, Econometrics and Finance 100%

- Anthropology Keyphrases 25%

- Tanzania Keyphrases 25%

- Innovative Approaches Keyphrases 25%

- Guatemala Keyphrases 25%

T1 - Rethinking case study research

T2 - A comparative approach

AU - Bartlett, Lesley

AU - Vavrus, Frances

N1 - Publisher Copyright: © 2017 Taylor & Francis. All rights reserved.

PY - 2016/11/10

Y1 - 2016/11/10

N2 - Comparative case studies are an effective qualitative tool for researching the impact of policy and practice in various fields of social research, including education. Developed in response to the inadequacy of traditional case study approaches, comparative case studies are highly effective because of their ability to synthesize information across time and space. In Rethinking Case Study Research: A Comparative Approach, the authors describe, explain, and illustrate the horizontal, vertical, and transversal axes of comparative case studies in order to help readers develop their own comparative case study research designs. In six concise chapters, two experts employ geographically distinct case studies-from Tanzania to Guatemala to the U.S.-to show how this innovative approach applies to the operation of policy and practice across multiple social fields. With examples and activities from anthropology, development studies, and policy studies, this volume is written for researchers, especially graduate students, in the fields of education and the interpretive social sciences.

AB - Comparative case studies are an effective qualitative tool for researching the impact of policy and practice in various fields of social research, including education. Developed in response to the inadequacy of traditional case study approaches, comparative case studies are highly effective because of their ability to synthesize information across time and space. In Rethinking Case Study Research: A Comparative Approach, the authors describe, explain, and illustrate the horizontal, vertical, and transversal axes of comparative case studies in order to help readers develop their own comparative case study research designs. In six concise chapters, two experts employ geographically distinct case studies-from Tanzania to Guatemala to the U.S.-to show how this innovative approach applies to the operation of policy and practice across multiple social fields. With examples and activities from anthropology, development studies, and policy studies, this volume is written for researchers, especially graduate students, in the fields of education and the interpretive social sciences.

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?scp=85021003907&partnerID=8YFLogxK

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/citedby.url?scp=85021003907&partnerID=8YFLogxK

U2 - 10.4324/9781315674889

DO - 10.4324/9781315674889

AN - SCOPUS:85021003907

SN - 9781138939516

BT - Rethinking case study research

PB - Taylor and Francis Inc.

This website may not work correctly because your browser is out of date. Please update your browser .

Qualitative comparative analysis

Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) is a means of analysing the causal contribution of different conditions (e.g. aspects of an intervention and the wider context) to an outcome of interest.

QCA starts with the documentation of the different configurations of conditions associated with each case of an observed outcome. These are then subject to a minimisation procedure that identifies the simplest set of conditions that can account for all the observed outcomes, as well as their absence.

The results are typically expressed in statements expressed in ordinary language or as Boolean algebra. For example:

- A combination of Condition A and condition B or a combination of condition C and condition D will lead to outcome E.

- In Boolean notation this is expressed more succinctly as A*B + C*D→E

QCA results are able to distinguish various complex forms of causation, including:

- Configurations of causal conditions, not just single causes. In the example above, there are two different causal configurations, each made up of two conditions.

- Equifinality, where there is more than one way in which an outcome can happen. In the above example, each additional configuration represents a different causal pathway

- Causal conditions which are necessary, sufficient, both or neither, plus more complex combinations (known as INUS causes – insufficient but necessary parts of a configuration that is unnecessary but sufficient), which tend to be more common in everyday life. In the example above, no one condition was sufficient or necessary. But each condition is an INUS type cause

- Asymmetric causes – where the causes of failure may not simply be the absence of the cause of success. In the example above, the configuration associated with the absence of E might have been one like this: A*B*X + C*D*X →e Here X condition was a sufficient and necessary blocking condition.

- The relative influence of different individual conditions and causal configurations in a set of cases being examined. In the example above, the first configuration may have been associated with 10 cases where the outcome was E, whereas the second might have been associated with only 5 cases. Configurations can be evaluated in terms of coverage (the percentage of cases they explain) and consistency (the extent to which a configuration is always associated with a given outcome).

QCA is able to use relatively small and simple data sets. There is no requirement to have enough cases to achieve statistical significance, although ideally there should be enough cases to potentially exhibit all the possible configurations. The latter depends on the number of conditions present. In a 2012 survey of QCA uses the median number of cases was 22 and the median number of conditions was 6. For each case, the presence or absence of a condition is recorded using nominal data i.e. a 1 or 0. More sophisticated forms of QCA allow the use of “fuzzy sets” i.e. where a condition may be partly present or partly absent, represented by a value of 0.8 or 0.2 for example. Or there may be more than one kind of presence, represented by values of 0, 1, 2 or more for example. Data for a QCA analysis is collated in a simple matrix form, where rows = cases and columns = conditions, with the rightmost column listing the associated outcome for each case, also described in binary form.

QCA is a theory-driven approach, in that the choice of conditions being examined needs to be driven by a prior theory about what matters. The list of conditions may also be revised in the light of the results of the QCA analysis if some configurations are still shown as being associated with a mixture of outcomes. The coding of the presence/absence of a condition also requires an explicit view of that condition and when and where it can be considered present. Dichotomisation of quantitative measures about the incidence of a condition also needs to be carried out with an explicit rationale, and not on an arbitrary basis.

Although QCA was originally developed by Charles Ragin some decades ago it is only in the last decade that its use has become more common amongst evaluators. Articles on its use have appeared in Evaluation and the American Journal of Evaluation.

For a worked example, see Charles Ragin’s What is Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA)? , slides 6 to 15 on The bare-bones basics of crisp-set QCA.

[A crude summary of the example is presented here]

In his presentation Ragin provides data on 65 countries and their reactions to austerity measures imposed by the IMF. This has been condensed into a Truth Table (shown below), which shows all possible configurations of four different conditions that were thought to affect countries’ responses: the presence or absence of severe austerity, prior mobilisation, corrupt government, rapid price rises. Next to each configuration is data on the outcome associated with that configuration – the numbers of countries experiencing mass protest or not. There are 16 configurations in all, one per row. The rightmost column describes the consistency of each configuration: whether all cases with that configuration have one type of outcome, or a mixed outcome (i.e. some protests and some no protests). Notice that there are also some configurations with no known cases.

Ragin’s next step is to improve the consistency of the configurations with mixed consistency. This is done either by rejecting cases within an inconsistent configuration because they are outliers (with exceptional circumstances unlikely to be repeated elsewhere) or by introducing an additional condition (column) that distinguishes between those configurations which did lead to protest and those which did not. In this example, a new condition was introduced that removed the inconsistency, which was described as “not having a repressive regime”.

The next step involves reducing the number of configurations needed to explain all the outcomes, known as minimisation. Because this is a time-consuming process, this is done by an automated algorithm (aka a computer program) This algorithm takes two configurations at a time and examines if they have the same outcome. If so, and if their configurations are only different in respect to one condition this is deemed to not be an important causal factor and the two configurations are collapsed into one. This process of comparisons is continued, looking at all configurations, including newly collapsed ones, until no further reductions are possible.

[Jumping a few more specific steps] The final result from the minimisation of the above truth table is this configuration:

SA*(PR + PM*GC*NR)

The expression indicates that IMF protest erupts when severe austerity (SA) is combined with either (1) rapid price increases (PR) or (2) the combination of prior mobilization (PM), government corruption (GC), and non-repressive regime (NR).

This slide show from Charles C Ragin, provides a detailed explanation, including examples, that clearly demonstrates the question, 'What is QCA?'

This book, by Schneider and Wagemann, provides a comprehensive overview of the basic principles of set theory to model causality and applications of Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA), the most developed form of set-theoretic method, for research ac

This article by Nicolas Legewie provides an introduction to Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA). It discusses the method's main principles and advantages, including its concepts.

COMPASSS (Comparative methods for systematic cross-case analysis) is a website that has been designed to develop the use of systematic comparative case analysis as a research strategy by bringing together scholars and practitioners who share its use as

This paper from Patrick A. Mello focuses on reviewing current applications for use in Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) in order to take stock of what is available and highlight best practice in this area.

Marshall, G. (1998). Qualitative comparative analysis. In A Dictionary of Sociology Retrieved from https://www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences/dictionaries-thesauruses-pictures-and-press-releases/qualitative-comparative-analysis

Expand to view all resources related to 'Qualitative comparative analysis'

- An introduction to applied data analysis with qualitative comparative analysis

- Qualitative comparative analysis: A valuable approach to add to the evaluator’s ‘toolbox’? Lessons from recent applications

'Qualitative comparative analysis' is referenced in:

- 52 weeks of BetterEvaluation: Week 34 Generalisations from case studies?

- Week 18: is there a "right" approach to establishing causation in advocacy evaluation?

Framework/Guide

- Rainbow Framework : Check the results are consistent with causal contribution

- Data mining

Back to top

© 2022 BetterEvaluation. All right reserved.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Transl Behav Med

- v.4(2); 2014 Jun

Using qualitative comparative analysis to understand and quantify translation and implementation

Heather kane.

RTI International, 3040 Cornwallis Road, Research Triangle Park, P.O. Box 12194, Durham, NC 27709 USA

Megan A Lewis

Pamela a williams, leila c kahwati.

Understanding the factors that facilitate implementation of behavioral medicine programs into practice can advance translational science. Often, translation or implementation studies use case study methods with small sample sizes. Methodological approaches that systematize findings from these types of studies are needed to improve rigor and advance the field. Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) is a method and analytical approach that can advance implementation science. QCA offers an approach for rigorously conducting translational and implementation research limited by a small number of cases. We describe the methodological and analytic approach for using QCA and provide examples of its use in the health and health services literature. QCA brings together qualitative or quantitative data derived from cases to identify necessary and sufficient conditions for an outcome. QCA offers advantages for researchers interested in analyzing complex programs and for practitioners interested in developing programs that achieve successful health outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

In this paper, we describe the methodological features and advantages of using qualitative comparative analysis (QCA). QCA is sometimes called a “mixed method.” It refers to both a specific research approach and an analytic technique that is distinct from and offers several advantages over traditional qualitative and quantitative methods [ 1 – 4 ]. It can be used to (1) analyze small to medium numbers of cases (e.g., 10 to 50) when traditional statistical methods are not possible, (2) examine complex combinations of explanatory factors associated with translation or implementation “success,” and (3) combine qualitative and quantitative data using a unified and systematic analytic approach.

This method may be especially pertinent for behavioral medicine given the growing interest in implementation science [ 5 ]. Translating behavioral medicine research and interventions into useful practice and policy requires an understanding of the implementation context. Understanding the context under which interventions work and how different ways of implementing an intervention lead to successful outcomes are required for “T3” (i.e., dissemination and implementation of evidence-based interventions) and “T4” translations (i.e., policy development to encourage evidence-based intervention use among various stakeholders) [ 6 , 7 ].

Case studies are a common way to assess different program implementation approaches and to examine complex systems (e.g., health care delivery systems, interventions in community settings) [ 8 ]. However, multiple case studies often have small, naturally limited samples or populations; small samples and populations lack adequate power to support conventional, statistical analyses. Case studies also may use mixed-method approaches, but typically when researchers collect quantitative and qualitative data in tandem, they rarely integrate both types of data systematically in the analysis. QCA offers solutions for the challenges posed by case studies and provides a useful analytic tool for translating research into policy recommendations. Using QCA methods could aid behavioral medicine researchers who seek to translate research from randomized controlled trials into practice settings to understand implementation. In this paper, we describe the conceptual basis of QCA, its application in the health and health services literature, and its features and limitations.

CONCEPTUAL BASIS OF QCA

QCA has its foundations in historical, comparative social science. Researchers in this field developed QCA because probabilistic methods failed to capture the complexity of social phenomena and required large sample sizes [ 1 ]. Recently, this method has made inroads into health research and evaluation [ 9 – 13 ] because of several useful features as follows: (1) it models equifinality , which is the ability to identify more than one causal pathway to an outcome (or absence of the outcome); (2) it identifies conjunctural causation , which means that single conditions may not display their effects on their own, but only in conjunction with other conditions; and (3) it implies asymmetrical relationships between causal conditions and outcomes, which means that causal pathways for achieving the outcome differ from causal pathways for failing to achieve the outcome.

QCA is a case-oriented approach that examines relationships between conditions (similar to explanatory variables in regression models) and an outcome using set theory; a branch of mathematics or of symbolic logic that deals with the nature and relations of sets. A set-theoretic approach to modeling causality differs from probabilistic methods, which examines the independent, additive influence of variables on an outcome. Regression models, based on underlying assumptions about sampling and distribution of the data, ask “what factor, holding all other factors constant at each factor’s average, will increase (or decrease) the likelihood of an outcome .” QCA, an approach based on the examination of set, subset, and superset relationships, asks “ what conditions —alone or in combination with other conditions—are necessary or sufficient to produce an outcome .” For additional QCA definitions, see Ragin [ 4 ].

Necessary conditions are those that exhibit a superset relationship with the outcome set and are conditions or combinations of conditions that must be present for an outcome to occur. In assessing necessity, a researcher “identifies conditions shared by cases with the same outcome” [ 4 ] (p. 20). Figure 1 shows a hypothetical example. In this figure, condition X is a necessary condition for an effective intervention because all cases with condition X are also members of the set of cases with the outcome present; however, condition X is not sufficient for an effective intervention because it is possible to be a member of the set of cases with condition X, but not be a member of the outcome set [ 14 ].

Necessary and sufficient conditions and set-theoretic relationships

Sufficient conditions exhibit subset relationships with an outcome set and demonstrate that “the cause in question produces the outcome in question” [ 3 ] (p. 92). Figure 1 shows the multiple and different combinations of conditions that produce the hypothetical outcome, “effective intervention,” (1) by having condition A present, (2) by having condition D present, or (3) by having the combination of conditions B and C present. None of these conditions is necessary and any one of these conditions or combinations of conditions is sufficient for the outcome of an effective intervention.

QCA AS AN APPROACH AND AS AN ANALYTIC TECHNIQUE

The term “QCA” is sometimes used to refer to the comparative research approach but also refers to the “analytic moment” during which Boolean algebra and set theory logic is applied to truth tables constructed from data derived from included cases. Figure 2 characterizes this distinction. Although this figure depicts steps as sequential, like many research endeavors, these steps are somewhat iterative, with respecification and reanalysis occurring along the way to final findings. We describe each of the essential steps of QCA as an approach and analytic technique and provide examples of how it has been used in health-related research.

QCA as an approach and as an analytic technique

Operationalizing the research question

Like other types of studies, the first step involves identifying the research question(s) and developing a conceptual model. This step guides the study as a whole and also informs case, condition (c.f., variable), and outcome selection. As mentioned above, QCA frames research questions differently than traditional quantitative or qualitative methods. Research questions appropriate for a QCA approach would seek to identify the necessary and sufficient conditions required to achieve the outcome. Thus, formulating a QCA research question emphasizes what program components or features—individually or in combination—need to be in place for a program or intervention to have a chance at being effective (i.e., necessary conditions) and what program components or features—individually or in combination—would produce the outcome (i.e., sufficient conditions). For example, a set theoretic hypothesis would be as follows: If a program is supported by strong organizational capacity and a comprehensive planning process, then the program will be successful. A hypothesis better addressed by probabilistic methods would be as follows: Organizational capacity, holding all other factors constant, increases the likelihood that a program will be successful.

For example, Longest and Thoits [ 15 ] drew on an extant stress process model to assess whether the pathways leading to psychological distress differed for women and men. Using QCA was appropriate for their study because the stress process model “suggests that particular patterns of predictors experienced in tandem may have unique relationships with health outcomes” (p. 4, italics added). They theorized that predictors would exhibit effects in combination because some aspects of the stress process model would buffer the risk of distress (e.g., social support) while others simultaneously would increase the risk (e.g., negative life events).

Identify cases

The number of cases in a QCA analysis may be determined by the population (e.g., 10 intervention sites, 30 grantees). When particular cases can be chosen from a larger population, Berg-Schlosser and De Meur [ 16 ] offer other strategies and best practices for choosing cases. Unless the number of cases relies on an existing population (i.e., 30 programs or grantees), the outcome of interest and existing theory drive case selection, unlike variable-oriented research [ 3 , 4 ] in which numbers are driven by statistical power considerations and depend on variation in the dependent variable. For use in causal inference, both cases that exhibit and do not exhibit the outcome should be included [ 16 ]. If a researcher is interested in developing typologies or concept formation, he or she may wish to examine similar cases that exhibit differences on the outcome or to explore cases that exhibit the same outcome [ 14 , 16 ].

For example, Kahwati et al. [ 9 ] examined the structure, policies, and processes that might lead to an effective clinical weight management program in a large national integrated health care system, as measured by mean weight loss among patients treated at the facility. To examine pathways that lead to both better and poorer facility-level weight loss, 11 facilities from among those with the largest weight loss outcomes and 11 facilities from among those with the smallest were included. By choosing cases based on specific outcomes, Kahwati et al. could identify multiple patterns of success (or failure) that explain the outcome rather than the variability associated with the outcome.

Identify conditions and outcome sets

Selecting conditions relies on the research question, conceptual model, and number of cases similar to other research methods. Conditions (or “sets” or “condition sets”) refer to the explanatory factors in a model; they are similar to variables. Because QCA research questions assess necessary and sufficient conditions, a researcher should consider which conditions in the conceptual model would theoretically produce the outcome individually or in combination. This helps to focus the analysis and number of conditions. Ideally, for a case study design with a small (e.g., 10–15) or intermediate (e.g., 16–100) number of cases, one should aim for fewer than five conditions because in QCA a researcher assesses all possible configurations of conditions. Adding conditions to the model increases the possible number of combinations exponentially (i.e., 2 k , where k = the number of conditions). For three conditions, eight possible combinations of the selected conditions exist as follows: the presence of A, B, C together, the lack of A with B and C present, the lack of A and lack of B with C present, and so forth. Having too many conditions will likely mean that no cases fall into a particular configuration, and that configuration cannot be assessed by empirical examples. When one or more configurations are not represented by the cases, this is known as limited diversity, and QCA experts suggest multiple strategies for managing such situations [ 4 , 14 ].

For example, Ford et al. [ 10 ] studied health departments’ implementation of core public health functions and organizational factors (e.g., resource availability, adaptability) and how those conditions lead to superior and inferior population health changes. They operationalized three core public functions (i.e., assessment of environmental and population public health needs, capacity for policy development, and authority over assurance of healthcare operations) and operationalized those for their study by using composite measures of varied health indicators compiled in a UnitedHealth Group report. In this examination of 41 state health departments, the authors found that all three core public health functions were necessary for population health improvement. The absence of any of the core public health functions was sufficient for poorer population health outcomes; thus, only the health departments with the ability to perform all three core functions had improved outcomes. Additionally, these three core functions in combination with either resource availability or adaptability were sufficient combinations (i.e., causal pathways) for improved population health outcomes.

Calibrate condition and outcome sets

Calibration refers to “adjusting (measures) so that they match or conform to dependably known standards” and is a common way of standardizing data in the physical sciences [ 4 ] (p. 72). Calibration requires the researcher to make sense of variation in the data and apply expert knowledge about what aspects of the variation are meaningful. Because calibration depends on defining conditions based on those “dependably known standards,” QCA relies on expert substantive knowledge, theory, or criteria external to the data themselves [ 14 ]. This may require researchers to collaborate closely with program implementers.

In QCA, one can use “crisp” set or “fuzzy” set calibration. Crisp sets, which are similar to dichotomous categorical variables in regression, establish decision rules defining a case as fully in the set (i.e., condition) or fully out of the set; fuzzy sets establish degrees of membership in a set. Fuzzy sets “differentiate between different levels of belonging anchored by two extreme membership scores at 1 and 0” [ 14 ] (p.28). They can be continuous (0, 0.1, 0.2,..) or have qualitatively defined anchor points (e.g., 0 is fully out of the set; 0.33 is more out than in the set; 0.66 is more in than out of the set; 1 is fully in the set). A researcher selects fuzzy sets and the corresponding resolution (i.e., continuous, four cutoff points, six cutoff) based on theory and meaningful differences between cases and must be able to provide a verbal description for each cutoff point [ 14 ]. If, for example, a researcher cannot distinguish between 0.7 and 0.8 membership in a set, then a more continuous scoring of cases would not be useful, rather a four point cutoff may better characterize the data. Although crisp and fuzzy sets are more commonly used, new multivariate forms of QCA are emerging as are variants that incorporate elements of time [ 14 , 17 , 18 ].

Fuzzy sets have the advantage of maintaining more detail for data with continuous values. However, this strength also makes interpretation more difficult. When an observation is coded with fuzzy sets, a particular observation has some degree of membership in the set “condition A” and in the set “condition NOT A.” Thus, when doing analyses to identify sufficient conditions, a researcher must make a judgment call on what benchmark constitutes recommendation threshold for policy or programmatic action.

In creating decision rules for calibration, a researcher can use a variety of techniques to identify cutoff points or anchors. For qualitative conditions, a researcher can define decision rules by drawing from the literature and knowledge of the intervention context. For conditions with numeric values, a researcher can also employ statistical approaches. Ideally, when using statistical approaches, a researcher should establish thresholds using substantive knowledge about set membership (thus, translating variation into meaningful categories). Although measures of central tendency (e.g., cases with a value above the median are considered fully in the set) can be used to set cutoff points, some experts consider the sole use of this method to be flawed because case classification is determined by a case’s relative value in regard to other cases as opposed to its absolute value in reference to an external referent [ 14 ].

For example, in their study of National Cancer Institutes’ Community Clinical Oncology Program (NCI CCOP), Weiner et al. [ 19 ] had numeric data on their five study measures. They transformed their study measures by using their knowledge of the CCOP and by asking NCI officials to identify three values: full membership in a set, a point of maximum ambiguity, and nonmembership in the set. For their outcome set, high accrual in clinical trials, they established 100 patients enrolled accrual as fully in the set of high accrual, 70 as a point of ambiguity (neither in nor out of the set), and 50 and below as fully out of the set because “CCOPs must maintain a minimum of 50 patients to maintain CCOP funding” (p. 288). By using QCA and operationalizing condition sets in this way, they were able to answer what condition sets produce high accrual, not what factors predict more accrual. The advantage is that by using this approach and analytic technique, they were able to identify sets of factors that are linked with a very specific outcome of interest.

Obtain primary or secondary data

Data sources vary based on the study, availability of the data, and feasibility of data collection; data can be qualitative or quantitative, a feature useful for mixed-methods studies and systematically integrating these different types of data is a major strength of this approach. Qualitative data include program documents and descriptions, key informant interviews, and archival data (e.g., program documents, records, policies); quantitative data consists of surveys, surveillance or registry data, and electronic health records.

For instance, Schensul et al. [ 20 ] relied on in-depth interviews for their analysis; Chuang et al. [ 21 ] and Longest and Thoits [ 15 ] drew on survey data for theirs. Kahwati et al. [ 9 ] used a mixed-method approach combining data from key informant interviews, program documents, and electronic health records. Any type of data can be used to inform the calibration of conditions.

Assign set membership scores

Assigning set membership scores involves applying the decision rules that were established during the calibration phase. To accomplish this, the research team should then use the extracted data for each case, apply the decision rule for the condition, and discuss discrepancies in the data sources. In their study of factors that influence health care policy development in Florida, Harkreader and Imershein [ 22 ] coded contextual factors that supported state involvement in the health care market. Drawing on a review of archival data and using crisp set coding, they assigned a value of 1 for the presence of a contextual factor (e.g., presence of federal financial incentives promoting policy, unified health care provider policy position in opposition to state policy, state agency supporting policy position) and 0 for the absence of a contextual factor.

Construct truth table

After completing the coding, researchers create a “truth table” for analysis. A truth table lists all of the possible configurations of conditions, the number of cases that fall into that configuration, and the “consistency” of the cases. Consistency quantifies the extent to which cases that share similar conditions exhibit the same outcome; in crisp sets, the consistency value is the proportion of cases that exhibit the outcome. Fuzzy sets require a different calculation to establish consistency and are described at length in other sources [ 1 – 4 , 14 ]. Table 1 displays a hypothetical truth table for three conditions using crisp sets.

Sample of a hypothetical truth table for crisp sets

1 fully in the set, 0 fully out of the set

QCA AS AN ANALYTIC TECHNIQUE

The research steps to this point fall into QCA as an approach to understanding social and health phenomena. Analysis of the truth table is the sine qua non of QCA as an analytic technique. In this section, we provide an overview of the analysis process, but analytic techniques and emerging forms of analysis are described in multiple texts [ 3 , 4 , 14 , 17 ]. The use of computer software to conduct truth table analysis is recommended and several software options are available including Stata, fsQCA, Tosmana, and R.

A truth table analysis first involves the researcher assessing which (if any) conditions are individually necessary or sufficient for achieving the outcome, and then second, examining whether any configurations of conditions are necessary or sufficient. In instances where contradictions in outcomes from the same configuration pattern occur (i.e., one case from a configuration has the outcome; one does not), the researcher should also consider whether the model is properly specified and conditions are calibrated accurately. Thus, this stage of the analysis may reveal the need to review how conditions are defined and whether the definition should be recalibrated. Similar to qualitative and quantitative research approaches, analysis is iterative.

Additionally, the researcher examines the truth table to assess whether all logically possible configurations have empiric cases. As described above, when configurations lack cases, the problem of limited diversity occurs. Configurations without representative cases are known as logical remainders, and the researcher must consider how to deal with those. The analysis of logical remainders depends on the particular theory guiding the research and the research priorities. How a researcher manages the logical remainders has implications for the final solution, but none of the solutions based on the truth table will contradict the empirical evidence [ 14 ]. To generate the most conservative solution term, a researcher makes no assumptions about truth table rows with no cases (or very few cases in larger N studies) and excludes them from the logical minimization process. Alternately, a researcher can choose to include (or exclude) rows with no cases from analysis, which would generate a solution that is a superset of the conservative solution. Choosing inclusion criteria for logical remainders also depends on theory and what may be empirically possible. For example, in studying governments, it would be unlikely to have a case that is a democracy (“condition A”), but has a dictator (“condition B”). In that circumstance, the researcher may choose to exclude that theoretically implausible row from the logical minimization process.

Third, once all the solutions have been identified, the researcher mathematically reduces the solution [ 1 , 14 ]. For example, if the list of solutions contains two identical configurations, except that in one configuration A is absent and in the other A is present, then A can be dropped from those two solutions. Finally, the researcher computes two parameters of fit: coverage and consistency. Coverage determines the empirical relevance of a solution and quantifies the variation in causal pathways to an outcome [ 14 ]. When coverage of a causal pathway is high, the more common the solution is, and more of the outcome is accounted for by the pathway. However, maximum coverage may be less critical in implementation research because understanding all of the pathways to success may be as helpful as understanding the most common pathway. Consistency assesses whether the causal pathway produces the outcome regularly (“the degree to which the empirical data are in line with a postulated subset relation,” p. 324 [ 14 ]); a high consistency value (e.g., 1.00 or 100 %) would indicate that all cases in a causal pathway produced the outcome. A low consistency value would suggest that a particular pathway was not successful in producing the outcome on a regular basis, and thus, for translational purposes, should not be recommended for policy or practice changes. A causal pathway with high consistency and coverage values indicates a result useful for providing guidance; a high consistency with a lower coverage score also has value in showing a causal pathway that successfully produced the outcome, but did so less frequently.

For example, Kahwati et al. [ 9 ] examined their truth table and analyzed the data for single conditions and combinations of conditions that were necessary for higher or lower facility-level patient weight loss outcomes. The truth table analysis revealed two necessary conditions and four sufficient combinations of conditions. Because of significant challenges with logical remainders, they used a bottom-up approach to assess whether combinations of conditions yielded the outcome. This entailed pairing conditions to ensure parsimony and maximize coverage. With a smaller number of conditions, a researcher could hypothetically find that more cases share similar characteristics and could assess whether those cases exhibit the same outcome of interest.

At the completion of the truth table analysis, Kahwati et al. [ 9 ] used the qualitative data from site interviews to provide rich examples to illustrate the QCA solutions that were identified, which explained what the solutions meant in clinical practice for weight management. For example, having an involved champion (usually a physician), in combination with low facility accountability, was sufficient for program success (i.e., better weight loss outcomes) and was related to better facility weight loss. In reviewing the qualitative data, Kahwati et al. [ 9 ] discovered that involved champions integrate program activities into their clinical routines and discuss issues as they arise with other program staff. Because involved champions and other program staff communicated informally on a regular basis, formal accountability structures were less of a priority.

ADVANTAGES AND LIMITATIONS OF QCA

Because translational (and other health-related) researchers may be interested in which intervention features—alone or in combination—achieve distinct outcomes (e.g., achievement of program outcomes, reduction in health disparities), QCA is well suited for translational research. To assess combinations of variables in regression, a researcher relies on interaction effects, which, although useful, become difficult to interpret when three, four, or more variables are combined. Furthermore, in regression and other variable-oriented approaches, independent variables are held constant at the average across the study population to isolate the independent effect of that variable, but this masks how factors may interact with each other in ways that impact the ultimate outcomes. In translational research, context matters and QCA treats each case holistically, allowing each case to keep its own values for each condition.

Multiple case studies or studies with the organization as the unit of analysis often involve a small or intermediate number of cases. This hinders the use of standard statistical analyses; researchers are less likely to find statistical significance with small sample sizes. However, QCA draws on analyses of set relations to support small-N studies and to identify the conditions or combinations of conditions that are necessary or sufficient for an outcome of interest and may yield results when probabilistic methods cannot.

Finally, QCA is based on an asymmetric concept of causation , which means that the absence of a sufficient condition associated with an outcome does not necessarily describe the causal pathway to the absence of the outcome [ 14 ]. These characteristics can be helpful for translational researchers who are trying to study or implement complex interventions, where more than one way to implement a program might be effective and where studying both effective and ineffective implementation practices can yield useful information.

QCA has several limitations that researchers should consider before choosing it as a potential methodological approach. With small- and intermediate-N studies, QCA must be theory-driven and circumscribed by priority questions. That is, a researcher ideally should not use a “kitchen sink” approach to test every conceivable condition or combination of conditions because the number of combinations increases exponentially with the addition of another condition. With a small number of cases and too many conditions, the sample would not have enough cases to provide examples of all the possible configurations of conditions (i.e., limited diversity), or the analysis would be constrained to describing the characteristics of the cases, which would have less value than determining whether some conditions or some combination of conditions led to actual program success. However, if the number of conditions cannot be reduced, alternate QCA techniques, such as a bottom-up approach to QCA or two-step QCA, can be used [ 14 ].

Another limitation is that programs or clinical interventions involved in a cross-site analysis may have unique programs that do not seem comparable. Cases must share some degree of comparability to use QCA [ 16 ]. Researchers can manage this challenge by taking a broader view of the program(s) and comparing them on broader characteristics or concepts, such as high/low organizational capacity, established partnerships, and program planning, if these would provide meaningful conclusions. Taking this approach will require careful definition of each of these concepts within the context of a particular initiative. Definitions may also need to be revised as the data are gathered and calibration begins.

Finally, as mentioned above, crisp set calibration dichotomizes conditions of interest; this form of calibration means that in some cases, the finer grained differences and precision in a condition may be lost [ 3 ]. Crisp set calibration provides more easily interpretable and actionable results and is appropriate if researchers are primarily interested in the presence or absence of a particular program feature or organizational characteristic to understand translation or implementation.

QCA offers an additional methodological approach for researchers to conduct rigorous comparative analyses while drawing on the rich, detailed data collected as part of a case study. However, as Rihoux, Benoit, and Ragin [ 17 ] note, QCA is not a miracle method, nor a panacea for all studies that use case study methods. Furthermore, it may not always be the most suitable approach for certain types of translational and implementation research. We outlined the multiple steps needed to conduct a comprehensive QCA. QCA is a good approach for the examination of causal complexity, and equifinality could be helpful to behavioral medicine researchers who seek to translate evidence-based interventions in real-world settings. In reality, multiple program models can lead to success, and this method accommodates a more complex and varied understanding of these patterns and factors.

Implications

Practice : Identifying multiple successful intervention models (equifinality) can aid in selecting a practice model relevant to a context, and can facilitate implementation.

Policy : QCA can be used to develop actionable policy information for decision makers that accommodates contextual factors.

Research : Researchers can use QCA to understand causal complexity in translational or implementation research and to assess the relationships between policies, interventions, or procedures and successful outcomes.

The “qualitative” in qualitative comparative analysis (QCA): research moves, case-intimacy and face-to-face interviews

- Open access

- Published: 26 March 2022

- Volume 57 , pages 489–507, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Sofia Pagliarin ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4846-6072 3 , 4 ,

- Salvatore La Mendola 2 &

- Barbara Vis 1

8818 Accesses

5 Citations

5 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) includes two main components: QCA “as a research approach” and QCA “as a method”. In this study, we focus on the former and, by means of the “interpretive spiral”, we critically look at the research process of QCA. We show how QCA as a research approach is composed of (1) an “analytical move”, where cases, conditions and outcome(s) are conceptualised in terms of sets, and (2) a “membership move”, where set membership values are qualitatively assigned by the researcher (i.e. calibration). Moreover, we show that QCA scholars have not sufficiently acknowledged the data generation process as a constituent research phase (or “move”) for the performance of QCA. This is particularly relevant when qualitative data–e.g. interviews, focus groups, documents–are used for subsequent analysis and calibration (i.e. analytical and membership moves). We call the qualitative data collection process “relational move” because, for data gathering, researchers establish the social relation “interview” with the study participants. By using examples from our own research, we show how a dialogical interviewing style can help researchers gain the in-depth knowledge necessary to meaningfully represent qualitative data into set membership values for QCA, hence improving our ability to account for the “qualitative” in QCA.

Similar content being viewed by others

The role of analytic direction in qualitative research

Adapting and blending grounded theory with case study: a practical guide

Working at a remove: continuous, collective, and configurative approaches to qualitative secondary analysis.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) is a configurational comparative research approach and method for the social sciences based on set-theory. It was introduced in crisp-set form by Ragin ( 1987 ) and later expanded to fuzzy sets (Ragin 2000 ; 2008a ; Rihoux and Ragin 2009 ; Schneider and Wagemann 2012 ). QCA is a diversity-oriented approach extending “the single-case study to multiple cases with an eye toward configurations of similarities and differences” (Ragin 2000 :22). QCA aims at finding a balance between complexity and generalizability by identifying data patterns that can exhibit or approach set-theoretic connections (Ragin 2014 :88).

As a research approach, QCA researchers first conceptualise cases as elements belonging, in kind and/or degree, to a selection of conditions and outcome(s) that are conceived as sets. They then assign cases’ set membership values to conditions and outcome(s) (i.e. calibration). Populations are constructed for outcome-oriented investigations and causation is conceived to be conjunctural and heterogeneous (Ragin 2000 : 39ff). As a method, QCA is the systematic and formalised analysis of the calibrated dataset for cross-case comparison through Boolean algebra operations. Combinations of conditions (i.e. configurations) represent both the characterising features of cases and also the multiple paths towards the outcome (Byrne 2005 ).

Most of the critiques to QCA focus on the methodological aspects of “QCA as a method” (e.g. Lucas and Szatrowski 2014 ), although epistemological issues regarding deterministic causality and subjectivity in assigning set membership values are also discussed (e.g. Collier 2014 ). In response to these critiques, Ragin ( 2014 ; see also Ragin 2000 , ch. 11) emphasises the “mindset shift” needed to perform QCA: QCA “as a method” makes sense only if researchers admit “QCA as a research approach”, including its qualitative component.

The qualitative character of QCA emerges when recognising the relevance of case-based knowledge or “case intimacy”. The latter is key to perform calibration (see e.g. Ragin 2000 :53–61; Byrne 2005 ; Ragin 2008a ; Harvey 2009 ; Greckhamer et al. 2013 ; Gerrits and Verweij 2018 :36ff): when associating “meanings” to “numbers”, researchers engage in a “dialogue between ideas and evidence” by using set-membership values as “ interpretive tools ” (Ragin 2000 : 162, original emphasis). The foundations of QCA as a research approach are explicitly rooted in qualitative, case-oriented research approaches in the social sciences, in particular in the understanding of causation as multiple and configurational, in terms of combinations of conditions, and in the conceptualisation of populations as types of cases, which should be refined in the course of an investigation (Ragin 2000 : 30–42).

Arguably, QCA researchers should make ample use of qualitative methods for the social sciences, such as narrative or semi-structured interviews, focus groups, discourse and document analysis, because this will help gain case intimacy and enable the dialogue between theories and data. Furthermore, as many QCA-studies have a small to medium sample size (10–50 cases), qualitative data collection methods appear to be particularly appropriate to reach both goals. However, so far only around 30 published QCA studies use qualitative data (de Block and Vis 2018 ), out of which only a handful employ narrative interviews (see Sect. 2 ).

We argue that this puzzling observation about QCA empirical research is due to two main reasons. First, quantitative data, in particular secondary data available from official databases, are more malleable for calibration. Although QCA researchers should carefully distinguish between measurement and calibration (see e.g. Ragin, 2008a , b ; Schneider and Wagemann 2012 , Sect. 1.2), quantitative data are more convenient for establishing the three main qualitative anchors (i.e. the cross-over point as maximum ambiguity; the lower and upper thresholds for full set membership exclusion or inclusion). Quantitative data facilitate QCA researchers in performing QCA both as a research approach and method. QCA scholars are somewhat aware of this when discussing “the two QCAs” (large-n/quantitative data and small-n/more frequent use of qualitative data; Greckhamer et al. 2013 ; see also Thomann and Maggetti 2017 ).

Second, the use of qualitative data for performing QCA requires an additional effort from the part of the researcher, because data collected through, for instance, narrative interviews, focus groups and document analysis come in verbal form. Therefore, QCA researchers using qualitative methods for empirical research have to first collect data and only then move to their analysis and conceptualisation as sets (analytical move) and their calibration into “numbers” (membership move) for their subsequent handling through QCA procedures (QCA as a method).

Because of these two main reasons, we claim that data generation (or data construction) should also be recognised and integrated in the QCA research process. Fully accounting for QCA as a “qualitative” research approach necessarily entails questions about the data generation process, especially when qualitative research methods are used that come in verbal, and not numerical, form.

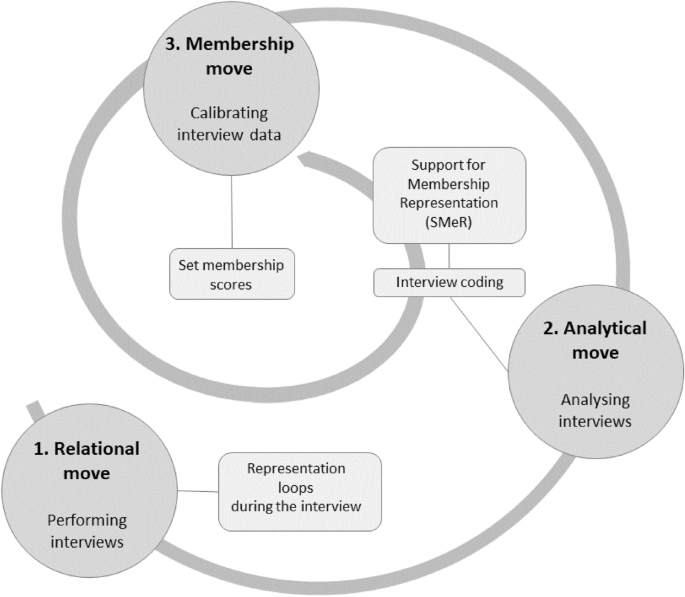

This study’s contributions are twofold. First, we present the “interpretative spiral” (see Fig. 1 ) or “cycle” (Sandelowski et al. 2009 ) where data gradually transit through changes of state: from meanings, to concepts to numerical values. In limiting our discussion to QCA as a research approach, we identified three main moves composing the interpretative spiral: the (1) relational (data generation through qualitative methods), (2) analytical (set conceptualisation) and (3) membership (calibration) moves. Second, we show how in-depth knowledge for subsequent set conceptualisation and calibration can be more effectively generated if the researcher is open, during data collection, to support the interviewee’s narration and to establish a dialogue—a relation—with him/her (i.e. the relational move). It is the researcher’s openness that can facilitate the development of case intimacy for set conceptualisation and assessment (analytical and membership moves). We hence introduce a “dialogical” interviewing style (La Mendola 2009 ) to show how this approach can be useful for QCA researchers. Although we mainly discuss narrative interviews, a dialogical interviewing style can also adapt to face-to-face semi-structured interviews or questionnaires.

The interpretative spiral and the relational, analytical and membership moves

Our main aim is to make QCA researchers more aware of “minding their moves” in the interpretative spiral. Additionally, we show how a “dialogical” interviewing style can facilitate the access to the in-depth knowledge of cases useful for calibration. Researchers using narrative interviews who have not yet performed QCA can gain insight into–and potentially see the advantages of–how qualitative data, in particular narrative interviews, can be employed for the performance of QCA (see Gerrits and Verweij 2018 :36ff).

In Sect. 2 we present the interpretative spiral (Fig. 1 ,) the interconnections between the three moves and we discuss the limited use of qualitative data in QCA research. In Sect. 3 , we examine the use of qualitative data for performing QCA by discussing the relational move and a dialogical interviewing style. In Sect. 4 , we examine the analytical and membership moves and discuss how QCA researchers have so far dealt with them when using qualitative data. In Sect. 5 , we conclude by putting forward some final remarks.

2 The interpretative spiral and the three moves

Sandelowski et al. ( 2009 ) state that the conversion of qualitative data into quantitative data (“quantitizing”) necessarily involves “qualitazing”, because researchers perform a “continuous cycling between assigning numbers to meaning and meaning to numbers” (p. 213). “Data” are recognised as “the product of a move on the part of researchers” (p. 209, emphasis added) because information has to be conceptualised, understood and interpreted to become “data”. In Fig. 1 , we tailor this “cycling” to the performance of QCA by means of the interpretative spiral.

Through the interpretative spiral, we show both how knowledge for QCA is transformed into data by means of “moves” and how the gathering of qualitative data consists of a move on its own. Our choice for the term “move” is grounded in the need to communicate a sense of movement along the “cycling” between meanings and numbers. Furthermore, the term “move” resonates with the communicative steps that interviewers and interviewee engage in during an interview (see Sect. 3 below).

Although we present these moves as separate, they are in reality interfaces, because they are part of the same interpretative spiral. They can be thought of as moves in a dance; the latter emerges because of the succession of moves and steps as a whole, as we show below.

The analytical and membership moves are intertwined-as shown by the central “vortex” of the spiral in Fig. 1 -as they are composed of a number of interrelated steps, in particular case selection, theory-led set conceptualisation, definition of the most appropriate set membership scales and of the cross-over and upper and lower thresholds (e.g. crisp-set, 4- or 6-scale fuzzy-sets; see Ragin 2000 :166–171; Rihoux and Ragin 2009 ). Calibration is the last move of the dialogue between theory (concepts of the analytical move) and data (cases). In the membership move, fuzzy sets are used as “an interpretative algebra, a language that is half-verbal-conceptual and half-mathematical-analytical” (Ragin 2000 :4). Calibration is hence a type of “quantitizing” and “qualitizing” (Sandelowski et al. 2009 ). In applied QCA, set membership values can be reconceptualised and recalibrated. This will for instance be done to solve true logical contradictions in the truth table and when QCA results are interpreted by “going back to cases”, hence overlapping with the practices related to QCA “as a method”.

The relational move displayed in Fig. 1 expresses the additional interpretative process that researchers engage in when collecting and analysing qualitative data. De Block and Vis ( 2018 ) show that only around 30 published QCA-studies combine qualitative data with QCA, including a range of additional data, like observations, site visits, newspaper articles.

However, a closer look reveals that the majority of the published QCA-studies using qualitative data employ (semi)structured interviews or questionnaires. Footnote 1 For instance, Basurto and Speer ( 2012 ) Footnote 2 proposed a step-wise calibration process based on a frequency-oriented strategy (e.g. number of meetings, amount of available information) to calibrate the information collected through 99 semi-structured interviews. Fischer ( 2015 ) conducted 250 semi-structured interviews by cooperating with four trained researchers using pre-structured questions, where respondents could voluntarily add “qualitative pieces of information” in “an interview protocol” (p. 250). Henik ( 2015 ) structured and carried out 50 interviews on whistle-blowing episodes to ensure subsequent blind coding of a high number of items (almost 1000), arguably making them resemble face-to-face questionnaires.

In turn, only a few QCA-researchers use data from narrative interviews. Footnote 3 For example, Metelits ( 2009 ) conducted narrative interviews during ethnographic fieldwork over the course of several years. Verweij and Gerrits ( 2015 ) carried out 18 “open” interviews, while Chai and Schoon ( 2016 ) conducted “in-depth” interviews. Wang ( 2016 ), in turn, conducted structured interviews through a questionnaire, following a similar approach as in Fischer ( 2015 ); however, during the interviews, Wang’s respondents were asked to reflexively justify the chosen questionnaire's responses, hence moving the structured interviews closer to narrative ones. Tóth et al. ( 2017 ) performed 28 semi-structured interviews with company managers to evaluate the quality and attractiveness of customer-provider relationships for maintaining future business relations. Their empirical strategy was however grounded in initial focus groups and other semi-structured interviews, composed of open questions in the first part and a questionnaire in the second part (Tóth et al. 2015 ).

Although no interview is completely structured or unstructured, it is useful to conceptualise (semi-)structured and less structured (or narrative) interviews as the two ends of a continuum (Brinkmann 2014 ). Albeit still relatively rare as compared to quantitative data, the more popular integration of (semi-)structured interviews into QCA might be due to the advantages that this type of qualitative data holds for calibration. The “structured” portion of face-to-face semi-structured interviews or questionnaires facilitates the calibration of this type of qualitative data, because quantitative anchor points can be more clearly identified to assign set membership values (see e.g. Basurto and Speer 2012 ; Fischer 2015 ; Henik 2015 ).

Hence, when critically looking at the “qualitative” character of QCA as a research approach, applied research shows that qualitative methods uneasily fit with QCA. This is because data collection has not been recognised as an integral part of the QCA research process. In Sect. 3 , we show how qualitative data, and in particular a dialogical interviewing style, can help researchers to develop case intimacy.

3 The relational move

Social data are not self-evident facts, they do not reveal anything in themselves, but researchers must engage in interpretative efforts concerning their meaning (Sandelowski et al. 2009 ; Silverman, 2017 ). Differently stated, quantitising and qualitising characterise both quantitative and qualitative social data, albeit to different degrees (Sandelowski et al. 2009 ). This is an ontological understanding of reality that is diversely held by post-positivist, critical realist, critical and constructivist approaches (except by positivist scholars; see Guba and Lincoln, 2005 :193ff). Our position is more akin to critical realism that, in contrast to post-modernist perspectives (Spencer et al. 2014 :85ff), holds that reality exists “out there” and that epistemologically, our knowledge of it, although imperfect, is possible–for instance through the scientific method (Sayer 1992 ).

The socially constructed, not self-evident character of social data is manifest in the collection and analysis of qualitative data. Access to the field needs to be earned, as well as trust and consent from participants, to gradually build and expand a network of participants. More than “collected”, data are “gathered”, because they imply the cooperation with participants. Data from interviews and observations are heterogeneous, and need to be transcribed and analysed by researchers, who also self-reflectively experience the entire process of data collection. QCA researchers using qualitative data necessarily have to go through this additional research process–or move-to gather and generate data, before QCA as a research approach can even start. As QCA researchers using qualitative data need to interact with participants to collect their data, we call this additional research process “relational move”.

While we limit our discussion to narrative interviews and select a few references from a vast literature, our claim is that it is the ability of the interviewer to give life to interviews as a distinct type of social interaction that is key for the data collection process (Chase 2005 ; Leech 2002 ; La Mendola 2009 ; Brinkmann. 2014 ). The ability of the interviewer to establish a dialogue with the interviewee–also in the case of (semi-)structured interviews–is crucial to gain access to case-based knowledge and thus develop the case intimacy later needed in the analytical and membership moves. The relational move is about a researcher’s ability to handle the intrinsic duality characterising that specific social interaction we define as an interview. Both (or more) partners have to be considered as necessary actors involved in giving shape to the “inter-view” as an ex-change of views.

Qualitative researchers call this ability “rapport” (Leech, 2002 :665), “contract” or “staging” (Legard et al., 2003 :139). In our specific understanding of the relational move through a “dialogical” Footnote 4 interviewing style, during the interview 1) the interviewer and the interviewee become the “listener” and the “narrator” (Chase, 2005 :660) and 2) a true dialogue between listener and narrator can only take place when they engage in an “I-thou” interaction (Buber 1923 /2008), as we will show below when we discuss selected examples from our own research.

As a communicative style, in a dialogical interview not only the researcher cannot disappear behind the veil of objectivity (Spencer et al. 2014 ), but the researcher is also aware of the relational duality–or “dialogueness”–inherent to the “inter-view”. Dialogical face-to-face interviewing can be compared to a choreography (Brinkman 2014 :283; Silverman 2017 :153) or a dance (La Mendola 2009 , ch. 4 and 5) where one of the partners (the researcher) is the porteur (“supporter”) of the interaction. As in a dancing couple, the listener supports, but does not lead, the narrator in the unfolding of her story. The dialogical approach to interviewing is hence non-directive, but supportive. A key characteristic of dialogical interviews is a particular way of “being in the interview” (see example 2 below) because it requires the researcher to consider the interviewee as a true narrator (a “thou”). Footnote 5

In a dialogical approach to interviews, questions can be thought of as frames through which the listener invites the narrator to tell a story in her own terms (Chase 2005 :662). The narrator becomes the “subject of study” who can be disobedient and capable to raise her own questions (Latour 2000 : 116; see also Lund 2014). This is also compatible with a critical realist ontology and epistemology, which holds that researchers inevitably draw artificial (but negotiable) boundaries around the object and subject of analysis (Gerrits and Verweij 2013). The case-based, or data-driven (ib.), character of QCA as a research approach hence takes a new meaning: in a dialogical interviewing style, although the interviewer/listener proposes a focus of analysis and a frame of meaning, the interviewee/narrator is given the freedom to re-negotiate that frame of meaning (La Mendola 2009 ; see examples 1 and 2 below).

We argue that this is an appropriate way to obtain case intimacy and in-depth knowledge for subsequent QCA, because it is the narrator who proposes meanings that will then be translated by the researcher, in the following moves, into set membership values.

Particularly key for a dialogical interviewing style is the question formulation, where interviewer privileges “how” questions (Becker 1998 ). In this way, “what” and “why” (evaluative) questions are avoided, where the interviewee is asked to rationally explain a process with hindsight and that supposedly developed in a linear way. Also typifying questions are avoided, where the interviewer gathers general information (e.g. Can you tell me about the process through which an urban project is typically built? Can you tell me about your typical day as an academic?). Footnote 6 “Dialogical” questions can start with: “I would like to propose you to tell me about…” and are akin to “grand tour questions” (Spradley 1979 ; Leech 2002 ) or questions posed “obliquely” (Roulston 2018 ) because they aim at collecting stories, episodes in a certain situation or context and allowing the interviewee to be relatively free to answer the questions.

An example taken from our own research on a QCA of large-scale urban transformations in Western Europe illustrates the distinct approach characterising dialogical interviewing. One of our aims was to reconstruct the decision-making process concerning why and how a certain urban transformation took place (Pagliarin et al. 2019 ). QCA has already been previously used to study urban development and spatial policies because it is sensitive to individual cases, while also accounting for cross-case patterns by means of causal complexity (configurations of conditions), equifinality and causal asymmetry (e.g. Byrne 2005 ; Verweij and Gerrits 2015 ; Gerrits and Verweij 2018 ). A conventional way to formulate this question would be: “In your opinion, why did this urban transformation occur at this specific time?” or “Which were the governance actors that decided its implementation?”. Instead, we formulated the question in a narrative and dialogical way:

Example 1 Listener [L]: Can you tell me how the site identification and materialization of Ørestad came about? Narrator [N]: Yes. I mean there’s always a long background for these projects. (…) it’s an urban area built on partly reclaimed land. It was, until the second world war, a seaport and then they reclaimed it during the second world war, a big area. (…) this is the island called Amager. In the western part here, you can see it differs completely from the rest and that’s because they placed a dam all around like this, so it’s below sea level. (…) [L]: When you say “they”, it’s…? [N]: The municipality of Copenhagen. Footnote 7 (…)

In this example, the posed question (“how… [it]… came about?”) is open and oriented toward collecting the specific story of the narrator about “how” the Ørestad project emerged (Becker 1998 ), starting at the specific time point and angle decided by the interviewee. In this example, the interviewee decided to start just after the Second World War (albeit the focus of the research was only from the 1990s) and described the area’s geographical characteristics as a background for the subsequent decision-making processes. It is then up to the researcher to support the narrator in funnelling in the topics and themes of interest for the research. In the above example, the listener asked: “When you say “they”, it’s…?” to signal to the narrator to be more specific about “they”, without however assuming to know the answer (“it’s…?”). In this way, the narrator is supported to expand on the role of Copenhagen municipality without directly asking for it (which is nevertheless always a possibility to be seized by the interviewer).

The specific “dialogical” way of the researcher of “being in the interview” is rooted in the epistemological awareness of the discrepancy between the narrator’s representation and the listener’s. During an interview, there are a number of “representation loops”. As discussed in the interpretative spiral (see Sect. 2 ), the analytical and membership moves are characterised by a number of research steps; similarly, in the relational move the researcher engages in representation loops or interpretative steps when interacting with the interviewee. The researcher holds ( a ) an analytical representation of her focus of analysis, ( b ) which will be re-interpreted by the interviewee (Geertz, 1973 ). In a dialogical style of interview, the researcher also embraces ( c ) her representation of the ( b ) interviewee's interpretation of ( a ) her theory-led representation of the focus of analysis. Taken together, ( a )-( b )-( c ) are the structuring steps of a dialogical interview, where the listener’s and narrator’s representations “dance” with one another. In the relational move, the interviewer is aware of the steps from one representation to another.

In the following Example 2 , the narrator re-elaborated (interpretative step b) the frame of meaning of the listener (interpretative step a) by emphasising to the listener two development stages of a certain project (an airport expansion in Barcelona, Spain), which the researcher did not previously think of (interpretative step c):

Example 2 [L]: Could you tell me about how the project identification and realisation of the Barcelona airport come about? [N]: Of the Barcelona airport? Well. The Barcelona airport is I think a good thermometer of something deeper, which has been the inclusion of Barcelona and of its economy in the global economy. So, in the last 30 years El Prat airport has lived through like two impulses of development, because it lived, let´s say, the necessary adaptation to a specific event, that is the Olympic games. There it lived its first expansion, to what we today call Terminal 2. So, at the end of the ´80 and early ´90, El Prat airport experienced its first big jump. (...) Later, in 2009 (...) we did a more important expansion, because we did not expand the original terminal, but we did a new, bigger one, (...) the one we now call Terminal 1. Footnote 8

If the interviewee is considered as a “thou”, and if the researcher is aware of the representation loops (see above), the collected information can also be helpful for constructing the study population in QCA. The population under analysis is oftentimes not given in advance but gradually defined through the process of casing (Ragin 2000 ). This allows the researcher to be open to construct the study population “with the help of others”, like “informants, people in the area, the interlocutors” (Lund 2014:227). For instance, in example 2 above, the selection of which urban transformations will form the dataset can depend on the importance given by the interviewees to the structuring impact of a certain urban transformation on the overall urban structure of an urban region.

In synthesis, the data collection process is a move on its own in the research process for performing QCA. Especially when the collected data are qualitative, the researcher engages in a relation with the interlocutor to gather information. A dialogical approach emphasises that the quality of the gathered data depends on the quality of the dialogue between narrator and listener (La Mendola 2009 ). When the listener is open to consider the interviewee as a “thou”, and when she is aware of the interpretative steps occurring in the interview, then meaningful case-based knowledge can be accessed.

Case intimacy is at best developed when the researcher is open to integrate her focus of analysis with fieldwork information and when s/he invites, like in a dance, the narrator to tell his story. However, a dialogical interviewing style is not theory-free, but it is “theory-independent”: the dialogical interviewer supports the narration of the interviewee and does not lead the narrator by imposing her own conceptualisations. We argue that such dialogical I-thou interaction during interviews fosters in-depth knowledge of cases, because the narrator is treated as a subject that can propose his interpretation of the focus of analysis before the researcher frames it within her analytical and membership moves.