- Help & FAQ

Systematic literature review in management and business studies: a case study on university–industry collaboration

- Hunter Centre For Entrepreneurship

Research output : Book/Report › Other report

Publication series

- systematic literature review

- business studies

- business research

Access to Document

- 10.4135/9781526467263

Fingerprint

- Systematic Review Social Sciences 100%

- Case Studies Social Sciences 100%

- Collaboration Social Sciences 100%

- Business Studies Social Sciences 100%

- Management Social Sciences 100%

- Research Psychology 100%

- Case Study Psychology 100%

- Systematic Literature Review Psychology 100%

T1 - Systematic literature review in management and business studies

T2 - a case study on university–industry collaboration

AU - Al-Tabbaa, Omar

AU - Ankrah, Samuel

AU - Zahoor, Nadia

PY - 2019/1/10

Y1 - 2019/1/10

N2 - Although it first appeared in the medical sciences, the systematic literature review has become an established methodology in reviewing the accumulated knowledge in different fields. It is useful for scrutinizing and synthesizing a large volume of research on a specific topic or phenomenon, seeking to generate new insights from integrating empirical evidence, identifying knowledge gaps and inconsistencies, and setting directions for future research. Accordingly, in this case study, we aim to illustrate the steps for developing a rigorous systematic review in business and management research. Specifically, we reflect on our experience in systematically reviewing the research produced on University–Industry Collaboration phenomenon. We show examples of the different steps, stages, and activities involved in this approach, and discuss the various decisions we made throughout our research journey. Moreover, we provide learned lessons, highlight caveats, and offer suggestions and guidance for enhancing the rigor of future systematic literature review research.

AB - Although it first appeared in the medical sciences, the systematic literature review has become an established methodology in reviewing the accumulated knowledge in different fields. It is useful for scrutinizing and synthesizing a large volume of research on a specific topic or phenomenon, seeking to generate new insights from integrating empirical evidence, identifying knowledge gaps and inconsistencies, and setting directions for future research. Accordingly, in this case study, we aim to illustrate the steps for developing a rigorous systematic review in business and management research. Specifically, we reflect on our experience in systematically reviewing the research produced on University–Industry Collaboration phenomenon. We show examples of the different steps, stages, and activities involved in this approach, and discuss the various decisions we made throughout our research journey. Moreover, we provide learned lessons, highlight caveats, and offer suggestions and guidance for enhancing the rigor of future systematic literature review research.

KW - systematic literature review

KW - business studies

KW - business research

U2 - 10.4135/9781526467263

DO - 10.4135/9781526467263

M3 - Other report

T3 - Sage Research Method Cases

BT - Systematic literature review in management and business studies

PB - SAGE Publications Ltd

CY - Thousand Oaks, California

Browse Econ Literature

- Working papers

- Software components

- Book chapters

- JEL classification

More features

- Subscribe to new research

RePEc Biblio

Author registration.

- Economics Virtual Seminar Calendar NEW!

How to Undertake an Impactful Literature Review: Understanding Review Approaches and Guidelines for High-impact Systematic Literature Reviews

- Author & abstract

- Related works & more

Corrections

- Amrita Chakraborty

- Arpan Kumar Kar

Suggested Citation

Download full text from publisher.

Follow serials, authors, keywords & more

Public profiles for Economics researchers

Various research rankings in Economics

RePEc Genealogy

Who was a student of whom, using RePEc

Curated articles & papers on economics topics

Upload your paper to be listed on RePEc and IDEAS

New papers by email

Subscribe to new additions to RePEc

EconAcademics

Blog aggregator for economics research

Cases of plagiarism in Economics

About RePEc

Initiative for open bibliographies in Economics

News about RePEc

Questions about IDEAS and RePEc

RePEc volunteers

Participating archives

Publishers indexing in RePEc

Privacy statement

Found an error or omission?

Opportunities to help RePEc

Get papers listed

Have your research listed on RePEc

Open a RePEc archive

Have your institution's/publisher's output listed on RePEc

Get RePEc data

Use data assembled by RePEc

- Systematic Review

- Open access

- Published: 10 May 2024

A systematic review of thromboembolic complications and outcomes in hospitalised COVID-19 patients

- Hanies Yuhana Othman 1 ,

- Izzati Abdul Halim Zaki 1 , 2 ,

- Mohamad Rodi Isa 3 ,

- Long Chiau Ming 4 &

- Hanis Hanum Zulkifly 1 , 2

BMC Infectious Diseases volume 24 , Article number: 484 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

Thromboembolic (TE) complications [myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and pulmonary embolism (PE)] are common causes of mortality in hospitalised COVID-19 patients. Therefore, this review was undertaken to explore the incidence of TE complications and mortality associated with TE complications in hospitalised COVID-19 patients from different studies. A literature search was performed using ScienceDirect and PubMed databases using the MeSH term search strategy of “COVID-19”, “thromboembolic complication”, “venous thromboembolism”, “arterial thromboembolism”, “deep vein thrombosis”, “pulmonary embolism”, “myocardial infarction”, “stroke”, and “mortality”. There were 33 studies included in this review. Studies have revealed that COVID-19 patients tend to develop venous thromboembolism (PE:1.0-40.0% and DVT:0.4-84%) compared to arterial thromboembolism (stroke:0.5-15.2% and MI:0.8-8.7%). Lastly, the all-cause mortality of COVID-19 patients ranged from 4.8 to 63%, whereas the incidence of mortality associated with TE complications was between 5% and 48%. A wide range of incidences of TE complications and mortality associated with TE complications can be seen among hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Therefore, every patient should be assessed for the risk of thromboembolic complications and provided with an appropriate thromboprophylaxis management plan tailored to their individual needs.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

By the end of 2019, cases of pneumonia of unknown etiology, believed to have been caused by a new coronavirus named Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and later known as COVID-19 disease were discovered [ 1 ]. The lung epithelium, myocardium, and vascular endothelium are the major sites where the SARS-CoV-2 virus binds to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor, which results in lung and cardiovascular complications [ 2 ].

Aside from pulmonary complications, cardiovascular complications such as cardiac injury, heart failure, arrhythmia, and atherosclerosis were also reported during the early phases of COVID-19 outbreak [ 3 , 4 ]. In these cardiovascular complications, endothelial inflammation (endotheliitis) and dysfunction due to the viral infection affected vascular homeostasis and organ perfusion [ 5 ]. Endotheliitis is found to be associated with hyperpermeability, vascular endothelial dysfunction, and thrombus formation, eventually resulting in thromboembolic (TE) complications [ 6 ].

As more clinical cases emerge, episodes of TE complications, such as arterial thrombosis or venous thrombosis, in hospitalized patients have been widely observed [ 7 ]. Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) characterize venous thromboembolism (VTE) [ 8 ], while arterial thromboembolism (ATE) typically manifests as myocardial infarction (MI) or stroke [ 9 ].

A cross-sectional study performed in Wuhan, China [ 10 ] with a study population of 143 COVID-19 patients reported that approximately half of their hospitalised COVID-19 patients ( n = 66) developed deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Approximately 35% ( n = 23/66) of COVID-19-related deaths were observed among those who developed DVT.

A validated mortality prognostic tool identified a few demographic and clinical risk factors, such as age, male sex, hypertension, and obesity, as risk factors for severe disease progression and death in COVID-19 patients [ 11 ]. Advanced age is one of the identified mortality risk factors, and it may be due to a high level of reactive oxygen species that could injure vascular endothelial cells and eventually cause TE complications [ 12 ].

Furthermore, hospitalized COVID-19 patients with pre-existing comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease, active cancer, diabetes, or a history of TE complications are more likely to be at risk of developing TE complications and mortality [ 13 ]. In this review, we aimed to explore the incidence of TE complications in hospitalized COVID-19 patients and the mortality outcomes associated with TE complications from different studies.

Materials and methods

A literature review was performed using the ScienceDirect and PubMed databases for research articles published. The search strategy was completed using keywords and subject headings related to “COVID-19”, “thromboembolic complications”, “venous thromboembolism”, “arterial thromboembolism”, “deep vein thrombosis”, “pulmonary embolism”, “myocardial infarction”, “stroke”, and “mortality”.

The inclusion criteria of the published articles were based on the study design of observational studies comprising both prospective and retrospective studies that reported on the incidences of TE complications in COVID-19. Meanwhile, the outcome of the studies focused on episodes of venous thromboembolism (deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism) or arterial thromboembolism (myocardial infarction and stroke) and mortality in COVID-19 patients who developed TE complications during hospitalization.

The publication dates included articles published from March 2020 to September 2023. In addition, there was no geographical restriction in the systematic review if the articles were published in English language to ensure the transparency and reliability of all relevant studies. We implemented a SIGN checklist approach to assess the risk of bias in the included study (Table 1 ).

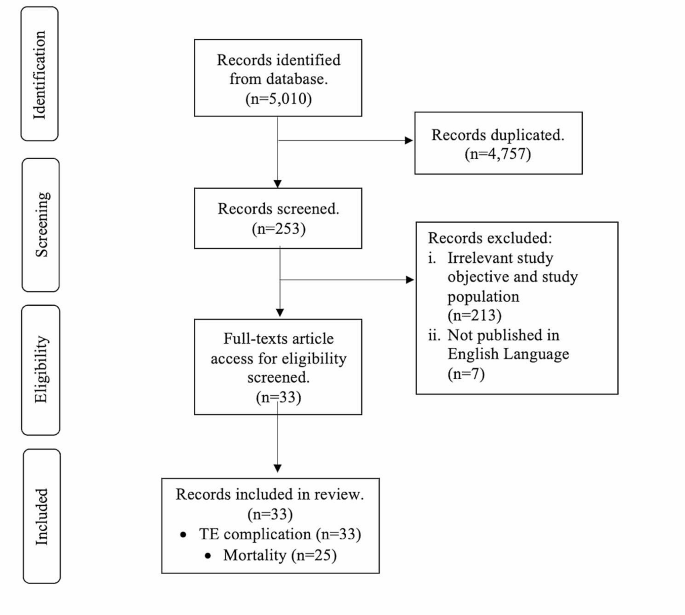

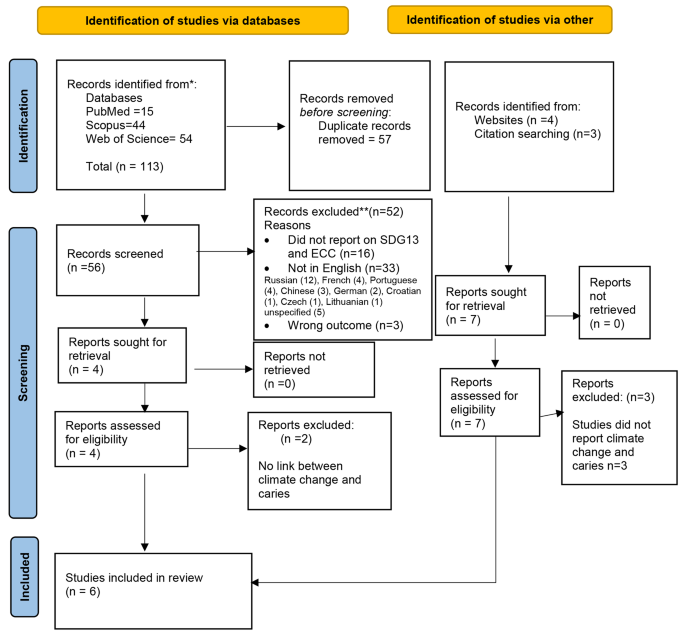

The exclusion criteria were all irrelevant study design, topics, and outcomes that were not related to hospitalized COVID-19 patients who developed TE complications. Any duplicate publications, or articles that were not published or accessed in the English language were excluded from the screening and eligibility process (Fig. 1 ).

PRISMA flowchart on study selection

Based on the keywords used in the database, we found a total of 5,010 research articles. Finally, after the selection of articles based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, there were 33 studies included in this review regarding the incidence of TE complications and mortality outcomes among hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Most of the included studies have been performed in Europe ( n = 18) [ 14 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 22 , 23 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 39 , 43 , 44 , 46 ], the United States of America (USA) ( n = 9) [ 15 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 38 , 40 , 41 , 45 ], Asia ( n = 2) [ 21 , 42 ], North Africa ( n = 2) [ 16 , 24 ] and the United Kingdom [ 28 , 37 ]. The majority of the studies were conducted retrospectively ( n = 27) [ 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 44 , 46 ], whereas only six studies were conducted prospectively [ 14 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 43 , 45 ]. All study participants were hospitalized with COVID-19 patients, ranging from 23 [ 21 ] to 5,966 [ 34 ] patients. These studies included patients who were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) ( n = 8) [ 14 , 18 , 27 , 28 , 32 , 33 ], general wards ( n = 12) [ 16 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 29 , 30 , 35 , 36 , 38 , 40 , 41 , 45 ] or a combination of both the ICU and general wards ( n = 13) [ 15 , 17 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 31 , 34 , 37 , 39 , 42 , 44 ] (Table 2 ).

Incidence of TE complications in hospitalized COVID-19 patients

Fourteen studies reported both the incidence of VTE (PE and/or DVT) and ATE (stroke and/or MI) in their study population [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 22 , 23 , 25 , 32 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 ]. Twenty-seven studies [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 20 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 28 , 29 , 31 , 32 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 ] reported the incidence of PE ranging from 1.0% [ 41 ] to 57% [ 35 ] with the lowest reported in the USA and the highest in Europe. Patients admitted to the general ward had the highest incidence of PE at 57% [ 35 ], followed by those in the ICU and general ward at 40% [ 39 ], and those admitted to the ICU alone at 22.2% [ 18 ] (Table 2 ).

Among the 22 studies [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 25 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 32 , 34 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 ] included, DVT was seen among 0.4% ( n = 21/5966) [ 34 ] to 84.2% ( n = 32/38) [ 27 ] of COVID-19 patients seen in European studies. Critically ill patients in the ICU had the highest incidence of 84.2% ( n = 32/38), followed by 82.6% ( n = 19/23) in the general ward population [ 21 ] and 2.3% ( n = 9/400) in the combination of the ICU and general ward [ 15 ] (Table 1 ). According to two articles that observed both PE and DVT, the current incidence of VTE was approximately 9.0% ( n = 82/915) [ 30 ] in the COVID-19 population and increased five-fold ( n = 81/188) [ 33 ] in severely ill COVID-19 patients (Table 2 ).

Twelve studies specifically reported the incidence of both VTE and ATE in their study population [ 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 23 , 25 , 32 , 41 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 ]. Although one study [ 16 ] showed a higher incidence of ATE [stroke:15.2% and MI:8.7%] than VTE [PE:13.0% and DVT:4.3%], other studies ( n = 11) showed that VTE was more common than ATE, with the incidence of PE [1.0% [ 41 ] to 34.6% [ 45 ] and DVT [0.5% [ 23 ] to 7.7% [ 18 ] compared to stroke [0.5% [ 15 ] to 15.2% [ 16 ] and MI [0.5% [ 23 ] to 8.7% [ 16 ].

Fourteen studies reported the incidence of MI and stroke in a hospitalized COVID-19 population [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 22 , 23 , 25 , 32 , 41 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 ]. The incidence of MI ranged from 0.5% ( n = 6/1127) [ 23 ] to 8.7% ( n = 4/46) [ 16 ] with lower rates observed in European studies (0.5-5.0%) [ 18 , 23 ].

Meanwhile, studies conducted in North Africa, Europe, and the USA revealed that the current incidence of stroke in COVID-19 patients varied between 0.5% ( n = 2/400) [ 15 ] and 15.2% ( n = 7/46) [ 16 ] with Americans having the lowest incidence (0.5–3.8%) [ 15 , 45 ] (Table 2 ). Patients admitted to general COVID-19 wards commonly experienced both events, with the North African population having the highest incidences of both stroke and MI (Table 2 ).

Outcomes in COVID-19 patients associated with TE complications

In this review, three main outcomes for every hospitalized COVID-19 patient were investigated: discharge, being still hospitalized, and death. To standardize the second outcome in all studies, patients who continued to be in the ICU or general ward, transferred to the general ward from the ICU, or transferred to another hospital were classified as “still hospitalized”.

Eleven articles recorded patients’ discharge status in their studies [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 25 , 27 , 29 , 30 , 34 , 35 , 40 ]. The number of discharged patients ranged from 12.0% ( n = 22) [ 14 ] to 79.1% ( n = 22) [ 34 ] (Table 2 ). Patients in the general ward exhibited a higher tendency to discharge (45.7% [ 16 ] to 77.2%) [ 30 ] compared to those in the ICU [ 14 ] to 60.5% [ 27 ] (Table 3 ).

Meanwhile, there were twelve articles [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 22 , 25 , 27 , 29 , 30 , 34 , 35 , 40 ] reported that 1.1% ( n = 68) [ 34 ] to 80.8% ( n = 485) [ 22 ] of their patients remained hospitalized with higher tendencies among those in the ICU compared to patients in the general ward [75.5% [ 14 ] vs. 39.1% [ 16 ] respectively] (Table 3 ).

Lastly, 21 studies [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 22 , 25 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 ] recorded patients’ death status with incidence ranging from 4.8% ( n = 30) [ 42 ] to 63.1% ( n = 125) [ 28 ]. COVID-19 patients who were critically ill had a higher incidence of mortality [12% ( n = 23) to 63% ( n = 125]) than those in the general ward [35.6% ( n = 248]) (Table 3 ).

Incidence of mortality in COVID-19 patients associated with TE complications

Meanwhile, there were 16 studies that reported mortality associated with TE complications [ 16 , 18 , 23 , 25 , 27 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 33 , 35 , 36 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 44 , 46 ]. The incidence of mortality in hospitalised COVID-19 patients due to TE complications ranges from 5.3% [ 25 ] to 48.6% [ 46 ]. The ICU setting reported the highest incidence, ranging from 23.6% [ 18 ] to 48.6% [ 46 ]. The general ward has reported a mortality incidence associated with TE complications as high as 42.5% [ 38 ] (Table 4 ).

In this study, the incidence of TE complications and mortality associated with TE complications in hospitalized COVID-19 patients from European, American, African, and Asian populations were reviewed. The findings showed that hospitalised COVID-19 patients had a high tendency to develop TE complications, which could lead to increased mortality, especially in severely ill patients.

A wide range of TE complications can be seen especially PE (1.0-57%) [ 35 , 41 ] and DVT (0.4-84.2%) [ 27 , 34 ] due to large differences in populations across the studies. Although the number of VTE cases reported was relatively comparable with that in other studies, the limited number of patients tended to overestimate the episodes of VTE complications, as the overall cases were summarized in percentage. Hence, studies with small sample sizes tend to report a high incidence of VTE complications [ 20 , 21 , 27 , 35 , 39 , 45 ]. Furthermore, differences in definitions in each study may account for the discrepancy in the incidence of TE complications. For example, a study conducted in the Netherlands [ 33 ] reported the incidence of general VTE complications instead of categorizing each VTE event, resulting in an elevated rate of VTE (43.1%, n = 81/188).

Moreover, the methods used to diagnose TE complications in each study varied, which could lead to wide variability in the reported incidences. A study [ 15 ] found that attending clinicians could not confirm some presumed cases of VTE without clinical evidence consistent with VTE and strong clinical suspicion. This is due to the inability to perform the necessary tests secondary to the diagnostic limitations imposed by the COVID-19 infection.

Aside from that, the wide variation in the incidence of TE complications among hospitalized COVID-19 patients may be due to the absence of a diagnosis for asymptomatic patients, which limits the amount of data collected globally [ 48 ]. Moreover, the high number of patients admitted during the COVID-19 pandemic era led to a limited screening for TE complications throughout their hospitalization period. Moreover, two European studies [ 49 , 50 ] reported that hospital acquired VTE still occurred within 42 days post-discharge and may indicate that some VTE remains undetected, especially in asymptomatic patients.

Similarly, a Dutch study observed no screening for TE complications during admission, unless the patient had a clinical suspicion [ 17 ]. As a result, some TE complications remain undiagnosed. These observations were supported by autopsy findings, in which nearly half of the patients ( n = 11/26) had TE complications, although it was not suspected prior to post-mortem [ 51 ]. Therefore, we may underestimate the actual number of TE complications among hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

It was observed that COVID-19 patients in general populations were more likely to develop VTE as compared to ATE complications [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 52 ]. This is explained by the characteristics of the vein, with low pressure owing to the vessel structure and low velocity owing to blood movement against gravity [ 53 ]. Most hospitalized COVID-19 patients were either bedridden or isolated in their designated wards. Therefore, restricting their movement and slowing blood flow in veins results in low oxygen tension in the venous wall and a cellular response to initiate inflammation-like TE complications [ 54 , 55 ].

This review included seven studies, where the patient outcomes varied depending on the study settings: ICU or general ward: ICU or general ward [ 14 , 16 , 27 , 29 , 30 , 35 , 40 ]. Patients in the general ward had a higher tendency to be discharged [45.7% [ 16 ] to 77.2% [ 30 ] than those in the ICU [12.0% [ 14 ] to 60.5% [ 27 ]. In addition, the incidence of COVID-19 patients who remained hospitalized was also higher among patients in the ICU [15.8% [ 27 ] to 75.5% [ 14 ] than among those in the general ward [13.9% [ 30 ] to 39.1% [ 16 ]. This finding is consistent with that of a previous study [ 9 ] which showed a higher risk of VTE in the critically ill population due to pre-existing comorbidities and risk factors such as active cancer and a previous history of venous thromboembolism compared to those in the general ward.

ICU patients were more likely to experience all-cause mortality [63.1% [ 28 ] vs. 35.6%] [ 38 ]. Similarly, ICU patients also had the highest incidence of TE complication-related mortality compared to the other two wards: the general ward and the combination ward [48.6% [ 46 ] vs. 42.5% [ 38 ] and 37.5% [ 39 ]]. The difference in mortality rates in these studies may be related to the patients’ disease prognosis. Critically ill patients are more likely to become hypercoagulable because they can’t move, use mechanical ventilation, or have nutritional deficiencies compared to patients in the medical ward. This exposed them to a higher risk of mortality [ 56 ]. Our findings suggest that regardless of the condition of the patients during hospitalization, TE complications in hospitalized COVID-19 patients could lead to poor disease prognosis, thereby increasing patient morbidity and mortality.

By recognizing the incidence of TE complications and mortality in the articles, we gain insight into the burden of TE complications among COVID-19 patients and observe their management across different studies. Most studies [ 14 , 15 , 17 , 18 , 23 , 26 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 41 , 42 , 44 , 46 , 57 ] reported administering thromboprophylaxis to their hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Upon recognition of TE complications, patients received a therapeutic dose of anticoagulant in the absence of prophylactic management [ 16 , 34 , 40 , 58 ]. Due to the unknown extent of COVID-19 infection on TE complications at the time, most practitioners had to outweigh the risk and benefit of introducing thromboprophylaxis strategies, either anticoagulants or antiplatelet agents, to hospitalized COVID-19 patients [ 59 ] (Table 5 ).

The incidence of every reported outcome suggests that the management of TE complications used in all studies may be the cause of potential discrepancies. The management of thromboprophylaxis and therapeutic strategies involving antiplatelet or anticoagulant differed according to the study protocol and local guidelines. A post-mortem examination done in seven COVID-19 patients found platelet-rich thrombi in several organs, such as the pulmonary, hepatic, renal, and cardiac microvasculature [ 60 ]. From this finding, we can postulate that the beneficial effect of antiplatelets such as acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) had the advantage of preventing microthrombi in COVID-19 patients [ 61 ]. Furthermore, several studies found ASA has a pleiotropic effect of disturbing virus replication on the endothelium cell, which may target the development of endotheliitis in COVID-19 patients [ 62 , 63 ]. In situations involving endothelial damage whereby the platelets stick to the injured site, causing thrombosis, antiplatelets such as ASA will be relevant in prophylactic treatment in preventing platelets from clumping together, hence causing TE complications [ 64 ]. However, ASA is also known for its bleeding complication, hence making it a contraindication for patients with an existing risk of bleeding.

On the other hand, anticoagulants such as heparin, low molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), or unfractionated heparin (UFH) have anti-inflammatory properties due to their ability to inhibit the formation of thrombin and reduce inflammatory responses [ 65 ]. Moreover, its antiviral potency explains the prevention of COVID-19 viral entry by acting on the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor and interacting with COVID-19 spike glycoprotein [ 61 ]. Despite its advantages of being pluripotent in nature, patients may develop heparin resistance and may need close monitoring of some parameters such as antithrombin activity, platelet count, factor VII, and fibrinogen level [ 63 ].

Several studies compared the outcomes of COVID-19 infection severity or mortality in patients receiving anticoagulant prophylactic dose versus anticoagulant therapeutic dose in hospitalized COVID-19 patients [ 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 ]. Most of the intervention studies found no significant outcomes in both prophylactic and therapeutic groups. An intervention study performed in Brazil compared the prophylactic regime (enoxaparin or UFH) and therapeutic dose (rivaroxaban: stable patients and enoxaparin or UFH: unstable patients). The result of this study found no significant beneficial effect of prophylactic over therapeutic regimes in terms of mortality or length of hospital stay. Instead, there was a significant increase in bleeding events in the therapeutic cohort (8% vs. 2%, p = 0.0010) [ 69 ]. The result was further supported by another intervention study conducted in critically ill hospitalized COVID-19 patients, which found the therapeutic dose of heparin showed no significant superiority in reducing mortality compared to the prophylactic group (OR 0.84; 95 CI: 0.64–1.11) [ 70 ]. Another multicentre randomized trial involving 28 hospitals in 6 countries among moderately ill COVID-19 patients with elevated d-dimer compared the standard prophylactic heparin dose with the standard therapeutic dose [ 66 ]. This study found that the therapeutic group did not show any significant association with a reduction of the primary composite of death, mechanical ventilation, or ICU admission compared with prophylactic heparin (OR: 0.69, 95% CI: 0.43–1.10, P = 0.12).

In contrast, a multicenter randomized clinical trial done by Spyropoulos, Goldin [ 67 ] found that within non-critically ill hospitalized COVID-19 patients, the therapeutic dose (enoxaparin) was associated with a reduction in TE complications (RR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.21–0.66; P < 0.001) and a reduction in mortality at 28 days of hospitalization (relative risk (RR), 0.68; 95% CI, 0.49–0.96; p = 0.03). However, the result was different in critically ill COVID-19 patients in the ICU as the primary outcome, which showed no significant difference in TE complications in both groups (RR 0.92; 95% CI, 0.62–1.39; p = 0.71). Hence, we can presume that the condition of the patient played an important factor in determining which group had a superior beneficial effect.

In addition, the wide range of mortality (12.5-63.1%) [ 14 , 28 ] in critically ill COVID-19 patients may be due to variations in heparin administration and thromboprophylaxis management. According to a study [ 72 ], the incidence of mortality was high in COVID-19 patients with elevated D-dimer levels who did not receive any thromboprophylaxis treatment. Researchers further supported this results by finding that both therapeutic and prophylactic anticoagulant regimens were associated with a reduction in in-hospital mortality compared to patients without anticoagulants [ 51 ].

In addition to the benefit of prophylaxis management in hospitalized COVID-19 patients, researchers in every study need to consider the risk of bleeding in their study populations. This is crucial, as every patient started on an anticoagulant may encounter the risk of hemorrhage. A study conducted by [ 51 ] found that some patients experienced bleeding events after the initiation of anticoagulant treatment. Patients who started on therapeutic doses experienced a higher rate of bleeding compared to those who did not receive any anticoagulants.

Although the episodes of bleeding complications were comparable in both the prophylaxis and therapeutic-dose groups [ 71 ], there was a difference in intensity depending on the type of anticoagulant used. For example, patients who were given a single preventative agent had higher bleeding rates when taking unfractionated heparin (UFH) than when taking low molecular weight heparin (LMWH). On the other hand, patients who were given therapeutic agents had higher bleeding rates when taking LMWH than when taking direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) [ 51 ].

Finally, the limitations of this study should be considered. Although there was no duplication in the selected articles, there may be unintended bias due to the absence of registration in the PROPERO system.

Conclusions

Overall, there was a wide range of incidences of both VTE complications and ATE complications among hospitalized COVID-19 patients (VTE: 0.4-84% and ATE: 0.5-15.2%). Similarly, a wide variation in the incidence between all-cause mortality in COVID-19 and the incidence of mortality associated with TE complications was seen in hospitalized COVID-19 patients (all-cause mortality:4.8-63.1% and mortality associated with TE complications:5.3-48.6%). These discrepancies may be the result of different definitions, diagnostic methods, and prophylaxis management across all the included studies. Multinational, multicenter data included in this review summarized the common occurrence of TE complications and associated mortality in COVID-19 patients. Therefore, every patient should undergo a thorough risk factor assessment for TE complications and allow individualized optimal thromboprophylaxis management to improve the patient’s outcome.

Data availability

All data have been included in the manuscript.

Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020.

Ferrario CM, Jessup J, Chappell MC, Averill DB, Brosnihan KB, Tallant EA, et al. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II receptor blockers on cardiac angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Circulation. 2005;111(20):2605–10.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Liu Y, Zhang H-G. Vigilance on new-onset atherosclerosis following SARS-CoV-2 infection. Front Med. 2021;7:629413.

Article Google Scholar

Adhikari SP, Meng S, Wu Y-J, Mao Y-P, Ye R-X, Wang Q-Z, et al. Epidemiology, causes, clinical manifestation and diagnosis, prevention and control of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) during the early outbreak period: a scoping review. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9(1):1–12.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Nägele MP, Haubner B, Tanner FC, Ruschitzka F, Flammer AJ. Endothelial dysfunction in COVID-19: current findings and therapeutic implications. Atherosclerosis. 2020;314:58–62.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hattori Y, Hattori K, Machida T, Matsuda N. Vascular endotheliitis associated with infections: its pathogenetic role and therapeutic implication. Biochem Pharmacol. 2022;197:114909.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ribes A, Vardon-Bounes F, Mémier V, Poette M, Au-Duong J, Garcia C, et al. Thromboembolic events and Covid-19. Adv Biol Regul. 2020;77:100735.

Avila J, Long B, Holladay D, Gottlieb M. Thrombotic complications of COVID-19. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;39:213–8.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Thomas W, Varley J, Johnston A, Symington E, Robinson M, Sheares K, et al. Thrombotic complications of patients admitted to intensive care with COVID-19 at a teaching hospital in the United Kingdom. Thromb Res. 2020;191:76–7.

Zhang L, Feng X, Zhang D, Jiang C, Mei H, Wang J, et al. Deep vein thrombosis in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: prevalence, risk factors, and outcome. Circulation. 2020;142(2):114–28.

Gue YX, Tennyson M, Gao J, Ren S, Kanji R, Gorog DA. Development of a novel risk score to predict mortality in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1–8.

Wang Q, Zennadi R. Oxidative stress and thrombosis during aging: the roles of oxidative stress in RBCs in venous thrombosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(12):4259.

Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–62.

Klok F, Kruip M, Van der Meer N, Arbous M, Gommers D, Kant K, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145–7.

Al-Samkari H, Karp Leaf RS, Dzik WH, Carlson JCT, Fogerty AE, Waheed A, et al. COVID-19 and coagulation: bleeding and thrombotic manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Blood. 2020;136(4):489–500.

Mohamud MFY, Mukhtar MS. Epidemiological characteristics, clinical relevance, and risk factors of thromboembolic complications among patients with COVID-19 pneumonia at a teaching hospital: retrospective observational study. Annals Med Surg. 2022;77:103660.

Google Scholar

Kaptein FHJ, Stals MAM, Grootenboers M, Braken SJE, Burggraaf JLI, van Bussel BCT, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications and overall survival in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in the second and first wave. Thromb Res. 2021;199:143–8.

Gonzalez-Fajardo JA, Ansuategui M, Romero C, Comanges A, Gomez-Arbelaez D, Ibarra G, et al. Mortality of COVID-19 patients with vascular thrombotic complications. Med Clin (Engl Ed). 2021;156(3):112–7.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Jimenez-Guiu X, Huici-Sanchez M, Rmera-Villegas A, Izquierdo-Miranda A, Sancho-Cerro A, Vila-Coll R. Deep vein thrombosis in noncritically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia: deep vein thrombosis in nonintensive care unit patients. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2021;9(3):592–6.

García-Ortega A, Oscullo G, Calvillo P, López-Reyes R, Méndez R, Gómez-Olivas JD, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and thrombotic load of pulmonary embolism in patients hospitalized for COVID-19 infection. J Infect. 2021;82(2):261–9.

Chen B, Jiang C, Han B, Guan C, Fang G, Yan S, et al. High prevalence of occult thrombosis in cases of mild/moderate COVID-19. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;104:77–82.

Martinot M, Eyriey M, Gravier S, Bonijoly T, Kayser D, Ion C, et al. Predictors of mortality, ICU hospitalization, and extrapulmonary complications in COVID-19 patients. Infect Dis Now. 2021;51(6):518–25.

Munoz-Rivas N, Abad-Motos A, Mestre-Gomez B, Sierra-Hidalgo F, Cortina-Camarero C, Lorente-Ramos RM, et al. Systemic thrombosis in a large cohort of COVID-19 patients despite thromboprophylaxis: a retrospective study. Thromb Res. 2021;199:132–42.

Kajoak S, Osman H, Elnour H, Elzaki A, Alghamdi AJ, Elhaj M, et al. The prevalence of pulmonary embolism among COVID-19 patients underwent CT pulmonary angiography. J Radiation Res Appl Sci. 2022;15(3):293–8.

Tholin B, Fiskvik H, Tveita A, Tsykonova G, Opperud H, Busterud K et al. Thromboembolic complications during and after hospitalization for COVID-19: incidence, risk factors and thromboprophylaxis. Thromb Update. 2022:100096.

Martínez Chamorro E, Revilla Ostolaza TY, Pérez Núñez M, Borruel Nacenta S, Cruz-Conde Rodríguez-Guerra C, Ibáñez Sanz L. Pulmonary embolisms in patients with COVID-19: a prevalence study in a tertiary hospital. Radiología (English Edition). 2021;63(1):13–21.

Bozzani A, Arici V, Tavazzi G, Franciscone MM, Danesino V, Rota M, et al. Acute arterial and deep venous thromboembolism in COVID-19 patients: risk factors and personalized therapy. Surgery. 2020;168(6):987–92.

Elboushi A, Syed A, Pasenidou K, Elmi L, Keen I, Heining C et al. Arterial and venous thromboembolism in critically ill, COVID 19 positive patients admitted to Intensive Care Unit. Ann Vasc Surg. 2022.

Rali P, O’Corragain O, Oresanya L, Yu D, Sheriff O, Weiss R, et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in coronavirus disease 2019: an experience from a single large academic center. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2021;9(3):585–91. e2.

Erben Y, Franco-Mesa C, Gloviczki P, Stone W, Quinones-Hinojoas A, Meltzer AJ, et al. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism among hospitalized coronavirus disease 2019-positive patients predicted for higher mortality and prolonged intensive care unit and hospital stays in a multisite healthcare system. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2021;9(6):1361–e701.

Filippi L, Sartori M, Facci M, Trentin M, Armani A, Guadagnin ML, et al. Pulmonary embolism in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia: when we have to search for it? Thromb Res. 2021;206:29–32.

Brandao A, de Oliveira CZ, Rojas SO, Ordinola AAM, Queiroz VM, de Farias DLC, et al. Thromboembolic and bleeding events in intensive care unit patients with COVID-19: results from a Brazilian tertiary hospital. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;113:236–42.

Haksteen WE, Hilderink BN, Dujardin RWG, Jansen RR, Hodiamont CJ, Tuinman PR, et al. Venous thromboembolism is not a risk factor for the development of bloodstream infections in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Thromb Res. 2021;206:128–30.

Arribalzaga K, Martinez-Alfonzo I, Diaz-Aizpun C, Gutierrez-Jomarron I, Rodriguez M, Castro Quismondo N, et al. Incidence and clinical profile of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized COVID-19 patients from Madrid region. Thromb Res. 2021;203:93–100.

Valle C, Bonaffini PA, Dal Corso M, Mercanzin E, Franco PN, Sonzogni A, et al. Association between pulmonary embolism and COVID-19 severe pneumonia: experience from two centers in the core of the infection Italian peak. Eur J Radiol. 2021;137:109613.

Silva BV, Jorge C, Placido R, Mendonca C, Urbano ML, Rodrigues T, et al. Pulmonary embolism and COVID-19: a comparative analysis of different diagnostic models performance. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;50:526–31.

Whyte MB, Kelly PA, Gonzalez E, Arya R, Roberts LN. Pulmonary embolism in hospitalised patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;195:95–9.

Vivan MA, Rigatti B, da Cunha SV, Frison GC, Antoniazzi LQ, de Oliveira PHK, et al. Pulmonary embolism in patients with COVID-19 and D-dimer diagnostic value: a retrospective study. Braz J Infect Dis. 2022;26(6):102702.

Bruggemann RAG, Spaetgens B, Gietema HA, Brouns SHA, Stassen PM, Magdelijns FJ, et al. The prevalence of pulmonary embolism in patients with COVID-19 and respiratory decline: a three-setting comparison. Thromb Res. 2020;196:486–90.

Chang H, Rockman CB, Jacobowitz GR, Speranza G, Johnson WS, Horowitz JM, et al. Deep vein thrombosis in hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2021;9(3):597–604.

Chaudhary R, Padrnos L, Wysokinska E, Pruthi R, Misra S, Sridharan M, et al. Macrovascular thrombotic events in a Mayo Clinic enterprise-wide sample of hospitalized COVID-19-Positive compared with COVID-19-Negative patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(7):1718–26.

Fujiwara S, Nakajima M, Kaszynski RH, Fukushima K, Tanaka M, Yajima K, et al. Prevalence of thromboembolic events and status of prophylactic anticoagulant therapy in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Japan. J Infect Chemother. 2021;27(6):869–75.

Helms J, Tacquard C, Severac F, Leonard-Lorant I, Ohana M, Delabranche X, et al. High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(6):1089–98.

Lodigiani C, Iapichino G, Carenzo L, Cecconi M, Ferrazzi P, Sebastian T, et al. Venous and arterial thromboembolic complications in COVID-19 patients admitted to an academic hospital in Milan, Italy. Thromb Res. 2020;191:9–14.

Cueto-Robledo G, Navarro-Vergara D-I, Roldan-Valadez E, Garcia-Cesar M, Graniel-Palafox L-E, Cueto-Romero H-D et al. Pulmonary embolism (PE) prevalence in mexican-mestizo patients with severe SARS-COV-2 (COVID-19) pneumonia at a tertiary-level hospital: a review. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2022:101208.

Fraissé M, Logre E, Pajot O, Mentec H, Plantefève G, Contou D. Thrombotic and hemorrhagic events in critically ill COVID-19 patients: a French monocenter retrospective study. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):1–4.

Choudhary S, Sharma K, Singh PK. Von Willebrand factor: a key glycoprotein involved in thrombo-inflammatory complications of COVID-19. Chemico-Biol Interact. 2021;348:109657.

Tan Y-K, Goh C, Leow AS, Tambyah PA, Ang A, Yap E-S, et al. COVID-19 and ischemic stroke: a systematic review and meta-summary of the literature. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;50(3):587–95.

Roberts LN, Whyte MB, Georgiou L, Giron G, Czuprynska J, Rea C, et al. Postdischarge venous thromboembolism following hospital admission with COVID-19. Blood. 2020;136(11):1347–50.

Engelen MM, Vandenbriele C, Balthazar T, Claeys E, Gunst J, Guler I, et al. editors. Venous thromboembolism in patients discharged after COVID-19 hospitalization. Seminars in thrombosis and hemostasis. Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc.; 2021.

Nadkarni GN, Lala A, Bagiella E, Chang HL, Moreno PR, Pujadas E, et al. Anticoagulation, bleeding, mortality, and pathology in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(16):1815–26.

Garcia-Ortega A, Oscullo G, Calvillo P, Lopez-Reyes R, Mendez R, Gomez-Olivas JD, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and thrombotic load of pulmonary embolism in patients hospitalized for COVID-19 infection. J Infect. 2021;82(2):261–9.

Chaudhry R, Miao JH, Rehman A, Physiology. cardiovascular. StatPearls [Internet]: StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

Schofield Z, Baksamawi HA, Campos J, Alexiadis A, Nash GB, Brill A, et al. The role of valve stiffness in the insurgence of deep vein thrombosis. Commun Mater. 2020;1(1):65.

López JA, Kearon C, Lee AY. Deep venous thrombosis. ASH Educ Program Book. 2004;2004(1):439–56.

Abou-Ismail MY, Diamond A, Kapoor S, Arafah Y, Nayak L. The hypercoagulable state in COVID-19: incidence, pathophysiology, and management. Thromb Res. 2020;194:101–15.

Tholin B, Ghanima W, Einvik G, Aarli B, Brønstad E, Skjønsberg OH, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in hospitalised and non-hospitalised patients after COVID-19 diagnosis. Br J Haematol. 2021;194(3):542–6.

Alizadehsani R, Alizadeh Sani Z, Behjati M, Roshanzamir Z, Hussain S, Abedini N, et al. Risk factors prediction, clinical outcomes, and mortality in COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol. 2021;93(4):2307–20.

Kaptein F, Stals M, Huisman M, Klok F. Prophylaxis and treatment of COVID-19 related venous thromboembolism. Postgrad Med. 2021;133(sup1):27–35.

Rapkiewicz AV, Mai X, Carsons SE, Pittaluga S, Kleiner DE, Berger JS et al. Megakaryocytes and platelet-fibrin thrombi characterize multi-organ thrombosis at autopsy in COVID-19: a case series. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;24.

Santoro F, Núñez-Gil IJ, Vitale E, Viana‐Llamas MC, Romero R, Maroun Eid C, et al. Aspirin therapy on prophylactic anticoagulation for patients hospitalized with COVID‐19: a propensity score‐matched cohort analysis of the HOPE‐COVID‐19 Registry. J Am Heart Association. 2022;11(13):e024530.

Florêncio FKZ, Tenório MO, Macedo Júnior ARA, Lima SG. Aspirin with or without statin in the treatment of endotheliitis, thrombosis, and ischemia in coronavirus disease. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2020;53:e20200472.

Khandelwal G, Ray A, Sethi S, Harikrishnan H, Khandelwal C, Sadasivam B. COVID-19 and thrombotic complications—the role of anticoagulants, antiplatelets and thrombolytics. J Family Med Prim Care. 2021;10(10):3561–7.

Krötz F, Sohn H-Y, Klauss V. Antiplatelet drugs in cardiological practice: established strategies and new developments. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2008;4(3):637–45.

Hippensteel JA, LaRiviere WB, Colbert JF, Langouët-Astrié CJ, Schmidt EP. Heparin as a therapy for COVID-19: current evidence and future possibilities. Am J Physiology-Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2020;319(2):L211–7.

Sholzberg M, Tang GH, Rahhal H, AlHamzah M, Kreuziger LB, Áinle FN et al. Effectiveness of therapeutic heparin versus prophylactic heparin on death, mechanical ventilation, or intensive care unit admission in moderately ill patients with covid-19 admitted to hospital: RAPID randomised clinical trial. BMJ. 2021;375.

Spyropoulos AC, Goldin M, Giannis D, Diab W, Wang J, Khanijo S, et al. Efficacy and safety of therapeutic-dose heparin vs standard prophylactic or intermediate-dose heparins for thromboprophylaxis in high-risk hospitalized patients with COVID-19: the HEP-COVID randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(12):1612–20.

Marcos-Jubilar M, Carmona-Torre F, Vidal R, Ruiz-Artacho P, Filella D, Carbonell C, et al. Therapeutic versus prophylactic bemiparin in hospitalized patients with nonsevere COVID-19 pneumonia (BEMICOP study): an open-label, multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Thromb Haemost. 2022;122(02):295–9.

Lopes RD, Furtado RH, Macedo AVS, Bronhara B, Damiani LP, Barbosa LM, et al. Therapeutic versus prophylactic anticoagulation for patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 and elevated D-dimer concentration (ACTION): an open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2021;397(10291):2253–63.

Godoy LC, Neal MD, Goligher EC, Cushman M, Houston BL, Bradbury CA, et al. Heparin dose intensity and organ support-free days in patients hospitalized for COVID-19. JACC: Adv. 2024;3(3):100780.

REMAP-CAP A-a, Investigators A. Therapeutic anticoagulation with heparin in critically ill patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(9):777–89.

Tang N, Bai H, Chen X, Gong J, Li D, Sun Z. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(5):1094–9.

Download references

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Clinical Pharmacy, Fakulti Farmasi, Universiti Teknologi MARA Cawangan Selangor, Kampus Puncak Alam, Bandar Puncak Alam, Selangor, Malaysia

Hanies Yuhana Othman, Izzati Abdul Halim Zaki & Hanis Hanum Zulkifly

Cardiology Therapeutics Research Group, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Puncak Alam, Selangor, Malaysia

Izzati Abdul Halim Zaki & Hanis Hanum Zulkifly

Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Teknologi MARA Selangor, Sungai Buloh Campus, Sungai Buloh, Selangor, Malaysia

Mohamad Rodi Isa

School of Medical and Life Sciences, Sunway University, Sunway City, Selangor, Malaysia

Long Chiau Ming

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Conceptualization, H.H.Z., I.A.H.Z., M.R.I., H.Y.O.; methodology, H.H.Z., L.C.M., I.A.H.Z., M.R.I., H.Y.O.; software, H.Y.O., H.H.Z., L.C.M.; validation, H.Y.O., H.H.Z., A.H., M.R.I., I.A.H.Z.; resources, I.A.H.Z., H.H.Z., H.Y.O.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Y.O., L.C.M., H.H.Z., I.A.H.Z.; writing—review and editing, H.H.Z., L.C.M., I.A.H.Z., M.R.I., H.Y.O.; visualization, H.Y.O., L.C.M., M.R.I.; supervision, H.H.Z.; project administration, M.R.I., I.A.H.Z., H.H.Z., H.Y.O.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Hanis Hanum Zulkifly .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Othman, H.Y., Zaki, I.A.H., Isa, M.R. et al. A systematic review of thromboembolic complications and outcomes in hospitalised COVID-19 patients. BMC Infect Dis 24 , 484 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-024-09374-1

Download citation

Received : 14 November 2023

Accepted : 03 May 2024

Published : 10 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-024-09374-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Venous thromboembolism

- Arterial thromboembolism

- Myocardial infarction

- Deep vein thrombosis

- Pulmonary embolism

BMC Infectious Diseases

ISSN: 1471-2334

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Advertisement

Music in business and management studies: a systematic literature review and research agenda

- Open access

- Published: 27 March 2023

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Elia Pizzolitto ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4569-1365 1

8486 Accesses

2 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Music is the background of life, representing an international language that connects different cultures. It is also significant with respect to economies, markets, and businesses. The literature in the music field has identified several issues related to the role of digitalization in the revolution of music, the distribution of music products, the management and organization of music events, music marketing strategies, and the position of musicians as entrepreneurs. This paper comprises a systematic literature review of the most recent articles discussing the numerous connections between music, business, and management (2017–2022). Through a rigorous protocol, this research discusses the effects of the digital revolution on the music industry, with particular reference to the persisting oligopoly of major labels and the new business models that integrate music streaming and social networks. The findings show the renaissance and relevance of live music events, the fundamental role of segmentation strategies for managing festivals, and the limited presence of sustainability as a priority during festivals and events management. Furthermore, the literature highlights the relevance of discussions concerning musicians’ identity, especially in light of the complex relationship between the bohemian and the entrepreneurial nature of their profession. This is followed by numerous reflections on future research opportunities, recommending theoretical and empirical in-depth studies of music industry competition, futuristic management philosophies and business models, and the roles of technology, sustainability, and financial elements in fostering artists’ success in the digital era. Finally, the paper discusses business models and strategies for musicians, festivals management, stores, and sustainability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Economics, Marketing and Performances of US Classical Music: Journeyin’ Together to de Promise Land

Market Readiness for the Digital Music Industries: A Case Study of Independent Artists

The Impact of the Music Industry in Europe and the Business Models Involved in Its Value Chain

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

As Mithen ( 2009 ; p 3) states, “To be human is to be musical”. Music is part of most individuals’ daily lives. For example, it plays in the background when people make purchases at stores and eat at restaurants. It is a universal language that helps strangers communicate immediately, that spreads and evokes emotions, and that inspires players, producers, and listeners (Cooke 1990 ; Hunter and Schellenberg 2010 ). However, beyond being an artform that can connect people from different cultures (Huron 2001 ) and with different identities (Mithen 2009 ), music is also a business.

The worldwide relevance of music can be recognized not only in philosophical discussions but also in statistical data about the industry. Music consumption has grown quickly, particularly since the start of the digital revolution, and this growth seems unlikely to slow down in the future (IFPI 2022 ). The worldwide music industry has grown significantly in recent years. In fact, it grew from US$14.2 billion in 2014 to US$25.9 billion in 2021, revealing growth of 18.5% in 2021 (IFPI 2022 ). Streaming now drives the music market, representing 65% of global music market revenues in 2021 (IFPI 2022 ). This trend is a consequence of the digital revolution, which has been characterized by two phases of development (Koh et al. 2019 ). The first phase involved physical and digital music record sales. The second phase was the development of streaming, unbundling, and cross-platform services that combined music with other entertainment forms, such as video games, television programs, films, and talent shows (Shen et al. 2019 ).

Two of the most relevant dimensions of the music industry are as follows: (a) the production and distribution of music through physical and digital support networks, as guided by record companies; and (b) the production and distribution of live music, which is controlled by world-famous artists but is characterized by many minor professional musicians, sound technicians, and other workers. These two dimensions are interconnected. The digital revolution is disruptive, and it has upset traditional capitalist economies, but the world of live music has resisted such changes (Azzellini et al. 2021 ). In addition to these two major dimensions, the music industry includes a complex and elaborate set of other dimensions. These comprise the conditions of minor musicians and labels; publishing, managing, and marketing; teaching and other educational activities (Thomson 2013 ); and the conditions of local music and record stores.

In this regard, multiple issues have emerged from the literature, mostly related to the big change that the digital revolution has brought about in the music industry. For example, minor artists and labels have to consider new marketing strategies, and they need to find innovative ways to exploit the easier connections between consumers and their products that technologies allow, despite having limited financial assets (Zhang 2018 ). Another example involves music events or festivals, which face complex challenges because of the recent Covid-19 pandemic. Innovation in the organization and marketing of these events is focused on the concept of value creation, guided by the idea of festivals as chaotic and unpredictable events in which collaboration and co-creation are critical for the achievement of financial, economic, and social objectives (Werner et al. 2019 ). Covid-19 and the digital revolution complicated the conditions of local music and record stores, which are more centered on experience than competition and need stable innovation in their marketing strategies (Trabucchi et al. 2017 ).

Moreover, the growth of the music business has highlighted the complex relationship between musicians’ artistic and entrepreneurial sides. In fact, musicians face cultural barriers to their identification as professionals. As Frederickson and Rooney ( 1990 ) noted, an absence of formal requisites to enter the musical profession is one of its most relevant barriers; because of this lack of a need for credentials, many people do not consider music to be a profession. Indeed, as Henry ( 2013 ) found, few music students think about teaching music as a future profession. According to Pizzolitto ( 2021 ), musicians are reluctant to consider themselves entrepreneurs because of the complex relationship between art and profit. Therefore, the entrepreneurial identity of musicians should be fostered to overcome this obstacle to recognizing music as a profession.

This may be challenging, as the Covid-19 pandemic has adversely affected musicians’ activities. Although the music industry has continued to grow and has not been experienced many negative consequences, there have been numerous (orderly) protests by musicians and sound technicians who feel they have been forgotten by governmental policies. For example, in October 2020, a large group of musicians played in front of the British Parliament to protest a decision to decrease state benefits for freelance workers (Savage 2020 ). During the same month, musicians and sound technicians peacefully occupied many public squares in Italy to broadcast the slogan Esistiamo anche noi , which translates to “We also exist” (Sky Tg24 2020 ). In November 2020, musicians in Berlin held silent protests against a lockdown (Global Times 2020 ). Indeed, music around the world has experienced a number of conflicts.

Beyond the disparities in the success of record companies versus professional musicians, there are philosophical complexities connected to an antinomy between the artistic nature of music and the capitalistic context in which it is developed (e.g., see Bridson et al. 2017 ; Haynes and Marshall 2017 ). Musicians and record producers also face strategic issues concerning the distribution of their music. Waldfogel ( 2017 ) defined the current era as a golden age for music listening, yet musicians and producers experience dilemmas every time they intend to launch a product. One dilemma relates to the many opportunities available because of the digital revolution; for example, one can take advantage of digital platforms, streaming, and physical support networks. However, the increase in options demands more in-depth strategic planning. Thus, the philosophical significance of music to individuals, its relevance to people’s lives, and its importance to the economy are at odds with the research conditions of the field.

While attempts to map the literature on music research have been numerous and of high quality, they have mainly concentrated on the effects of music in the workplace (e.g., Landay and Harms 2019 ) or music education research. For instance, in 2004, volume 32 (issue 3) of Psychology of Music focused on mapping music education research in single national contexts (e.g., Welch et al. 2004 ; Gruhn 2004 ). Moreover, in 2006, Roulston published a methodological paper that incentivized qualitative research in the music field. Therefore, while existing research has discussed content relevant to the field, there is no literature review on the recent development of music in business and management studies, including topics such as digitalization, the conditions of the industry and competition, the management of music events, innovations, sustainability, and the complex position of musicians after the digital revolution. Consequently, this article addresses the research question “How does recent literature debate music in business and management studies?”.

The next section provides details on the methodology used in this literature review. In particular, it gives a detailed explanation of the procedure used to gather data and analyze the content of articles. Following this is a descriptive analysis of the literature sample, including the journals, author affiliations, and methods of the articles, and an analysis of the contents of the articles. The next section studies the themes that emerged in the articles. Finally, future research opportunities, managerial implications, and a general discussion of the results are presented in the conclusion.

2 Methodology

A systematic literature review (SLR) was chosen as the methodology for this study for two main reasons. First, the research questions concern a specific field (i.e., music in business studies). Second, an SLR can ensure a greater degree of objectivity compared with other kinds of literature reviews (e.g., narrative). It can also ensure reproducibility and limit biases in article selection and interpretation (Denyer and Tranfield 2009 ; Post et al. 2020 ). This study used a method described by Wolfswinkel et al. ( 2013 ), where contents of articles are analyzed using a grounded theory approach. This method ensured that the analysis would not be based on any prejudices. Moreover, grounded theory provides the advantage of developing a theoretical framework in the absence of a specific background (Corbin and Strauss 1990 ; Strauss and Corbin 1997 ). Finally, the method published by Wolfswinkel et al. ( 2013 ) exhibited no article selection differences compared with other SLR methodologies (e.g., see Denyer and Tranfield 2009 ; Post et al. 2020 ). Therefore, the method met all the requirements for conducting an SLR as objectively as possible.

2.1 The employed protocol

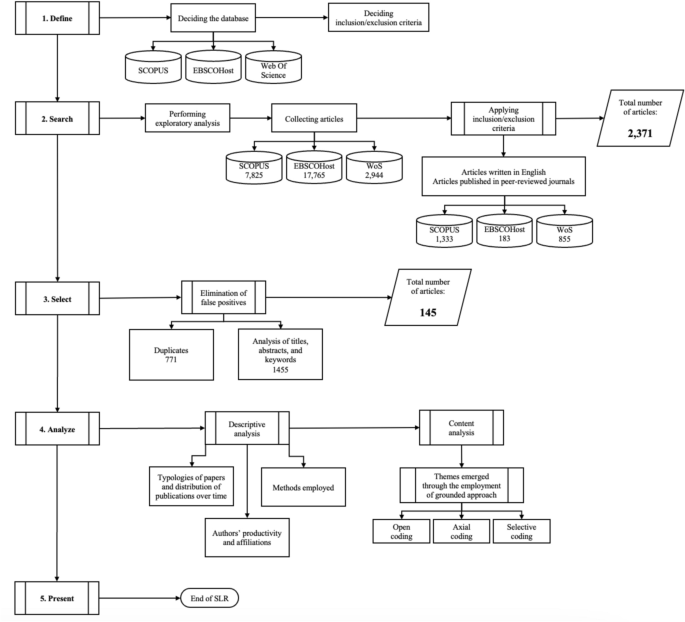

The method included the five following phases: define, search, select, analyze, and present (Fig. 1 ). During the first phase, the database and the inclusion/exclusion criteria for the study were determined. Similar to most SLRs (e.g., see Vrontis and Christofi 2019 ), only articles that were written in English and that had been published in peer-reviewed journals were included in the sample. To ensure that articles of the highest quality would be included, only those listed in the SCOPUS, EBSCOHost, and Web of Science databases were considered. Finally, specific keywords were used to search the three databases and were applied to titles, abstracts, and keywords of the articles. The keywords were music AND ( business OR management ).

Phases of SLR employed protocol

The second phase consisted of the search for articles. This began with several exploratory analyses to ensure that all relevant literature would be included. The research commenced with searching SCOPUS, and 7825 results were retrieved. The results were limited to peer-reviewed articles written in English, which narrowed the list to 3764 results. As the focus was on recent literature regarding music in business studies, the publication years were then restricted to 2017–2022, leaving 1333 results.

The same steps were followed in searching EBSCOHost. The initial dataset included 17,765 results, and after the limitations were applied, 183 articles remained. The steps were repeated in searching Web of Science, resulting in an initial sample of 2944 results. This number decreased to 855 after the limitations were applied.

During the third phase, the 2371 results were refined, and 771 duplicates were eliminated. After screening the titles, abstracts, keywords, and contents, 1444 false positives were eliminated. The final dataset comprised 145 articles.

The last two steps of the procedure were “analyze” and “present.” The next section presents the descriptive and content analyses of the articles (i.e., the results of these steps). Analyzing the articles included determining the type of paper, the distribution of publications over time, the authors’ productivity and affiliations, and the methods employed in the empirical articles. The contents of the articles were analyzed using a grounded theory approach, during which four themes emerged.

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This section details the methods applied when including or excluding articles. To facilitate the selection of articles, an Excel file with 19 columns and 145 rows was created. More than 2700 cells were filled in with the following information for each paper: ID number, DOI, authors, title, publication year, source title, number of citations, source (i.e., SCOPUS, EBSCOHost, or Web of Science), paper type (i.e., empirical, conceptual, review), methodology (i.e., qualitative or quantitative), methods employed, sample size, type of statistical units; authors’ provenience; and theories cited. For reasons of space, the table cannot be shown here, but it is available upon request.

In addition, a column was devoted to the reason for including or excluding a paper. The objective was to consider only articles that explicitly referred to the interconnections between music and business or management issues. The process started with evaluating the titles, abstracts, and keywords to gain an understanding of the articles’ contents. If this evaluation was insufficient, the articles were read for a better evaluation.

To ensure transparency in the selection process, as suggested by Denyer and Tranfield ( 2009 ), some examples are considered. One article that was retrieved from the Scopus database was the article Neumatic singing in Thai popular singing, 1925–1967 by Inkhong et al. ( 2020 ) because it included the keywords used for the initial extraction. The article discussed solutions to problems related to incorrect pronunciation using neumatic singing. Therefore, it was excluded. Another article, Quality management of music education in modern kindergarten: Educational expectations of families by Boyakova ( 2018 ) talked about understanding and improving the quality of children’s music education and made no reference to business or management studies. Therefore, it too was excluded.

Examples of articles that were included are as follows. The article Digital music and the “death of the long tail” by Coelho and Mendes ( 2019 ) discussed the impact of digital distribution in the music market, concentrating on the dualism between the long tail theory and the superstar effect theory. Schediwy et al. ( 2018 )’s article Do bohemian and entrepreneurial career identities compete or cohere? discussed the identity of musicians. The article The role of stakeholders in shifting environmental practices of music festivals in British Columbia, Canada by Hazel and Mason ( 2020 ) discussed festival management. These three articles were relevant to our study and were therefore included in our review.

2.3 Grounded analysis of the articles’ contents

The grounded theory approach employed in this review followed a certain protocol. The 145 papers included in the sample were divided into subsamples of five randomly selected papers using Excel. Open coding was used to label the subsamples with codes to identify concepts and enable comparisons of the articles, including information such as the affiliated intuitions, the methodologies used, and the theoretical in-depth analyses. The final aim is to conceptualize the most relevant aspects and identify categories and subcategories of common elements.

Axial coding was then employed to make connections between the codes and facilitate further comparison of data emerging from the articles and theoretical and methodological frameworks in the various subsamples. The final aim was to build a systematically integrated network of concepts.

Finally, selective coding was employed to conceptualize and improve the results of the previous analyses. The aim was to achieve a well-integrated theoretical reasoning that can be used to simplify and enrich the reflections on the studied phenomenon.

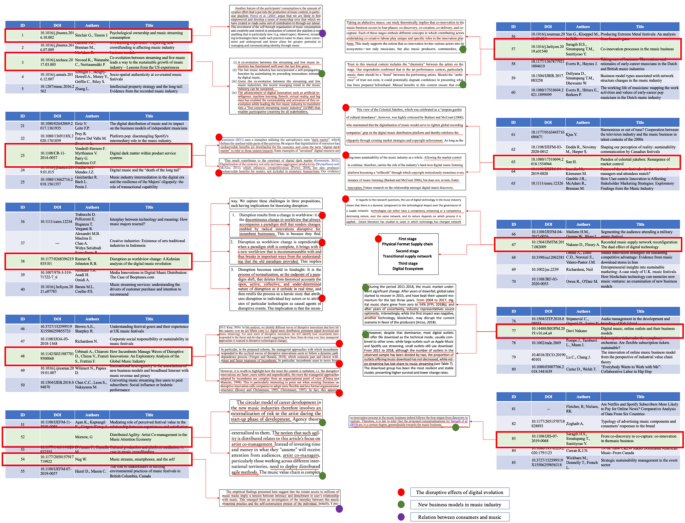

Figure 2 shows an example of how subthemes emerged during the analysis. The blue tables correspond to random samples of five articles. The red oblongs represent the most relevant articles. The black squares represent (a very limited number of) critical codes (open coding). The violet, red, and green circles represent the results of conceptual connections among the codes (axial coding); the interpretation of these connections is shown at the bottom of the figure.

An example of grounded methodology applied in this research (colour figure online)

2.4 Limitations

This literature review tries to develop a complete picture of the most relevant research in music management and business. The aim is to establish a starting point for future in-depth analysis and gathering of future research in this area. Nevertheless, it is not exempt from limitations. First, the methodology, database searches, and analyses were performed by one author. Although the selected method (grounded theory method; see Wolfswinkel et al. 2013 ) was chosen for its ability to reduce objectivity, even in the content analysis of the selected articles, there might be limitations in the application of inclusion and exclusion criteria considering the high number of articles.

Second, this review employed specific databases to ensure the quality of papers extracted. However, this method inevitably excluded books, book chapters, grey literature, and other sources of information that could be relevant to the topic and in terms of triangulating information and enriching the results of the analysis. Therefore, future research should include the object of the analysis and more sources of information.

Finally, this review limits the time span to recent years. Although SLRs should include a limited number of articles to concentrate on a very specific and relevant research question, the considerable body of knowledge in terms of music management and business suggests that a more comprehensive viewpoint can be considered. Nevertheless, in case future research would be interested in enlarging the time span of the analysis, the amount of articles that would emerge would be studied using quantitative methods, such as meta-analysis or bibliometric analysis.

3 Descriptive analysis

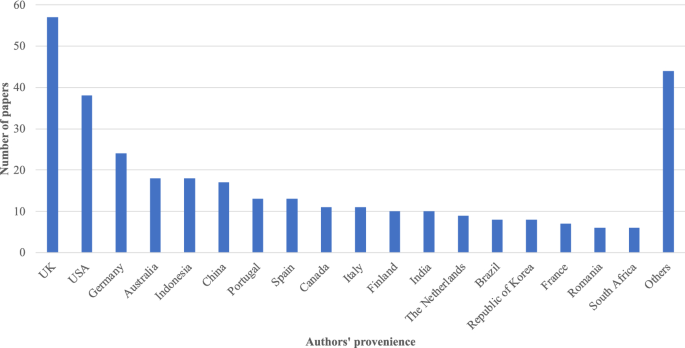

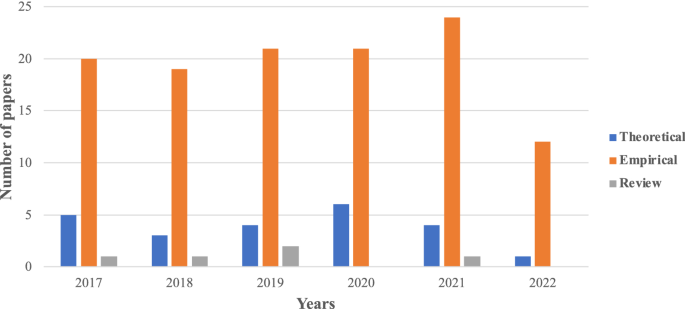

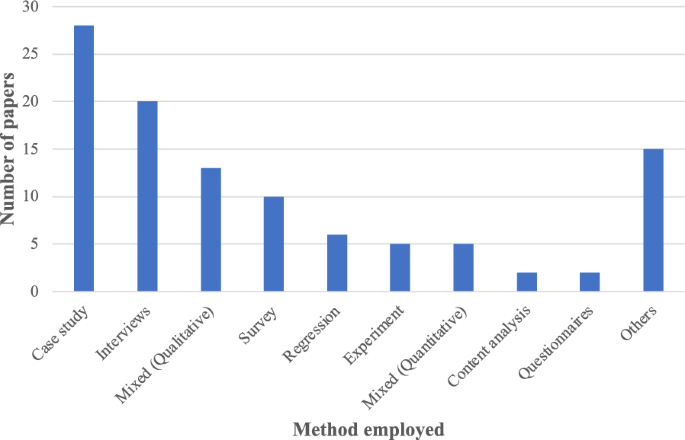

This section presents the descriptive analysis of the selected literature. The analysis focuses on three aspects: (1) the authors’ provenience (Fig. 3 ), (2) the types of papers, and (3) the methods employed in the empirical studies.

Authors’ provenience

The UK and the USA led in terms of the number of relevant articles published in the period under study with 28.96% of the articles. There is a worldwide interest among scientists in terms of music research in business studies. Even though empirical articles are the most common in the selected dataset, theoretical articles and literature reviews are present in each of the five years considered. Excluding the year 2022, in which theoretical articles represent less than 8% of the contributions, one fifth of the dataset from 2017 to 2021 consists of theoretical articles and literature reviews. Therefore, there is considerable interest in debating conceptual issues in this field. Qualitative research—particularly case studies (26.42% of the dataset)—is the most common methodology used for performing research in the field. Interviews were also commonly used in the extracted contributions (18.87%). Therefore, it is possible that qualitative frameworks of analysis are the best way to gather and evaluate data in this market (Figs. 4 and 5 ).

Papers’ typology per year

Methods employed in the selected articles

4 Content analysis

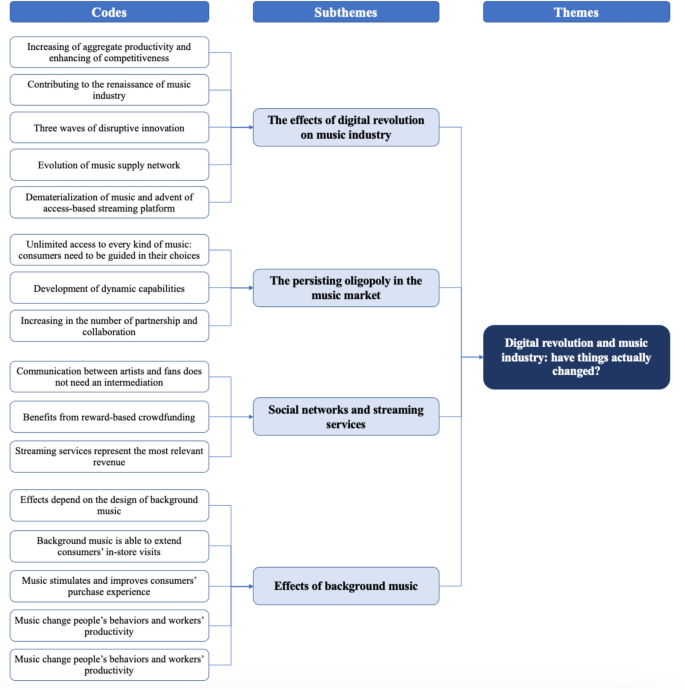

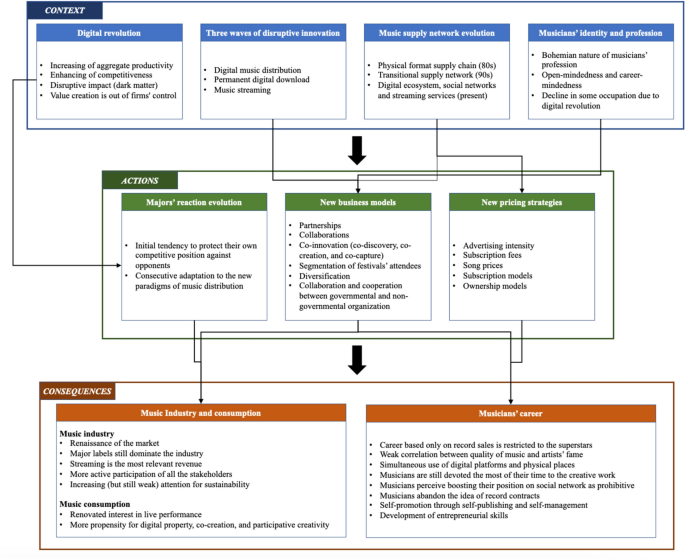

This section presents the results obtained from the grounded analysis of the selected papers. Given the amount of data and the complexity of the concepts, two graphic representations have been created. Figure 6 shows a summary of codes, sub-themes, and themes that emerged from the analysis. Figure 7 shows a conceptual map of the field.

Codes, themes and subthemes emerged from selected literature

Conceptual map

4.1 The digital revolution and the music industry: Have things actually changed?

4.1.1 the effects of the digital revolution on the music industry.

The digital revolution profoundly and directly impacted the economy through direct effects such as an increase in aggregate productivity and competitiveness and through more unobserved effects relating to the development of open-access platforms, new business models, and the need of managers to always achieve a better understanding of consumers’ expectations. These unobserved effects of the digital revolution have been described as digital dark matter (Vendrell-Herrero et al. 2017 ). Moreover, the inevitability of technology-related industry disruption seems not to be totally caught by professionals and firms, which are not reacting appropriately to this phenomenon (Riemer and Johnston 2019 ). For this reason, new business models are theorized in the literature. For example, Morrow ( 2018 ) introduced the concept of distributed agility as a model consisting of a reactive approach through which multiple self-organized teams combine their abilities to respond quickly to the rapid changes in the new digital market.

During the period 2011–2018, digital music and streaming contributed dramatically to the renaissance of the market (Nakano 2019 ). According to Nag ( 2017 ), the dramatic increase in the amount of accessible music contents and the decreasing barriers to consumer access is producing a contradictory effect on the philosophy of consumption. On one side is the benefit of freedom of choice and on the other side is an indirect call for more scarcity.

The literature has recognized three waves of disruptive innovations—digital music distribution, permanent digital downloads, and music streaming (Urbinati et al. 2019 ). Reactions to these things were similar; after an initial majors’ tendency to protect their own competitive position against opponents, there was adaptation to the new paradigms of music distribution. In particular, after the digital music distribution revolution, incumbents concentrated on building online shops and selling music from their catalogues. After the digital download revolution, incumbents verified the weaknesses in their previous strategic reactions and started to build relationships and partnerships with newcomers to fight the increased competition of important innovations such as Apple’s iTunes Music Store. Finally, with the music streaming revolution, entities such as the iTunes Music Store started to consider acquisitions as strategic choices to limit the damage caused by the rapid development of services like Spotify (Urbinati et al. 2019 ).

The music supply network evolved in a similar way. Nakano and Fleury ( 2017 ) identified three stages in this evolution. The first stage in the 1980s was a physical supply chain in which the hierarchical model with a vertical integration structure fostered the power of major labels that controlled technical and market access. The second stage in the 1990s was a transitional supply network in which the captive governance model fostered an open hierarchy. In this phase, the power was in the form of control over market access. Finally, in the last 20 years, the supply network evolved to a digital ecosystem in which individual producers and small and large providers can (at least theoretically) compete with major labels, which are exploiting their accumulated power to control mass market access through collaboration, partnerships, and new business models based on digital outlets and aggregators.

Sinclair and Tinson ( 2017 ) highlighted the problem of the decreasing value of psychological ownership of music guided by the dematerialization of music and the advent of access-based streaming platforms. Nevertheless, the antecedents of psychological ownership—investment of the self, profound knowledge and control of the target, and pride—demonstrated that consumers are modifying their experimentation with psychological ownership, achieving loyalty, empowerment, citizenship, and social rewards as consequences of this phenomenon. Therefore, through the new conceptualization of the psychological ownership of music, consumers are able to control the target of ownership and to develop and protect their music identity.

The other side of the coin of the digital revolution in music is that collaboration between major labels and other actors has allowed them to keep their power and to maintain the oligopoly in the market. In this context, while technological and digital innovation is stimulated, innovation in music is discouraged (Sun 2019 ).

The music industry has reacted to this tendency and has been able to assimilate the technological and digital innovations (Naveed et al. 2017 ). In particular, there are types of innovations that have assumed an increasing level of importance after the digital revolution. For example, co-innovation, a construct comprising co-discovery, co-creation, and co-capture, is widely recognized as a fundamental element in promoting correct governance, leadership, and resource integration (Saragih et al. 2019a , b ).

4.1.2 The persisting oligopoly in the music market