Japanese Literature

Writing was introduced to Japan from China in the 5th century via the Korean peninsula. The oldest surviving works are two historical records, the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, which were completed in the early 8th century. In the 11th century, during the peak of the Heian Period , the world's first novel, The Tale of Genji , was written in Japan.

During the Meiji Period (1868-1912), an influx of foreign texts spurred the development of modern Japanese literature. Influential authors of the time include Higuchi Ichiyo, whose image is on the 5000 yen bill ; Natsume Soseki , who is best known for his Matsuyama -based novel "Botchan"; and Miyazawa Kenji, a poet and children's literature author from Iwate best known for his work "Night on the Galactic Railroad".

Since then, Japan has maintained a vibrant literary culture, and contemporary writers such as Kawabata Yasunari and Oe Kenzaburo have won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1968 and 1994 respectively.

Below are a few places in Japan where the country's literary heritage can be appreciated:

See also our page about Japanese poetry .

Questions? Ask in our forum .

Links and Resources

The japanese literature home page, introduction to history of japan's literature, literary hot list, national institute of japanese literature.

- Contact Information

- Premodern Timeline

- Modern Timeline

- Modern Fiction - Prewar

- Modern Fiction - Postwar

- Premodern Authors

- Modern Authors

- The Japanese Calendar

- Japanese Era Names

- The Heijō Capital

- The Heian Capital

Literary history

The information contained in the pages on literary history is such as Japanese high school students are expected to know to be able to pass university entrance examinations. Subtlety may be lacking, but the kind of information found here -- together with the rote memorization of certain key passages -- can perhaps be said to constitute the core of the Japanese literary tradition as it is studied by a large proportion of Japan's population.

Premodern period

- The literature of antiquity

- The literature of middle antiquity

- The literature of the middle ages

- The literature of the recent past

Modern period

- Meiji literature

- Taishō literature

- Shōwa, Heisei, and Reiwa literature

Classical literature ( koten bungaku ), meaning literature from the earliest times up to the Meiji Restoration of 1868, is customarily divided by literary scholars into four major periods: jōdai (antiquity) , chūko (middle antiquity) , chūsei (the middle ages) , and kinsei (the recent past) . This method of periodization largely reflects the traditional terminology employed by Japanese historians. Jōdai covers Japanese literary history through the Nara period (710-794); chūko is used more or less synonymously with "literature of the Heian period," from 794 up to the establishment of the Kamakura shogunate in 1192; chūsei takes in the Kamakura (1185-1333), Muromachi (1336-1573), and Azuchi-Momoyama (1573-1600) periods, continuing up to the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1603; and kinsei is most often used to refer to the Edo period (1603-1867). Two caveats are in order. One is that several of these boundaries are "fuzzy": different events are taken by different scholars to mark the end of one period and the beginning of the next (to take one example, the start of the Kamakura period is now taught in schools to be 1185, but 1192 is still firmly established in the popular imagination). The second is that in practice it is quite acceptable to speak of "Heian literature" or "Edo literature," for instance, instead of using the terms given here.

The literature of antiquity (to 794) Written literature in Japan dates from the Nara period, although an oral tradition existed well before that time. The work that is usually taken to reveal the process of change from an oral to a written tradition and from communal to personal concerns is the collection of poems known as the Man'yōshū (The Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves). The literature of middle antiquity (794-1185) Literature in the early Heian period flourished under Chinese (Tang) influence, but became more expressive of native sentiments as Japan withdrew into itself and political institutions based on Chinese models either collapsed or were molded into more congenial forms. Chinese poetry was supplanted by the waka (literally, "Japanese poem") as the preeminent literary form. Imperial collections of poetry were compiled, and prose works, most by women, were written in the newly developed phonetic kana script. The decline of the aristocracy toward the end of the period was paralleled by a loss of creative energy and a growing sense of pessimism, although collections of folktales and popular songs signaled the involvement of a new social class in the production of works of recognized literary value. The literature of the middle ages (1185-1603) The political turbulence associated with the Genpei Wars of 1180 to 1185 and the establishment of the Kamakura bakufu (1192) gave rise to a literature that both centered on military exploits and often expressed disillusion with such exploits. Mujō (impermanence, transience) became a key concept underlying the literature of this period, although at the same time groups devoted to the composition of renga (linked verse) were turning to literature for the purpose of seeking pleasure there. The literature of the recent past (1603-1867) The Edo period was characterized by the growing cultural influence exercised by samurai and townspeople. The commercial class in particular benefited from various economic and technological developments, the result of which was a great flowering of culture in the Genroku period (1688-1704). The haikai master Matsuo Bashō, the novelist Ihara Saikaku, and the dramatist Chikamatsu Monzaemon are all associated with this enormous outburst of creative activity. The nation's cultural center shifted from the Kyoto-Osaka region to Edo in the second half of the eighteenth century, leading to the production of large quantities of gesaku (frivolous works) by the writers who constituted the last literary generation before the advent of Western influence.

The basis for the periodization of modern literature ( kindai bungaku ) is gradually becoming problematic as the "modern" period grows ever longer. The most common division is the one based on the reigns of the emperors who have ruled since 1868: Meiji (1868-1912) , Taishō (1912-1926) , Shōwa (1926-1989) , Heisei (1989-2019) , and Reiwa (from 2019) . The usefulness of these divisions is mitigated, however, both by the basic political continuity of the past 130 years and by the failure to take into account the single most traumatic disruption of that unity, World War II. Literary histories therefore tend to subdivide the modern era by choosing various historical or cultural events to mark the boundaries of important literary developments, perhaps attaching an explanatory note to identify the reason for the division, resulting in a descriptive heading like "The early-to-middle Meiji period (the creation and development of a modern literature)." The situation is further complicated by the recent questioning of "modernization" as a paradigm for constructing Japan's post-Meiji literary history. The effect all this will eventually have on literature as it is taught in the schools is by no means clear at this point. Meiji literature (1868-1912) The Meiji period was when Japan, under Western influence, took the first steps toward developing a modern literature. The major hallmarks up to the time of the Russo-Japanese War are considered to be Tsubouchi Shōyō's theoretical study Shōsetsu shinzui (The Essence of the Novel, 1885) because of its advocacy of psychological realism, and Futabatei Shimei's Ukigumo (Drifting Clouds, 1887), both for its realistic character portrayal and because the narrative medium is an approximation of everyday speech. Counterpoints are offered by the highly stylized prose of the Ken'yūsha (Friends of the Inkstone) group centering on Ozaki Kōyō, and the kind of romanticism evident in the early stories of Mori Ōgai and, especially, the poetry of Kitamura Tōkoku, Shimazaki Tōson, and Yosano Tekkan. The movement known as Japanese Naturalism gained prominence with the publication of Shimazaki Tōson's novel Hakai (The Broken Commandment, 1906) and Tayama Katai's short story Futon (The Quilt, 1907). Naturalism predominated on the literary scene until around 1910, although such authors as Natsume Sōseki, Mori Ōgai, and Nagai Kafū were not associated with it and might even be considered antagonistic to it. The humanistic idealism of the Shirakaba (White Birch) writers from the second decade of the century is taken to mark a turn away from Naturalism and toward a broader definition of literature. Taishō literature (1912-1926) The intellectual aestheticism of Akutagawa Ryūnosuke and decadence of Tanizaki Jun'ichirō characterize this short period, as do (toward its end) the introduction of elements of Western literary modernism in the early work of Yokomitsu Riichi and Kawabata Yasunari, along with the first stirrings of proletarian literature. The Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 is sometimes taken as a major cultural divide in this process. Shōwa (1926-1989), Heisei (1989-2019), and Reiwa (2019- ) literature Proletarian literature was the chief literary movement of the 1920s, supplemented by the uniquely Japanese genre of autobiographical fiction known as the "I novel" ( watakushi shōsetsu or shishōsetsu ). Government suppression of proletarian literature in the 1930s was attended by the publication of "conversion" ( tenkō ) novels by writers compelled to renounce their communist ideals. The subsequent patriotic writings of the war years have largely been forgotten. The end of the war witnessed a resurgent cosmopolitanism that has resulted in a striking literary diversity and has led to a reassessment of the way in which tradition and modernity can be said to contribute to the Japanese sense of identity. This process of reevaluation can be seen in the choice of the two postwar Japanese winners of the Nobel Prize for Literature: Kawabata Yasunari (1968), who titled his acceptance speech "Japan the Beautiful and Myself," and Ōe Kenzaburō (1994), who in deliberate contrast chose the title "Japan the Ambiguous and Myself." The situation since the 1980s has been characterized by an ever increasing diversity, with the "postmodernism" of Murakami Haruki often being one of the last topics mentioned in recent general surveys. This means, in other words, that "accepted" literary history has not really caught up with developments since the late Shōwa period. But any future account of Heisei -- and now Reiwa -- literature will surely have to take note not only of growing categorical fragmentation and diversity but also of the profusion of visually oriented and non-print media (manga, anime, streaming, gaming) that is currently working to reshape the very definition of "literature."

Copyright © Jlit.net. All rights reserved.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

6 What is Japanese literature?

- Published: May 2023

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Like all literatures, Japanese literature is an idiosyncratic idiom that has contributed to a global literary language. For all of the changes over many centuries in historical and literary context, it is possible to discern many threads running through the Japanese tradition that tie the earliest works to the most recent. Perhaps the most enduring strain running through the tradition is the aesthetic and ethical power of the “spirit of words.” There are many histories of Japanese literature than can be written. This history of Japanese literature concludes by returning to its birthright and deepest wellspring, the gift to us of the almost magically unifying, enchanting, and sometimes healing, power of words and their beauty in the face of what it means to be human

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

If you believe AsianInfo has quality, useful information and would like to help - become a Sponsor!

Disclaimer: AsianInfo.org does not guarantee the complete accuracy of the information provided on this site or links. Do your own research and get a professional's opinion before adhering to advice or information contained herein. Use of the information contained herein provided by AsianInfo.org and any mistakes contained within are at the individual risk of the user.

History of Japan's Literature

This page is based on Japan: A Pocket Guide, 1996 Edition ( Foreign Press Center )

Nara Period

Japanese literature traces its beginnings to oral traditions that were first recorded in written form in the early eighth century after a writing system was introduced from China. The Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters) and Nihon shoki (Chronicle of Japan) were completed in 712 and 720 , respectively, as government projects. The former is an anthology of myths, legends, and other stories , while the latter is a chronological record of history . The Fudoki (Records of Wind and Earth), compiled by provincial officials beginning in 713 , describe the history, geography, products, and folklore of the various provinces .

The most brilliant literary product of this period was the Man'yoshu (Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves), an anthology of 4,500 poems composed by people ranging from unknown commoners to emperors and compiled around 759 . Already emerging was a verse form comprising 31 syllables (5-7-5-7-7) known as tanka. In 905 the Kokin wakashu or Kokinshu (Collection of Poems from Ancient and Modern Times) was published as the first poetry anthology commissioned by an emperor; its preface paid high tribute to the vast possibilities of literature .

- Man'yoshu Best 100

- Manyoshu -- Japanese Text Initiative

- Kokin wakashu (260K; binhexed text)

- Kokin wakashu -- Japanese Text Initiative

Heian Period

In the resplendent aristocratic culture that thrived early in the eleventh century, a time when the use of the hiragana alphabet derived from Chinese characters had become widespread, court ladies played the central role in developing literature. One of them, Murasaki Shikibu wrote the 54-chapter novel Genji monogatari (Tale of Genji) [in ealy 11 century, ca 1008 ?] , while another, Sei Shonagon , wrote Makura no soshi (The Pillow Book), a diverse collection of jottings and essays [around 996 ] . Others also wrote diaries and stories, and their psychological portrayals remain fresh and vivid to present-day readers. The appearance of the Konjaku monogatari (Tales of a Time That Is Now Past) around 1120 added a new dimension to literature. This collection of more than 1,000 Buddhist and secular tales from India, China, and Japan is particularly notable for its rich descriptions of the lives of the nobility and common people in Japan at that time.

- Genji Monogatari -- Japanese Text Initiative

- The Tale of Genji Homepage - full text both in Japanese and English

- The Tale of Genji

Kamakura-Muromachi Period

1185 - 1573

In the latter half of the twelfth century warriors of the Taira clan (Heike) seized political power at the imperial court, virtually forming a new aristocracy. Heike mono-gatari (The Tale of the Heike),which depicts the rise and fall of the Taira with the spotlight on their wars with the Minamoto clan (Genji), was completed in the first half of the thirteenth century [before 1219 ] . It is a grand epic deeply rooted in Buddhist ethics and filled with sorrow for those who perished, colorful descriptions of its varied characters, and stirring battle scenes. In former times the tale was narrated to the accompaniment of a Japanese lute. The Shin kokin wakashu (New Collection of Poems from Ancient and Modern Times), an anthology of poetry commissioned by retired Emperor Go-Toba , was also completed around this time [ca 1205 ?] ; it is dedicated to the pursuit of a subtle, profound beauty far removed from the mundane reality of civil strife.

- First book (Spring I) from Shin kokin wakashu (Copyright 1994 by Paul S. Atkins)

- Ogura Hyakunin Isshu - 100 Poems by 100 Poets

This period also produced literature by recluses, typified by Kamo no Chomei 's Hojoki (An Account of My Hut) [ 1212 ] , which reflects on the uncertainty of existence, and Yoshida Kenko 's Tsurezuregusa (Essays in Idleness) [ca 1330 ] , a work marked by penetrating reflections on life. Both works raise the question of spiritual salvation. Meanwhile, the profound thoughts and incisive logic of the Shobogenzo (Treasury of the True Dharma Eye) [before 1237 ] , one of the first Buddhist texts written in Japanese rather than Chinese, marked a major development in Zen thought. The Taiheiki (Chronicle of the Great Peace), depicting the 50 years from 1318 to 1367 when two rival imperial courts struggled for power, is a valuable historical record, while the noh plays perfected by Kan'ami and his son Zeami are of great literary value. Zeami 's Fushi kaden (The Transmission of the Flower of Acting Style) [ 1400 ] is a brilliant essay on dramatic art.

- Japanese traditional art in this homepege for informatino of Noh

1603 - 1868

Around this time the function of literature as a means of social intercourse broadened. Composing renga (successive linked verses by several people forming a long poem) became a favorite pastime, and this gave birth to haikai (a sort of jocular renga) in the sixteenth century. It was the renowned seventeenth century poet Matsuo Basho who perfected a new condensed poetic form of 17 syllables (5-7-5) known as haiku , an embodiment of elegant simplicity and tranquility.

- Dhugal J. Lindsay's Haiku Universe

In the Genroku era (1688-1704) city-dwelling artisans and merchants became the main supporters of literature, and professional artists began to appear. Two giants emerged in the field of prose: Ihara Saikaku, who realistically portrayed the life of Osaka merchants, and Chikamatsu Monzaemon, who wrote joruri , a form of storytelling involving chanted lines, and kabuki plays. These writers brought about a great flowering of literature. Later Yosa Buson composed superb haiku depicting nature, while fiction writer Ueda Akinari produced a collection of gothic stories called Ugetsu monogatari (Tales of Moonlight and Rain) [ 1776 ] .

- See Japanese traditional art in this homepege for informatino of Kabuki

- Kanadehon Chuushingura is a joruri text first performed in 1748 (Japanese)

Meiji Period to present

In the Meiji era ( 1868 - 1912 ) unification of the written and spoken language was advocated, and Futabatei Shimei 's Ukigumo (Drifting Clouds) [ 1887 ] won acclaim as a new form of novel. In poetry circles the influence of translated foreign poems led to a "new style" poetry movement, and the scope of literary forms continued to widen. Novelists Mori Ogai and Natsume Soseki studied in Germany and Britain, respectively, and their works reflect the influence of the literature of those countries. Soseki nurtured many talented literary figures. One of them, Akutagawa Ryunosuke, wrote many superb novelettes based on his detailed knowledge of the Japanese classics. His suicide in 1927 was seen as a symbol of the agony Japan was experiencing in the process of rapid modernization, a major theme of modern Japanese literature.

Naturalism as advocated by Emile Zola dominated Japan's literary world for the first decade of the twentieth century. This school of literature, as represented by Shimazaki Toson, is noted for the "I novel," a style of novel typical of Japan. A number of pre-World War II literary currents, such as proletarian literature and neo-sensualism, petered out during the war but later regained strength, generating a diverse range of works.

In 1968 Kawabata Yasunari became the first Japanese to win the Nobel Prize for literature, and Oe Kenzaburo won it in 1994. They and other contemporary writers, such as Tanizaki Jun'ichiro, Mishima Yukio, Abe Kobo, and Inoue Yasushi, have been translated into other languages. In the last few years works by the remarkably active postwar-generation writers Murakami Ryu (who won the Akutagawa Prize), Murakami Haruki, Yoshimoto Banana, and others have also been translated into many languages and have gained tremendous popularity.

(note: all the Japanese names here follow the Japanese practice of placeing the surname first)

Reference: Research Institute for Publication, Shuppan shihyo nenpo (Annual Publishing Index), 1996.

- AsianStudies.org

- Annual Conference

- EAA Articles

- 2025 Annual Conference March 13-16, 2025

- AAS Community Forum Log In and Participate

Education About Asia: Online Archives

Natsume sōseki and modern japanese literature.

Natsume Sōseki (1867–1916) is one of a handful of individuals who both symbolized Japan’s emergence as a modern nation and helped mold an understanding of the modern condition through his life’s work. Literature was Sōseki’s creative vehicle, but his significance in the context of a broader national identity is greater than the sum of his individual works. In short, his stature is akin to that of Mark Twain, a consensus American icon.

Born at the end of Japan’s final shogunal epoch, the Tokugawa period (1603–1868), Sōseki died several years following the death of the Meiji Emperor. His life span essentially overlaps the seminal Meiji period in Japan’s history (1868–1912), and his literature has long been regarded as having captured the so called Meiji no seishin —the spirit of the Meiji Era. Sōseki’s official status as a Japanese cultural property was acknowledged in the form of his image, which long adorned the nation’s thousand- yen banknote.

Natsume Sōseki’s life and writings were indelibly marked by the intersection of late Tokugawa influences and the ambitious modernization project that marked the Meiji period. The Tokugawa shogunate, based in Edo, had succeeded in maintaining an orderly and regimented society through the imposition of a Confucian-style social hierarchy, with the bushi (samurai) class at the top. Rival samurai clans were effectively marginalized, and the threat of Western colonial incursions was countered through the shogunal sakoku policy of national isolation, which effectively cordoned off the nation from most foreign influences for over two centuries. Tokugawa society was subject to an official moral code that stressed duty and obedience, and its leaders instituted a relatively strict regime of edicts, regulations, and widespread censorship in order to ensure social order.

Thanks to the stable society and a productive domestic economy, Tokugawa cities—especially the shogunal capital of Edo and the mercantile center of Osaka—expanded dramatically, and chōnin (an ascendant merchant class) fostered a stunning variety of arts and entertainment. An urban-based secular culture prevailed, and the pleasure quarters, with their geisha houses, stylish restaurants, and kabuki theaters, attracted anyone with money to burn.

Sōseki’s Japan bore the marks of the nation’s rapid transition to modernity, a major catalyst for which was the arrival of a fleet of American kurofune (“Black Ships”) in 1853, under the command of Matthew Perry. Fifteen years later, the shogunal order gave way to the Meiji Era and the advent of modern Japan. Sōseki was witness to the daunting challenges involved in this radical transformation, and his literature, in the aggregate, is both a reflection of and commentary on the new social, political, and cultural order.

The Meiji mission was to create a modern nation with state-of-the-art education, technology, media, and urban development. Tokyo—the erstwhile Tokugawa shogunal capital—would be a showcase of Japanese modernity and the center of the nation’s cultural and intellectual life. Western know-how would be privileged, together with a new social and political agenda that recognized individualism, autonomy, and equality.

Yet these modern developments had to contend with a significant conservative agenda adopted by the powerful Meiji oligarchs— themselves erstwhile samurai. Cognizant of the need to leverage Tokugawa nativist teachings as a hedge against Western hegemony, they restored the emperor as a national sovereign, patriarch, and Shinto divinity. And they promulgated a “uniqueness myth” centered on kokutai, a term meant to invoke a credo of Japanese uniqueness. Harkening back to Japan’s authoritarian past, the nation’s leaders sought to mold a people attuned to their status as loyal subjects of the emperor. In short, Meiji Japan witnessed the confrontation of a resurgent traditionalism, and the new ethic of individualism and freedom inspired by Western models. This seemingly incongruous design in the fabric of Meiji society would inevitably be reflected in the work of its writers and intellectuals—none more so than Natsume Sōseki.

Sōseki’s Early Years

Natsume Kinnosuke (Sōseki is a pen name) was born in Edo in 1867, one year before the city would be renamed Tokyo with the advent of the Meiji period. The Natsume family had long since lost its samurai status, and Kinnosuke’s father served as a local official of no particular significance. The sixth and last child of older parents who felt the burden of an essentially unwanted child, Kinnosuke was sent out for adoption as an infant to a couple of their acquaintance, the Shiobaras—a not-uncommon practice. The lad would spend some eight years with his adoptive parents, who had serious marital problems of their own, and finally returned to his natal home when he was eight. These early experiences, with their complex emotional freight, would figure in much of his subsequent literature.

The young Kinnosuke was a brilliant student with a flair for literature—the legacy of Japanese and Chinese writings initially, then English literature. As a graduate of Tokyo Imperial University, he took on several rural teaching posts in Shikoku and Kyūshū—experiences that would inspire one of his most popular novels. In 1896, at age twenty-nine, he married Nakane Kyōko, who was ten years younger. She would bear him six children, and they remained together despite temperamental differences and a troubled relationship. Marital problems and mutual barriers to communication would emerge as a key theme of Sōseki’s late novels.

In 1900, Sōseki was sent to England at government expense to study English literature at its source. He spent two years in London, a bitterly trying time notwithstanding his far-ranging literary studies. Two serious impediments would come into play here: a chronic stomach disorder that went untreated and led to a series of hospitalizations and an early death at age forty-nine, and a neurotic disorder diagnosed as shinkei suijaku— neurasthenia—treated by early Japanese specialists in clinical psychology. The neurasthenia symptoms, including seemingly erratic behavior and unusual mood swings, essentially signaled that Sōseki was at risk of a nervous breakdown.

Perhaps a reflection of his melancholic temperament, Sōseki embraced a sardonic, occasionally fatalistic view of modern society and the human condition itself. His keen sensitivity to the problems and pitfalls of social relationships—especially in the context of marriage and family—and the corrosive impact of egocentrism, false pride, and mistrust would deeply color his best-known novels.

Sōseki’s Literary Achievements

As with many of his literary contemporaries, poetry was an early passion and a lifelong pursuit. Sōseki would achieve mastery in both the haiku genre—recalling great predecessors such as Bashō and Buson—and the Chinese poetic genre known as kanshi. Indeed, his stature as a poet would alone have established him as a major literary figure. But together with his great contemporary Mori Ōgai (1862–1922), Sōseki went on to distinguish himself across the spectrum of literary production. Fiction, though, would be his enduring legacy.

Having been appointed to a prestigious professorship in English Literature at the Imperial University in Tokyo, Sōseki found himself more interested in creative writing than what had become an increasingly stultifying academic routine. While still teaching, he achieved critical acclaim for a novel improbably titled I Am a Cat and even more accolades for a second novel, Botchan, whose spirited young protagonist was widely admired. By now committed to a literary career, Sōseki resigned from his university position—all but unthinkable at the time—and embarked on what would be a ten-year career as a professional fiction writer on the staff of the Asahi shimbun, one of the nation’s leading newspapers. He published a series of novels, which initially appeared in daily serialization, over the course of a decade. As such, his work became part of the daily reading diet of millions of Japanese.

Once established in the bundan, the Tokyo-based literary community, Sōseki attracted a number of protégés and disciples, and they would meet regularly on Thursdays at the Natsume home near Waseda University—a gathering known as the Mokuyōkai, the “Thursday Group.” It has since become the stuff of literary legend. Sōseki’s extensive personal writings include many anecdotes and episodes set within his circle of literary colleagues and protégés. 1

Major Works

Sōseki’s novels have earned a privileged place in the Japanese literary canon, and they have enjoyed an “afterlife” in various media forms—film, anime, television drama, and so forth. A brief overview of the major works will reveal the trajectory of a literary career that led to the author being regarded as something akin to Japan’s unofficial “novelist-laureate.” 2

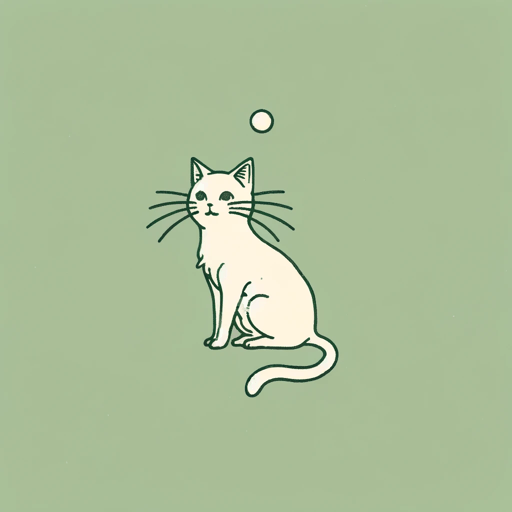

I Am a Cat ( Wagahai wa neko de aru , 1905–1906)

Sōseki’s first novel, a masterpiece of satire inspired in part by British literary forerunners, is set in the household of one “Professor Sneeze” and is narrated by the family’s all-knowing and wryly sardonic cat. The nameless feline harbors a distinctly misanthropic attitude as it lampoons the vanity, pomposity, and general cluelessness of its master.

Insofar as Sneeze’s peccadilloes clearly match those of the author, the work is a self-parody. But it also gives ample voice to Sōseki’s jaundiced view of modern civilization, as well as lampoons the patriotic fervor that was then sweeping the nation as it waged its war with Russia. The novel was a great success, and the author, now intent on pursuing fiction writing in earnest, immediately turned to his next literary project.

Botchan (1906)

The rather naïve young man leaves Tokyo following his parents’ death and takes up a teaching post in the provinces. What ensues is his education in the ways of the world—encounters with crass and duplicitous individuals whose chicanery he cannot endure and whom he resolves to unmask so that justice can be done.

Botchan has long held a privileged place among Japanese readers, largely due to its endearing portrayal of the utterly guileless, principled, and intrepid young protagonist who cannot sit idly by without confronting wrongdoers in positions of authority.

Still a relatively inexperienced writer, Sōseki would move on to experiment with fictional genres and themes. For instance, his next novel, The Three-Cornered World (Kusamakura, 1907), is a seeming retreat into a world of aesthetic self-indulgence abounding in lyrical flights, meditations on beauty, and haiku-esque sensibility. Yet here the author poses a challenge to the then-dominant naturalist coterie, whose agenda of unadorned confessional angst and self-pity he rejected. At the same time, Sōseki points to the value of a cultural traditionalism threatened by the juggernaut of modern civilization.

By this point, Sōseki had finally resigned his professorial post and entered the employ of the Asahi shimbun as a professional novelist. His work, which would henceforth appear in daily serialization, essentially established a literary standard for the nation.

A Trilogy of Novels

Following this early phase of his career, Sōseki can be said to have matured as a writer with the appearance of a trilogy written between 1908 and 1911. The first of these, Sanshirō (1908), concerns an eager but naïve young man from the provinces, Ogawa Sanshirō, and his experiences as a student at Tokyo University. Reminiscent of Botchan’s awakening to the harsh realities of life, Sanshirō, who is initially overwhelmed by the clash and clatter of the big city, gradually learns from his mentors at the university. They in turn serve as a comic send-up of academic pretense and puffery—a target of Sōseki’s first novel. Sadly, Sanshirō’s infatuation with Mineko, the very model of modern, independent Japanese womanhood, will bear no fruit. Notwithstanding his elite university training, the young man has yet to “graduate” into the sort of adult who can function in a competitive and unforgiving world. However, it is precisely his innocent and guileless nature that has helped make Sanshirō, together with Botchan, such perennial favorites among Japanese readers.

Essentially a sequel to Sanshirō, And Then ( Sore kara , 1909) centers on a savvy, somewhat world-weary protagonist, Daisuke, who is in effect a version of Sanshirō as a jaded adult. Daisuke is well-off, smug, and entirely self-absorbed. The novel, eschewing an objective view of Daisuke’s circumstance, instead presents a sustained view of his inner world, and in so doing achieves a remarkable degree of psychological plausibility. Like Sanshirō, Daisuke is romantically attracted to someone unattainable—Michiyo, the wife of his best friend. The novel traces his inner rationalizations and compulsions, and ends with the clever but ineffectual protagonist locked in his private world and on the verge of madness—a victim of the alienating forces of modern society and lacking the means of engaging others or escaping his nightmarish reality.

Sōseki would achieve mastery in both the haiku genre—recalling great predecessors such as Bashō and Buson— and the Chinese poetic genre known as kanshi.

The final novel of Sōseki’s trilogy, The Gate (Mon, 1911), tells of another troubled Tokyoite. Unlike Daisuke, though, Sōsuke has a dead-end job and an unhappy marriage to a woman—Oyone—whom he stole away from a friend. Beset by financial problems and at his wits’ end, Sōsuke looks to religion as a means of escape. Intent upon achieving peace of mind through meditation, he goes to a monastery in Kamakura and immerses himself in Zen practice. But Sōsuke is sadly misguided and finds himself back where he started. His personal dilemma, emblematic of the human condition as understood by the author, is movingly captured in the following passage:

[Sōsuke] looked at the great gate which would never open for him. He was never meant to pass through it. Nor was he meant to be content until he was allowed to do so. He was, then, one of those unfortunate beings who must stand by the gate, unable to move, and patiently wait for the day to end. 3

Some years earlier, Sōseki had himself struggled with Zen meditation before abandoning it in frustration—an experience that left him with a deep cynicism regarding religiosity and ritual practice. His literary alter egos would have no recourse other than to endure their lot or opt for the only escape within their power—suicide. The two novels that mark the culmination of Sōseki’s singular career—Kokoro and Grass on the Wayside — explore the world of characters faced with challenges that eventuate in first one, then the other option. Kokoro in particular has been acclaimed as the great Japanese novel.

Kokoro (1914)

Don’t put too much trust in me. You will learn to regret it if you do . . . I bear with my loneliness now, in order to avoid greater loneliness in the years ahead. You see, loneliness is the price we have to pay for being born in this modern age, so full of freedom, independence, and our own egotistical selves. 4

This cautionary pronouncement only serves to reinforce the bond with the enigmatic Sensei, who has come to assume the status of surrogate father. At long last, Sensei does indeed relate his life story. But it is presented in the form of an extended suicide note, delivered to the friend at the moment when his own father was facing imminent death. He abandons the dying father and his family in the provinces and rushes back to Tokyo. On board the train, he (and the novel’s readers) can finally learn of Sensei’s past.

The document, which comprises half the novel, amounts to a confessional autobiography that tells a tragic tale of self-deception, emotional paralysis, betrayal, and unremitting guilt. Haunted by the consequences of the betrayal, which cost his close friend K his life, and unable to confide in his wife, who had unwittingly played a role in K’s death, Sensei has for years been locked in a prison of his own making. The younger friend thus serves as the catalyst for him to emerge from his cell and tell his story, whereupon he is able to take his own life by way of atonement. The novel ends at the point where the letter ends. As for the fate of the young friend and Sensei’s widow—the novel’s two survivors—Sōseki allows us to draw our own conclusions.

The resonance of Sensei’s suicide with that of General Nogi, the heroic military figure who committed ritual suicide on the day of Emperor Meiji’s state funeral in September 1912, underscores the sense in which this extraordinarily moving novel has been said to capture something at the heart—the kokoro—of Meiji Japan, and by extension, the modern condition itself.

Grass on the Wayside ( Michikusa, 1915)

The novel is channeled principally through the husband, Kenzō—a conceited, cranky intellectual who is prone to melancholy reflections on his past. He is beset by haunting memories of childhood in an adoptive family and has recently been badgered by the adoptive father for a cash settlement in exchange for an annulment of the adoption. Worse yet, he is saddled with a wife who simply cannot understand him. Kenzō does harbor a certain affection for his wife but remains entirely incapable of expressing it. For her part, Osumi is driven to distraction by her blowhard of a husband, wishing that he would let down his guard for once and treat her with some kindness.

Grass on the Wayside concludes with one final sparring match, which concerns the agreed-upon payoff intended to settle things with the adoptive father.

“What a relief,” [Osumi] said. “At least the affair is finally settled . . . ” “But it isn’t, you know.” “What do you mean?” . . . “Hardly anything in life is settled. Things that happen once will go on happening . . . ” He spoke bitterly, almost with venom. His wife gave no answer. She picked up the baby and kissed its red cheeks. “Nice baby, nice baby. We don’t know what daddy is talking about, do we?”

The Sōseki Legacy

Natsume Sōseki’s fiction can be said to mark the coming-of-age of modern Japanese literature, from its origins in the early 1880s. The author achieved a mastery of the modern psychological novel, through which he succeeded in capturing the ebb and flow of moods, conflicted emotions, and confusion that marked his own life and that of his literary alter egos. With remarkable sensitivity and subtlety, Sōseki’s literature explores the travails of individualism in the modern age. Insulated from others by circumstance and personal inclination, his characters ponder the meaning of their lives, wondering who they are and how they got to be that way. They mull over the past and sift through the traces and fragments of memory for something that might yield an answer. And they struggle—often in vain—to make sense of relationships freighted with pain, regret, and a numbing banality.

But there is more to the story—namely, a Sōseki legend that has survived his passing, one that plays upon an essential wisdom attributed to the man and his work. At its core is an epigram with which the author is closely associated— sokuten kyoshi , “Be in accord with heaven and reject the self.” Like many such legends, the exact source is unclear, as is the sense in which Sōseki may have meant for it to be understood. Yet generations of disciples and admirers have maintained that the man embodied a higher wisdom. It is either ironic or entirely fitting that an individual so sensitive to the corrosive forces at work in modern society, and so skeptical about the future, should emerge as a sage.

I would like to think that Sōseki’s bemused expression on the iconic photograph represents his response to this curious state of affairs.

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

NATSUME SŌSEKI’S MAJOR NOVELS

I Am a Cat . Translated by Aiko Itō and Graeme Wilson. Rutland, Vermont; Tokyo, Japan: Charles E. Tuttle Company., 1986.

Botchan. Translated by Joel Cohn. Tokyo: Kodansha International, 2007.

The Three-Cornered World . Translated by Alan Turney. London: Peter Owen, 1965.

Sanshirō. Translated by Jay Rubin. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1977.

And Then . Translated by Norma Moore Field. Baton Rouge: Lousiana State University Press, 1978.

The Gate. Translated by Francis Mathy. London: Peter Owen, 1972.

Kokoro. Translated by Edwin McClellan. Chicago: Henry Regnery, 1957.

Grass on the Wayside. Translated by Edwin McClellan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1969.

1. For a study of this body of writing, see my Reflections in a Glass Door: Memory and Melancholy in the Personal Writings of Natsume Sōseki (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2010).

2. See the appended listing of the novels and their respective English translations.

3. Cited in Jay Rubin, “Sōseki,” Modern Japanese Writers , ed. Jay Rubin (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2001), 372. The passage was translated by Edwin McClellan. Rubin’s essay (349–384) provides a detailed and astute commentary on the author’s work. Here I would like to acknowledge Jay Rubin’s important contributions as a Sōseki scholar and translator.

4. Edwin McClellan, trans., Kokoro (Chicago: Henry Regnery, 1957), 30.

5. A final novel, Light and Darkness (Meian), was left incomplete at the time of Sōseki’s death on December 9, 1916.

6. Based upon Edwin McClellan, trans., Grass on the Wayside (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1969), 168–169.

- Latest News

- Join or Renew

- Education About Asia

- Education About Asia Articles

- Asia Shorts Book Series

- Asia Past & Present

- Key Issues in Asian Studies

- Journal of Asian Studies

- The Bibliography of Asian Studies

- AAS-Gale Fellowship

- Council Grants

- Book Prizes

- Graduate Student Paper Prizes

- Distinguished Contributions to Asian Studies Award

- First Book Subvention Program

- External Grants & Fellowships

- AAS Career Center

- Asian Studies Programs & Centers

- Study Abroad Programs

- Language Database

- Conferences & Events

- #AsiaNow Blog

Throughout May, AAS is celebrating Asian American and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander Heritage Month. Read more

Japanese Literature

In this collection, discover insightful analyses of iconic Japanese literary texts, including The Tale of Genji, which is widely considered the world’s earliest surviving novel. Learn how the different authors portray a diverse set of topics, from interpersonal relationships and identity, to dystopias and the experience of Japanese internment camps during World War II.

by Haruki Murakami

1Q84 is a novel written by the Japanese author Haruki Murakami. The book was first published in Japanese in three volumes and released in 2009 and 2010, ahead of an English translation published in 2011. Set in 1984 in Tokyo, the story concerns an assassin who stumbles upon an alternate world she refers to as 1Q84. There, she becomes embroiled in a conspiracy involving an abusive religious cult.This study guide refers to the 2011 edition ... Read 1Q84 Summary

A Different Mirror

By ronald takaki.

A Different Mirror: A History of Multicultural America by Ronald Takaki is a revisionist account of American history that provides an in-depth view of America as a country populated and built by diverse peoples of the world. Originally published in 1993 by Little, Brown and Company, this study guide uses the updated 2008 edition. In 1994 A Different Mirror received an Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for its contributions to advancing understandings of racism and human diversity.Takaki’s ... Read A Different Mirror Summary

A Family Supper

By kazuo ishiguro.

Kazuo Ishiguro is an English and Japanese author who is most well-known for prizewinning novels such as The Remains of the Day (1989) and Never Let Me Go (2005), the latter of which was adapted into a film in 2010. “A Family Supper” is a 1983 short story that was originally published in a volume of Ishiguro’s works, titled Firebird 2: Writing Today. The short story begins when an unnamed narrator returns to his homeland ... Read A Family Supper Summary

After Dark was published in 2004 by acclaimed Japanese author Haruki Murakami. The novel follows protagonist Mari Asai through one night in Tokyo. Mari has run-ins with organized crime, people on the run, and others who do not fit into Tokyo’s often conservative society. After Dark was met with lackluster critical reception, partially due to Murakami’s characteristic ambiguity and apparent lack of an ending; however, others argue that this ambiguity allows readers to interpret events ... Read After Dark Summary

All I Asking for Is My Body

By milton murayama.

All I Asking for Is My Body (1975) was written by Milton Murayama and is a fictionalized autobiography based on Murayama’s upbringing on a Hawaiian sugar cane plantation in the 1930s. Kiyoshi Oyama, the American son of Japanese immigrants, narrates the story using a mixture of Standard English with Hawaiian English Creole. The novel explores themes of Japanese filial responsibilities as opposed to American individualism and the treatment of Japanese Americans at the start of ... Read All I Asking for Is My Body Summary

A Pale View of Hills

A Pale View of Hills (1982) is Kazuo Ishiguro’s first novel. Born in Nagasaki in 1954, Ishiguro immigrated with his family to the United Kingdom when he was five years old. Despite his family’s Japanese origins, the author frequently states in interviews that his experience with Japanese culture is very limited, as he spent all his adult life in England. Simultaneously, however, growing up in a Japanese family developed in Ishiguro a different perspective compared ... Read A Pale View of Hills Summary

A Wild Sheep Chase

A Wild Sheep Chase is the third novel by Haruki Murakami, an internationally-acclaimed author who most recently won the Jerusalem Prize, and whose work has been translated into over fifty languages. It was originally published in 1982. The 29-year-old narrator of the novel, who is never named, works for an advertising agency in Tokyo and leads a lonely and regimented life. He is divorced, childless, and has a girlfriend who moonlights as a prostitute, proofreader ... Read A Wild Sheep Chase Summary

Before the Coffee Gets Cold

By toshikazu kawaguchi, transl. geoffrey trousselot.

... Read Before the Coffee Gets Cold Summary

by Masuji Ibuse

Black Rain is a 1965 historical novel by Japanese author Masuji Ibuse. The novel blends authentic accounts and information with a fictional plot to describe the aftermath of the destruction of the Japanese city of Hiroshima by an American atomic bomb in 1945. Black Rain was adapted into a film in 1989. This guide uses an eBook version of the 1979 edition of Black Rain, translated into English by John Bester.Plot SummaryShigematsu Shizuma is a ... Read Black Rain Summary

Breasts and Eggs

By mieko kawakami, transl. sam bett, transl. david boyd.

... Read Breasts and Eggs Summary

Citizen 13660

By miné okubo.

Miné Okubo’s Citizen 13660 is a graphic memoir about the Japanese American author’s experience in Japanese internment camps during World War II. First published in 1946, Citizen 13660 is told from Okubo’s first-person narrator experience, although the author draws herself in third-person in nearly every scene.Plot OverviewAfter Okubo’s mother’s passing, she lived with her brother in Berkeley, California until the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor in 1941. In response, US President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive ... Read Citizen 13660 Summary

Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage

Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage is a 2014 novel by renowned Japanese novelist Haruki Murakami. The novel tells the story of a man who attempts to overcome past emotional suffering to make his present life more rewarding. Through Tsukuru’s point of view, we see the ripple effects of rejection and the necessity of sometimes confronting the past to make sense of who we are in the present. After a group of friends ... Read Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage Summary

Confessions

By kanae minato, transl. stephen snyder.

... Read Confessions Summary

Confessions of a Mask

By yukio mishima.

Confessions of a Mask is a novel by Yukio Mishima, first published in Japan in 1949. The novel takes place during and immediately after World War II and centers on the struggles of a young man named Kochan. It has significant elements of the coming-of-age (bildungsroman) and queer literature genres, as Kochan is a closeted gay man trying to navigate his complex inner life and sexuality in contrast with his carefully controlled outer persona. The ... Read Confessions of a Mask Summary

Convenience Store Woman

By sayaka murata, transl. ginny tapley takemori.

... Read Convenience Store Woman Summary

Desert Exile

By yoshiko uchida.

Desert Exile tells the story of the author Yoshiko Uchida and the Uchida family’s experience as Japanese-Americans interned in concentration camps by the U.S. government after the Pearl Harbor attacks during World War II. The book follows a linear narrative arc that details the Uchidas’ experience, while Uchida often reflects discursively, using one point in her life as a vortex for connecting that moment to another memory and in turn creating a larger impression of ... Read Desert Exile Summary