An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Heart Views

- v.18(3); Jul-Sep 2017

Guidelines To Writing A Clinical Case Report

What is a clinical case report.

A case report is a detailed report of the symptoms, signs, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of an individual patient. Case reports usually describe an unusual or novel occurrence and as such, remain one of the cornerstones of medical progress and provide many new ideas in medicine. Some reports contain an extensive review of the relevant literature on the topic. The case report is a rapid short communication between busy clinicians who may not have time or resources to conduct large scale research.

WHAT ARE THE REASONS FOR PUBLISHING A CASE REPORT?

The most common reasons for publishing a case are the following: 1) an unexpected association between diseases or symptoms; 2) an unexpected event in the course observing or treating a patient; 3) findings that shed new light on the possible pathogenesis of a disease or an adverse effect; 4) unique or rare features of a disease; 5) unique therapeutic approaches; variation of anatomical structures.

Most journals publish case reports that deal with one or more of the following:

- Unusual observations

- Adverse response to therapies

- Unusual combination of conditions leading to confusion

- Illustration of a new theory

- Question regarding a current theory

- Personal impact.

STRUCTURE OF A CASE REPORT[ 1 , 2 ]

Different journals have slightly different formats for case reports. It is always a good idea to read some of the target jiurnals case reports to get a general idea of the sequence and format.

In general, all case reports include the following components: an abstract, an introduction, a case, and a discussion. Some journals might require literature review.

The abstract should summarize the case, the problem it addresses, and the message it conveys. Abstracts of case studies are usually very short, preferably not more than 150 words.

Introduction

The introduction gives a brief overview of the problem that the case addresses, citing relevant literature where necessary. The introduction generally ends with a single sentence describing the patient and the basic condition that he or she is suffering from.

This section provides the details of the case in the following order:

- Patient description

- Case history

- Physical examination results

- Results of pathological tests and other investigations

- Treatment plan

- Expected outcome of the treatment plan

- Actual outcome.

The author should ensure that all the relevant details are included and unnecessary ones excluded.

This is the most important part of the case report; the part that will convince the journal that the case is publication worthy. This section should start by expanding on what has been said in the introduction, focusing on why the case is noteworthy and the problem that it addresses.

This is followed by a summary of the existing literature on the topic. (If the journal specifies a separate section on literature review, it should be added before the Discussion). This part describes the existing theories and research findings on the key issue in the patient's condition. The review should narrow down to the source of confusion or the main challenge in the case.

Finally, the case report should be connected to the existing literature, mentioning the message that the case conveys. The author should explain whether this corroborates with or detracts from current beliefs about the problem and how this evidence can add value to future clinical practice.

A case report ends with a conclusion or with summary points, depending on the journal's specified format. This section should briefly give readers the key points covered in the case report. Here, the author can give suggestions and recommendations to clinicians, teachers, or researchers. Some journals do not want a separate section for the conclusion: it can then be the concluding paragraph of the Discussion section.

Notes on patient consent

Informed consent in an ethical requirement for most studies involving humans, so before you start writing your case report, take a written consent from the patient as all journals require that you provide it at the time of manuscript submission. In case the patient is a minor, parental consent is required. For adults who are unable to consent to investigation or treatment, consent of closest family members is required.

Patient anonymity is also an important requirement. Remember not to disclose any information that might reveal the identity of the patient. You need to be particularly careful with pictures, and ensure that pictures of the affected area do not reveal the identity of the patient.

Case Reports: How to Write a Case Report

- How to Write a Case Report

- Case Report Resources

- YouTube Resources

Consensus-Based Clinical Case Reporting Guidelines

| This was developed by to correspond with key components of a case report and capture useful clinical information (including 'meaningful use' information mandated by some insurance plans). The narrative: A case report tells a story in a narrative format that includes the presenting concerns, clinical findings, diagnoses, interventions, outcomes (including adverse events), and follow-up. The narrative should include a discussion of the rationale for any conclusions and any take-away messages. |

| Title | 1 | The words "case report: should be in the title, along with area of focus |

| Keywords | 2 | Four to seven keywords - include "case report" as one of the keywords |

| Abstract | 3a | Background: What does this case report add to the medical literature? |

| 3b | Case summary: chief complaint, diagnoses, interventions, and outcomes | |

| 3c | Conclusion: What is the main "take-away" lesson from this case? | |

| Introduction | 4 | The current standard of care and contributions of this case - with references (1-2 paragraphs) |

| Timeline | 5 | Information from this case report organized into a timelines (table or figure) |

| Patient Information | 6a | De-identified demographic and other patient or client specific information |

| 6b | Chief complaint - what prompted the visit? | |

| 6c | Relevant history including past interventions and outcomes | |

| Physical Exam | 7 | Relevant physical examination findings |

| Diagnostic Assessment | 8a | Evaluations such as surveys, laboratory testing, imaging, etc. |

| 8b | Diagnostic reasoning including other diagnoses considered and challenges | |

| 8c | Consider tables or figures linking assessment, diagnoses, and interventions | |

| 8d | Prognostic characteristics where applicable | |

| Interventions | 9a | Types such as lifestyle recommendations, treatments, medications, surgery |

| 9b | Intervention administration such as dosage, frequency, and duration | |

| 9c | Note changes in intervention with explanation | |

| 9d | Other concurrent interventions | |

| Follow-up and Outcomes | 10a | Clinician assessment (and patient or client assessed outcomes when appropriate) |

| 10b | Important follow-up diagnostic evaluations | |

| 10c | Assessment of intervention adherence and tolerability, including adverse events | |

| Discussion | 11a | Strengths and limitations in your approach to the case |

| 11b | Specify how this case report informs practice or Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPG) | |

| 11c | How does this case report suggest a testable hypothesis? | |

| 11d | Conclusions and rationale | |

| Patient Perspective | 12 | When appropriate, include the assessment of the patient or client on this episode of care |

| Informed Consent | 13 | Informed consent from the person who is the subject of this case report, required by most journals |

| Additional Information | 14 | Acknowledgement section; Competing Interests; IRB approval when required |

Gagnier JJ, Riley D, Altman DG, Moher D, Sox H, Kienle GS, for the CARE group: The CARE guidelines: Consensus-based clinical case reporting guideline development. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2013; 110(37): 603-8.

Select Journals Accepting Case Reports

| The following journals are indexed in Medline and currently accepting case reports (as of 12/2/2016) either regularly or under specific circumstances. Click on the links below to view the author instructions for each journal and determine if your case meets the journal's criteria. |

Case Report Templates

The CAse REporting (CARE) team created templates in nine languages to assist clinicians, researchers, and educators with the ultimate goal of improving the completeness, transparency, and usefulness of case reports.

English , Spanish , German , Chinese , Dutch , French , Japanese , Korean , Portuguese

- Case Report Journals

A list of case report journals can be found in the pdf below. It provides information on the year launched, open-access status, reported questionable publishing practices, and whether the journal is indexed in Medline. The majority of these journals are open-access and will require a submission fee.

BMJ Case Reports

- BMJ Consent Form

The Library has an institutional fellowship with BMJ Case Reports which allows faculty, staff, and students at Weill Cornell Medicine to submit case reports without paying an individual fellowship fee. Use our fellowship code when you are ready to publish.

Please note: BMJ Case Reports, like most journals, requires a signed consent form in order for a case report to be considered for publication.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Case Report Resources >>

- Last Updated: Aug 15, 2022 12:15 PM

- URL: https://med.cornell.libguides.com/casereports

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 30 January 2023

A student guide to writing a case report

- Maeve McAllister 1

BDJ Student volume 30 , pages 12–13 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

26 Accesses

Metrics details

As a student, it can be hard to know where to start when reading or writing a clinical case report either for university or out of special interest in a Journal. I have collated five top tips for writing an insightful and relevant case report.

A case report is a structured report of the clinical process of a patient's diagnostic pathway, including symptoms, signs, diagnosis, treatment planning (short and long term), clinical outcomes and follow-up. 1 Some of these case reports can sometimes have simple titles, to the more unusual, for example, 'Oral Tuberculosis', 'The escapee wisdom tooth', 'A difficult diagnosis'. They normally begin with the word 'Sir' and follow an introduction from this.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

We are sorry, but there is no personal subscription option available for your country.

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Guidelines To Writing a Clinical Case Report. Heart Views 2017; 18 , 104-105.

British Dental Journal. Case reports. Available online at: www.nature.com/bdj/articles?searchType=journalSearch&sort=PubDate&type=case-report&page=2 (accessed August 17, 2022).

Chate R, Chate C. Achenbach's syndrome. Br Dent J 2021; 231: 147.

Abdulgani A, Muhamad, A-H and Watted N. Dental case report for publication; step by step. J Dent Med Sci 2014; 3 : 94-100.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Queen´s University Belfast, Belfast, United Kingdom

Maeve McAllister

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Maeve McAllister .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

McAllister, M. A student guide to writing a case report. BDJ Student 30 , 12–13 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41406-023-0925-y

Download citation

Published : 30 January 2023

Issue Date : 30 January 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41406-023-0925-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Writing a Case Report

This page is intended for medical students, residents or others who do not have much experience with case reports, but are planning on writing one.

What is a case report? A medical case report, also known as a case study, is a detailed description of a clinical encounter with a patient. The most important aspect of a case report, i.e. the reason you would go to the trouble of writing one, is that the case is sufficiently unique, rare or interesting such that other medical professionals will learn something from it.

Case reports are commonly of the following categories :

- Rare diseases

- Unusual presentation of disease

- Unexpected events

- Unusual combination of diseases or conditions

- Difficult or inconclusive diagnosis

- Treatment or management challenges

- Personal impact

- Observations that shed new light on a disease or condition

- Anatomical variations

It is important that you recognize what is unique or interesting about your case, and this must be described clearly in the case report.

Case reports generally take the format of :

1. Background

2. Case presentation

3. Observations and investigation

4. Diagnosis

5. Treatment

7. Discussion

Does a case report require IRB approval?

Case reports typically discuss a single patient. If this is true for your case report, then it most likely does not require IRB approval because it not considered research. If you have more than one patient, your study could qualify as a Case Series, which would require IRB review. If you have questions, you chould check your local IRB's guidelines on reviewing case reports.

Are there other rules for writing a case report?

First, you will be collecting protected health information, thus HIPAA applies to case reports. Spectrum Health has created a very helpful guidance document for case reports, which you can see here: Case Report Guidance - Spectrum Health

While this guidance document was created by Spectrum Health, the rules and regulations outlined could apply to any case report. This includes answering questions like: Do I need written HIPAA authorization to publish a case report? When do I need IRB review of a case report? What qualifies as a patient identifier?

How do I get started?

1. We STRONGLY encourage you to consult the CARE Guidelines, which provide guidance on writing case reports - https://www.care-statement.org/

Specifically, the checklist - https://www.care-statement.org/checklist - which explains exactly the information you should collect and include in your case report.

2. Identify a case. If you are a medical student, you may not yet have the clinical expertise to determine if a specific case is worth writing up. If so, you must seek the help of a clinician. It is common for students to ask attendings or residents if they have any interesting cases that can be used for a case report.

3. Select a journal or two to which you think you will submit the case report. Journals often have specific requirements for publishing case reports, which could include a requirement for informed consent, a letter or statement from the IRB and other things. Journals may also charge publication fees (see Is it free to publish? below)

4. Obtain informed consent from the patient (see " Do I have to obtain informed consent from the patient? " below). Journals may have their own informed consent form that they would like you to use, so please look for this when selecting a journal.

Once you've identified the case, selected an appropriate journal(s), and considered informed consent, you can collect the required information to write the case report.

How do I write a case report?

Once you identify a case and have learned what information to include in the case report, try to find a previously published case report. Finding published case reports in a similar field will provide examples to guide you through the process of writing a case report.

One journal you can consult is BMJ Case Reports . MSU has an institutional fellowship with BMJ Case Reports which allows MSU faculty, staff and students to publish in this journal for free. See this page for a link to the journal and more information on publishing- https://lib.msu.edu/medicalwriting_publishing/

There are numerous other journals where you can find published case reports to help guide you in your writing.

Do I have to obtain informed consent from the patient?

The CARE guidelines recommend obtaining informed consent from patients for all case reports. Our recommendation is to obtain informed consent from the patient. Although not technically required, especially if the case report does not include any identifying information, some journals require informed consent for all case reports before publishing. The CARE guidelines recommend obtaining informed consent AND the patient's perspective on the treatment/outcome (if possible). Please consider this as well.

If required, it is recommended you obtain informed consent before the case report is written.

An example of a case report consent form can be found on the BMJ Case Reports website, which you can access via the MSU library page - https://casereports.bmj.com/ . Go to "Instructions for Authors" and then "Patient Consent" to find the consent form they use. You can create a similar form to obtain consent from your patient. If you have identified a journal already, please consult their requirements and determine if they have a specific consent form they would like you to use.

Seek feedback

Once you have written a draft of the case report, you should seek feedback on your writing, from experts in the field if possible, or from those who have written case reports before.

Selecting a journal

Aside from BMJ Case Reports mentioned above, there are many, many journals out there who publish medical case reports. Ask your mentor if they have a journal they would like to use. If you need to select on your own, here are some strategies:

1. Do a PubMed search. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

a. Do a search for a topic, disease or other feature of your case report

b. When the results appear, on the left side of the page is a limiter for "article type". Case reports are an article type to which you can limit your search results. If you don't see that option on the left, click "additional filters".

c. Review the case reports that come up and see what journals they are published in.

2. Use JANE - https://jane.biosemantics.org/

3. Check with specialty societies. Many specialty societies are affiliated with one or more journal, which can be reviewed for ones that match your needs

4. Search through individual publisher journal lists. Elsevier publishes many different medical research journals, and they have a journal finder, much like JANE ( https://journalfinder.elsevier.com/ ). This is exclusive to Elsevier journals. There are many other publishers of medical journals for review, including Springer, Dove Press, BMJ, BMC, Wiley, Sage, Nature and many others.

Is it free to publish ?

Be aware that it may not be free to publish your case report. Many journals charge publication fees. Of note, many open access journals charge author fees of thousands of dollars. Other journals have smaller page charges (i.e. $60 per page), and still others will publish for free, with an "open access option". It is best practice to check the journal's Info for Authors section or Author Center to determine what the cost is to publish. MSU-CHM does NOT have funds to support publication costs, so this is an important step if you do not want to pay out of pocket for publishing

*A more thorough discussion on finding a journal, publication costs, predatory journals and other publication-related issues can be found here: https://research.chm.msu.edu/students-residents/finding-a-journal

Gagnier JJ, Kienle G, Altman DG, Moher D, Sox H, Riley D. 2013. The CARE guidelines: Consensus-based clinical case reporting guideline development. Glob Adv Health Med . 2:38-43. doi: 10.7453/gahmj.2013.008

Riley DS, Barber MS, Kienle GS, AronsonJK, von Schoen-Angerer T, Tugwell P, Kiene H, Helfand M, Altman DG, Sox H, Werthmann PG, Moher D, Rison RA, Shamseer L, Koch CA, Sun GH, Hanaway P, Sudak NL, Kaszkin-Bettag M, Carpenter JE, Gagnier JJ. 2017. CARE guidelines for case reports: explanation and elaboration document . J Clin Epidemiol . 89:218-234. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.04.026

Guidelines to writing a clinical case report. 2017. Heart Views . 18:104-105. doi: 10.4103/1995-705X.217857

Ortega-Loubon C, Culquichicon C, Correa R. The importance of writing and publishing case reports during medical education. 2017. Cureus. 9:e1964. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1964

Writing and publishing a useful and interesting case report. 2019. BMJ Case Reports. https://casereports.bmj.com/pages/wp-content/uploads/sites/69/2019/04/How-to-write-a-Case-Report-DIGITAL.pdf

Camm CF. Writing an excellent case report: EHJ Case Reports , Case of the Year 2019. 2020. European Heart Jounrnal. 41:1230-1231. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa176

*content developed by Mark Trottier, PhD

How to Write a Case Report

- First Online: 01 January 2020

Cite this chapter

- Richard Balon 2 &

- Eugene V. Beresin 3 , 4 , 5

1398 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Case reports are an important starting point for academic writing and for producing new, interesting, and educational information for the field. They usually describe a unique syndrome or disease, an unexpected relationship between relatively uncommon diseases or symptoms, unique or rare events or outcomes in describing a disease, or a unique therapeutic approach to an illness. Authors should not write a case report simply for the sake of writing. Rather, the case report must help improve understanding of a disease or improve therapy. Thus, detailed preparation is crucial, including a thorough literature search about the disease, treatment, and outcomes. A single outlying case or freak episode may unintentionally negatively influence some clinical practice. Hence, authors must remember that there is a great professional responsibility in providing a case report. Patient privacy must be preserved. All identifying information should be omitted unless essential for scientific purposes, and informed consent is often required. The structure of the case report should include the Title/Title page; Abstract (summary of the case) (only if required by the journal); Introduction (purpose, worthiness of the case, based on references); Case Description (most salient parts of the case and its outcome); Discussion/Conclusion (presents the broad view of the case, its uniqueness, and contribution to the literature); at times Patient’s Perspective; Acknowledgments; and References.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The Historical Tradition of Case Reporting

How to Write a Case Report?

Borus JF. Writing for publication. In: Kay J, Silberman EK, Pessar L, editors. Handbook of psychiatric education and faculty development. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press; 1999. p. 57–93.

Google Scholar

Schnur D, Cheruvanki B, Mustafa R. The case report: a user-friendly educational tool for psychiatry residency programs. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40:857–8.

Article Google Scholar

Martyn C. Case reports, case series and systematic reviews. Q J Med. 2002;95:197–8.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Akers KG. New journals for publishing medical case reports. J Med Libr Assoc. 2016;104:146–9.

Rison RA. A guide to writing case reports for the journal of medical case reports and BioMed central research notes. J Med Cas Rep. 2013;7:239. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1947-7-239 .

Roselli D, Otero A. The case report is far from dead. Lancet. 2002;359:84.

Gagnier JJ, Kienle G, Altman DG, Moher D, Sox H, Riley D, the CARE Group. The CARE guidelines: consensus –based clinical case reporting guideline development. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013201554. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2013-201554.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Riley DS, Barber MS, Kienle GS, Aronson JK, von Schoen-Angerer T, Tugwell P, et al. CARE guidelines for case reports: explanation and elaboration document. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;89:218–35.

Green BN, Johnson CD. How to write a case report for publication. J Chiropr Med. 2006;5:72–82.

Iles RL, Piepho RW. Presenting and publishing case reports. J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;36:573–9.

Wright SM, Kouroukis C. Capturing zebras: what to do with a reportable case. Can Med Assoc J. 2000;163:429–31.

CAS Google Scholar

Procopio M. Publication of case reports. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:91.

DeBakey L, DeBakey S. The case report. I. Guidelines for preparation. Int J Cardiol. 1983;4:357–64.

Sorinola O, Loufowobi O, Coomarasamy A, Khan KS. Instructions to authors for case reporting are limited: a review of a core journal list. BMC Med Educ. 2004;4:4.

Rison RA, Shepphird JK, Kidd MR. How to choose the best journal for your case report. J Med Cas Rep. 2017;11:198. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-017-1351-y .

Beall J. Best practices for scholarly authors in the age of predatory journals. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2016;98:77–8.

Beall J. Dangerous predatory publishers threaten medical research. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31:1511–3.

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Protection of patients’ rights to privacy. BMJ. 1995;311:1272.

Singer PA. Consent to publication of patient information. BMJ. 2004;329:566–8.

Levine SB, Stagno SJ. Informed consent for case reports. The ethical dilemma of right to privacy versus pedagogical freedom. J Psychother Pract Res. 2001;10:193–201.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Har-El G. Does it take a village to write a case report? Otolaryng Head Neck Surg. 1999;120:787–8.

McCarthy LH, Reilly KEH. How to write a case report. Fam Med. 2000;32:190–5.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Squires BP. Case reports: what editors want from authors and peer reviewers. Can Med Assoc J. 1989;141:379–80.

Chelvarajah R, Bycroft J. Writing and publishing case reports: to road to success. Acta Neurochir. 2004;146:313–6.

Cohen H. How to write a patient case report. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63:1888–92.

DeBakey L, DeBakey S. The case report. II. Style and form. Int J Cardiol. 1984;6:247–54.

Resnik PJ, Soliman S. Draftsmanship. In: Buchanan A, Norco MA, editors. The psychiatric report. Principles and practice of forensic writing. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2011. p. 81–92.

Chapter Google Scholar

Suggested Reading

Huth FJ. Writing and publishing in medicine. 3rd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1999.. (previously published as How to write and publish papers in medical sciences )

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Departments of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences and Anesthesiology, Wayne State University, and Detroit Medical Center, Detroit, MI, USA

Richard Balon

Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

Eugene V. Beresin

The Clay Center for Young Healthy Minds, Boston, MA, USA

Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Richard Balon .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA

Laura Weiss Roberts

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Balon, R., Beresin, E.V. (2020). How to Write a Case Report. In: Roberts, L. (eds) Roberts Academic Medicine Handbook. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-31957-1_30

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-31957-1_30

Published : 01 January 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-31956-4

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-31957-1

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Get new issue alerts Get alerts

- Submit a Manuscript

Secondary Logo

Journal logo.

Colleague's E-mail is Invalid

Your message has been successfully sent to your colleague.

Save my selection

How to Write Case Reports and Case Series

Ganesan, Prasanth

Department of Medical Oncology, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research, Puducherry, India

Address for correspondence: Dr. Prasanth Ganesan, Medical Oncology, 3 rd Floor, SSB, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research, Dhanvantari Nagar, Puducherry - 605006, India. E-mail: [email protected]

Received March 13, 2022

Received in revised form April 10, 2022

Accepted April 10, 2022

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

Case reports are considered the smallest units of descriptive studies. They serve an important function in bringing out information regarding presentation, management, and/or outcomes of rare diseases. They can also be a starting point in understanding unique associations in clinical medicine and can introduce very effective treatment paradigms. Preparing the manuscript for a case report may be the first exposure to scientific writing for a budding clinician/researcher. This manuscript describes the steps of writing a case report and essential considerations when publishing these articles. Individual components of a case report and the “dos and don'ts” while preparing these components are detailed.

INTRODUCTION

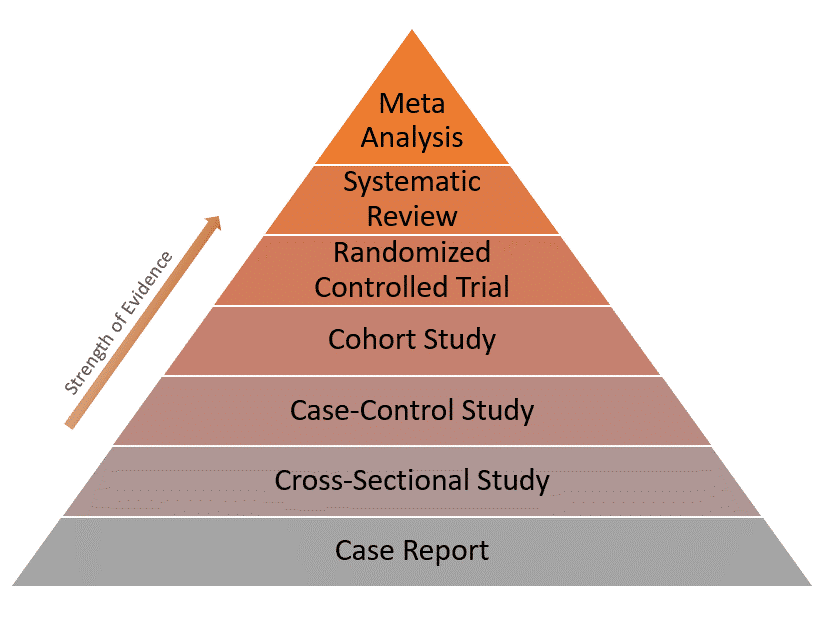

A case report describes several aspects of an individual patient's presentation, investigations, management decisions, and/or outcomes. This is a type of observational study and has been described as the smallest publishable unit in medical literature.[ 1 ] A case series involves a group of patients with similar presentations or treatments. In modern medicine [ Figure 1 ], these publications are categorized as the “lowest level of evidence”.[ 2 ] However, they serve several essential functions. For example, there are rare diseases where large, randomized trials, or even observational studies may not be possible. Medical practice, in these conditions, is often guided by well-presented case reports or series. There are situations where a single case report has heralded an important therapy change.[ 3 ] Further, case reports are often a student's first exposure to manuscript writing. Hence, these serve as training for budding scholars to understand scientific writing, learn the process of manuscript submission, and receive and respond to reviewer comments. This article explains the reasons why case reports are published and provides guidance for writing such type of articles.

WHY ARE CASE REPORTS PUBLISHED?

A case report is often published to highlight the rarity of a particular presentation. However, it may be of much more value if it also informs some aspects of management. This could be in the form of rare expressions of a common disease so that clinicians who read will be aware and can consider additional possibilities and differential diagnoses when encountering similar situations. A new form of evaluation of a patient, either to facilitate the diagnostics or to improve understanding of the disease condition, may stimulate a case report. Novel treatments may be tried, and the results might be necessary to disseminate. This may be encountered either in rare diseases or conditions where treatment options are exhausted. Moreover, randomized trials report outcomes of a group and often do not inform about the individual patient. [ Table 1 ] describes a few examples of case reports/case series which have had a remarkable impact on medical practice.

ETHICAL ISSUES

If there is a possibility of patient identification from the report, it is mandatory to obtain informed consent from the patient while approval from the institutional ethics committee (IEC) may also be needed depending on institutional policies.[ 7 ] If identifying information is absent (or if suitable steps are taken to remove identifying information or hide the identity, (such as by covering the eyes), it may still be required by some journals to obtain ethics committee approval for certain types of case reports. If a case series involves retrospective chart review, “waiver-of-consent” may be sought from the ethics committee. Indian Ethical Guidelines do not separately address this issue in case reports.[ 8 ] The Committee on Publication Ethics has described best practices for journals when publishing case reports which also gives links to model consent forms.[ 9 ]

HOW TO START?

If you are a beginner and you have identified an interesting case which you want to report, the first step would be to sit with your team and discuss the aspects of the case you want to highlight in your publication.[ 10 ] Do a literature search and try to summarize available information before writing the draft. It would also be a good idea to understand which journal you are targeting; this will assist in determining the number of figures, the word limits, and ethical requirements (such as informed consent). Discussions with senior faculty about the authors and their order should also be done at this point to avoid issues later. For a beginner, it would be a good practice to present the case in the department or in an institutional scientific forum before writing up the manuscript.

COMPONENTS OF a CASE REPORT

A case report usually has the following sections: an abstract, a brief introduction, the actual description of the case, and finally, the discussion which highlights the uniqueness of the case and includes a conclusion statement. Many journals these days publish case reports only as a letter to editor; in such cases, an abstract is not usually required.

The title must be informative about the problem being reported. It may refer to the particular issue being highlighted in the report, or it may refer to the educational aspect of that particular report. Catchy titles are often used by authors to trigger interest among the readers and make them want to read the article. Authors may remember to use titles which will help people locate the article when searching the literature.

When writing a title, it may be best to avoid terms such as “case report,” “review of literature,” “unique,” “rare,” “first-report”; these do not add value to the presentation.

Introduction

This must introduce the condition and clearly state why the case report is worth reading. It may also contain a brief mention of the current status of the problem being described with supporting references.

Describing the case

The case must be presented succinctly, in a chronological order, clearly highlighting the salient aspects of the case being reported. Relevant negative findings may be provided. For example, if a case is being reported for elaborating a new type of treatment, then more attention must be given to treatment aspects (e.g., name of the drug, dosage, schedule, dose modifications, or the type of surgery, duration, and type of anesthesia) after briefly describing the presentation and diagnostics. The idea is that the reader must be able to apply the treatment in his/her practice if required.

However, if the case is being presented for diagnostic rarity/unusual clinical features/pathological aspects, then more attention must be given to these aspects. For example, if the emphasis is on tissue pathology, then the description must include details about tissue processing, types of stains, and immunohistochemistry details.

Figures and tables

Figures, as in any publication, should be self-explanatory. A properly constructed figure legend can be used for describing certain aspects of the case much better than long-winded text in the main manuscript. This will also help to reduce the word count in the main manuscript. If there are multiple figures (e.g., follow-up radiology series and response to treatment images), these can be combined as [ Figure 1 ]a, [ Figure 1 ]b, [ Figure 1c ] or [ Figure 1 ]a, [ Figure 1 ]b, [ Figure 1 ]c, [ Figure 1d ]. This will help conform to the figure number limits prescribed by the journal. While preparing the figures, one must ensure that the quality of the art/photograph is not compromised. Further, patient identifying features must be masked, unless necessary to show.

Tables are usually not part of case reports but may be used. One example is presenting the baseline investigations in a tabular format which can facilitate assimilation as well as reduce the word count. Tables are more often used in case series. The most common is a type of table where the features of all the cases included are summarized with each row referring to an individual patient. This usually works for a series of up to ten patients; beyond that, the table may become crowded and difficult to understand. Tables may also be used in the discussion section to summarize related, published reports to date.

Discussion including review

A case report may help to alter the approach to patient management in the clinic or it may even stimulate original research evaluating a new treatment. Thus, the discussion must summarize the unique aspects of the case (why is the case different?) and the essential learning points/implications (how will it change management?/What further research needs to be done?). In addition to stating the differences from existing literature, the discussion should also attempt to explain these differences.

If the condition or treatment approach being focused on is sufficiently rare, reviewing all available cases published until that point is critical. This review may be presented in a table with each case described briefly. A more nuanced study might attempt to summarize the relevant demographics and clinical details of the various cases published to date in the form of a table (e.g., median age, gender distribution, and survival outcomes).

CASE SERIES - WHAT IS DIFFERENT?

There is no formal definition as to what is case series and what would be considered a retrospective cohort study. In general, a case series comprises <10 cases; beyond that, it may be feasible to apply formal statistics and may be considered a cohort study.

Both case reports and case series are descriptive studies. Case series must have similar cases and hence the inclusion must be clearly defined. The interventions must be documented in a way that is reproducible and follow-up of each individual in the report must be available. Although formal statistical analyses are usually not a part of case series, authors may attempt to summarize baseline demographic parameters using descriptive statistics.

ABSTRACT OF a CASE REPORT

As explained earlier, a few journals do not require abstracts for case report submissions. When required, one should try to highlight the salient aspects of the case presented and the reason for the publication within the abstract word limit, which may be as short as 100–200 words. Spend time and effort in writing a good abstract as this is a portion which is usually read by the editor during manuscript screening and may have implications for whether the article progresses to the next stage of editorial processing.

REFERENCES IN a CASE REPORT

One may only cite key references in a case report or series as there is limited scope for elaborate literature search. Most journals have a limit of 10–15 references for case reports; when publishing as a letter to editor (or correspondence), the allowed reference limit may be even lower (five or less for some journals).

CHOOSING THE RIGHT JOURNAL

Many journals have recently stopped publishing case reports and series. This is often an attempt by journals to optimize their resources (space and reviewer time) to attain the highest possible impact. Although this is unfortunate, it is a reality which must be acknowledged. Nonetheless, the advent of online-only journals has led to more options for aspiring authors. Some journals accept case series, whereas others have “sister” journals created to accept case reports and other, less definitive, contributions to the literature.[ 11 ] It is an important exercise to study all available journals accepting case reports of the type being written. The case report must be tailored to the journal's requirements. Many journals may charge an article processing fee; author(s) must consider whether they are willing to pay and publish. Some of these may be predatory journals; authors must be wary of them and scrupulously avoid publishing in such journals as they can permanently stain the publication records of a researcher.

PUBLISHING THE CASE REPORT/SERIES AS a LETTER TO EDITOR/IMAGE SERIES

When the matter to be conveyed is very minimal or is being published mainly for its rarity, letters to editor may be an alternate route to publish case report data. Interesting images may be published in the form of “images” series which is now a part of many journals. The flexibility of web-based publishing also allows interesting videos to be published online.

GUIDELINES FOR CASE REPORTS

There are guidelines which help authors in the preparation and submission of case reports. The CAse REports (CARE) checklist is one such popular guideline. It provides a “checklist” and other resources for authors that can help navigate the process of writing a case report, especially when a person is doing it for the first time.[ 12 ]

AUTHORSHIP IN CASE REPORTS

Although there are no separate guidelines for authorship in “case reports,” general authorship rules follow that for any manuscript. “Gift” authorship must be avoided. All authors must have contributed to the creation of the manuscript in addition to being involved in some aspect of care of the patient being reported. Authorship order should be ideally predecided based on mutual consensus.

CONCLUSIONS

A case report is a useful starting point for one's scientific writing career. There are useful online resources which describe the steps for a newbie writer.[ 13 14 ] [ Table 2 ] summarizes the important components to follow and understand when writing case reports. Although many frontline journals have reduced their acceptance of case reports, these publications continue to serve an essential scientific and academic role.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

Case reports; manuscript writing; case series; references

- + Favorites

- View in Gallery

Readers Of this Article Also Read

How to revise and resubmit the manuscript after a favorable peer review, glossopharyngeal neuralgia following coronavirus disease 2019 infection, polymorphous adenocarcinoma of the parotid – an uncommon site of occurrence, primary vulval mucinous adenocarcinoma of intestinal type masquerading as..., detection of rare blood group ax phenotype in blood donor.

Case Report: A Beginner’s Guide with Examples

A case report is a descriptive study that documents an unusual clinical phenomenon in a single patient. It describes in details the patient’s history, signs, symptoms, test results, diagnosis, prognosis and treatment. It also contains a short literature review, discusses the importance of the case and how it improves the existing knowledge on the subject.

A similar design involving a group of patients (with the similar problem) is referred to as case series.

Advantages of case reports

Case reports offer, in general a fast, easy and cheap way to report an unusual observation or a rare event in a clinical setting, as these have very small probability of being detected in an experimental study because of limitations on the number of patients that can be included.

These events deserve to be reported since they might provide insights on some exceptions to general rules and theories in the field.

Case reports are great to get first impressions that can generate new hypotheses (e.g. detecting a potential side effect of a drug) or challenge existing ones (e.g. shedding the light on the possibility of a different biological mechanism of a disease).

In many of these cases, additional investigation is needed such as designing large observational studies or randomized experiments or even going back and mining data from previous research looking for evidence for theses hypotheses.

Limitations of case reports

Observing a relationship between an exposure and a disease in a case report does not mean that it is causal in nature.

This is because of:

- The absence of a control group that provides a benchmark or a point of reference against which we compare our results. A control group is important to eliminate the role of external factors which can interfere with the relationship between exposure and disease

- Unmeasured Confounding caused by variables that influence both the exposure and the disease

A case report can have a powerful emotional effect (see examples of case reports below). This can lead to overrate the importance of the evidence provided by such case. In his book Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion , Paul Bloom explains how a powerful story affects our emotions, can distort our judgement and even lead us to make bad moral choices.

When a case report describes a rare event it is important to remember that what we’re reading about is exceptional and most importantly resist generalizations especially because a case report is, by definition, a study where the sample is only 1 patient.

Selection bias is another issue as the cases in case reports are not chosen at random, therefore some members of the population may have a higher probability of being included in the study than others.

So, results from a case report cannot be representative of the entire population.

Because of these limitations, case reports have the lowest level of evidence compared to other study designs as represented in the evidence pyramid below:

Real-world examples of case reports

Example 1: normal plasma cholesterol in an 88-year-old man who eats 25 eggs a day.

This is the case of an old man with Alzheimer’s disease who has been eating 20-30 eggs every day for almost 15 years. [ Source ]

The man had an LDL-cholesterol level of only 142 mg/dL (3.68 mmol/L) and no significant clinical atherosclerosis (deposition of cholesterol in arterial walls)!

His body adapted by reducing the intestinal absorption of cholesterol, lowering the rate of its synthesis and increasing the rate of its conversion into bile acid.

This is indeed an unusual case of biological adaptation to a major change in dietary intake.

Example 2: Recovery from the passage of an iron bar through the head

This is an interesting case of a construction foreman named Phineas Gage. [ Source ]

In 1848, due to an explosion at work, an iron bar passed through his head destroying a large portion of his brain’s frontal lobe. He survived the event and the injury only affected 1 thing: His personality!

After the accident, Gage became profane, rough and disrespectful to the extent that he was no longer tolerable to people around him. So he lost his job and his family.

His case inspired further research that focused on the relationship between specific parts of the brain and personality.

- Sayre JW, Toklu HZ, Ye F, Mazza J, Yale S. Case Reports, Case Series – From Clinical Practice to Evidence-Based Medicine in Graduate Medical Education . Cureus . 2017;9(8):e1546. Published 2017 Aug 7. doi:10.7759/cureus.1546.

- Nissen T, Wynn R. The clinical case report: a review of its merits and limitations . BMC Res Notes . 2014;7:264. Published 2014 Apr 23. doi:10.1186/1756-0500-7-264.

Further reading

- Case Report vs Cross-Sectional Study

- Cohort vs Cross-Sectional Study

- How to Identify Different Types of Cohort Studies?

- Matched Pairs Design

- Randomized Block Design

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Medical Studies

How to Write a Medical Case Study Report

Last Updated: April 18, 2024 Fact Checked

This article was medically reviewed by Mark Ziats, MD, PhD and by wikiHow staff writer, Jennifer Mueller, JD . Dr. Mark Ziats is an Internal Medicine Physician, Scientist, Entrepreneur, and the Medical Director of xBiotech. With over five years of experience, he specializes in biotechnology, genomics, and medical devices. He earned a Doctor of Medicine degree from Baylor College of Medicine, a Ph.D. in Genetics from the University of Cambridge, and a BS in Biochemistry and Chemistry from Clemson University. He also completed the INNoVATE Program in Biotechnology Entrepreneurship at The Johns Hopkins University - Carey Business School. Dr. Ziats is board certified by the American Board of Internal Medicine. There are 15 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 187,526 times.

You've encountered an interesting and unusual case on your rounds, and a colleague or supervising physician says, "Why don't you write up a case study report?" If you've never written one before, that might sound intimidating, but it's a great way to get started in medical writing. Case studies always follow a standard structure and format, so the writing is very formulaic once you get the hang of it. Read on for a step-by-step guide to writing your first case study report.

What is a case study report?

- Medical students or residents typically do the bulk of the writing of the report. If you're just starting your medical career, a case study report is a great way to get a publication under your belt. [2] X Research source

- If the patient is a minor or is incapable of giving informed consent, get consent from their parents or closest relative. [4] X Trustworthy Source PubMed Central Journal archive from the U.S. National Institutes of Health Go to source

- Your hospital likely has specific consent forms to use. Ask your supervising physician if you're not sure where to get one.

- Some journals also have their own consent form. Check your target journal's author or submission information to make sure. [5] X Research source

How is a case study report structured?

- Even though the introduction is the first part of a case study report, doctors typically write it last. You'll have a better idea of how to introduce your case study to readers after you've written it.

- Your abstract comes at the top, before the introduction, and provides a brief summary of the entire report. Unless your case study is published in an open-access journal, the abstract is the only part of the article many readers will see.

- Many journals offer templates and checklists you can use to make sure your case study includes everything necessary and is formatted properly—take advantage of these! Some journals, such as BMJ Case Reports , require all case studies submitted to use their templates.

Drafting Your Medical Case Study Report

- Patient description

- Chronological case history

- Physical exam results

- Results of any pathological tests, imaging, or other investigations

- Treatment plan

- Expected outcome of treatment

- Actual outcome of treatment

- Why the patient sought medical help (you can even use their own words)

- Important information that helped you settle on your diagnosis

- The results of your clinical examination, including diagnostic tests and their results, along with any helpful images

- A description of the treatment plan

- The outcome, including how and why treatment ended and how long the patient was under your care [11] X Trustworthy Source PubMed Central Journal archive from the U.S. National Institutes of Health Go to source

- You will need references to back up symptoms of the condition, common treatment, and the expected outcome of that common treatment.

- Use your research to paint a picture of the usual case of a patient with a similar condition—it'll help you show how unusual and different your patient's case is.

- Generally, aim for around 20 references—no fewer than 15, but no more than 25. [13] X Trustworthy Source PubMed Central Journal archive from the U.S. National Institutes of Health Go to source

- Close your discussion section with a summary of the lessons learned from the case and why it's significant to consider when treating similar cases in the future.

- Outline any open questions that remain. You might also provide suggestions for future research.

- In your conclusion, you might also give suggestions or recommendations to readers based on what you learned as a result of the case.

- Some journals don't want a separate conclusion section. If that's the case for one of your target journals, just move this paragraph to the end of your discussion section.

Polishing Your Report for Submission to Publishers

- Most titles are fewer than 10 words long and include the name of the disease or condition treated.

- You might also include the treatment used and whether the outcome was successful. When deciding what to include, think about the reason you wrote the case study in the first place and why you think it's important for other clinicians to read.

- Made a significant intellectual contribution to the case study report

- Was involved in the medical care of the patient reported

- Can explain and defend the data presented in the report

- Has approved the final manuscript before submission for publication

- Keep in mind that the abstract is not just going to be the first thing people read—it will often be the only thing people read. Make sure that if someone is going to walk away having only read the abstract, they'll still get the same message they would have if they read the whole thing.

- There are 2 basic types of abstract: narrative and structured. A narrative abstract is a single paragraph written in narrative prose. A structured abstract includes headings that correspond with the sections of the paper, then a brief summary of each section. Use the format preferred by your target journal.

- Look for keywords that are relevant to your field or sub-field and directly related to the content of your article, such as the name of the condition or specific treatments you used.

- Most journals allow 4-8 keywords but check the submission guidelines of your target journal to make sure.

- Blur out the patient's face as well as any tattoos, birthmarks, or unrelated scars that are visible in diagnostic images.

- It's common to thank the patient, but that's up to you. Even if you don't, include a statement indicating that you have the patient's written, informed consent to publish the information.

- Read the journal's submission guidelines for a definition of what that journal considers a conflict of interest. They're generally the same, but some might be stricter than others. [22] X Research source

- If you're not familiar with the citation style used by your target journal, check online for a guide. There might also be one available at your hospital or medical school library.

- Medical librarians can also help with citation style and references if you run into something tricky—don't just wing it! Correct citation style insures that readers can access the materials you cite.

- It's also a good idea to get a beta reader who isn't a medical professional. Their comments can help you figure out where you need to clarify your points.

- Read a lot of case studies published in your target journals—it will help you internalize the tone and style that journal is looking for.

Submitting Your Report to Publishers

- Look into the background and reputation of journals before you decide to submit to them. Only seek publication from reputable journals in which articles go through a peer-review process.

- Find out what publishing fees the journals charge. Keep in mind that open-access journals tend to charge higher publishing fees. [26] X Research source

- Read each journal's submission and editorial guidelines carefully. They'll tell you exactly how to format your case study, how long each section should be, and what citation style to use. [27] X Research source

- For electronic journals that only publish case reports, try BMJ Case Reports , Journal of Medical Case Reports , or Radiology Case Reports .

- If your manuscript isn't suitable for the journal you submitted to, the journal might offer to forward it to an associated journal where it would be a better fit.

- When your manuscript is provisionally accepted, the journal will send it to other doctors for evaluation under the peer-review process.

- Most medical journals don't accept simultaneous submissions, meaning you'll have to submit to your first choice, wait for their decision, then move to the next journal on the list if they don't bite.

- Along with your revised manuscript, include a letter with your response to each of the reviewer's comments. Where you made revisions, add page numbers to indicate where the revisions are that address that reviewer's comments.

- Sometimes, doctors involved in the peer review process will indicate that the journal should reject the manuscript. If that's the case, you'll get a letter explaining why your case study report won't be published and you're free to submit it elsewhere.

- Some journals require you to have your article professionally copy-edited at your own cost while others do this in-house. The editors will let you know what you're responsible for.

- With your acceptance letter, you'll get instructions on how to make payment and how much you owe. Take note of the deadline and make sure you pay it as soon as possible to avoid publication delays.

- Some journals will publish for free, with an "open-access option" that allows you to pay a fee only if you want open access to your article. [32] X Research source

- Through the publishing agreement, you assign your copyright in the article to the journal. This allows the journal to legally publish your work. That assignment can be exclusive or non-exclusive and may only last for a specific term. Read these details carefully!

- If you published an open-access article, you don't assign the copyright to the publisher. The publishing agreement merely gives the journal the right to publish the "Version of Record." [33] X Research source

How do I find a suitable case for a report?

- A rare disease, or unusual presentation of any disease

- An unusual combination of diseases or conditions

- A difficult or inconclusive diagnosis

- Unexpected developments or responses to treatment

- Personal impact

- Observations that shed new light on the patient's disease or condition

- There might be other members of your medical team that want to help with writing. If so, use one of these brainstorming sessions to divvy up writing responsibilities in a way that makes the most sense given your relative skills and experience.

- Senior doctors might also be able to name some journals that would potentially publish your case study. [36] X Research source

Expert Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://www.elsevier.com/connect/authors-update/the-dos-and-donts-of-writing-and-publishing-case-reports

- ↑ https://www.bmj.com/content/350/bmj.h2693

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5686928/

- ↑ https://health.usf.edu/medicine/internalmedicine/im-impact/~/media/B3A3421F4C144FA090AE965C21791A3C.ashx

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2597880/

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6476221/

- ↑ https://www.springer.com/gp/authors-editors/authorandreviewertutorials/writing-a-journal-manuscript/title-abstract-and-keywords/10285522

- ↑ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2597880/

- ↑ https://thelancet.com/pb/assets/raw/Lancet/authors/tl-info-for-authors.pdf

- ↑ https://jmedicalcasereports.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13256-017-1351-y

- ↑ https://guides.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/casereports

- ↑ https://casereports.bmj.com/pages/authors/

- ↑ https://jmedicalcasereports.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1752-1947-7-239

- ↑ https://research.chm.msu.edu/students-residents/writing-a-case-report

- ↑ https://authorservices.taylorandfrancis.com/publishing-your-research/moving-through-production/copyright-for-journal-authors/#

About This Article

Medical Disclaimer

The content of this article is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, examination, diagnosis, or treatment. You should always contact your doctor or other qualified healthcare professional before starting, changing, or stopping any kind of health treatment.

Read More...

To start a medical case study report, first choose a title that clearly reflects the contents of the report. You’ll also need to list any participating authors and develop a list of keywords, as well as an abstract summarizing the report. Your report will need to include an introduction summarizing the context of the report, as well as a detailed presentation of the case. Don’t forget to include a thorough citation list and acknowledgements of anyone else who participated in the study. For more tips from our Medical co-author, including how to get your case study report published, keep reading! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Sep 5, 2020

Did this article help you?

Asfia Banu Pasha

Apr 10, 2017

Jun 20, 2021

Mar 1, 2017

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Develop the tech skills you need for work and life

Case report

Journal of Medical Case Reports welcomes well-described reports of cases that include the following:

- Unreported or unusual side effects or adverse interactions involving medications.

- Unexpected or unusual presentations of a disease.

- New associations or variations in disease processes.

- Presentations, diagnoses and/or management of new and emerging diseases.

- An unexpected association between diseases or symptoms.

- An unexpected event in the course of observing or treating a patient.

- Findings that shed new light on the possible pathogenesis of a disease or an adverse effect.

Case reports submitted to Journal of Medical Case Reports should make a contribution to medical knowledge and must have educational value or highlight the need for a change in clinical practice or diagnostic/prognostic approaches. The journal will not consider case reports describing preventive or therapeutic interventions, as these generally require stronger evidence.

Authors are encouraged to describe how the case report is rare or unusual as well as its educational and/or scientific merits in the covering letter that accompanies the submission of the manuscript.

Any images should protect the patient’s anonymity as far as possible. Any photos or medical imaging should not show the patient's name, medical record number, or date of birth. Images should be cropped only to show the key feature. As per journal policy, JMCR does not consider images with patient faces or patient facial features. If an image of a face must be published, this should be cropped so that only the affected area is shown.

Consent for publication is a mandatory journal requirement for all case reports . Written informed consent for publication must be obtained from the patient (or their parent or legal guardian in the case of children under 18, or from the next of kin if the patient has died). For more information, please see our editorial policies .

Patient ethnicity must be included in the Abstract and in the Main Body under the Case Presentation section.

Reporting standards

For case reports, Journal of Medical Case Reports requires authors to follow the CARE guidelines . The CARE checklist should be provided as an additional files. Submissions received without these elements will be returned to the authors as incomplete.

The checklist will not be used as a tool for judging the suitability of manuscripts for publication in Journal of Medical Case Reports , but is intended as an aid to authors to clearly, completely, and transparently let reviewers and readers know what authors did and found. Using the CARE guideline to write the case report and completing the CARE checklist are likely to optimize the quality of reporting and make the peer review process more efficient.

Preparing your manuscript

The information below details the section headings that you should include in your manuscript and what information should be within each section.

Please note that your manuscript must include a 'Declarations' section including all of the subheadings (please see below for more information).

Title page

The title page should:

- "A versus B in the treatment of C: a randomized controlled trial", "X is a risk factor for Y: a case control study", "What is the impact of factor X on subject Y: A systematic review, A case report etc."

- or, for non-clinical or non-research studies: a description of what the article reports

- if a collaboration group should be listed as an author, please list the Group name as an author. If you would like the names of the individual members of the Group to be searchable through their individual PubMed records, please include this information in the “Acknowledgements” section in accordance with the instructions below

- Large Language Models (LLMs), such as ChatGPT , do not currently satisfy our authorship criteria . Notably an attribution of authorship carries with it accountability for the work, which cannot be effectively applied to LLMs. Use of an LLM should be properly documented in the Methods section (and if a Methods section is not available, in a suitable alternative part) of the manuscript

- indicate the corresponding author

The Abstract should not exceed 350 words. Please minimize the use of abbreviations and do not cite references in the abstract. The abstract must include the following separate sections:

- Background: why the case should be reported and its novelty

- Case presentation: a brief description of the patient’s clinical and demographic details, the diagnosis, any interventions and the outcomes

- Conclusions: a brief summary of the clinical impact or potential implications of the case report

Keywords

Three to ten keywords representing the main content of the article.

The Background section should explain the background to the case report or study, its aims, a summary of the existing literature.

Case presentation

This section should include a description of the patient’s relevant demographic details, medical history, symptoms and signs, treatment or intervention, outcomes and any other significant details.

Discussion and Conclusions

This should discuss the relevant existing literature and should state clearly the main conclusions, including an explanation of their relevance or importance to the field.

List of abbreviations

If abbreviations are used in the text they should be defined in the text at first use, and a list of abbreviations should be provided.

Declarations

All manuscripts must contain the following sections under the heading 'Declarations':

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication, availability of data and materials, competing interests, authors' contributions, acknowledgements.

- Authors' information (optional)

Please see below for details on the information to be included in these sections.

If any of the sections are not relevant to your manuscript, please include the heading and write 'Not applicable' for that section.

Manuscripts reporting studies involving human participants, human data or human tissue must:

- include a statement on ethics approval and consent (even where the need for approval was waived)

- include the name of the ethics committee that approved the study and the committee’s reference number if appropriate

Studies involving animals must include a statement on ethics approval and for experimental studies involving client-owned animals, authors must also include a statement on informed consent from the client or owner.

See our editorial policies for more information.

If your manuscript does not report on or involve the use of any animal or human data or tissue, please state “Not applicable” in this section.

If your manuscript contains any individual person’s data in any form (including any individual details, images or videos), consent for publication must be obtained from that person, or in the case of children, their parent or legal guardian. All presentations of case reports must have consent for publication.

You can use your institutional consent form or our consent form if you prefer. You should not send the form to us on submission, but we may request to see a copy at any stage (including after publication).

See our editorial policies for more information on consent for publication.

If your manuscript does not contain data from any individual person, please state “Not applicable” in this section.

All manuscripts must include an ‘Availability of data and materials’ statement. Data availability statements should include information on where data supporting the results reported in the article can be found including, where applicable, hyperlinks to publicly archived datasets analysed or generated during the study. By data we mean the minimal dataset that would be necessary to interpret, replicate and build upon the findings reported in the article. We recognise it is not always possible to share research data publicly, for instance when individual privacy could be compromised, and in such instances data availability should still be stated in the manuscript along with any conditions for access.

Authors are also encouraged to preserve search strings on searchRxiv https://searchrxiv.org/ , an archive to support researchers to report, store and share their searches consistently and to enable them to review and re-use existing searches. searchRxiv enables researchers to obtain a digital object identifier (DOI) for their search, allowing it to be cited.

Data availability statements can take one of the following forms (or a combination of more than one if required for multiple datasets):

- The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the [NAME] repository, [PERSISTENT WEB LINK TO DATASETS]

- The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

- All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

- The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due [REASON WHY DATA ARE NOT PUBLIC] but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

- Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

- The data that support the findings of this study are available from [third party name] but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of [third party name].

- Not applicable. If your manuscript does not contain any data, please state 'Not applicable' in this section.

More examples of template data availability statements, which include examples of openly available and restricted access datasets, are available here .

BioMed Central strongly encourages the citation of any publicly available data on which the conclusions of the paper rely in the manuscript. Data citations should include a persistent identifier (such as a DOI) and should ideally be included in the reference list. Citations of datasets, when they appear in the reference list, should include the minimum information recommended by DataCite and follow journal style. Dataset identifiers including DOIs should be expressed as full URLs. For example:

Hao Z, AghaKouchak A, Nakhjiri N, Farahmand A. Global integrated drought monitoring and prediction system (GIDMaPS) data sets. figshare. 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.853801

With the corresponding text in the Availability of data and materials statement:

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the [NAME] repository, [PERSISTENT WEB LINK TO DATASETS]. [Reference number]

If you wish to co-submit a data note describing your data to be published in BMC Research Notes , you can do so by visiting our submission portal . Data notes support open data and help authors to comply with funder policies on data sharing. Co-published data notes will be linked to the research article the data support ( example ).

All financial and non-financial competing interests must be declared in this section.

See our editorial policies for a full explanation of competing interests. If you are unsure whether you or any of your co-authors have a competing interest please contact the editorial office.

Please use the authors initials to refer to each authors' competing interests in this section.

If you do not have any competing interests, please state "The authors declare that they have no competing interests" in this section.