1300 914 329

- ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ 5 star rating from 5000+ verified reviews

How to write a creative response

- by The Alchemy Team

So many exams are about learning facts and sticking to the same formula, so it should come as no surprise that students can find it difficult to break the mould when it comes to writing a creative response.

Fortunately, there are a number of techniques that can make it much easier to write a great creative response piece that’s reflective, insightful, and worthy of a great grade. Once you to know the format, you might even find that you enjoy this less restricted form of academic writing!

Why not get a HSC English tutor or a normal English tutor ?

What is a creative response?

Creative responses are English assignments that require students to tap into their creative side – picking up on the themes, commentaries, and ideas that are presented in a piece of literature that they’re studying.

The assessment is all about demonstrating your understanding of the literary techniques used in the text. Unlike other exams, though, you’re not being asked to critically analyse a text or demonstrate your understanding of the narrative.

Instead, the challenge here is to apply your knowledge and understanding of the text to create your own piece of writing that embodies the spirit and deploys the methods used in the literature you’ve been learning about.

How to format a creative response

Creative responses can take a couple of forms, so even though your writing will be relatively unrestricted, you still need to stay on topic and structure your writing in a relevant way.

Why not also read: How to Study for the HSC English Exam

It could be that you’re asked to write a brief narrative, a diary entry for an established character, or a short script. Either way, it’s likely to be a format that allows you to stretch your creative muscles and convey some of the ideas, feelings, and thoughts that the texts you’ve studied tap into.

Top tips for writing a creative response

Creative writing allows you to let loose with your own ideas, but that doesn’t mean your teachers and examiners aren’t looking for certain things. If you want to score the very best marks, consider the following whenever you’re writing a creative response:

Do express your views

Most people form views about the themes expressed in their English texts, but typical exam questions don’t really give you the space to explore those thoughts. Creative responses are your chance to think outside of the box and to make some arguments about the real world. Think about how the ideas and themes expressed in your text apply to the modern world, and use that to develop a narrative of your own.

Don’t focus too much on flowery language

The very best creative pieces use plenty of adjectives and descriptive phrases – but that shouldn’t be at the expense of a proper narrative. The point of these assessments is to convey your ideas, and getting too caught up on metaphors and expressive language could tip your writing over into the realm of poetry.

Do show, don’t tell

Even though you don’t need to go overboard with the flowery language, you still need to communicate your ideas in a way that showcases your understanding of the vocabulary, imagery and symbolism from the relevant text. Rather than saying that a character is “tired”, you should instead be saying that “their sunken eyes betrayed many late nights”. Unleash your inner author, and let those marks role in!

Achieve your full potential with VCE tutoring

Since 2005, Alchemy Tuition has worked with thousands of students to help them achieve the best possible results.

Why not also read: Top 5 Easiest VCE Subjects

All of our friendly and affordable tutors have been in the same shoes, studying hard and hoping to get a great grade. We know what the examiners are looking for, and we’ll help you (or your child) to excel with patience and a few study secrets!

To find out more, or to book an initial tutoring session, visit our site .

Search our archive:

Recent posts:

- How to motivate your teenager to study

- Technology use for primary school children

- The secret to studying smarter and not harder

- Why developing your child’s emotional intelligence is a must

- How to deal with a child who hates school

- Selective School

- Uncategorised

Get in touch

Let's create gold together.

Our office is closed from the 17th of December and will re-open on Wednesday the 4th of January 2023.

During this time you can still book a tutor here and we will get in touch to confirm when we re-open!

Office hours: Monday–Friday | 9AM–9PM AEST

We come to you

All suburbs of Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane or online everywhere.

AN ELITE EDUCATION AUSTRALIA PTY LTD COMPANY Level 36/1 Farrer Place, Sydney NSW 2000 ABN: 88606073367 | ACN: 606073367

- OC Test Preparation

- Selective School Test Preparation

- Maths Acceleration

- English Advanced

- Maths Standard

- Maths Advanced

- Maths Extension 1

- Maths Standard 2

- Maths Extension 2

- Primary Holiday Camps

- UCAT Preparation

- English Standard

- Business Studies

- Legal Studies

- UCAT Preparation Course Online

Select a year to see available courses

- Level 7 English

- Level 7 Maths

- Level 8 English

- Level 8 Maths

- Level 9 English

- Level 9 Maths

- Level 9 Science

- Level 10 English

- Level 10 Maths

- Level 10 Science

- VCE English Units 1/2

- VCE Biology Units 1/2

- VCE Chemistry Units 1/2

- VCE Physics Units 1/2

- VCE Maths Methods Units 1/2

- VCE English Units 3/4

- VCE Maths Methods Units 3/4

- VCE Biology Unit 3/4

- VCE Chemistry Unit 3/4

- VCE Physics Unit 3/4

- Castle Hill

- Strathfield

- Sydney City

- Inspirational Teachers

- Great Learning Environments

- Proven Results

- Jobs at Matrix

- Events and Seminars

- Book a Free Trial

Part 11: How to Write Creative Responses in Year 9 | The Basics of Narrative

Guide Chapters

- 1. How to make notes

- 2. Textual Analysis

- 3. How to analyse prose fiction

- 4. How to analyse poetry

- 5. How to analyse Shakespeare

- 6. How to analyse film

- 7. How to analyse images & visual texts

- 8. How to analyse prose non-fiction

- 9. Composing English responses in Year 9

- 10. How to write persuasive essays

- 11. How to write creative responses

- 12. How to write speeches & presentations

- 13. Year 9 Exam Skills

Unsure of how to write creative responses in Year 9? Don’t fear! We will go through different types of creative writing, things markers are looking for and a step-by-step process of how to write creative responses.

What is in this article?

Why must you write creative responses in year 9, types of imaginative writing tasks, what are markers looking for.

- How to write creative responses – Step-by-step

Creative writing in High School is about demonstrating your understanding of the techniques that you have studied.

In High School, most of your assessments require you to analyse texts, including novels and short stories.

This means that you should already have a good understanding of their structure, figurative language and how they convey meaning.

So, when you are asked to write a creative piece in Year 9, you are being assessed on your ability to put your knowledge into practice!

In Year 9, you can be asked to write 2 types of creative pieces: creative writing and creative re-imaginings.

Let’s see what they are.

Creative writing

Creative writing is a fictional piece of writing.

This is NESA ‘s definition of imaginative texts:

- Texts that represent ideas, feelings and mental images in words or visual images.

- Uses metaphor to translate ideas and feelings into a form that can be communicated effectively to an audience.

- Make new connections between established ideas or widely recognised experiences in order to create new ideas and images.

- Characterised by originality, freshness and insight.

Keep these dot points in mind when you write creative responses in Year 9. Focusing on these areas will help you build strong creatives.

Creative re-imaginings

According to NESA , creative re-imagining is a re-interpretation an existing piece of literature.

You may have come across some of these in your English classes or on the internet!

Here are some notable examples:

- Macbeth Retold (Macbeth)

- 12 Things I Hate About You (Taming of the Shrew)

- A Cinderella Story (Cinderella)

- Gnomeo and Juliet (Romeo and Juliet)

So, why do people re-imagine existing literature?

While some values and circumstances can change with the times, other qualities of being human remain the same.

Literature always reflects the context that it is composed in.

This includes the composer’s personal, social, historical, economical and political contexts.

However, times are always changing. This means that hot topic issues and widely accepted perspectives are also changing.

For example, climate change is a relatively recent phenomenon. You wouldn’t find Shakespeare commenting on this issue.

But remember, many things in our society stay constant. These are usually elements of the human experience or deeply ingrained social issues.

For example, human’s thirst for power or the expectations of men and women during different places and times (eg. patriarchal values).

So, when composer’s re-imagine texts, they force audiences to compare the two contexts.

We notice similarities and differences by identifying what the composer kept and changed.

When you write creative re-imaginings, keep this point in mind!

When you write creative responses in Year 9, there are some things that you need to keep in mind.

Let’s see what they are:

Characterisation

No one wants to read about a basic, cliche, stock-character.

So, when you write creative responses in Year 9, you need to make them complex .

They have flaws, motivations, and even mixed intentions. Basically, they are realistic.

So, how do we create complex characters when we write creative responses in Year 9?

You need to build a strong understanding of your character.

Some basic points that you MUST know are:

- Personality

- Where they live

- What time period are they living in?

- What is their relationship with or to the other characters?

These are some points that you SHOULD know to make your characters more complex:

- Likes and dislikes

However, even though you know your character well, you don’t need to share everything with the reader.

Don’t mention all of this information when you write creative responses in Year 9.

Only bring them up what is necessary to your plot.

When you create complex characters, you give them space to grow and change. They can ‘fix their flaws’ as the story continues.

This is your character arc !

It is important that your characters are always changing and growing. No one wants to read about a character who stays the same for the whole story.

When you write creative responses in Year 9, you need to have an interesting and original plot to get good marks.

Here are some tips:

- Have a complication

When there is a complication, there is a goal… whether it is defeating the dark lord, or dating the new boy or girl.

Having a complication will make your plot more entertaining and meaningful.

- Avoid cliches

Cliches are unoriginal, over-used, and predictable ideas and phrases.

Using cliches when you write creative responses in Year 9, will make your stories seem lazy and lack creativity.

Setting provides the backdrop to your creative responses. This is where all the events occur and what shapes your characters. Settings are more important than you think!

So, it is important that you pick the right setting when you write creative responses in Year 9.

Here are are some tips:

- Think about the mood/atmosphere you want for your stories

Different moods and atmospheres will shape the reader’s expectations about your stories. These can be created through your setting.

For example, an empty forest at night will have a spooky atmosphere. Readers assume that something bad is going to happen and feel the tension.

On the other hand, a bright, sunny beach gives off a happy and exciting vibe. Readers will feel cheered by this.

Select your settings carefully because they will help you create meaning.

- Stick to facts

You need to make sure that your facts are accurate when you choose to use a real-life setting or historic period.

Your characters can’t use phones in Ancient Egypt, because phones didn’t exist at that time! Unless your story is about time travel…

People don’t want to read a story that has their facts mixed up (things out of time are called “anachronisms”). It will draw their attention away from the plot, and focus on the inaccurate facts.

Incongruities and plot holes draw people out of the story.

So, make sure that you research enough about the context you want to use. Even if it is set today .

Dialogue is the element that students struggle with most.

Some student misuse dialogue. Other’s punctuate them incorrectly. And some don’t use them at all because they’re too scared.

But using dialogue when you write creative responses in Year 9 shouldn’t be hard!

Let’s see how we can change that:

- Only write meaningful dialogue

Too often, students write dialogue that don’t serve any purpose. Like, “Hi! How are you doing” or “I’m good thanks!”.

However, you need to remember that stories are not a minute-to-minute recount of someone’s day. Instead, stories are meant to be concise and effective.

Everything has to serve a purpose. It either advances the plot or develops characterisation.

Dialogue works in the same way. Don’t include filler sentences. They take up word space, and they don’t serve a purpose.

Only write what is necessary.

- Use correct punctuation!

In Year 9, many students still misuse punctuation when they write dialogue.

One important rule to remember is the hamburger rule .

Basically, this is a good way to remember that all punctuation goes INSIDE the speech marks.

Here are some CORRECT examples:

“I want to eat a hamburger,” John said.

“Do you want to eat something? I’m feeling like a hamburger.”

“I’m hungry,” John said as he stood up, “Let’s eat hamburgers!”

Here are some INCORRECT examples:

“I want to eat a hamburger”, John said.

“Do you want to eat something?” “I’m feeling like a hamburger”

“I’m hungry”, John said as he stood up. “Let’s eat hamburgers!”

Do you notice the differences?

If you want to learn more about grammar rules, read our essential guide to English grammar .

Employing figurative devices

It is important that you are consistently improving your writing as you progress through High School.

One way to do this is by using figurative devices when you write creative responses in Year 9.

Why do we need to use figurative language?

Well, you would have heard about “ show, don’t tell “, before. Figurative language helps you achieve this.

Essentially, when you are telling , you are simply stating what happened.

Eg. Sally was embarassed.

However, when you show what happened, you are painting a picture for your readers. They need to take in the information and deduce what is happening.

Eg. Sally’s face turned as red as a tomato.

Notice the difference?

Basically, figurative language is an advanced way of showing what is happening.

Think, metaphors , symbolism , personification etc.

They all convey meaning in a much more memorable and effective way than telling. This is because readers take more meaning away when they have to do the work themselves and infer things.

Click HERE to see a list of literary techniques that you can use when you write creative responses in Year 9.

How to write creative responses in Year 9 – Step-by-step

So, now that you know what the markers are expecting, let’s see how we can put all of it together.

We will go through a step-by-step process to write creative responses in Year 9.

It is crucial that you plan because it actually saves you time when you write!

You don’t need to stop and think about what’s happening next in your story. You just write!

To plan, you need to:

1. Brainstorm

You need to carefully read the question, stimulus and/or prompt.

Identify any keywords and important ideas that you need to address.

Now, write down everything you can think of about these ideas; plots, characters, settings, messages and so much more!

Even if you think the idea is bad, jot it down anyway.

The point of brainstorming is just to get the ball rolling in your mind.

However, remember to set yourself a time limit!

Give yourself a few minutes to brainstorm. You don’t want to get too caught up in this step. There’s still a lot to do.

Now you need to decide which ideas you want to write about.

To do this, ask yourself to questions:

- Is this something that I am interested in?

- Does it relate to the question/stimulus/prompt?

If you answer yes to both, then it is a possible story idea!

3. Scaffold

Now that know what you want to write, you need to figure out the fine details.

- Perspective : Whose perspective will the story be told?

- Who : Who is the protagonist?

- What : What is the problem?

- When : When do things take place?

- Where : Where is it happening?

You need to scaffold a rough outline of your plot too! Read the next section to see how.

Also, you can read this article to learn HOW TO WRITE NOTES .

Structure: Three act structure

When you write creative responses in Year 9, you need to make sure that it follows the three-act structure.

This ensures that your story progresses and is interesting to read.

So, what is the three-act structure?

- Orientation : Establishes the story world, characters and introduces the conflict.

- Complication : Protagonist attempts to solve the problem… but things seem to get worst.

- Resolution : The problem is ‘resolved’. Events settle down and the story wraps up.

When you write your story plan, make sure you know the rough events for each section. This will ensure that you have a progressive creative response.

It is important that you think about characterisation in your planning stage.

We already went through what characterisation is and how to do it. But, here’s a quick reminder:

Characterisation is the creation of a 3-dimensional, complex character and their growth throughout the story.

You can refresh your knowledge about characterisation in detail above .

Openings-hooks

How your story begins is very important. Opening-hooks are basically the first thing your reader reads.

Usually, it is the deciding factor between someone keeping the book opened and closing it.

“One sunny day, Jamie woke up and got out of bed. He quickly brushed his teeth, changed into his suit, and ran downstairs.”

Now read this:

“Hurry up!”

Jamie’s eyes shot open. There was no need to look at the clock. Jamie knew he was late for his interview.

Which one is more interesting to read?

You see, your opening-hook is very important. It has to ‘hook’ the reader’s attention and ‘reel’ them in.

So, how do you write great opening hooks?

Start with:

- Dramatic action or speech

- Hint about the complication

- Something unexpected

- An indication of change.

These opening will create suspense and spark curiosity to keep your reader wanting to know more.

Drafting and editing

When you write creative responses in Year 9, expect to have numerous drafts.

You should be constantly drafting, redrafting and editing your work to produce the best possible creative.

Drafting is putting your ideas into words and simply writing!

Drafts are meant to be imperfect.

Your aim is to get your ideas on paper, not write perfect sentences.

To draft, you need to:

- Revise your plan : Know what you are going to write. This includes your characters, plots, themes etc.

- Start writing! Don’t be afraid to start. Remember, drafts are meant to be imperfect .

- Don’t stop writing. it might be tempting to go back and edit as you draft your creative responses. But don’t do this! Stop worrying about how your sentences sound… just get your ideas out!

- If you get stuck, write another part : You don’t want to stop your writing flow! So, instead of wasting 30 minutes trying to formulate the sentence, just write another paragraph! You can always go back and finish it up later

Editing is basically reading over your creative responses and fixing it to make it better.

To edit, you need to:

- Fix grammatical, punctuation and spelling errors .

- Reword and rewrite sentences and paragraphs : If you don’t like the way a sentence or paragraph sounds, then this is your chance to change it. Sometimes, you might have to rewrite whole paragraphs.

- Make sure everything makes sense : If something is confusing, remove or change it! Sometimes, you need to restructure your whole creative response to do this.

- Add more figurative language : Take this chance to add some techniques in your story to make it stronger.

Yes, drafting and editing is a lengthy process… Sometimes, you might even end up with 5 different drafts.

But is worth the time and effort.

Many students don’t ask for feedback because they don’t see the importance of feedback, or they don’t know who to ask.

Feedback is very important because it will help you:

- Identify your common mistakes and fix them :

Most people have some bad writing habits that they never notice. Feedback will help you identify these, so you can fix them.

- Improve your general writing skills :

When you get feedback, you build good writing habits. You begin to identify your mistakes and continually edit your work.

- View your writing from a new perspective :

When you put so much effort and time in your writing, you will struggle to critique it. So, getting feedback will show you a different perspective of your writing. Then, you can go back and edit or keep things.

- Produce a strong creative :

After numerous feedback and editing sessions, your final creative will be very strong.

So, to get feedback, you should:

- Ask people who can give you constructive feedback :

This can be your school or Matrix teachers, classmates, or even your parents. Remember, there is no point asking someone who can’t give you constructive feedback because it will just confuse you more. So, be selective in who you choose.

- Ask MANY people :

It’s always a good idea to get a second, third, and even fourth opinion. Different people will have different critiques.

- Prepare a set of questions you want them to focus on :

Don’t just hand your essay and ask for feedback. Tell your readers what you expect from them. Does the story makes sense? Are there any grammatical errors? Be specific.

- Always edit your work after :

There is no point in getting feedback if you are not incorporating it in your writing. However, also be selective about what you want to fix. Not all feedback are good.

Final piece

After a long process of planning, researching, drafting, editing, and more editing, you will have your final creative writing piece.

Remember, you can’t keep editing forever and ever.

You need to know when to sit down and be satisfied with your writing.

Be proud of what you produced.

Part 12: How to Write Speeches and Presentations in Year 9 English

© Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au, 2023. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Matrix Education and www.matrix.edu.au with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Related courses

Year 9 english.

Year 9 English tutoring at Matrix is known for helping students build strong reading and writing skills.

Learning methods available

Level 9 English course that covers every aspect of the new Victorian English Curriculum.

More essential guides

The Beginner's Guide to Year 9 Maths

Part 1: How to Write English Notes for Year 9

The Essential Guide To English Techniques

How to write a text response

WHAT IS A TEXT RESPONSE?

In this guide, we will cover everything you need to know about writing a text response. Let’s start at the beginning.

A text response is a style of writing in which you are sharing your reaction to something. It is an opportunity to let the world know how you feel about something.

A text response can also be referred to as a reader response which is accurate, but you may also confuse them with a literacy narrative. This is not an accurate comparison, as a literacy narrative is more an assessment of how you became literate. In contrast, a text response is a specific response to a specific text.

A text response is specifically a response to a book you have read. Still, it can also be a response to a film you have just seen, a game you have been playing, or for more mature students; it could be a response to a decision the government is making that affects you or your community that you have read from a newspaper or website.

When writing a response, it is vital that you get the following points across to your audience.

- How do you feel about what you are reading / saw / heard?

- What do you agree or disagree with?

- Can you identify with the situation?

- What would be the best way to evaluate the story?

Some teachers get confused between a book review and a text response. Whilst they do share common elements, they are unique genres. Be sure to read o ur complete guide to writing a book review for further clarification.

WHAT IS THE PURPOSE OF A TEXT RESPONSE?

Often when we talk about the development of language skills, it is useful to discuss things in terms of four distinct areas. These are commonly grouped into the two active areas of speaking and writing and the two so-called passive areas of listening and reading. Learning to write a text response bridges this gap as it requires our students to not only develop high-level writing skills but also to consider reading as much more than a mere passive activity.

Writing a text response hones the student’s critical thinking skills and ability to express their thoughts in writing. It gives students an opportunity to engage in reading as an active exercise, rather than something that is analogous to watching TV!

A COMPLETE TEXT RESPONSE BUNDLE FOR STUDENTS

2 in-depth units for students and teachers to work on as a class or independently. Packed with teaching resources and lesson ideas.

160 PAGES of high-quality teaching units for all ages and abilities. NO PREPARATION IS REQUIRED. DIGITAL and PRINT to DOWNLOAD NOW.

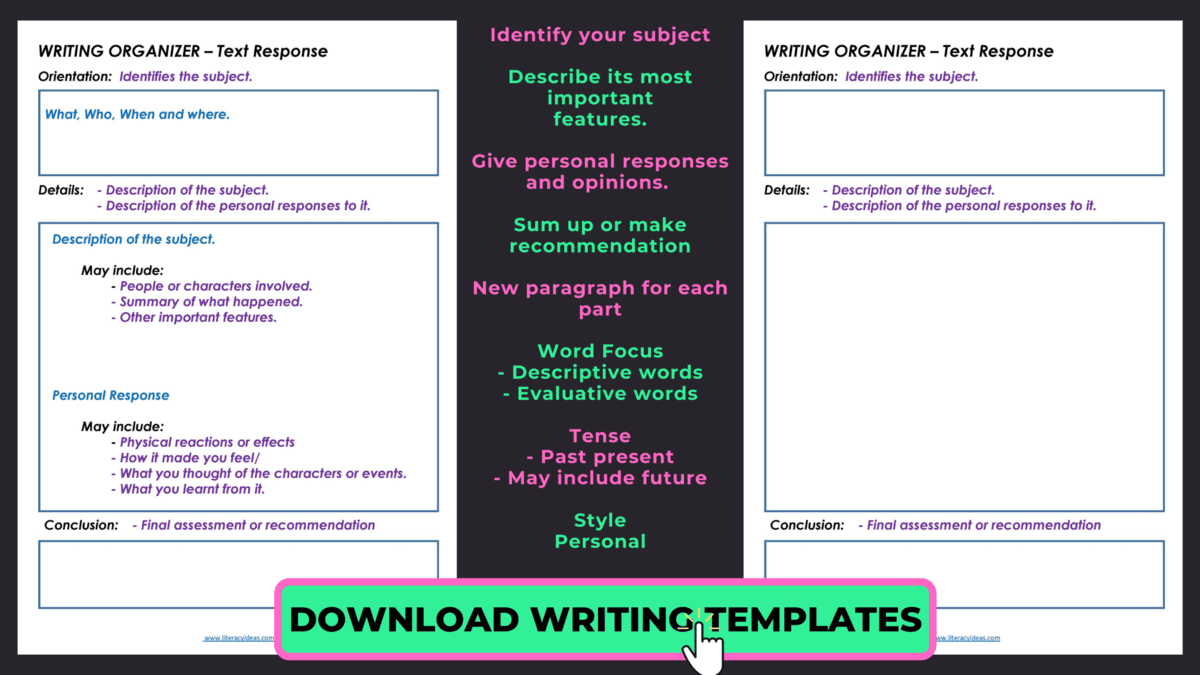

TEXT RESPONSE STRUCTURE

KEEP IT FORMAL This is a calculated and considered response to what you have read or observed.

USE EVIDENCE Frequently refer to the text as evidence when having an opinion. It becomes the reference point for all your insights within your text response.

HAVE AN OPINION This is not a recount. This is your OPINION on what the author or film producer has created. Don’t shy away from that.

TENSE & STYLE Can be written in either past or present tense. Feel free to use your own style and language but remember to keep it formal.

TEXT RESPONSE FEATURES

YES or NO? Essentially you are making a recommendation. Ensure your audience know where you sit.

LET US INSIDE YOUR MIND How did it make you feel? What did you learn from it? Did you engage with the characters?

SHOW SOME BALANCE Even if you passionately loved or hated the text your audience will view you as biased if you solely focus on one angle. A little balance will give you credibility.

GETTING STARTED: THE PREWRITING STAGE OF A TEXT RESPONSE

As with much of the formal school experience, students can greatly benefit from undertaking a methodical approach in their work. The following process outlines step-by-step how students can best approach writing their text responses in the beginning.

The keyword in the phrase writing a text response is not writing but response . The whole thing starts with the reading and how the student considers the text they are engaging with. Whether the text they are being asked to respond to is an unseen piece in an exam situation or a piece of coursework based on something studied over a semester, the structure remains the same. This is true, too, regardless of age and ability level. Younger students should be taught to approach writing a text response using the same concepts but in a simplified and more scaffolded manner.

Read for Understanding:

Students should read the text they are responding to initially for a basic comprehension of what the text is about. They should read to identify common themes and narrative devices that will serve to answer the question. Often, the question will demand that the student consider and explain the author’s use of a specific literary device or how that literary device develops a central idea and the author’s purpose. In preparing our students to write competent text responses they must first be familiar with the literary devices and conventions that they will be asked to discuss.

Students may instinctively know what they like to read, but what is often not instinctive is the expressing of why they like to read it. They may acknowledge that the writing they are reading is of a high quality, or not as the case may be, but they may lack the vocabulary to express why the writing is successful or unsuccessful. Take the opportunity in class when reading, regardless of the genre, to point out literary devices , techniques, and stylistic considerations that will help your students when it comes to writing a text response.

As humans, we are hardwired to understand the world around us in terms of the stories we tell ourselves and others. We do this by employing comparisons and drawing parallels, we play with words in our everyday use of idiom and metaphor, alliteration and rhyme. Encourage students to keep an ear out for these techniques in the music they listen to, the comics they read, and the TV they watch. Even in the advertising they are exposed to.

Be sure too to offer your students opportunities to practice writing their own metaphors, similes, alliterative sentences etc. There is no better way to internalize an understanding of these literary techniques than by having a go at writing them yourself. And, it doesn’t have to be a dry academic exercise, it can be a lot of fun too.

Teaching alliteration? Have the students come up with their own tongue twisters. Want them to grasp simile? Have them produce Not! similes, for example, give them an adjective such as ‘cuddly’. Tell them you want them to write a simile using the simile structure employing ‘as’. Tell them too they must use the word ‘cuddly’ about someone who is not cuddly at all. Offer them the example He is as cuddly as a cactus to get the ball rolling. They can do this for any adjective and they will often achieve hilarious results!

Read Directions Carefully:

It should go without saying to read the directions carefully, but experience teaches us otherwise! Often it is not the best writers among our students who receive the best grades, but those who diligently respond to the directions of the task that has been set. Students should be sure to check that they have read the directions for their text response question closely. Encourage them to underline the keywords and phrases. This will help them structure their responses and can also serve as a checklist for them to refer to when they have completed writing their text responses.

Have students pinpoint exactly what the question is asking them. For older or stronger students, these questions will likely comprise several parts. Have the student separate the question into these component parts and pinpoint exactly what each part is asking them for.

A good practice to ensure a student has adequately understood what a question is looking for is to ask the student to paraphrase that question in their own words. This can be done either orally or as a written exercise. This helpful activity will inform the student’s planning at the prewriting stage and, as mentioned, can provide a checklist when reviewing the answer at the end.

The Process:

- To ensure students fully understand the question, have them underline or highlight keywords in the sentence or question. Distribute thesauruses and have students find synonyms for the keywords that they have highlighted.

- Have them rewrite the question as a series of questions in their own words. This will allow the teacher to assess their understanding of what they are being asked to do. It can also serve as a structured plan for writing their response.

- Allow some time for students to discuss the question together, either in small groups or with talking partners. After the allotted time, students must decide on a yes , no , or maybe response to the central question.

- Their response to Step 3 above will formulate their contention, which will serve as the driving force behind their text response as a whole.

- On their own, students brainstorm at least three arguments or reasons to support their contention.

- For each of the reasons, students should refer to the text and choose the best evidence available in support of their contention.

- Students should not be overly concerned with forming a logical order for their notes gathered so far. This activity aims to let ideas flow freely and capture them on paper.

When completed, it is at this point that they are ready to begin the writing process in earnest.

HOW TO WRITE A TEXT RESPONSE

As with writing in many other genres, it is helpful to think of the text response in terms of a three-part text response essay structure. It is a simple process of learning how to write a response paragraph and then organizing them into the ubiquitous beginning, middle, and end (or intro, body, and conclusion) that we drill into our students will serve us well again. Let’s take a look:

The Introduction:

The first paragraph in our students’ text responses should contain the essential information about the text that will orientate the reader to what is being discussed. Information such as the author, the book’s title or extract, and a general statement or two about the content will provide the reader with some context for the discussion.

The SOAPSTONE acronym is useful when considering which information is essential to include in the intro: Speaker, Occasion, Audience, Purpose, Subject, and TONE. Students should reflect on which aspects should be addressed in the introductory paragraph. The genre of the text will largely determine which of these should be included and which are left out. However, it is important the student does not get too bogged down at this stage; these orientation sentences usually require only three or four sentences in total.

Be sure to check out our own complete guide to writing perfect paragraphs here .

The tone of a text response should be such that it assumes the reader does not understand the text that the writer does. It is useful to tell them here to picture one person in their life they are writing to. Someone that would not be familiar with the text, perhaps a family member that they are explaining what they read. Remind them, though, the language should be formal too.

Once the student has established some context in the reader’s mind, they will need to address the central idea forming the ‘eye of the storm’ of their argument.

When learning how to write a text response body paragraph, one of the most common pitfalls students fall into is engaging in a straightforward retelling of the text. Discussion of the text is the name of the game here. Students must get into the text and express their opinions on what they find there. It is quickly apparent when reading a student’s response when they are merely engaging in a retelling and delivering a thoughtful response. Be sure students are aware of the fact that this fools nobody!

The notes students have made in the prewriting stages will be extremely useful here. Each of the arguments or reasons they have produced to support their contention will form the basis for a body paragraph. The TEEL acronym is useful here:

Topic Sentence : Students should begin each paragraph with a topic sentence. This sentence introduces the point that will serve as the main idea of the paragraph – the central riff, if you like. It will engage directly with an aspect of the question or writing prompt .

Expand / Explain: The purpose of the next few sentences will be to narrow the focus of the topic sentence, often by referring to a specific character or event in the text and offering a further explanation of the central point being developed in the paragraph.

Evidence / Example: At this point in the paragraph, it is essential that the student makes close reference to the text to support the point they have been making. Having an opinion is great, but it must be based, and be shown to be based, on the actual text itself. Evidence will most often take the form of a quotation from the text – so make sure your students are comfortable with the mechanics of weaving quotations into their writing!

Link: The end of each body paragraph should link back to the student’s central contention. It restates the argument or reason outlined in the topic sentence but in the broader context of the central contention which usually is the yes , no , or maybe uncovered at the prewriting stage.

As the student moves through their essay, it is important that they reference the main theme of the text in each and every paragraph. The structure of the essay should illustrate an evolution of the student’s understanding of that theme.

References should be made to how the writer employs various literary techniques to construct meaning in his or her text. However, reference to literary techniques should not be made merely in passing but should be integrated into a discussion of the themes explored in the essay.

Writing a text response conclusion:

Writing the conclusion involves essentially restating the contentions made already, as well as summarizing the main points that were discussed. Though the conclusion will inevitably have much in common with the introduction, and some repetition is unavoidable, make sure students use different wording in their conclusion. The paraphrasing exercise in the prewriting stages may be helpful here.

Encourage students too to link back to their reasons and arguments developed to support their contention in the body paragraphs. The conclusion is no place to introduce new ideas or to ask rhetorical questions. It is the place for gathering up the strands of argument and making a statement about the relevance of the text in relation to the wider world.

TIPS FOR WRITING A GREAT TEXT RESPONSE

● In essays of this type, students should mostly write in the present tense.

● Encourage students to vary the length of their sentences to maintain the reader’s interest. But be careful too, students should avoid using overly long sentences as longer sentences can be more difficult to control. A good rule of thumb is that when expressing complex thoughts use several short sentences. Simpler thoughts can be expressed through longer, more complex sentences.

● Tie everything back to the question. The dissection of the question during the prewriting stage of the text response should remain at the forefront of the student’s mind at all times. If what the student writes doesn’t link back to the original question then it is deadwood and should be discarded.

● Writing a text response requires the student to analyze the text and responds personally with their own thoughts and opinions. They should not be afraid to make bold statements as long as they can make references to the text to support those statements.

● The prewriting stage is essential and should not be skipped. But, even with a well thought out prewriting session, where time allows, opportunities should be given for students to draft, redraft, and edit their writing.

We often teach our students that writing is about expressing our thoughts and ideas, but it is also about discovering what we think too.

TEXT RESPONSE TASK FOR STUDENTS

In a response paper, you are writing a formal assessment of what you have read or observed (this could be a film, a work of art, or a book), but you add your own personal reaction and impressions to the report.

The steps for completing a reaction or response paper are:

- Observe or read the piece for an initial understanding

- Record your thoughts and impressions in notes

- Develop a collection of thoughts and insights from

- Write an outline

- Construct your essay

Once you have established an outline for your paper, you’ll need to respond using the basic elements of every strong essay, a strong introductory statement.

In the case of a reaction paper, the first sentence should contain the title of the object to which you are responding and the name of the author/creator/publisher

The last sentence of your introductory paragraph should contain your stance or position on the subject you are writing about.

There’s no need to feel shy about expressing your own opinion in a response, even though it may seem strange to write “I feel” or “I believe” in an essay.

USEFUL STATEMENTS TO INCLUDE IN A TEXT RESPONSE

- I felt that

- In my opinion

- The reader can conclude that

- The author seems to

- I did not like

- The images seemed to

- The author was [was not] successful in making me feel

- I was especially moved by

- I didn’t get the connection between

- It was clear that the artist was trying to

- The sound track seemed too

- My favorite part was…because

Teaching Resources

Use our resources and tools to improve your student’s writing skills through proven teaching strategies.

TEXT RESPONSE GRAPHIC ORGANIZER

TEXT RESPONSE WRITING CHECKLIST & RUBRIC BUNDLE

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ (92 Reviews)

VIDEO TUTORIALS FOR TEXT RESPONSE WRITING

OTHER GREAT ARTICLES RELATED TO TEXT RESPONSE WRITING

How to Write a Book Review: The Ultimate Guide

Transactional Writing

How to write an Argumentative Essay

How to Write an Advertisement: A Complete Guide for Students and Teachers

How to write a perfect 5 Paragraph Essay

Unit 3: Summarizing and Responding to Writing

17 Response Techniques

The goal of a response essay is to communicate to the reader your personal viewpoint, experience, or reaction to a text. A response has two parts: First, tell the reader what important idea from a text you want to respond to. Next, convey your reflections on the idea through one of the techniques below.

Characteristics of a response

- A response begins with an idea that is interesting to you or you feel is important.

- A response is subjective, expressing your opinion or perspective.

- Personal experience – Write about something you experienced (or someone you know) that relates to an idea in the article.

- Agree or disagree – Identify a point you agree or disagree with and explain why.

- Application – Identify an idea or information in the article and apply it to something you have seen or heard before. You might compare something in the article to something you previously learned or analyze an idea in the article based on information you already know.

Three techniques for writing a response

When writing response, read the article and imagine you are talking to the writer. What questions might you ask? What comments might you make? How might you relate to the ideas in the article? Take notes in the margins as you read. You can use these notes later as you write your response.

The following examples respond to ideas from Megan Gambino’s (2011) article “How Technology Makes Us Better Social Beings.”

Example 1: Personal experience response

One issue from the article that I’d like to discuss is the positive effect of using social websites. ** Keith Hampton, a sociologist of the University of Pennsylvania says, “People who use sites like Facebook actually have more close relationships and are more likely to be involved in civic and political activities” (as cited in Gambino, 2011, p. 40). The author’s point is that after using social networking, people care more about the political events and the relationship between each other is also better.

In fact, the Internet and SNS have made us, as active citizens and “social beings” as Gambino says, more connected and united than ever before. I agree with his sentiment and can illustrate it with a personal example. When I first left my country to come to the United States to pursue my university degree, it was the first time ever in my life to be so far away from home to study without knowing anyone in a place. Fortunately, I got an invitation from Malaysian Undergraduate Student Organization of Madison to join their group on Facebook before I left my country. As a result, meeting other Malaysian students in Madison before I arrived, I felt much better prepared and more confident in my journey to next the part of my life. Even now, I use SNS to make new friends and stay in contact with my high school best buddies every day. Although I do not go out to bars or parties to meet new friends and I am miles apart from my high school besties, I am still able to interact and socialize with them as a result of technology and SNS.

EXERCISE #1 :

- Identify the issue/idea this response will focus on.

- Identify the quotation.

- Identify the paraphrase and the words that introduce the paraphrase.

- How does the writer share their personal experience and relate it to the article? Identify an interesting detail the writer uses in the response.

Example 2: Agree/disagree response

Another idea I’d like to respond to focuses on how people rely on the Internet. Gambino (2011) states, “About 25% of those observed using the Internet in public spaces said that they had not visited the space before they could access the Internet there” (p. 41). In other words, people already take Internet as an important part in their life and expect to access it wherever they go.

I strongly agree with this argument. For example, I am taking six courses this semester, and three-quarters of my homework and readings are posted online. If the Internet is inaccessible in my resident hall, I will definitely consider moving out. Moreover, I only visit buildings on campus where the wifi signal is strong. Most of the libraries are good for this, but I found the connectivity in Van Vlek Math Building is not so good, so I don’t go there anymore. I am not a geology major, but my friend told me the wifi in the geology library is really fast, so now I study there in the afternoons. In short, I definitely feel that accessibility to the Internet heavily influences whether or not people will use a public space.

EXERCISE #2

- How does the writer share their personal opinion and relate it to the article? Identify an interesting detail the writer uses in the response.

Example 3: Application response

One important topic that I’d like to address is how people use technology in public areas. Keith Hampton, a sociologist of the University of Pennsylvania said, “Laptop users are not alone in the true sense because they are interacting with very diverse people through social networking websites, e-mail, video conferencing, Skype, instant message and a multitude of other ways” (as cited in Gambino, 2011, p. 40). This means that people who use mobile technology in public areas in fact communicate and share information with people through social networking sites, video, e-mail and many other media, and hence they are not isolated.

This reminds me of why Mark Zuckerberg wanted to create Facebook. He originally created it to build connections among students at Harvard University, but it has grown to become a way to bring people together from anywhere in the world. By 2006, it became accessible beyond universities to anyone with an email address (Phillips, 2007, p. 1). What he initially thought would be just limited to one school has become a way for people around the world to connect with each other, and now most people seem to use it on their mobile devices at any time or in any place. Through Facebook, and other social networking sites, people do not have to feel alone any more, even if they are sitting alone in a Starbucks drinking a coffee.

EXERCISE #3:

- How is the application example different from the previous examples? Identify an interesting detail the writer uses in the response.

Academic Writing I Copyright © by UW-Madison ESL Program is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Support Sites

English A: Language and Literature Support Site

Creative response, instructions.

A creative response is a text that you create in response to another text or set of texts, in order to show your understanding of that text and a text type. Imagine writing several diary entries from the perspective of a character from a novel or play. Imagine writing a letter of complaint in response to an offensive advertising campaign. Imagine writing a news article on events that unfold in a novel. Imagine writing an opinion column in the style of an actual columnist. Good creative responses show an understanding of both the stimulus text(s) and the text type that you are trying to emulate. The type of text that you choose to write should be appropriate for showing your understanding of the stimulus text the intentions of the (imaginary) author. Your teacher may let you chose from a list of text types. Your creative response should be between 800 and 1,000 words, of which at least 200 words are used on used to describe the WHY, HOW and SO WHAT in your portfolio. Use the assessment rubric below to evaluate your work.

Model portfolio entry

WHAT: here is the news article that I created in response to The Great Gatsby .

Mystery shrouds death of Jay Gatsby 26 October, 1922 Peter Parker for the New York Post

Businessman and socialite gunned down in his own swimming pool.

NEW YORK - Police have confirmed the identity of the body found earlier today in the swimming pool of the Gatsby estate in West Egg to be that of entrepreneur and socialite Jay Gatsby. Authorities are operating on the theory that he was murdered by auto-mechanic George Wilson, whose body was found in the woods near the estate. Wilson is thought to have murdered Gatsby out of revenge before turning the same revolver on himself.

The murder-suicide comes after Myrtle Wilson, George Wilson’s wife, was killed in a hit-and-run incident on the previous evening outside her husband’s gas station near Flushing in the ‘Valley of Ashes’. Witnesses claim that the perpetrator drove a yellow Rolls Royce.

During the investigation of the Gatsby murder, police discovered a yellow Rolls Royce with bloodstains and a broken headlight on the premises of the Gatsby estate. It is unclear, however, if Mr. Gatsby was personally involved in the hit-and-run incident, as witnesses claim to have seen a woman driving the automobile. The identity of the woman remains unknown, and the investigation is ongoing.

Jay Gatsby was last seen leaving the Plaza Hotel in Manhattan on 25 October around 7 p.m. He had rented a suite there for the afternoon. From his suite, a heated argument was heard by guests. Receptionists confirm that he left the suite with a woman in a fit of rage.

Persons with information on the murder of Mr. Gatsby and Mrs. Wilson are asked to come forward and provide local authorities with this information to assist investigations further.

Little is known about Jay Gatsby, despite the lavish parties that were hosted at his West Egg mansion. It is believed that his extravagant lifestyle was financed by a flourishing business in the illegal distribution of alcohol. One acquaintance of Gatsby’s, who wishes to remain anonymous, claims to have seen Gatsby with New York crime kingpin Meyer Wolfsheim, though this cannot be confirmed.

To some, Jay Gatsby was known as an ‘Oxford Man’, though there is no record of him attending any college in Oxford, England. Sources within the US Army, however, confirm that he received a scholarship to attend schooling in Oxford after his valiant efforts in the Great War. Drafted into the Army, Gatsby quickly rose to the rank of Major. Rumors that Gatsby was a German spy appear to be ill-founded.

Gatsby’s neighbor, Nick Carraway, had this to say about him: “Gatsby was misunderstood by many, but he was a good man with a clear focus.” When asked what captured the focus of this aloof, though well-known man, Carraway, answered vaguely. “His focus was on the past, and regaining what he had lost years ago. But it was in vain. He was like a boat rowing against the tide. And the world of Old Money will never give an inch to people like Jay Gatsby, people with New Money. They have to row their own boat. And for Gatsby, he simply wasn’t strong enough.”

It is thought that Jay Gatsby is survived by none. Any family members or relatives are asked to make themselves known to the County of Great Neck.

An estate-sale will be organized by Nick Carraway and friend Jordan Baker on the 1 st of November. Proceeds from this sale will benefit the Golf for Youth Foundation, of which Ms. Baker is the founder.

An open funeral will be held at Great Neck Memorial on October 31 st at 3 p.m.

WHY: In class we read The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald, which I really liked. The movie, starring Leonardo Di Caprio, also inspired me to write a creative response about it. I think I am going to write my Paper 2 essay about The Great Gatsby and so this creative response has been done as a kind of preparation for my exams. We also studied news articles in class and the language of reporting, so I wanted to show my understanding of text type.

HOW: I talked to my teacher in preparation for this activity. When I said that I wanted to do my creative response on Gatsby, he said that the news article might be a good text type for it, because there were so many dramatic events, like the murder of Gatsby and Myrtle. I re-read the last chapters with this idea of writing a news article in mind. I also studied the language of news articles and found that they used the present perfect a lot and the passive voice. I wanted to imitate this style in my piece by writing from the perspective of a journalist, who did not know who killed Myrtle or Gatsby. I also wanted to squeeze Nick Carraway into the piece too, so I pretended that the police interviewed him after the murders.

SO WHAT: I really enjoyed this assignment. In fact, my sister, who works on the school newspaper, read it and she suggested that I write for the school newspaper too. I don't know about that, but I'm happy I did it. I also feel like I have a better understanding of the novel now, in preparation for my Paper 2 exam next May. I also feel I did well on the assessment rubric, giving myself a 3 on criteria A, a 6 on B and a 7 on B (because I really nailed the text type, I think).

My Reading List

- Name First Last

- Tell us what you think! * We welcome your feedback, constructive criticism, and/or error reports.

- Email Please enter your email if you require follow-up or would like to stay in touch.

Creative Response Exercise

Creative responses to literary works offer an opportunity to engage with the original in ways that shift our perspective from that of the critic to that of the artist, promoting alternative ways of thinking through that work.

Interacting with other works in a creative response makes the result into an intertextual text. This type of textual engagement can consist of subtle allusions or interact more obviously through borrowed content; since scholarly articles quote many other texts, they are also intertextual documents.

Intertextuality offers a way of tracing overt creative influences, but more importantly, for creators it is a strategy for affirming, adding, amending, or condemning the content of other works. Thus, the construction of one text out of others offers a creative, critical, and even political engagement with these source texts.

Write a Creative Response

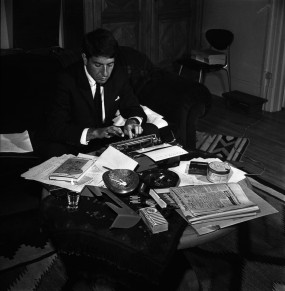

Leonard Cohen at his typewriter in Montreal, 26 October 1963. Allan R. Leishman, Montreal Star, Library and Archives Canada: accession no. 1980-108 NPC, PA-190166

Choose a poem or another piece of writing from this guide, CanLit Poets , or elsewhere in Canadian Literature , and write a creative response to it. This response can come in any literary or artistic form, but must relate to the original text in a meaningful way. Consider writing an alternate perspective on the same topic, adding further content to emphasize other connections, remediating it (i.e., changing its form, for example, into an artwork, comic, or video), or cutting and pasting it into other contexts. Come up with another revisionist approach if you like.

Critical Reflection

With this creative response in hand, now write a short, critical reflection that addresses the following:

- What do you feel you’ve accomplished in your creative response? If you had a specific aim, discuss it, the decisions you made in writing it, and why you feel it was helpful. If you were less intentional in your engagement, but had a more spontaneous response, discuss the outcome and your creative processes.

- What did you learn about the original text to which you responded? How did a creative engagement add to your understanding of the original? Be as specific as possible about what you’ve done and what it accomplishes.

First Published: Aug 15, 2013 | Last Revised: September 20, 2016

Click and drag to reorder items.

Items = 0 reset

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

4.2: Response Writing

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 6242

- Amber Kinonen, Jennifer McCann, Todd McCann, & Erica Mead

- Bay College Library

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

A response is a commentary on another piece of writing. Developing a response will help you make personal connections with the ideas in the essay. Instructors might use question prompts to help guide you in creating a focused response on a particular aspect of an assigned reading. Using a focusing question may help you stay on track and prevent the potentially frustrating and superficial task of trying to respond to everything in the essay in just one or two pages.

The summary captures only the author’s ideas; however, the response includes your own. The response is the place for your opinions, interpretations, and evaluations. The most important aspect of writing a response is to create a main idea/statement (it may be your nutshell answer to an assigned focusing question) and back it up with specific evidence. Depending on the focus of the response, it might include observations about the writer’s technique, commentary on tone or literary strategy, views as to effectiveness of the writing, relationships between the author’s ideas and your own, an analysis of content, or any number of items. If a focusing question is required, make sure the entire response directly connects to (somehow serves to answer/support the answer) the focusing question.

If you use verbatim (word-for-word) material from the essay or article, be sure it is accurate and enclose it with quotation marks. This tells the reader that you are using the author’s exacts words, not your own, and gives credit to the author. However, in this type of writing, use quotations sparingly, and try to keep them short.

How to Write a Response Paper

- Writing Essays

- Writing Research Papers

- English Grammar

- M.Ed., Education Administration, University of Georgia

- B.A., History, Armstrong State University

Most of the time when you are tasked with an essay about a book or article you've read for a class, you will be expected to write in a professional and impersonal voice. But the regular rules change a bit when you write a response paper.

A response (or reaction) paper differs from the formal review primarily in that it is written in the first person . Unlike in more formal writing, the use of phrases like "I thought" and "I believe" is encouraged in a response paper.

You'll still have a thesis and will need to back up your opinion with evidence from the work, but this type of paper spotlights your individual reaction as a reader or viewer.

Read and Respond

Grace Fleming

For a response paper, you still need to write a formal assessment of the work you're observing (this could be anything created, such as a film, a work of art, a piece of music, a speech, a marketing campaign, or a written work), but you will also add your own personal reaction and impressions to the report.

The steps for completing a reaction or response paper are:

- Observe or read the piece for an initial understanding.

- Mark interesting pages with a sticky flag or take notes on the piece to capture your first impressions.

- Reread the marked pieces and your notes and stop to reflect often.

- Record your thoughts.

- Develop a thesis.

- Write an outline.

- Construct your essay.

It may be helpful to imagine yourself watching a movie review as you're preparing your outline. You will use the same framework for your response paper: a summary of the work with several of your own thoughts and assessments mixed in.

The First Paragraph

After you have established an outline for your paper, you need to craft the first draft of the essay using all the basic elements found in any strong paper, including a strong introductory sentence .

In the case of a reaction essay, the first sentence should contain both the title of the work to which you are responding and the name of the author.

The last sentence of your introductory paragraph should contain a thesis statement . That statement will make your overall opinion very clear.

Stating Your Opinion

There's no need to feel shy about expressing your own opinion in a position paper, even though it may seem strange to write "I feel" or "I believe" in an essay.

In the sample here, the writer analyzes and compares the plays but also manages to express personal reactions. There's a balance struck between discussing and critiquing the work (and its successful or unsuccessful execution) and expressing a reaction to it.

Sample Statements

When writing a response essay, you can include statements like the following:

- I felt that

- In my opinion

- The reader can conclude that

- The author seems to

- I did not like

- This aspect didn't work for me because

- The images seemed to

- The author was [was not] successful in making me feel

- I was especially moved by

- I didn't understand the connection between

- It was clear that the artist was trying to

- The soundtrack seemed too

- My favorite part was...because

Tip : A common mistake in personal essays it to resort to insulting comments with no clear explanation or analysis. It's OK to critique the work you are responding to, but you still need to back up your feelings, thoughts, opinions, and reactions with concrete evidence and examples from the work. What prompted the reaction in you, how, and why? What didn't reach you and why?

- How To Write an Essay

- How to Write a Solid Thesis Statement

- What Is a Critique in Composition?

- Writing an Opinion Essay

- 6 Steps to Writing the Perfect Personal Essay

- 5 Steps to Writing a Position Paper

- 10 Steps to Writing a Successful Book Report

- How to Write a Great Process Essay

- How to Write a Good Thesis Statement

- How to Write a Persuasive Essay

- How to Write a News Article That's Effective

- What an Essay Is and How to Write One

- How to Write a Critical Essay

- How To Write a Top-Scoring ACT Essay for the Enhanced Writing Test

- Tips on How to Write an Argumentative Essay

- How to Write a Great Book Report

Places on our 2024 summer school are filling fast. Don’t miss out. Enrol now to avoid disappointment

- What Is Creative Writing? The ULTIMATE Guide!

At Oxford Royale Academy, we offer a range of summer school programmes that have become extremely popular amongst students of all ages. The subject of creative writing continues to intrigue many academics as it can help to develop a range of skills that will benefit you throughout your career and life.

Nevertheless, that initial question is one that continues to linger and be asked time and time again: what is creative writing? More specifically, what does it mean or encompass? How does creative writing differ from other styles of writing?

During our Oxford Summer School programme , we will provide you with in-depth an immersive educational experience on campus in the colleges of the best university in the world. However, in this guide, we want to provide a detailed analysis of everything to do with creative writing, helping you understand more about what it is and why it could benefit you to become a creative writer.

The best place to start is with a definition.

What is creative writing?

The dictionary definition of creative writing is that it is original writing that expresses ideas and thoughts in an imaginative way. [1] Some academics will also define it as the art of making things up, but both of these definitions are too simplistic in the grand scheme of things.

It’s challenging to settle on a concrete definition as creative writing can relate to so many different things and formats. Naturally, as the name suggests, it is all built around the idea of being creative or imaginative. It’s to do with using your brain and your own thoughts to create writing that goes outside the realms of what’s expected. This type of writing tends to be more unique as it comes from a personal place. Each individual has their own level of creativity, combined with their own thoughts and views on different things. Therefore, you can conjure up your own text and stories that could be completely different from others.

Understanding creative writing can be challenging when viewed on its own. Consequently, the best way to truly understand this medium is by exploring the other main forms of writing. From here, we can compare and contrast them with the art of creative writing, making it easier to find a definition or separate this form of writing from others.

What are the main forms of writing?

In modern society, we can identify five main types of writing styles [1] that will be used throughout daily life and a plethora of careers:

- Narrative Writing

- Descriptive Writing

- Persuasive Writing

- Expository Writing

- Creative Writing

Narrative writing refers to storytelling in its most basic form. Traditionally, this involves telling a story about a character and walking the readers through the journey they go on. It can be a long novel or a short story that’s only a few hundred words long. There are no rules on length, and it can be completely true or a work of fiction.

A fundamental aspect of narrative writing that makes it different from other forms is that it should includes the key elements of storytelling. As per UX Planet, there are seven core elements of a good story or narrative [2] : the plot, characters, theme, dialogue, melody, decor and spectacle. Narrative writing will include all of these elements to take the ready on a journey that starts at the beginning, has a middle point, but always comes to a conclusion. This style of writing is typically used when writing stories, presenting anecdotes about your life, creating presentations or speeches and for some academic essays.

Descriptive writing, on the other hand, is more focused on the details. When this type of writing is used, it’s focused on capturing the reader’s attention and making them feel like they are part of the story. You want them to live and feel every element of a scene, so they can close their eyes and be whisked away to whatever place or setting you describe.

In many ways, descriptive writing is writing as an art form. Good writers can be given a blank canvas, using their words to paint a picture for the audience. There’s a firm focus on the five senses all humans have; sight, smell, touch, sound and taste. Descriptive writing touches on all of these senses to tell the reader everything they need to know and imagine about a particular scene.

This is also a style of writing that makes good use of both similes and metaphors. A simile is used to describe something as something else, while a metaphor is used to show that something is something else. There’s a subtle difference between the two, but they both aid descriptive writing immensely. According to many writing experts, similes and metaphors allow an author to emphasise, exaggerate, and add interest to a story to create a more vivid picture for the reader [3] .

Looking at persuasive writing and we have a form of writing that’s all about making yourself heard. You have an opinion that you want to get across to the reader, convincing them of it. The key is to persuade others to think differently, often helping them broaden their mind or see things from another point of view. This is often confused with something called opinionative writing, which is all about providing your opinions. While the two seem similar, the key difference is that persuasive writing is built around the idea of submitting evidence and backing your thoughts up. It’s not as simple as stating your opinion for other to read; no, you want to persuade them that your thoughts are worth listening to and perhaps worth acting on.

This style of writing is commonly used journalistically in news articles and other pieces designed to shine a light on certain issues or opinions. It is also typically backed up with statistical evidence to give more weight to your opinions and can be a very technical form of writing that’s not overly emotional.

Expository writing is more focused on teaching readers new things. If we look at its name, we can take the word exposure from it. According to Merriam-Webster [4] , one of the many definitions of exposure is to reveal something to others or present them with something they otherwise didn’t know. In terms of writing, it can refer to the act of revealing new information to others or exposing them to new ideas.

Effectively, expository writing focuses on the goal of leaving the reader with new knowledge of a certain topic or subject. Again, it is predominately seen in journalistic formats, such as explainer articles or ‘how-to’ blogs. Furthermore, you also come across it in academic textbooks or business writing.

This brings us back to the centre of attention for this guide: what is creative writing?

Interestingly, creative writing is often seen as the style of writing that combines many of these forms together in one go. Narrative writing can be seen as creative writing as you are coming up with a story to keep readers engaged, telling a tale for them to enjoy or learn from. Descriptive writing is very much a key part of creative writing as you are using your imagination and creative skills to come up with detailed descriptions that transport the reader out of their home and into a different place.

Creative writing can even use persuasive writing styles in some formats. Many writers will combine persuasive writing with a narrative structure to come up with a creative way of telling a story to educate readers and provide new opinions for them to view or be convinced of. Expository writing can also be involved here, using creativity and your imagination to answer questions or provide advice to the reader.

Essentially, creative writing can combine other writing types to create a unique and new way of telling a story or producing content. At the same time, it can include absolutely none of the other forms at all. The whole purpose of creative writing is to think outside the box and stray from traditional structures and norms. Fundamentally, we can say there are no real rules when it comes to creative writing, which is what makes it different from the other writing styles discussed above.

What is the purpose of creative writing?

Another way to understand and explore the idea of creative writing is to look at its purpose. What is the aim of most creative works of writing? What do they hope to provide the reader with?

We can look at the words of Bryanna Licciardi, an experienced creative writing tutor, to understand the purpose of creative writing. She writes that the primary purpose is to entertain and share human experiences, like love or loss. Writers attempt to reveal the truth with regard to humanity through poetics and storytelling. [5] She also goes on to add that the first step of creative writing is to use one’s imagination.

When students sign up to our creative writing courses, we will teach them how to write with this purpose. Your goal is to create stories or writing for readers that entertain them while also providing information that can have an impact on their lives. It’s about influencing readers through creative storytelling that calls upon your imagination and uses the thoughts inside your head. The deeper you dive into the art of creative writing, the more complex it can be. This is largely because it can be expressed in so many different formats. When you think of creative writing, your instinct takes you to stories and novels. Indeed, these are both key forms of creative writing that we see all the time. However, there are many other forms of creative writing that are expressed throughout the world.

What are the different forms of creative writing?

Looking back at the original and simple definition of creative writing, it relates to original writing in a creative and imaginative way. Consequently, this can span across so many genres and types of writing that differ greatly from one another. This section will explore and analyse the different types of creative writing, displaying just how diverse this writing style can be – while also showcasing just what you’re capable of when you learn how to be a creative writer.

The majority of students will first come across creative writing in the form of essays . The point of an essay is to present a coherent argument in response to a stimulus or question. [6] In essence, you are persuading the reader that your answer to the question is correct. Thus, creative writing is required to get your point across as coherently as possible, while also using great descriptive writing skills to paint the right message for the reader.