Improve your writing in one of the largest and most successful writing groups online

Join our writing group!

Critique vs. Criticism: How to Write a Good Critique, with Examples

by Daniel Rodrigues-Martin

Understanding critique vs. criticism

We all assign merit to the information we experience daily. We “judge” what we hear on the news. We “evaluate” a university lecture. We “like” or “dislike” a movie, a meal, a photo, a story. We’re all critics.

Some writer-readers struggle with this point, especially if they are young to writing and editing. Sitting in a judgment of another writer’s work often feels distasteful, and doing so may conjure negative memories of when we were misunderstood or dismissed by others.

Conversely, we might be willing to share our opinions with other writers while struggling with our competence. We can’t seem to say anything constructive. If we’re critiquing on Scribophile, we may feel that we are wasting one of the author’s coveted “spotlight” critiques.

Having used Scribophile on-and-off since 2009, I’ve seen countless readers qualify their commentary on my own work (“I don’t read your genre,” “I haven’t read your previous chapters,” “I’m not good with grammar,” etc.) and I’ve seen even more cry woe on the forums about how they can’t critique because they’re not experienced enough, not educated enough, or not talented enough. Others decry the very sort of criticism writers’ groups and workshop sites like Scribophile foster, suggesting that the perfunctory nature of such criticism is ultimately more harmful than helpful.

Scribophile as a community thrives on the principle of serious commitment to serious writing, and the foundation of that commitment is reading and responding to others’ work. If you want to explore some elements helpful to improving your critiquing skills, I invite you to get yourself some hot caffeine, strap on your thinking cap, and read on.

How to write a great critique in 3 steps

Listed here are some ideas I’ve found helpful for approaching others’ work; these tips are about your mindset as a critic. These ideas are by no means exhaustive. The best teacher is experience, and I encourage all writers to reflect on the ways in which they approach others’ work as well as how they can best contribute to the growth of others on and off of Scribophile.

1. If you’re genuine, you’ll be constructive

Being constructive means coming to the critique with the ultimate goal of helping the writer improve. It means always criticizing with good intentions for the writer. It does not equate to coddling—being so nice you’ll never say a hard thing—nor does it equate to browbeating—being so hard you’ll never say a nice thing.

Being dishonest or refusing to offer valid criticism where you’re able is a disservice to the writer. Don’t shy away from honesty. Few things are more constructive than hard truths delivered by critics who genuinely want to help and who tailor their criticism with an attitude of genuine interest.

As you interact with works on Scribophile or elsewhere, remember to always approach the task of criticism with a desire to be genuinely helpful. If your criticism is built on this foundation, your commentary will be constructive regardless of your competence and experience.

2. No jerks

As for literary criticism in general: I have long felt that any reviewer who expresses rage and loathing for a novel or a play or a poem is preposterous. He or she is like a person who has put on full armor and attacked a hot fudge sundae or a banana split. —Kurt Vonnegut

Few things will more quickly deflate a writer than unnecessarily harsh criticism. Being honest and being brutal are not the same thing. Critics must learn to express hard truths without coddling and without being jerks.

Even rude people can be good writers with valuable insights into the craft. The problem is that if you express valid insights obnoxiously, the author won’t care. In order for people to listen, they must feel that the person criticizing them has their best interest in mind, and being harsh doesn’t communicate your best interest.

In my earliest days writing, I received some negative criticism from a writer who decided to berate me for penning a bad phrase rather than explaining to me why the phrase didn’t work. Because he was rude, I insulated myself to his criticism. Years later, I reviewed the work and realized his criticism was valid. The problem was not the content of his criticism, but its malicious delivery. Had he come to my work with the desire to be genuinely helpful, I would have listened to what he had to say, and I might even have gained some enlightenment during a formative time in my writing career. The critic did me doubly wrong not only by being obnoxious, but by retarding my growth as a writer.

Unnecessarily harsh criticism is a sign of literary and personal immaturity. Don’t be a jerk.

3. Don’t be too timid

Flattering friends corrupt. —St. Augustine

Every writer likes to be praised, especially by those not obligated to praise them due to marital status or having given birth to them. But depthless praise can be just as damaging as heartless criticism. The reason for this is that it offers no real commentary on the work.

Refusing to offer criticism where it’s needed is one of the greatest disservices you as a critic can do for other writers. Some critics may fret that their criticism might be too discouraging if fully disclosed. Critics must contend with the reality that writing is art, people have opinions about art, and those opinions are not always going to be eruptions of praise. There is no safer environment to honestly and succinctly point out problem areas in a piece of writing than a forum designed for that very purpose.

None of this is to say that you shouldn’t commend a piece of work if it truly is fantastic or that you should not highlight the gems within a work. Again: constructive criticism is honest criticism. If a work is so well-crafted in your eyes that nothing worse than grammatical hiccups are present, tell the writer. They deserve to know they’ve done a fine job. Sometimes people genuinely deserve a “well done.” Don’t skimp on encouragement where it can be authentically offered. Even if a piece is messy, do your best to find a few strong points to highlight. It will express your best interest—especially if you had a lot of hard things to say.

The difference between a critique vs. criticism is whether it’s constructive

Be constructive , meaning, have the best intentions for helping the writer. This may mean telling hard truths. If hard truths must be told, do so respectfully. If praise is deserved, offer it. Highlight the strong points of a piece—even if they are far outweighed by the negative points. Be genuine in your motivations, and genuine action will follow.

Considering authorial intent while critique writing

This section concerns authorial intent and has as its purpose the critic’s growth as an interpreter of that intent. This section is not so much about judging an author’s intent as it’s about being aware of that intent and factoring that awareness into your commentary.

1. Context is king

It is important to appreciate the amount of subjectivity and pre-understanding all readers and listeners bring to the process of interpreting acts of human communication. But unless a speaker or author can retain the right to correct someone’s interpretation by saying ‘but that’s not what I meant’ or ‘that’s not even consistent with what I meant,’ all human communication will quickly break down. —Craig L. Blomberg

While interpreters are always within their rights to read whatever they want however they want to, what they are not at liberty to decide is authorial intent —what the author desired the audience to receive from their work.

As a reader and a critic, you must be careful to understand an author’s work on their own terms while also interpreting those words. There is a substantial difference between, “This is how I’m hearing what you’re saying,” and, “This is what I say your words mean.” Don’t presume to tell an author what their work is supposed to mean, but do tell them how you’re interpreting what they’ve written.

A work-in-progress can suffer from a variety of ailments. Contextual questions are not cut-and-dry like questions of syntax, grammar, or, to a degree, plotting. Questions of context have to do with the interaction of author intent and reader interpretation. They’re murky waters to navigate because you as the reader have to exercise a bit of telepathy; you have to try and get inside the author’s head, ultimately “What is the author trying to convey with this sentence, this piece? Who is this piece for, and will it successfully communicate with that target audience? Is it clear that there is a target audience?”

Some authors are great at genre pieces; they know all the chords to strike, they know what the tone of the piece should be, the kinds of characters who should appear. Other authors can completely muck it up. They’ll write a romance piece that reads like a technical manual or a flowery memoir with a tangle of dead-ending tangents. It’s not always easy and natural for new critics to explain why something does or doesn’t work, but innately, we know. When those moments come up, let the author know.

2. The unintended/unspoken

Asking the question, “Is that really what you meant?” isn’t always bad. All of us have been misunderstood. Sometimes the results are humorous, but other times, we’re grateful for the opportunity to correct misunderstandings.

If in your criticism you find yourself questioning the use of a word or phrase, or even of a character, idea, or plot point, it’s advisable to bring such questions to the writer’s attention. It may just be you, but it may not just be you. Unless the writer has a philosophical axe to grind, they probably mean to communicate clearly, and it should at least be made known that they may have botched it up.

Conversely, there are instances where things left unwritten speak volumes. Perhaps a character “falls off the radar” in mid-scene, and it leaves you scratching your head? It may be appropriate to point out confusing instances of the unwritten for the author’s consideration.

Because my own novel employs many neologisms, critics jumping in mid-story often highlight those neologisms to make sure I’m using them as intended. While it can get tedious to say to myself, “Yes, that is what it means,” I am always thankful for keen eyes. This is the kind of sharp, considerate criticism each of us should aim for and be thankful for if we receive it.

3. Accounting for genre and intended audience

A genre is “A category of artistic composition, as in music or literature, marked by a distinctive style, form, or content.” When reading an author’s work, it’s crucial to take into account its genre and intended audience. If you’re even-handed in your critiquing, you’ll at some point be reading a story in a genre you might not otherwise touch, and while you might wish Twilight had been a one-off rather than a worldwide phenomenon, it’s inappropriate to harshly judge an author’s work simply because you don’t like their sort of story.

Consider the question of author intent and how that intent will resonate with an intended (or unintended!) audience. Sometimes, you must ignore whether or not a story resonates with you personally. Instead, ask yourself if it would resonate with your vampire-novel-loving daughter. Are the story, plot devices, characters, and verbiage appropriate for the intended audience? If yes, why or why not? If no, why or why not? Your personal tastes should not dictate the quality of your criticism. Train yourself to offer valuable insight even on writing you’d never pay money to read.

Remember these principles when reading work outside your sphere of interest. Being constructive doesn’t mean you have to love or even like the work. If something is written well, it’s written well—prejudices aside. If you’re truly unable to be objective, you would do the writer a better service by moving on.

4. Don’t pretend to be a non-writer

A film director watches other films differently than a moviegoer. A chef tastes a meal differently than the average person. As a writer, you necessarily see stories differently than non-writers. That’s not a bad thing.

We can be helpful to other writers by sharing our gut reactions no differently than an unversed beta reader. On the other hand, writers should be able to explain with more clarity than the average person why something does or doesn’t work in a story. A writer’s insight is of a different quality than a non-initiate’s insight. Both are needed for success, because if a writer one day moves on to pitch their work to those in the literary establishment, that work will not be judged by average readers until after it has survived the professional gauntlet.

All readers have the ability to share their gut reactions, but not all readers can slip on their “writer glasses” and offer critique on that level. Good critiques provide both types of insight, so as a fellow writer, bring your full experience to bear in helping others embarking on the same journey.

Understanding intent is part of a good critique

As best as you’re able, judge an author’s work on the basis of their intent—this includes noting instances of the unintended! In consideration of genre, judge the work not on the basis of your interest in the genre, but on the author’s skill at writing a piece that strikes the proper chords within the genre they’ve chosen. It’s not possible for you to read as a reader only, so don’t pretend to be something you’re not.

What makes a good critique?

A good writer may come out of any intellectual discipline at all. Every art and science gives the writer its own special ways of seeing, gives him experience with interesting people, and can provide him with means of making a living… It is not necessary—or perhaps even advisable—that the young writer major in literature. —John Gardner

Contrary to the belief of a lot of new writers, learning to write and critique doesn’t require sixty-four credits of college English or an MFA. Plenty of writers and editors don’t hold English or Creative Writing degrees, and while I in no way wish to discourage those who choose to improve their writing and reviewing by taking the high road of formal education, neither do I wish to discourage the 98% of you reading this who haven’t and won’t be able to front the money and time for such an education.

The ability to forge valid criticism is an applied skill learned through a combination of technical knowledge and experience. We’re fortunate to live in an age where vast quantities of technical information are available at our fingertips. Contemporary writers are able to write informed literature like never before. So, too, are critics able to fact-check writers like never before.

Just as you’re willing to fact-check history or science before you include something in your story, it doesn’t hurt to do that for those you critique. Granted, they should do that themselves, but maybe they’re writing a genre you write, or maybe they’re writing about your field of work or interest? Being educated or experienced in any field will enrich not only your writing, but your critiquing. If you’re a fry cook, your ability to write or critique a scene in a modern commercial kitchen is better than that of someone who hasn’t had that experience. Because you know what it’s like to really work in a kitchen, you can speak to the authenticity of any such scene, and you can speak to the authenticity of the kinds of people who work in commercial kitchens. Your grammar may not be the best, but you still have something valuable to contribute.

Great writers are keen observers of life, and their writing both informs and is by informed by life. Bring the authenticity of your life to your writing and your criticism. You have perspectives, knowledge, and experiences others don’t. As you read and respond to authors, employ the skills and knowledge you already possess. Put your formal and informal education and your life experience to work. This is what it means to “write what you know” and, in our case, “critique what you know.”

Immerse yourself in all sorts of stories to get better at critiquing

One of the cardinal “writing for dummies” rules is that if you want to write well, you need to read a lot. I don’t doubt the validity of this statement, but books are only one medium of storytelling among many. My contention is that by immersing yourself in movies, television, and other storytelling mediums, you can learn about dialogue, plot, characterization, and all the other aspects of “storytelling” that appear no matter what medium you choose.

If you want to understand what makes a story great, seek out great stories. Immerse yourself in them. Though you may not be able to verbalize it, your innate understanding of what makes a narrative work will grow. This will improve both your writing and your critiquing.

Steal critiquing techniques from smart people–yourself included

Consider the critiques that have been most helpful to you. Why did they work? Reread them if you must. Then find a way to adapt the good things from those critiques into your own criticism.

Consider the critiques you’ve shared that have been helpful to others. What stood out to the author? You may even consider asking an author for feedback on your critique. Ask how you could have been more helpful.

Critiquing is a skill you can improve over time just like writing itself. But like writing, it takes practice and discipline. Make it easier on yourself by nurturing what works.

A reading list to improving your critique writing skills

There are many solid books on writing that will not only improve your writing, but your critical reading skills. Rather than provide you a hundred sources, here are a few I’ve been able to get my claws on, have dug into, and can personally vouch for:

Good Prose , by Tracy Kidder & Richard Todd. The writer-editor combo of The Atlantic share their wisdom through a tightly-edited, insightful, and entertaining survey of nonfiction writing that has plenty of benefit for writers of all stripes. The book’s section on “proportion and order” in narrative has revolutionized my own thinking about how stories should be structured.

How to Write Science Fiction and Fantasy , by Orson Scott Card. A good resource if you write these genres, Card provides practical advice on publishing, agents, etc., in addition to familiarizing the reader with dos and don’ts for writing Sci-Fi/Fantasy, including some technical questions. The book’s a bit dated by now—especially the parts about the publishing world—but there are some nuggets of timeless truth within.

On Becoming a Novelist , by John Gardner. Despite the Modernistic tendency of abusing the pronoun “he,” this may be the most formative thing I’ve read about novel writing. It’s slim, readable, practical, and comprehensive.

On Writing , by Stephen King. Something of an autobiography penned by one of the most successful authors of all time, this book is snappy, humorous, entertaining, and more than a little instructive for anyone looking to write and read better. King reminds his fellow writers that “Life isn’t a support system for art; it’s the other way around.”

Story , by Robert McKee. Considered by many to be the “screenwriter’s bible,” Story belongs in the library of every serious writer whether or not they ever aspire to the silver screen. McKee is a master of properly balancing a plot to satisfy an audience, and all writers should glean from his wisdom.

The Modern Library Writer’s Workshop , by Stephen Koch. Koch flexes his student’s muscles by providing copious citations from the masters who have graced the past few centuries of literature. The author fades into the background at points while readers are treated to the musings and experiences of Dostoevsky, Flannery O’Connor, Hemingway, and others.

The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers , by Christopher Vogler. Vogler is one of the most proficient living writers of the entertainment industry. Working primarily from the theses of the late cultural anthropologist, Joseph Campbell, Vogler illustrates the plot devices and character tropes that underlie the world’s oldest stories. Recommended for new writers of the speculative fiction genres and those who wish to write epics.

The value of criticism and critiquing

The arts too can be taught, up to a point; but except for certain matters of technique, one does not learn the arts, one simply catches on. —John Gardner

The value of criticism is twofold: First and most obviously, it helps others. Second, and maybe not as apparent if you’re new to critiquing: It improves your own writing.

As you examine the work of others, you’ll be able to see what works and what doesn’t work. You will begin to notice patterns as you edit your own writing, and you’ll begin to sift out the problem areas. It’s difficult to judge your own work objectively. Doing it for others helps you get a clear head and recognize the ways in which you do the very things you criticize others for doing.

This article hasn’t had as a goal the outlining of a criticism “process.” The reason for this is that I could no more outline a criticism process than I could outline a fiction writing process. There is no single monolithic “right way to do it” that will unequivocally work for everyone. Herein are general guidelines and considerations that I’ve found helpful over the years and that others have appreciated. If you write critiques constructively, taking consideration of what the author is trying to do, and if you do so authentically, drawing on your experiences and knowledge, you’re on the right track for writing great critiques. The details of how exactly you accomplish that will become clearer to you as you engage in criticism. As in any discipline: Seek feedback and keep going.

Appendix I: “Line edits” and “critiques”

“Line edits” and “critiques” are not the same thing. These two types of reader responses address different issues, and in order to ensure that you receive the kind of criticism you’re seeking, you need to know what you’re displaying.

A “line edit” is a thorough, line-by-line examination of a manuscript. A good line edit requires an editor with a keen eye for detail and a working knowledge of contemporary grammar, syntax, and idiomatic English. The purpose of a line edit is to make a manuscript as readable as possible by removing technical errors. Typically, works that receive line edits receive them because they’re in need of them.

A “critique” is an in-depth review, touching on characterization, plot, theme, scene structure, poetry of language, and other related factors. Notice how I didn’t list anything about spelling or proper comma usage? It’s because that’s not critiquing; that’s editing. Typically, works that receive criticism as described here are free or mostly free of errors that distract readers from the story.

No one is perfect, and one of the best tools at our disposal on Scribophile is the inline critique option. Having never read nor submitted a flawless piece of writing for review, I can tell you that no one should be ashamed to receive a line edit. There are many sharp eyes and sharp minds browsing Scribophile, and even the best writer’s eyes glaze over after so many hours of staring at a white screen.

That said, part of what is absolutely necessary to receive genuine criticism as described above is a readable text. An unreadable text has never, in my experience, provided foundation for a fantastic piece of writing. Messy prose screams “messy story.” If you want criticism of story, your text must be as clean as possible.

If you’re willing to admit that your mastery of the technicalities of writing is not the sharpest, by all means, employ the knowledge and expertise of those on this site who do; it’s a wonderful resource. Readers can’t truly resonate with your story until you weave a piece of art that makes them forget they’re experiencing a piece of art. When you’re able to achieve this, you’ve removed the hurdles preventing your reader from authentically engaging with the story you’ve created. It’s at this stage in your writing that you can consistently receive deep criticism.

This is, of course, not to say that imperfect prose can’t be critiqued. Part of writing great critiques is learning to spot the gems in the story and encouraging the writer to press onward in spite of any shortcomings. If you’re honest and genuine, this won’t be a problem.

If all else fails, list at the top of your submitted piece the sort of critique you’re seeking by highlighting specific questions. “I’d love to know how you reacted when X happened,” for example. This will encourage readers to engage with the sorts of questions you’re asking.

Appendix II: The Benefits and Limits of Critique Groups

If you understand how to best leverage critique groups, they will be helpful and formative to your growth. As written above, critiquing others helps you grow; but there is more. The benefits of critique groups are threefold.

First, broad exposure. Want to know what people outside of your social circle will think of your work? A critique group will expose your work to people of different backgrounds. You can learn how a teen writer with big dreams or a Native American ex-botanist writing a memoir in retirement reacts to your story. This is the type of demographic insight you’d pay good money for when it comes time to sell your book. Even in small chunks, it’s valuable to know how different people experience your work.

Second, many eyes forge sharper prose. If three different people all trip over the same thing in your text, the problem is most likely not those three people, but your text. Especially if your text is hot off the press, you can catch errors early, and writers tend to be sharper with these sorts of things than the general population. Go look up the cost of a professional manuscript editor in your area, and you’ll be glad for many eyes combing over your writing.

Third, and most importantly: networking. The goal of sites like Scribophile and in-person critique groups should be to develop a network of people who will read the entirety of your work. Don’t get angry at forks for not being spoons—a reader jumping in mid-story will never give you the same level of commentary as someone who’s been reading since chapter one. If you’re ready for that level of reading, you need others to agree to read the book from start to finish. Use critique groups and sites like Scribophile to build relationships. Be attentive to others and share good critiques with them. As your relationships deepen, you’ll eventually find yourself with a list of contacts to trade with. But this requires you to be the kind of person people want reading their work. Behave professionally, and over time, you’ll find yourself surrounded by likeminded individuals who will give you the kind of meaty, informed commentary you need. The rule of thumb with critique groups and workshop websites is: You get out what you put in to them.

Appendix III: Still confused?

If you have questions I have failed to address in this article, I encourage you to contact me privately here on Scribophile or to reach out on social media. I’m happy to help.

Get feedback on your writing today!

Scribophile is a community of hundreds of thousands of writers from all over the world. Meet beta readers, get feedback on your writing, and become a better writer!

Join now for free

Related articles

Screenplay Format: How to Format a Script, with Examples

What Is a Beta Reader? (And Why You Need One!)

Understanding First Serial Rights & Other Author Rights

The Copyright Guide for Writers (with a “Poor Man’s Copyright” Example)

Short Story Submissions: How to Publish a Short Story or Poem

How to Become a Beta Reader

Skip to content. | Skip to navigation

Masterlinks

- About Hunter

- One Stop for Students

- Make a Gift

- Access the Student Guide

- Apply to Become a Peer Tutor

- Access the Faculty Guide

- Request a Classroom Visit

- Refer a Student to the Center

- Request a Classroom Workshop

- The Writing Process

- The Documented Essay/Research Paper

- Writing for English Courses

- Writing Across the Curriculum

- Grammar and Mechanics

- Business and Professional Writing

- CUNY TESTING

- | Workshops

- Research Information and Resources

- Evaluating Information Sources

- Writing Tools and References

- Reading Room

- Literary Resources

- ESL Resources for Students

- ESL Resources for Faculty

- Teaching and Learning

- | Contact Us

To critique a piece of writing is to do the following:

- describe: give the reader a sense of the writer’s overall purpose and intent

- analyze: examine how the structure and language of the text convey its meaning

- interpret: state the significance or importance of each part of the text

- assess: make a judgment of the work’s worth or value

FORMATTING A CRITIQUE

Here are two structures for critiques, one for nonfiction and one for fiction/literature.

The Critique Format for Nonfiction

Introduction

- name of author and work

- general overview of subject and summary of author's argument

- focusing (or thesis) sentence indicating how you will divide the whole work for discussion or the particular elements you will discuss

- objective description of a major point in the work

- detailed analysis of how the work conveys an idea or concept

- interpretation of the concept

- repetition of description, analysis, interpretation if more than one major concept is covered

- overall interpretation

- relationship of particular interpretations to subject as a whole

- critical assessment of the value, worth, or meaning of the work, both negative and positive

The Critique Format for Fiction/Literature

- brief summary/description of work as a whole

- focusing sentence indicating what element you plan to examine

- general indication of overall significance of work

- literal description of the first major element or portion of the work

- detailed analysis

- interpretation

- literal description of second major element

- interpretation (including, if necessary, the relationship to the first major point)

- overall interpretation of the elements studied

- consideration of those elements within the context of the work as a whole

- critical assessment of the value, worth, meaning, or significance of the work, both positive and negative

You may not be asked in every critique to assess a work, only to analyze and interpret it. If you are asked for a personal response, remember that your assessment should not be the expression of an unsupported personal opinion. Your interpretations and your conclusions must be based on evidence from the text and follow from the ideas you have dealt with in the paper.

Remember also that a critique may express a positive as well as a negative assessment. Don't confuse critique with criticize in the popular sense of the word, meaning “to point out faults.”

Document Actions

- Public Safety

- Website Feedback

- Privacy Policy

- CUNY Tobacco Policy

A Guide to Critiquing a Story: Seven Vital Elements Every Story Must Have

Frequently authors ask if I have a “form” that I used to help me critique a story. Given the large number of things that I look at in a story, any form that I had would simply be too long to be workable. Yet it makes sense to try to codify the critiquing process.

There are of course people who don’t believe that art can or should be measured. They might say, “Sure, this author uses the passive voice so much that his tale flows slower than cold tar, but his stunning insights are unsurpassed in literature.” They’d be right. Yet if you’ve ever had to judge stories professionally, you soon find that you have to devise some logic for deciding how to gauge the relative merits of tales, and I’ve been judging stories for contests and classes for some twenty years.

So I’m going to create a form that I might use to judge a story:

Story Critique Form

1. Originality. On a scale of 1 to 10, how original was this story? A 1 means that the story is cliché while a 10 means that it has at least a couple of ideas that I haven’t encountered before. ______

2. Setting. On a scale of 1 to 10, how well was the setting developed? A 1 indicates that the setting was poorly developed. This means that is almost completely disappeared from the story, or that I felt confused as to where and when the tale took place in one or more scenes. Of course, the author should involve all of the senses in describing his or her setting. A 10 means that not only is the setting well-developed, but it informs every aspect of the story—from character development to tone and narrative style. In a story that rates a 10, the setting itself is a powerful draw for the story, and the author succeeded in transporting me into the tale. ______

3. Characterization. On a scale of 1 to 10, how well-drawn are the characters in the story? Good characters should convince us that they grew up in the world or setting that we’ve placed them in. They should have complex motives and be imbued with conflicting attitudes about life, ethics, politics, and so on. The characters should have friends, enemies, acquaintances, secrets, desires and fears. The character should have a physical body, with a physical history. The character should have a family, of course, and some type of history, along with a place in society. In short, with a poorly drawn character, we know virtually nothing about him by the end of the story. With a well-drawn character, we feel as if we know him intimately by the end of the story. ______

4. Conflict and Plot. On a scale of1 to 10, how interesting are the conflicts? Since the characters, along with their motives and abilities really lead to a plot, then one must also consider the twists and turns of the plot. How inventive are they? How exciting? How engrossing? ______

5. Emotional/intellectual payoff. On a scale of 1 to 10, how well did this story arouse powerful emotions? If it did arouse powerful emotions, were they the proper emotions for the intended audience (as gauged by the age and sex of the protagonists)? Remember that the author shouldn’t be hitting the same emotional beats over and over again. Instead, the author should be creating an emotional symphony, where counter-beats help raise the emotional payoff. ______

6. Theme. On a scale of 1 to 10, how well did this story speak to the reader? Does it raise interesting questions about life and provide profound insights? A rating of “1” means that I don’t really see either one. A rating of “10” means that the author astounded me. ______

7. Treatment. On a scale of 1 to 10, how masterfully was the tale written on a line-by-line basis? A poor story, a tale that earns a 1, might be difficult to read simply because of something like “pronoun reference problems,” or it may be marred by typos and grammatical problems. A tale worthy of a 10 will be written not only in language that is beautiful and evocative, but it will also move with effortless pacing. Too often, authors who write beautifully work too hard to impress the reader and end up cluttering the tale will too many metaphors or overwrought pacing. In doing so, they struggle to draw attention to themselves rather than tell a story. ______

These are the big-ticket items that I look for in a story. You’d think that there would be more, but as you can see I lump things into large categories. For example, an author’s “treatment” can include hundreds of items. An author might have a surprisingly large and facile vocabulary, and that would be a plus. Yet the same author might labor to create clumsy or artless similes and thus mar his work. General pacing and story flow might be part of the author’s style, or I might rank it under plotting, but it is taken into consideration.

There is one other consideration. How do you weight different categories? Is one element more important than the others?

Personally, I want a story that scores perfect tens in all categories, but I know authors who feel that in fantasy and science fiction, for example, a story with an original concept is solid gold. So a story that is fresh and original will beat out one that is beautifully written.

Similarly, in a genre such as romance, where you might well be writing with very strict guidelines, you might not be free to create radically unusual characters or unusual settings.

In short, the audience is looking for a product that delivers a powerful emotional charge. So in that genre, the story might be weighted toward emotional power.

In an upcoming post, I’m going to take the story form and break it down further, discussing some of the things that I look for when I’m considering each category.

Guest Blogger, David Farland , Coordinating Judge of the Writers of the Future Contest.

David Farland is an award-winning, international bestselling author with over 50 novels in print. He has won the Philip K. Dick Memorial Special Award for “Best Novel in the English Language” for his science fiction novel On My Way to Paradise , the Whitney Award for “Best Novel of the Year” for his historical novel In the Company of Angels , and many more awards for his work. He is best known for his New York Times bestselling fantasy series The Runelords .

The judging criteria you detail in your 9/2017 article are useful to me. Now, how about your take on how writers can do this on their own, i.e., when and how and what. How do you know when you nailed it. Some of the points I can see come before ever taking up the pen, like originality. That is the main area in which I fall down, I believe.

Lawrence, There are several articles on the blog site about writing from several of our Contest judges. Have a look to see if any of them answer your need. If not, let me know and I will request from one of our judges an article on how they deal with this issue.

I found this article very useful to me as well, but I have one problem. As I am not a professional judge I cannot properly evaluate which stories get a “10” in something. The place to look, obviously, is the yearly anthology, where the best stories are found. However, as David Farland pointed out, not all the stories selected score a ten in all categories, if any did. So I read a story in the anthology (Useless Magic vol. 33, for example) and to me the dialogue seems stilted, the conclusion is drawn out and unsatisfying. The problem is thus: I can’t be sure if my assumptions are correct and I should avoid these pitfalls, or am I simply not mature enough to understand it. I would suggest the following (although I don’t know if it is reasonable) is that a few stories could be analyzed by the judges so that aspiring writers could know that: story A has a fascinating mileu and a strong theme, but it’s prose is weak, or, story B has a beautiful prose but it’s scientific veracity is questionable, etc.

Hello Reuben and thank you for your comment. I would recommend you join the WOTF Forum where you will find past winners and judges willing to help you out by reviewing your story and making suggestions. Here is the link: http://forum.writersofthefuture.com/

Is john goodwin the author of this article?? Can you help me in evaluating text content, elements, features and properties using a set of criteria? What criteria would fall under content, elements, features and properties?

Hi Ana, We have created the Writers of the Future Forum which you can join and find others who help each other long with such matters. The link to join (it’s free) is http://forum.writersofthefuture.com/

I wish you well.

Best, John Goodwin

Describing the cultural and social setting of your fantasy world provides you with a great opportunity to use your imagination. These cultural and social settings basically contain the specific details and elements that make your world distinct and running. When writing your fantasy story, make sure to pay attention to such details as the common cultural practices, the political system, the history, and more. Aside from this, you should also make consistent rules for your fictional world. For example, if the characters in your fictional world are all wizards with magic, then establish such fact or rule all throughout your story. Do not make sudden changes, as doing so may tend to confuse your readers. You can find my blog here: https://www.daughtersoftwilight.com/a-general-guide-on-writing-fantasy-fiction/ hope it helps to your writing journey.

Thank you for your contribution and referenced blog.

This is one of the useful articles that I am looking for so long, and thanks to that Google brought me here. You ought to compose on the grounds that you love the state of stories and sentences and the production of various words on a page. Composing comes from perusing, and perusing is the best instructor of how to compose.

Extraordinary post! I will bookmark your blog and offer this to my companions. This is one of the extraordinary records with respect to sentimental anticipation books. Keep it up!

Thank you, Monique. I am glad you enjoy it. If you look at the website itself, https://www.writersofthefuture.com , you will also see that we have a Forum, podcast, free online writing workshop taught by Orson Scott Card, Tim Powers, and David Farland.

All the words written above are very helpful. I could compose recorded fiction, or sci-fi, or a secret however since I think that it’s intriguing to investigate the pieces of information of some little know period and build up a story dependent on that, I will likely keep on doing it. Please come and visit my blog on Tips and Tricks for Writing Historical Fiction Hope this will help you as well.

Cheers Keith

Loved your content John, very well-written! I have been reading posts regarding this topic and this post is one of the most interesting and informative ones I have read. Thank you for this!

You are very welcome!

Great stories shock us. They cause us to think and to feel. They stick in our psyches and assist us with recalling thoughts and ideas such that a PowerPoint packed with visual diagrams won’t ever can. You can check out and visit my blog on https://byronconnerbooks.com/the-secrets-to-telling-a-powerful-story/

Great information. Fantasy is an important fixing in living, it’s a perspective on through some unacceptable finish of a telescope. Thanks for posting.

Fiction refers to literary works that are created from the imagination, rather than being based strictly on real events or facts. In fiction, authors invent characters, settings, and plotlines to tell a story.

Leave a Reply

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Writers & Illustrators Contests

- Writer Contest

- Writer Contest Rules

- Illustrator Contest

- Illustrator Contest Rules

Related Sites

- L. Ron Hubbard

- Author Services, Inc.

- Galaxy Press

- Battlefield Earth

Connect With Us

- Educator Resources

Writing a Critique Paper: Seven Easy Steps

Were you assigned or asked by your professor to write a critique paper? It’s easy to write one. Just follow the following four steps in writing a critique paper and three steps in presenting it, then you’re ready to go.

One of the students’ requirements I specified in the course module is a critique paper. Just so everyone benefits from the guide I prepared for that class, I share it here.

To standardize the format they use in writing a critique paper, I came up with the following steps to make their submissions worthwhile.

Since they are graduate students, more is expected of them. Hence, most of the verbs I use in writing the lesson’s objectives reside in the domain of higher thinking skills or HOTS. Developing the students’ critical thinking skills will help them analyze future problems and propose solutions that embody environmental principles thus resonate desirable outcomes aligned with the goal of sustainable development.

Table of Contents

Step-by-step procedure in writing a critique paper.

I quickly wrote this simple guide on writing a critique paper to help you evaluate any composition you want to write about. It could be a book, a scientific article, a gray paper, or whatever your professor assigns. I integrated the essence of the approach in this article.

The critique paper essentially comprises two major parts, namely the:

1) Procedure in Writing a Critique Paper, and the

2) Format of the Critique Paper.

First, you will need to know the procedure that will guide you in evaluating a paper. Second, the format of the critique paper refers to how you present it so that it becomes logical and scholarly in tone.

The Four Steps in Writing a Critique Paper

Here are the four steps in writing a critique paper:

To write a good critique paper, it pays to adhere to a smooth flow of thought in your evaluation of the piece. You will need to introduce the topic, analyze, interpret, then conclude it.

Introduce the Discussion Topic

Introduce the topic of the critique paper. To capture the author’s idea, you may apply the 5Ws and 1H approach in writing your technical report.

That means, when you write your critique paper, you should be able to answer the Why , When , Where , What , Who , and How questions. Using this approach prevents missing out on the essential details. If you can write a critique paper that adheres to this approach, that would be excellent.

Here’s a simplified example to illustrate the technique:

The news article by John Doe was a narrative about a bank robbery. Accordingly, a masked man (Who) robbed a bank (What) the other day (When) next to a police station (Where) . He did so in broad daylight (How) . He used a bicycle to escape from the scene of the crime (How) . In his haste, he bumped into a post. His mask fell off; thus, everyone saw his face, allowing witnesses to describe him. As a result, he had difficulty escaping the police, who eventually retrieved his loot and put him in jail because of his wrongdoing (Why) .

Hence, you give details about the topic, in this case, a bank robbery. Briefly describe what you want to tell your audience. State the overall purpose of writing the piece and its intention.

Is the essay written to inform, entertain, educate, raise an issue for debate, and so on? Don’t parrot or repeat what the writer wrote in his paper. And write a paragraph or a few sentences as succinctly as you can.

Analyze means to break down the abstract ideas presented into manageable bits.

What are the main points of the composition? How was it structured? Did the view expressed by the author allow you, as the reader, to understand?

In the example given above, it’s easy to analyze the event as revealed by the chain of events. How do you examine the situation?

The following steps are helpful in the analysis of information:

- Ask yourself what your objective is in writing the critique paper. Come up with a guidepost in examining it. Are you looking at it with some goal or purpose in mind? Say you want to find out how thieves carry out bank robberies. Perhaps you can categorize those robberies as either planned or unplanned.

- Find out the source, or basis, of the information that you need. Will you use the paper as your source of data, or do you have corroborating evidence?

- Remove unnecessary information from your data source. Your decision to do so depends on your objective. If there is irrelevant data, remove it from your critique.

We can use an analogy here to clearly explain the analysis portion.

If you want to split a log, what would you do? Do you use an ax, a chainsaw, or perhaps a knife? The last one is out of the question. It’s inappropriate.

Thus, it would be best if you defined the tools of your analysis. Tools facilitate understanding and allow you to make an incisive analysis.

Read More : 5 Tools in Writing the Analysis Section of the Critique Paper

Now, you are ready to interpret the article, book, or any composition once the requisites of analysis are in place.

Visualize the event in your mind and interpret the behavior of actors in the bank robbery incident. You have several actors in that bank heist: the robber, the police, and the witnesses of the crime.

While reading the story, it might have occurred to you that the robber is inexperienced. We can see some discrepancies in his actions.

Imagine, his mode of escape is a bicycle. What got into him? Maybe he did not plan the robbery at all. Besides, there was no mention that the robber used a gun in the heist.

That fact confirms the first observation that he was not ready at all. Escaping the scene of the crime using a bicycle with nothing to defend himself once pursued? He’s insane. Unimaginable. He’s better off sleeping at home and waiting for food to land on his lap if food will come at all.

If we examine the police’s response, they were relatively quick. Right after the robber escaped the crime scene, they appeared to remedy the situation. The robber did not put up a fight.

What? With bare knuckles? It makes little sense.

If we look at the witnesses’ behavior, we can discern that perhaps they willingly informed the police of the bank robber’s details. They were not afraid. And that’s because the robber appears to be unarmed. But there was no specific mention of it.

Narrate the importance of each of the different sections or paragraphs. How does the write-up contribute to the overall picture of the issue or problem being studied?

Assess or Evaluate

Finally, judge whether the article was a worthwhile account after all. Did it meet expectations? Was it able to convey the information most efficiently? Or are there loopholes or flaws that should have been mentioned?

Format of Presenting the Critique Paper

The logical format in writing a critique paper comprises at least three sections: the introduction, the body, and the conclusion. This approach is systematic and achieves a good flow that readers can follow.

Introduction

Include the title and name of the author in your introduction. Make a general description of the topic being discussed, including the author’s assumptions, inferences, or contentions. Find out the thesis or central argument , which will be the basis of your discussion.

The robbery example appears to be inappropriate to demonstrate this section, as it is so simple. So we level up to a scientific article.

In any scientific article, there is always a thesis that guides the write-up. A thesis is a statement that expresses what the author believes in and tries to test in his study. The investigation or research converges (ideally) to this central theme as the author’s argument.

You can find the thesis in the paper’s hypothesis section. That’s because a hypothesis is a tentative thesis. Hypo means “below or under,” meaning it is the author’s tentative explanation of whatever phenomenon he tackles.

If you need more information about this, please refer to my previous post titled “ How to Write a Thesis .”

How is the introduction of a critique paper structured? It follows the general guidelines of writing from a broad perspective to more specific concerns or details. See how it’s written here: Writing a Thesis Introduction: from General to Specific .

You may include the process you adopted in writing the critique paper in this section.

The body of the paper includes details about the article being examined. It is here where you place all those musings of yours after applying the analytical tools .

This section is similar to the results and discussion portion of a scientific paper. It describes the outcome of your analysis and interpretation.

In explaining or expressing your argument, substantiate it by citing references to make it believable. Make sure that those references are relevant as well as timely. Don’t cite references that are so far out in the past. These, perhaps, would not amount to a better understanding of the topic at hand. Find one that will help you understand the situation.

Besides, who wants to adopt the perspective of an author who has not even got hold of a mobile phone if your paper is about using mobile phones to facilitate learning during the pandemic caused by COVID-19 ? Find a more recent one that will help you understand the situation.

Objectively examine the major points presented by the author by giving details about the work. How does the author present or express the idea or concept? Is he (or she) convincing the way he/she presents his/her paper’s thesis?

Well, I don’t want to be gender-biased, but I find the “he/she” term somewhat queer. I’ll get back to the “he” again, to represent both sexes.

I mention the gender issue because the literature says that there is a difference in how a person sees things based on gender. For example, Ragins & Sundstrom (1989) observed that it would be more difficult for women to obtain power in the organization than men. And there’s a paper on gender and emotions by Shields et al. (2006) , although I wouldn’t know the outcome of that study as it is behind a paywall. My point is just that there is a difference in perspective between men and women. Alright.

Therefore, always find evidence to support your position. Explain why you agree or disagree with the author. Point out the discrepancies or strengths of the paper.

Well, everything has an end. Write a critique paper that incorporates the key takeaways of the document examined. End the critique with an overall interpretation of the article, whatever that is.

Why do you think is the paper relevant in the course’s context that you are taking? How does it contribute to say, the study of human behavior (in reference to the bank robbery)? Are there areas that need to be considered by future researchers, investigators, or scientists? That will be the knowledge gap that the next generation of researchers will have to look into.

If you have read up to this point, then thank you for reading my musings. I hope that helped you clarify the steps in writing a critique paper. A well-written critique paper depends on your writing style.

Read More : How to Write an Article with AI: A Guide to Using AI for Article Creation and Refinement

Notice that my writing style changes based on the topic that I discuss. Hence, if your professor assigns you a serious, rigorous, incisive, and detailed analysis of a scientific article, then that is the way to go. Adopt a formal mode in your writing.

Final Tip : Find a paper that is easy for you to understand. In that way, you can clearly express your thoughts. Write a critique paper that rocks!

Related Reading

Master Content Analysis: An All-in-One Guide

Ragins, B. R., & Sundstrom, E. (1989). Gender and power in organizations: A longitudinal perspective. Psychological bulletin , 105 (1), 51.

Shields, S. A., Garner, D. N., Di Leone, B., & Hadley, A. M. (2006). Gender and emotion. In Handbook of the sociology of emotions (pp. 63-83). Springer, Boston, MA.

© 2020 November 20 P. A. Regoniel

Related Posts

What is the difference between theory testing and theory building, how slow can a heartbeat get.

How to Write a Hypothesis: 5 Important Pointers

About the author, patrick regoniel.

Dr. Regoniel, a faculty member of the graduate school, served as consultant to various environmental research and development projects covering issues and concerns on climate change, coral reef resources and management, economic valuation of environmental and natural resources, mining, and waste management and pollution. He has extensive experience on applied statistics, systems modelling and analysis, an avid practitioner of LaTeX, and a multidisciplinary web developer. He leverages pioneering AI-powered content creation tools to produce unique and comprehensive articles in this website.

Thank you..for your idea ..it was indeed helpful

Glad it helped you Preezy.

This is extremely helpful. Thank you very much!

Thanks for sharing tips on how to write critique papers. This article is very informative and easy to understand.

Welcome. Thank you for your appreciation.

SimplyEducate.Me Privacy Policy

How to Write a Critique Paper: Format, Tips, & Critique Essay Examples

A critique paper is an academic writing genre that summarizes and gives a critical evaluation of a concept or work. Or, to put it simply, it is no more than a summary and a critical analysis of a specific issue. This type of writing aims to evaluate the impact of the given work or concept in its field.

Our specialists will write a custom essay specially for you!

Want to learn more? Continue reading this article written by Custom-writing experts! It contains:

- best tips on how to critique an article or a literary work,

- a critique paper example with introduction, body, and conclusion.

💁 What Is a Critique Paper?

- 👣 Critical Writing Steps

👀 Critical Essay Types

📝 critique paper format, 📑 critique paper outline, 🔗 references.

A critique is a particular academic writing genre that requires you to carefully study, summarize, and critically analyze a study or a concept. In other words, it is nothing more than a critical analysis. That is all you are doing when writing a critical essay: trying to understand the work and present an evaluation. Critical essays can be either positive or negative, as the work deserves.

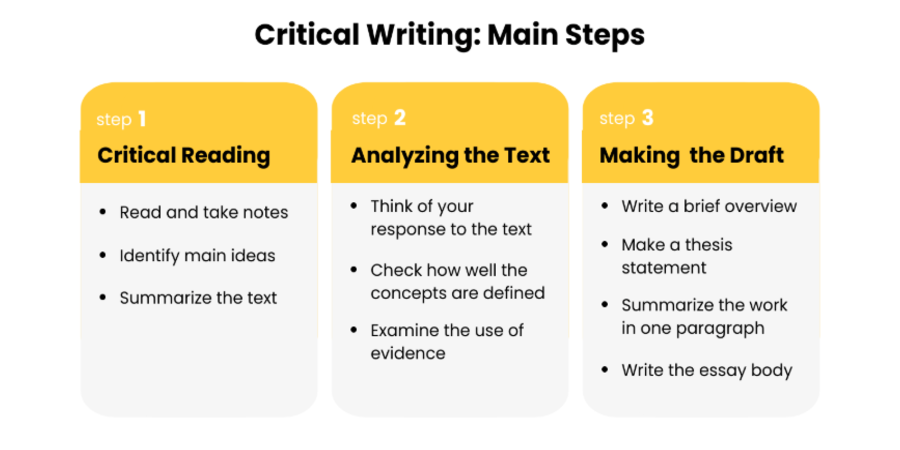

👣 How to Write a Critique Essay: Main Steps

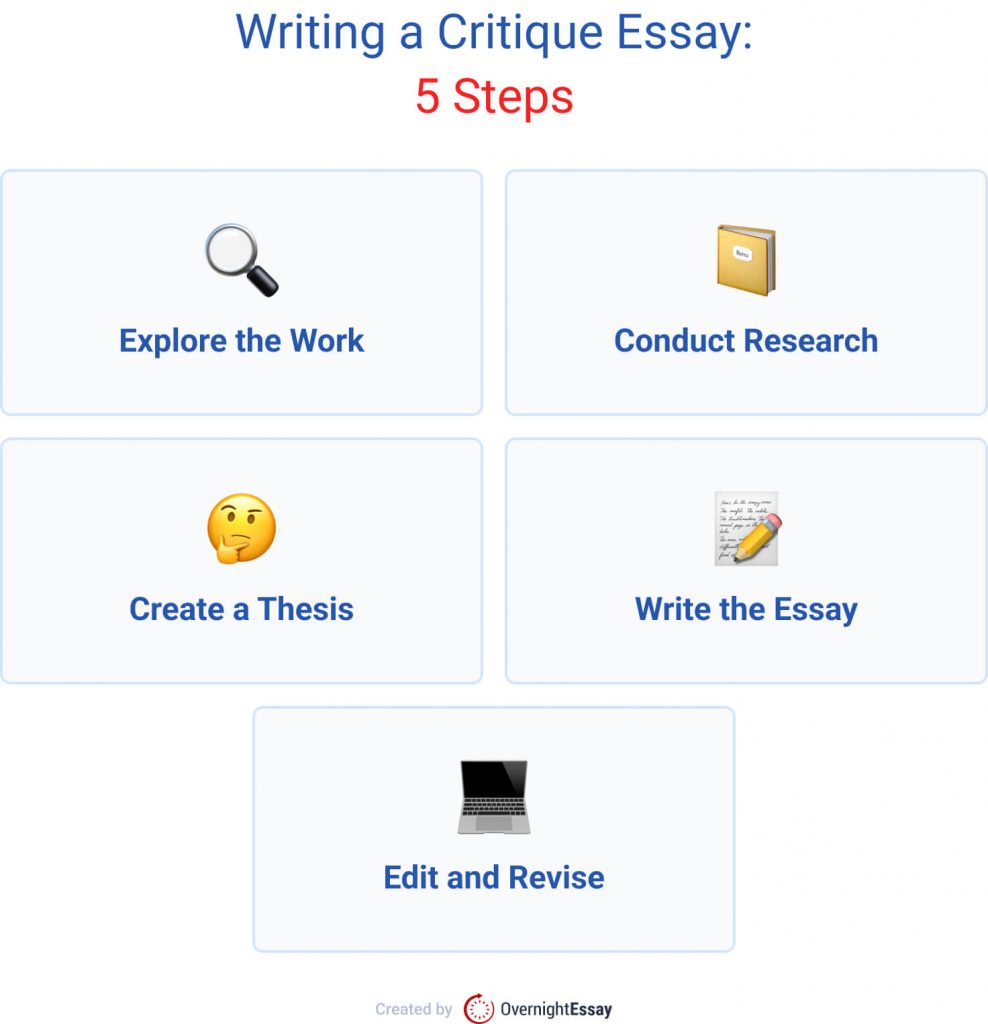

Starting critique essays is the most challenging part. You are supposed to substantiate your opinion with quotes and paraphrases, avoiding retelling the entire text. A critical analysis aims to find out whether an article or another piece of writing is compelling. First, you need to formulate the author’s thesis: what was the literary work supposed to convey? Then, explore the text on how this main idea was elaborated. Finally, draft your critique according to the structure given below.

Step 1: Critical Reading

1.1. Attentively read the literary work. While reading, make notes and underline the essentials.

- Try to come into the author’s world and think why they wrote such a piece.

- Point out which literary devices are successful. Some research in literary theory may be required.

- Find out what you dislike about the text, i.e., controversies, gaps, inconsistency, or incompleteness.

1.2. Find or formulate the author’s thesis.

- What is the principal argument? In an article, it can be found in the first paragraph.

- In a literary work, formulate one of the principal themes, as the thesis is not explicit.

- If you write a critique of painting, find out what feelings, emotions, or ideas, the artist attempted to project.

1.3. Make a summary or synopsis of the analyzed text.

- One paragraph will suffice. You can use it in your critique essay, if necessary.

- The point is to explore the gist.

Step 2: Analyzing the Text

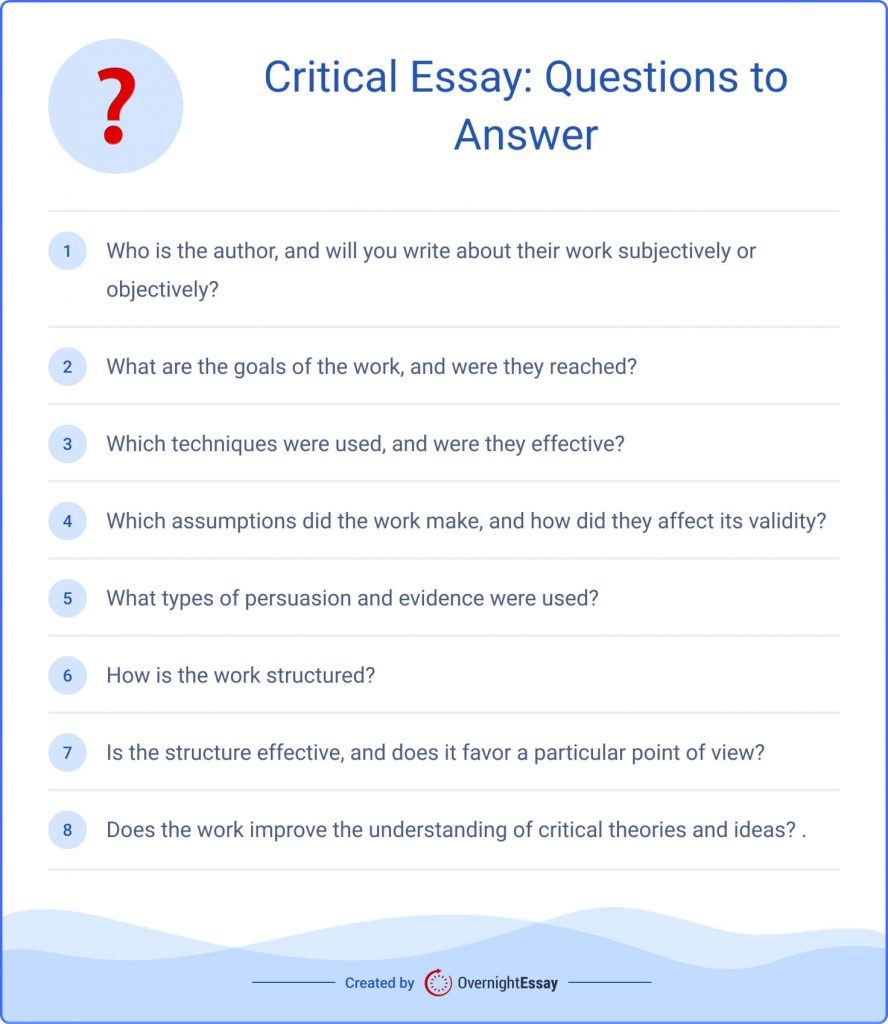

After the reading phase, ask yourself the following questions :

- What was your emotional response to the text? Which techniques, images, or ideas made you feel so?

- Find out the author’s background. Which experiences made them raise such a thesis? What other significant works have they written that demonstrate the general direction of thought of this person?

- Are the concepts used correctly in the text? Are the references reliable, and do they sufficiently substantiate the author’s opinion?

Step 3: Drafting the Essay

Finally, it is time to draft your essay. First of all, you’ll need to write a brief overview of the text you’re analyzing. Then, formulate a thesis statement – one sentence that will contain your opinion of the work under scrutiny. After that, make a one-paragraph summary of the text.

You can use this simple template for the draft version of your analysis. Another thing that can help you at this step is a summary creator to make the creative process more efficient.

Critique Paper Template

- Start with an introductory phrase about the domain of the work in question.

- Tell which work you are going to analyze, its author, and year of publication.

- Specify the principal argument of the work under study.

- In the third sentence, clearly state your thesis.

- Here you can insert the summary you wrote before.

- This is the only place where you can use it. No summary can be written in the main body!

- Use one paragraph for every separate analyzed aspect of the text (style, organization, fairness/bias, etc.).

- Each paragraph should confirm your thesis (e.g., whether the text is effective or ineffective).

- Each paragraph shall start with a topic sentence, followed by evidence, and concluded with a statement referring to the thesis.

- Provide a final judgment on the effectiveness of the piece of writing.

- Summarize your main points and restate the thesis, indicating that everything you said above confirms it.

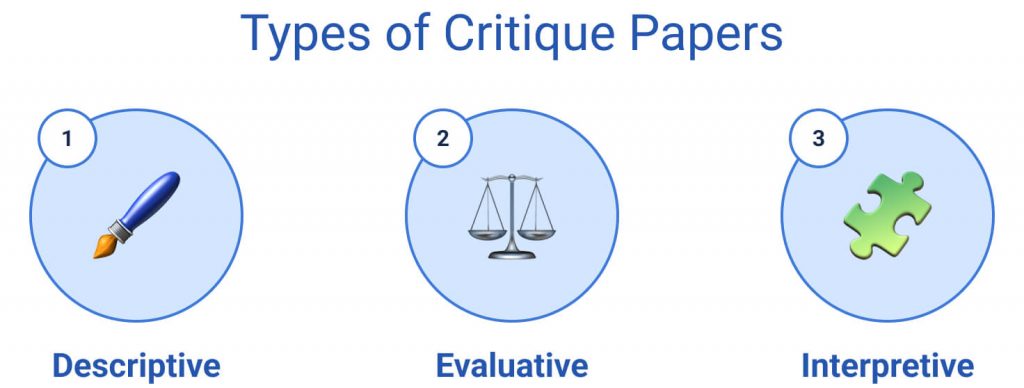

You can evaluate the chosen work or concept in several ways. Pick the one you feel more comfortable with from the following:

Just in 1 hour! We will write you a plagiarism-free paper in hardly more than 1 hour

- Descriptive critical essays examine texts or other works. Their primary focus is usually on certain features of a work, and it is common to compare and contrast the subject of your analysis to a classic example of the genre to which it belongs.

- Evaluative critical essays provide an estimate of the value of the work. Was it as good as you expected based on the recommendations, or do you feel your time would have been better spent on something else?

- Interpretive essays provide your readers with answers that relate to the meaning of the work in question. To do this, you must select a method of determining the meaning, read/watch/observe your analysis subject using this method, and put forth an argument.

There are also different types of critiques. The University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, in the article “ Writing critiques ,” discusses them as well as the appropriate critique language.

Critique Paper Topics

- Critique of the article Is Google Making Us Stupid? by Nicholas Carr .

- Interpret the symbolism of Edgar Alan Poe’s The Black Cat .

- Examine the topicality of the article Impact of Racial/Ethnic Differences on Child Mental Health Care .

- Critical essay on Alice Walker’s short story Everyday Use .

- Discuss the value of the essay The Hanging by George Orwell .

- A critique on the article Stocks Versus Bonds : Explaining the Equity Risk Premium .

- Explore the themes Tennessee Williams reveals in The Glass Menagerie.

- Analyze the relevance of the article Leadership Characteristics and Digital Transformation .

- Critical evaluation of Jonathan Harvey’s play Beautiful Thing .

- Analyze and critique Derek Raymond’s story He Died with His Eyes Open .

- Discuss the techniques author uses to present the problem of choice in The Plague .

- Examine and evaluate the research article Using Evidence-Based Practice to Prevent Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia .

- Explore the scientific value of the article Our Future: A Lancet Commission on Adolescent Health and Wellbeing .

- Describe the ideas E. Hemingway put into his A Clean, Well-Lighted Place .

- Analyze the literary qualities of Always Running La Vida Loca: Gang Days in L. A .

- Critical writing on The Incarnation of Power by Wright Mills.

- Explain the strengths and shortcomings of Tim Kreider’s article The Busy Trap .

- Critical response to Woolf’s novel Mrs. Dalloway .

- Examine the main idea of Richard Godbeer’s book Escaping Salem .

- The strong and weak points of the article The Confusion of Tongues by William G. Bellshaw .

- Critical review of Gulliver’s Travels .

- Analyze the stylistic devices Anthony Lewis uses in Gideon’s Trumpet.

- Examine the techniques Elie Wiesel uses to show relationship transformation in the book Night .

- Critique of the play Fences by August Wilson .

- The role of exposition in Achebe’s novel Things Fall Apart.

- The main themes John Maxwell discusses in his book Disgrace .

- Critical evaluation of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 .

- The ideas and concept of the book The Vegetarian Imperative .

- Different points of view on one historical figure in the book Two Lives of Charlemagne .

Since the APA critique paper format is one of the most common, let’s discuss it in more detail. Check out the information below to learn more:

The APA Manual recommends using the following fonts:

- 11-point Calibri,

- 11-point Arial,

- 10-point Lucida Sans Unicode,

- 12-point Times New Roman,

- 11-point Georgia,

- 10-point Computer Modern.

Receive a plagiarism-free paper tailored to your instructions. Cut 15% off your first order!

Add 1-inch margins on all sides.

📌 Page numbers

Page numbers should appear at the top right-hand corner, starting with the title page.

📌 Line spacing

The entire document, including the title page and reference list, should be double-spaced.

Get an originally-written paper according to your instructions!

📌 Title page

The title page should include the following information:

- page number 1 in the top right-hand corner of the page header,

- paper title,

- the student’s name,

- the name of the department and the college or university,

- course number and name,

- the instructor’s name,

- due date (the date format used in your country).

📌 Critique paper title

The title of your critique paper should be no more than 12 words. In addition, it should be centered and typed in bold using title case.

📌 In-text citations

For the in-text citation, provide the author’s last name and publication year in brackets. If you are using direct citation, add the page number after the year.

📌 References

The last page of your paper should include a list of all sources cited in your essay. Here’s a general format of book and journal article citations you should use:

Book: Last name, First initial. Middle initial. (Year). Book title: Subtitle . Publisher.

Journal article: Last name, First initial. Middle initial. (Year). Title of the article. Journal Title, volume (issue number), start page–end page.

The main parts of good critical response essays are:

- Introduction. The introduction is the most essential part of the critical response. It should be concise and include the author and title of the work being analyzed, its main idea, and a strong thesis statement.

- Summary. This should be brief and to the point. Only the author’s/creator’s main ideas and arguments should be included.

- Analysis/interpretation. Discuss what the author’s/creator’s primary goal was and determine whether this goal was reached successfully. Use the evidence you have gathered to argue whether or not the author/creator achieved was adequately convincing (remember there should be no personal bias in this discussion).

- Evaluation/response. At this point, your readers are ready to learn your objective response to the work. It should be professional yet entertaining to read. Do not hesitate to use strong language. You can say that the work you analyzed was weak and poorly-structured if that is the case, but keep in mind that you have to have evidence to back up your claim.

- Conclusion. The last paragraph of your work should restate the thesis statement, summarize the key points, and create a sense of closure for the readers.

Critique Paper Introduction

The introduction is setting the stage for your analysis. Here are some tips to follow when working on it:

- Provide the reader with a brief synopsis of the main points of the work you are critiquing .

- State your general opinion of the work , using it as your thesis statement. The ideal situation is that you identify and use a controversial thesis.

- Remember that you will uncover a lot of necessary information about the work you are critiquing. You mustn’t make use of all of it, providing the reader with information that is unnecessary in your critique. If you are writing about Shakespeare, you don’t have to waste your or your reader’s time going through all of his works.

Critique Paper Body

The body of the critique contains the supporting paragraphs. This is where you will provide the facts that prove your main idea and support your thesis. Follow the tips below when writing the body of your critique.

- Every paragraph must focus on a precise concept from the paper under your scrutiny , and your job is to include arguments to support or disprove that concept. Concrete evidence is required.

- A critical essay is written in the third-person and ensures the reader is presented with an objective analysis.

- Discuss whether the author was able to achieve their goals and adequately get their point across.

- It is important not to confuse facts and opinions . An opinion is a personal thought and requires confirmation, whereas a fact is supported by reliable data and requires no further proof. Do not back up one idea with another one.

- Remember that your purpose is to provide the reader with an understanding of a particular piece of literature or other work from your perspective. Be as specific as possible.

Critique Paper Conclusion

Finally, you will need to write a conclusion for your critique. The conclusion reasserts your overall general opinion of the ideas presented in the text and ensures there is no doubt in the reader’s mind about what you believe and why. Follow these tips when writing your conclusion:

- Summarize the analysis you provided in the body of the critique.

- Summarize the primary reasons why you made your analysis .

- Where appropriate, provide recommendations on how the work you critiqued can be improved.

For more details on how to write a critique, check out the great critique analysis template provided by Thompson Rivers University.

If you want more information on essay writing in general, look at the Secrets of Essay Writing .

Example of Critique Paper with Introduction, Body, and Conclusion

Check out this critical response example to “The Last Inch” by James Aldridge to show how everything works in practice:

Introduction

In his story “The Last Inch,” James Aldridge addresses the issue of the relationship between parents and children. The author captured the young boy’s coming into maturity coinciding with a challenging trial. He also demonstrated how the twelve-year-old boy obtained his father’s character traits. Aldridge’s prose is both brutal and poetic, expressing his characters’ genuine emotions and the sad truths of their situations.

Body: Summary

The story is about Ben Ensley, an unemployed professional pilot, who decides to capture underwater shots for money. He travels to Shark Bay with his son, Davy. Ben is severely injured after being attacked by a shark while photographing. His last hope of survival is to fly back to the little African hamlet from where they took off.

Body: Analysis

The story effectively uses the themes of survival and fatherhood and has an intriguing and captivating plot. In addition, Ben’s metamorphosis from a failing pilot to a determined survivor is effectively presented. His bond with his son, Davy, adds depth and emotional importance to the story. At the same time, the background information about Ben’s past and his life before the shark attack could be more effectively integrated into the main story rather than being presented as separate blocks of text.

Body: Evaluation

I find “The Last Inch” by James Aldridge a very engaging and emotional story since it highlights the idea of a father’s unconditional love and determination in the face of adversity. I was also impressed by the vivid descriptions and strong character development of the father and son.

Conclusion

“The Last Inch” by James Aldridge is an engaging and emotional narrative that will appeal to readers of all ages. It is a story of strength, dedication, and the unbreakable link between father and son. Though some backstory could be integrated more smoothly, “The Last Inch” impresses with its emotional punch. It leaves the readers touched by the raw power of fatherly love and human will.

📚 Critique Essay Examples

With all of the information and tips provided above, your way will become clearer when you have a solid example of a critique essay.

Below is a critical response to The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman.

When speaking of feminist literature that is prominent and manages to touch on incredibly controversial issues, The Yellow Wallpaper is the first book that comes to mind. Written from a first-person perspective, magnifying the effect of the narrative, the short story by Charlotte Perkins Gilman introduces the reader to the problem of the physical and mental health of the women of the 19th century. However, the message that is intended to concern feminist ideas is rather subtle. Written in the form of several diary entries, the novel offers a mysterious plot, and at the same time, shockingly realistic details.

What really stands out about the novel is the fact that the reader is never really sure how much of the story takes place in reality and how much of it happens in the psychotic mind of the protagonist. In addition, the novel contains a plethora of description that contributes to the strain and enhances the correlation between the atmosphere and the protagonist’s fears: “The color is repellent, almost revolting; a smoldering unclean yellow, strangely faded by the slow-turning sunlight” (Gilman).

Despite Gilman’s obvious intent to make the novel a feminist story with a dash of thriller thrown in, the result is instead a thriller with a dash of feminism, as Allen (2009) explains. However, there is no doubt that the novel is a renowned classic. Offering a perfect portrayal of the 19th-century stereotypes, it is a treasure that is certainly worth the read.

If you need another critique essay example, take a look at our sample on “ The Importance of Being Earnest ” by Oscar Wilde.

And here are some more critique paper examples for you check out:

- A Good Man Is Hard to Find: Critique Paper

- Critique on “The Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman

- “When the Five Rights Go Wrong” Article Critique

- Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey — Comparison & Critique

- “The TrueBlue Study”: Qualitative Article Critique

- Ethical Conflict Associated With Managed Care: Views of Nurse Practitioners’: Article Critique

- Benefits and Disadvantages of Prone Positioning in Severe Acute Respiratory Distress: Article Critique

- Reducing Stress in Student Nurses: Article Critique

- Management of Change and Professional Safety – Article Critique

- “Views of Young People Towards Physical Activity”: Article Critique

Seeing an example of a critique is so helpful. You can find many other examples of a critique paper at the University of Minnesota and John Hopkins University. Plus, you can check out this video for a great explanation of how to write a critique.

- Critical Analysis

- Writing an Article Critique

- The Critique Essay

- Critique Essay

- Writing a Critique

- Writing A Book Critique

- Media Critique

- Tips for an Effective Creative Writing Critique

- How to Write an Article Critique

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to LinkedIn

- Share to email

What is a creative essay, if not the way to express yourself? Crafting such a paper is a task that allows you to communicate your opinion and tell a story. However, even using your imagination to a great extent doesn’t free you from following academic writing rules. Don’t even get...

A compare and contrast essay — what is it? In this type of paper, you compare two different things or ideas, highlighting what is similar between the two, and you also contrast them, highlighting what is different. The two things might be events, people, books, points of view, lifestyles, or...

What is an expository essay? This type of writing aims to inform the reader about the subject clearly, concisely, and objectively. The keyword here is “inform”. You are not trying to persuade your reader to think a certain way or let your own opinions and emotions cloud your work. Just stick to the...

![how to write a critique paper of a story Short Story Analysis: How to Write It Step by Step [New]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/man-sits-end-trolltunga-before-mountains-284x153.jpg)

Have you ever tried to write a story analysis but ended up being completely confused and lost? Well, the task might be challenging if you don’t know the essential rules for literary analysis creation. But don’t get frustrated! We know how to write a short story analysis, and we are...

Have you ever tried to get somebody round to your way of thinking? Then you should know how daunting the task is. Still, if your persuasion is successful, the result is emotionally rewarding. A persuasive essay is a type of writing that uses facts and logic to argument and substantiate...

![how to write a critique paper of a story Common Essay Mistakes—Writing Errors to Avoid [Updated]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/avoid-mistakes-ccw-284x153.jpg)